This is an old revision of this page, as edited by 70.79.96.123 (talk) at 17:36, 31 March 2008 (→Biography). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 17:36, 31 March 2008 by 70.79.96.123 (talk) (→Biography)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| Eric Arthur Blair | |

|---|---|

| |

| Pen name | George Orwell |

| Occupation | Writer; author, journalist |

| Notable works | Animal Farm (1945) Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949) |

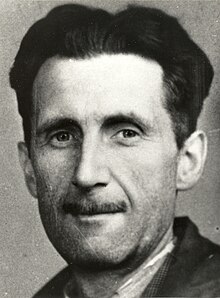

George Orwell is the pen name of Eric Arthur Blair (25 June, 1903 – 21 January 1950) who was an English writer and journalist well-noted as a novelist, critic, and commentator on politics and culture.

George Orwell is one of the most admired English-language essayists of the twentieth century, and most famous for two novels critical of totalitarianism in general (Nineteen Eighty-Four), and Stalinism in particular (Animal Farm), which he wrote and published towards the end of his life.

your mom

Legacy

Literary criticism

Throughout his life Orwell continually supported himself as a book reviewer, writing works so long and sophisticated they have had an influence on literary criticism. In the celebrated conclusion to his 1940 essay on Charles Dickens one seems to see Orwell himself:

- "When one reads any strongly individual piece of writing, one has the impression of seeing a face somewhere behind the page. It is not necessarily the actual face of the writer. I feel this very strongly with Swift, with Defoe, with Fielding, Stendhal, Thackeray, Flaubert, though in several cases I do not know what these people looked like and do not want to know. What one sees is the face that the writer ought to have. Well, in the case of Dickens I see a face that is not quite the face of Dickens's photographs, though it resembles it. It is the face of a man of about forty, with a small beard and a high colour. He is laughing, with a touch of anger in his laughter, but no triumph, no malignity. It is the face of a man who is always fighting against something, but who fights in the open and is not frightened, the face of a man who is generously angry — in other words, of a nineteenth-century liberal, a free intelligence, a type hated with equal hatred by all the smelly little orthodoxies which are now contending for our souls."

Rules for writers

In "Politics and the English Language," George Orwell provides six rules for writers:

- Never use a metaphor, simile, or other figure of speech which you are used to seeing in print.

- Never use a long word where a short one will do.

- If it is possible to cut a word out, always cut it out.

- Never use the passive voice where you can use the active.

- Never use a foreign phrase, a scientific word, or a jargon word if you can think of an everyday English equivalent.

- Break any of these rules sooner than say anything outright barbarous.

Political views

Orwell's political views shifted over time, but he was a man of the political left throughout his life as a writer. In his earlier days he occasionally described himself as a "Tory anarchist". His time in Burma made him a staunch opponent of imperialism, and his experience of poverty while researching Down and Out in Paris and London and The Road to Wigan Pier turned him into a socialist. "Every line of serious work that I have written since 1936 has been written, directly or indirectly, against totalitarianism and for democratic socialism, as I understand it," he wrote in 1946.

It was the Spanish Civil War that played the most important part in defining his socialism. Having witnessed the success of the anarcho-syndicalist communities, and the subsequent brutal suppression of the anarcho-syndicalists and other revolutionaries by the Soviet-backed Communists, Orwell returned from Catalonia a staunch anti-Stalinist and joined the Independent Labour Party.

At the time, like most other left-wingers in the United Kingdom, he was still opposed to rearmament against Nazi Germany — but after the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact and the outbreak of the Second World War, he changed his mind. He left the ILP over its pacifism and adopted a political position of "revolutionary patriotism". He supported the war effort but detected (wrongly as it turned out) a mood that would lead to a revolutionary socialist movement among the British people. "We are in a strange period of history in which a revolutionary has to be a patriot and a patriot has to be a revolutionary," he wrote in Tribune, the Labour left's weekly, in December 1940.

