This is an old revision of this page, as edited by MicaelTru (talk | contribs) at 10:39, 21 December 2006 (→The New Testament). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 10:39, 21 December 2006 by MicaelTru (talk | contribs) (→The New Testament)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| Editing of this article by new or unregistered users is currently disabled. See the protection policy and protection log for more details. If you cannot edit this article and you wish to make a change, you can submit an edit request, discuss changes on the talk page, request unprotection, log in, or create an account. |

|

The Bible is

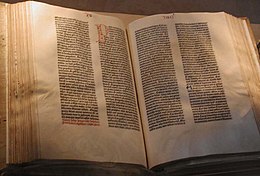

The Gutenberg Bible displayed by the United States Library of Congress |

The word "Bible" refers to the canonical collections of sacred writings of Judaism and Christianity.

Judaism's Bible is often referred to as the Tanakh, or Hebrew Bible, which includes the sacred texts common to both the Christian and Jewish canons. The Christian Bible is also called the Holy Bible, Scriptures, or Word of God. The Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Old Testament canons contain books not found in the Tanakh, but which were found in the Greek Septuagint.

More than 14,000 manuscripts and fragments of the Hebrew Tanakh exist, as do numerous copies of the Septuagint, and 5,300 manuscripts of the Greek New Testament, more than any other work of antiquity.

Derivation of term Bible

According to the Online Etymology Dictionary the word bible is from Anglo-Latin biblia, traced from the same word through Medieval Latin and Late Latin, as used in the phrase biblia sacra ("holy books"). This then stemmed from the term (Greek: Template:Polytonic ta biblia ta hagia, "the holy books"), which derived from biblion ("paper" or "scroll", the ordinary word for "book"), which was originally a diminutive of byblos ("Egyptian papyrus"), possibly so called from the name of the Phoenician port from which Egyptian papyrus was exported to Greece.

Biblical scholar Mark Hamilton states that the Greek phrase ta biblia ("the books") was "an expression Hellenistic Jews used to describe their sacred books several centuries before the time of Jesus," and would have referred to the Septuagint. The Online Etymology Dictionary states, "The Christian scripture was referred to in as Ta Biblia as early as c.223."

The Online Etymology Dictionary continues stating that the word "Bible" replaced Old English biblioðece ("the Scriptures") from the Greek bibliotheke (lit. "book-repository" from biblion + theke, meaning "case, chest, or sheath"), used by Jerome and the common Latin word for it until Biblia began to displace it 9c. Use of the word in a figurative sense, as in "any authoritative book," is from 1804.

The Hebrew Bible

| Part of a series on |

| Judaism |

|---|

|

| Movements |

| Philosophy |

| Texts |

| Law |

|

Holy cities/places

|

| Important figures |

| Religious roles |

|

Culture and education

|

| Ritual objects |

| Prayers |

| Major holidays |

| Other religions |

| Related topics |

The Hebrew Bible (Hebrew: Template:Hebrew) is a term that refers to the common portions of the Jewish and Christian biblical canons. Its use is favored by some academic Biblical scholars as a neutral term that is preferred in academic writing both to "Old Testament" and to "Tanakh" (an acronym used commonly by Jews but unfamiliar to many English speakers and others) Template:Ref harvard.

"Hebrew" in "Hebrew Bible" may refer to either the Hebrew language or to the Hebrew people who historically used Hebrew as a spoken language, and have continuously used the language in prayer and study, or both.

Because "Hebrew Bible" refers to the common portions of the Jewish and Christian biblical canons, it does not encompass the deuterocanonical books (largely from the Koine Greek Septuagint translation (LXX), included in the canon of the Roman Catholic and Orthodox churches). Thus the term "Hebrew Bible" corresponds most fully to the Old Testament in use by Protestant denominations (adhering to Jerome's Hebraica veritas doctrine). Nevertheless, the term can be used accurately by all Christian denominations in general contexts, except where reference to specific translations or books is called for.

The Hebrew Bible consists of 39 books. Tanakh is an acronym for the three parts of the Hebrew Bible: the Torah ("Teaching/Law" also known as the Pentateuch), Nevi'im ("Prophets"), and Ketuvim ("Writings", or Hagiographa).

(see Table of books of Judeo-Christian Scripture)

Torah

Main article: TorahThe Torah, or "Teaching," is also known as the five books of Moses, thus Chumash or Pentateuch (Hebrew and Greek for "five," respectively).

The Pentateuch is composed of the following five books:

- I Genesis (Bereisheet בראשית),

- II Exodus (Shemot שמות),

- III Leviticus (Vayikra ויקרא),

- IV Numbers (Bemidbar במדבר), and

- V Deuteronomy (Devarim דברים)

The Hebrew book titles come from the first words in the respective texts. The Hebrew title for Numbers, however, comes from the fifth word of that text.

The Torah focuses on three moments in the changing relationship between God and people.

