This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Kaldari (talk | contribs) at 02:21, 5 January 2006 (rv. Image addition was also made during protection, by Curps. I actually just changed it back to the way it was originally protected. Regardless, I don't believe the policies are ambiguous on this.). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 02:21, 5 January 2006 by Kaldari (talk | contribs) (rv. Image addition was also made during protection, by Curps. I actually just changed it back to the way it was originally protected. Regardless, I don't believe the policies are ambiguous on this.)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| Part of a series on |

| Islam |

|---|

|

| Beliefs |

| Practices |

| History |

| Culture and society |

| Related topics |

The Qur'an (Template:ArL al-qur'ān, literally "the recitation"; also called Al Qur'ān Al Karīm or "The Noble Qur'an"; or transliterated Quran, Koran, and less commonly Alcoran) is the holy book of Islam. Muslims believe that the Qur'an is the literal word of God in Arabic and the culmination of God's revelation to mankind, revealed to Muhammad, the final prophet of Islam, over a period of 23 years through the angel Jibril (Gabriel).

Format of the Qur'an

The Qur'an consists of 114 suras (chapters) with a total of 6,236 ayat (verses) excluding 113 of the 114 sura-commencing bismillahs ("In the name of God, the Compassionate, the Merciful"), which are mostly considered as unnumbered. Alternatively, the figure may be reckoned as 6,348 ayat including these bismillahs; the exact number of ayat is disputed, not due to content disputes but due to different methods of counting. (A few "Quran-only" Muslims, having rejected two verses of the Qur'an as spurious, give the exact number as 6,346.) Muslims usually refer to the suras not by their numbers, but by an Arabic name derived in some way from the sura. (See List of sura names.) The suras are not arranged in chronological order (in the order in which Islamic scholars believe they were revealed) but in a different order, roughly by size, also believed by Muslims to be divinely inspired. After a short opening, the Qur'an proceeds to the longest sura, and closes with some of the shortest ones.

The Qur'an for reading and recitation

In addition to and largely independent of the division into suras, there are various ways of dividing the Qur'an into parts of approximately equal length for convenience in reading, recitation and memorization. The seven manazil (stations) and the thirty ajza' (parts) can be used to work through the entire Qur’an in a week or a month, one manzil or one juz' a day, respectively. A juz' is sometimes further divided into two ahzab (groups), and each ahzab is in turn subdivided into four quarters. A different structure is provided by the ruku'at, semantical units resembling paragraphs and comprising roughly ten ayat each.

A hafiz is one who has memorized the entire text of the Qur'an. There are believed to be millions of hafiz. Even Muslims who do not otherwise understand Arabic will memorize the Qur'an. All Muslims must memorize some parts of the Qu'ran in order to perform their daily prayers.

The language of the Qur'an

The Qur'an was one of the first texts written in Arabic. It is written in an early form of classical Arabic termed in English as “Quranic” Arabic. There are few other examples of Arabic from that time. (The Mu'allaqat, or Suspended Odes, are believed by some to be examples of pre-Islamic Arabic; others say that they were created after Muhammad. Only five pre-Islamic Arabic inscriptions survive.)

Soon after Muhammad's death in 632 CE, Islam burst out of Arabia and expanded to or conquered much of what was then the “civilized” world. Arab rulers had millions of foreign subjects, with whom they had to communicate. Thus, the language rapidly changed in response to this new situation, losing complexities of case and obscure vocabulary. Several generations after the prophet's death, many words used in the Qur'an had become opaque to ordinary sedentary Arabic-speakers, as Arabic had changed so much, so rapidly. The Bedouin speech changed at a considerably slower rate, however, and early Arabic lexicographers came to seek out Bedouin to explain difficult words or elucidate points of grammar. Partly in response to the religious need to explain the Qur'an to poorer speakers, Arabic grammar and lexicography soon became important sciences, and the model for the literary language remains to this day the speech used in Qur'anic times, rather than the current spoken dialects. Muslims contend that the Qur'an is remarkable for its poetry and grace, and that its very literary perfection is evidence of its divine origin. Since this perfection is apparent only to those who speak Arabic, this stands as one reason why only the original Arabic text is considered the real Qur’an. Translations are considered mere glosses, as interpretations - rather than the direct word - of God. The traditions governing the translation and publication of the Qur'an state that when the book is published, it should never simply be entitled "The Qur'an." The title should always include a defining adjective (avoiding conceivable confusion with other "recitations", in the Arabic sense), which is why most available editions of the Qur'an are titled The Glorious Qur'an, The Noble Qur'an, and other similar titles.