By 1943, his thinking had moved on. He joined the staff of Tribune as literary editor, and from then until his death was a left-wing (though hardly orthodox) Labour-supporting democratic socialist. He canvassed for the Labour Party in the 1945 general election and was broadly supportive of its actions in office, though he was sharply critical of its timidity on certain key questions and despised the pro-Soviet stance of many Labour left-wingers.

Although he was never either a Trotskyist or an anarchist, he was strongly influenced by the Trotskyist and anarchist critiques of the Soviet regime and by the anarchists' emphasis on individual freedom. He wrote in The Road to Wigan Pier that 'I worked out an anarchistic theory that all government is evil, that the punishment always does more harm than the crime and the people can be trusted to behave decently if you will only let them alone.' In typical Orwellian style, he continues to deconstruct his own opinion as 'sentimental nonsense'. He continues 'it is always necessary to protect peaceful people from violence. In any state of society where crime can be profitable you have got to have a harsh criminal law and administer it ruthlessly'. Many of his closest friends in the mid-1940s were part of the small anarchist scene in London.

Orwell had little sympathy with Zionism and opposed the creation of the state of Israel. In 1945, Orwell wrote that "few English people realise that the Palestine issue is partly a colour issue and that an Indian nationalist, for example, would probably side with the Arabs".

While Orwell was concerned that the Palestinian Arabs be treated fairly, he was equally concerned with fairness to Jews in general: writing in the spring of 1945 a long essay titled "Antisemitism in Britain," for the "Contemporary Jewish Record." Antisemitism, Orwell warned, was "on the increase," and was "quite irrational and will not yield to arguments." He thought "the only useful approach" would be a psychological one, to discover "why" antisemites could "swallow such absurdities on one particular subject while remaining sane on others." (pp 332-341, As I Please: 1943-1945.) In his magnum opus, Nineteen Eighty-Four, he showed the Party enlisting antisemitic passions in the Two Minute Hates for Goldstein, their archetypal traitor.

Orwell was also a proponent of a federal socialist Europe, a position outlined in his 1947 essay 'Toward European Unity', which first appeared in Partisan Review.

Work

During the majority of his career, Orwell was best known for his journalism, in essays, reviews, columns in newspapers and magazines and in his books of reportage: Down and Out in Paris and London (describing a period of poverty in these cities), The Road to Wigan Pier (describing the living conditions of the poor in northern England, and the class divide generally) and Homage to Catalonia. According to Newsweek, Orwell "was the finest journalist of his day and the foremost architect of the English essay since Hazlitt."

Modern readers are more often introduced to Orwell as a novelist, particularly through his enormously successful titles Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four. The former is often thought to reflect developments in the Soviet Union after the Russian Revolution; the latter, life under totalitarian rule. Elements in Nineteen Eighty-Four satirize "opium for the masses" found as central-character Winston Smith does (witness the newspapers filled with "sex, sport, and astrology" which the Ministry of Truth peddles to the proles). Nineteen Eighty-Four is often compared to Brave New World by Aldous Huxley; both are powerful dystopian novels warning of a future world filled with state control, the former was written later and considers perpetual war preparation in a nuclear age; the latter is more optimistic.

Influence on the English language

Some of Nineteen Eighty-Four's lexicon has entered into the English language.

- Orwell expounded on the importance of honest and clear language (and, conversely, on how misleading and vague language can be a tool of political manipulation) in his 1946 essay Politics and the English Language. The language of Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four is Newspeak: a thoroughly politicised and obfuscatory language designed to make coherent thought impossible by limiting acceptable word choices.

- Another phrase is 'Big Brother', or 'Big Brother is watching you'. Today, security cameras are often thought to be modern society's big brother. The current television reality show Big Brother carries that title because of Nineteen Eighty-Four.

- The same novel spawned the title of another television series, Room 101.

- The phrase 'thought police' is also derived from Nineteen Eighty-Four, and might be used to refer to any alleged violation of the right to the free expression of opinion. It is particularly used in contexts where free expression is proclaimed and expected to exist.

- Doublethink is a Newspeak term from Nineteen Eighty-Four, and is the act of holding two contradictory beliefs simultaneously, fervently believing both.

