This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Zacheus (talk | contribs) at 07:05, 17 May 2007 ({{Mergefrom|Anna Halman}} <!-- Its proper text has only less than 900 chars.-->). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 07:05, 17 May 2007 by Zacheus (talk | contribs) ({{Mergefrom|Anna Halman}} <!-- Its proper text has only less than 900 chars.-->)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| It has been suggested that Anna Halman be merged into this article. (Discuss) |

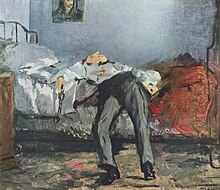

Suicide (Latin sui caedere, to kill oneself) is the act of intentionally taking one's own life. The term "suicide" can also be used to refer to a person who has killed himself or herself. Considered by modern medicine to be a mental health issue, suicide may also be caused by psychological factors such as the difficulty of coping with depression or other mental disorders. It may also stem from social and cultural pressures. Nearly a million people worldwide die by suicide annually. While completed suicides are higher in men, women have higher rates for suicide attempts. Elderly males have the highest suicide rate, although rates for young adults have been increasing in recent years.

Views toward suicide have varied in history and society. Buddhism, Christianity, Hinduism, Islam, and Judaism generally condemn suicide as a dishonorable act and some countries have made it a crime to attempt to kill oneself. In some cultures suicide may be accepted under some circumstances, such as Japanese committing seppuku for honor, suicide attacks, or the self-immolation of Buddhist monks as a form of protest.

Suicidal phenomena

Suicidal ideation

Main article: Suicidal ideationSuicidal ideation is defined as considering or fantasizing about taking one’s own life. Ideation may range from vague or unformed urges to meticulously detailed plans and posthumous instructions. According to medical practice, severe suicidal ideation, that is, serious contemplation or planning of suicide, is a medical emergency and that the condition requires immediate emergency medical treatment.

Parasuicide

Main article: ParasuicideMany suicidal people engage in suicidal activities that do not result in death. These activities fall under the clinical designation of parasuicide. Those with a history of such attempts are almost 23 times more likely to eventually end their own lives than those who don't participate in such activities.

Suicidal gestures and attempts

Sometimes, a person will make actions resembling suicide attempts while not being fully committed, or in a deliberate attempt to have others notice. This is called a suicidal gesture (also known as a "cry for help"). Prototypical methods might be a non-lethal method of self-harm that leaves obvious signs of the attempt, or simply a lethal action at a time when the person considers it likely that he/she will be rescued or prevented from fully carrying it out.

On the other hand, a person who genuinely wishes to die may fail, due to lack of knowledge about what they are doing, unwillingness to try methods that may end in permanent damage if he fails or harms others, or an unanticipated rescue, among other reasons. This is referred to as a suicide attempt.

Distinguishing between a suicidal attempt and a suicidal gesture may be difficult. Intent and motivation are not always fully discernible since so many people in a suicidal state are genuinely conflicted over whether they wish to end their lives. One approach, assuming that a sufficiently strong intent will ensure success, considers all near-suicides to be suicidal gestures. This however does not explain why so many people who fail at suicide end up with severe injuries, often permanent, which are most likely undesirable to those who are making a suicidal gesture. Another possibility is those wishing merely to make a suicidal gesture may end up accidentally killing themselves, perhaps by underestimating the lethality of the method chosen or by overestimating the possibility of external intervention by others. Suicide-like acts should generally be treated as seriously as possible because if there is an insufficiently strong reaction from loved ones from a suicidal gesture, this may motivate future, and ultimately more committed attempts.

In the technical literature the use of the terms parasuicide, or deliberate self-harm (DSH) are preferred – both of these terms avoid the question of the intent of the actions.

Suicide crisis

Main article: Suicide crisisA suicide being attempted, or a situation in which a person is seriously contemplating suicide or has strong suicidal thoughts is considered by public safety authorities to be a medical emergency requiring suicide intervention.