Translation of the Qur'an

Main article: Translation of the Qur'anThe Qur'an has been translated into many languages by well-known Islamic scholars. Each translation is a little different, showing the ability of the scholar to translate the text into a version that is both easy to understand and maintains the original meaning.

In English, scholars have sometimes favored archaic English words and constructions over their more modern or conventional equivalents; thus, for example, two widely-read translators, A. Yusuf Ali and M. Marmaduke Pickthall, use "ye" and "thou" instead of the more common "you." Another common stylistic decision has been to refrain from translating "Allah"---in Arabic, literally, "The God"---into the common English word "God." These choices may differ in more recent translations.

The wording styles are always changed in translations due to the different nature of the language that it is being translated into and Arabic. Therefore, translations of the Qur'an from Arabic to other languages are not considered by Muslims to be actual copies of the Qur'an, but rather are considered to be interpretive translations of the Qur'an; they are thus not given much weight in debates upon the Qur'an's meaning. In addition, as interpretive translations of the Qur'an rather than the original, they are treated more like ordinary books instead of being accorded the privileged status of Holy Books requiring special care.

Every reputable Islamic scholar is able, at the least, to read and understand the Qur'an in its original form, while most have it completely memorized.

Stylistic attributes

The Qur'an mixes narrative, exhortation, and legal prescription. The suras frequently combine all these modes, not always in ways that seem obvious to the reader, but ones that are generally explainable. Muslims often point out that the uniqueness of the Qur'anic style supports belief in its divine origin.

There are many repeated epithets (e.g. "Lord of the heavens and the earth"), sentences ("And when We said unto the angels: Prostrate yourselves before Adam, they fell prostrate, all save Iblis"), and even stories (such as the story of Adam) in the Qur'an. Muslim scholars explain these repetitions as emphasizing and explaining different aspects of important themes. Also, scholars and academics point out that English translation requires large changes in the wording in order to maintain the specific meaning and explanation.

The Qur'an is partly rhymed, partly prose. Traditionally, the Arabic grammarians consider the Qur'an to be a genre unique unto itself, neither poetry (defined as speech with metre and rhyme) nor prose (defined as normal speech or rhymed but non-metrical speech, saj').

The Qur'an often, although by no means always, uses loose rhyme between successive verses; for instance, at the beginning of surat al-Fajr:

- Wal-fajr(i),

- Wa layâlin `ashr(in),

- Wash-shaf`i wal-watr(i)

- Wal-layli 'idhâ yasr(î),

- Hal fî dhâlika qasamun li-dhî ḥijr(in).

or, to give a less loose example, the whole of surat al-Fil:

- 'A-lam tara kayfa fa`ala rabbuka bi-'aṣḥâbi l-fîl(i),

- 'A-lam yaj`al kaydahum fî taḍlîl(in)

- Wa-'arsala `alayhim ṭayran 'abâbîl(a)

- Tarmîhim bi-ḥijâratin min sijjîl(in)

- Fa-ja`alahum ka-`aṣfin ma'kûl(in).

(Note that verse-final vowels are unpronounced when the verses are enunciated separately, a regular pausal phenomenon in classical Arabic. In these cases, î and û often rhyme, and there is some scope for variation in syllable-final consonants.)

Some suras also include a refrain repeated every few verses, for instance ar-Rahman ("Then which of the favours of your Lord will ye deny?") and al-Mursalat ("Woe unto the repudiators on that day!").

Islamic scholars divide the verses of the Qur'an into those revealed at Mecca (Makka), and those revealed at Medina (Madina) after the Hijra. In general, the earlier Makkan suras tend to have shorter verses than the later Madinan suras, which deal with legal matters, and are quite long. Contrast the Makkan verses above with a verse such as al-Baqara 229:

- "A divorce is only permissible twice: after that, the parties should either hold Together on equitable terms, or separate with kindness. It is not lawful for you, (Men), to take back any of your gifts (from your wives), except when both parties fear that they would be unable to keep the limits ordained by Allah. If ye (judges) do indeed fear that they would be unable to keep the limits ordained by Allah, there is no blame on either of them if she give something for her freedom. These are the limits ordained by Allah. so do not transgress them if any do transgress the limits ordained by Allah, such persons wrong (Themselves as well as others)."

Similarly, the Madinan suras tend to be longer, including the longest sura of the Qur'an, al-Baqara.