- The first eleven chapters of Genesis provide accounts of the creation (or ordering) of the world, and the history of God's early relationship with humanity.

- The remaining thirty-nine chapters of Genesis provide an account of God's covenant with the Hebrew patriarchs, Abraham, Isaac and Jacob (also called Israel), and Jacob's children (the "Children of Israel"), especially Joseph. It tells of how God commanded Abraham to leave his family and home in the city of Ur, eventually to settle in the land of Canaan, and how the Children of Israel later moved to Egypt.

- The remaining four books of the Torah tell the story of Moses, who lived hundreds of years after the patriarchs. His story coincides with the story of the liberation of the Children of Israel from slavery in Ancient Egypt, to the renewal of their covenant with God at Mount Sinai, and their wanderings in the desert until a new generation would be ready to enter the land of Canaan. The Torah ends with the death of Moses.

Traditionally, the Torah contains the 613 mitzvot, or commandments, of God, revealed during the passage from slavery in the land of Egypt to freedom in the land of Canaan. These commandments provide the basis for Halakha (Jewish religious law).

The Torah is divided into fifty-four portions which are read in turn in Jewish liturgy, from the beginning of Genesis to the end of Deuteronomy, each Sabbath. The cycle ends and recommences at the end of Sukkot, which is called Simchat Torah.

Nevi'im

Main article: Nevi'imThe Nevi'im, or "Prophets," tells the story of the rise of the Hebrew monarchy, its division into two kingdoms, and the prophets who, in God's name, judged the kings and the Children of Israel. It ends with the conquest of the Kingdom of Israel by the Assyrians and the conquest of the Kingdom of Judah by the Babylonians, and the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem. Portions of the prophetic books are read by Jews on the Sabbath (Shabbat). The Book of Jonah is read on Yom Kippur.

According to Jewish tradition, Nevi'im is divided into eight books. Contemporary translations subdivide these into seventeen books.

The eight books are:

- I. Joshua or Yehoshua

- II. Judges or Shoftim

- III. Samuel or Shmu'el (often divided into two books; Samuel may be considered the last of the judges or the first of the prophets, as his sons were named judges but were rejected by the Hebrew nation)

- IV. Kings or Melakhim (often divided into two books)

- V. Isaiah or Yeshayahu

- VI. Jeremiah or Yirmiyahu

- VII. Ezekiel or Yehezq'el

- VIII. Trei Asar (The Twelve Minor Prophets) תרי עשר

Ketuvim

Main article: KetuvimThe Ketuvim, or "Writings," may have been written during or after the Babylonian Exile but no one can be sure. According to Rabbinic tradition, many of the psalms in the book of Psalms are attributed to David; King Solomon is believed to have written Song of Songs in his youth, Proverbs at the prime of his life, and Ecclesiastes at old age; and the prophet Jeremiah is thought to have written Lamentations. The Book of Ruth is the only biblical book that centers entirely on a non-Jew. The book of Ruth tells the story of a non-Jew (specifically, a Moabite) who married a Jew and, upon his death, followed in the ways of the Jews; according to the Bible, she was the great-grandmother of King David. Five of the books, called "The Five Scrolls" (Megilot), are read on Jewish holidays: Song of Songs on Passover; the Book of Ruth on Shavuot; Lamentations on the Ninth of Av; Ecclesiastes on Sukkot; and the Book of Esther on Purim. Collectively, the Ketuvim contain lyrical poetry, philosophical reflections on life, and the stories of the prophets and other Jewish leaders during the Babylonian exile. It ends with the Persian decree allowing Jews to return to Jerusalem to rebuild the Temple.

Ketuvim contains eleven books:

- I. Tehillim (Psalms) תהלים

- II. Mishlei (Book of Proverbs) משלי

- III. 'Iyyov (Book of Job) איוב

- IV. Shir ha-Shirim (Song of Songs) שיר השירים

- V. Ruth (Book of Ruth) רות

- VI. Eikhah (Lamentations) איכה

- VII. Kohelet (Ecclesiastes) קהלת

- VIII. Esther (Book of Esther) אסתר

- IX. Daniel (Book of Daniel) דניאל

- X. Ezra (often divided into two books, Book of Ezra and Book of Nehemiah (עזרא (נחמיה

- XI. Divrei ha-Yamim (Chronicles, often divided into two books) דברי

הימים

Translations and editions

| This article does not cite any sources. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Bible" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (November 2006) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

The Tanakh was mainly written in Biblical Hebrew, with some portions (notably in Daniel and Ezra) in Aramaic.

Some time in the 2nd or 3rd century BC, the Torah was translated into Koine Greek, and over the next century, other books were translated (or composed) as well. This translation became known as the Septuagint and was widely used by Greek-speaking Jews, and later by Christians. It differs somewhat from the later standardized Hebrew (Masoretic Text). This translation was promoted by way of a legend that seventy separate translators all produced identical texts.

