This is an old revision of this page, as edited by JzG (talk | contribs) at 23:27, 29 November 2006 (They have been described as formidable. We have examples of the formidable opposition in Minnesota.). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 23:27, 29 November 2006 by JzG (talk | contribs) (They have been described as formidable. We have examples of the formidable opposition in Minnesota.)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)Personal rapid transit (PRT), also called personal automated transport (PAT), is a category of proposed public transportation systems designed to offer automated on-demand non-stop transportation, usually targeted at urban use, on a network of specially-built guideways.

Originating in the mid 1960s, the design concepts and engineering challenges of PRT are well understood. Elements of PRT design have influenced the design of some existing people mover systems, and many fully automated mass transit systems exist. However, as of 2006, questions remain concerning production and operational costs, safety, aesthetics, and public acceptance of PRT, since there are no completed installations.

In 2005, the two most advanced projects were small-scale schemes: ULTra at Heathrow Airport in London, which is scheduled to be the first public PRT system to open, and one at the Dubai International Financial Center in Dubai. Both are scheduled to come into operation in 2008. Although generally promoted as a potential wide-scale urban transport system, to date only small scale systems and pilot programmes have been constructed. This has led to opposition from some environmental groups, though the European Union has endorsed the concept.

The obstacles faced by any wider PRT implementation have been described as "formidable", though not "unsolvable".

Overview

PRT is a system of small vehicles under independent or semi-independent automatic control, running on fixed guideways. The idea attempts to address a number of perceived weaknesses of public mass transit including fixed timetabling, limited routes, and sharing travel space with unrelated travelers (see comparison below).

In 1988, The Advanced Transit Association published a definition for PRT as follows :

- Fully automated vehicles capable of operation without human drivers.

- Vehicles captive to a reserved guideway.

- Small vehicles available for exclusive use by an individual or a small group, typically 1 to 6 passengers, traveling together by choice and available 24 hours a day.

- Small guideways that can be located aboveground, at groundlevel or underground.

- Vehicles able to use all guideways and stations on a fully coupled PRT network.

- Direct origin to destination service, without a necessity to transfer or stop at intervening stations.

- Service available on demand rather than on fixed schedules.

The definition does not specify a particular technology, such as electric motors, linear motors, magnetic levitation, or rubber wheels. It does not specify whether vehicles are to be supported on the guideway or suspended from the guideway. Instead, it is derived from analysis of the functionality, efficiency, scaleability, and service provided by the total engineering and design of the system. Analogies have been drawn between the characteristics of PRT and those of lean manufacturing, giving rise to the term "lean transit".

Proponents say that the low weight of small vehicles has the important benefit of allowing smaller guideways and support structures compared to other mass transit systems like light rail, translating into lower construction cost, smaller easements, and less visually obtrusive infrastructure.

The concept has been independently reinvented many times since the 1960s. It is considered controversial, and the city-wide deployment with many closely-spaced stations envisaged by proponents has yet to be constructed. Past projects have failed due to lack of financing, cost overruns, regulatory conflicts, political issues and flaws in engineering or design.

From 2002-2005, the European Union conducted an extensive study on the feasibility of PRT in five European cities, and concluded that only barriers to PRT deployment are political. The EDICT project involved researchers, transit consultants and city authorities across Europe. The four PRT schemes studied "showed significant projected benefits and favourable economics." EDICT also conducted focus groups in the five cities, and the overall response was "very positive," particularly among wheelchair users and the blind.

| Similar to automobiles |

|

| Similar to trams, buses, and monorails |

|

| Similar to automated people movers |

|

| Distinct features |

|

History

Some of the key concepts of PRT has been toyed with since before the 1900s, but the full concept of PRT really began around 1953 when Donn Fichter, a city transportation planner, began research on PRT and alternative transportation methods. In 1964, Fichter published a book entitled "Individualized Automated Transit in the City", which proposed an automated public transit system for areas of medium to low population density. In 1966, the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development was asked to "undertake a project to study ... new systems of urban transportation that will carry people and goods ... speedily, safely, without polluting the air, and in a manner that will contribute to sound city planning". The resulting report, entitled "Tomorrow's Transportation: New Systems for the Urban Future," was published in 1968, and proposed the development of PRT, as well as other systems such as dial-a-bus and high-speed intraurban links.