The beginnings of the suras

Every chapter but one is preceded by the words Bismillah ir-Rahman ir-Rahim (listen). This is most frequently translated "In the Name of God, Most Gracious, Most Merciful." Interestingly, the Arabic words translated as "most gracious" (رحمان) and "most merciful" (رحيم) derive from the same root (RHM; ر ح م), or "mercy." Grammatically, the form of the first word conveys magnitude, while that of the second conveys permanence. Therefore, the chapter openings may better be translated as "In the name of God, the most merciful, the ever merciful." This double declaration at the start of most chapters suggests the importance of mercy in the Muslim conception of God.

Twenty-nine suras begin with letters taken from a restricted subset of the Arabic alphabet. Thus, for instance, surat Maryam begins

19:1 Kaf Ha Ya 'Ain Sad

19:2 (This is) a recital of the Mercy of thy Lord to His servant Zakariya."

While there has been some speculation on the meaning of these letters, many Muslim scholars believe that their full meaning may never be grasped. However, they have observed that in all but 4 of the 29 cases, these letters are almost immediately followed by mention of the Qur'anic revelation itself. Western scholars' efforts have been tentative; one proposal, for instance, was that they were initials or monograms of the scribes who had originally transcribed the sura. See Qur'anic initial letters for a fuller discussion.

The temporal order of Quranic verses

Belief in the Qur'an's direct, uncorrupted divine origin is considered fundamental to Islam by most Muslims. This of course entails believing that the Qur'an has neither errors nor inconsistencies.

- "This is the Book; in it is guidance sure, without doubt, to those who fear Allah" (Surat al-Baqarah, verse 2) .

However, there are instances where some verses presuppose that a given practice is allowed, while others forbid it. These are interpreted by most Muslim scholars in the light of the relative chronology of the verses: since the Qur'an was revealed over a course of 23 years, many verses were clarified or abrogated (mansūkh) by later verses. Many Muslim commentators explain that this is because Muhammad was directed to gradually lead his small band of believers towards the straight path, rather than reveal the full rigor of the law at once. For example, they argue that the prohibition of alcohol was accomplished gradually (over a period of approximately thirteen years) rather than immediately. The earliest verse tells the believers to ..."Approach not prayers with a mind befogged, until ye can understand all that ye say,-..." (4:43), a prohibition of drunkenness but not alcohol. Later verses expanded prohibition to all alcohol consumption: "They ask thee concerning wine and gambling. Say: "In them is great sin, and some profit, for men; but the sin is greater than the profit. ..." (2:219) .

Which verses abrogate which others, if any, is, however, a controversial matter.

Similarities between Quran & Bible

Main article: Similarities between the Bible and the Qur'anThe Qur'an retells stories of many of the people and events recounted in Jewish and Christian sacred books (Torah, Bible) and devotional literature (Apocrypha, Midrash), although it differs in many details. Well-known Biblical characters such as Adam, Noah, Abraham, Moses, Jesus, and John the Baptist are mentioned in the Qur'an as Prophets of Islam (For a complete list, see Similarities between the Bible and the Qur'an). Muslims account for differences between Quranic versions and Christian or Jewish texts (both of which are considered divine) by stating the Christian and Jewish texts have been corrupted and changed over time, and that the Qur'an preserves the correct version.

Origin and development of the Qur'an

This is a topic of some controversy, since Islamic scholars proceed with the assumption that the Qur'an is a divine and uncorrupted text, while most secular scholars and non-Muslim scholars are more skeptical.

According to Islamic scholars

Muhammad, according to tradition, could neither read nor write, but would simply recite what was revealed to him for his companions to write down and memorize. Adherents to Islam hold that the wording of the Qur'anic text available today corresponds exactly to that revealed to Muhammad himself: words of God delivered to Muhammad through the angel Jibril (Gabriel).

According to Muslim traditions, the companions of Muhammad began recording suras in writing before Muhammad died in 632; written copies of various suras during his lifetime are frequently alluded to in the traditions. For instance, in the story of the conversion of Umar ibn al-Khattab (when Muhammad was still at Mecca), his sister is said to have been reading a text of sura Ta-Ha. At Medina, about sixty-five companions are said to have acted as scribes for him at one time or another; the prophet would regularly call upon them to write down revelations immediately after they came.

One tradition has it that the first complete compilation of the Qur'an was made during the rule of the first caliph, Abu Bakr. Zayd ibn Thabit, who had been one of Muhammad's secretaries, "gathered the Qur'an from various parchments and pieces of bone, and from the chests (i.e. the memories) of men." This compilation was kept by Hafsa bint Umar, one of Muhammad's widows, as well as the daughter of Umar, the second caliph.