From the 800s to the 1400s, Jewish scholars today known as Karaites Masoretes compared the text of all known Biblical manuscripts in an effort to create a unified, standardized text. A series of highly similar texts eventually emerged, and any of these texts are known as Masoretic Texts (MT). The Masoretes also added vowel points (called niqqud) to the text, since the original text only contained consonant letters. This sometimes required the selection of an interpretation, since some words differ only in their vowels— their meaning can vary in accordance with the vowels chosen. In antiquity, variant Hebrew readings existed, some of which have survived in the Samaritan Pentateuch, the Dead Sea scrolls, and other ancient fragments, as well as being attested in ancient versions in other languages.

Versions of the Septuagint contain several passages and whole books beyond what was included in the Masoretic texts of the Tanakh. In some cases these additions were originally composed in Greek, while in other cases they are translations of Hebrew books or variants not present in the Masoretic texts. Recent discoveries have shown that more of the Septuagint additions have a Hebrew origin than was once thought. While there are no complete surviving manuscripts of the Hebrew texts on which the Septuagint was based, many scholars believe that they represent a different textual tradition ("vorlage") from the one that became the basis for the Masoretic texts.

Jews also produced non-literal translations or paraphrases known as targums, primarily in Aramaic. They frequently expanded on the text with additional details taken from Rabbinic oral tradition.

The two Torahs of Rabbinic Judaism

By the Hellenistic period of Jewish history, Jews were divided over the nature of the Torah. Some (for example, the Sadducees) believed that the Chumash contained the entire Torah, that is, the entire contents of what God revealed to Moses at Sinai and in the desert. Others, principally the Pharisees, believed that the Chumash represented only that portion of the revelation that had been written down (i.e., the Written Torah or the Written Law), but that the rest of God's revelation had been passed down orally (thus composing the Oral Law or Oral Torah). Orthodox and Masorti and Conservative Judaism state that the Talmud contains some of the Oral Torah. Reform Judaism also gives credence to the Talmud containing the Oral Torah, but, as with the written Torah, asserts that both were inspired by, but not dictated by, God.

The Old Testament

The Christian Old Testament, while having most or all books in common with the Jewish Tanakh, varies from Judaism in the emphasis it places and the interpretations it gives them. The books come in a slightly different order. In addition, some Christian groups recognize additional books as canonical members of the Old Testament, and they may use a different text as the canonical basis for translations.

Differing Christian usages of the Old Testament

The Septuagint (Greek translation, from Alexandria in Egypt under the Ptolemies) was generally abandoned in favor of the Masoretic text(~10th century CE)as the basis for translations of the Old Testament into Western languages from Saint Jerome's(347-420 CE)Vulgate to the present day. In Eastern Christianity, translations based on the Septuagint still prevail. Some modern Western translations make use of the Septuagint to clarify passages in the Masoretic text, where the Septuagint preserves an ancient understanding of the text. They also sometimes adopt variants that appear in texts discovered among the Dead Sea Scrolls.

A number of books which are part of the Greek Septuagint but are not found in the Rabbinic Hebrew Bible are often referred to as deuterocanonical books by Catholics referring to a later secondary (i.e. deutero) canonization. Most Protestants term these books as apocrypha while(confusingly) Catholic refer to those Septuagent books rejected from the Deuterocanon as Apcrypha as well. Evangelicals and those of the Modern Protestant traditions do not accept the deuterocanonical books as canonical, although Protestant Bibles included them until around the 1820s. However the Roman Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, and Oriental Orthodox Churches include these books as part of their Old Testament as all are derived from the Septuagint. The Catholic Church recognizes seven such books (Tobit, Judith, 1 Maccabees, 2 Maccabees, Wisdom of Solomon, Ecclesiasticus, and Baruch), as well as some passages in Esther and Daniel. Various Orthodox Churches include a few others, typically 3 Maccabees, Psalm 151, 1 Esdras, Odes, Psalms of Solomon, and occasionally 4 Maccabees.

St Jerome, while translating the Hebrew Scriptures(he was heavily influence by Rabbinic Judaism- residing his last 32 years in Bethlehem Palestine), questioned the deuterocanonicals inspiration and thus their application to doctrine and authority. He eventually, changed his position, and included them in the Vulgate though he did not translate the majority of the deuterocanonical books. In practice, Jerome, actually did utilized deuterocanon as inspired and authoritative as he writes in his book -Against the Pelagians: Dialogue Between Atticus, a Catholic, and Critobulus , a Heretic- (though he erroneously states the quote is from the Book of Wisdom, it accually is from the Book of Sirach, both of which are Deuterocanonical books):

"Your argument is ingenious, but you do not see THAT IT GOES AGAINST HOLY SCRIPTURE...(he begins quoting from Numbers 35:8, Ezekiel 18:23, and proceeds ) ... A. Do you expect me to explain the purposes and plans of God? The Book of Wisdom gives an answer to your foolish question: ‘Look not into things above thee, and search not things too mighty for thee.’(Sir 3:21) And elsewhere, ‘Make not thyself overwise, and argue not more than is fitting.’ And in the same place, ‘In wisdom and simplicity of heart seek God.’ You will perhaps deny the authority of this book....” (See see: http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/npnf206.I_1.html - last paragraphs.)

