This is an old revision of this page, as edited by MaxwellMolecule (talk | contribs) at 01:50, 19 November 2019 (Undid revision 926878908 by 106.67.87.236 (talk)). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 01:50, 19 November 2019 by MaxwellMolecule (talk | contribs) (Undid revision 926878908 by 106.67.87.236 (talk))(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) For other uses, see Collision (disambiguation). "Jostle" redirects here. For the racehorse, see Jostle (horse).A collision is the event in which two or more bodies exert forces on each other in about a relatively short time. Although the most common use of the word collision refers to incidents in which two or more objects collide with great force, the scientific use of the term implies nothing about the magnitude of the force.

Some examples of physical interactions that scientists would consider collisions are the following:

- When an insect lands on a plant's leaf, its legs are said to collide with the leaf.

- When a cat strides across a lawn, each contact that its paws make with the ground is considered a collision, as well as each brush of its fur against a blade of grass.

- When a boxer throws a punch, his fist is said to collide with the opponent's body.

- When an astronomical object merges with a black hole, they are considered to collide.

Some colloquial uses of the word collision are the following:

- A traffic collision involves at least one automobile.

- A mid-air collision occurs between airplanes.

- A ship collision accurately involves at least two moving maritime vessels hitting each other. (See allision below.)

Overview

Collision is short-duration interaction between two bodies or more than two bodies simultaneously causing change in motion of bodies involved due to internal forces acted between them during this. Collisions involve forces (there is a change in velocity). The magnitude of the velocity difference just before impact is called the closing speed. All collisions conserve momentum. What distinguishes different types of collisions is whether they also conserve kinetic energy. The Line of impact is the line that is colinear to the common normal of the surfaces that are closest or in contact during impact. This is the line along which internal force of collision acts during impact, and Newton's coefficient of restitution is defined only along this line. Collisions are of three types:

- perfectly elastic collision

- inelastic collision

- perfectly inelastic collision.

Specifically, collisions can either be elastic, meaning they conserve both momentum and kinetic energy, or inelastic, meaning they conserve momentum but not kinetic energy.

An inelastic collision is sometimes also called a plastic collision. A “perfectly inelastic” collision (also called a "perfectly plastic" collision) is a limiting case of inelastic collision in which the two bodies coalesce after impact.

The degree to which a collision is elastic or inelastic is quantified by the coefficient of restitution, a value that generally ranges between zero and one. A perfectly elastic collision has a coefficient of restitution of one; a perfectly inelastic collision has a coefficient of restitution of zero.

Types of collisions

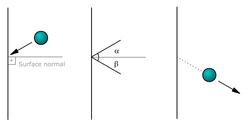

There are two types of collisions between two bodies - 1) Head-on collisions or one-dimensional collisions - where the velocity of each body just before impact is along the line of impact, and 2) Non-head-on collisions, oblique collisions or two-dimensional collisions - where the velocity of each body just before impact is not along the line of impact.

According to the coefficient of restitution, there are two special cases of any collision as written below:

- A perfectly elastic collision is defined as one in which there is no loss of kinetic energy in the collision. In reality, any macroscopic collision between objects will convert some kinetic energy to internal energy and other forms of energy, so no large-scale impacts are perfectly elastic. However, some problems are sufficiently close to perfectly elastic that they can be approximated as such. In this case, the coefficient of restitution equals one.

- An inelastic collision is one in which part of the kinetic energy is changed to some other form of energy in the collision. Momentum is conserved in inelastic collisions (as it is for elastic collisions), but one cannot track the kinetic energy through the collision since some of it is converted to other forms of energy. In this case, coefficient of restitution does not equal one.

In any type of collision there is a phase when for a moment colliding bodies have the same velocity along the line of impact.Then the kinetic energy of bodies reduces to its minimum during this phase and may be called a maximum deformation phase for which momentarily the coefficient of restitution becomes one.

Collisions in ideal gases approach perfectly elastic collisions, as do scattering interactions of sub-atomic particles which are deflected by the electromagnetic force. Some large-scale interactions like the slingshot type gravitational interactions between satellites and planets are perfectly elastic.

