This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Христо Зарев Игнатов (talk | contribs) at 18:25, 26 June 2015 (Removed unhappy removal). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 18:25, 26 June 2015 by Христо Зарев Игнатов (talk | contribs) (Removed unhappy removal)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) This article is about the 9th-century Khanas of Bulgaria. For other uses, see Krum (disambiguation). Khanas of Bulgaria| Krum the Fearsome | |

|---|---|

| Khanas of Bulgaria | |

A 14th century depiction of Krum. A 14th century depiction of Krum. | |

| Reign | 803–814 |

| Predecessor | Kardam |

| Successor | Omurtag |

| Died | (814-04-13)13 April 814 |

| Spouse | Unknown |

| Issue | Omurtag Budim |

| House | "Krum's dynasty" (possibly Dulo) |

Krum the Fearsome (Template:Lang-bg, Template:Lang-el) was khanas of Bulgaria during the First Bulgarian Empire from sometime after 796 but before 803 until his death in 814. During his reign the Bulgarian territory doubled in size, spreading from the middle Danube to the Dnieper and from Odrin to the Tatra Mountains. According to the Encyclopaedia Britannica his able and energetic rule brought law and order to Bulgaria and developed the rudiments of state organisation.

"(ruler) from God", from the Indo-European *su- and baga-, i.e. *su-baga (an equivallent of the Greek phrase ὁ ἐκ Θεοῦ ἄρχων, ho ek Theou archon, which is common in Bulgar inscriptions). This titulature presumably persisted until the Bulgars adopted Christianity.<ref>Sedlar, Jean W,. [http://books.google.com/books?

Establishment of new borders

Around 805, Krum defeated the Avar Khaganate to destroy the remainder of the Avars and to restore Bulgar authority in Ongal again, the traditional Bulgar name for the area north of the Danube across the Carpathians covering Transylvania and along the Danube into eastern Pannonia. This resulted in the establishment of a common border between the Frankish Empire and Bulgaria, which would have important repercussions for the policy of Krum's successors.

Conflict with Nikephoros I

Krum engaged in a policy of territorial expansion. In 807 Bulgarian forces defeated the Byzantine army in the Struma valley. In 809 Krum besieged and forced the surrender of Serdica (Sofia). This victory provoked Byzantine Emperor Nikephoros I to settle Anatolian populations along the frontier to protect it and to attempt to retake and refortify Serdica, although this enterprise failed.

In early 811, Nikephoros I undertook a massive expedition against Bulgaria, advancing to Marcellae (near Karnobat). Here Krum attempted to negotiate on July 11, 811, but Nikephoros was determined to continue with his plunder. His army somehow avoided Bulgarian ambushes in the Balkan Mountains and made its way into Moesia. They managed to take over Pliska on July 20, as only a small, hastily assembled army was in their way. Here Nikephoros helped himself to the treasures of the Bulgarians while setting the city afire and turning his army on the population. A new diplomatic tentative from Krum was rebuffed, and Nikephoros once again showed himself to be a brutal, savage, and merciless leader.

The Chronicle of 12th-century patriarch of the Syrian Jacobites, Michael the Syrian, describes the brutalities and atrocities of Nikephoros: "Nikephoros, emperor of the Byzantine empire, walked into the Bulgarians' land: he was victorious and killed great number of them. He reached their capital, seized it and devastated it. His savagery went to the point that he ordered to bring their small children, got them tied down on earth and made thresh grain stones to smash them."

While Nikephoros I and his army pillaged and plundered the Bulgarian capital, Krum mobilized as many soldiers as possible, giving weapons even to peasants and women. This army was assembled in the mountain passes to intercept the Byzantines as they returned to Constantinople. At dawn on July 26, the Bulgarians managed to trap the retreating Nikephoros in the Vărbica pass. The Byzantine army was wiped out in the ensuing battle and Nikephoros was killed, while his son Staurakios was carried to safety by the imperial bodyguard after receiving a paralyzing wound to the neck. It is said that Krum had the Emperor's skull lined with silver and used it as a drinking cup. This strategic victory secured Krum the respect of the ancient world.

Conflict with Michael I Rangabe

Staurakios was forced to abdicate after a brief reign (he died from his wound in 812), and he was succeeded by his brother-in-law Michael I Rangabe. In 812 Krum invaded Byzantine Thrace, taking Develt and scaring the population of nearby fortresses to flee towards Constantinople. From this position of strength, Krum offered a return to the peace treaty of 716. Unwilling to compromise his regime by weakness, the new Emperor Michael I refused to accept the proposal, ostensibly opposing the clause for exchange of deserters. To apply more pressure on the Emperor, Krum besieged and captured Mesembria (Nesebar) in the autumn of 812.