The New Testament

| Part of a series on | ||||

| Christianity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

|

||||

| Theology | ||||

|

||||

| Related topics | ||||

The Bible as used by the majority of english speaking Christians includes the Hebrew Scripture and the New Testament, which relates the life and teachings of Jesus, the letters of the Apostle Paul and other disciples to the early church and the Book of Revelation.

The New Testament is a collection of 27 books, produced by Christians, with Jesus as its central figure, written primarily in Koine Greek in the early Christian period. Nearly all Christians recognize the New Testament (as stated below) as canonical scripture. These books can be grouped into:

Original language

The New Testament was probably completely composed in Koine Greek, the language of the earliest manuscripts. Some scholars believe that parts of the Greek New Testament (in particular, the Gospel of Matthew) are actually a translation of an Aramaic or Hebrew original. Of these, a small number accept the Syriac Peshitta as representative of the original. See further Aramaic primacy.

Historic editions

Concerning ancient manuscripts, the three main textual traditions are sometimes called the Western text-type, the Alexandrian text-type, and Byzantine text-type. Together they compose the majority of New Testament manuscripts. There are also several ancient versions in other languages, most important of which are the Syriac (including the Peshitta and the Diatessaron gospel harmony), Ge'ez and the Latin (both the Vetus Latina and the Vulgate).

The earliest surviving complete manuscript of the entire Bible is the Codex Amiatinus, a Latin Vulgate edition produced in eighth century England at the double monastery of Wearmouth-Jarrow.

The earliest printed edition of the New Testament in Greek appeared in 1516 from the Froben press. It was compiled by Desiderius Erasmus on the basis of the few recent Greek manuscripts, all of Byzantine tradition, at his disposal, which he completed by translating from the Vulgate parts for which he did not have a Greek text. He produced four later editions of the text.

Erasmus was a Roman Catholic, but his preference for the textual tradition represented in Byzantine Greek text of the time rather than that in the Latin Vulgate led to him being viewed with suspicion by some authorities of his church.

The first edition with critical apparatus (variant readings in manuscripts) was produced by the printer Robert Estienne of Paris in 1550. The type of text printed in this edition and in those of Erasmus became known as the Textus Receptus (Latin for "received text"), a name given to it in the Elzevier edition of 1633, which termed it the text nunc ab omnibus receptum ("now received by all"). Upon it, the churches of the Protestant Reformation based their translations into vernacular languages, such as the King James Version.

The discovery of older manuscripts, such as the Codex Sinaiticus and the Codex Vaticanus, led scholars to revise their opinion of this text. Karl Lachmann’s critical edition of 1831, based on manuscripts dating from the fourth century and earlier, was intended primarily to demonstrate that the Textus Receptus must finally be corrected by the earlier texts. Later critical texts are based on further scholarly research and the finding of papyrus fragments, which date in some cases from within a few decades of the composition of the New Testament writings. It is on the basis of these that nearly all modern translations or revisions of older translations have been made, though some still prefer the Textus Receptus or the similar "Byzantine Majority Text".

Christian Theology

While individual books within the Christian Bible present narratives set in certain historical periods, most Christian denominations teach that the Bible itself has an overarching message.

There are among Christians wide differences of opinion as to how particular incidents as described in the Bible are to be interpreted and as to what meaning should be attached to various prophecies. However, Christians in general are in agreement as to the Bible's basic message. A general outline, as described by C.S. Lewis, is as follows:

- At some point in the past, mankind learned to depart from God's will and began to sin.

- Because no one is free from sin, humanity cannot deal with God directly, so God revealed Himself in ways people could understand.

- God called Abraham and his progeny to be the means for saving all of mankind.

- To this end, He gave the Law to Moses.

- The resulting nation of Israel went through cycles of sin and repentance, yet the prophets show an increasing understanding of the Law as a moral, not just a ceremonial, force.

- Jesus brought a perfect understanding of the Mosaic Law, that of love and salvation.

- By His death and resurrection, all who believe are saved and reconciled to God.

Many people who identify themselves as Christians, Muslims, or Jews regard the Bible as inspired by God yet written by a variety of imperfect men over thousands of years. Belief in sacred texts is attested to in Jewish antiquity, and this belief can also be seen in the earliest of Christian writings. Various texts of the Bible mention Divine agency in relation to prophetic writings, the most explicit being: 2 Timothy 3:16: "All scripture, inspired of God, is profitable to teach, to reprove, to correct, to instruct in justice." In their book A General Introduction to the Bible, Norman Geisler and William Nix wrote: "The process of inspiration is a mystery of the providence of God, but the result of this process is a verbal, plenary, inerrant, and authoritative record." Some Biblical scholars, particularly Evangelicals, associate inspiration with only the original text; for example some American Protestants adhere to the 1978 Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy which asserted that inspiration applied only to the autographic text of Scripture.