Variations of the slogan "all animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others", from Animal Farm, are sometimes used to satirise situations where equality exists in theory and rhetoric but not in practice with various idioms. For example, an allegation that rich people are treated more leniently by the courts despite legal equality before the law might be summarised as "all criminals are equal, but some are more equal than others". This appears to echo the phrase Primus inter pares - the Latin for "First amongst equals", which is usually applied to the head of a democratic state.

Although the origins of the term are debatable, Orwell may have been the first to use the term cold war. He used it in an essay titled "You and the Atomic Bomb" on October 19, 1945 in Tribune, he wrote:

- "We may be heading not for general breakdown but for an epoch as horribly stable as the slave empires of antiquity. James Burnham's theory has been much discussed, but few people have yet considered its ideological implications — this is, the kind of world-view, the kind of beliefs, and the social structure that would probably prevail in a State which was at once unconquerable and in a permanent state of 'cold war' with its neighbours."

Literary influences

In an autobiographical sketch Orwell sent to the editors of Twentieth Century Authors in 1940, he wrote:

Elsewhere, Orwell strongly praised the works of Jack London, especially his book The Road. Orwell's investigation of poverty in The Road to Wigan Pier strongly resembles that of Jack London's The People of the Abyss, in which the American journalist disguises himself as an out-of-work sailor in order to investigate the lives of the poor in London. In the essay "Politics vs. Literature: An Examination of Gulliver's Travels" (1946) he wrote: "If I had to make a list of six books which were to be preserved when all others were destroyed, I would certainly put Gulliver's Travels among them." Other writers admired by Orwell included Ralph Waldo Emerson, G. K. Chesterton, George Gissing, Graham Greene, Herman Melville, Henry Miller, Tobias Smollett, Mark Twain, Joseph Conrad and Yevgeny Zamyatin. He was both an admirer and a critic of Rudyard Kipling, praising Kipling as a gifted writer and a "good bad poet" whose work is "spurious" and "morally insensitive and aesthetically disgusting," but undeniably seductive and able to speak to certain aspects of reality more effectively than more enlightened authors. Orwell also publicly defended P. G. Wodehouse against charges of being a Nazi sympathiser; a defence based on Wodehouse's disinterest in and ignorance of politics.

Intelligence

Expectedly, the Special Branch in the UK, the police intelligence group, spied on Orwell during the greater part of his life.. The dossier published by Britain's National Archives mentions that according to one investigator, Orwell's tendency of clothing himself "in Bohemian fashion," revealed that the author was "a Communist":

"This man has advanced Communist views, and several of his Indian friends say that they have often seen him at Communist meetings. He dresses in a bohemian fashion both at his office and in his leisure hours."

Conversely, there has been speculation about the extent of Orwell's links to Britain's secret service, MI5, and some have even claimed that he was in the service's employ. The evidence for this claim is contested.

Orwell also had an NKVD file due to his involvement with the POUM militia during the Spanish Civil War.

Personal life

George Orwell and Cyril Connolly were contemporaries at St Cyprian's and at Eton, though they hardly spoke at Eton as they were in separate years. They later became friends; Connolly helping a prep school companion by introducing him to London literary circles. The St Cyprian's Headmaster saw that Eric "was made to study like a dog" to earn a scholarship; Eric alleged that was solely to enhance the school's prestige with parents, so accounting for his lackadaisical approach to studies at Eton.

The Blair family lived at Shiplake before World War I, and Eric was friendly with the Buddicom family, especially Jacintha Buddicom with whom he read and wrote poetry, and dreamt of intellectual adventures. Simultaneously, he enjoyed shooting, fishing, and birdwatching with Jacintha’s brother and sister. He told her that he might write a book in similar style to that of H. G. Wells's A Modern Utopia. Jacintha Buddicom repudiated Orwell's schoolboy misery described in Such, Such Were the Joys, claiming he was a specially happy child, yet acknowledging he was a boy, aloof and undemonstrative, who did not need a wide circle of friends. He and she lost touch shortly after Orwell went to Burma, becoming unsympathetic to him because of letters he wrote complaining about his life; she ceased replying.

