This is an old revision of this page, as edited by 68.198.161.155 (talk) at 05:57, 25 February 2019 (YHWH LORD GOD WILLING: YHWH LORD GOD (FATHER SON SPIRIT KNOWN/SHOWN) is Real, and One. worship and serve YHWH Alone. my bad as applicable, Good YHWH LORD GOD Always as He Wills). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 05:57, 25 February 2019 by 68.198.161.155 (talk) (YHWH LORD GOD WILLING: YHWH LORD GOD (FATHER SON SPIRIT KNOWN/SHOWN) is Real, and One. worship and serve YHWH Alone. my bad as applicable, Good YHWH LORD GOD Always as He Wills)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) Ancient Greek of winemaking and wine "Bacchus" redirects here. For other uses, see Bacchus (disambiguation). "Bassareus" redirects here. For the genus of beetles, see Bassareus (beetle). This article is about the Greco-Roman. For other uses of the names "Dionysus" and "Dionysos", see Dionysos (disambiguation). For other uses of the theophoric name "Dionysius", see Dionysius (disambiguation).| This article may need to be rewritten to comply with Misplaced Pages's quality standards. You can help. The talk page may contain suggestions. (February 2018) |

| Part of a series on |

| Greek mythology |

|---|

Theseus slays the Minotaur under the gaze of Athena Theseus slays the Minotaur under the gaze of Athena |

| Deities |

| Heroes and heroism |

| Related |

|

|

Dionysus (/daɪ.əˈnaɪsəs/; Template:Lang-grc-gre Dionysos) is the of the grape-harvest, winemaking and wine, of fertility, ritual madness, religious ecstasy, and theatre in ancient Greek religion and myth. Wine played an important role in Greek culture, and the cult of Dionysus was the main religious focus for its unrestrained consumption. His worship became firmly established in the seventh century BC. He may have been worshipped as early as c. 1500–1100 BC by Mycenaean Greeks; traces of Dionysian-type cult have also been found in ancient Minoan Crete. His origins are uncertain, and his cults took many forms; some are described by ancient sources as Thracian, others as Greek. In some cults, he arrives from the east, as an Asiatic foreigner; in others, from Ethiopia in the South. Some scholars believe that Dionysus is a syncretism of a local Greek nature and a more powerful from Thrace or Phrygia such as Sabazios or Zalmoxis. His festivals were the driving force behind the development of Greek theatre.

He is also known as Bacchus (/ˈbækəs/ or /ˈbɑːkəs/; Template:Lang-el, Bakkhos), the name adopted by the Romans As Eleutherios ("the liberator"), his wine, music and ecstatic dance free his followers from self-conscious fear and care, and subvert the oppressive restraints of the powerful.

Dionysus is generally depicted in myth as the son of Zeus and the mortal Semele, although in the Orphic tradition, he was identified as the son of Zeus and Persephone. In the Eleusinian Mysteries he was identified with Iacchus, the son (or, alternately, husband) of Demeter.

Etymology

The dio- element has been associated since antiquity with Zeus (genitive Dios). The earliest attested form of the name is Mycenaean Greek 𐀇𐀺𐀝𐀰, di-wo-nu-so, written in Linear B syllabic script, presumably for /Diwo(h)nūsoio/. This is attested on two tablets that had been found at Mycenaean Pylos and dated to the 12th or 13th century BC, but at the time, there could be no certainty on whether this was indeed a theonym. But the 1989–90 Greek-Swedish Excavations at Kastelli Hill, Chania, unearthed, inter alia, four artefacts bearing Linear B inscriptions; among them, the inscription on item KH Gq 5 is thought to confirm Dionysus's early worship.

Later variants include Dionūsos and Diōnūsos in Boeotia; Dien(n)ūsos in Thessaly; Deonūsos and Deunūsos in Ionia; and Dinnūsos in Aeolia, besides other variants. A Dio- prefix is found in other names, such as that of the Dioscures, and may derive from Dios, the genitive of the name of Zeus. The second element -nūsos is associated with Mount Nysa, the birthplace of the in Greek mythology, where he was nursed by nymphs (the Nysiads), but according to Pherecydes of Syros, nũsa was an archaic word for "tree".

Nonnus, in his Dionysiaca, writes that the name Dionysus means "Zeus-limp" and that Hermes named the new born Dionysus this, "because Zeus while he carried his burden lifted one foot with a limp from the weight of his thigh, and nysos in Syracusan language means limping". In his note to these lines, W. H. D. Rouse writes "It need hardly be said that these etymologies are wrong". The Suda, a Byzantine encyclopedia based on classical sources, states that Dionysus was so named "from accomplishing for each of those who live the wild life. Or from providing everything for those who live the wild life."

R. S. P. Beekes has suggested a Pre-Greek origin of the name.

The cult of Dionysus was closely associated with trees, specifically the fig tree, and some of his bynames exhibit this, such as Endendros "he in the tree" or Dendritēs, "he of the tree". Peters suggests the original meaning as "he who runs among the trees", or that of a "runner in the woods". Janda (2010) accepts the etymology but proposes the more cosmological interpretation of "he who impels the (world-)tree". This interpretation explains how Nysa could have been re-interpreted from a meaning of "tree" to the name of a mountain: the axis mundi of Indo-European mythology is represented both as a world-tree and as a world-mountain.

Iconography

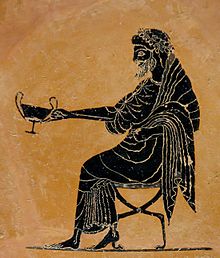

The earliest cult images of Dionysus show a mature male, bearded and robed. He holds a fennel staff, tipped with a pine-cone and known as a thyrsus. Later images show him as a beardless, sensuous, naked or half-naked androgynous youth: the literature describes him as womanly or "man-womanish". In its fully developed form, his central cult imagery shows his triumphant, disorderly arrival or return, as if from some place beyond the borders of the known and civilized. His procession (thiasus) is made up of wild female followers (maenads) and bearded satyrs with erect penises; some are armed with the thyrsus, some dance or play music. The himself is drawn in a chariot, usually by exotic beasts such as lions or tigers, and is sometimes attended by a bearded, drunken Silenus. This procession is presumed to be the cult model for the followers of his Dionysian Mysteries. Dionysus is represented by city religions as the protector of those who do not belong to conventional society and he thus symbolizes the chaotic, dangerous and unexpected, everything which escapes human reason and which can only be attributed to the unforeseeable action of the s.

The bull, serpent, tiger, ivy, and wine are characteristic of Dionysian iconography. Dionysus is also strongly associated with satyrs, centaurs, and sileni. He is often shown riding a leopard, wearing a leopard skin, or in a chariot drawn by panthers, and may also be recognized by the thyrsus he carries. Besides the grapevine and its wild barren alter-ego, the toxic ivy plant, both sacred to him, the fig was also his symbol. The pinecone that tipped his thyrsus linked him to Cybele.

Epithets

Dionysus was variably known with the following epithets:

Acratophorus, ("giver of unmixed wine"), at Phigaleia in Arcadia.

Acroreites at Sicyon.

Adoneus, a rare archaism in Roman literature, a Latinised form of Adonis, used as epithet for Bacchus.

Aegobolus ("Goat-shooter") at Potniae, in Boeotia.

Aesymnetes ("ruler" or "lord") at Aroë and Patrae in Achaea.

Agrios ("wild"), in Macedonia.

Bassareus, a Thracian name for Dionysus, which derives from bassaris or "fox-skin", which item was worn by his cultists in their mysteries.

Briseus ("he who prevails") in Smyrna.

Bromios ("Roaring" as of the wind, primarily relating to the central death/resurrection element of the myth, but also the transformations into lion and bull, and the boisterousness of those who drink alcohol. Also cognate with the "roar of thunder", which refers to Dionysus' father, Zeus "the thunderer".)

Choiropsalas χοιροψάλας ("pig-plucker": Greek χοῖρος = "pig," also used as a slang term for the female genitalia). A reference to Dionysus's role as a fertility .

Chthonios ("the subterranean")

Dendrites ("he of the trees"), as a fertility .

Dithyrambos, used at his festivals, referring to his premature birth.

Eleutherios ("the liberator"), an epithet shared with Eros.

Endendros ("he in the tree").

Enorches ("with balls," with reference to his fertility, or "in the testicles" in reference to Zeus' sewing the baby Dionysus "into his thigh", understood to mean his testicles). used in Samos and Lesbos.

Erikryptos ("completely hidden"), in Macedonia.

Euius (Euios), in Euripides' play, The Bacchae.