Suicide note

Main article: Suicide noteA written message left by someone who attempts, or indeed dies by, suicide is known as a suicide note. The practice is fairly common, occurring in approximately one out of three suicides in the United States. Motivations for leaving one range from seeking closure with loved ones to exacting revenge against others by blaming them for the decision.

Assisted suicide

A suicidal individual who lacks the physical capacity to take their own life may enlist someone else to carry out the act on their behalf, frequently a family member or physician. This may or may not be considered a form of suicide according to different moral views of the practice, with opponents regarding it instead as akin to murder. Assisted suicide is a contentious moral and political issue in many countries.

Murder-suicide

Main article: Murder-suicideSince crime just prior to suicide is often perceived as being without consequences, it is not uncommon for suicide to be linked with homicide. Motivations may range from guilt to evading punishment, insanity, killing others as part of a suicide pact or exacting revenge on those whom they feel are responsible.

Suicide attack

Main article: Suicide attackA suicide attack is when an attacker perpetrates an act of violence against others, typically to achieve a military or political goal, that foreseeably results in his or her own death as well. Suicide bombings have been prominent in the news in recent years. Other historical examples include the assassination of Tsar Alexander II and the kamikaze attacks by Japanese air pilots during the second World War.

Related phenomena

Fake suicide

Main article: PseudocidePeople sometimes fake suicide, usually in order to escape legal, financial, or relationship difficulties and start a new life. In order to explain the absence of a body, it is common to fake suicide by drowning. The term pseudocide covers not only fake suicide, but other fake deaths too (primarily fake murder). There have been numerous cases of celebrity suicides that have been challenged as possible homicides. Among the most famous were the drug overdose death of Marilyn Monroe, the alleged 1994 suicide of Kurt Cobain, and the 1993 death of Vincent Foster, a deputy White House counsel.

Self-harm

Main article: Self-harmSelf-harm is not a suicide attempt, however initially self-injury was classified as a suicide attempt. There is a non-causal correlation between self-harm and suicide; both are most commonly a joint effect of depression. A common misconception is that self-injurers are suicidal. The reality is that self-injury is a completely different from suicide in that suicide attempts to end one's life whereas self-injury is a method to cope with life and continue living.

Suicide intervention, emergency response, and treatment

Main article: Suicide interventionSuicide intervention or suicide crisis intervention is direct effort to stop or prevent persons attempting or contemplating suicide from killing themselves. Current medical advice concerning people who are attempting or seriously considering suicide is that they should immediately go or be taken to the nearest emergency room, or emergency services should be called immediately by them or anyone aware of the problem.

Modern medicine treats suicide as a mental health issue. Overwhelming or persistent suicidal thoughts are considered a medical emergency. Medical professionals advise that people who have expressed plans to kill themselves be encouraged to seek medical attention immediately. This is especially relevant if the means (weapons, drugs, or other methods) are available, or if the patient has crafted a detailed plan for executing the suicide. Medical personnel frequently receive special training to look for suicidal signs in patients. Individuals suffering from depression are considered a high-risk group for suicidal behavior. Suicide hotlines are widely available for people seeking help. However, the negative and often too clinical reception that many suicidal people receive after relating their feelings to health professionals (e.g. threats of institutionalization, increased dosages of medication, the social stigma) may cause patients to remain more guarded about their mental health history or suicidal urges and ideation.

In the United States, individuals who express the intent to harm themselves are automatically determined to lack the present mental capacity to refuse treatment, and can be transported to the emergency department against their will. An emergency physician will determine whether inpatient care at a mental health care facility is warranted. This is sometimes referred to as being "committed." A court hearing may be held to determine the patient's competence.

