This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Thatother1dude (talk | contribs) at 13:50, 9 April 2007 (→Ironclads in fiction). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 13:50, 9 April 2007 by Thatother1dude (talk | contribs) (→Ironclads in fiction)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) "Ironclad" redirects here. For other uses, see Ironclad (disambiguation) For pre-modern armoured ships, see Pre-industrial armoured ships.

The ironclad warship (or simply ironclad) was a type of warship developed in Europe and the United States during the mid-19th Century, its chief characteristics being iron (or later steel) protective armour, steam propulsion and powerful shell-firing (self encased ammunition) guns.

The development of the ironclad meant the end of the wooden ship of the line and ushered in a period of experimentation and development, leading to the pre-Dreadnought battleship and the armoured cruiser.

The development of ironclads revolutionised naval warfare, and introduced huge diversity into warship design. Naval terminology struggled to keep up with the pace of technological change: when HMS Warrior was launched, she was rated merely as a frigate, in spite of being more powerful than any ship-of-the-line. . Throughout the century new terms for warships were developed, including adaptations of existing classes (armoured frigate, armoured corvette); descriptions based on armament (turret ship, centre-battery ship, armoured ram); or on particularly famous examples of a type (e.g. monitor). The Royal Navy added further confusion in the 1880s by re-classifying the Warrior as a battleship, reflecting the late-19th Century vocabulary of battleships and cruisers.

Origins of the Ironclad

According to naval historian R.D. Hill, "the (ironclad) had three chief characteristics: a metal-skinned hull, steam propulsion and a main armament of guns capable of firing explosive shells. It is only when all three characteristics are present that a fighting ship can properly be called an ironclad". Until the end of the 1840s, the sailing ship of the line, a large wooden warship mounting over a hundred guns and carronades, continued to hold the dominant position in naval combat which it had occupied since the 17th century. Within twenty years the series of developments made these ships obsolete.

Steam ships-of-the-line

The first major change to the ship of the line was the introduction of steam power as an auxiliary propulsion system.

The first military uses of steamships came in the 1810s, and in the 1820s a number of navies experimented with paddle steamer warships. Their use spread in the 1830s, with paddle–steamer warships participating in conflicts like the First Opium War alongside ships of the line and frigates.

Paddle steamers, however, had major disadvantages. The paddle–wheel above the waterline was exposed to enemy fire, while itself preventing the ship for firing broadside effectively. During the 1840s, the screw propellor emerged as the most likely method of steam propulsion, with both Britain and the USA launching screw-propelled warships in 1843. Through the 1840s, the British and French navies launched increasingly larger and more powerful screw ships, alongside sail-powered ships of the line. In 1845, Viscount Palmerston gave an indication of the role of the new steamships in tense Anglo-French relations, describing the English Channel as a "steam bridge", rather than a barrier to French invasion. It was partly because of the fear of war with France that the Royal Navy converted several old 74–gun ships of the line into 60-gun steam-powered defensive harbour batteries, called blockships, starting in 1845.

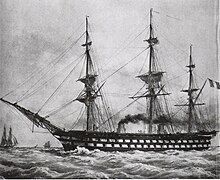

The French Navy, however, developed the first purpose-built steam battleship, with the 90–gun Le Napoléon in 1850. She is also considered the first true steam battleship, and the first screw battleship ever. Napoleon was armed as a conventional ship-of-the-line, but her steam engines could give her a speed of 12 knots, regardless of the wind conditions: a potentially decisive advantage in a naval engagement.

Eight sister-ships to Le Napoléon were built in France over a period of ten years, as the United Kingdom soon managed to take the lead in production, in number of both purpose-built and converted units. Altogether, France built 10 new wooden steam battleships and converted 28 from older battleship units, while the United Kingdom built 18 and converted 41.

Usually a wooden warship had to be constructed over several years, in order to allow the timber to season properly. By the end of the 1850s, the naval rivalry between the British and French navies led to speed-up ship building programmes. This forced the shipmakers to either rebuild older ships into steam vessels or to use unseasoned timber to keep up with the demand. Another significant cost increasing factor was the ceasing of timber deliveries from Russia with the Crimean War. Unseasoned timber and damp from steam engines would also provide the ideal environment for rot. This and the large amounts of timber needed for the fleet programmes made the iron-hulled ships cheaper to build and maintain.