Iacchus, a possible epithet of Dionysus, associated with the Eleusinian Mysteries. In Eleusis, he is known as a son of Zeus and Demeter. The name "Iacchus" may come from the Ιακχος (Iakchos), a hymn sung in honor of Dionysus.

Liknites ("he of the winnowing fan"), as a fertility connected with mystery religions. A winnowing fan was used to separate the chaff from the grain.

Lyaeus, or Lyaios (Λυαῖος, "deliverer", literally "loosener"), one who releases from care and anxiety.

Melanaigis ("of the black goatskin") at the Apaturia festival.

Morychus (Μόρυχος, "smeared") in Sicily, because his icon was smeared with wine lees at the vintage.

Oeneus, as of the wine press.

Pseudanor (literally "false man", referring to his feminine qualities), in Macedonia.

In the Greek Dionysus (along with Zeus) absorbs the role of Sabazios, a Thracian/Phrygian . In the Roman mythology, Sabazius became an alternative name for Bacchus.

Mythology

Birth narratives

Various different accounts and traditions existed in the ancient world regarding the parentage of Dionysus, complicated by his one or several rebirths, often said to involve different parents. By the 1st century BC, some mythographers had attempted to harmonize the various accounts of Dionysus' birth into a single narrative involving not only multiple births, but two or three distinct manifestations of the on earth throughout history in different lifetimes. The historian Diodorus Siculus said that according to "some writers of myths" there were two s named Dionysus, an older one, who was the son of Zeus and Persephone, but that the "younger one also inherited the deeds of the older, and so the men of later times, being unaware of the truth and being deceived because of the identity of their names thought there had been but one Dionysus." He also said that Dionysus "was thought to have two forms...the ancient one having a long beard, because all men in early times wore long beards, the younger one being youthful and effeminate and young."

The first Dionysus, according to this scheme, was born in India to Ammon and Amaltheia, and depicted with a long beard in the Indian fashion of the time. It was there that he first taught mortals how to cultivate fruit crops and make wine. He later traveled the world with his retinue spreading this knowledge. The second Dionysus said to have been born to Zeus and Persephone (or, alternately, to Demeter), as in the Orphic tradition. It was this Dionysus who was said to have taught mortals how use use oxen to plow the fields, rather than doing so by hand. His worshipers were said to have honored him for this by depicting him with horns. The third Dionysus was said to have been born of Zeus and Semele in Thebes, in the manner described by Hesiod and the Homeric Hymns. It was said that this third Dionysus was the one portrayed in the majority of classical literature.

Ammon and Amaltheia

According to Diodorus, the "first" Dionysus was the son of Ammon, who Diodorus regarded both as the creator and a quasi-historical king of Libya. In Diodorus' account, Ammon had married the dess Rhea, but he had an affair with Amaltheia, who bore Dionysus. Ammon feared Rhea's wrath if she were to discover the child, so he took the infant Dionysus to Nysa (Dionysus' traditional childhood home). Ammon brought Dionysus into a cave where he was to be cared for by Nysa, a daughter of the hero Aristaeus.

Dionysus grew famous due to his skill in the arts, his beauty, and his strength. It was said that he discovered the art of winemaking during his boyhood. His fame brought him to the attention of Rhea, who was furious with Ammon for his deception. She attempted to bring Dionysus under her own power but, unable to do so, she left Ammon and married Cronus.

Zeus and Persephone

In the Orphic tradition, Dionysus was, in part, a associated with the underworld. As a result, the Orphics considered him the son of Persephone and Zeus, and believed that he had been dismembered by the Titans and then reborn. The myth of the dismemberment of Dionysus was alluded to as early as the 4th century BC by Plato in his Phaedo, in which Socrates claims that the initiations of the Dionysian Mysteries are similar to those of the philosophic path. Late Neoplatonists such as Damascius explored the implications of this at length. The dismemberment of Dionysus (the sparagmos) is often considered to be the most important myth of Orphism.

Many modern sources identify this "Orphic Dionysus" with the Zagreus, though this name does not seem to have been used by any of the ancient Orphics, who simply called him Dionysus. As pieced together from various ancient sources, the reconstructed story, usually given by modern scholars, goes as follows. Zeus had intercourse with Persephone in the form of a serpent, producing Dionysus. The infant was taken to Mount Ida, where, like the infant Zeus, he was guarded by the dancing Curetes. Zeus intended Dionysus to be his successor as ruler of the cosmos, but a jealous Hera incited the Titans to kill the child. It is said that he was mocked by the Titans who gave him a thyrsus (a fennel stalk) in place of his rightful scepter. Distracting the infant Dionysus with various toys, including a mirror, the Titans seized Dionysus and tore or cut him to pieces. The pieces were then boiled, roasted, and partially eaten by the Titans. But Athena managed to save Dionysus' heart, by which Zeus was able to contrive his rebirth from Semele.

In some traditions reported by the historian Diodorus Siculus, this "second Dionysus" was the son of Zeus and Demeter, the dess of agriculture, rather than Persephone. According to Diodorus, when the "Sons of Gaia" (i.e. the Titans) boiled Dionysus following his birth, Demeter gathered together his remains, allowing his second birth. Diodorus noted the symbolism this myth held for its adherents. Dionysus, of the vine, was born from the s of the rain and the earth. He was torn apart and boiled by the sons of Gaia, or "earth born", symbolizing the harvesting and wine-making process. Just as the remains of the bare vines are returned to the earth to restore its fruitfulness, the remains of the young Dionysus were returned to Demeter allowing him to be born again.

Zeus and Semele

The oldest sources, including Hesiod's Theogony and the Homeric Hymns (both written c. the 6th century BC), state that Dionysus was born to Zeus, the king of the s, and the mortal woman Semele, the daughter of Cadmus, king and founder of Thebes. In these accounts, Zeus' wife, Hera, discovered his affair while Semele was pregnant. Appearing as an old crone (or, in some versions, a nurse), Hera befriended Semele, who confided in her that Zeus was the father of the baby in her womb. Hera pretended not to believe her, and planted seeds of doubt in Semele's mind. Curious, Semele demanded of Zeus that he reveal himself in all his glory as proof of his hood. Though Zeus begged her not to ask this, she persisted, and he agreed. He came to her wreathed in bolts of lightning; mortals, however, could not look upon an undisguised without dying, and she perished in the ensuing blaze. Zeus rescued the unborn Dionysus, however, and after he sewed the infant into his thigh, Dionysus emerged fully-grown a few months later. In this version, Dionysus is borne by two "mothers" (Semele and Zeus) before his birth, hence the epithet dimētōr ("of two mothers") associated with his being "twice-born".

Other versions claim that Zeus recreated him in Semele's womb or that he impregnated Semele by giving her the heart to eat.

Infancy at Mount Nysa

According to the myth, Zeus gave the infant Dionysus to the care of Hermes. One version of the story is that Hermes took the boy to King Athamas and his wife Ino, Dionysus' aunt. Hermes bade the couple to raise the boy as a girl, to hide him from Hera's wrath. Another version is that Dionysus was taken to the rain-nymphs of Nysa, who nourished his infancy and childhood, and for their care Zeus rewarded them by placing them as the Hyades among the stars (see Hyades star cluster). Other versions have Zeus giving him to Rhea, or to Persephone to raise in the Underworld, away from Hera. Alternatively, he was raised by Maro. In yet another version of the myth, he is raised by his cousin Macris on the island of Euboea.

Dionysus in Greek mythology is a of foreign origin, and while Mount Nysa is a mythological location, it is invariably set far away to the east or to the south. The Homeric Hymn 1 to Dionysus places it "far from Phoenicia, near to the Egyptian stream". Others placed it in Anatolia, or in Libya ("away in the west beside a great ocean"), in Ethiopia (Herodotus), or Arabia (Diodorus Siculus).

According to Herodotus:

As it is, the Greek story has it that no sooner was Dionysus born than Zeus sewed him up in his thigh and carried him away to Nysa in Ethiopia beyond Egypt; and as for Pan, the Greeks do not know what became of him after his birth. It is therefore plain to me that the Greeks learned the names of these two s later than the names of all the others, and trace the birth of both to the time when they gained the knowledge.

— Herodotus, Histories 2.146.2

The Bibliotheca seems to be following Pherecydes, who relates how the infant Dionysus, of the grapevine, was nursed by the rain-nymphs, the Hyades at Nysa.