In the late 1960s, the Aerospace Corporation, an independent non-profit corporation set up by Congress, spent substantial time and money on PRT, and performed much of the early theoretical and systems analysis. However, this corporation is not allowed to sell to non-federal government customers. Members of the study team published in Scientific American in 1969, the first wide-spread publication of the concept. The team subsequently published a text entitled Fundamentals of Personal Rapid Transit.

In 1967, aerospace giant Matra started the Aramis project in Paris. After spending about 500 million francs, the project was cancelled when it failed its qualification trials in November 1987. The designers tried to make Aramis work like a "virtual train," but control software issues caused cars to bump unacceptably. The project ultimately failed. It is described in the book Aramis, or the Love of Technology by Bruno Latour.

Between 1970 and 1978, Japan operated a project called Computer-controlled Vehicle System (CVS). In a full scale test facility, 84 vehicles operated at speeds up to 60 km/h on a 4.8 km guideway; one-second headways were achieved during tests. Another version of CVS was in public operation for six months during 1975–76. This system had 12 single-mode vehicles and four dual-mode vehicles on a one-mile track with five stations. This version carried over 800,000 passengers. CVS was cancelled when Japan's Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport declared it unsafe under existing rail safety regulations, specifically in respect of braking and headway distances.

In 1972, President Nixon announced a federal PRT development program, saying "If we can send three men to the moon 200,000 miles away, we should be able to move 200,000 people to work three miles away."

On March 23, 1973, U.S. Urban Mass Transportation Administration (UMTA) administrator Frank Herringer testified before Congress: "A DOT program leading to the development of a short, one-half to one-second headway, high-capacity PRT (HCPRT) system will be initiated in fiscal year 1974." However, this HCPRT program was diverted into a modest technology program. According to PRT supporter J. Edward Anderson, this was "because of heavy lobbying from interests fearful of becoming irrelevant if a genuine PRT program became visible". From that time forward people interested in HCPRT were unable to obtain UMTA research funding.

In 1975, the Morgantown Personal Rapid Transit project was completed. Despite its name and fact that it has five off-line stations that enable non-stop, individually programmed trips that are characteristic of PRT, this is not considered a PRT system by authorities because its vehicles are too heavy and carry too many people, and because most of the time it does not operate in a point-to-point fashion, running instead like an automated people mover from one end of the line to the other. Morgantown is still in continuous operation at West Virginia University in Morgantown, West Virginia with about 15,000 riders per day (as of 2003). It successfully demonstrates automated control, but was not sold to other sites because the heated track has proven too expensive.

In the 1970s and 1980s, Mannesmann Demag and MBB cooperated to build the Cabinentaxi project in Germany. They created an extensive PRT development which was considered fully developed by the German Government and its safety authorities. This project was canceled when a disagreement over the site for the initial implementation coincided with non-defense budget cuts by the German government.

In the 1990s, Raytheon invested heavily in a system called PRT2000 that was based on technology developed by J. Edward Anderson at the University of Minnesota. Raytheon failed to install a contracted system in Rosemont, Illinois, near Chicago, when estimated costs escalated to US$50 million per mile, allegedly due to design changes that increased the weight and cost of the Raytheon system relative to Anderson's original design. In 2000, rights to the technology reverted to the University of Minnesota, and were subsequently purchased by Taxi2000.

In the late 1990s, Douglas Malewicki started the SkyTran project, later renamed UniModal. His proposal calls for vehicles with relatively few moving parts and features such as speech recognition. By using Inductrack passive magnetic levitation, expected vehicle speeds are 100 mph (160 km/h); assumptions of capacities are based on these speeds and on half-second headways.

In 2002, 2getthere, a consortium of Frog Navigation Systems and Yamaha, operated "CyberCabs" at Holland's 2002 Floriade festival. These transported passengers up to 1.2 km on Big Spotters Hill. CyberCab is like a Neighborhood Electric Vehicle, except it steers itself using magnet guidance points embedded in the lane.

In 2003, Ford Research proposed a dual-mode system called PRISM. It would use public guideways with privately-purchased but certified dual-mode vehicles. The vehicles would weigh less than 600 kg (1200 lb), allowing small elevated guideways that could use centralized computer controls and power.