Shells and Red-Hot Shot

The reign of the unarmored wooden ship-of-the-line was short. During the 1850s, changes in the armament of wooden steam warships made the adoption of iron armor a necessity.

It is commonly thought that the adoption of iron armor was forced by the introduction of Paixhans guns — weapons which could fire an explosive shell over a flat trajectory. The first such guns were produced in 1841 and France, the United Kingdom, Russia and the United States adopted the new naval guns in the 1840s. (Paixhans himself, a French artillery officer of the beginning of the 19th century, was a naval theorist claiming that a few aggressively armed small units could destroy the largest naval units of the time, making him a precursor of the French Jeune Ecole school of thought.)

However, this was not the only change in armament to the disadvantage of wooden ships. Existing naval cannon were increasingly adopted to fire red-hot shot, which could lodge in the hull of a wooden ship and cause a fire or ammunition explosion. Some navies even experimented with hollow shot filled with molten metal for extra incendiary power. These types of heated shot had the advantage over shells that they did not require fuses, which remained unreliable in shell guns for some time.

Exactly which of these developments was more responsible for the end of the wooden battlefleet is a matter of debate. The ease with which the shell guns of the Russian Black Sea Fleet annihilated the Turkish fleet at the Battle of Sinop in 1853 is often cited as the end of the wooden navy; however, other observers have argued that after six hours of firing a similar result would have been achieved with solid shot. More British and French casualties were caused in the Crimean War by red-hot shot fired from Russian forts than by explosive shells.

During the war, the French and British navies collaborated on the design of armoured floating batteries for reducing Russian defenses which had previously held off attempts at bombardment by wooden hulled battleships. The batteries were essentially mastless barges plated in iron which were towed into position prior to engaging the enemy. The French used theirs in 1855 against the defenses at Kinburn on the Black Sea. The British were delayed in bringing their batteries to the Baltic Sea to use against Kronstadt in 1856 and the war ended before they were used. But the brief success of the floating ironclad battery at Crimea convinced both Britain and France to begin construction of the first self-propelled ironclad warships.

The first ironclads

The first ocean-going ironclad warship was the French La Gloire of 1859. Her wooden hull was protected by a layer of thick iron armour 4.5 inches thick, and she was armed with fifty guns firing broadside. She propelled by a steam engine, driving a single screw propeller for a speed of 13 knots, far faster than could be achieved under sail.

La Gloire would spark a mini-arms race when Britain constructed and launched the steam frigate Warrior in 1860, Britain's first ironclad warship. France proceeded to construct 16 ironclad warships, including two more sister ships to La Gloire, and the only two-decked broadside ironclads ever built, the Magenta and the Solferino, which were also the first warships to be equipped with a spur ram.

The inefficiency of steam engines at the time, and the need for frequent coaling, limited the range of most ships under steam, and for a long time sails were still required for global reach. Many early ironclads, like Warrior had retractable screws to reduce drag while under sail; though in practice the steam engine was run at a low throttle when cruising under sail (the last British ship to be so equipped was HMS Shannon (1875), which remained in service until 1899).

Armament

For much of the ironclad age the consequences of technology on tactics were unclear. While the first ironclads were broadside-armed like their ship-of-the-line predecessors, the influence of ramming tactics and improvements in guns resulted in a diverse set of armaments.

The Ram versus the Gun

In the mid 19th Century, some naval designers believed that, with steam power freeing ships from the wind, and armour making them invulnerable to shellfire, the ram was again the most important weapon in naval warfare, as it had been in the days of galleys, and a range of ships were built as 'armoured rams'. Examples include the British-built Peruvian vessel Huascar

The idea held influence for much of the 19th century. Rams like CSS Virginia, USS General Price and CSS Manassas engaged in the American Civil War with limited success. However, this failure gave less influence on European ship design than the spectacular but lucky success of the Austrian flagship Ferdinand Max sinking the Italian Re d'Italia with a ramming action at the Battle of Lissa in 1866.. In the Royal Navy, George Sartorious was impressed enough that he campaigned for the ram to be made the principal weapon of naval combat. While his campaign was unsuccessful, the RN was building ships designed for ramming as late as HMS Hero of 1885.

Development of naval guns

In addition to the afore-mentioned Paixhans guns, improvements in metallurgy and design, with the adoption of rifling, meant ever more powerful guns could be fitted to ironclads. The transition from smoothbore cannon to Rifled Muzzle Loaders and then to Rifled Breech Loaders greatly affected the design of naval vessels.