Childhood

When Dionysus grew up, he discovered the culture of the vine and the mode of extracting its precious juice, being the first to do so; but Hera struck him with madness, and drove him forth a wanderer through various parts of the earth. In Phrygia the dess Cybele, better known to the Greeks as Rhea, cured him and taught him her religious rites, and he set out on a progress through Asia teaching the people the cultivation of the vine. The most famous part of his wanderings is his expedition to India, which is said to have lasted several years. According to a legend, when Alexander the Great reached a city called Nysa near the Indus river, the locals said that their city was founded by Dionysus in the distant past and their city was dedicated to the Dionysus. These travels took something of the form of military conquests; according to Diodorus Siculus he conquered the whole world except for Britain and Ethiopia. Returning in triumph (he was considered the founder of the triumphal procession) he undertook to introduce his worship into Greece, but was opposed by some princes who dreaded its introduction on account of the disorders and madness it brought with it (e.g. Pentheus or Lycurgus).

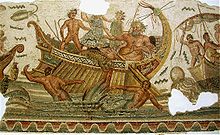

Dionysus was exceptionally attractive. The Homeric Hymn 7 to Dionysus recounts how, while disguised as a mortal sitting beside the seashore, a few sailors spotted him, believing he was a prince. They attempted to kidnap him and sail him far away to sell for ransom or into slavery. They tried to bind him with ropes, but no type of rope could hold him. Dionysus turned into a fierce lion and unleashed a bear on board, killing those he came into contact with. Those who jumped off the ship were mercifully turned into dolphins. The only survivor was the helmsman, Acoetes, who recognized the and tried to stop his sailors from the start.

In a similar story, Dionysus desired to sail from Icaria to Naxos. He then hired a Tyrrhenian pirate ship. However, when the was on board, they sailed not to Naxos but to Asia, intending to sell him as a slave. So Dionysus turned the mast and oars into snakes, and filled the vessel with ivy and the sound of flutes so that the sailors went mad and, leaping into the sea, were turned into dolphins. In Ovid's Metamorphoses, Bacchus begins this story as a young child, found by the pirates, but transforms to a divine adult when on board. Malcolm Bull notes that "It is a measure of Bacchus's ambiguous position in classical mythology that he, unlike the other Olympians, had to use a boat to travel to and from the islands with which he is associated".

Other myths

Midas

Dionysus discovered that his old school master and foster father, Silenus, had gone missing. The old man had been drinking, and had wandered away drunk, and was found by some peasants, who carried him to their king (alternatively, he passed out in Midas' rose garden). Midas recognized him, and treated him hospitably, entertaining him for ten days and nights with politeness, while Silenus entertained Midas and his friends with stories and songs. On the eleventh day, he brought Silenus back to Dionysus. Dionysus offered Midas his choice of whatever reward he wanted.

Midas asked that whatever he might touch should be changed into gold. Dionysus consented, though was sorry that he had not made a better choice. Midas rejoiced in his new power, which he hastened to put to the test. He touched and turned to gold an oak twig and a stone. Overjoyed, as soon as he got home, he ordered the servants to set a feast on the table. Then he found that his bread, meat, and wine turned to gold. Later, when his daughter embraced him, she too turned to gold.

Upset, Midas strove to divest himself of his power (the Midas Touch); he hated the gift he had coveted. He prayed to Dionysus, begging to be delivered from starvation. Dionysus heard and consented; he told Midas to wash in the river Pactolus. He did so, and when he touched the waters the power passed into them, and the river sands changed into gold. This was an etiological myth that explained why the sands of the Pactolus were rich in gold.

Pentheus

In the play The Bacchae by Euripides, Dionysus returns to his birthplace, Thebes, which is ruled by his cousin Pentheus. Pentheus, his mother Agave, and his aunts Ino and Autonoe do not believe that Dionysus is a son of Zeus. Despite the warnings of the blind prophet Tiresias, they deny him worship; instead, they arraign him for causing madness among the women of Thebes.

Dionysus uses his divine powers to drive Pentheus insane, then invites him to spy on the ecstatic rituals of the Maenads, in the woods of Mount Cithaeron. Pentheus, hoping to witness a sexual orgy, hides himself in a tree. The Maenads spot him; maddened by Dionysus, they take him to be a mountain-dwelling lion, and attack him with their bare hands. Pentheus' aunts, and his mother, Agave, are among them; they rip him limb from limb. Agave mounts his head on a pike, and takes the trophy to her father, Cadmus. The madness passes. Dionysus arrives in his true, divine form, banishes Agave and her sisters, and transforms Cadmus and his wife Harmonia into serpents. Only Tiresias is spared.

Lycurgus

When King Lycurgus of Thrace heard that Dionysus was in his kingdom, he imprisoned Dionysus' followers, the Maenads. Dionysus fled and took refuge with Thetis, and sent a drought which stirred the people into revolt. Dionysus then drove King Lycurgus insane and had him slice his own son into pieces with an axe in the belief that he was a patch of ivy, a plant holy to Dionysus. An oracle then claimed that the land would stay dry and barren as long as Lycurgus was alive. His people had him drawn and quartered. Following the death of the king, Dionysus lifted the curse. This story is told in Homer's epic, Iliad 6.136-7. In an alternative version, sometimes shown in art, Lycurgus tries to kill Ambrosia, a follower of Dionysus, who was transformed into a vine that twined around the enraged king and restrained him, eventually killing him.

Prosymnus

Dionysus descended to the underworld (Hades) to rescue his mother Semele, whom he had not seen since his birth, making the descent by way of a reputedly bottomless pool on the coast of the Argolid near the prehistoric site of Lerna, and bypassing Thanatos, the of death. According to Clement of Alexandria, Dionysus was guided by Prosymnus or Polymnus, who requested, as his reward, to be Dionysus' lover. Dionysus returned Semele to Mount Olympus; but Prosymnus died before Dionysus could honor his pledge, so in order to satisfy Prosymnus' shade, Dionysus fashioned a phallus from an olive branch and sat on it at Prosymnus' tomb. This story survives in full only in Christian sources whose aim was to discredit pagan mythology. It appears to have served to explain the secret objects of the Dionysian Mysteries.

Ampelus

Another myth according to Nonnus involves Ampelus, a satyr, who was loved by Dionysus. As related by Ovid, Ampelus became the constellation Vindemitor, or the "grape-gatherer":

...not so will the Grape-gatherer escape thee. The origin of that constellation also can be briefly told. 'Tis said that the unshorn Ampelus, son of a nymph and a satyr, was loved by Bacchus on the Ismarian hills. Upon him the bestowed a vine that trailed from an elm's leafy boughs, and still the vine takes from the boy its name. While he rashly culled the gaudy grapes upon a branch, he tumbled down; Liber bore the lost youth to the stars."

Another story of Ampelus was related by Nonnus: in an accident foreseen by Dionysus, the youth was killed while riding a bull maddened by the sting of a gadfly sent by Atë, the dess of Folly. The Fates granted Ampelus a second life as a vine, from which Dionysus squeezed the first wine.

Chiron

Young Dionysus was also said to have been one of the many famous pupils of the centaur Chiron. According to Ptolemy Chennus in the Library of Photius, "Dionysus was loved by Chiron, from whom he learned chants and dances, the bacchic rites and initiations."

Secondary myths

When Hephaestus bound Hera to a magical chair, Dionysus got him drunk and brought him back to Olympus after he passed out.

When Theseus abandoned Ariadne sleeping on Naxos, Dionysus found and married her. She bore him a son named Oenopion, but he committed suicide or was killed by Perseus. In some variants, he had her crown put into the heavens as the constellation Corona; in others, he descended into Hades to restore her to the s on Olympus. Another different account claims Dionysus ordered Theseus to abandon Ariadne on the island of Naxos for he had seen her as Theseus carried her onto the ship and had decided to marry her.

A third descent by Dionysus to Hades is invented by Aristophanes in his comedy The Frogs. Dionysus, as patron of the Athenian dramatic festival, the Dionysia, wants to bring back to life one of the great tragedians. After a competition Aeschylus is chosen in preference to Euripides.

Psalacantha, a nymph, failed at winning the love of Dionysus as his main love interest at the moment was Ariadne, and ended up being changed into a plant.

Callirrhoe was a Calydonian woman who scorned Coresus, a priest of Dionysus, who threatened to afflict all the women of Calydon with insanity (see Maenad). The priest was ordered to sacrifice Callirhoe but he killed himself instead. Callirhoe threw herself into a well which was later named after her.

