This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Asterixf2 (talk | contribs) at 16:01, 22 October 2016 (→Theological foundations and major themes: note). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 16:01, 22 October 2016 by Asterixf2 (talk | contribs) (→Theological foundations and major themes: note)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| The neutrality of this article's introduction is disputed. Relevant discussion may be found on the talk page. Please do not remove this message until conditions to do so are met. (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| Malleus Maleficarum | |

|---|---|

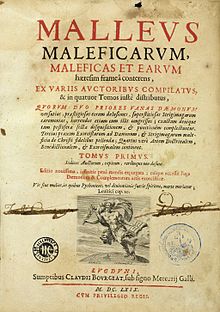

Title page of the seventh Cologne edition of the Malleus Maleficarum, 1520 (from the University of Sydney Library). The Latin title is "MALLEUS MALEFICARUM, Maleficas, & earum hæresim, ut phramea potentissima conterens." (Generally translated into English as The Hammer of Witches which destroyeth Witches and their heresy as with a two-edged sword). Title page of the seventh Cologne edition of the Malleus Maleficarum, 1520 (from the University of Sydney Library). The Latin title is "MALLEUS MALEFICARUM, Maleficas, & earum hæresim, ut phramea potentissima conterens." (Generally translated into English as The Hammer of Witches which destroyeth Witches and their heresy as with a two-edged sword). | |

| Author(s) | Heinrich Kramer and, credited but under modern academic dispute, Jacob Sprenger |

| Date | 1486 |

| Date of issue | 1487 |

The Malleus Maleficarum (commonly rendered into English as "Hammer of Witches"; Der Hexenhammer in German) is a treatise on the prosecution of witches, written in 1486 by Heinrich Kramer, a German Catholic clergyman. The book was first published in Speyer, Germany, in 1487. Jacob Sprenger's name was added as an author beginning in 1519, 33 years after the book's first publication and likewise decades after Sprenger's death; but the veracity of this late addition has been questioned by many historians partly due to the suspicious circumstances of adding him long after his own death partly because a close friend of Sprenger said that the posthumous attribution was false, and partly because Sprenger's known views were in many cases the opposite of the views in the Malleus and Sprenger was likewise a bitter and public opponent of Kramer. In 1490, three years after its publication, the clergy at the University of Cologne condemned the book, although Kramer would falsely claim that several of them had approved it, which they denied. It was later used by royal courts during the Renaissance, and contributed to the increasingly brutal prosecution of witchcraft during the 16th and 17th centuries.

Kramer wrote the Malleus following his expulsion from Innsbruck by the local bishop, due to charges of illegal behavior against Kramer himself, and because of Kramer's obsession with the sexual habits of one of the accused, Helena Scheuberin, which led the other tribunal members to suspend the trial.

Background

See also: Summis desiderantes affectibusMagic, sorcery, and witchcraft had long been condemned by the Church, whose attitude towards witchcraft was explained in the canon Episcopi written in about 900 AD. It stated that witchcraft and magic did not really exist, and that those who believed in such things "had been seduced by the Devil in dreams and visions into old pagan errors". Until about 1400 it was rare for anyone to be accused of witchcraft, but heresies had become a major problem within the Church by the 13th century, and by the 15th century belief in witches was widely accepted in European society. Those convicted of witchcraft typically suffered penalties no more harsh than public penances such as a day in the stocks, but their persecution became more brutal following the publication of the Malleus Maleficarum, as witchcraft became increasingly accepted as a real and dangerous phenomenon.

In 1484 Heinrich Kramer had made one of the first attempts at prosecuting alleged witches in the Tyrol region. It was not a success: he was expelled from the city of Innsbruck. Kramer was opposed by the local clergy partly because of his eccentric behavior (as the Bishop of Innsbruck's verdict indicates), and because he didn't hold any official position as an Inquisitor at the time despite his efforts to make himself into one. According to Diarmaid MacCulloch, writing the book was Kramer's act of self-justification and revenge. Ankarloo and Clark claim that Kramer's purpose in writing the book was to explain his own views on witchcraft, systematically refute arguments claiming that witchcraft does not exist, discredit those who expressed skepticism about its reality, claim that those who practised witchcraft were more often women than men, and to convince magistrates to use Kramer's recommended procedures for finding and convicting witches.