The canonization of the Bible

Main article: Biblical CanonCanonization of the Hebrew Bible

It has been theorized that canonical status of some books of the Hebrew Bible was still being discussed between 200 BCE and 100 CE, and that it had yet to reach definitive form. It is unclear at what point during this period the Jewish canon was fixed, though the Jewish canon which did eventually form did not include all the books found in the various editions of the Septuagint.

Canonization of the Old Testament and New Testament

The Old Testament canon entered into Christian use in the Greek Septuagint translations and original books, and their differing lists of texts. In addition to the Septuagint, Christianity subsequently added various writings that would become the New Testament. Somewhat different lists of accepted works continued to develop in antiquity. In the fourth century a series of synods produced a list of texts equal to the 27-book canon of the New Testament that would be subsequently used to today. Also c. 400, Jerome produced a definitive Latin edition of the Bible (see Vulgate), the canon of which, at the insistence of the Pope, was in accord with the earlier Synods. With the benefit of hindsight it can be said that this process effectively set the New Testament canon, although there are examples of other canonical lists in use after this time. A definitive list did not come from an Ecumenical Council until the Council of Trent (1545-1563).

During the Protestant Reformation, certain reformers proposed different canonical lists than what was currently in use. Though not without debate, the list of New Testament books would come to remain the same; however, the Old Testament texts present in the Septuagint, but not included in the Jewish canon, fell out of favour. In time they would come to be removed from most Protestant canons. Hence, in a Catholic context these texts are referred to as deuterocanonical books, whereas in a Protestant context they are referred to as Apocrypha, the label applied to all texts excluded from the Biblical canon. (Confusingly, Catholics and Protestants both describe certain other books, such as the ‘’Acts of Peter’’, as apocryphal).

Thus, the Protestant Old Testament of today has a 39-book canon—the number varies from that of the books in the Tanakh (though not in content) because of a different method of division—while the Catholic Church recognizes 46 books as part of the canonical Old Testament. The term “Hebrew Scriptures” is only synonymous with the Protestant Old Testament, not the Catholic, which contains the Hebrew Scriptures and additional texts. Both Catholics and Protestants have the same 27-book New Testament Canon.

Canonicity, which involves the discernment of which texts are divinely inspired, is distinct from questions of human authorship and the formation of the books of the Bible.

Bible versions and translations

In scholarly writing, ancient translations are frequently referred to as "versions", with the term "translation" being reserved for medieval or modern translations. Bible versions are discussed below, while Bible translations can be found on a separate page.

The original texts of the Tanakh were in Hebrew, although some portions were in Aramaic. In addition to the authoritative Masoretic Text, Jews still refer to the Septuagint, the translation of the Hebrew Bible into Greek, and the Targum Onkelos, an Aramaic version of the Bible.

The primary Biblical text for early Christians was the Septuagint or (LXX). In addition they translated the Hebrew Bible into several other languages. Translations were made into Syriac, Coptic, Ge'ez and Latin, among other languages. The Latin translations were historically the most important for the Church in the West, while the Greek-speaking East continued to use the Septuagint translation of the Old Testament and had no need to translate the New Testament.

The earliest Latin translation was the Old Latin text, or Vetus Latina, which, from internal evidence, seems to have been made by several authors over a period of time. It was based on the Septuagint, and thus included books not in the Hebrew Bible.

Pope Damasus I assembled the first list of books of the Bible at the Council of Rome in 382 A.D. He commissioned Saint Jerome to produce a reliable and consistent text by translating the original Greek and Hebrew texts into Latin. This translation became known as the Latin Vulgate Bible and was declared by the Church to be the only authentic and official Bible.

Bible translations for many languages have been made through the various influences of Catholicism, Orthodox, Protestant, etc especially since the Protestant Reformation. The Bible has seen a notably large number of English language translations.

The work of Bible translation continues, including by Christian organisations such as Wycliffe Bible Translators (wycliffe.net), New Tribes Missions (ntm.org) and the Bible Societies (biblesociety.org). Of the world's 6,900 languages, 2,400 have some or all of the Bible, 1,600 (spoken by more than a billion people) have translation underway, and some 2,500 (spoken by 270m people) are judged as needing translation to begin.

Differences in Bible Translations

- See also: Bible translations: Approaches.

As Hebrew and Greek, the original languages of the Bible, have idioms and concepts not easily translated, there is an on going critical tension about whether it is better to give a word for word translation or to give a translation that gives a parallel idiom in the target language. For instance, in the English language Catholic translation, the New American Bible, as well as the Protestant translations of the Christian Bible, translations like the King James Version, the New Revised Standard Version and the New American Standard Version are seen as literal translations (or "word for word"), whereas translations like the New International Version and New Living Version attempt to give relevant parallel idioms. The Living Bible and The Message are two paraphrases of the Bible that try to convey the original meaning in contemporary language. The further away one gets from word to word translation, the text becomes more readable while relying more on the theological, linguistic or cultural understanding of the translator, which one would not normally expect a lay reader to require.