Collisions between hard spheres may be nearly elastic, so it is useful to calculate the limiting case of an elastic collision. The assumption of conservation of momentum as well as the conservation of kinetic energy makes possible the calculation of the final velocities in two-body collisions.

Allision

In maritime law, it is occasionally desirable to distinguish between the situation of a vessel striking a moving object, and that of it striking a stationary object. The word "allision" is then used to mean the striking of a stationary object, while "collision" is used to mean the striking of a moving object. So when two vessels run against each other, it is called collision whereas when one vessel ran against another, it is considered allision. The fixed object could also include a bridge or dock. While there is no huge difference between the two terminologies and often they are even used interchangeably, it is important to determine the difference because it helps clarify the circumstances of emergencies and adapt accordingly. In the case of Vane Line Bunkering, Inc. v. Natalie D M/V, it was established that there was the presumption that the moving vessel is at fault, stating that "presumption derives from the common-sense observation that moving vessels do not usually collide with stationary objects unless the vessel is mishandled in some way.” This is also referred to as The Oregon Rule.

Analytical vs. numerical approaches towards resolving collisions

Relatively few problems involving collisions can be solved analytically; the remainder require numerical methods. An important problem in simulating collisions is determining whether two objects have in fact collided. This problem is called collision detection.

| This section may require cleanup to meet Misplaced Pages's quality standards. No cleanup reason has been specified. Please help improve this section if you can. (February 2011) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Examples of collisions that can be solved analytically

Billiards

Collisions play an important role in cue sports. Because the collisions between billiard balls are nearly elastic, and the balls roll on a surface that produces low rolling friction, their behavior is often used to illustrate Newton's laws of motion. After a zero-friction collision of a moving ball with a stationary one of equal mass, the angle between the directions of the two balls is 90 degrees. This is an important fact that professional billiards players take into account, although it assumes the ball is moving frictionlessly across the table rather than rolling with friction. Consider an elastic collision in 2 dimensions of any 2 masses m1 and m2, with respective initial velocities u1 and u2 where u2 = 0, and final velocities V1 and V2. Conservation of momentum gives m1u1 = m1V1+ m2V2. Conservation of energy for an elastic collision gives (1/2)m1|u1| = (1/2)m1|V1| + (1/2)m2|V2|. Now consider the case m1 = m2: we obtain u1=V1+V2 and |u1| = |V1|+|V2|. Taking the dot product of each side of the former equation with itself, |u1| = u1•u1 = |V1|+|V2|+2V1•V2. Comparing this with the latter equation gives V1•V2 = 0, so they are perpendicular unless V1 is the zero vector (which occurs if and only if the collision is head-on).

Perfectly inelastic collision

In a perfectly inelastic collision, i.e., a zero coefficient of restitution, the colliding particles coalesce. It is necessary to consider conservation of momentum:

where v is the final velocity, which is hence given by

The reduction of total kinetic energy is equal to the total kinetic energy before the collision in a center of momentum frame with respect to the system of two particles, because in such a frame the kinetic energy after the collision is zero. In this frame most of the kinetic energy before the collision is that of the particle with the smaller mass. In another frame, in addition to the reduction of kinetic energy there may be a transfer of kinetic energy from one particle to the other; the fact that this depends on the frame shows how relative this is. With time reversed we have the situation of two objects pushed away from each other, e.g. shooting a projectile, or a rocket applying thrust (compare the derivation of the Tsiolkovsky rocket equation).

Examples of collisions analyzed numerically

Animal locomotion

Collisions of an animal's foot or paw with the underlying substrate are generally termed ground reaction forces. These collisions are inelastic, as kinetic energy is not conserved. An important research topic in prosthetics is quantifying the forces generated during the foot-ground collisions associated with both disabled and non-disabled gait. This quantification typically requires subjects to walk across a force platform (sometimes called a "force plate") as well as detailed kinematic and dynamic (sometimes termed kinetic) analysis.

Collisions used as an experimental tool

Collisions can be used as an experimental technique to study material properties of objects and other physical phenomena.