During the caliphate of Uthman ibn Affan, there were disputes about the recitation of the Qur'an. In response, Uthman decided to codify, standardize, and write down the text. Uthman is said to have commissioned a committee (including Zayd and several prominent members of Quraysh) to produce a standard copy of the text.

Some accounts say that this compilation was based on the text kept by Hafsa. Other stories say that Uthman made his compilation independently, Hafsa's text was brought forward, and the two texts were found to coincide perfectly. Still other accounts omit any reference to Hafsa.

Some Muslim scholars say that if the Qur'an had been collected by the order of a caliph, it would never have been relegated to the status of a keepsake for one of the prophet's widows. Possibly the story was invented to move the time of collection closer to Muhammad's death.

When the compilation was finished, sometime between 650 and 656 CE, Uthman sent out copies of it to the various corners of the Islamic empire. He ordered the destruction of all copies that differed from it.

Several manuscripts, including the Samarkand manuscript, are claimed to the original copies sent out by Uthman ; however, many scholars, Western and Islamic, doubt that any of the Uthmanic originals remain.

As for the copies that were destroyed, Islamic traditions say that Abdallah Ibn Masud, Ubay Ibn Ka'b, and Ali, Muhammad's son-in-law, had preserved versions that differed in some ways from the Uthmanic text that is now accepted by all Muslims. Muslim scholars record certain of the differences between the versions; those recorded consist almost entirely of orthographical and lexical variants, or different verse counts. All three (Ibn Masud, Ubay Ibn Ka'b, and Ali) are recorded as having accepted the Uthmanic text as authoritative.

Uthman's version was written in an older Arabic script that left out most vowel markings; thus the script could be interpreted and read in various ways. This basic Uthmanic script is called the rasm; it is the basis of several traditions of oral recitation, differing in minor points. In order to fix these oral recitations and prevent any mistakes, scribes and scholars began annotating the Uthmanic rasm with various diacritical marks -- dots and the like -- indicating how the word was to be pronounced. It is believed that this process of annotation began around 700 CE, soon after Uthman's compilation, and finished by approximately 900 CE. The Quran text most widely used today is based on the Hafs tradition of recitation, as approved by the eminent Al-Azhar University in Cairo in 1922. (For more information regarding traditions of recitations, see Quranic recitation, below.)

According to non-Muslim scholars

Some secular scholars accept something like the usual Islamic version, they say that Muhammad put forth verses and laws that he claimed to be of divine origin; that his followers memorized or wrote down his revelations; that numerous versions of these revelations circulated after his death in 632 CE, and that Uthman ordered the collection and ordering of this mass of material in the time period (650-656). These non-Islamic scholars point to many characteristics of the Qur'an -- the repetitions, the arbitrary order, the mixture of styles and genres -- as indicative of a human collection process that was extremely respectful of a miscellaneous collection of original texts.

Some other secular scholars are less willing to attribute the entire Qur'an to Muhammad, arguing that there is no real proof that the text of the Qur'an was collected under Uthman, since the earliest surviving copies of the complete Qur'an are centuries later than Uthman. (The oldest existing copy of the full text is from the ninth century .) They allege that Islam was formed slowly, over the centuries after the Muslim conquests, as the Islamic conquerors elaborated their beliefs in response to Jewish and Christian challenges. One influential proponent of this point of view was Dr. John Wansbrough, an English academic critic (since deceased). Wansbrough wrote in a dense, complex, almost hermetic style, and has had much more influence on Islamic studies through his students, Michael Cook and Patricia Crone, than he has through his own writings. In 1977 Crone and Cook published a book called Hagarism, which argued that,

- "The Qur'an is strikingly lacking in overall structure, frequently obscure and inconsequential in both language and content, perfunctory in its linking of disparate materials, and given to the repetition of whole passages in variant versions. On this basis it can plausibly be argued that the book is the product of belated and imperfect editing of materials from a plurality of traditions." (Patricia Crone and Michael Cook, Hagarism: The Making of the Islamic World, Cambridge, 1977, p. 18.)

Hagarism was extremely controversial at the time, as it challenged not only Muslim orthodoxy, but the prevailing attitudes among secular Islamicists. Crone and Cook have since retreated from their extreme claims that the Qur'an evolved over several centuries, but they still claim that the Sunni scholarly tradition is extremely unreliable, as it projects current Sunni orthodoxy onto the past -- much as if New Testament scholars were dedicated to proving that Jesus was a Presbyterian or a Methodist.