Inclusive Language

Further, both Hebrew and Greek, like some of the Latin-origin languages, use the male gender of nouns and pronouns to refer to groups that contain both sexes. This creates some difficulty in determining whether a noun should be translated using terms that refer to men only, or men and women inclusively. Some translations avoid the issue by directly translating the word using male only terminology, whereas others try to use inclusive language where the translators believe it to be appropriate. Translations that attempt to use inclusive language are the New Revised Standard Version and the latest edition of the New International Version.

The introduction of chapters and verses

- Main article: Chapters and verses of the Bible; see Tanakh for the Jewish textual tradition.

The Hebrew Masoretic text contains verse endings as an important feature. According to the Talmudic tradition, the verse endings are of ancient origin. The Masoretic textual tradition also contains section endings called parashiyot, which are indicated by a space within a line (a "closed" section") or a new line beginning (an "open" section). The division of the text reflected in the parashiyot is usually thematic. The parashiyot are not numbered.

In early manuscripts (most importantly in Tiberian Masoretic manuscripts, such as the Aleppo codex) an "open" section may also be represented by a blank line, and a "closed" section by a new line that is slightly indented (the preceding line may also not be full). These latter conventions are no longer used in Torah scrolls and printed Hebrew Bibles. In this system the one rule differentiating "open" and "closed" sections is that "open" sections must always begin at the beginning of a new line, while "closed" sections never start at the beginning of a new line.

Another related feature of the Masoretic text is the division of the sedarim. This division is not thematic, but is almost entirely based upon the quantity of text.

The Byzantines also introduced a chapter division of sorts, called Kephalaia. It is not identical to the present chapters.

The current division of the Bible into chapters and the verse numbers within the chapters have no basis in any ancient textual tradition. Rather, they are medieval Christian inventions. They were later adopted by many Jews as well, as technical references within the Hebrew text. Such technical references became crucial to medieval rabbis in the historical context of forced debates with Christian clergy (who used the chapter and verse numbers), especially in late medieval Spain. Chapter divisions were first used by Jews in a 1330 manuscript, and for a printed edition in 1516. However, for the past generation, most Jewish editions of the complete Hebrew Bible have made a systematic effort to relegate chapter and verse numbers to the margins of the text.

The division of the Bible into chapters and verses has often elicited severe criticism from traditionalists and modern scholars alike. Critics charge that the text is often divided into chapters in an incoherent way, or at inappropriate rhetorical points, and that it encourages citing passages out of context, in effect turning the Bible into a kind of textual quarry for clerical citations. Nevertheless, the chapter divisions and verse numbers have become indispensable as technical references for Bible study.

Stephen Langton is reputed to have been the first to put the chapter divisions into a Vulgate edition of the Bible, in 1205. They were then inserted into Greek manuscripts of the New Testament in the 1400s. Robert Estienne (Robert Stephanus) was the first to number the verses within each chapter, his verse numbers entering printed editions in 1551 (New Testament) and 1571 (Hebrew Bible).

Advocacy of the Bible

Main articles: Advocacy of the Bible and Christian apologeticsChristian apologists advocate a high view of the Bible and sometimes advocate the doctrine of Biblical inerrancy.

Christian scholar Bernard Ramm is often quoted by conservative Christians for writing the following in his work Protestant Christian Evidences:

Jews preserved it as no other manuscript has ever been preserved. With their massora they kept tabs on every letter, syllable, word and paragraph. They had special classes of men within their culture whose sole duty was to preserve and transmit these documents with practically perfect fidelity — scribes, lawyers, massorettes.

In regard to the New Testament, there are about 13,000 manuscripts, complete and incomplete, in Greek and other languages, that have survived from antiquity.

A thousand times over, the death knell of the Bible has been sounded, the funeral procession formed, the inscription cut on the tombstone, and committal read. But somehow the corpse never stays put. No other book has been so chopped, knifed, sifted, scrutinized, and vilified. What book on philosophy or religion or psychology or belles lettres of classical or modern times has been subject to such a mass attack as the Bible? With such venom and skepticism? With such thoroughness and erudition? Upon every chapter, line and tenet?

Criticism of the Bible

- Main articles: Biblical criticism and Criticism of the Bible

Theologians and clerics, most notably Abraham Ibn Ezra, think that there are contradictions in the Bible. Benedict Spinoza concluded from a study of such contradictions that the Torah could not have had a single author, and thus, neither God nor Moses could be the authors of the Torah. By the 19th century, critical scholars, such as Hermann Gunkel and Julius Wellhausen argued that the various books of the Bible were written not by the presumed authors but by a heterogeneous set of authors over a long period. Although Biblical archeology has confirmed the existence of some of the people, places, and events mentioned in the Bible, many critical scholars have argued that the Bible be read not as an accurate historical document, but rather as a work of literature and theology that often draws on historical events — and often draws on non-Hebrew mythology — as primary source material. For these critics the Bible reveals much about the lives and times of its authors. Whether the ideas of these authors have any relevance to contemporary society is left to clerics and adherents of contemporary religions to decide.