Suicide methods

Main article: Suicide methodsIn countries where firearms are readily available, many suicides involve the use of firearms. In fact, just over 55% of suicides that occurred in the United States in 2001 were by firearm. Asphyxiation methods (including hanging) and toxification (poisoning and overdose) are fairly common as well. Each comprised about 20% of suicides in the US during the same time period. Other methods of suicide include blunt force trauma (jumping from a building or bridge, or stepping in front of a train, for example), exsanguination or bloodletting (slitting one's wrist or throat), self-immolation, electrocution, car collision and intentional starvation.

Reasons for suicide

Causes of suicide

| This article possibly contains original research. Please improve it by verifying the claims made and adding inline citations. Statements consisting only of original research should be removed. (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Suicide poses a conundrum to sociobiologists: Why would one choose to eliminate oneself from the gene pool? Sociobiologists debate the ultimate adaptive advantage of suicidality, while at a proximate level of animal behaviour, no single factor has gained acceptance as a universal cause of suicide. Depression, however, is a common phenomenon amongst those who die by suicide. Other factors that may be related are as follows (Note that this is not meant as a comprehensive list, but rather as a summary of notable causes):

- Conscientious objection (e.g. preventing oneself from killing others if forced into an army)

- Pain (e.g. physical or emotional agony that is not correctable)

- Stress (e.g. grief after the death of a loved one)

- Crime (e.g. escaping judicial punishment and the dehumanisation and boredom of incarceration)

- Mental illness and disability (e.g. depression, bipolar disorder, trauma, obsessive compulsive disorder, body dysmorphic disorder, schizophrenia, or post traumatic stress disorder)

- Catastrophic injury (e.g. paralysis, disfigurement, loss of limb)

- Substance abuse

- Adverse environment (e.g. sexual abuse, domestic abuse, poverty, homelessness, discrimination, bullying, fear of murder and/or torture)

- Financial loss (e.g. gambling addiction, loss of job/assets, stock market crash, debts)

- Sacrificial reasons (e.g. a soldier throwing his body on a grenade, a man throwing his body in front of a vehicle.)

- Unresolved sexual issues (e.g. sexual orientation, gender dysphoria, unrequited love, aftermath of a break up)

- To avoid shame or dishonour (e.g. Under the Bushido ideal, if a samurai failed to uphold his honour, he could regain it by performing seppuku.)

- Terrorism can also be a motive for suicide, especially when related to religion (e.g., suicide bombings)

- Extreme nationalism (e.g., the Kamikaze, Selbstopfer, and Kaiten suicide weapons)

- Loneliness when a person feels totally disconnected from his or her surroundings or remaining single for so long.

- Philosophical reasons. Many who subscribe to absurdism believe that life is ultimately meaningless and absurd, and thus there is no reason to continue living.

- Religion and cults. Often, cults only become popularly known after mass suicides, where those who kill themselves believe it will lead to salvation or eternal happiness, such as Heaven's Gate and Peoples Temple.

- Curiosity (the need to know what happens after death.)

- A physically demanding or stressfull illness (Cancer, Epilepsy)

Suicide and mental illness

| This section needs expansion. You can help by making an edit requestadding to it . |

Suicide is sometimes associated with mental illnesses such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, where the cases of suicide or attempted suicide can be more common than in people without a history of mental illness. Suicide among schizophrenics can be caused by either the depression that is common with the illness, or is due to the brain commanding the person to kill themself which can cause the person to do it on impulse. Suicide among people suffering from bipolar disorder is often an impulse, which is due to the sufferer's extreme mood swings (one of the main symptoms of bipolar disorder).

Epidemiology

Main article: Epidemiology and methodology of suicide

According to official statistics, about a million people die by suicide annually, more than those murdered or killed in war. As of 2001 in the USA, suicides outnumber homicides by 3 to 2 and deaths from AIDS by 2 to 1

Gender and suicide: In the Western world, males die much more often than females by suicide, while females attempt suicide more often. Some medical professionals believe this is due to the fact that males are more likely to end their life through violent means (guns, knives, hanging, drowning, etc.), while women primarily overdose on medications or use other methods which may be ineffective. Others ascribe the difference to inherent differences in male/female psychology. Greater social stigma against male depression and a lack of social networks of support and help with depression is often identified as a key reason for men's disproportionately higher level of suicides, since "suicide as a cry for help" is not seen as an equally viable option by men. Typically males die from suicide 3 to 4 times as often as females, and not unusually 5 or more times as often.