Lovers and children

| Consort | Offspring | Consort | Offspring |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aphrodite | • Hymenaios | Alexirrhoe | • Carmanor |

| • Iacchus | Alphesiboea | • Medus | |

| • Priapus | • Phthonus | ||

| • Charites (Graces) | Althaea | • Deianira | |

| 1. Euphrosyne | Araethyrea | • Phlias | |

| 2. Pasithea | Chthonophyle | ||

| 3. Thalia | Carya | no known offspring | |

| Ariadne | • Ceramus | Chione | • Priapus (possibly) |

| • Euanthes | Circe | • Comus | |

| • Eurymedon | Cronois | • Charites (Graces) | |

| • Latramys | 1. Euphrosyne | ||

| • Maron | 2. Pasithea | ||

| • Oenopion | 3. Thalia | ||

| • Phanus | Nicaea | • Telete | |

| • Peparethus | Pallene | no known offspring | |

| • Phlias | Percote | • Priapus (possibly) | |

| • Staphylus | Physcoa | • Narcaeus | |

| • Tauropolis | Unnamed woman | • Methe | |

| • Thoas | Unnamed woman | • Sabazios | |

| Aura | • Iacchus | Unnamed woman | • Thysa |

| • twin of Iacchus |

In the arts

Classical art

The , and still more often his followers, were commonly depicted in the painted pottery of Ancient Greece, much of which was vessels for wine. But, apart from some reliefs of maenads, Dionysian subjects rarely appeared in large sculpture before the Hellenistic period, when they became common. In these, the treatment of the himself ranged from severe archaising or Neo Attic types such as the Dionysus Sardanapalus to types showing him as an indolent and androgynous young man, often nude. Hermes and the Infant Dionysus is probably a Greek original in marble, and the Ludovisi Dionysus group is probably a Roman original of the 2nd century AD. Well-known Hellenistic sculptures of Dionysian subjects, surviving in Roman copies, include the Barberini Faun, the Belvedere Torso, the Resting Satyr. The Furietti Centaurs and Sleeping Hermaphroditus reflect related subjects, which had by this time become drawn into the Dionysian orbit. The marble Dancer of Pergamon is an original, as is the bronze Dancing Satyr of Mazara del Vallo, a recent recovery from the sea.

The Dionysian world by the Hellenistic period is a hedonistic but safe pastoral into which other semi-divine creatures of the countryside such as centaurs, nymphs, and the Pan and Hermaphrodite have been co-opted. Nymphs by this stage "means simply an ideal female of the Dionysian outdoors, a non-wild bacchant". Hellenistic sculpture also includes for the first time large genre subjects of children and peasant, many of whom carry Dionysian attributes such as ivy wreaths, and "most should be seen as part of his realm. They have in common with satyrs and nymphs that they are creatures of the outdoors and are without true personal identity." The 4th-century BC Derveni Krater, the unique survival of a very large scale Classical or Hellenistic metal vessel of top quality, depicts Dionysus and his followers.

Dionysus appealed to the Hellenistic monarchies for a number of reasons, apart from merely being a of pleasure: He was a human who became divine, he came from, and had conquered, the East, exemplified a lifestyle of display and magnificence with his mortal followers, and was often regarded as an ancestor. He continued to appeal to the rich of Imperial Rome, who populated their gardens with Dionysian sculpture, and by the 2nd century AD were often buried in sarcophagi carved with crowded scenes of Bacchus and his entourage.

The 4th-century AD Lycurgus Cup in the British Museum is a spectacular cage cup which changes colour when light comes through the glass; it shows the bound King Lycurgus being taunted by the and attacked by a satyr; this may have been used for celebration of Dionysian mysteries. Elizabeth Kessler has theorized that a mosaic appearing on the triclinium floor of the House of Aion in Nea Paphos, Cyprus, details a monotheistic worship of Dionysus. In the mosaic, other s appear but may only be lesser representations of the centrally imposed Dionysus. The mid-Byzantine Veroli Casket shows the tradition lingering in Constantinople around 1000 AD, but probably not very well understood.

Art from the Renaissance on

Bacchic subjects in art resumed in the Italian Renaissance, and soon became almost as popular as in antiquity, but his "strong association with feminine spirituality and power almost disappeared", as did "the idea that the destructive and creative powers of the were indissolubly linked". In Michelangelo's statue (1496–97) "madness has become merriment". The statue aspires to suggest both drunken incapacity and an elevated consciousness, but this was perhaps lost on later viewers, and typically the two aspects were thereafter split, with a clearly drunk Silenus representing the former, and a youthful Bacchus often shown with wings, because he carries the mind to higher places.

Titian's Bacchus and Ariadne (1522–23) and The Bacchanal of the Andrians (1523–26), both painted for the same room, offer an influential heroic pastoral, while Diego Velázquez in The Triumph of Bacchus (or Los borrachos – "the drinkers", c. 1629) and Jusepe de Ribera in his Drunken Silenus choose a genre realism. Flemish Baroque painting frequently painted the Bacchic followers, as in Van Dyck's Drunken Silenus and many works by Rubens; Poussin was another regular painter of Bacchic scenes.

A common theme in art beginning in the 16th century was the depiction of Bacchus and Ceres caring for a representation of love – often Venus, Cupid, or Amore. This tradition derived from a quotation by the Roman comedian Terence (c. 195/185 – c. 159 BC) which became a popular proverb in the Early Modern period: Sine Cerere et Baccho friget Venus ("without Ceres and Bacchus, Venus freezes"). Its simplest level of meaning is that love needs food and wine to thrive. Artwork based on this saying was popular during the period 1550–1630, especially in Northern Mannerism in Prague and the Low Countries, as well as by Rubens. Because of his association with the vine harvest, Bacchus became the of autumn, and he and his followers were often shown in sets depicting the seasons.

Modern literature and philosophy

Dionysus has remained an inspiration to artists, philosophers and writers into the modern era. In The Birth of Tragedy (1872), the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche proposed that a tension between Apollonian and Dionysian aesthetic principles underlay the development of Greek tragedy; Dionysus represented what was unrestrained chaotic and irrational, while Apollo represented the rational and ordered. Nietzsche claimed that the oldest forms of Greek Tragedy were entirely based on suffering of Dionysus. In Nietzsche's 1886 work Beyond Good and Evil, and later works The Twilight of the Idols, The Antichrist and Ecce Homo, Dionysus is conceived as the embodiment of the unrestrained will to power.

In The Hellenic Religion of the Suffering (1904), and Dionysus and Early Dionysianism (1921), the poet Vyacheslav Ivanov elaborates the theory of Dionysianism, tracing the origins of literature, and tragedy in particular, to ancient Dionysian mysteries. Karl Kerényi characterizes Dionysus as representative of the psychological life force (Greek Zoê). Other psychological interpretations place Dionysus' emotionality in the foreground, focusing on the joy, terror or hysteria associated with the . Sigmund Freud specified that his ashes should be kept in an Ancient Greek vase painted with Dionysian scenes from his collection, which remains on display at Golders Green Crematorium in London.

In CS Lewis' Prince Caspian (part of The Chronicles of Narnia), Bacchus is a dangerous-looking, androgynous young boy who helps Aslan awaken the spirits of the Narnian trees and rivers. Rick Riordan's series of books Percy Jackson & The Olympians presents Dionysus as an uncaring, childish and spoiled . In the novel Household s by Harry Turtledove and Judith Tarr, Nicole Gunther-Perrin is a lawyer in the 20th century. She makes a libation to Liber and Libera, Roman equivalents of Dionysus and Persephone, and is transported back in time to ancient Rome. In The Secret History by Donna Tartt, a group of classics students reflect on reviving the worship of Dionysus during their time in college.

Modern film and performance art

Walt Disney depicted Bacchus in the "Pastoral" segment of the animated film Fantasia, as a Silenus-like character. In 1969, an adaption of The Bacchae was performed, called Dionysus in '69. A film was made of the same performance. The production was notable for involving audience participation, nudity, and theatrical innovations. In 1974, Stephen Sondheim and Burt Shevelove adapted Aristophanes' comedy The Frogs into a modern musical, which hit broadway in 2004 and was revived in London in 2017. The musical keeps the descent of Dionysus into Hades to bring back a playwright; however, the playwrights are updated to modern times, and Dionysus is forced to choose between George Bernard Shaw and William Shakespeare.

In 2018, the Australian musical project Dead Can Dance released an album entitled Dionysus. Musician Brendan Perry described the inspiration for the album as a trance-like, "Dionysian" experience he had at a festival during a trip to rural Spain. "It's the spring festivals like that one where you see the real remnants of Dionysian festivals. They're all over the Mediterranean in remote places where Christian influence hasn't been as great. ... People wear masks and dance in circles almost like time has stood still in their celebrations." Perry chose to employ Mediterranean folk instruments that mimic natural sounds in addition to a vocal chorus, in order to evoke the atmosphere of an ancient festival.