Some scholars have suggested that following the failed efforts in Tyrol, Kramer and Jacob Sprenger (also known as Jacob or Jakob Sprenger) requested explicit authority from Pope to prosecute witchcraft. Kramer received a papal bull Summis desiderantes affectibus in 1484. It allegedly gave full papal approval for the Inquisition to prosecute what was deemed to be witchcraft in general and also gave individual authorizations to Kramer and Sprenger specifically. Within two years after the issuance of the papal bull, Malleus Maleficarum – the most popular manual on witchcraft and its prosecution – was finished and the papal bull was included as part of its preface (1486). There were 13 editions of the manual until 1520 and during later years 1574-1669 it was published 16 times in catholic and protestant countries.

Publication

First edition of the Malleus Maleficarum was published by Kramer (Latinised as "Institoris") and Sprenger in 1487. Scholars have debated how much Sprenger contributed to the work. Some say his role was minor, and that the book was written almost entirely by Kramer, who used the name of Sprenger for its prestige only, while others say there is little evidence for this claim.

The preface also includes an unanimous approbation from the University of Cologne's Faculty of Theology. The authenticity of the Cologne endorsement was first questioned by Joseph Hansen but has not been universally questioned; Christopher S. Mackay rejects Hansen's theory as a misunderstanding. Nevertheless, it is well established by sources outside the "Malleus" that the university's theology faculty condemned the book for unethical procedures and for contradicting Catholic theology on a number of important points. Any apparent approval from the Cologne theologians was an advertising scam by Kramer, The Malleus Maleficarum drew on earlier sources such as Johannes Nider's treatise Formicarius, written 1435/37.

The book became the handbook for secular courts throughout Renaissance Europe, but was not used by the Inquisition, which "denied any authority to the Malleus" in the words of historian Wolfgang Behringer. Between 1487 and 1520 the work was published thirteen times. It was again published between 1574 and 1669 a total of sixteen times. Regardless of the authenticity of the endorsements appearing at the beginning of the book, their presence contributed to the popularity of the work.

Summary of contents

The Malleus Maleficarum asserts that three elements are necessary for witchcraft: the evil intentions of the witch, the help of the Devil, and the Permission of God. The treatise is divided into three sections. The first section is aimed at clergy and tries to refute critics who deny the reality of witchcraft, thereby hindering its prosecution. The second lays the foundation for the next section by describing the actual forms of witchcraft and its remedies. The third section is to assist judges confronting and combating witchcraft, and to aid the inquisitors by removing the burden from them. However, each of these three sections has the prevailing themes of what is witchcraft and who is a witch. The Malleus Maleficarum relies heavily upon earlier works such as Visconti and, most famously, Johannes Nider's Formicarius (1435). It also draws heavily from the works of Augustine and Aquinas.

Section I

Section I examines the concept of witchcraft theoretically, from the point of view of natural philosophy and theology. Specifically it addresses the question of whether witchcraft is a real phenomenon or imaginary, perhaps "deluding phantasms of the devil, or simply the fantasies of overwrought human minds". The conclusion drawn is that witchcraft must be real because the Devil is real. Witches entered into a pact with Satan to allow them the power to perform harmful magical acts, thus establishing an essential link between witches and the Devil.

Section II

Matters of practice and actual cases are discussed, and the powers of witches and their recruitment strategies. It states that it is mostly witches, as opposed to the Devil, who do the recruiting, by making something go wrong in the life of a respectable matron that makes her consult the knowledge of a witch, or by introducing young maidens to tempting young devils. It details how witches cast spells, and remedies that can be taken to prevent witchcraft, or help those who have been affected by it.

Section III

Section III is the legal part of the Malleus Maleficarum that describes how to prosecute a witch. The arguments are clearly laid for the lay magistrates prosecuting witches. The section offers a step-by-step guide to the conduct of a witch trial, from the method of initiating the process and assembling accusations, to the interrogation (including torture) of witnesses, and the formal charging of the accused. Women who did not cry during their trial were automatically believed to be witches.

Theological foundations and major themes

Jakob Sprenger was an appointed inquisitor for the Rhineland, theology professor and a dean at the University of Cologne in Germany. Heinrich Kraemer (Institoris) was an appointed inquisitor of south Germany, a professor of theology at the University of Salzburg, the leading demonologist and witch-hunter in late medieval Germany. Pope Innocent VIII in papal bull summis desiderantes refers to them both as "beloved sons" and "professors of theology"; also authorizes them to extirpate witchcraft.