From 1854, the American John A. Dahlgren, took the Paixhans gun, which was designed only for a shell, to develop a gun capable of firing shot and shell, and these were used during the American Civil War (1861-1865), for instance on USS Monitor.

Rifled Muzzle-Loaders

It was well known that a rifled gun offered greater accuracy and long range. HMS Warrior was equipped with a mixture of smoothbore guns and Armstrong Guns, which were rifled muzzle loaders. The Royal Navy continued with RML-type guns into the 1880s: HMS Inflexible used them in the bombardment of Alexandria in 1882. Muzzle-loading rifles had the disadvantage that the barrel had to be retracted inside the ship before reloading, reducing their rate of fire. They were also at the risk of explosion from double loading.

Breech-loading Rifles

The slowness of the rifled muzzle-loader could be overcome by loading from the breech. The French pioneered the way with the 13.4in Model 1870, the first naval rifled breech loader but it took until the 1890s for the Royal Navy to adopt this type of weapon.

Improvements in powder

Black powder expanded rapidly after combustion, therefore efficient cannons had relatively short barrels, otherwise the friction of the barrel would slow down the shell after the expansion was complete. The sharpness of the black powder explosion also meant that guns were subjected to extreme material stress. One important step was to press the powder into pellets. This kept the ingredients from separating and allowed some control of combustion by choosing the pellet size. Brown powder (black powder, incorporating charcoal that was only partially carbonized) combusted less rapidly, which allowed longer barrels, thus allowing greater accuracy. It also put less stress on the insides of the barrel, allowing guns to last longer and to be manufactured to tighter tolerances.

The development of smokeless powder by the French inventor Paul Vielle in 1884 was a critical influence in the evolution of the modern battleship. Eliminating the smoke greatly enhanced visibility during battle. The energy content, thus the propulsion, is much greater than that of black powder, and the rate of combustion can be controlled by adjusting the mixture. Smokeless powder also resists detonation and is much less corrosive.

Positioning of Armament

If the main weapon was to be a gun, there was question about where to place them. More modern guns were more powerful and heavier in weight, which together with the weight of armour plating meant ships could carry fewer of them. A number of experiments were made to get the best positioning of guns for their field of fire. The traditional broadside armament was ill-suited to the heavier guns, because each gun was very limited in its field of fire, particularly ahead and astern - the most important directions to close the range, and particularly for ships designed with ramming in mind.

Centre-Battery

Another option was the centre-battery, in which the armament was placed at the centre of the ship in an armoured citadel. The first centre-battery ship was HMS Bellerophon of 1865. The concentration of armament amidships mean the ship could be shorter and handier than a broadside type like Warrior. The disadvantage of the centre-battery was that, while more flexible than the broadside, each gun still had a relatively restricted field of fire and few guns could fire directly ahead.

Turrets

Turrets, following the designs of John Ericsson and British inventor Captain Cowper Coles helped to solve the problem. The turret also meant that a ship no longer had to turn on the beam in order to bring the greatest number of guns to bear on a target; the turret itself was turned toward the target independent of the ship's course. By allowing an arc of fire, turrets increased the potential of a relatively small number of guns, and allowed greater calibers for the same total weight and field of fire.

The turret concept became popular after the engagement of the USS Monitor in 1861. An improved version of the turret, with the weight borne on rollers around the outside of the turret rather than on a central stalk, was introduced by Coles in the Danish warship Rolf Krake and in the converted Royal Sovereign. However, turrets were not without problems: they demanded an unobstructed field of fire, which sat badly with the need for a full sailing rig. HMS Captain, designed by Coles as an example of how this circle could be squared, capsized in 1870. Monarch managed to survive, but was still restricted to firing from her turrets only on the port and starboard beams.

U.S. Civil War

Ironclads reached their full potential during the U.S. Civil War. As soon as the states that formed the Confederacy broke away from the Union, one of the first acts of the new Confederate secretary of the navy, Stephen Mallory, was to transform the few warships the Confederacy had into ironclads, despite only one foundry (Tredegar Iron Works, Richmond, Virginia) capable of making iron plate in any quantity. The first of these vessels to see action was CSS Manassas, a turtleback ironclad ram formerly known as the steam-tug Enoch Train. She was used in combat in October 1861 against the U.S. Navy and initially proved somewhat effective until U.S. ships learned to exploit her rather weak armor. Another advantage which Mallory was quick to exploit was the former U.S. Navy yard at Norfolk, Virginia, of which the fleeing Federals had failed to completely destroy at the start of the war in 1861, leaving behind guns, ammunition, stores, and a drydock which would be put to use when they raised one of the vessels sunk: the steam frigate USS Merrimack.