Whilst living in poor lodgings on Portobello Road on returning from Burma, his family friend recalls:

That winter was very cold. Orwell had very little money, indeed. I think he must have suffered in that unheated room, after the climate of Burma . . . Oh yes, he was already writing. Trying to write that is – it didn't come easily . . . To us, at that time, he was a wrong-headed young man who had thrown away a good career, and was vain enough to think he could be an author. But the formidable look was not there for nothing. He had the gift, he had the courage, he had the persistence to go on in spite of failure, sickness, poverty, and opposition, until he became an acknowledged master of English prose.

In The Road to Wigan Pier he writes of tramping and poverty:

When I thought of poverty, I thought of it in terms of brute starvation. Therefore my mind turned immediately towards the extreme cases, the social outcasts: tramps, beggars, criminals, prostitutes. These were the 'lowest of the low', and these were the people with whom I wanted to get into contact. What I profoundly wanted at that time was to find some way of getting out of the respectable world altogether.

The business relationship between Orwell and Victor Gollancz, his first publisher, was stiff: for example, in letters, Orwell always addressed him by surname, as "Gollancz". Two items in their relation are of particular interest. The first, Orwell apparently never voiced objection to Gollancz's apologetic preface to A Road to Wigan Pier; the second, he released Orwell from his contract (at Orwell's request) so that Secker & Warburg could publish his fiction. Gollancz's refusal to publish Animal Farm considerably delayed the book's publication. As a Soviet sympathizer, Gollancz was more interested in his non-fiction writing, finding Animal Farm politically too hot.

Eileen O'Shaughnessy was warned off Orwell by friends who warned that she did not know what she was taking on. After her death during a hysterectomy, in a letter to a friend, Orwell refers to her as 'a faithful old stick'; the depth of his love for her remains ambiguous. Eileen's symptoms may partly account for Orwell's infidelities in the war's last years, but, in a letter to a woman to whom he proposed marriage: 'I was sometimes unfaithful to Eileen, and I also treated her badly, and I think she treated me badly, too, at times, but it was a real marriage, in the sense that we had been through awful struggles together and she understood all about my work, etc.' Bernard Crick compares them to Thomas Hardy and Emma Gifford: 'Certainly with a great writer the writing comes first. One thinks of Thomas Hardy, subtle in his characters, but obtuse to the actual suffering of his first wife.' Nevertheless, Orwell was very lonely after Eileen's death, and desperate for a wife, both as companion for himself and as mother for Richard; he proposed marriage to four women, eventually, Sonia Brownwell accepted.

Bob Edwards, who fought with him in Spain, said: 'He had a phobia against rats. We got used to them. They used to gnaw at our boots during the night, but George just couldn't get used to the presence of rats and one day, late in the evening, he caused us great embarrassment . . . he got out his gun and shot it . . . the whole front, and both sides, went into action.'

On Sundays, Orwell liked very rare roast beef, and Yorkshire pudding dripping with gravy, and good Yarmouth kippers at high tea. (p.501) . . . He liked his tea, as well as his tobacco, strong, sometimes putting twelve spoonfuls into a huge brown teapot requiring both hands to lift.

His wardrobe was famously casual: 'an awful pair of thick corduroy trousers', a pair of thick, grey flannel trousers, a 'rather nice' black corduroy jacket, a shaggy, battered, green-grey Harris tweed jacket, and a 'best suit' of dark-grey-to-black herringbone tweed of old-fashioned cut.

Younger sister, Avril, joined him at Barnhill, Jura, as housekeeper. Like her brother, she was of tough character, and eventually drove away Richard Orwell's nanny, because the house was too small for both women. Orwell also nearly died during an unfortunate boating expedition in that time.

Of Orwell, Bernard Crick writes:

... he was both a brave man and one who drove himself hard, for the sake, first, of 'writing' and then more and more for an integrated sense of what he had to write. Orwell was unusually reticent to his friends about his background and his life, his openness was all in print for literary or moral effect; he tried to keep his small circle of good friends well apart – people are still surprised to learn who else at the time he knew; he did not confide in people easily, not talk about his emotions – even to women with whom he was close; he was not fully integrate as a person, not quite comfortable within his own skin, until late in his life – and he was many-faceted, not a simple man at all.