Excess male mortality from suicide is also evident from data from non-western countries. In 1979-81, 74 territories reported one or more cases of suicides. Two of these reported equal rates for the sexes: Seychelles and Kenya. Three territories reported female rates exceeding male rates: Papua-New Guinea, Macau, French Guiana. The remaining 69 territories had male suicide rates greater than female suicide rates.

| Rank | Country | Year | Males | Females | Total |

| 1. | Lithuania | 2003 | 74.3 | 13.9 | 42.1 |

| 2. | Russia | 2002 | 69.3 | 11.9 | 38.7 |

| 3. | Belarus | 2003 | 63.3 | 10.3 | 35.1 |

| 4. | Kazakhstan | 2002 | 50.2 | 8.8 | 28.8 |

| 5. | Slovenia | 2003 | 45.0 | 12.0 | 28.1 |

| 6. | Hungary | 2003 | 44.9 | 12.0 | 27.7 |

| 7. | Estonia | 2002 | 47.7 | 9.8 | 27.3 |

| 8. | Ukraine | 2002 | 46.7 | 8.4 | 26.1 |

| 9. | Latvia | 2003 | 45.0 | 9.7 | 26.0 |

| 10. | Japan | 2002 | 35.2 | 12.8 | 23.8 |

Barraclough found that the female rates of those aged 5-14 equaled or exceeded the male rates only in 14 countries, mainly in South America and Asia.

National suicide rates sometimes tend to be stable. For example, the 1975 rates for Australia, Denmark, England, France, Norway, and Switzerland, were within 3.0 per 100,000 of population from the 1875 rates. The rates in 1910-14 and in 1960 differed less than 2.5 per 100,000 of population in Australia, Belgium, Denmark, England & Wales, Ireland, Japan, New Zealand, Norway, Scotland, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, and The Netherlands.

There are considerable differences between national suicide rates. Findings from two studies showed a range from 0.0 to more than 40 suicides per 100,000 of population.

National suicide rates, apparently universally, show an upward long-term trend. This trend has been well documented for European countries. The trend for national suicide rates to rise slowly over time might be an indirect result of the gradual reduction in deaths from other causes, i.e. falling death rates from causes other than suicide uncover a previously hidden predisposition towards suicide. There may also be an explanation in the reduced stigma attached to survivors as suicide is no longer a crime or a sin. This may allow coroners to record more suicides as such and so increase stats.

Race and suicide. At least in the USA, Caucasians die by suicide more often than African Americans do. This is true for both genders. Non-Hispanic Caucasians are nearly 2.5 times more likely to kill themselves than are African Americans or Hispanics.

Age and suicide At least in the USA, males over 70 die by suicide more often than younger males. There is no such trend for females. Older non-Hispanic Caucasian men are much more likely to kill themselves than older men or women of any other group, which contributes to the relatively high suicide rate among Caucasians. Caucasian men in their 20s, conversely, kill themselves only slightly more often than African American or Hispanic men in the same age group.

Season and suicide People die by suicide more often during spring and summer. The idea that suicide is more common during the winter holidays (including Christmas in the northern hemisphere) is a common misconception.

