This is an old revision of this page, as edited by 115.66.26.19 (talk) at 22:13, 4 May 2023 (Fixed errors). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 22:13, 4 May 2023 by 115.66.26.19 (talk) (Fixed errors)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)This article is about the Babylonian prince. For other uses, see Belshazzar (disambiguation). Not to be confused with Belteshazzar.

Crown prince of Babylon

| Belshazzar | |

|---|---|

| Crown prince of Babylon | |

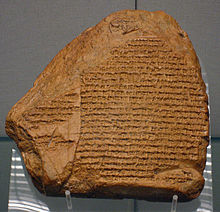

The Nabonidus Chronicle, an ancient Babylonian text which chronicles the reign of Belshazzar's father and also documents the period during which Belshazzar was regent in Babylon The Nabonidus Chronicle, an ancient Babylonian text which chronicles the reign of Belshazzar's father and also documents the period during which Belshazzar was regent in Babylon | |

| Died | 12 October 539 BC (?) Babylon (?) |

| Akkadian | Bēl-šar-uṣur |

| Dynasty | Chaldean dynasty (matrilineal) (?) |

| Father | Nabonidus |

| Mother | Nitocris (?) (A daughter of Nebuchadnezzar II) (?) |

Belshazzar (Babylonian cuneiform: ![]() Bēl-šar-uṣur, meaning "Bel, protect the king"; Template:Lang-he Bēlšaʾṣṣar) was the son and crown prince of Nabonidus (r. 556–539 BC), the last king of the Neo-Babylonian Empire. Through his mother, he might have been a grandson of Nebuchadnezzar II (r. 605–562 BC), though this is not certain and the claims to kinship with Nebuchadnezzar may have originated from royal propaganda.

Bēl-šar-uṣur, meaning "Bel, protect the king"; Template:Lang-he Bēlšaʾṣṣar) was the son and crown prince of Nabonidus (r. 556–539 BC), the last king of the Neo-Babylonian Empire. Through his mother, he might have been a grandson of Nebuchadnezzar II (r. 605–562 BC), though this is not certain and the claims to kinship with Nebuchadnezzar may have originated from royal propaganda.

Belshazzar played a pivotal role in the coup d'état that overthrew the king Labashi-Marduk (r. 556 BC) and brought Nabonidus to power in 556 BC. Since Belshazzar was the main beneficiary of the coup, through confiscating and inheriting Labashi-Marduk's estates and wealth, it is likely that he was the chief orchestrator. Through proclaiming his father as the new king, Belshazzar also made himself the first-in-line to the throne. As Nabonidus was relatively old at the time, Belshazzar could expect to become king within a few years.

Nabonidus was absent from Babylon from 553 BC to 543 or 542 BC, in self-imposed "exile" at Tayma in Arabia, for unknown reasons. For the duration of the decade-long absence of his father, Belshazzar served as regent in Babylon. Belshazzar was entrusted with many typically royal prerogatives, such as granting privileges, commanding portions of the army, and receiving offerings and oaths, though he continued to be styled as the crown prince (mār šarri, literally meaning "son of the king"), never assuming the title of king (šarru). Belshazzar also lacked many of the prerogatives of kingship, most importantly he was not allowed to preside over and officiate the Babylonian New Year's festival, which was the exclusive right of the king himself. Belshazzar's fate is not known, but is often assumed that he was killed during Cyrus the Great's Persian invasion of Babylonia in 539 BC, presumably at the fall of the capital Babylon on 12 October 539 BC.

Belshazzar appears as a central character in the story of Belshazzar's feast in the Biblical Book of Daniel, recognized by scholars as a work of historical fiction. and several details are not consistent with historical facts. Belshazzar is portrayed as the king of Babylon and "son" of Nebuchadnezzar, though he was actually the son of Nabonidus—one of Nebuchadnezzar's successors—and he never became king in his own right, nor did he lead the religious festivals as the king was required to do. In the story, the conqueror who inherits Babylon is Darius the Mede, but no such individual is known to history, and the invaders were actually Persians. This is typical of the "tale of court contest" in which historical accuracy is not an essential element.

Portrayal in later Jewish tradition

In the Book of Daniel, Belshazzar is not malevolent (he rewards Daniel and raises him to high office). The later authors of the Talmud and the Midrash emphasize the tyrannous oppression of his Jewish subjects, with several passages in the Prophets interpreted as referring to him and his predecessors. For example, in the passage, "As if a man did flee from a lion, and a bear met him" (Amos 5:19), the lion is said to represent Nebuchadnezzar, and the bear, equally ferocious if not equally courageous, is Belshazzar. The Babylonian kings are often mentioned together as forming a succession of impious and tyrannical monarchs who oppressed Israel and were therefore foredoomed to disgrace and destruction. Isaiah 14:22, "And I will rise up against them, saith the Lord of hosts, and cut off from Babylon name and remnant and son and grandchild, saith the Lord", is applied to the trio: "Name" to Nebuchadnezzar, "remnant" to Amel-Marduk, "son" to Belshazzar, and "grandchild" Vashti (ib.). The command given to Abraham to cut in pieces three heifers (Genesis 15:9) as a part of the covenant established between him and his God was thus elucidated as symbolizing Babylonia, which gave rise to three kings, Nebuchadnezzar, Amel-Marduk, and Belshazzar, whose doom is prefigured by this act of "cutting to pieces" (Midrash Genesis Rabbah xliv.).