In January 2003, the prototype ULTra ("Urban Light Transport") system from Advanced Transport Systems Ltd. in Cardiff, Wales, was certified to carry passengers by the UK Railway Inspectorate on a 1 km test track. It had successful passenger trials and has met all project milestones for time and cost to date.

In October 2005, ULTra was selected by BAA plc for London's Heathrow Airport. This system is planned to transport 11,000 passengers per day from remote parking lots to the central terminal area. PRT is favored because of zero on-site emissions from the electrically powered vehicles. PRT will also increase the capacity of existing tunnels without enlargement. BAA plans begin operation by the summer of 2008 and to expand the system in 2009.

In June 2006, a Korean/Swedish consortium, Vectus Ltd, started constructing a 400 metre test track in Uppsala, Sweden.

System design

Among the handful of prototype systems (and the larger number that exist on paper) there is a substantial diversity of design approaches, some of which are controversial.

Vehicle design

Vehicle weight influences the size and cost of a system's guideways, which are in turn a major part of the capital cost of the system. Larger vehicles are more expensive to produce, require larger and more expensive guideways, and use more energy to start and stop. If vehicles are too large, point-to-point routing also becomes less economically feasible (for example, when the system at West Virginia University moved from 6-passenger to 20-passenger vehicles, point-to-point operations were largely abandoned). Against this, smaller vehicles have more surface area per passenger (thus have higher total air resistance which dominates the energy cost of keeping vehicles moving at speed) and larger motors are generally more efficient than smaller ones.

The number of riders who will share a vehicle is a key unknown. In the U.S., the average private automobile carries 1.16 persons, and most industrialized countries commonly average below 2 people. Based on these figures, some have suggested that two passengers per vehicle (such as with UniModal), or even a single passenger per vehicle is optimum. Other designs choose larger vehicles, making it possible to accommodate families with small children, riders with bicycles, and disabled passengers with wheelchairs. As of 2006, all systems known to be under active development use four-passenger vehicles.

Propulsion

All current designs are powered by electricity. In order to reduce vehicle weight, power is generally transmitted via lineside conductors rather than using on-board batteries. According to the designer of Skyweb/Taxi2000, J.E. Anderson, the lightest system is a linear induction motor (LIM) on the car, with a stationary conductive rail for both propulsion and braking. LIMs are used in a small number of rapid transit applications, but most designs use rotary motors.

Switching

Most designers avoid track switching, instead advocating vehicle-mounted switches or conventional steering. Designers say that vehicle-switching simplifies the guideway, makes junctions less visually obtrusive and reduces the impact of malfunctions, because a failed switch on one vehicle is less likely to affect other vehicles.

Track switching also greatly increases headway distance. A vehicle must wait for the previous vehicle to clear the track, for the track to switch and for the switch to be verified. If the track switching is faulty, vehicles must be able to stop before reaching the switch, and all vehicles approaching the failed junction would be affected.

Infrastructure design

Guideways

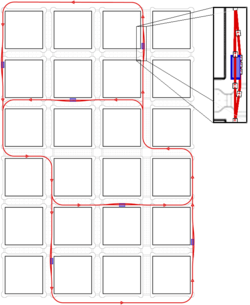

Simplified depiction of a possible PRT network. The blue rectangles indicate stations. The enlarged portion illustrates a station off-ramp.

There is some debate over the best type of guideway. Among the proposals are beams similar to monorails, bridge-like trusses supporting internal tracks, and cables embedded in a roadway. Most designs put the vehicle on top of the track, which reduces visual intrusion and cost as well as facilitating ground-level installation. Overhead suspended vehicles are said to unload the skins of the vehicle, which can therefore be lighter since many materials are stronger in tension than they are in compression. An overhead track is necessarily higher, but may also be narrower. Most designs use the guideway to distribute power and data communications, including to the vehicles. Addressing some issues with prototypes, many proposals also aim to be self clearing in bad weather.

Stations

Proposals usually have stations close together, and located on side tracks so that through traffic can bypass vehicles picking up or dropping off passengers. Each station might have multiple berths, with perhaps one-third of the vehicles in a system being stored at stations waiting for passengers. Stations are envisaged to be minimalistic, and not include facilities such as rest rooms. For elevated stations, an elevator may be required for accessibility.