Other reasons

Suicide as a form of defiance and protest

Heroic suicide, for the greater good of others, is often celebrated. For instance, Mahatma Gandhi went on a hunger strike to prevent fighting between Hindus and Muslims, and, although he was stopped before dying, it appeared he would have willingly succumbed to starvation. This attracted attention to Gandhi's cause, and generated a great deal of respect for him as a spiritual leader. In the 1960s, Buddhist monks, most notably Thích Quảng Đức, in South Vietnam drew Western attention to their protests against President Ngô Đình Diệm by burning themselves to death. Similar events were reported during the Cold War in eastern Europe, such as the death of Jan Palach following the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia, or Romas Kalanta's self-immolation in the main street of Kaunas, Lithuania in 1972. More recently, an American anti-war activist, Malachi Ritscher died by suicide by self-immolation as a protest against the Iraq war. In Ireland there exists a long tradition of hunger strike to the death against British rule, viz the pre independence death of Terence McSwiney in Cork and more recently for those interned without trial and refused political status in Northern Ireland. Critics may see such suicides as counter-productive, arguing that these people would probably achieve a comparable or greater result by spending the rest of their lives in active struggle.

Military suicide

Main article: Suicide attack

In the desperate final days of World War II, many Japanese pilots volunteered for kamikaze missions in an attempt to forestall defeat for the Empire. In Nazi Germany, Luftwaffe squadrons were formed to smash into American B-17s during daylight bombing missions, in order to delay the highly-probable Allied victory, although in this case, inspiration was primarily the Soviet and Polish taran ramming attacks, and death of the pilot was not a desired outcome. The degree to which such a pilot was engaging in a heroic, selfless action or whether they faced immense social pressure is a matter of historical debate. The Japanese also built one-man "human torpedo" suicide submarines.

However, suicide has been fairly common in warfare throughout history. Soldiers and civilians committed suicide to avoid capture and slavery (including the wave of German and Japanese suicides in the last days of World War II). Commanders committed suicide rather than accept defeat. Spies and officers have often committed suicide to avoid revealing secrets under interrogation and/or torture. Behaviour that could be seen as suicidal occurred often in battle. For instance, soldiers under cannon fire at the Battle of Waterloo took fatal hits rather than duck and place their comrades in harm's way. The Charge of the Light Brigade in the Crimean War, Pickett's Charge at Gettysburg in the American Civil War , and the charge of the French cavalry at the Battle of Sedan in the Franco-Prussian War were assaults that continued even after it was obvious to participants that the attacks were unlikely to succeed and would probably be fatal to most of the attackers. Japanese infantrymen usually fought to the last man, launched "banzai" suicide charges, and suicided during the Pacific island battles in World War II. In Saipan and Okinawa, civilians joined in the suicides. Suicidal attacks by pilots were common in the 20th century: the attack by U.S. torpedo planes at the Battle of Midway was very similar to a kamikaze attack.

Impact of suicide

It is estimated that an average of six people are suicide "survivors" for each suicide that occurs in the United States. In the context of suicide, the word "survivors" refers to the family and friends of the person who has died by suicide; this figure therefore does not represent the total number of people who may be affected. For example, the suicide of a child may leave the school and their entire community left to make sense of the act.

As with any death, family and friends of a suicide victim feel grief associated with loss. These suicide survivors are often overwhelmed with psychological trauma as well, depending on many factors associated with the event. This trauma can leave survivors feeling guilty, angry, remorseful, helpless, and confused. It can be especially difficult for survivors because many of their questions as to why the victim felt the need to take his or her own life are left unanswered. Moreover, survivors often feel that they have failed or that they should have intervened in some way. Given these complex sets of emotions associated with a loved one's suicide, survivors usually find it difficult to discuss the death with others, causing them to feel isolated from their own network of family and friends and often making them reluctant to form new relationships as well.

"Survivor groups" can offer counseling and help bring many of the issues associated with suicide out into the open. They can also help survivors reach out to their own friends and family who may be feeling similarly and thus begin the healing process. In addition, counseling services and therapy can provide invaluable support to the bereaved. Some such groups can be found online, providing a forum for discussion amongst survivors of suicide (see Support Groups for Survivors section below).