The Midrash literature enters into the details of Belshazzar's death. Thus the later tradition states that Cyrus and Darius were employed as doorkeepers of the royal palace. Belshazzar, being greatly alarmed at the mysterious handwriting on the wall, and apprehending that someone in disguise might enter the palace with murderous intent, ordered his doorkeepers to behead anyone who attempted to force an entrance that night, even though such person should claim to be the king himself. Belshazzar, overcome by sickness, left the palace unobserved during the night through a rear exit. On his return, the doorkeepers refused to admit him. In vain did he pled that he was the king. They said, "Has not the king ordered us to put to death anyone who attempts to enter the palace, though he claims to be the king himself?" Suiting the action to the word, Cyrus and Darius grasped a heavy ornament forming part of a candelabrum, and with it shattered the skull of their royal master (Shir ha-Shirim Rabbah 3:4).

See also

- Cylinders of Nabonidus

- Cultural depictions of Belshazzar

- List of biblical figures identified in extra-biblical sources

References

- Chavalas 2000, p. 164.

- Glassner 2004, p. 232.

- Shea 1988, p. 75.

- Collins 1984, p. 41.

- ^ Laughlin 1990, p. 95.

- ^ Seow 2003, pp. 4–6.

- Collins 2002, p. 2.

- Collins 1984, p. 41,67.

- Seow 2003, p. 7.

- ^

Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). "Belshazzar". The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). "Belshazzar". The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

Bibliography

- Albertz, Rainer (2003). Israel in Exile: The History and Literature of the Sixth Century B.C.E. Society of Biblical Literature. ISBN 9781589830554.

- Beaulieu, Paul-Alain (1989). Reign of Nabonidus, King of Babylon (556-539 BC). Yale University Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctt2250wnt. ISBN 9780300043143. JSTOR j.ctt2250wnt. OCLC 20391775.

- Beaulieu, Paul-Alain (2006). "Berossus on Late Babylonian History". Oriental Studies (Special Issue: A Collection of Papers on Ancient Civilizations of Western Asia, Asia Minor and North Africa): 116–149.

- Briant, Pierre (2002). From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 9781575061207.

- Chavalas, Mark W. (2000). "Belshazzar". In Freedman, David Noel; Myers, Allen C. (eds.). Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9789053565032.

- Collins, John J. (1984). Daniel: With an Introduction to Apocalyptic Literature. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802800206.

- Collins, John J. (2002). "Current Issues in the Study of Daniel". In Collins, John J.; Flint, Peter W.; VanEpps, Cameron (eds.). The Book of Daniel: Composition and Reception. Vol. I. BRILL. ISBN 978-0391041271.

- Dougherty, Raymond Philip (1929). Nabonidus and Belshazzar. Wipf and Stock Publishers (2008 reprint). ISBN 9781556359569.

- Glassner, Jean-Jacques (2004). Mesopotamian Chronicles. Society of Biblical Literature. ISBN 9781589830905.

- Henze, M.H. (1999). The Madness of King Nebuchadnezzar. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-9004114210.

- Laughlin, John C. (1990). "Belshazzar". In Mills, Watson E.; Bullard, Roger Aubrey (eds.). Mercer Dictionary of the Bible. Mercer University Press. ISBN 9780865543737.

- Newsom, Carol A.; Breed, Brennan W. (2014). Daniel: A Commentary. Presbyterian Publishing Corp. ISBN 9780664220808.

- Seow, C.L. (2003). Daniel. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664256753.

- Shea, William H. (1982). "Nabonidus, Belshazzar, and the Book of Daniel: an Update". Andrews University Seminary Studies. 20 (2): 133–149.

- Shea, William H. (1988). "Bel(te)shazzar Meets Belshazzar". Andrews University Seminary Studies. 26 (1): 67–81.

- Waters, Matt (2014). Ancient Persia: A Concise History of the Achaemenid Empire, 550–330 BCE. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107652729.

- Weiershäuser, Frauke; Novotny, Jamie (2020). The Royal Inscriptions of Amēl-Marduk (561–560 BC), Neriglissar (559–556 BC), and Nabonidus (555–539 BC), Kings of Babylon (PDF). Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1646021079.

- Wiseman, Donald J. (2003) . "Babylonia 605–539 B.C.". In Boardman, John; Edwards, I. E. S.; Hammond, N. G. L.; Sollberger, E.; Walker, C. B. F. (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History: III Part 2: The Assyrian and Babylonian Empires and Other States of the Near East, from the Eighth to the Sixth Centuries B.C. (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-22717-8.

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). "Belshazzar". The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). "Belshazzar". The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

| Book of Daniel | |

|---|---|

| Bible chapters | |

| Additions | |

| Places | |

| People | |

| Angels | |

| Terms | |

| Christian interpretations | |

| Manuscripts | |

| Sources | |