James Eads' gunboats

A riverboat captain, James Buchanan Eads, proposed to the Union government a fleet of ironclad riverboats, which essentially were civilian riverboats stripped down of their superstructures and covered with an iron-plated casemate protecting the paddlewheel and housing a dozen guns; he would further impress the government by producing 8 of these ships within 100 days. Also known as City-Class ironclads (each vessel was re-named for a city during the conversion), all of these vessels served effectively on the major rivers during the Civil War, either as support for land troops or in individual battles of their own right.

Other proposals

President Abraham Lincoln had received other designs on ironclad warships which could be contracted out for building and service in the United States Navy. One of these was a large steam frigate bearing 18 guns and plated over with six inches of iron; she would be named New Ironsides. The second was a smaller ship, the thinly-armoured USS Galena. A third design would reach Lincoln only after the designer, Swedish inventor John Ericsson, a man who hated the Navy after he was scapegoated following a gun accident onboard USS Princeton, was talked into going before the design board bearing his model of a strange little craft he called the Monitor.

The Monitor and the Merrimack

The Battle of Hampton Roads began on March 8, 1862, when the Merrimack, raised and repaired, steamed out of the former Norfolk Navy Yard to her new life as CSS Virginia, her masts and main deck removed and replaced with a sloping, iron-armoured casemate bearing 22 guns. Virginia steamed toward the blockading Union fleet, ramming and sinking USS Cumberland, setting fire to USS Congress, and causing a third, USS Minnesota, to run aground as it tried to flee. The following day as Virginia returned to finish the battle, the Union ironclad USS Monitor was waiting, setting the stage for a four-hour battle that has since become legend. Although inconclusive, the news of the battle reverberated world-wide, pointing out the stark fact that every other naval warship was rendered obsolete.

The Battle of Hampton Roads, and the later engagements, proved that warship design had irrevocably changed. Monitor, with its rotating turret and extremely low profile, was a revolutionary design for a warship. The U.S. built a number of "monitor-class ships", as they became known; they had engaged in battles during the Civil War with Confederate ironclads which followed the casemate design of the Virginia. The use of monitor ships spread quickly throughout the world after the war. John Ericsson, the designer of the Monitor, returned to his native Sweden and constructed similar ships for the Swedish Navy.

For the rest of the Civil War, the Union attempted to blockade the Confederacy, while Southern ships attempted to slip the blockade and to inderdict the Union's commerce. Monitor-type vessels played an important role in the blockade, though they were often too slow and too unseaworthy to be able to pursue blockade-runners. Ironclads also played a part in the battle for dominance of America's rivers. The Confederate ram CSS Albemarle, a fearsome warship in its own right (having been armoured with discarded railroad ties), had the distinction of being the first vessel sunk by a torpedo in October 1864 while struggling for control of the Roanoake river.

Ironclads were deployed by the Union for naval attacks on Southern ports. Seven Union monitors, including USS Montauk, participated in the failed attack on Charleston, South Carolina; one was sunk. Two small ironclads, CSS Palmetto State and CSS Chicora participated in the defence of the harbour. For the later attack Mobile Bay, the Union assembled four monitors as well as eleven wooden ships, facing the Tennessee, the Confederacy's most powerful ironclad.

Other Ironclad engagements

While ironclads spread rapidly in navies worldwide, there were few pitched naval battles involving ironclads. For most of the 19th century, there were few naval conflicts. Most European nations settled differences on land, and the Royal Navy dominated the sea to the extent that no rival power could take Britain on. The naval engagements involving ironclads normally involved second-rate naval powers.

Chincha Islands War

Both sides used ironclads in the Chincha Islands War between Spain and Chile and Peru in the early 1860s. The powerful Spanish Numancia was instrumental in destroying the fortress at El Callao in the Battle of Callao. However, Peru was able to deploy two Richmond-class monitors based on American Civil War Designs, the Loa and the Victoria, as well as two British-built ironclads; Independencia, a centre-battery ship, and the turret ship Huáscar.