Economic impact

Deaths and injuries from suicidal behavior represent $25 billion each year in direct costs, including health care services, funeral services, autopsies and investigations, and indirect costs like lost productivity.

These costs may be counterbalanced by economic gains. Expenditure on those who would have continued living is reduced, including pensions, social security, health care services for the mentally ill as well as other normal budgetary expenditure per head of living population.

Views on suicide

Criminal

Main article: Legal views of suicideIn some jurisdictions, an act or failed act of suicide is considered to be a crime. Some places consider failure to be attempted murder, with the victim being oneself, and will prosecute such offenders for attempted murder. More commonly, a surviving party member who assisted in the suicide attempt will face criminal charges.

In Brazil, suicide is not a crime, but willfully instigating or assisting in its completion is. If the help is directed to a minor, the penalty is applied in its double and not considered as homicide. In Italy and Canada, instigating another to suicide is also a criminal offence. In Singapore, assisting in the suicide of a mentally-handicapped person is a capital offense.

Cultural

Main article: Cultural views of suicideIn the Warring States Period and the Edo period of Japan, samurai who disgraced their honor chose to end their own lives by seppuku, a method in which the samurai takes a sword and slices into his abdomen, causing a fatal injury. The cut is usually performed diagonally from the top corner of the samurai's writing hand, and has long been considered an honorable form of death (even when done to punish dishonor). Though such a wound would be fatal, seppuku was not always technically suicide, as the samurai's assistant (the kaishaku) would stand by to cut short any suffering by quickly administering decapitation, sometimes as soon as the first tiny incision into the abdomen was made.

Religious

Main article: Religious views of suicideSuicide is considered a sin by most Christian groups, including the Catholic Church, based largely on the writings of influential Christian thinkers of the middle ages, such as St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas. Their arguments are based largely around the commandment, "thou shalt not kill" (made applicable under the New Covenant by Christ in Matthew 19:18), and the ideas that life is a gift given by God which should not be spurned, and that suicide is against the "natural order" and thus interferes with God's master plan for the world. However, suicide was not considered a sin under the Byzantine Christian code of Justinian, for instance . Counter-arguments include the following: that the sixth commandment is more accurately translated as "thou shalt not murder," not necessarily applying to the self; that taking one's own life no more violates God's plan than does curing a disease; and that a number of suicides by followers of God are recorded in the Bible with no dire condemnation.

Suicide is not allowed in the religion of Islam. Suicide by Muslim standards is a sign of disbelief in God.

Debate over suicide

Main article: Philosophical views of suicideSome see suicide as a legitimate matter of personal choice and a human right (colloquially known as the right to die movement), and maintain that no one should be forced to suffer against their will, particularly from conditions such as incurable disease, mental illness, and old age that have no possibility of improvement. Proponents of this view reject the belief that suicide is always irrational, arguing instead that it can be a valid, albeit drastic, last resort for those enduring major pain or trauma. This perspective is most popular in Continental Europe, where euthanasia and other such topics are commonly discussed in parliament, although it has a good deal of support in the United States as well.

A narrower segment of this group considers suicide something between a grave but condonable choice in some circumstances and a sacrosanct right for anyone (even a young and healthy person) who believes they have rationally and conscientiously come to the decision to end their own lives. Notable supporters of this school of thought include German pessimist philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer, and Scottish empiricist David Hume. Adherents of this view often advocate the abrogation of statutes that restrict the liberties of people known to be suicidal, such as laws permitting their involuntary commitment to mental hospitals. Critics may argue that suicidal impulses are often products of mental illness rather than rational self-interest, and that because of the gravity and irreversibility of the decision to take one's life it is more prudent for society to err on the side of caution and at least delay the suicidal act.