Space exploration

An object may deliberately be made to crash-land on another celestial body, to do measurements and send them to Earth before being destroyed, or to allow instruments elsewhere to observe the effect. See e.g.:

- During Apollo 13, Apollo 14, Apollo 15, Apollo 16 and Apollo 17, the S-IVB (the rocket's third stage) was crashed into the Moon in order to perform seismic measurement used for characterizing the lunar core.

- Deep Impact

- SMART-1 - European Space Agency satellite

- Moon impact probe - ISRO probe

Mathematical description of molecular collisions

Let the linear, angular and internal momenta of a molecule be given by the set of r variables { pi }. The state of a molecule may then be described by the range δwi = δp1δp2δp3 ... δpr. There are many such ranges corresponding to different states; a specific state may be denoted by the index i. Two molecules undergoing a collision can thus be denoted by (i, j) (Such an ordered pair is sometimes known as a constellation.) It is convenient to suppose that two molecules exert a negligible effect on each other unless their centre of gravities approach within a critical distance b. A collision therefore begins when the respective centres of gravity arrive at this critical distance, and is completed when they again reach this critical distance on their way apart. Under this model, a collision is completely described by the matrix , which refers to the constellation (i, j) before the collision, and the (in general different) constellation (k, l) after the collision. This notation is convenient in proving Boltzmann's H-theorem of statistical mechanics.

Attack by means of a deliberate collision

Types of attack by means of a deliberate collision include:

- striking with the body: unarmed striking, punching, kicking

- striking with a weapon, such as a sword, club or axe

- ramming with an object or vehicle, e.g.:

- a car deliberately crashing into a building to break into it

- a battering ram, medieval weapon used for breaking down large doors, also a modern version is used by police forces during raids

An attacking collision with a distant object can be achieved by throwing or launching a projectile.

See also

- Ballistic pendulum

- Car accident

- Coefficient of restitution

- Collision (telecommunications)

- Collision detection

- Elastic collision

- Friction

- Head-on collision

- Impact crater

- Impact event

- Inelastic collision

- Kinetic theory

- collisions between molecules - Mid-air collision

- Projectile

- Satellite collision

- Space debris

- Train wreck

Notes

- merriam-webster.com, "Allision". Accessed November 7, 2014.

- "Admiralty Court Rejects Equal Division Rule and Apportions Damages Unequally in Multiple Fault Collision Case". Columbia Law Review. 63 (3): 554 footnote 1. March 1963. JSTOR 1120603.

The striking by a vessel of a fixed object such as a bridge, technically termed 'allision' rather than 'collision'

. - Talley, Wayne K. (January 1995). "Safety Investments and Operating Conditions: Determinants of Accident Passenger-Vessel Damage Cost". Southern Economic Journal. 61 (3): 823, note 11. JSTOR 1061000.

collision—vessel struck or was struck by another vessel on the water surface, or struck a stationary object, not another ship (an allision)

. - "Allision", The Free Dictionary, retrieved 2018-08-28

- "You Say Collision, I Say Allision; Let's Sort the Whole Thing Out | response.restoration.noaa.gov". response.restoration.noaa.gov. Retrieved 2018-08-28.

- Judge, ELDON E. FALLON, District. "VANE LINE BUNKERING, INC. | Civil Action No. 17-1882. | 20180222d82 | Leagle.com". Leagle. Retrieved 2018-08-28.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - See 158 U.S. 186 - The Oregon, especially paragraph 10.

- Alciatore, David G. (January 2006). "TP 3.1 90° rule" (PDF). Retrieved 2008-03-08.

References

- Tolman, R. C. (1938). The Principles of Statistical Mechanics. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Reissued (1979) New York: Dover ISBN 0-486-63896-0.

External links

- Three Dimensional Collision - Oblique inelastic collision between two homogeneous spheres.

- One Dimensional Collision - One Dimensional Collision Flash Applet.

- Two Dimensional Collision - Two Dimensional Collision Flash Applet.

, which refers to the constellation (i, j) before the collision, and the (in general different) constellation (k, l) after the collision.

This notation is convenient in proving Boltzmann's

, which refers to the constellation (i, j) before the collision, and the (in general different) constellation (k, l) after the collision.

This notation is convenient in proving Boltzmann's