Fred Donner has argued against Crone and Cook, and for an early date for the collection of the Qur'an, based on his reading of the text itself. He points out that if the Qur'an had been collected over the tumultuous early centuries of Islam, with their vast conquests and expansion and bloody incidents between rivals for the caliphate, there would have been some evidence of this history in the text. However, there is nothing in the Qur'an that does not reflect what is known of the earliest Muslim community. (Narratives of Islamic Origins: The Beginnings of Islamic Historical Writing, Donner, Darwin Press, 1998, p. 60.)

Some claim that archaeological finds may also shed some light on the origins of the Qur'an. In 1972, during the restoration of the Great Mosque of San'a, in Yemen, laborers stumbled upon a "paper grave" containing tens of thousands of fragments of parchment on which verses of the Qur'an were written. (Qur'ans were and still are disposed thus, so as to avoid the impiety of treating the sacred text like ordinary garbage.) Some of these fragments were believed to be the oldest Quranic texts yet found. The European scholar Gerd-R. Puin has studied these fragments and published not only a corpus of texts, but some preliminary findings. The variations from the received text that he found seemed to match minor variations reported by some Islamic scholars, in their descriptions of the variant Qur'ans once held by Abdallah Ibn Masud, Ubay Ibn Ka'b, and Ali, and suppressed by Uthman's order ("Observations on Early Qur'an Manuscripts in San'a", Puin, in The Qur'an as Text, ed. Wild, Brill, 1996)

Skeptical scholars account for the many similarities between the Qur'an and the Jewish and Hebrew scriptures by saying that Muhammad was teaching what he believed a universal history, as he had heard it from the Jews and Christians he had encountered in Arabia and on his travels. These scholars also disagree with the Islamic belief that the whole of the Qur'an is addressed by God to humankind. They note that there are numerous passages where God is directly addressed, or mentioned in the third person, or where the narrator swears by various entities, including God.

Interpretation of the Qur'an

The Qur'an has sparked a huge body of commentary and explication. As discussed earlier, later Muslims did not always understand the Qur'an's Arabic, they did not catch allusions that were clear to early Muslims, and they were extremely concerned to reconcile apparent contradictions and conflicts in the Qur'an. Commentators glossed the Arabic, explained the allusions, and perhaps most importantly, decided which Quranic verses had been revealed early in Muhammad's prophetic career, as being appropriate to the very earliest Muslim community, and which had been revealed later, canceling out or "abrogating" (nāsikh) the earlier text. Memories of the occasions of revelation (asbāb al-nuzūl), the circumstances under which Muhammad had spoken as he did, were also collected, as they were believed to explain some apparent obscurities.

For all these reasons, it was extremely important for commentators to explain how the Qur'an was revealed -- when and under which circumstances. Much commentary, or tafsir, was dedicated to history. The early tafsir are considered to be some of the best sources for Islamic history. Famous early commentators include at-Tabari and Ibn Kathir.

(These classic commentaries usually include all common and accepted interpretations; modern fundamentalist commentaries like that written by Sayyed Qutb tend to advance only one of the possible interpretations.)

Commentators feel fairly sure of the exact circumstances prompting some verses, such as surat Iqra, or many parts, including ayat 190-194, of surat al-Baqarah. In other cases (eg surat al-Asr), the most that can be said is which city the Prophet was living in at the time (dividing between Makkan and Madinan suras.) In some cases, such as surat al-Kawthar, the details of the circumstances are disputed, with different traditions giving different accounts.

The most important external aid used in interpreting the meanings of the Qur'an are the hadith — the collected oral traditions upon which Muslim scholars (the ulema) based Islamic history and law. Scholars sifted the many thousands of hadith, trying to discover which were true and which were fabrications. One method, extensively used, was a study of the chain of narrators, the isnad, by which the tradition had been passed.

Note that, while certain hadith — the hadith qudsi — are claimed to record noncanonical words spoken by God to Muhammad, or the gist of them, Muslims do not consider these to form any part of the Qur'an.

'Created' vs. 'uncreated' Qur'an

The most widespread varieties of Muslim theology consider the Qur'an to be eternal and uncreated. Given that Muslims believe that Biblical figures such as Moses and Jesus all preached the same message as Islam, the doctrine of an unchanging, uncreated revelation implies that contradictions between the statements of the earlier divine revelations (the Torah and then the Bible), and the final revelation from God, the Qur'an, must be the result of human corruption of the earlier texts.