Some designs have included substantial extra expense for the track needed to decelerate to and accelerate from stations. In at least one system, Aramis, this nearly doubled the width and cost of the required right-of-way and caused the nonstop passenger delivery concept to be abandoned. Other designs have schemes to reduce this cost, for example merging vertically to reduce the footprint.

Operational characteristics

Headway distance

"Headway distance" can mean "distance/time between vehicles (front to back)" or "distance/time between the fronts of vehicles (front to front)". Usually the latter is referred to when talking about capacity and vehicle frequency.

Spacing of vehicles on the guideway influences the maximum passenger capacity of a track, so designers prefer smaller headway distances. Computerized control theoretically permits closer spacing than the two-second headways recommended for cars at speed, since multiple vehicles can be braked simultaneously. There are also prototypes for automatic guidance of private cars based on similar principles.

Very short headways are controversial. Some regulators (e.g. the UK Railway Inspectorate, regulating ULTra) are willing to accept two-second headways. In other jurisdictions, existing rail regulations apply to PRT systems (see CVS, above); these typically calculate headways in terms of absolute stopping distances, which would restrict capacity and make PRT systems unfeasible. No regulatory agency has yet endorsed headways as short as one second, although proponents believe that regulators may be willing to reduce headways as operational experience increases.

Capacity

PRT is usually proposed as an alternative to rail systems, so comparisons tend to be with rail. PRT vehicles seat fewer passengers than trains and buses, and must offset this by higher average speeds and/or shorter headways. Proponents assert that equivalent or higher overall capacity could be achieved by these means. Since there are no full-scale installations, capacity calculations are based on simulation and modeling and are disputed.

With two-second headways and four-person vehicles, PRT can achieve theoretical maximum capacity of 7,200 passengers per hour. However, most estimates assume that vehicles will not generally be filled to capacity, due to the point-to-point nature of PRT. At a more typical average vehicle occupancy of 1.5 persons per vehicle, the maximum capacity is 2,700 passengers per hour. Some researchers have suggested that rush hour capacity can be improved if operating policies support ridesharing.

Capacity is inversely proportional to headway. Therefore, as compared to two-second headways, one-second headways would double the capacity, and half-second headways would quadruple capacity. Although no regulatory agency has as yet (June 2006) approved headways shorter than two seconds, researchers suggest that high capacity PRT (HCPRT) designs could operate safely at half-second headways.

In simulations of rush hour or high-traffic events, about one-third of vehicles on the guideway need to travel empty to resupply stations with vehicles in order to minimize response time. This is analogous to trains and buses travelling nearly empty on the return trip to pick up more rush hour passengers.

Light rail systems can achieve capacities over 7,500 passengers per hour under normal operations. Heavy rail subway systems regularly transport 12,000 passengers per hour or more. As with PRT, these estimates are dependent on having enough trains available. Neither light nor heavy rail scales well for off-peak operation.

The above discussion compares line or corridor capacity and may therefore not be entirely relevant for a networked PRT system. In addition, it has been estimated (see Muller et al TRB 2005 05-0599) that while PRT may need more than one guideway to match the capacity of a conventional system, the capital cost of the multiple guideways may still be less than that of the single guideway conventional system. Thus comparisons of line capacity should include a consideration of per line costs. In addition, PRT systems would require much less horizonal space than existing metro systems, with individual cars being typically around 50% as wide for side-by-side seating configurations, and less than 33% as wide for single-file configurations. This is an important factor in densely-populated, high-traffic areas. A triple-guideway system using cars with single-file seating would have a capacity of over 21,600 - almost twice the capacity of existing metro systems - partly because of the reduced transit times for individual passengers.

Travel speed

For a given peak speed, point-to-point journeys are quicker than scheduled stopping services. While a few PRT designs have operating speeds of 60 mph, most are in the region of 25-45 mph. Rail systems generally have higher maximum speeds, typically 55-80 mph and sometimes well in excess of 100 mph, but average travel speed may be reduced by stopping at additional stations, and by passengers transferring.