Malleus Maleficarum was intended to implement Exodus 22:18: "You shall not permit a sorceress to live." and explicitly argues that Canon Episcopi does not apply to the new, formerly unknown heresy of "modern witchcraft".

Kramer and Sprenger were the first to raise harmful sorcery to the criminal status of heresy. If harmful sorcery is a crime on the order of heresy, Kramer and Sprenger argue, then the secular judges who prosecute it must do so with the same vigor as would the Inquisition in prosecuting a heretic. The Malleus urges them to adopt torture, leading questions, the admission of denunciation as valid evidence, and other Inquisitorial practices to achieve swift results. Moreover, the authors insist that the death penalty for convicted witches is the only sure remedy against withcraft. They maintain that the lesser penalty of banishment prescribed by Canon episcopi for those convicted of harmful sorcery does not apply to the new breed of witches, whose unprecedented evil justifies capital punishment.

The ancient subjects of astronomy, philosophy, and medicine were being reintroduced to the West at this time, as well as a plethora of ancient texts being rediscovered and studied. The Malleus Maleficarum often makes reference to the Bible and Aristotelian thought, and it is heavily influenced by the philosophical tenets of Neoplatonism. It also mentions astrology and astronomy, which had recently been reintroduced to the West by the ancient works of Pythagoras. The Malleus is also heavily influenced by the subjects of divination, astrology, and healing rituals the Church inherited from antiquity.

Torture and confessions

See also: Strappado (torture), Rack (torture), and Category:Medieval instruments of torture

Malleus recommended not only torture but also deception in order to obtain confessions: "And when the implements of torture have been prepared, the judge, both in person and through other good men zealous in the faith, tries to persuade the prisoner to confess the truth freely; but, if he will not confess, he bid attendants make the prisoner fast to the strappado or some other implement of torture. The attendants obey forthwith, yet with feigned agitation. Then, at the prayer of some of those present, the prisoner is loosed again and is taken aside and once more persuaded to confess, being led to believe that he will in that case not be put to death."

All confessions acquired with the use of tortures had to be confirmed: "And note that, if he confesses under the torture, he must afterward be conducted to another place, that he may confirm it and certify that it was not due alone to the force of the torture."

However, if there was no confirmation tortures could not be repeated but it was allowed to continue them at the specified day: "But, if the prisoner will not confess the truth satisfactorily, other sorts of tortures must be placed before him, with the statement that unless he will confess the truth, he must endure these also. But, if not even thus he can be brought into terror and to the truth, then the next day or the next but one is to be set for a continuation of the tortures - not a repetition, for it must not be repeated unless new evidences produced. The judge must then address to the prisoners the following sentence: We, the judge, etc., do assign to you, such and such a day for the continuation of the tortures, that from your own mouth the truth may be heard, and that the whole may be recorded by the notary."

Victims

The treatise describes how women and men become inclined to practice witchcraft. The text argues that women are more susceptible to demonic temptations through the manifold weaknesses of their gender. It was believed that they were weaker in faith and more carnal than men. Michael Bailey claims that most of the women accused as witches had strong personalities and were known to defy convention by overstepping the lines of proper female decorum. After the publication of the Malleus, it seems as though about three quarters of those individuals prosecuted as witches were women.

Indeed, the very title of the Malleus Maleficarum is feminine, alluding to the idea that it was women who were the villains. Otherwise, it would be the Malleus Maleficorum (the masculine form of the Latin noun maleficus or malefica, 'witch'). In Latin, the feminine "Maleficarum" would only be used for women, while the masculine "Maleficorum" could be used for men alone or for both sexes if together. The Malleus Maleficarum accuses male and female witches of infanticide, cannibalism and casting evil spells to harm their enemies as well as having the power to steal a man's penis. It goes on to give accounts of witches committing these crimes.

Arguments favoring discrimination against women are explicit in the handbook. Those arguments are not novel but constitute a selection from the long tradition of Western misogynist writings. However, according to Brauner, they are combined to produce new meanings and result in a comprehensive theory. It mixes elements borrowed from Formicarius (1435), Preceptorium divinae legis (1475) and Lectiones super ecclesiastes (1380).

Kramer and Sprenger develop a powerful gender-specific theory of witchcraft based on a hierarchical and dualistic view of the world. Everything exists in pairs of opposites: God and Satan, Mary and Eve, and men (or virgins) and women. Each positive principle in a pair is delineated by its negative pole. Perfection is defined not as the integration or preservation of opposites, but rather as the extermination of the negative element in a polar pair. Because women are the negative counterpart to men, they corrupt male perfection through witchcraft and must be destroyed.