In February 813 the Bulgarians raided Thrace but were repelled by the Emperor's forces. Encouraged by this success, Michael I summoned troops from the entire Byzantine Empire and headed north, hoping for a decisive victory. Krum led his army south towards Adrianople and pitched camp near Versinikia. Michael I lined up his army against the Bulgarians, but neither side initiated an attack for two weeks. Finally, on June 22, 813, the Byzantines attacked but were immediately turned to flight. With Krum's cavalry in pursuit, the rout of Michael I was complete, and Krum advanced on Constantinople, which he besieged by land. Discredited, Michael was forced to abdicate and become a monk — the third Byzantine Emperor undone by Krum in as many years.

Conflict with Leo V the Armenian

The new emperor, Leo V the Armenian, offered to negotiate and arranged for a meeting with Krum. As Krum arrived, he was ambushed by Byzantine archers and was wounded as he made his escape. Furious, Krum ravaged the environs of Constantinople and headed home, capturing Adrianople en route, transplanting its inhabitants (including the parents of the future Emperor Basil I) across the Danube. In spite of the approach of winter, Krum took advantage of good weather to send a force of 30,000 into Thrace, capturing Arkadioupolis (Lüleburgaz) and carrying off 50,000 captives in the Bulgarian lands across the Danube. The loot from Thrace was used to enrich Krum and his nobility and included architectural elements utilized in the reconstruction of Pliska, perhaps largely by captured Byzantine artisans.

Krum spent the winter preparing for a major attack on Constantinople, where rumor reported the assemblage of an extensive siege park to be transported on 5,000 carts. He died before he set out, however, on April 13, 814, and he was succeeded by his son Omurtag.

Legacy

Krum was remembered for instituting the first known written Bulgarian law code, which ensured subsidies to beggars and state protection to all poor Bulgarians. Drinking, slander, and robbery were severely punished. Through his laws he became known as a strict but just ruler, bringing Slavs and Bulgars into a centralized state.

-

Bulgaria (in yellow) and Europe during the reign of Khanas Krum

Bulgaria (in yellow) and Europe during the reign of Khanas Krum

- Bulgaria under Khanas Krum (new territories gained under his rule are in yellow) Bulgaria under Khanas Krum (new territories gained under his rule are in yellow)

-

Battle at Vărbitsa Pass

Battle at Vărbitsa Pass

-

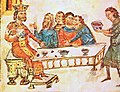

Krum feasts with his nobles as a servant (right) brings the skull of Nikephoros I, fashioned into a drinking cup, full of wine.

Krum feasts with his nobles as a servant (right) brings the skull of Nikephoros I, fashioned into a drinking cup, full of wine.

-

The battle at Versinikia

The battle at Versinikia

See also

Sources and references

- Andreev, Jordan (1999). Кой кой е в средновековна България (Who is Who in Medieval Bulgaria) (in Bulgarian). Sofia.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|chapterurl=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Fine Jr., John V. A. (1983). The Early Medieval Balkans. Ann Arbor.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|chapterurl=(help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

- Gibbon, Edward (1788–89). "Chapter LV, The Bulgarians, the Hungarians and the Russians". The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Vol. V. London: Strahan & Cadell.

- (primary source) Iman, Bahši (1997). Džagfar Tarihy (vol. III). Orenburg.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|chapterurl=(help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - (primary source) Syrien, patriarch of the Syrians Jacobites, Michel le (1905). "t. III". In J.–B. Chabot (ed.). Chronique de Michel le Syrien (in French). Paris: J.–B. Chabot. p. 17.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|chapterurl=(help) - Theophanes the Confessor, Chronicle, Ed. Carl de Boor, Leipzig.

- Васил Н. Златарски, История на българската държава през средните векове, Част I, II изд., Наука и изкуство, София 1970, pp. 321–376.

- Norwich, John J. (1991). Byzantium: The Apogee. Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. ISBN 0-394-53779-3.

References

- Essential History of Bulgaria in Seven Pages, p. 3, Lyubomir Ivanov, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, Sofia, 2007

- Krum, Encyclopaedia Britannica Online

- Blackwell Synergy - Early Medieval Europe, vol. 10, issue 1, pp. 1-19, March 2001 (Article Abstract)

External links

- Borders of Bulgaria during the reign of Khanas Krum

- History, Rulers of Bulgaria — Khanas Krum

- SCRIPTOR INCERTUS — About the Emperor Nikephoros and how he left his bones in Bulgaria

- Khanas Krum Featured on Bulgarian Commemorative Coin

- Nikolov, A. Khanas Krum in the Byzantine tradition: terrible rumours, misinformation and political propaganda. – In: Studies in honour of Professor Vassil Gjuzelev (= Bulgaria Mediaevalis, 2). Sofia, 2011, 39-47

| Preceded byKardam | Khanas of Bulgaria 803–814 |

Succeeded byOmurtag |

| Bulgarian monarchs | |

|---|---|

| First Empire (680–1018) | |

| Rebels against the Byzantines | |

| Second Empire (1185–1422) |

|

| Rebels against the Ottomans | |

| Principality (1878–1908) and Kingdom (1908–1946) | |