Ridership attraction

If PRT designs deliver the claimed benefit of being substantially faster than cars in areas with heavy traffic, simulations suggest that PRT might attract significantly higher than the predicted mode switch from private motoring than is the case for other proposed public transit systems (figures between 25% and 60% have been discussed).

Some skeptics contest the ridership studies, on the grounds that such predictions of human behavior are inherently unreliable.

Control algorithms

One possible control algorithm places vehicles in imaginary moving "slots" that go around the loops of track. Real vehicles are allocated a slot by track-side controllers. On-board computers maintain their position by using a negative feedback loop to stay near the center of the commanded slot. One way vehicles can keep track of their position is by integrating the input from speedometers, using periodic check points to compensate for cumulative errors. Next-generation GPS and radio location can also be used for accurate positioning.

Another style of algorithm assigns a trajectory to a vehicle, after verifying that the trajectory does not violate the safety margins of other vehicles. This permits system parameters to be adjusted to design or operating conditions, and may use slightly less energy.

The maker of the ULTra PRT system reports that testing of its control system shows lateral (side-to-side) accuracy of 1 cm, and docking accuracy better than 2 cm.

Safety

Computer control is considered more reliable than drivers, and PRT designs should, like all public transit, be much safer than private motoring. Most designs enclose the running gear in the guideway to prevent derailments. Grade-separated guideways would prevent conflict with pedestrians or manually-controlled vehicles. Other public transit safety engineering approaches, such as redundancy and self-diagnosis of critical systems, are also included in designs.

The Morgantown system, more correctly described as an Automated Guideway Transit system (AGT), has completed 110 million passenger-miles without serious injury. According to the U.S. Department of Transportation, AGT systems as a group have higher injury rates than any other form of rail-based transit (subway, metro, light rail, or commuter rail) though still much better than ordinary buses or automobiles. More recent research by the British PRT company ATS indicates that AGT systems have a better safety than more conventional, non-automated modes.

As with many current transit systems, passenger safety concerns are likely to be addressed through CCTV monitoring, and communication with a central command center from which engineering or other assistance may be dispatched.

Cost characteristics

Estimates of guideway cost range from US$0.8 million (for MicroRail) to $22 million per mile, with most estimates falling in the $10m to $15m range. These costs may not include the purchase of rights of way or system infrastructure, such as storage and maintenance yards and control centers, and reflect unidirectional travel along one guideway, the standard form of service in current PRT proposals. Bidirectional service is normally provided by moving vehicles around the block. To reach capacities of competing systems, a system requires thousands of vehicles. Some PRT proposals incorporate these costs in their per-mile estimates.

PRT designs generally assume dual-use rights of way, for example by mounting the transit system on narrow poles on an existing street. If dedicated rights of way were required for an application, costs could be considerably higher. If tunneled, small vehicle size can reduce tunnel volume compared with that required for an automated people mover (APM). Dual mode systems would use existing roads, as well as special-purpose PRT guideways. In some designs the guideway is just a cable buried in the street (a technology proven in industrial automation). Similar technology could equally be applied to private automobiles.

A design with many modular components, mass production, driverless operation and redundant systems should in theory result in low operating costs and high reliability. Predictions of low operating cost generally depend on low operations and maintenance costs. Whether these assumptions are valid will not be known until full scale operations are commenced since assumptions regarding reliability cannot be proven by prototype systems. Low operating cost projections are also derived from the relatively high capacity utilization (for a public transport system) of the on-demand service characteristic.

Some planners dispute the cost-estimates of PRT when compared to light rail systems, whose costs vary widely with non-grade-separated streetcars being relatively low cost and systems involving elevated track or tunnels costing up to US$200 million per mile. Systems such as buses and streetcars, which run over the road network, require no further rights of way. This can represent a substantial cost saving over those requiring construction of dedicated routes, but may also result in increased congestion on existing roads.

Ridership and cost

For scheduled mass transit such as buses or trains, there is a fundamental tradeoff between service and cost. This is due to the fact that buses and trains must run on a predefined schedule, even during non-peak times when demand is low and vehicles run nearly empty. For this reason, transportation planners typically control costs by attempting to predict periods of low demand, running on reduced schedules and/or with smaller vehicles at these times. This, however, increases wait times for passengers. In many cities, trains and buses do not run at all at night or on weekends, because the low demand does not justify the cost.