Although authors give many examples of male witchery in second part of the handbook, those trials that are independently confirmed and that were led by Kramer himself are related to persecution of women exclusively. They took place in Ravensburg near Constance (1484) and Innsbruck (since 1485). According to Brauner, trial records confirm that Kramer believed that women are by nature corrupt and evil. His position was in harmony with the scholastic theory at the time. In contrast, Sprenger never participated in a witch trial. Kramer and Sprenger use a metaphor of a world turned upside down by women of which concubines are the most wicked, followed by midwives and then by wives who dominate their husbands. Authors warn of imminent arrival of the apocalypse foretold in the Bible and that men risk bewitchment that leads to impotence and sensation of castration. Brauner explains authors' prescription on how a woman can avoid becoming a witch:

According to the Malleus, the only way a woman can avoid succumbing to her passions - and becoming a witch - is to embrace a life of devout chastity in religious retreat. But the monastic life is reserved to the spiritually gifted few. Therefore, most women are doomed to become witches, who cannot be redeemed; and the only recourse open to the authorities is to ferret out and exterminate all witches.

Demons

Demons are the ones who tempt humans to sorcery and are the main figures in the witches' vows. They interact with witches, usually sexually. The book claims that it is normal for all witches "to perform filthy carnal acts with demons." This is a major part of human-demon interaction and demons do it "not for the sake of pleasure, but for the sake of corrupting." It is worth noting that not all demons do such things. The book claims that "the nobility of their nature causes certain demons to balk at committing certain actions and filthy deeds." Though the work never gives a list of names or types of demons, like some demonological texts or spellbooks of the era, such as the Liber Juratus, it does indicate different types of demons. For example, it devotes large sections to incubi and succubi and questions regarding their roles in pregnancies, the submission of witches to incubi, and protections against them.

Witches

Malleus Maleficarum has a very specific conception of what a witch is, one that differs dramatically from earlier times. The word used, Malefica, carries the implicit condemnation that other words also referring to women with supernatural powers, lacked. The conception of witches and of magic by extension is one of evil. It differs from earlier conceptions of witchcraft that were much more generalized. This is the point in history where "witchcraft constituted an independent antireligion". The witch lost her powerful position vis-a-vis the deities; the ability to force the deities comply with her wishes was replaced by a total subordination to the devil. In short, the witch became Satan's puppet." This conception of witches was "part of a conception of magic that is termed by scholars as 'Satanism' or 'diabolism'". In this conception, a witch was a member of "a malevolent society presided over by Satan himself and dedicated to the infliction of malevolent acts of sorcery (malefica) on others."

Witches were usually female. The reasons for this is the suggestion that women are "prone to believing and because the demon basically seeks to corrupt the faith, he assails them in particular." They also have a "temperament towards flux" and "loose tongues". They "are defective in all the powers of both soul and body" and are stated to be more lustful than men. The major reason is that at the foundation of sorcery is denial of faith and "woman, therefore, is evil as a result of nature because she doubts more quickly in the faith." Men could be witches, but were considered rarer, and the reasons were also different. The most common form of male witch mentioned in the book is the sorcerer-archer. The book is rather unclear, but the impetus behind male witches seems to come more from desire for power than from disbelief or lust, as it claims is the case for female witches.

Popularity and influence

Gender-specific theory developed in Malleus Maleficarum laid the foundations for widespread consensus in early modern Germany on the evil nature of women as witches. Later works on witchcraft have not agreed entirely with Malleus but none of them challenged the view that women were more inclined to be witches than men. It was perceived as intuitive and all-accepted so that very few authors saw the need to explain why women are witches. Those who did, attributed female witchery to the weakness of body and mind (old medieval explanation) and a few to female sexuality.

Some authors argue that the book's publication was not as influential as earlier authors believed. According to MacCulloch, the Malleus Maleficarum was one of several key factors contributing to the witch craze, along with popular superstition, and tensions created by the Reformation. However, according to Encyclopedia Britannica:

The Malleus went through 28 editions between 1486 and 1600 and was accepted by Roman Catholics and Protestants alike as an authoritative source of information concerning Satanism and as a guide to Christian defense.