The documentary hypothesis

Main article: Documentary hypothesisThe documentary hypothesis posits that the Pentateuch (written Torah) has its origins in sources who lived during the time of the United Monarchy or later, labeled J (Yahwists), E (Elohim), D (Deuteronomists), and P (Priests). These in turn are said to go back to oral traditions, drawing on (and sometimes parodying) earlier ancient Near Eastern mythology. Julius Wellhausen, who in the late 19th century gave this hypothesis a definitive formulation, suggested that these sources were edited together or redacted during the time of Ezra, perhaps by Ezra himself. Since that time Wellhausen's theory has been widely debated by critical scholars (e.g. Yehezkel Kaufman).

Trivia

- The In-N-Out fast food chain has hidden bible references on its foods packaging.

- John 3:16 is often parodied in wrestling and sports by its fans, with a favorite team or team members name, with 3:16, put on a sign held up when cheering.

- Family Guy references the bible in a similar manner, when Brian reads out loud a non existent line in the bible "And the lord said, Go Sox"

- Many manga or graphic novels are alternatively called Literary Bibles, with no connection to the Christian bible.

- The Japanese sometimes carry a different meaning for the word Bible (Baibaru), meaning a phrase that one takes to heart. This is notably mentioned in the Japanese pop song "Zankoku Na Tenshi no TE-ZE".

Notes and references

- Patrick H. Alexander The SBL Handbook of Style. Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson Publishers. ISBN 1-56563-487-X.

- "Reliability of Ancient Manuscripts". All About Truth.

- Online Etymology Dictionary entry for word "Bible"

- "From Hebrew Bible to Christian Bible" by Mark Hamilton on PBS's site From Jesus to Christ: The First Christians

- Dictionary.com etymology of the word "Bible"

- A Summary of the Bible by Lewis, C.S: Believer's Web

- See Philo of Alexandria, De vita Moysis 3.23; Josephus, Contra Apion 1.8

- "Basis for belief of Inspiration". Biblegateway.

-

Norman L. Geisler, William E. Nix (1986). A General Introduction to the Bible:p86. Moody Publishers. ISBN 0-8024-2916-5.

{{cite book}}: Check|authorlink=value (help); External link in|authorlink= - for example, seeLeroy Zuck, Roy B. Zuck (1991). Basic Bible Interpretation:p68. Chariot Victor Pub. ISBN 0-89693-819-0.

- Roy B. Zuck, Donald Campbell (2002). Basic Bible Interpretation. Victor. ISBN 0-7814-3877-2.

- Norman L. Geisler (1979, 1980). Inerrancy:p294. The Zondervan Corporation. ISBN 0-310-39281-0.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) -

International Council on Biblical Inerrancy (1978, ICBI.). "THE CHICAGO STATEMENT ON BIBLICAL INERRANCY" (pdf). International Council on Biblical Inerrancy.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - www.vision2025.org

- Chapters and Verses.

- The Examiner.

- See Bible references

- Berlin, Adele, Marc Zvi Brettler and Michael Fishbane. The Jewish Study Bible. Oxford University Press, 2003. ISBN 0-19-529751-2

- Anderson, Bernhard W. Understanding the Old Testament (ISBN 0-13-948399-3)

- Asimov, Isaac Asimov's Guide to the Bible, New York, NY: Avenel Books, 1981 (ISBN 0-517-34582-X)

- Dever, William G. Who Were the Early Israelites and Where Did they Come from? Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2003. ISBN 0-8028-0975-8.

- Ehrman, Bart D. Misquoting Jesus: The Story Behind Who Changed the Bible and Why New York, NY: HarperSanFrancisco, 2005. ISBN 0-06-073817-0.

- Geisler, Norman (editor), Inerrancy, Sponsored by the International Council on Biblical Inerrancy, Zondervan Publishing House, 1980, ISBN 0-310-39281-0.

- Head, Tom. The Absolute Beginner's Guide to the Bible. Indianapolis, IN: Que Publishing, 2005. ISBN 0-7897-3419-2.

- Hoffman, Joel M. In the Beginning. New York University Press. 2004. ISBN 0-8147-3690-4.

- Lindsell, Harold, The Battle for the Bible, Zondervan Publishing House, 1978, ISBN 0-310-27681-0.

- Lienhard, Joseph T. "The Bible, The Church, and Authority." Liturgical Press, Collegeville, Minnesota, 1995.

- Miller, John W. The Origins of the Bible: Rethinking Canon History Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press, 1994. ISBN 0-8091-3522-1.