Parallels with Christianity

Main article: Jesus Christ in comparative mythology

Numerous scholars have compared narratives surrounding the Christian figure of Jesus with those associated with Dionysus.

Death and Resurrection

Some scholars of comparative mythology identify both Dionysus and Jesus with the dying-and-returning mythological archetype. On the other hand, it has been noted that the details of Dionysus' death and rebirth are starkly different both in content and symbolism from Jesus. The two stories take place in very different historical and geographic contexts. Also, the manner of death is different; in the most common myth, Dionysus was torn to pieces and eaten by the titans, but "eventually restored to a new life" from the heart that was left over.

Trial

Another parallel can be seen in The Bacchae where Dionysus appears before King Pentheus on charges of claiming divinity, which is compared to the New Testament scene of Jesus being interrogated by Pontius Pilate. However, a number of scholars dispute this parallel, since the confrontation between Dionysus and Pentheus ends with Pentheus dying, torn into pieces by the mad women, whereas the trial of Jesus ends with him being sentenced to death. The discrepancies between the two stories, including their resolutions, have led many scholars to regard the Dionysus story as radically different from the one about Jesus, except for the parallel of the arrest, which is a detail that appears in many biographies as well.

Sacred Food and Drink

Other elements, such as the celebration by a ritual meal of bread and wine, also have parallels. The omophagia was the Dionysian act of eating raw flesh and drinking wine to consume the . Within Orphism, it was believed that consuming the meat and wine was symbolic of the Titans eating the flesh (meat) and blood (wine) of Dionysus and that, by participating in the omophagia, Dionysus' followers could achieve communion with the . Powell, in particular, argues that precursors to the Catholic notion of transubstantiation can be found in Dionysian religion.

Other parallels

E. Kessler has argued that the Dionysian cult developed into strict monotheism by the 4th century AD; together with Mithraism and other sects, the cult formed an instance of "pagan monotheism" in direct competition with Early Christianity during Late Antiquity. Scholars from the 16th century onwards, especially Gerard Vossius, also discussed the parallels between the biographies of Dionysus/Bacchus and Moses (Vossius named his sons Dionysius and Isaac). Such comparisons surface in details of paintings by Poussin.

Tacitus, John the Lydian, and Cornelius Labeo all identify Yahweh with the Greek Dionysus. Jews themselves frequently used symbols that were also associated with Dionysus such as kylixes, amphorae, leaves of ivy, and clusters of grapes. In his Quaestiones Convivales, the Greek writer Plutarch of Chaeronea writes that the Jews hail their with cries of "Euoi" and "Sabi", phrases associated with the worship of Dionysus. According to Sean M. McDonough, Greek-speakers may have confused Aramaic words such as Sabbath, Alleluia, or even possibly some variant of the name Yahweh itself for more familiar terms associated with Dionysus.

Genealogy

| Dionysus' family tree | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Gallery

-

Roman marble sarcophagus with the Triumph of Dionysos and the Seasons (circa 260–270 AD)

Roman marble sarcophagus with the Triumph of Dionysos and the Seasons (circa 260–270 AD)

-

Triumph of Dionysus

Triumph of Dionysus

-

The Dionysus Cup, a 6th-century BC kylix with Dionysus sailing with the pirates he transformed to dolphins

The Dionysus Cup, a 6th-century BC kylix with Dionysus sailing with the pirates he transformed to dolphins

-

Dionysos riding a cheetah, Macedonian mosaic from Pella, Greece (4th century BC)

Dionysos riding a cheetah, Macedonian mosaic from Pella, Greece (4th century BC)

-

Statue of Dionysus (Sardanapalus) (Museo Palazzo Massimo Alle Terme, Rome)

Statue of Dionysus (Sardanapalus) (Museo Palazzo Massimo Alle Terme, Rome)

-

Bronze head of Dionysus (50 BC - 50 AD) in the British Museum

-

Statue of Dionysus in Remich Luxembourg

-

A Bacchus themed table - the top was made in Florence (c. 1736) and the gilded wood base in Britain or Ireland (circa 1736–1740).

A Bacchus themed table - the top was made in Florence (c. 1736) and the gilded wood base in Britain or Ireland (circa 1736–1740).

-

Bacchus - Hendrick Goltzius (1592)

Bacchus - Hendrick Goltzius (1592)

-

Dionysian amphora

Dionysian amphora

-

Dionysian jug

Dionysian jug

-

Terracotta vase in the shape of Dionysus' head (circa 410 BC) - on display in the Ancient Agora Museum in Athens, housed in the Stoa of Attalus

Terracotta vase in the shape of Dionysus' head (circa 410 BC) - on display in the Ancient Agora Museum in Athens, housed in the Stoa of Attalus

-

A mosaic of Dionysus from Antioch

A mosaic of Dionysus from Antioch

See also

Notes

- Hedreen, Guy Michael. Silens in Attic Black-figure Vase-painting: Myth and Performance. University of Michigan Press. 1992. ISBN 9780472102952. page 1

- James, Edwin Oliver. The Tree of Life: An Archaeological Study. Brill Publications. 1966. page 234. ISBN 9789004016125

- Gately, Iain (2008). Drink. Gotham Books. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-592-40464-3.

- Ferguson, Everett (2003). Backgrounds of Early Christianity. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 9780802822215.

- He appears as a likely theonym (divine name) in Linear B tablets as di-wo-nu-so (KH Gq 5 inscription)

- ^ Raymoure, K.A. (November 2, 2012). "Khania Linear B Transliterations". Minoan Linear A & Mycenaean Linear B. Deaditerranean. "Possible evidence of human sacrifice at Minoan Chania". Archaeology News Network. 2014. Raymoure, K.A. "Khania KH Gq Linear B Series". Minoan Linear A & Mycenaean Linear B. Deaditerranean. "KH 5 Gq (1)". DĀMOS: Database of Mycenaean at Oslo. University of Oslo.

- Kerényi 1976.

- Thomas McEvilley, The Shape of Ancient Thought, Allsworth press, 2002, pp. 118–121. Google Books preview

- Reginald Pepys Winnington-Ingram, Sophocles: an interpretation, Cambridge University Press, 1980, p.109 Google Books preview

- Zofia H. Archibald, in Gocha R. Tsetskhladze (Ed.) Ancient Greeks west and east, Brill, 1999, p.429 ff.Google Books preview

- Sutton, p.2, mentions Dionysus as The Liberator in relation to the city Dionysia festivals. In Euripides, Bacchae 379–385: "He holds this office, to join in dances, to laugh with the flute, and to bring an end to cares, whenever the delight of the grape comes at the feasts of the s, and in ivy-bearing banquets the goblet sheds sleep over men."

- John Chadwick, The Mycenaean World, Cambridge University Press, 1976, 99ff: "But Dionysos surprisingly appears twice at Pylos, in the form Diwonusos, both times irritatingly enough on fragments, so that we have no means of verifying his divinity."

- "The Linear B word di-wo-nu-so". Palaeolexicon. Word study tool of ancient languages.

- This is the view of Garcia Ramon (1987) and Peters (1989), summarised and endorsed in Janda (2010:20).

- Fox, p. 217, "The word Dionysos is divisible into two parts, the first originally Διος (cf. Ζευς), while the second is of an unknown signification, although perhaps connected with the name of the Mount Nysa which figures in the story of Lykourgos: (...) when Dionysos had been reborn from the thigh of Zeus, Hermes entrusted him to the nymphs of Mount Nysa, who fed him on the food of the s, and made him immortal."

- Testimonia of Pherecydes in an early 5th-century BC fragment, FGrH 3, 178, in the context of a discussion on the name of Dionysus: "Nũsas (acc. pl.), he said, was what they called the trees."

- ^ Nonnus, Dionysiaca 9.20–24.

- Suda s.v. Διόνυσος .

- R. S. P. Beekes, Etymological Dictionary of Greek, Brill, 2009, p. 337.

- see Janda (2010), 16–44 for a detailed account.

- Otto, Walter F. (1995). Dionysus Myth and Cult. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-20891-2.

- Daniélou, Alain (1992). s of Love and Ecstasy. Rochester, Vermont: Inner Traditions. p. 15. ISBN 9780892813742.

- Pausanias, 8.39.6.

- Stephanus of Byzantium, s.v. Ακρωρεία

- Used thus by Ausonius, Epigrams, 29, 6, and in Catullus, 29; see Lee M. Fratantuono, NIVALES SOCII: CAESAR, MAMURRA, AND THE SNOW OF CATULLUS C. 57, Quaderni Urbinati di Cultura Classica, New Series, Vol. 96, No. 3 (2010), p. 107, Note 2.

- Smith, s.v. Aegobolus; Pausanias, 9.8.1–2.