Numancia was the first ironclad to circumnavigate the world (arriving in Cádiz on September 20, 1867, and earning the motto: "Enloricata navis que primo terram circuivit").

Battle of Lissa

The largest battle involving ironclads was the battle of Lissa, in 1866. Waged between the Austro-Hungarian and Italian navies, the battle pitted combined fleets of wooden frigates and corvettes and ironclad warships on both sides in the largest European naval battle since the Battle of Trafalgar. The superior Italian fleet lost its two most powerful ironclads, Re d'Italia and Affondatore, while the Austrian wooden-built Kaiser remarkably survived close actions with four Italian ironclads. The battle ensured the popularity of the ram as a weapon in European ironclads for many years, and the victory won by Austria-Hungary established it briefly as the predominant naval power in the Adriatic.

Boshin war (Japan)

During the 1868-1869 Boshin war in Japan, Kōtetsu (Japanese: 甲鉄, literally "Ironclad", later renamed Azuma 東, "East") was employed as the first ironclad warship of the Imperial Japanese Navy. Built in France in 1864, and acquired from the United States in February 1869, she was an ironclad ram warship. She had a decisive role in the Naval Battle of Hakodate Bay in May 1869, which marked the end of the Boshin War, and the complete establishment of the Meiji Restoration.

War of the Pacific

In the War of the Pacific in 1879, both Peru and Chile had ironclad warships, including some of those used a few years previously against Spain. While the Independencia ran aground early on, the Peruvian ironclad Huáscar made an impact against Chilean shipping. She was eventually caught by two more modern Chilean centre-battery ironclads, the Blanco Encalada and the Almirante Cochrane at the Battle of Angamos Point.

Bombardment of Alexandria

The Royal Navy lead the way for most of the century in the number of ironclads in commission, but had few opportunities to test them in equal engagements. The largest engagement of Royal Navy ironclads took place with the bombardment of Alexandria in 1882. Defending British interests against Arabi Pasha's Egyptian revolt, a British fleet opened fire on the fortifications around the port of Alexandria. A mixture of centre-battery and turret ships bombarded Egyption positions for most of a day, forcing the Egyptians to retreat; return fire from Egyptian guns was heavy at first, but inflicted little damage, killing only five British sailors.

The Sino-Japanese War

The Japanese Empire, since its inception, had been keen to establish a modern Navy, and the Imperial Japanese Navy commissioned a number of warships from British and European shipyards, first ironclads and later armoured cruisers. This force engaged a Beiyang fleet which was superior on paper at least at the Battle of the Yalu River. Thanks to superior short-range firepower, the Japanese fleet came off better, sinking or severely damaging eight ships and receiving serious damage to only four. The naval war was concluded the next year at the Battle of Weihaiwei, where the strongest remaining Chinese ships were surrendered to the Japanese.

Use of steel

Up until the 1870s navies used mixed iron and wood construction alongside pure iron. HMS Inflexible of 1876 used teak-backed iron for its hull in the same way as the Warrior.. Iron and wood were largely interchangeable: the Japanese Kongo and Hiei ordered in 1875 were sister-ships, but one was built of iron and the other of composite construction.

By the end of the century, the advantages of steel construction were becoming apparent. Compared to iron, steel allows for greater structural strength for a lower weight. France was the first country to manufacture steel in large quantities, using the Siemens process. The French Navy's Redoutable, laid down in 1873 and launched in 1876 was a central battery and barbette warship which became the first battleship in the world to use steel as the principal building material. At that time, steel plates still had some defects, and the outer bottom plating of the ship was made of wrought iron.

Warships with all-steel constructions were later built by the Royal Navy, with the dispatch vessels Iris and Mercury, laid down in 1875 and 1876. For these, the United Kingdom initially adopted the Siemens-Martin process, but then shifted to the more economical Bessemer steel manufacturing process, so that all subsequent ships were all-steel, other than some cruisers with composite hulls (iron/steel framing and wood planking).

Steel armour also allowed experiments with case hardened armour, for instance Harvey armour.

Ironclad construction also prefigured the later debate in battleship design between tapering and 'all-or-nothing' armour design. Inflexible's armour protection was largely limited to the central citadel amidships, protecting boilers and engines , turrets and magazines, and little else.

End of the ironclad

Main Article: Battleship

The ironclad continued to be the dominant style of warship and developed into what is sometimes called the "old" battleship before being replaced by more advanced, far more seaworthy vessels known to history as pre-dreadnoughts. Among the types of ironclad were monitors (patterned after the USS Monitor), protected cruisers, armored cruisers and armored gunboats.

