This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Chiswick Chap (talk | contribs) at 14:06, 16 March 2020 (→Paradise: Earthly not Celestial Paradise, as in Dante's ''Paradiso'', ref). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 14:06, 16 March 2020 by Chiswick Chap (talk | contribs) (→Paradise: Earthly not Celestial Paradise, as in Dante's ''Paradiso'', ref)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| An editor has nominated this article for deletion. You are welcome to participate in the deletion discussion, which will decide whether or not to retain it.Feel free to improve the article, but do not remove this notice before the discussion is closed. For more information, see the guide to deletion. Find sources: "Aman" Tolkien – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR%5B%5BWikipedia%3AArticles+for+deletion%2FAman+%28Tolkien%29%5D%5DAFD |

| Aman | |

|---|---|

| J. R. R. Tolkien's legendarium location | |

| In-universe information | |

| Other name(s) | the Undying Lands, Eressëa, the Deathless Lands, the Blessed Realm, the Uttermost West |

| Type | Land of the Ainur and the Elves Continent |

| Ruler | Manwë |

| Location | on the west of the Great Sea, far to the West of Middle-earth |

| Lifespan | Years of the Trees – forever |

| Founder | Valar |

| Notable places | Valinor, Eldamar, Araman, Avathar |

Aman is a fictional place in J. R. R. Tolkien's legendarium, also known as the Undying Lands, the Blessed Realm or the Uttermost West, the last sometimes simply the West. It is the home of revered immortal beings: the Valar, and three kindreds of Elves: the Vanyar, some of the Noldor, and some of the Teleri.

Scholars have noted the similarity of Tolkien's myth of the attempt of Númenor to capture Aman to the biblical Tower of Babel and the ancient Greek Atlantis, and the resulting destruction in both cases.

Others have compared the account of the beautiful Elvish part of the Undying Lands to the Middle English poem Pearl, stating that the closest literary equivalents of Tolkien's descriptions of these lands are the imrama Celtic tales such as those about Saint Brendan from the early Middle Ages. The Christian theme of good and light (from Valinor) opposing evil and dark (from Mordor) has also been discussed.

Fictional setting

Geography

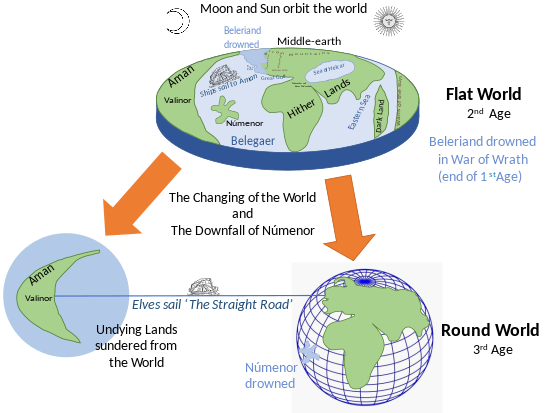

Aman was a continent far to the west of Middle-earth across the great ocean Belegaer. The island of Tol Eressëa lies just off its eastern shore. At the end of the Second Age, Aman was removed from the surface of the Earth to another realm, and is no longer reachable by ordinary means of travel.

Eldamar

Eldamar is "Elvenhome", the "coastal region of Aman, settled by the Elves", wrote Tolkien. Eldamar was included in Valinor, which meant the "land of the Valar", but was the true Eldarin name of Aman, according to Tolkien. In The Hobbit it is referred to as "Faerie".

The size of Eldamar is unknown, but the area between the Bay of Eldamar and the Pelóri was probably at least a few dozen miles wide; Eldamar also consisted of the shore of Taniquetil and the Calacirya pass where Tirion was built. The shore probably extended hundreds of miles to the north of the Calacirya.

The land is regarded as being well-wooded, or at least containing areas of forest, as Finrod was recounted as "walking with his father under the trees in Eldamar" and the Teleri needed timber to build their ships.

The city of the Teleri, on the north shore of the Bay is Alqualondë, or Haven of the Swans, whose halls and mansions are made of pearl. The harbour is entered through a natural arch of rock, and the beaches are strewn with gems given by the Noldor.

In the bay, and part of Eldamar, is Tol Eressëa. This is a large island that was at one time adrift, until Ulmo (or with Uin the great right whale) ran it aground in the bay.