- Erwin Rohde, Psyché, p. 269

- Aristid.Or.41

- Macr.Sat.I.18.9

- For a parallel see pneuma/psuche/anima The core meaning is wind as "breath/spirit"

- Bulls in antiquity were said to roar.

- Blackwell, Christopher W.; Blackwell, Amy Hackney (2011-03-21). Mythology For Dummies. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781118053874.

- McKeown, J.C. A Cabinet of Greek Curiosities: Strange Tales and Surprising Facts from the Cradle of Western Civilization, Oxford University Press, New York, 2013, p. 210)

- Clement of Alexandria, Exhortation to the Greeks, 92: 82–83, Loeb Classical Library (registration required: accessed 17 December 2016)

- Kerényi 1967; Kerényi 1976.

- Janda (2010), 16–44.

- Kerényi 1976, p. 286.

- Jameson 1993, 53. Cf.n16 for suggestions of Devereux on "Enorkhes,"

- http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/morph?l=%CE%BB%CF%85%CE%B1%CE%B9%CE%BF%CF%82&la=greek#lexicon Liddell-Scott-Jones Greek-English Lexicon

- Liddell-Scott-Jones Greek-English Lexicon

- Mentioned by Erasmus in The Praise of Folly

- Diodorus Siculus, 4.4.1.

- Diodorus Siculus, 4.4.5.

- Diodorus Siculus, 4.5.2.

- ^ Diodorus Siculus 3.62–74.

- Damascius, Commentary on the Phaedo, I, 1–13 and 165–172, see in translation Westerink, The Greek Commentaries on Plato's Phaedo, vol. II, The Prometheus Trust, Westbury, 2009

- Nilsson, p. 202 calls it "the cardinal myth of Orphism"; Guthrie, p. 107, describes the myth as "the central point of Orphic story", Linforth, p. 307 says it is "commonly regarded as essentially and peculiarly Orphic and the very core of the Orphic religion", and Parker 2002, p. 495, writes that "it has been seen as the Orphic 'arch-myth'.

- According to Gantz, p. 118, 'Orphic sources preserved seem not to use the name "Zagreus", and according to West 1983, p. 153, the 'name was probably not used in the Orphic narrative'. Edmonds 1999, p. 37 n. 6 says: 'Lobeck 1892 seems to be responsible for the use of the name Zagreus for the Orphic Dionysos. As Linforth noticed, "It is a curious thing that the name Zagreus does not appear in any Orphic poem or fragment, nor is it used by any author who refers to Orpheus" (Linforth 1941:311). In his reconstruction of the story, however, Lobeck made extensive use of the fifth-century CE epic of Nonnos, who does use the name Zagreus, and later scholars followed his cue. The association of Dionysos with Zagreus appears first explicitly in a fragment of Callimachus preserved in the Etymologicum Magnum (fr. 43.117 P), with a possible earlier precedent in the fragment from Euripides Cretans (fr. 472 Nauck). Earlier evidence, however, (e.g., Alkmaionis fr. 3 PEG; Aeschylus frr. 5, 228) suggests that Zagreus was often identified with other .'

- West 1983, pp. 73–74, provides a detailed reconstruction with numerous cites to ancient sources, with a summary on p. 140. For other summaries see Morford, p. 311; Hard, p. 35; Marsh, s.v. Zagreus, p. 788; Grimal, s.v. Zagreus, p. 456; Burkert, pp. 297–298; Guthrie, p. 82; also see Ogden, p. 80. For a detailed examination of many of the ancient sources pertaining to this myth see Linforth, pp. 307–364. The most extensive account in ancient sources is found in Nonnus, Dionysiaca 5.562–70, 6.155 ff., other principle sources include Diodorus Siculus, 3.62.6–8 (= Orphic fr. 301 Kern), 3.64.1–2, 4.4.1–2, 5.75.4 (= Orphic fr. 303 Kern); Ovid, Metamorphoses 6.110–114; Athenagoras of Athens, Legatio 20 Pratten (= Orphic fr. 58 Kern); Clement of Alexandria, Protrepticus 2.15 pp. 36–39 Butterworth (= Orphic frs. 34, 35 Kern); Hyginus, Fabulae 155, 167; Suda s.v. Ζαγρεύς. See also Pausanias, 7.18.4, 8.37.5.

- Damascius, Commentary on the Phaedo, I, 170, see in translation Westerink, The Greek Commentaries on Plato's Phaedo, vol. II (The Prometheus Trust, Westbury) 2009

- Diodorus Siculus, 5.75.4, noted by Kerényi 1976, "The Cretan core of the Dionysos myth" p. 111 n. 213 and pp. 110–114.

- Diodorus Siculus 3.64.1; also noted by Kerény (110 note 214).

- Apollodorus, The Library, with an English Translation by Sir James George Frazer, F.B.A., F.R.S. in 2 Volumes. Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1921. Includes Frazer's notes. ISBN 0-674-99135-4, ISBN 0-674-99136-2

- Conner, Nancy. "The Everything Book of Classical Mythology" 2ed

- Bull, 255

- Arrian, Anabasis of Alexander 5.1.1–2.2

- Bull, 253

- "Theoi.com" Homeric Hymn to Dionysus". Theoi.com. Retrieved 2014-06-29.

- Bull, 245–247, 247 quoted

- Euripides, Bacchae.

- "British Museum – The Lycurgus Cup". britishmuseum.org.

- Varadpande, M. L. (1981). Ancient Indian And Indo-Greek Theatre. Abhinav Publications. p. 91-93. ISBN 9788170171478.

- Clement of Alexandria, Protreptikos, II-30 3–5

- Arnobius, Adversus Gentes 5.28 (pp. 252–253) (Dalby 2005, pp. 108–117)

- Ovid, Fasti, iii. 407 ff. (James G. Frazer, translator).

- Nonnus, Dionysiaca 10.175–430, 11, 12.1–117 (Dalby 2005, pp. 55–62).

- Photius, Library; "Ptolemy Chennus, New History"

- Scholia on Theocritus, Idyll 1. 21

- Hesychius of Alexandria s. v. Priēpidos

- Strabo, 10.3.13, quotes the non-extant play Palamedes which seems to refer to Thysa, a daughter of Dionysus, and her (?) mother as participants of the Bacchic rites on Mount Ida, but the quoted passage is corrupt.

- unnamed brother of Iacchus who was killed by Aura instantly upon birth

- Smith 1991, 127–129

- as in the Dionysus and Eros, Naples Archeological Museum

- Smith 1991, 127–154

- Smith 1991, 127, 131, 133

- Smith 1991, 130

- Smith 1991, 136

- Smith 1991, 127

- Smith 1991, 128

- Kessler, E., Dionysian Monotheism in Nea Paphos, Cyprus,

- Bull, 227–228, both quoted

- Bull, 228–232, 228 quoted

- Bull, 235–238, 242, 247–250

- Bull, 233–235

- Malcolm Bull, The Mirror of the s, How Renaissance Artists Rediscovered the Pagan s, Oxford UP, 2005, ISBN 978-0195219234

- Kerenyi, K., Dionysus: Archetypal Image of Indestructible Life (Princeton/Bollingen, 1976).

- Jeanmaire, H. Dionysus: histoire du culte de Bacchus, (p.106ff) Payot, (1951)

- Johnson, R. A. 'Ecstasy; Understanding the Psychology of Joy' HarperColling (1987)

- Hillman, J. 'Dionysus Reimagined' in The Myth of Analysis (pp.271–281) HarperCollins (1972); Hillman, J. 'Dionysus in Jung's Writings' in Facing The s, Spring Publications (1980)

- Thompson, J. 'Emotional Intelligence/Imaginal Intelligence' in Mythopoetry Scholar Journal, Vol 1, 2010

- Lopez-Pedraza, R. 'Dionysus in Exile: On the Repression of the Body and Emotion', Chiron Publications (2000)

- Johnson, Sarah. "Household s". Historical Novel Society. Historical Novel Society. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- Horton, Rich. "Household s". SF Site. SF Site. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- Kakutani, Michiko. "Books of The Times; Students Indulging in Course of Destruction". The New York Times. The New York Times. Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- Greenspun, Roger (March 23, 1970). "Screen::De Palma's 'Dionysus in 69'". New York Times. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- Murray, Matthew. "The Frogs". Talkin' Broadway. Talkin' Broadway. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- Grow, Kory. "Dead Can Dance on Awakening the Ancient Instincts Within" Rolling Stone, NOVEMBER 7, 2018.

- Detienne, Marcel. Dionysus Slain. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins, 1979.