However, some Muslims have criticized the doctrine of an eternal Qur'an because it seemed to them that it diluted the doctrine of tawhid, or unity of God. Holding that the Qur'an is the eternal uncreated speech of Allah, speech that has always existed alongside Him, seemed to some thinkers to be a step in the direction of a more plural concept of God's nature (which could lead to what Muslims consider the sin of shirk, the association of something with God). Concerned that this interpretation appeared to echo the Christian concept of God's eternal Word or logos, some Muslims (notably the Mu'tazilis) rejected the notion of the Qur'an's eternality.

Some modern-day Muslim scholars touch on the doctrine of the eternal Qur'an when they question common conceptions of Islamic law. Reza Aslan has argued that such laws were created by God to meet the particular needs and circumstances of Muhammad's community. Likewise, Nasr Hamid Abu Zaid has claimed that the verses of the Qur'an that talk about Islamic law cannot be understood outside their historical context. This suggests that the Qur'an was in fact created in response to specific historical circumstances, and that it is not an eternal document containing rules applicable at all times and places.

Qur'an recitation

The very word Qur'an is usually translated as "recital," indicating that it cannot exist as a mere text. It has always been transmitted orally as well as textually.

To even be able to perform salat (prayer), a mandatory obligation in Islam, a Muslim is required to learn at least some suras of the Qur'an (typically starting with the first sura, al-Fatiha, known as the "seven oft-repeated verses," and then moving on to the shorter ones at the end).

A person whose recital repertoire encompasses the whole Qur'an is called a qari' (قَارٍئ) or hafiz (which translate as "reciter" or "memorizer," respectively). Muhammad is regarded as the first hafiz. Cantillation (tilawa تلاوة) of the Qur'an is a fine art in the Muslim world.

Schools of recitation

There are several schools of Quranic recitation, all of which are permissible pronunciations of the Uthmanic rasm. Today, ten canonical and at least four uncanonical recitations of the Qur'an exist. For a recitation to be canonical it must conform to three conditions:

- It must match the rasm, letter for letter.

- It must conform with the syntactic rules of the Arabic language.

- It must have a continuous isnad to Prophet Muhammad through tawatur, meaning that it has to be related by a large group of people to another down the isnad chain.

Ibn Mujahid documented seven such recitations and Ibn Al-Jazri added three. They are:

- Nafi` of Madina (169/785), transmitted by Warsh and Qaloon

- Ibn Kathir of Makka (120/737), transmitted by Al-Bazzi and Qonbul

- Ibn `Amer of Damascus (118/736), transmitted by Hisham and Ibn Zakwan

- Abu `Amr of Basra (148/770), transmitted by Al-Duri and Al-Soosi

- `Asim of Kufa (127/744), transmitted by Sho`bah and Hafs

- Hamza of Kufa (156/772), transmitted by Khalaf and Khallad

- Al-Kisa'i of Kufa (189/804), transmitted by Abul-Harith and Al-Duri

- Abu-Ja`far of Madina, transmitted by Ibn Wardan and Ibn Jammaz

- Ya`qoob of Yemen, transmitted by Ruways and Rawh

- Khalaf of Kufa, transmitted by Ishaaq and Idris

These recitations differ in the vocalization (tashkil تشكيل) of a few words, which in turn gives a complementary meaning to the word in question according to the rules of Arabic grammar. For example, the vocalization of a verb can change its active and passive voice. It can also change its stem formation, implying intensity for example. Vowels may be elongated or shortened, and glottal stops (hamzas) may be added or dropped, according to the respective rules of the particular recitation. For example, the name of archangel Gabriel is pronounced differently in different recitations: Jibrīl, Jabrīl, Jibra'īl, and Jibra'il. The name "Qur'ān" is pronounced without the glottal stop (as "Qurān") in one recitation, and prophet Ibrāhīm's name is pronounced Ibrāhām in another.

The more widely used narrations are those of Hafs (حفص عن عاصم), Warsh (ورش عن نافع), Qaloon (قالون عن نافع) and Al-Duri through Abu `Amr (الدوري عن أبي عمرو). Muslims firmly believe that all canonical recitations were recited by the Prophet himself, citing the respective isnad chain of narration, and accept them as valid for worshipping and as a reference for rules of Sharia. The uncanonical recitations are called "explanatory" for their role in giving a different perspective for a given verse or ayah. Today several dozen persons hold the title "Memorizer of the Ten Recitations," considered to be the ultimate honour in the sciences of Qur'an.

