This is an old revision of this page, as edited by D4iNa4 (talk | contribs) at 09:58, 2 May 2018 (rv ban evading sock). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 09:58, 2 May 2018 by D4iNa4 (talk | contribs) (rv ban evading sock)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)

| Part of a series on |

| Shaivism |

|---|

|

|

DeitiesParameshvara (Supreme being) |

| Scriptures and texts |

Philosophy

|

| Practices |

Schools

Saiddhantika Non - Saiddhantika

|

| Scholars |

| Related |

|

|

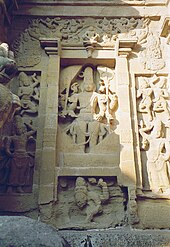

Lingam (Sanskrit: लिंगम्, IAST: liṅgaṃ, lit. "sign, symbol or mark"; also linga, Shiva linga), is an abstract or aniconic representation of the Hindu deity Shiva, used for worship in temples, smaller shrines, or as self-manifested natural objects. In traditional Indian society, the linga is seen as a symbol of the energy and potential of Shiva himself.

The lingam is often represented as resting on a disc shaped platform.

Definition

The lingam is a column-like or oval (egg-shaped) symbol of Shiva, the Formless All-pervasive Reality, made of stone, metal, or clay. The Shiva Linga is a symbol of Lord Shiva – a mark that reminds of the Omnipotent Lord, which is formless. In Shaivite Hindu temples, the linga is a smooth cylindrical mass symbolising Shiva. It is found at the centre of the temple, often resting in the middle of a rimmed, disc-shaped structure, a representation of Shakti.

Origin

Terracotta Shiva Linga figurines found in excavations at Indus Valley Civilization site of Kalibangan and other sites provide evidence of early Shiva Linga worship from circa 3500 BCE to 2300 BCE.

Anthropologist Christopher John Fuller wrote that although most sculpted images (murtis) are anthropomorphic, the aniconic Shiva Linga is an important exception. Some believe that linga-worship was a feature of indigenous Indian religion.

There is a hymn in the Atharvaveda that praises a pillar (Sanskrit: stambha), and this is one possible origin of linga worship. Some associate Shiva-Linga with this Yupa-Stambha, the sacrificial post. In the hymn, a description is found of the beginning-less and endless Stambha or Skambha, and it is shown that the said Skambha is put in place of the eternal Brahman. The Yupa-Skambha gave place in time to the Shiva-Linga. In the Linga Purana the same hymn is expanded in the shape of stories meant to establish the glory of the great Stambha and the supreme nature of Mahâdeva (the Great God, Shiva).

The Hindu scripture Shiva Purana describes the origin of the lingam, known as Shiva-linga, as the beginning-less and endless cosmic pillar (Stambha) of fire, the cause of all causes. Lord Shiva is pictured as emerging from the Lingam – the cosmic pillar of fire – proving his superiority over the gods Brahma and Vishnu. This is known as Lingodbhava. The Linga Purana also supports this interpretation of lingam as a cosmic pillar, symbolizing the infinite nature of Shiva. According to the Linga Purana, the lingam is a complete symbolic representation of the formless Universe Bearer – the oval-shaped stone is the symbol of the Universe, and the bottom base represents the Supreme Power that holds the entire Universe in it. A similar interpretation is also found in the Skanda Purana: "The endless sky (that great void which contains the entire universe) is the Linga, the Earth is its base. At the end of time the entire universe and all the Gods finally merge in the Linga itself." In yogic lore, the linga is considered the first form to arise when creation occurs, and also the last form before the dissolution of creation. It is therefore seen as an access to Shiva or that which lies beyond physical creation. In the Mahabharata, at the end of Dwaraka Yuga, Lord Shiva says to his disciples that in the coming Kali Yuga, He would not appear in any particular form, but instead as the formless and omnipresent.

Historical period

According to Shaiva Siddhanta, which was for many centuries the dominant school of Shaiva theology and liturgy across the Indian subcontinent (and beyond it in Cambodia), the linga is the ideal substrate in which the worshipper should install and worship the five-faced and ten-armed Sadāśiva, the form of Shiva who is the focal divinity of that school of Shaivism.

The oldest example of a lingam that is still used for worship is in Gudimallam. It dates to the 2nd century BC. A figure of Shiva is carved into the front of the lingam.