Shelden noted Orwell’s obsessive belief in his failure, and the deep inadequacy haunting him through his career:

Playing the loser was a form of revenge against the winners, a way of repudiating the corrupt nature of conventional success – the scheming, the greed, the sacrifice of principles. Yet, it was also a form of self-rebuke, a way of keeping one’s own pride and ambition in check.

According to T.R. Fyvel:

His crucial experience . . . was his struggle to turn himself into a writer, one which led through long periods of poverty, failure and humiliation, and about which he has written almost nothing directly. The sweat and agony was less in the slum-life than in the effort to turn the experience into literature.

Bibliography

Novels

- Burmese Days (1934) —

- A Clergyman's Daughter (1935) —

- Keep the Aspidistra Flying (1936) —

- Coming Up for Air (1939) —

- Animal Farm (1945) —

- Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949) —

Books based on personal experiences

- Down and Out in Paris and London (1933) —

- The Road to Wigan Pier (1937) —

- Homage to Catalonia (1938) —

Essays

Main article: Essays of George OrwellPenguin Books George Orwell: Essays, with an Introduction by Bernard Crick

- "The Spike" (1931) —

- "A Nice Cup of Tea" (1946) —

- "A Hanging" (1931) —

- "Shooting an Elephant" (1936) —

- "Charles Dickens" (1939) —

- "Boys' Weeklies" (1940) —

- "Inside the Whale" (1940) —

- "The Lion and The Unicorn: Socialism and the English Genius" (1941) —

- "Wells, Hitler and the World State" (1941) —

- "The Art of Donald McGill" (1941) —

- "Looking Back on the Spanish War" (1943) —

- "W. B. Yeats" (1943) —

- "Benefit of Clergy: Some notes on Salvador Dali" (1944) —

- "Arthur Koestler" (1944) —

- "Notes on Nationalism" (1945) —

- "How the Poor Die" (1946) —

- "Politics vs. Literature: An Examination of Gulliver's Travels" (1946) —

- "Politics and the English Language" (1946) —

- "Second Thoughts on James Burnham" (1946) —

- "Decline of the English Murder" (1946) —

- "Some Thoughts on the Common Toad" (1946) —

- "A Good Word for the Vicar of Bray" (1946) —

- "In Defence of P. G. Wodehouse" (1946) —

- "Why I Write" (1946) —

- "The Prevention of Literature" (1946) —

- "Such, Such Were the Joys" (1946) —

- "Lear, Tolstoy and the Fool" (1947) —

- "Reflections on Gandhi" (1949) —

- "Bookshop Memories" (1936) —

- "The Moon Under Water" (1946) —

- "Rudyard Kipling" (1942) —

- "Raffles and Miss Blandish" (1944) —

Poems

- "Romance"

- "A Little Poem"

- "Awake! Young Men of England"

- "Kitchener"

- "Our Minds are Married, But we are Too Young"

- "The Pagan"

- "The Lesser Evil"

- "Poem From Burma"

Source: George Orwell's Poems

About George Orwell

- Anderson, Paul (ed). Orwell in Tribune: 'As I Please' and Other Writings. Methuen/Politico's 2006. ISBN 1-842-75155-7

- Bowker, Gordon. George Orwell. Little Brown. 2003. ISBN 0-316-86115-4

- Buddicom, Jacintha. Eric & Us. Finlay Publisher. 2006. ISBN 0-9553708-0-9

- Caute, David. Dr. Orwell and Mr. Blair, Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 0-297-81438-9

- Crick, Bernard. George Orwell: A Life. Penguin. 1982. ISBN 0-14-005856-7

- Flynn, Nigel. George Orwell. The Rourke Corporation, Inc. 1990. ISBN 0-86593-018-X

- Hitchens, Christopher. Why Orwell Matters. Basic Books. 2003. ISBN 0-465-03049-1

- Hollis, Christopher. A Study of George Orwell: The Man and His Works. Chicago: Henry Regnery Co. 1956. ASIN B000ANO242.