The Qur'an and Islamic culture

Before touching a copy of the Qur'an, or mushaf, a Muslim performs wudu (ablution or a ritual cleansing with water). This is based on tradition and a literal interpretation of sura 56:77-79: "That this is indeed a qur'an Most Honourable, In a Book well-guarded, Which none shall touch but those who are clean."

Qur'an desecration means insulting the Qur'an by defiling or dismembering it. Muslims must always treat the book with reverence, and are forbidden, for instance, to pulp, recycle, or simply discard worn-out copies of the text. Such books must be respectfully burned or buried . Respect for the written text of the Qur'an is an important element of religious faith by many Muslims. They believe that intentionally insulting the Qur'an is a form of blasphemy. According to the laws of some Muslim countries, blasphemy is punishable by lengthy imprisonment or even the death penalty.

- See also: Qur'an desecration by US military

Writing and printing the Qur'an

Most Muslims today use printed versions of the Qur'an. There are many editions, large and small, elaborate or plain, expensive or cheap. Bi-lingual forms with the Arabic on one side and a gloss into a more familiar language on the other are very popular.

The first printed Qur'an is said to have been published in 1801 in Kazan.

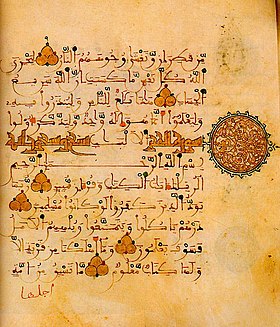

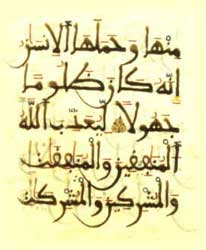

Before printing was widely adopted, the Qur'an was transmitted by copyists and calligraphers. Since Muslim tradition felt that directly portraying sacred figures and events might lead to idolatry, it was forbidden to decorate the Qur'an with pictures (as was often done for Christian texts, for example). Muslims instead lavished love and care upon the sacred text itself. Arabic is written in many scripts, some of which are both complex and beautiful. Arabic calligraphy is a highly honored art, much like Chinese calligraphy. Muslims also decorated their Qur'ans with abstract figures (arabesques), colored inks, and gold leaf. Pages from some of these beautiful antique Qur'ans are displayed throughout this article.

Qur'ans were also produced in many different sizes, from extremely large Qur'ans that were displayed in mosques, to extremely small Qur'ans intended for personal use.

Some Muslims believe that it is not only acceptable, but commendable to decorate everyday objects with Quranic verses, as daily reminders. Other Muslims feel that this is a misuse of Quranic verses; those who handle these objects will not have cleansed themselves properly and may use them without respect.

See also

Literature

- A. J. Arberry, The Koran Interpreted, Touchstone Books, 1996. ISBN 0684825074

- M. M. Al-Azami, The History of the Qur'anic Text from Revelation to Compilation, UK Islamic Academy: Leicester 2003.

- Muhammad ibn Jarir al-Tabari, Jami al-bayan `an ta'wil al-Qur'an, Cairo 1955-69, transl. J. Cooper (ed.), The Commentary on the Qur'an, Oxford University Press, 1987. ISBN 0199201420

- Ibn Warraq (ed.), The Origins of the Koran, Prometheus Books, 1998. ISBN 157392198X

- J. D. McAuliffe (ed.), Encyclopaedia of the Qur'an, Brill, 2002-2004.

- Fazlur Rahman, Major Themes in the Qur'an, Bibliotheca Islamica, 1989. ISBN 0882970461

- Robinson, Neal, Discovering the Qur'an, Georgetown University Press, 2002. ISBN 1589010248

- W. M. Watt and R. Bell, Introduction to the Qur'an, Edinburgh University Press, 2001. ISBN 0748605975

- Jane Dammen McAuliffe, Quranic Christians : An Analysis of Classical and Modern Exegesis, Cambridge University Press, 1991. ISBN 0521364701

- Barbara Freyer Stowasser, Women in the Qur'an, Traditions, and Interpretation, Oxford University Press; Reprint edition (June 1, 1996), ISBN 0195111486

- Helmut Gatje, Alford T. Welch, The Qur'an and Its Exegesis, Oneworld Publications; New Ed edition (November 1, 1996). ISBN 1851681183

- Hanna E. Kassis, A Concordance of the Qur'an, University of California Press (March 1, 1984), ISBN 0520043278

- Sells, Michael, "Approaching the Qur'an: The Early Revelations," White Cloud Press, Book & CD edition (November 15, 1999). ISBN 1883991269

External links

Translations

- Quran in Arabic— Read Quran in Arabic (pdf format)

- Translation of Quran in English— Read Quran in English (pdf format)

- Translation of Quran in Urdu— Read Quran in Urdu (pdf format)

- The Noble Qur'an — three translations (Yusuf Ali, Shakir, and Pickthal). Also, Sayyid Abul Ala Maududi's chapter introductions to the Qur'an

- The Holy Qur'an — Translated by a team of Muslim scholars including the first woman to translate the Qur'an into English.