South of Eldamar is Avathar; to the north is Araman.

Calacirya

Calacirya (meaning "Light Cleft" in Tolkien's artificial Elvish language Quenya) is the pass in the Pelóri mountains north of Taniquetil where the elven city Tirion was set on Túna hill. After the hiding of Valinor this was the only gap through the mountains of Aman. The Valar would have closed the mountains entirely but, realizing that the Elves, even the Vanyar, needed to be able to breathe the outside air, they kept Calacirya open. They also did not want to wholly separate the Vanyar and Noldor from the Teleri on the coast.

The name refers to the light of the Two Trees that streamed through the pass into the world beyond, the only source of light other than the stars before the coming of the sun and moon.

Tirion

The city of the Noldor (and for a time the Vanyar also) is Tirion, which was built on the hill of Túna, raised inside the Calacirya mountain pass, just north of Taniquetil, facing both the Two Trees and the starlit seas.

The city had a central square at the top of the hill and a tower called the Mindon Eldaliéva, a beacon visible from the seashore miles to the east.

Alqualondë

Alqualondë (meaning Swanhaven in Quenya) is the chief city of the Teleri on the eastern shores of Valinor.

Alqualondë is perhaps best known as the site of the first Kinslaying as recounted in The Silmarillion. The city is said to be north and east of Tirion between the Calacirya and Araman in northern Eldamar.

The city was walled and built in a natural harbour made of rock. Other than the great harbours where the Teleri ships were moored, it also housed the tower of Olwë, brother of Thingol. The city was covered with pearls which the Teleri found in the seas and jewels obtained from the Noldor.

History

After the destruction of Almaren in ancient times, the Valar retreated to Aman, and established there the realm of Valinor. Seeking to isolate themselves, they raised a great mountain fence, called the Pelóri, on the eastern coast, and set the Enchanted Isles in the ocean to prevent travellers by sea from reaching Aman.

Outside the wall of the Pelóri the Valar left two lands: Araman to the northeast and Avathar to the southeast. Ungoliant, an ancient evil being who chose the form of a great spider, lived in Avathar. When Melkor was released from captivity, he fled to Avathar, scaled the mountains with the help of Ungoliant, and wrought destruction in Aman: he persuaded Ungoliant to kill the Two Trees of Valinor and take from them what energy she could to quench her hunger, for Ungoliant was always hungry. (See also Shelob.)

Soon after that, the first Kinslaying occurred when Fëanor led the host of Noldor to Alqualondë and slaughtered the Teleri for refusing Fëanor use of their ships. When Fëanor left Valinor he needed ships to get to Middle-earth without great loss, but the Noldor possessed no ships, and Fëanor feared that any delay in their departure would cause the Noldor to reconsider. The Noldor, led by Fëanor and his seven sons, tried to persuade their friends, the Teleri of Alqualondë, to give him their ships. However, the Teleri would not help in any way against the will of the Valar, and in fact attempted to persuade their friends to reconsider and stay in Aman. In their insanity and rage, the Noldor started taking the ships and sailing them away. This angered the Teleri, and they threatened the Noldor with rocks and arrows, and they threw many of Fëanor's Noldor out of the ships into the harbour (though probably not killing any of them). They also began to attempt to block the harbour, but it is only slightly possible that the Teleri drew first blood.

Then the Noldor drew swords, and the Teleri their bows, and there was a bitter fight that seemed evenly matched, if not even in favour of the Teleri, until the second Host of the Noldor, led by Fingon, arrived together with some of Fingolfin's people. Misunderstanding the situation, they assumed the Teleri had attacked the Noldor under orders of the Valar, and they joined the fight. In the end many Teleri were slain and the ships taken, and many of the stolen ships were wrecked in the waves. All that continued towards Middle-earth were therefore cursed by Mandos.

The first possibly mortal peredhel (half human half elf) to succeed in navigating to and passing the Isles of Enchantment was Eärendil, who came to Valinor to seek the aid of the Valar against Melkor, now called Morgoth. His quest was successful, the Valar went to war again, and also decided to remove the Isles.