The lingam is the considered to be the primordial representation of pure form devoid of energy.

Making of Lingam according to Scriptures

The Saiva Agamas says "one can worship this Great God Shiva in the form of a Lingam made of mud or sand, of cow dung or wood, of bronze or black granite stone. But the purest and most sought-after form is the quartz crystal (Sphatika), a natural stone not carved by man but made by nature, gathered molecule by molecule over hundreds, thousands or millions of years, grown as a living body grows, but infinitely more slowly. Such a creation of nature is itself a miracle worthy of worship." Hindu scripture rates crystal as the highest form of Siva Lingam.

Karana Agama, a Shaiva Agama, states in 6th verse that "A temporary Shiva Lingam may be made of 12 different materials: sand, rice, cooked food, river clay, cow dung, butter, rudraksha seeds , ashes, sandalwood, dharba grass, a flower garland or molasses."

Naturally occurring Lingams

An ice lingam at Amarnath in the western Himalayas forms every winter from ice dripping on the floor of a cave and freezing like a stalagmite. It is very popular with pilgrims..

In Kadavul Temple, a 700-pound, 3-foot-tall, naturally formed Spatika(quartz) Lingam is installed. In future this crystal lingam will be housed in the Iraivan Temple. it is claimed as among the largest known sphatika(Quartz) self formed lingams. Hindu scripture rates crystal as the highest form of Siva Lingam.

Shivling, 6,543 metres (21,467 ft), is a mountain in Uttarakhand (the Garhwal region of Himalayas). It arises as a sheer pyramid above the snout of the Gangotri Glacier. The mountain resembles a Shiva lingam when viewed from certain angles, especially when travelling or trekking from Gangotri to Gomukh as part of a traditional Hindu pilgrimage.

A lingam is also the basis for the formation legend (and name) of the Borra Caves in Andhra Pradesh.

See also

- Axis mundi

- Banalinga

- Hindu iconography

- Jangam

- Jyotirlinga

- Lingayatism

- Mukhalinga

- Pancharamas

- Shaligram

- Spatika Lingam

References

- Johnson, W.J. (2009). A dictionary of Hinduism (1st ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191726705. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|subscription=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help)(subscription or UK public library membership required) - Fowler, Jeaneane (1997). Hinduism : beliefs and practices. Brighton : Sussex Acad. Press. pp. 42–43. ISBN 9781898723608.

- ^ "lingam". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2010.

- Sivananda (1996). Lord Siva and His Worship. Worship of Siva Linga: The Divine Life Trust Society. ISBN 81-7052-025-8.

- Das, Subhamoy. "What is Shiva Linga?". About.com. Retrieved 8 February 2017.

- ^ Blurton, T. R. (1992). "Stone statue of Shiva as Lingodbhava". Extract from Hindu art (London, The British Museum Press). British Museum site. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- Tanga, Surbhi Gupta (August 2016). "Call for an International Museum & Research Center for Harrapan Civilization, at Rakhigarhi" (PDF). INTACH Haryana newsletter. Haryana State Chapter of INTACH: 33–34.

- Lipner, Julius J. (2017). Hindu Images and Their Worship with Special Reference to Vaisnavism: A Philosophical-theological Inquiry. London ; New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. p. 39. ISBN 9781351967822. OCLC 985345208.

- The Camphor Flame: Popular Hinduism and society in India, pg. 58 at Books.Google.com

- ^ Singh, Nagendra Kr. (1997). Encyclopaedia of Hinduism (1st ed.). New Delhi: Centre for International Religious Studies. p. 1567. ISBN 9788174881687.

- ^ Harding, Elizabeth U. (1998). "God, the Father". Kali: The Black Goddess of Dakshineswar. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 156–157. ISBN 978-81-208-1450-9.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Vivekananda, Swami. "The Paris Congress of the History of Religions". The Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda. Vol. Vol.4.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - Chaturvedi. Shiv Purana (2006 ed.). Diamond Pocket Books. p. 11. ISBN 978-81-7182-721-3.

- "The linga Purana". astrojyoti. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

. It was almost as if the linga had emerged to settle Brahma and Vishnu's dispute. The linga rose way up into the sky and it seemed to have no beginning or end.

- Sivananda, Swami (1996). "Worship of Siva Linga". Lord Siva and His Worship. The Divine Life Trust Society.