- The Noble Qur'an — Translated by Dr.Muhammad Taqi-ud-Din Al Hilali, and Dr. Muhammad Muhsin Khan. A well-known English translation endorsed by the Saudi government. Includes Arabic commentary by Ibn Katheer, Tabari, and Qurtubi.

- The Final Testament — Translation by Rashad Khalifa, considered heretic and an apostate by the main corpus of Muslims.

- Qur'anic Recitation with English Translation by Qari Muhammad Ayub, Spoken in English by J.D. Hall

- Exposition of the Holy Qur'an — by G. A. Parwez

- The Qur'an As It Explains Itself — by The QXP Project

- Holy Qur'an Resources on the Internet — comprehensive online Qur'anic resource portal

- itsIslam.net - Quran Translation - English Quran Reference and Audios with Arabic-Urdu Translation

- The Message - Free Minds / Progressive Muslims - A literal translation of the holy Quran

References

Search

- Qur'an Search Search English, Turkish, French, Spanish, Malay, German

- Qur'an Search or browse the English Shakir translation

- The Qur'an Browser

- Quran knowledge sources

- Qur'an Database

- King Fahd Complex For The Printing Of The Holy Qur'an (in Arabic, English, French, Urdu, Spanish, Indonesian and Hausa)

- islamawakened Ayat-by-ayat transliteration and parallel translations from eleven prominent translators

- Quranbrowser Browse and Compare Quran Translations

- al-islam

- muslim-webSearch Quran in Arabic & recitation

- Texts of Islam

Tafsir (Commentary)

- Overview of Tafsir

- Tafsir by Ibn Kathir

- The Message of the Qur'an Translated and Explained by Muhammad Asad

- Tafsir Al-Mizan by Allamah Tabatabai

- Tafheem-ul-Quran by Maula Maududi

- Quran in XML

- Study The Quran in-depth

- Audio Tafseer of selected Chapters of Quran

Ulum (Qur'anic studies)

- Ilm ul Qur'an — by Hasanuddin Ahmad

- The Easy Dictionary of the Qur'an Compiled By Shaikh AbdulKarim Parekh

- Four Basic Quranic Terms by Maula Maududi

- Way To The Quran by Khurrum Murad

Audio/Video

- Complete Qur'an recitations by 271 different reciters

- Four videos of recitation, commentary, or prayer

- English Reading

- AlQuranic.com

Academic discussion of the origins of the Qur'an

- W. M. Watt´s "Bell´s Introduction to the Qur'an" (online version)

- Die syro-aramaeische Lesart des Koran; Ein Beitrag zur Entschlüsselung der Qur?ansprache Review of Christoph Luxenberg's book

- Die syro-aramäische Lesart des Koran: Ein Beitrag zur Entschlüsselung der Koransprache Another Review by François de Blois, Journal of Qur'anic Studies, 2003, Volume V, Issue 1

- What is the Koran? The Atlantic Online

Supporting views regarding Islamic traditions and the Qur'an

- Koran and Nature's Testimony Articles and Books by Muhammad Asadi.

- Examining The Qur'an Original articles responding to textual criticism.

- The Qur'anic Studies

- The Bible, the Qur'an and Science by Dr. Maurice Bucaille

- Is the Qur'an the Word of God? A video debate between Muslim/Christian apologists

- The Authenticity of the Qur'an A video debate between Muslim/Christian apologists

- Who Wrote the Qur'an? Analysis of the various theories from an Islamic viewpoint.

- Free Books on Various Topics and Deabtes Verbatim Scripts of Dr. Zakir Naik's Lectures And Debates

- Approaching Qur'an and Sunnah - Classical, Traditional and Progressive Methodologies

Skeptical views of Islamic traditions and the Qur'an

- Textual Variants of the Qur'an

- The Skeptic's Annotated Qur'an — a version of the Qur'an annotated from a skeptical point of view.

- Radical New Views of Islam and the Origins of the Koran

- The Origins of the Koran