Soon after this, the great island of Númenor was raised out of Belegaer, close to the shores of Aman, and the Three Houses of the Edain were brought to live there. Henceforth, they were called the Dúnedain, or Men of the West, and were blessed with many gifts by the Valar and the Elves of Tol Eressëa. The Valar feared — rightly — that the Númenóreans would seek to enter Aman to gain immortality (even though a mortal in Aman remains mortal, because it is not their final destination), so they forbade them from sailing west of sight of the westernmost promontory of Númenor. In time, deceived by the lies of Sauron, the Númenóreans violated the Ban of the Valar, and sailed to Aman with a great army under the command of Ar-Pharazôn the Golden. Eru collapsed a part of the Pelóri on this army, trapping it but not killing it. It is said that the army still lives underneath the pile of rock.

In response, Manwë called on Eru, who removed Aman from the spheres of the world. The earth, at this time, was flat. Eru split it in two, and then made the half containing Middle-earth spherical, so that a mariner sailing west along Eärendil's route would simply emerge in the far east. For the Elves, however, Eru crafted a Straight Road that peels away from the curvature of the earth and passes to the now-alien land of Aman. Besides the Elves, a few are known to have passed along this road: Gandalf, Bilbo and Frodo Baggins, Samwise Gamgee, and Gimli.

Reception

Paradise

Keith Kelly and Michael Livingston, writing in Mythlore, notes that Frodo's final destination is Aman, the Undying Lands. In Tolkien's mythology, they write, the islands of Aman were initially just the dwelling-places of the Valar who helped The One, Eru Iluvatar, to create the world, but gradually some of the immortal and ageless Elves were allowed to live there as well, sailing across the ocean to the West. After the fall of Númenor and the reshaping of the world, Aman becomes the place "between (sic) Over-heaven and Middle-earth", accessible only in special circumstances like Frodo's, allowed to come to Aman through the offices of the Valar and of Gandalf, one of the Valar's emissaries, the Maiar. However, Aman is not, they write, exactly paradise: firstly, being there does not confer immortality, contrary to what the Númenoreans supposed; and secondly, those mortals like Frodo who are allowed to go there will eventually choose to die. They note that in another of Tolkien's writings, Leaf by Niggle, understood to be a journey through Purgatory (the Catholic precursor stage to paradise), Tolkien avoids describing paradise at all; they suggest that to Tolkien, it is impossible to describe Heaven, and it might be sacrilege to make the attempt. The Tolkien scholar Michael D. C. Drout comments that Tolkien's accounts of Eldamar "give us a good idea of his conceptions of absolute beauty," and notes that these resemble the paradise described in the Middle English poem Pearl. The Tolkien critic Tom Shippey adds that in 1927 Tolkien wrote a poem, The Nameless Land, in the complex stanza-form of Pearl which spoke of a land further away than paradise, and more beautiful than the Irish Tir nan Og, the deathless otherworld. Kelly and Livingston similarly draw on Pearl, noting that it states that "fair as was the hither shore, far lovelier was the further land" where the Dreamer could not pass. So, they write, each stage looks like paradise, until the traveller realises that beyond it lies something even more parasisiacal, glimpsed and beyond description. The Earthly Paradise can be described; Aman, the Undying Lands, can thus be compared to the Garden of Eden, the paradise that the Bible says once existed upon Earth before the Fall of Man, while the Celestial Paradise lies "beyond (or above)", as it does, they note, in Dante's Paradiso.

Good against evil

The scholar of English literature Marjorie Burns writes that one of the female Vala, Varda (Elbereth to the Elves) is sung to by the Elf-queen of Middle-earth Galadriel. Burns notes that Varda "sits far off in Valinor on Oiolossë", looking from her mountain-peak tower in Aman towards Middle-earth and the Dark Tower of Sauron in Mordor: in her view, the white benevolent feminine symbol opposing the evil masculine symbol. Further, Burns suggests, Galadriel is an Elf from Valinor "in the Blessed Realm", bringing Varda's influence with her to Middle-earth. This is seen in the phial of light that she gives to Frodo, and that Sam uses to defeat the evil giant spider Shelob: Sam invokes Elbereth when he uses the phial. Burns comments that Sam's request to the "Lady" sounds distinctly Catholic, and that the "female principle, embodied in Varda of Valinor and Galadriel of Middle-earth, most clearly represents the charitable Christian heart."