— Encyclopedia Britannica

Factors stimulating widespread use

Between 1487 and 1520, twenty editions of the Malleus Maleficarum were published, and another sixteen between 1574 and 1669. The Malleus Maleficarum was able to spread throughout Europe rapidly in the late 15th and at the beginning of the 16th century due to the innovation of the printing press in the middle of the 15th century by Johannes Gutenberg. The invention of printing some thirty years before the first publication of the Malleus Maleficarum instigated the fervor of witch hunting, and, in the words of Russell, "the swift propagation of the witch hysteria by the press was the first evidence that Gutenberg had not liberated man from original sin."

The late 15th century was also a period of religious turmoil. The Malleus Maleficarum and the witch craze that ensued took advantage of the increasing intolerance of the Reformation and Counter-Reformation in Europe, where the Protestant and Catholic camps, pitted against one another, each zealously strove to maintain what they each deemed to be the purity of faith.

Translations

The Latin book was firstly translated by de [J. W. R. Schmidt] into German in 1906; an expanded edition of three volumes was published in 1923. Montague Summers was responsible for the first English translation in 1928.

- Henricus Institoris and Jacobus Sprenger, Malleus maleficarum, ed. and trans. by Christopher S. Mackay, 2 vols (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006) (edition in vol. 1 and translation in vol. 2)

- The Hammer of Witches: A Complete Translation of the Malleus maleficarum, trans. by Christopher S. Mackay (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009)

- The Malleus Maleficarum, ed. and trans. by P.G. Maxwell-Stuart (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2007) (translation only)

Some translations ignore the most brutal third section and may be misleading to the reader. For instance, sections one and three have never been translated into polish.

See also

- Friedrich Spee

- Witch-hunts

- Witch trials in the early modern period

- Witchcraft

- Rack (torture)

- European witchcraft

- Pope Innocent VIII

- Witchcraft and divination in the Bible

- Christian views on magic

- Torture of witches

- Discoverie of Witchcraft

References

Notes

- "In its own day it was never accorded the unquestioned authority that modern scholars have sometimes given it. Theologians and jurists respected it as one among many informative books; its particular savage misogyny and its obsession with impotence were never fully accepted", Monter, The Sociology of Jura Witchcraft, in The Witchcraft Reader, p. 116 (2002)

Citations

- The English translation is from this note to Summers' 1928 introduction.

- Translator Montague Summers consistently uses "the Malleus Maleficarum" (or simply "the Malleus") in his 1928 and 1948 introductions. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-07-18. Retrieved 2016-02-05.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2007-06-07. Retrieved 2007-06-01.{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - In his translation of the Malleus Maleficarum, Christopher S. Mackay explains the terminology at length – sorcerer is used to preserve the relationship of the Latin terminology. '"Malefium" = act of sorcery (literally an act of 'evil-doing'), while "malefica" = female performers of sorcery (evil deeds) and "maleficus" = male performer of evil deeds; sorcery, sorceress, and sorcerer."

- Ruickbie (2004), 71, highlights the problems of dating; Ankarloo (2002), 239

- Behringer, Wolfgang. "Malleus Maleficarum", p. 2.

- Behringer, Wolfgang. "Malleus Maleficarum", p. 3.

- Klose, Hans-Christian. “Die angebliche Mitarbeit des Dominikaners Jakob Sprenger am Hexenhammer, nach einem alten Abdinghofer Brief.” pp. 197–205 in Paderbornensis Ecclesia. Beiträge zur Geschichte des Erzbistums Paderborn. Festschrift für Lorenz Kardinal Jäger zum 80. Geburtstag. Edited by Paul-Werner Scheele.

- Behringer, Wolfgang. "Malleus Maleficarum", p. 3.

- "The latter was at least partly a forgery, because two of its supposed authors (Thomas de Scotia and Johann von Wörde) later denied any participation." - Behringer, Wolfgang. "Malleus Maleficarum" p. 3.

- Jolly, Raudvere, & Peters(eds.), "Witchcraft and magic in Europe: the Middle Ages", page 241 (2002)

- Burns, William. "Witch Hunts in Europe and America: An Encyclopedia", pp. 143-144.

- Pavlac (2009), p. 29.

- Pavlac (2009), p. 31.

- ^ MacCulloch, Diarmaid (2004). Reformation: Europes House Divided. Vintage Books, 2006. pp. 563–68. ISBN 0-14-028534-2.