- Larkin, Emma. Finding George Orwell in Burma. Penguin. 2005. ISBN 1-59420-052-1

- Lee, Robert A, Orwell's Fiction. University of Notre Dame Press, 1969. LC 74-75151

- Leif, Ruth Ann, Homage to Oceania. The Prophetic Vision of George Orwell. Ohio State U.P.

- Meyers, Jeffery. Orwell: Wintry Conscience of a Generation. W.W.Norton. 2000. ISBN 0-393-32263-7

- Newsinger, John. Orwell's Politics. Macmillan. 1999. ISBN 0-333-68287-4

- Shelden, Michael. Orwell: The Authorized Biography. HarperCollins. 1991. ISBN 0-06-016709-2

- Smith, D. & Mosher, M. Orwell for Beginners. 1984. London: Writers and Readers Publishing Cooperative.

- Taylor, D. J. Orwell: The Life. Henry Holt and Company. 2003. ISBN 0-8050-7473-2

- West, W. J. The Larger Evils. Edinburgh: Canongate Press. 1992. ISBN 0-86241-382-6 (Nineteen Eighty-Four – The truth behind the satire.)

- West, W. J. (ed.) George Orwell: The Lost Writings. New York: Arbor House. 1984. ISBN 0-87795-745-2

- Williams, Raymond, Orwell, Fontana/Collins, 1971

- Woodcock, George. The Crystal Spirit. Little Brown. 1966. ISBN 1-55164-268-9

See also

References

- "George Orwell". The Orwell Reader. Retrieved 2007-08-26.

- "George Orwell". History Guide. Retrieved 2007-08-26.

- Cite error: The named reference

obitwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - George Orwell, "Politics and the English Language," 1946

- Letter to Gleb Struve, 17th February 1944, Orwell: Essays, Journalism and Letters Vol 3, ed Sonia Brownell and Ian Angus

- Malcolm Muggeridge: Introduction

- http://www.hoover.org/publications/uk/2939606.html

- George Orwell: Rudyard Kipling

- "Orwell and the secret state: close encounters of a strange kind?", by Richard Keeble, Media Lens, Monday, October 10, 2005.

- Cyril Connolly Enemies of Promise 1938 ISBN0-233-97936-0

- Jacintha Buddicom Eric and Us Frewin 1974.

- George Orwell: A Life, Bernard Crick, p.480

- George Orwell: A Life, Bernard Crick, p.502

- George Orwell: A Life, Bernard Crick, p.504

- Michael Shelden Orwell: The Authorised Biography Heinnemann 1991

- T.R. Fyvel, A Case for George Orwell?, Twentieth Century, Sept. 1956, pp.257-8

External links

- George Orwell at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- George Orwell at IMDb

- The George Orwell Web Source - Essays, novels, reviews and exclusive images of Orwell.

- "Is Bad Writing Necessary?" - An essay comparing Theodor Adorno and George Orwell's lives and writing styles. In Lingua Franca, (December/January 2000).

- "Orwell's Burma", an essay in Time

- Orwell's Century, Think Tank Transcript

- Thesis statements and important quotes from the novel

- Films based on Orwell's novels from Internet Movie Database

- UK National Archives Reveal George Orwell watched by MI5

- Lesson plans for Orwell's works at Web English Teacher

- George Orwell at the Internet Book List

- 'George Orwell: International Socialist?' by Peter Sedgwick

- 'George Orwell: A literary Trotskyist?'

- George Orwell in the World of Science Fiction

- 'Collected Essays of George Orwell'

- Works of George Orwell

- Template:Worldcat id

- George Orwell in Lleida A photograph of a column of the POUM, including a man who appears to be Orwell, about 1936/37.

- George Orwell

- 1903 births

- 1950 deaths

- Administrators in British Burma

- British colonial police officers

- British people of the Spanish Civil War

- Deaths by tuberculosis

- English Anglicans

- English essayists

- English memoirists

- English novelists

- English poets

- English political writers

- English socialists

- Language creators

- Old Etonians

- Old Wellingtonians