Atlantis, Babel

Kelly and Livingston state that while Aman could be home to Elves as well as Valar, the same was not true of mortal Men. The "prideful" Men of Númenor, imagining they could acquire immortality by capturing the physical lands of Aman, were punished by the destruction of their own island, which is engulfed by the sea, and the permanent removal of Aman "from the circles of the world". Kelly and Livingston note the similarity to the ancient Greek myth of Atlantis, the greatest human civilisation lost beneath the sea; and the resemblance to the biblical tale of the Tower of Babel, the hubristic and "sacrilegious" attempt by mortal men to climb up into God's realm.

Celtic influence

The scholar of English literature Paul Kocher writes that the region of Aman, the Undying Lands of the Uttermost West including Eldamar and Valinor, is "so far outside our experience that Tolkien can only ask us to take it completely on faith." Kocher comments that these lands have an integral place both geographically and spiritually in Middle-earth, and that their closest literary equivalents are the imrama Celtic tales from the early Middle Ages. The imrama tales describe how Irish adventurers such as Saint Brendan sailed the seas looking for the "Land of Promise". He notes that it is certain that Tolkien knew these stories as in 1955 he wrote a poem, entitled Imram, about Brendan's voyage.

See also

References

- ^ Oberhelman 2013.

- Kept in a folder labelled "Phan, Mbar, Bal and other Elvish etymologies", published in Parma Eldalamberon, n°17.

- See Parma Eldalamberon, n°17, p. 106.

- J. R. R. Tolkien. 1983. The Book of Lost Tales, Part One: Part One. Retrieved on December 18. 2014

- ^ Kelly & Livingston 2009.

- ^ Drout 2007.

- ^ Shippey 2005, pp. 324–328.

- ^ Burns 2005, pp. 152–154.

- Cite error: The named reference

Kelly Livingston 2009was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Kocher 1974.

Sources

Primary

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1955). The Return of the King. The Lord of the Rings. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. Appendix. OCLC 519647821.

- Tolkien, J.R.R. Christopher Tolkien (ed.). The Silmarillion. Ballantine Books. pp. 59, 62, 75, 88, 114, 298.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1980). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). Unfinished Tales. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-29917-3.

Secondary

- Burns, Marjorie (2005). Perilous Realms: Celtic and Norse in Tolkien's Middle-earth. University of Toronto Press. pp. 152-154 (Elbereth/Varda in Valinor vs Galadriel in Middle-earth, formerly of Valinor). ISBN 978-0802038067.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Day, David (1996). Tolkien: the illustrated encyclopaedia. Simon & Schuster. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-684-83979-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Drout, Michael D. C. (2007). Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). Eldamar. CRC Press. p. 145. ISBN 978-0-415-96942-0.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Duriez, Colin (1992). The J.R.R. Tolkien Handbook: A Comprehensive Guide to His Life, Writings, and World of Middle-earth. Baker Book House. pp. 103ff. ISBN 978-0-8010-3014-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hostetter, Carl F. (2007). Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). The Languages of Arda. CRC Press. p. 337. ISBN 978-0-415-96942-0.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kelly, A. Keith; Livingston, Michael (2009). "'A Far Green Country: Tolkien, Paradise, and the End of All Things in Medieval Literature". Mythlore. 27 (3). Article 13.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: location (link) - Kocher, Paul (1974) . Master of Middle-Earth: The Achievement of J.R.R. Tolkien. Penguin Books. pp. 14-18 and 79-82 (Valinor, Eldamar, Undying Lands, origins in Celtic tales). ISBN 0140038779.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Manguel, Alberto; Guadalupi, Gianni (2000). The Dictionary of Imaginary Places. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-15-600872-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Oberhelman, David D. (2013) . Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). Valinor. Routledge. pp. 692-693 (domain of Valar and Elves and the Two Trees, and Halls of Mandos for spirits of Elves and Men after death, all on Aman, hiding of Aman/Valinor & end of 'The Straight Road' to Aman). ISBN 978-0-415-86511-1.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|work=ignored (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Shippey, Tom (2005) . The Road to Middle-Earth (Third ed.). The Lost Straight Road: HarperCollins. pp. 324–328. ISBN 978-0261102750.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)