While the ironclad warship suffered from numerous flaws, the fact that it became the prominent naval weapon of its era and inspired nearly a century of progressively heavier armored warships can be ascribed to its massive advantage over the previous ships of the line in terms of protection. While a ship of the line could resist some damage, it was terribly vulnerable to fire and found itself completely outclassed by the new developments in naval armament beginning in the middle of the nineteenth century. Combined with steam engine propeller propulsion, the ironclad warship could outfight, outgun, and eventually outrun even the most powerful three decker.

The age of the ironclad as a main line battle craft came to an end around 1890, as iron- or steel-hulled pre-dreadnought battleships were developed and deployed.

Ironclads today

HMS Warrior is today a fully-restored museum ship in Portsmouth, England. Huáscar, after her capture from Peru was commissioned into the navy of Chile and is berthed at the port of Talcahuano, on display for visitors. . The Eads gunboat USS Cairo was sunk by a mine in the Yazoo River during the U.S. Civil War; she has since been raised and restored as much as possible, and is currently on display in Vicksburg, Mississippi. Only pieces remain of both USS Monitor and CSS Virginia. Virginia was destroyed near the end of 1862 to prevent capture off Norfolk. Monitor sank in a gale off Cape Hatteras, North Carolina in December, 1862; her wreck was discovered in 1973. Remains from both ships, including Monitor's gun turret, are on display at the Mariners' Museum in Newport News, Virginia.

Currently, Northrup-Grumman in Newport News is constructing a full-scale replica of USS Monitor. ]

Ironclads in fiction

- H.G. Wells featured the fictitious ironclad HMS Thunder Child in The War of the Worlds and also used ironclads as the inspiration for the story The Land Ironclads. Wells took the idea of ironclads and used it to create what were effectively proto-tanks, years before they came to be used in actual warfare.

- Clive Cussler featured several ironclads — namely CSS Texas — in his novel Sahara which was made into a movie of the same name.

- In Avatar: The Last Airbender, Ironclads comprise the main naval force of the Fire Nation.

References

- Greene, Jack and Massignani, Alessandro (1998). Ironclads At War. Combined Publishing. ISBN 0-938289-58-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Gardiner, Robert and Lambert, Andrew (2001). Steam, Steel and Shellfire: The Steam Warship, 1815-1905. Book Sales. ISBN 0-7858-1413-2.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Brown, DK (2003). Warrior to Dreadnought: Warship Development 1860-1905. Caxton Editions. ISBN 1-84067-529-2.

- Archibald, EHH (1984). The Fighting Ship in the Royal Navy 1897-1984. Blandford. ISBN 0-7137-1348-8.

Notes

- War at Sea in the Ironclad Age, Richard Hill, ISBN 0-304-35273-X

- War at Sea in the Ironclad Age, Richard Hill, ISBN 0-304-35273-X

- http://www.northwood.mod.uk/nwood/history/warrior/warrior.htm

- War at Sea in the Ironclad Age, Richard Hill, ISBN 0-304-35273-X

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Sondhauswas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - "Napoleon (90 guns), the first purpose-designed screw line of battleships", Steam, Steel and Shellfire, Conway's History of the Ship (p39)

- "Hastened to completion Le Napoleon was launched on 16 May 1850, to become the world's first true steam battleship", Steam, Steel and Shellfire, Conway's History of the Ship (p39)

- Steam, Steel and Shellfire, Conway's History of the Ship (p.41)

- Cite error: The named reference

Lambertwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - War at Sea in the Ironclad Age, Richard Hill, ISBN 0-304-35273-X

- http://footguards.tripod.com/06ARTICLES/ART28_blackpowder.htm]

- http://members.lycos.co.uk/Juan39/THE_WAR_WITH_SPAIN.html

- War at Sea in the Ironclad Age, Richard Hill, ISBN 0-304-35273-X

- Warships of the Imperial Japanese Navy, Jenschura Jung & Mickel, ISBN 0-85368-151-1

- Conway Marine, Steam, Steel and Shellfire (p96)

External links

- The first ironclads 1859-1872, engravings

- Ironclads and Blockade Runners of the American Civil War

- Images and text on the USS Monitor

- Circular Iron-Clads in the Imperial Russian Navy

- HMSWarrior.org