See also

- alt.suicide.holiday

- American Foundation for Suicide Prevention

- The choking game

- Cult suicide

- Dutiful suicide

- Mass suicide

- Meaning of life

- Quantum suicide

- Russian roulette

- Self-harm

- Senicide in antiquity

- Suicide Act 1961

- Suicide attack

- Suicide (book)

- Suicide booth

- Suicide bridge

- Suicide note

- Terminal illness

- Misplaced Pages:Responding to suicidal individuals

Lists

- List of countries by suicide rate

- List of films about suicide

- List of songs about suicide

- List of suicide sites

- List of suicides

Further reading

Documents and periodicals

- Frederick, C. J. Trends in Mental Health: Self-destructive Behavior Among Younger Age Groups. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse. 1976. ED 132 782.

- Lipsitz, J. S., Making It the Hard Way: Adolescents in the 1980s. Testimony presented to the Crisis Intervention Task Force of the House Select Committee on Children, Youth, and Families. 1983. ED 248 002.

- McBrien, R. J. "Are You Thinking of Killing Yourself? Confronting Suicidal Thoughts." SCHOOL COUNSELOR 31 (1983): 75–82.

- Ray, L. Y. "Adolescent Suicide." Personnel and Guidance Journal 62 (1983): 131-35.

- Rosenkrantz, A. L. "A Note on Adolescent Suicide: Incidence, Dynamics and Some Suggestions for Treatment." Adolescence 13 (l978): 209–14.

- Suicide Among School Age Youth. Albany, NY: The State Education Department of the University of the State of New York, 1984. ED 253 819.

- Suicide and Attempted Suicide in Young People. Report on a Conference. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 1974. ED 162 204.

- Teenagers in Crisis: Issues and Programs. Hearing Before the Select Committee on Children, Youth, and Families. House of Representatives Ninety-eighth Congress, First Session. Washington, DC: Congress of the U. S., October, 1983. ED 248 445.

- Smith, R. M. Adolescent Suicide and Intervention in Perspective. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the National Council on Family Relations, Boston, MA, August, 1979. ED 184 017.

Nonfiction books

- Bongar, B. The Suicidal Patient: Clinical and Legal Standards of Care. Washington, D.C.: APA. 2002. ISBN 1-55798-761-0

- Durkheim, Emile. Suicide, (1897), The Free Press reprint 1997, ISBN 0684836327

- Jamison, Kay Redfield (2000). Night Falls Fast: Understanding Suicide. Vintage. ISBN 0-375-70147-8.

- Humphry, Derek. Final Exit: The Practicalities of Self-Deliverance and Assisted Suicide for the Dying. Dell. 1997.

- Maguire, Maureen, Uncomfortably Numb. A Prison Requiem. Luath Press 2001. ISBN 1-84282-001-X (A factual documentation of suicide in prison)

- O'Connor, R., & Sheehy, N.P. Understanding Suicidal Behaviour. BPS Blackwell. 2000. ISBN 1854332902

- Paul, Sam. Why I Committed Suicide. New York: iUniverse, Inc., 2004. ISBN 0-59532-695-1

- Stone, Geo. Suicide and Attempted Suicide: Methods and Consequences. New York: Carroll & Graf, 2001. ISBN 0-7867-0940-5

- Danielle Patterson " Why people go crazy"

External links

General information

- Medline Plus - suicide and suicidal behavior

- cbel.com/suicide/ - directory of information on suicide

- American Association of Suicidology - statistics and general information

- Online Education on Suicide Prevention for Professionals - list of courses for medical professionals

Suicide prevention

- ChooseLife,Choose Life is a 10 year plan aimed at reducing suicides in Scotland by 20% by 2013, Looking at ways of preventing Suicide using ASIST,SafeTALK and SuicideTALK

- Kristin Brooks Hope Center

- Youth America Hotline

- Preventing Suicide The National Journal

- resources for graduate students who are depressed and or suicidal

- American Foundation for Suicide Prevention

- metanoia.org/suicide - suicide prevention page

- "Understanding and Helping the Suicidal Person" - information on suicide prevention

- The Fred Fund : suicide support, resources, online stories, memorials and interaction

- TeenSuicide.us - teenage suicide prevention information

- Suicide Prevention Help - A Friendship Letter and Web directory of helpful suicide prevention resources from around the world.