- Riches, John. The Bible: A Very Short Introduction, Oxford University Press, 2000. ISBN 0-19-285343-0

- Finkelstein, Israel and Silberman, Neil A. The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology's New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2001. ISBN 0-684-86913-6.

- Taylor, Hawley O., "Mathematics and Prophecy," Modern Science and Christian Faith, Wheaton,: Van Kampen, 1948, pp.175-183.

- Wycliffe Bible Encyclopedia, subject: prophecy, page 1410, Moody Bible Press, Chicago, 1986

- Wycliffe Bible Encyclopedia, subject: Book of Ezekiel, page 580, Moody Bible Press, Chicago, 1986

- On gender neutrality. gender-neutral Bible translations.

See also

Biblical analysis

- Books of the Bible

- Table of books of Judeo-Christian Scripture

- Bible translations

- Biblical canon

- Bible prophecy

- Bible chronology

- Ten Commandments

- Ritual Decalogue

- New Testament view on Jesus' life

- Lost books of the Old Testament

- Lost books of the New Testament

- Parsha

Perspectives on the Bible

History and the Bible

Biblical scholarship and analysis

- Biblical archaeology

- Dating the Bible

- Bible conspiracy theory

- Biblical inerrancy

- Advocacy of the Bible

- Internal consistency and the Bible

- Bible scientific foreknowledge

- Criticism of the Bible

- Animals in the Bible

- Bibliolatry

External links

Bible Societies and Translations

- American Bible Society

- United Bible Society

- The International Bible Society (New York/Colorado Springs)

- World Bible Translation Center

- Wycliffe Bible Translators

- The Concordant Version

Bible texts

Hebrew

- Hebrew-English Bible (JPS 1917 translation; includes Hebrew audio)

- XML Hebrew-English (KJV) Bible

- Old Testament in Hebrew

Greek

- See "External Links" under Septuagint and New Testament.

Latin

- Latin Vulgate - Latin Vulgate with parallel Douay-Rheims and King James English translations

- SacredBible.org - Latin Vulgate translation of the Bible

- Jerome's Latin Vulgate (405 A.D.)

English

- AudioBible — Audio version of the King James Version.

- Blue Letter Bible — On-line interactive reference library continuously updated from the teachings and commentaries of selected pastors and teachers who hold to the conservative, historical Christian faith.

- E-sword — Downloadable Bible in many different versions, for MS Windows.

- American Standard Version.

- English Standard Version from Good News/Crossway (the publisher).

- King James Version with dictionary.

- King James Version.

- New Revised Standard Version.

- New World Translation of the Holy Scriptures.

- World English Bible.

- LDS King James Version with audio, extensive commentary and cross-references.

- King James Version built using AJAX technologies, with Strongs and Greek Morphological Codes by Robinson.

Turkish

- Turkish Bible (Turkish Old and New Testament)

Others

- The Hypertext Bible with side-by-side translations in English, Latin, Greek, and Hebrew at the Internet Sacred Text Archive

- Bible Gateway at GospelCom.net text search in any one of many translations/languages, or lookup complete passages in up to five different translations/languages at once. Select from among NIV, NASB, MSG, AMP, NLT, KJV, ESV, CEV, NKJV, ASV, NLV, NIrV and many others.

- Bible Read-Through - read through the Bible aid that has a standard one year read through as well as the ability to design your own read through.

- TheFreeBible.com provides free Bible software downloads

- Interlinear (word-by-word) translation of the Christian Bible from the original Hebrew and Koine Greek

- Aramaic New Testament resources

- Over 40 versions of the Bible

- Eastern and Western Armenian Bible

- Online Bible (King James Version & Old Testament)

- Bible - Louis Segond de 1910

- Spanish Bible PDT version

- Complete Sayings of Christ (long download)

- Crosswalk.com Parallel Bible to see two versions side by side, any of NAS, ASV, ESV, NKJV, KJV, NLT, NRS, GNT, WEB, MSG, NIV, NIrV and many others.

- Blue Letter Bible provides resources on a verse by verse basis, such as commentaries, definitions, concordance with Hebrew/Greek, related information and parallel bible on the one selected verse in KJV, NKJV, NLT, NIV, ESV, NASB, RSV, ASV and others.

- American Bible Society to search NASB, KJV, CEV, ASV and others.

- University of Virginia Library for word proximity searches on the KJV bible.

- Many translations in English, verse by verse

Commentaries

- Biblical History, The Jewish History Resource Center — Project of the Dinur Center for Research in Jewish History, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

- Judaica Press Translation — Online Jewish translation of the books of the Bible. Includes the Tanakh and Rashi's entire commentary.

- Reading and Understanding the Bible.

- Source for Bible Answers.

- Amazing Facts Bible Studies.

- The Skeptic's Annotated Bible.

- Learning Bible Today – An historical approach the Bible.

- Biblical Errancy and Contradictions.

- John Gill's Exposition of the Bible — Verse by verse commentary.

- Matthew Henry's Commentary on the Whole Bible — Unabridged.