- Evans, Arthur. The of Ecstasy. New York: St. Martins' Press, 1989

- Wick, Peter (2004). "Jesus gegen Dionysos? Ein Beitrag zur Kontextualisierung des Johannesevangeliums". Biblica. 85 (2). Rome: Pontifical Biblical Institute: 179–198. Retrieved 2007-10-10.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Powell, Barry B., Classical Myth. Second ed. With new translations of ancient texts by Herbert M. Howe. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1998.

- Studies in Early Christology, by Martin Hengel, 2005, p. 331 (ISBN 0567042804).

- Dalby, Andrew (2005). The Story of Bacchus. London: British Museum Press.

- E. Kessler, Dionysian Monotheism in Nea Paphos, Cyprus. Symposium on Pagan Monotheism in the Roman Empire, Exeter, 17–20 July 2006 Abstract Archived 2008-04-21 at the Wayback Machine)

- Bull, 240–241

- McDonough 1999, p. 88.

- Smith & Cohen 1996a, p. 233. sfn error: no target: CITEREFSmithCohen1996a (help)

- Plutarch, Quaestiones Convivales, Question VI

- McDonough 1999, p. 89.

- Smith & Cohen 1996a, pp. 232–233. sfn error: no target: CITEREFSmithCohen1996a (help)

- McDonough 1999, pp. 89–90.

- According to Homer, Aphrodite was the daughter of Zeus (Iliad 3.374, 20.105; Odyssey 8.308, 320) and Dione (Iliad 5.370–71), see Gantz, pp. 99–100.

- According to Homer, Iliad 1.570–579, 14.338, Odyssey 8.312, Hephaestus was apparently the son of Hera and Zeus, see Gantz, p. 74.

- According to Hesiod's Theogony 886–890, of Zeus' children by his seven wives, Athena was the first to be conceived, but the last to be born; Zeus impregnated Metis then swallowed her, later Zeus himself gave birth to Athena "from his head", see Gantz, pp. 51–52, 83–84.

- According to Hesiod, Theogony 183–200, Aphrodite was born from Uranus' severed genitals, see Gantz, pp. 99–100.

- According to Hesiod, Theogony 927–929, Hephaestus was produced by Hera alone, with no father, see Gantz, p. 74.

- "British Museum - statue". British Museum.

References

- Aristides, Aristides ex recensione Guilielmi Dindorfii, Volume 3, Wilhelm Dindorf, Weidmann, G. Reimer, 1829. Hathi Trust Digital Library.

- Aristophanes, Frogs, Matthew Dillon, Ed., Perseus Digital Library, Tufts University, 1995. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Arnobius of Sicca, The Seven Books of Arnobius Adversus Gentes, translated by Archibald Hamilton Bryce and Hugh Campbell, Edinburg: T. & T. Clark. 1871. Internet Archive.

- Arrian, Anabasis of Alexander, Volume I: Books 1–4, translated by P. A. Brunt. Loeb Classical Library No. 236. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1976. ISBN 978-0-674-99260-3. Online version at Harvard University Press.

- Arrian, Anabasis of Alexander, Volume II: Books 5–7, translated by P. A. Brunt. Loeb Classical Library No. 269. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1976. ISBN 978-0-674-99297-9. Online version at Harvard University Press.

- Bowie, A. M., Aristophanes: Myth, Ritual and Comedy, Cambridge University Press, 1993. ISBN 0521440122.

- Bowie, E. L., "Time and Place, Narrative and Speech in Philicus, Philodams and Limenius" in Hymnic Narrative and the Narratology of Greek Hymns, edited by Andrew Faulkner, Owen Hodkinson, BRILL, 2015. ISBN 9789004289512.

- Bull, Malcolm, The Mirror of the s, How Renaissance Artists Rediscovered the Pagan s, Oxford UP, 2005, ISBN 9780195219234

- Burkert, Walter, Greek Religion, Harvard University Press, 1985. ISBN 0-674-36281-0.

- Clement of Alexandria, The Exhortation to the Greeks. The Rich Man's Salvation. To the Newly Baptized. Translated by G. W. Butterworth. Loeb Classical Library No. 92. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1919. ISBN 978-0-674-99103-3. Online version at Harvard University Press. Internet Archive 1960 edition.

- Collard, Christopher and Martin Cropp, Euripides Fragments: Oedipus-Chrysippus: Other Fragments, Loeb Classical Library No. 506. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2008. ISBN 978-0-674-99631-1. Online version at Harvard University Press.

- Dalby, Andrew (2005). The Story of Bacchus. London: British Museum Press. ISBN 0-7141-2255-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Diodorus Siculus, Diodorus Siculus: The Library of History. Translated by C. H. Oldfather. Twelve volumes. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press; London: William Heinemann, Ltd. 1989. Online version by Bill Thayer

- Edmonds, Radcliffe (1999), "Tearing Apart the Zagreus Myth: A Few Disparaging Remarks On Orphism and Original Sin", Classical Antiquity 18 (1999): 35–73. PDF.

- Encinas Reguero, M. Carmen, "The Names of Dionysos in Euripides’ Bacchae and the Rhetorical Language of Teiresias", in Redefining Dionysos, Editors: Alberto Bernabé, Miguel Herrero de Jáuregui, Ana Isabel Jiménez San Cristóbal, Raquel Martín Hernández. Walter de Gruyter, 2013. ISBN 978-3-11-030091-8.

- Euripides, Bacchae, translated by T. A. Buckley in The Tragedies of Euripides, London. Henry G. Bohn. 1850. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Euripides, Cyclops, in Euripides, with an English translation by David Kovacs, Cambridge. Harvard University Press. forthcoming. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Euripides, Ion, translated by Robert Potter in The Complete Greek Drama, edited by Whitney J. Oates and Eugene O'Neill, Jr. Volume 1. New York. Random House. 1938. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Euripides, The Trojan Women, in The Plays of Euripides, translated by E. P. Coleridge. Volume I. London. George Bell and Sons. 1891. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Fantuzzi, Marco, "Sung Poetry: The Case of Inscribed Paeans" in A Companion to Hellenistic Literature, editors: James J. Clauss, Martine Cuypers, John Wiley & Sons, 2010. ISBN 9781405136792.

- Farnell, Lewis Richard, The Cults of the Greek States vol 5, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1909 Internet Archive; cf. Chapter IV, "Cults of Dionysos"; Chapter V, "Dionysiac Ritual"; Chapter VI, "Cult-Monuments of Dionysos"; Chapter VII, "Ideal Dionysiac Types".

- Lightfoot, J. L. Hellenistic Collection: Philitas. Alexander of Aetolia. Hermesianax. Euphorion. Parthenius. Edited and translated by J. L. Lightfoot. Loeb Classical Library No. 508. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2010. ISBN 978-0-674-99636-6. Online version at Harvard University Press.

- Fox, William Sherwood, The Mythology of All Races, v.1, Greek and Roman, 1916, General editor, Louis Herbert Gray.

- Gantz, Timothy, Early Greek Myth: A Guide to Literary and Artistic Sources, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996, Two volumes: ISBN 978-0-8018-5360-9 (Vol. 1), ISBN 978-0-8018-5362-3 (Vol. 2).

- Graf, F. (1974), Eleusis und die orphische Dichtung Athens in vorhellenistischer Zeit, Walter de Gruyter, 1974. ISBN 9783110044980.

- Graf, F. (2005), "Iacchus" in Brill's New Pauly: Encyclopaedia of the Ancient World. Antiquity, Volume 6, Lieden-Boston 2005.

- Grimal, Pierre, The Dictionary of Classical Mythology, Wiley-Blackwell, 1996, ISBN 978-0-631-20102-1.

- Guthrie, W. K. C., Orpheus and Greek Religion: A Study of the Orphic Movement, Princeton University Press, 1935. ISBN 978-0-691-02499-8.

- Hard, Robin, The Routledge Handbook of Greek Mythology: Based on H.J. Rose's "Handbook of Greek Mythology", Psychology Press, 2004, ISBN 978-0-415-18636-0.

- Harder, Annette, Callimachus: Aetia: Introduction, Text, Translation and Commentary, Oxford University Press, 2012. ISBN 978-0-19-958101-6. (two volume set). Google Books

- Harrison, Jane Ellen, Prolegomena to the Study of Greek Religion, second edition, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1908. Internet Archive

- Herodotus; Histories, A. D. ley (translator), Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1920; ISBN 0674991338. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Hesiod, Theogony, in The Homeric Hymns and Homerica with an English Translation by Hugh G. Evelyn-White, Cambridge, Massachusetts., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1914. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Homer, The Iliad with an English Translation by A.T. Murray, PhD in two volumes. Cambridge, Massachusetts., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann, Ltd. 1924. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Homer; The Odyssey with an English Translation by A.T. Murray, PH.D. in two volumes. Cambridge, Massachusetts., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann, Ltd. 1919. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Hyginus, Gaius Julius, Fabulae in Apollodorus' Library and Hyginus' Fabuae: Two Handbooks of Greek Mythology, Translated, with Introductions by R. Scott Smith and Stephen M. Trzaskoma, Hackett Publishing Company, 2007. ISBN 978-0-87220-821-6.