Views on suicide

- The Eclipse: A Memoir of Suicide - a detailed examination of suicide's underlying philosophical beliefs and its impact on survivors

- "The Murder of Oneself" - ethical and legal considerations in suicide and its prevention

- The Debate: a pro-choice FAQ

- "Suicide as a Moral Alternative" - discussion on the morality of suicide, including arguments for and against

- "Suicide" in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Suicide & Euthanasia - a Biblical Perspective - discussion of suicide from a biblical perspective

- * Suicide Promotion (Internet) - United Kingdom Parliamentary debate - debate by politicians on suicide, 25 January 2005

Support groups

- Template:Dmoz

- Samaritans (UK & Ireland) - 24-hour support help, United Kingdom & Ireland

- Befrienders Worldwide Worldwide Suicide Prevention help

- #alt.suicide.bus.stop (ASBS) - a support group for the suicidal, by the suicidal

- Maytree Respite Centre - A refuge for people in a suicidal crisis. They welcome referrals or self-referrals

Support groups for survivors

- American Association of Suicidology - Referrals to local self help groups for survivors of suicide across the United States

- Heartbeat - Mutual support for those who have lost loved ones to suicide

- SOLES - Survivors of Law Enforcement Suicide

- International Friends and Families of Suicide - Online support for survivors internationally

- Parents of Suicide - Support via chatrooms and email for those who have lost sons or daughters to suicide

- "How can suicide be prevented?". 2005-09-09. Retrieved 2007-04-13.

- Shaffer, D.J. (1988). "The Epidemiology of Teen Suicide: An Examination of Risk Factors". Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 49 (supp.): 36–41. PMID 3047106.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Zogby Poll.

- "U.S. Suicide Statistics (2001)". Retrieved 2007-04-13.

- "Suicide and suicide prevention among gays and lesbians". Retrieved 2007-04-13.

- "Suicide prevention". WHO Sites: Mental Health. World Health Organization. February 16, 2006. Retrieved 2006-04-11.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - "Teen Suicide Statistics". Adolescent Teenage Suicide Prevention. FamilyFirstAid.org. 2001. Retrieved 2006-04-11.

- Lester, Patterns, Table 3.3, pp. 31-33

- Table of WHO suicide rates by gender as of December 2005.

- WHO country reports and charts for suicide rates retrieved June 6, 2006.

- Barraclough,B M. Sex ratio of juvenile suicide. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 1987, 26, 434-435.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics, 1983; Lester, Patterns, 1996, p. 21

- Lester, Patterns, 1996, p. 22

- La Vecchia, C., Lucchini, F., & Levi, F. (1994) Worldwide trends in suicide mortality, 1955-1989. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 90, 53-64.; Lester, Patterns, 1996, pp. 28-30.

- Lester, Patterns, 1996, p. 2.

- Baldessarini, R. J., & Jamison, K. R. (1999) Effects of medical interventions on suicidal behavior. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 60 (Suppl. 2), 117-122.

- Khan, A., Warner, H. A., & Brown, W. A. (2000) Symptom reduction and suicide risk in patients treated with placebo in antidepressant clinical trials. Archives of General Psychiatry, 57, 311-317.

- Template:PDFlink

- "Questions About Suicide". Centre For Suicide Prevention. 2006.

- http://www.suicidology.org/displaycommon.cfm?an=6

- http://www.faqs.org/faqs/suicide/info/

- "Preventing suicide" (PDF). Retrieved 2007-04-13.

- "The Cost of Suicide Mortality in New Brunswick, 1996". 1996. Retrieved 2007-04-13.

- Yang B, Lester D. Recalculating the economic cost of suicide. Death studies, 2007 Apr;31(4):351-61