PRT vehicles, in contrast, would only run in response to demand, allowing 24-hour service without many of the cost implications of scheduled mass transit.

Proposals

ULTra ("Urban Light Transport") is a system from Advanced Transport Systems Ltd. in Cardiff, Wales. The ULTra system differs from many other systems in its focus on using off-the-shelf technology and rubber tires running on an open guideway. This approach has resulted in a system that is more economical than designs requiring custom technology. ULTra was recently (October, 2005) selected by BAA plc for London's Heathrow Airport.

Cabinentaxi was a German urban transit development project, undertaken by the joint venture of Mannesmann Demag and MBB under a program of the German BMFT (German Ministry of Research and Development).

UniModal (formerly known as SkyTran) is a concept by Douglas Malewicki for a 160km/h (100mph) personal rapid transit system that would use electric linear propulsion and a form of passive magnetic levitation called Inductrack. No prototype exists.

Opposition and controversy

Opposition has been expressed to PRT schemes and their proponents based on a number of concerns:

Technical feasibility debate

The Ohio, Kentucky, Indiana (OKI) Central Loop Report compared the Taxi 2000 PRT concept proposed by the Skyloop Committee to other transportation modes (bus, light rail and vintage trolley). Consulting engineers with Parsons Brinckerhoff found the Taxi 2000 PRT system had "...significant environmental, technical and potential fire and life safety concerns..." and the PRT system was "...still an unproven technology with significant questions about cost and feasibility of implementation." Skyloop contested this conclusion, arguing that Parsons Brinckerhoff changed several aspects of the system design without consulting with Taxi 2000, then rejected this modified design.

Vukan R. Vuchic, Professor of Transportation Engineering at the University of Pennsylvania and a proponent of light rail, has stated his belief that the PRT concept of small vehicles and expensive guideway makes it impractical for both central cities and lightly travelled suburbs. His opinion is based on the assumption that "guided systems are economically justified only when they have spacious vehicles" and that "a very large number of vehicles cruise empty". The assumptions Vuchic makes are disputed by PRT supporters.

The manufacturers of ULTra acknowledge that current forms of their system would provide insufficient capacity in high density areas such as central London, and that the investment costs for the tracks and stations are comparable to building new roads, making the current version of ULTra more suitable for suburbs and other moderate capacity applications, or as a supplementary system in larger cities.

Regulatory concerns

Possible regulatory concerns include emergency safety, headways, and accessibility for the disabled. If safety or access considerations require the addition of walkways, ladders, platforms or other emergency/disabled access to or egress from PRT guideways, the size of the guideway is substantially increased. Because minimizing guideway size is important to the PRT concept and costs these concerns may be significant barriers to PRT adoption. The U.S. and Europe both have legislation mandating disabled accessibility for public transport systems.

For example, the California Public Utilities Commission states that its "Safety Rules and Regulations Governing Light Rail Transit" (General Order 143-B) and "Rules and Regulations Governing State Safety Oversight of Rail Fixed Guideway Systems" (General Order 164-C) are applicable to PRT . Both documents are available online . The degree to which CPUC would hold PRT to "light rail" and "rail fixed guideway" safety standards as a condition for safety certification is not clear.

Other concerns

Concerns have been expressed about the visual impact of elevated guideways and stations. The 2001 OKI Report stated that Skyloop's elevated guideways would create visual barriers, loss of privacy, and would be inconsistent with the character of historic neighborhoods. Some in the business community in Cincinnati were opposed to Skyloop's elevated guideway because it would remove potential customers from the street level where their shops are advertised.

Some have also objected to PRT promotion on the grounds that it is a distraction from other, more established transit solutions. Objectors claim that advocacy for PRT has reduced support for other alternatives to private motoring. There is, however, no evidence that the rejection of light rail had anything to do with the existence of a competing PRT proposal.

As with other modes of public transit, there are also concerns about policing against terrorism and vandalism, although the impact of such terrorism might be minimized by the lack of large concentrations of people.