- Trevor-Roper (1969), pp. 102–105.

- Ankarloo & Clark (2002), p. 240.

- ^ Russell, 229

- Philip Schaff, History of the Christian Church, vol. vi, Eerdmans, Grand Rapids, 1994, s. 514-527

- ^ Template:PDF: Defining Witchcraft. Elizabeth Mack.

- Russell (1972), 230

- Mackay (2006), p. 103.

- Mackay (2006), p. 128.

- "So successful was this stroke of advertising strategy that the authors hardly even needed the approval of the Cologne University theologians, but just for good measure Institoris forged a document granting their apparently unanimous approbation.", Joyy et al., 'Witchcraft and Magic In Europe', p. 115 (2002)

- Bailey (2003), p. 30.

- Behringer, Wolfgang. "Malleus Maleficarum", p. 7.

- 'In 1538 the Spanish Inquisition cautioned its members not to believe everything the Malleus said, even when it presented apparently firm evidence.', Jolly, Raudvere, & Peters(eds.), 'Witchcraft and magic in Europe: the Middle Ages', page 241 (2002)

- Russell, 232

- Russell, 279

- Broedel (2003), p. 20.

- ^ Broedel (2003), p. 22.

- ^ Broedel, 30

- Mackay (2006), p. 214.

- Broedel (2003), p. 34.

- Mackay (2006), p. 502.

- Britannica: "The Malleus was the work of two Dominicans: Johann Sprenger, dean of the University of Cologne in Germany, and Heinrich (Institoris) Kraemer, professor of theology at the University of Salzburg, Austria"

- Burns (2003), p. 158': "Sprenger, a theology professor at Cologne, had already been appointed inquisitor for the Rhineland in 1470."

- Britannica: "The Malleus was the work of two Dominicans: Johann Sprenger, dean of the University of Cologne in Germany, and Heinrich (Institoris) Kraemer, professor of theology at the University of Salzburg, Austria"

- Burns (2003), p. 158: "The fifteenth-century German Dominican inquisitor Heinrich Kramer, was a leading demonologist and witch-hunter in late medieval Germany."

- Halsall (1996), Innocent VIII: BULL Summis desiderantes, Dec. 5th, 1484: "And, although our beloved sons Henricus Institoris and Jacobus Sprenger, of the order of Friars Preachers, professors of theology, have been and still are deputed by our apostolic letters as inquisitors of heretical pravity, the former in the aforesaid parts of upper Germany, including the provinces, cities, territories, dioceses, and other places as above, and the latter throughout certain parts of the course of the Rhine;"

- Britannica: "In 1484 Pope Innocent VIII issued the bull Summis Desiderantes, in which he deplored the spread of witchcraft in Germany and authorized Sprenger and Kraemer to extirpate it."

- Britannica: "The Malleus codified the folklore and beliefs of the Alpine peasants and was dedicated to the implementation of Exodus 22:18: “You shall not permit a sorceress to live.”"

- ^ Brauner (2001), pp. 33–34.

- Kieckhefer (2000), p. 145.

- Kieckhefer (2000), p. 146.

- Ankarloo & Clark (2002), p. 77.

- ^ Halsall (1996), Extracts from THE HAMMER OF WITCHES , 1486.

- Bailey (2003), p. 49.

- Bailey (2003), p. 51.

- Russell, 145

- Maxwell-Stewart (2001), p. 30.

- ^ Brauner (2001), p. 38.

- Brauner (2001), p. 45.

- Brauner (2001), p. 47.

- Brauner (2001), p. 44.

- Brauner (2001), pp. 42–43.

- Brauner (2001), p. 41.

- Mackay (2009), p. 125. sfnp error: no target: CITEREFMackay2009 (help)

- Mackay (2009), p. 283. sfnp error: no target: CITEREFMackay2009 (help)

- Mackay (2009), p. 309. sfnp error: no target: CITEREFMackay2009 (help)

- Ben-Yehuda (1980), p. 3. sfnp error: no target: CITEREFBen-Yehuda1980 (help)

- Mackay (2009), p. 19. sfnp error: no target: CITEREFMackay2009 (help)

- ^ Mackay (2009), p. 164. sfnp error: no target: CITEREFMackay2009 (help)

- Mackay (2009), p. 166. sfnp error: no target: CITEREFMackay2009 (help)

- Brauner (2001), p. 49.

- ^ Brauner (2001), p. 48.