- "Reading the Vedic Literature in Sanskrit". is1.mum.edu. Retrieved 2 June 2017.

- "Linga – A Doorway to No-thing". 18 July 2013. Retrieved 11 April 2014.

- Dominic Goodall, Nibedita Rout, R. Sathyanarayanan, S.A.S. Sarma, T. Ganesan and S. Sambandhasivacarya, The Pañcāvaraṇastava of Aghoraśivācārya: A twelfth-century South Indian prescription for the visualisation of Sadāśiva and his retinue, Pondicherry, French Institute of Pondicherry and Ecole française d'Extréme-Orient, 2005, p.12.

- Klostermaier, Klaus K. (2007). A Survey of Hinduism (3. ed.). Albany, N.Y.: State University of New York Press. p. 111. ISBN 978-0-7914-7082-4.

- Elgood, Heather (2000). Hinduism and the Religious Arts. London: Cassell. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-8264-9865-6.

- "A Clear Crystal Vision: The Story of Iraivan's Lingam". himalayanacademy.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - "Gurudeva Siva Vision Day". himalayanacademy.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - "rare crystal lingam".

- "Shiva Lingam Meaning".

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - "Making of Lingam".

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - "Amarnath: Journey to the shrine of a Hindu god". 13 July 2012.

- under the section "GENERAL INTRODUCTION". "Kadavul Hindu Temple". Himalayanacademy.

- "Iraivan Temple In the News".

- "Rare Crystal Siva Lingam Arrives At Hawaii Temple". hinduismtoday.

- "BORRA CAVES". Arakuvalleytourism. section = LEGEND.

Sources

- Basham, A. L. The Wonder That Was India: A survey of the culture of the Indian Sub-Continent before the coming of the Muslims, Grove Press, Inc., New York (1954; Evergreen Edition 1959).

- Schumacher, Stephan and Woerner, Gert. The Encyclopedia of Eastern Philosophy and Religion, Buddhism, Taoism, Zen, Hinduism, Shambhala, Boston, (1994) ISBN 0-87773-980-3.

- Chakravarti, Mahadev. The Concept of Rudra-Śiva Through the Ages, Delhi: Motilal Banarasidass (1986), ISBN 8120800532.

- Davis, Richard H. (1992). Ritual in an Oscillating Universe: Worshipping Śiva in Medieval India. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691073866.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Drabu, V.N. Śaivāgamas: A Study in the Socio-economic Ideas and Institutions of Kashmir (200 B.C. to A.D. 700), New Delhi: Indus Publishing (1990), ISBN 8185182388.

- Ram Karan Sharma. Śivasahasranāmāṣṭakam: Eight Collections of Hymns Containing One Thousand and Eight Names of Śiva. With Introduction and Śivasahasranāmākoṣa (A Dictionary of Names). (Nag Publishers: Delhi, 1996). ISBN 81-7081-350-6. This work compares eight versions of the Śivasahasranāmāstotra. The preface and introduction Template:En icon by Ram Karan Sharma provide an analysis of how the eight versions compare with one another. The text of the eight versions is given in Sanskrit.

- Kramrisch, Stella (1988). The Presence of Siva. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 9788120804913.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)

Further reading

- Daniélou, Alain (1991). The Myths and Gods of India: The Classic Work on Hindu Polytheism. Inner Traditions / Bear & Company. pp. 222–231. ISBN 0-89281-354-7Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Versluis, Arthur (2008), The Secret History of Western Sexual Mysticism: Sacred Practices and Spiritual Marriage, Destiny Books, ISBN 978-1-59477-212-2

External links

| Shaivism | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History | |||||||||||

| Deities |  | ||||||||||

| Texts | |||||||||||

| Mantra/Stotra | |||||||||||

| Traditions | |||||||||||

| Festivals and observances | |||||||||||

| Shiva temples |

| ||||||||||

| Related topics | |||||||||||

| Worship in Hinduism | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main topics | |||||||

| Rituals |

| ||||||

| Mantras | |||||||

| Objects | |||||||

| Materials | |||||||

| Instruments | |||||||

| Iconography | |||||||

| Places | |||||||

| Roles | |||||||

| Sacred animals | |||||||

| Sacred plants |

| ||||||

| See also | |||||||