- Janda, Michael, Die Musik nach dem Chaos, Innsbruck 2010.

- Jameson, Michael. "The Asexuality of Dionysus." Masks of Dionysus. Ed. Thomas H. Carpenter and Christopher A. Faraone. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 1993. ISBN 0-8014-8062-0. 44–64.

- Jiménez San Cristóbal, Anna Isabel, 2012, "Iacchus in Plutarch" in Plutarch in the Religious and Philosophical Discourse of Late Antiquity, edited by Fernando Lautaro Roig Lanzillotta and Israel Mu Oz Gallarte, Brill, ISBN 9789004234741.

- Jiménez San Cristóbal, Anna Isabel 2013, "The Sophoclean Dionysos" in Redefining Dionysus, Editors: Alberto Bernabé, Miguel Herrero de Jáuregui, Ana Isabel Jiménez San Cristóbal, Raquel Martín Hernández, Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-030091-8.

- Kerényi, Karl 1967, Eleusis: Archetypal Image of Mother and Daughter, Princeton University Press, 1991. ISBN 9780691019154.

- Kerényi, Karl 1976, Dionysos: Archetypal Image of Indestructible Life, Princeton University Press, 1996. ISBN 9780691029153.

- Linforth, Ivan M., The Arts of Orpheus, Berkeley, University of California Press, 1941. Online version at HathiTrust

- Lloyd-Jones, Hugh, Sophocles: Fragments, Edited and translated by Hugh Lloyd-Jones, Loeb Classical Library No. 483. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1996. ISBN 978-0-674-99532-1. Online version at Harvard University Press.

- Kern, Otto. Orphicorum Fragmenta, Berlin, 1922. Internet Archive

- Lucretius, De Rerum Natura, William Ellery Leonard. E. P. Dutton. 1916. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Marcovich, Miroslav, Studies in Graeco-Roman Religions and Gnosticism, BRILL, 1988. ISBN 9789004086241.

- Marsh, Jenny, Cassell's Dictionary of Classical Mythology, Casell & Co, 2001. ISBN 0-304-35788-X. Internet Archive

- McDonough, Sean M. (1999), YHWH at Patmos: Rev. 1:4 in Its Hellenistic and Early Jewish Setting, Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament 2. Reihe, vol. 107, Tübingen, Germany: Mohr Siebeck, ISBN 978-3-16-147055-4, ISSN 0340-9570

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Nauck, Johann August, Tragicorum graecorum fragmenta, Leipzig, Teubner, 1989. Internet Archive

- Nilsson, Martin, P., "Early Orphism and Kindred Religions Movements", The Harvard Theological Review, Vol. 28, No. 3 (Jul., 1935), pp. 181–230. JSTOR 1508326

- Nonnus, Dionysiaca; translated by Rouse, W H D, I Books I–XV. Loeb Classical Library No. 344, Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1940. Internet Archive

- Nonnus, Dionysiaca; translated by Rouse, W H D, III Books XXXVI–XLVIII. Loeb Classical Library No. 346, Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1940. Internet Archive.

- Ogden, Daniel, Drakōn: Dragon Myth and Serpent Cult in the Greek and Roman Worlds, Oxford University Press, 2013. ISBN 978-0-19-955732-5.

- Ovid, Metamorphoses, Brookes More. Boston. Cornhill Publishing Co. 1922. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Parker, Robert (2002), "Early Orphism" in The Greek World, edited by Anton Powell, Routledge, 2002. ISBN 978-1-134-69864-6.

- Parker, Robert (2005) Polytheism and Society at Athens, OUP Oxford, 2005. ISBN 9780191534522.

- Pausanias, Pausanias Description of Greece with an English Translation by W.H.S. Jones, Litt.D., and H.A. Ormerod, M.A., in 4 Volumes. Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1918. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Sara Peterson, An account of the Dionysiac presence in Indian art and culture. Academia, 2016

- Pickard-Cambridge, Arthur, The Theatre of Dionysus at Athens, 1946.

- Plutarch, Moralia, Volume V: Isis and Osiris. The E at Delphi. The Oracles at Delphi No Longer Given in Verse. The Obsolescence of Oracles. Translated by Frank Cole Babbitt. Loeb Classical Library No. 306. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1936. ISBN 978-0-674-99337-2. Online version at Harvard University Press.

- Powell, Barry B., Classical Myth, 5th edition, 2007.

- Ridgeway, William, Origin of Tragedy, 1910. Kessinger Publishing (June 2003). ISBN 0-7661-6221-4.

- Ridgeway, William, The Dramas and Dramatic Dances of non-European Races in special reference to the origin of Greek Tragedy, with an appendix on the origin of Greek Comedy, 1915.

- Riu, Xavier, Dionysism and Comedy, Rowman and Littlefield Publishers (1999). ISBN 0-8476-9442-9.

- Rose, Herbert Jennings, "Iacchus" in The Oxford Classical Dictionary, second edition, Hammond, N.G.L. and Howard Hayes Scullard (editors), Oxford University Press, 1992. ISBN 0-19-869117-3.

- Rutherford, Ian, (2016) Greco-Egyptian Interactions: Literature, Translation, and Culture, 500 BC-AD 300, Oxford University Press, 2016. ISBN 9780191630118.

- Rutherford, William G., (1896) Scholia Aristphanica, London, Macmillan and Co. and New York, 1896. Internet Archive*Seaford, Richard. "Dionysos", Routledge (2006). ISBN 0-415-32488-2.

- Smith, R.R.R., Hellenistic Sculpture, a handbook, Thames & Hudson, 1991, ISBN 0500202494

- Smith, William; Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, London (1873). Online version at the Perseus Digital Library

- Smyth, Herbert Weir, Aeschylus, with an English translation by Herbert Weir Smyth, Volume II, London Heinemann, 1926. Internet Archive

- Sommerstein, Alan H., Aeschylus: Fragments. Edited and translated by Alan H. Sommerstein. Loeb Classical Library No. 505. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2009. ISBN 978-0-674-99629-8. Online version at Harvard University Press.

- Sophocles, The Antigone of Sophocles, Edited with introduction and notes by Sir Richard Jebb, Sir Richard Jebb. Cambridge. Cambridge University Press. 1891. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library

- Strabo, Geography, translated by Horace Leonard Jones; Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press; London: William Heinemann, Ltd. (1924). Books 6–14, at the Perseus Digital Library

- Sutton, Dana F., Ancient Comedy, Twayne Publishers (August 1993). ISBN 0-8057-0957-6.

- Tripp, Edward, Crowell's Handbook of Classical Mythology, Ty Crowell Co; First edition (June 1970). ISBN 069022608X

- Versnel, H. S., “ΙΑΚΧΟΣ. Some Remarks Suggested by an Unpublished Lekythos in the Villa Giulia”, Talanta 4, 1972, 23–38. PDF

- West, M. L. (1983), The Orphic Poems, Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-814854-8.

Further reading

- Livy, History of Rome, Book 39:13, Description of banned Bacchanalia in Rome and Italy

- Detienne, Marcel, Dionysos at Large, tr. by Arthur Goldhammer, Harvard University Press, 1989. ISBN 0-674-20773-4. (Originally in French as Dionysos à ciel ouvert, 1986)

- Albert Henrichs, Between City and Country: Cultic Dimensions of Dionysus in Athens and Attica, (April 1, 1990). Department of Classics, UCB. Cabinet of the Muses: Rosenmeyer Festschrift. Paper festschrift18.

- Sara Peterson, An account of the Dionysiac presence in Indian art and culture. Academia, 2016

- Frazer, James "The Golden Bough"

External links

Library resources aboutDionysus

Media related to Dionysos at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Dionysos at Wikimedia Commons- Ca 2000 images of Bacchus at the Warburg Institute's Iconographic Database

- Iconographic Themes in Art: Bacchus | Dionysos

- Treatise on the Bacchic Mysteries

| Greek deities series | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Dacia | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tribes (List) | |||||||||||||||||

| Kings |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Culture and civilization |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Wars with the Roman Empire |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Roman Dacia / Free Dacians |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Research | |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||