See also

- ULTra - planned to be built at London's Heathrow airport

- Morgantown Personal Rapid Transit, 1975-present

- Cabinentaxi - 1970s West German PRT system

- UniModal - an unimplemented concept also known as SkyTran

- People mover

- Light Rail

External links

Pilots and prototypes

- Austrans, Australia

- ULTra (Urban Light Transport), Cardiff Wales, UK

- Cabintaxi PRT System Hagen, Germany

- ParkShuttle, Capelle aan den IJssel, Netherlands

- MicroRail, from MegaRail Transportation, Fort Worth, Texas

- Vectus Ltd., - 385 metre test track under construction in Uppsala, Sweden

- SkyWebExpress, Minneapolis, Minnesota, U.S. - 18 metre sample guideway

Proposals

- Autoway— For passengers and light freights. Virginia, USA

- EcoTaxi — Finnish version of PRT, termed "Automated People and Goods Mover" (APGM)

- MagTube, a dual freight and passenger system based on maglev technology. California, USA

- RUF, Dual-mode — Denmark

- Intelligent Transportation - Ultra light, passenger and cargo networks

- Skycab — A Swedish concept

- UniModal (also known as SkyTran), a hypothetical project

- Thuma —A system for varying sizes of containers

- Tritrack — Dual-mode system, but its PRT part is necessary for viability

Advocacy

- ATRA, The Advanced Transit Association, a professional group

- Open Directory: Personal Rapid Transit

- Transportationet PRT from engineering and law point of view. Site by Oded Roth, member of Israeli Retzef team

- Skyloop

- IST Institute for Sustainable Transportation, Sweden

PRT skepticism and criticism

- Planetizen Article on PRT and "Gadgetbahnen"

- The Road Less Traveled: The pros and cons of personal rapid transit" by Troy Pieper

References

- Daily Telegraph opinion column, from October 20 2005

- According to cities21.org, the primary source is an article in the Middle East Economic Digest (MEED) (subscription required).

- resolution opposing PRT from Sierra Club, Minnesota

- ^ Moving ahead with PRT

- Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Automated People Movers, 2005

- Leone M.Cole, Harold W. Merritt (1968), Tomorrow's Transportation: New Systems for the Urban Future, U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Metropolitan Development

- Jack Irving, with Harry Bernstein, C. L. Olson and Jon Buyan (1978), Fundamentals of Personal Rapid Transit, D.C. Heath and Company

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - In his budget speech to Congress in January 1972, in which he announced a federal PRT development program, President Nixon said: "If we can send three men to the moon 200,000 miles away, we should be able to move 200,000 people to work three miles away." Reported in Some lessons from the history of personal rapid transit, a paper by J E Anderson of Taxi 2000

- J. Edward Anderson (1997). "The Historical Emergence and State-of-the-Art of PRT Systems".

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - Peter Samuel (1996), Status Report on Raytheon's PRT 2000 Development Project, ITS International

- Peter Samuel (1999), Raytheon PRT Prospects Dim but not Doomed, ITS International

- ^ "(PDF) A Rebuttal to the Central Area Loop Study Draft Final Report" (PDF). 2001.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - Johnson, Robert E. (2005). "Doubling Personal Rapid Transit Capacity with Ridesharing". Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - Buchanan, M. (2005). "(PDF) Emerging Personal Rapid Transit Technologies" (PDF). Proceedings of the AATS conference, Bologna, Italy, 7 November-8 November 2005.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - "Personal Automated Transportation: Status and Potential of Personal Rapid Transit, p.89" (PDF). Advanced Transit Association. 2003.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessdaymonth=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "Infrastructure cost comparisons" (Microsoft Word). ATS Ltd.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessdaymoth=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "Ohio, Kentucky, Indiana (OKI) Central Loop Report".

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|yesr=ignored (help) - Vuchic, Vukan R (September/October, 1996). "Personal Rapid Transit: An Unrealistic System". Urban Transport International (Paris), (No. 7, September/October, 1996).

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link)

Additional references

- Transit Systems Theory, J.E. Anderson, 1978

- Control of Personal Rapid Transit Systems, J.E. Anderson, 2003 (PDF)

- Systems Analysis of Urban Transportation Systems, Scientific American, 1969, 221:19-27

- Individualized Automated Transit in the City, Donn Fichter, 1964

- advancedtransit.org - A history of PRT.