- "The effect that the book had on witch-hunting is difficult to determine. It did not open the door 'to almost indiscriminate prosecutions' or even bring about an immediate increase in the number of trials. In fact its publication in Italy was followed by a noticeable reduction in witchcraft cases", Levack, The Witch-Hunt In Early Modern Europe, p. 55 (2nd edition 1995)

- "Nor was the Malleus immediately regarded as a definitive work. Its appearance triggered no prosecutions in areas where there had been none earlier, and in some cases its claims encountered substantial skepticism (for Italy, Paton 1992:264–306). In 1538 the Spanish Inquisition cautioned its members not to believe everything the Malleus said, even when it presented apparently firm evidence", Joyy et al., Witchcraft and Magic In Europe, p. 241 (2002)

- Russell, 79

- Russell, 234

- Henningsen (1980), p. 15.

Bibliography

- "Malleus maleficarum". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- Halsall, Paul, ed. (1996). "Witchcraft Documents [15th Century]". Internet Medieval Sourcebook. Fordham University Center for Medieval Studies.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Burns, William (2003). Witch Hunts in Europe and America: An Encyclopedia. Greenwood. ISBN 0-3133-2142-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Brauner, Sigrid (2001). Fearless Wives and Frightened Shrews: The Construction of the Witch in Early Modern Germany. University of Massachusetts Press. ISBN 1-5584-9297-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ankarloo, Bengt; Clark, Stuart, eds. (2002). Witchcraft and Magic in Europe, Volume 3: The Middle Ages. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0-8122-1786-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bailey, Michael D. (2003). Battling Demons: Witchcraft, Heresy, and Reform in the Late Middle Ages. Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 0-271-02226-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Broedel, Hans Peter (2003). The Malleus Maleficarum and the Construction of Witchcraft: Theology and Popular Belief. Manchester University Press. ISBN 9780719064418.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Henningsen, Gustav (1980). The Witches' Advocate: Basque Witchcraft and the Spanish Inquisition. University of Nevada Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kieckhefer, Richard (2000). Magic in the Middle Ages. Cambridge University Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Mackay, Christopher S. (2006). Malleus Maleficarum (2 volumes). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-85977-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) Template:La icon Template:En icon - Maxwell-Stewart, P. G. (2001). Witchcraft in Europe and the New World. Palgrave.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Pavlac, Brian (2009). Witch Hunts in the Western World: Persecution and Punishment from the Inquisition through the Salem Trials: Persecution and Punishment from the Inquisition through the Salem Trials. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9780313348747.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Trevor-Roper, H. R. (1969). The European Witch-Craze: of the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries and Other Essays. Harper Collins. ISBN 0-06-131416-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Further reading

- Flint, Valerie. The Rise of Magic in Early Medieval Europe. Princeton University Press. Princeton, NJ. 1991

- Hamilton, Alastair (May 2007). "Review of Malleus Maleficarum edited and translated by Christopher S. Mackay and two other books". Heythrop Journal. 48 (3): 477–479. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2265.2007.00325_12.x.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|quotes=(help)

(payment required) - Institoris, Heinrich; Jakob Sprenger (1520). Malleus maleficarum, maleficas, & earum haeresim, ut phramea potentissima conterens. Excudebat Ioannes Gymnicus.

- This is the edition held by the University of Sydney Library.

- Ruickbie, Leo (2004). Witchcraft Out of the Shadows. Robert Hale. ISBN 0-7090-7567-7.

- Russell, Jeffrey Burton (1972 repr. 1984). Witchcraft in the Middle Ages. Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-9289-0.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) (bibrec) - Summers, Montague (1948 repr. 1971). The Malleus Maleficarum of Kramer and Sprenger. ed. and trans. by Summers. Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-22802-9.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - Thurston, Robert W. (November 2006). "The world, the flesh and the devil". History Today. 56 (11): 51–57.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|quotes=(help) (payment required for full text)

External links

- Malleus Maleficarum – Online version of Latin text and scanned pages of Malleus Maleficarum published in 1580.

- Malleus Maleficarum – Online and downloadable scan of original Latin edition of 1490.

- English translation

| Magic and witchcraft | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Types |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Practices | |||||||||||||||||

| Objects | |||||||||||||||||

| Folklore and mythology | |||||||||||||||||

| Major historic treatises |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Persecution |

| ||||||||||||||||

| In popular culture | |||||||||||||||||

| Related | |||||||||||||||||