This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Cold Season (talk | contribs) at 20:18, 6 December 2011 (Undid revision 464327594 by 202.137.119.66 (talk)). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 20:18, 6 December 2011 by Cold Season (talk | contribs) (Undid revision 464327594 by 202.137.119.66 (talk))(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)

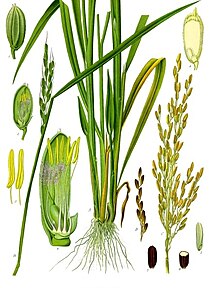

| Oryza sativa | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Angiosperms |

| Class: | Monocots |

| Order: | Poales |

| Family: | Poaceae |

| Genus: | Oryza |

| Species: | O. sativa |

| Binomial name | |

| Oryza sativa L. | |

Oryza sativa, commonly known as Asian rice, is the plant species most commonly referred to in English as rice. Oryza sativa is the cereal with the smallest genome, consisting of just 430Mb across 12 chromosomes. It is renowned for being easy to genetically modify, and is a model organism for cereal biology.

Classification

Oryza sativa contains two major subspecies: the sticky, short grained japonica or sinica variety, and the non-sticky, long-grained indica variety. Japonica are usually cultivated in dry fields, in temperate East Asia, upland areas of Southeast Asia and high elevations in South Asia, while indica are mainly lowland rices, grown mostly submerged, throughout tropical Asia. Rice is known to come in a variety of colors, including: white, brown, black, purple, and red.

A third subspecies, which is broad-grained and thrives under tropical conditions, was identified based on morphology and initially called javanica, but is now known as tropical japonica. Examples of this variety include the medium grain 'Tinawon' and 'Unoy' cultivars, which are grown in the high-elevation rice terraces of the Cordillera Mountains of northern Luzon, Philippines.

Glaszmann (1987) used isozymes to sort Oryza sativa into six groups: japonica, aromatic, indica, aus, rayada, and ashina.

Garris et al. (2004) used SSRs to sort Oryza sativa into five groups; temperate japonica, tropical japonica and aromatic comprise the japonica varieties, while indica and aus comprise the indica varieties.

Nomenclature and taxonomy

B: Brown rice

C:Rice with germ

D: White rice with bran residue

E:Musenmai (Japanese:無洗米), "Polished and ready to boil rice", literally, non-wash rice

(1):Chaff

(2):Bran

(3):Bran residue

(4):Cereal germ

(5):Endosperm

| This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (December 2009) |

List of the cultivars

- Indica (long grain)

- Japonica (short grain)

| This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (December 2009) |

History of domestication and cultivation

Origins

There have been plenty of debates on the origins of the domesticated rice. However, in 2011, a combined effort by Stanford University, New York University, Washington University, and Purdue University has provided conclusive evidence that domesticated rice has a single origin in the Yangtze Valley of China.

The precise date of the first domestication is unknown, but depending on the molecular clock estimate used by the scientists, the date is estimated to be 8,200 to 13,500 years ago. This is consistent with known archaeological data on the subject.

Earlier debates

Based on one chloroplast and two nuclear gene regions, Londo et al. (2006) concluded Oryza sativa rice was domesticated at least twice—indica in eastern India, Myanmar and Thailand; and japonica in southern China and Vietnam—though they concede that there is archaeological and genetic evidence for a single domestication of rice in the lowlands of China. (See "Origins" section directly above for the latest updates)

Because the functional allele for nonshattering, the critical indicator of domestication in grains, as well as five other single nucleotide polymorphisms, is identical in both indica and japonica, Vaughan et al. (2008) determined there was a single domestication event for Oryza sativa in the region of the Yangtze river valley.

Continental East Asia

Rice appears to have been used by the early Neolithic populations of Lijiacun and Yunchanyan. Evidence of possible rice cultivation in China from c. 11,500 BP has been found, however it is still questioned whether the rice was indeed being cultivated, or instead being gathered as wild rice. Bruce Smith, an archaeologist at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., who has written on the origins of agriculture, says that evidence has been mounting that the Yangtze was probably the site of the earliest rice cultivation.

Zhao (1998) argues that collection of wild rice in the Late Pleistocene had, by 6400 BC, led to the use of primarily domesticated rice. Morphological studies of rice phytoliths from the Diaotonghuan archaeological site clearly show the transition from the collection of wild rice to the cultivation of domesticated rice. The large number of wild rice phytoliths at the Diaotonghuan level dating from 12,000–11,000 BP indicates that wild rice collection was part of the local means of subsistence. Changes in the morphology of Diaotonghuan phytoliths dating from 10,000–8,000 BP show that rice had by this time been domesticated. Analysis of Chinese rice residues from Pengtoushan, which were carbon 14 dated to 8200–7800 BCE, show that rice had been domesticated by this time.

In 1998, Crawford and Shen reported the earliest of 14 AMS or radiocarbon dates on rice from at least nine Early to Middle Neolithic sites is no older than 7000 BC, that rice from the Hemudu and Luojiajiao sites indicates that rice domestication likely began before 5000 BC, but that most sites in China from which rice remains have been recovered are younger than 5000 BC.

South Asia

Wild Oryza rice appeared in the Belan and Ganges valley regions of northern India as early as 4530 BC and 5440 BC, respectively, although many believe it may have appeared earlier. The Encyclopedia Britannica—on the subject of the first certain cultivated rice—holds that:

Denis J. Murphy (2007) further details the spread of cultivated rice from India into Southeast Asia:

Rice was cultivated in the Indus Valley Civilization. Agricultural activity during the second millennium BC included rice cultivation in the Kashmir and Harrappan regions. Mixed farming was the basis of Indus valley economy.

Punjab is the largest producer and consumer of rice in India.

Korean peninsula and Japanese archipelago

Mainstream archaeological evidence derived from palaeoethnobotanical investigations indicate dry-land rice was introduced to Korea and Japan some time between 3500 and 1200 BC. The cultivation of rice in Korea and Japan during that time occurred on a small-scale, fields were impermanent plots, and evidence shows that in some cases domesticated and wild grains were planted together. The technological, subsistence, and social impact of rice and grain cultivation is not evident in archaeological data until after 1500 BC. For example, intensive wet-paddy rice agriculture was introduced into Korea shortly before or during the Middle Mumun Pottery Period (c. 850–550 BC) and reached Japan by the final Jōmon or initial Yayoi periods c. 300 BC.

In 2003, Korean archaeologists alleged they discovered burnt grains of domesticated rice in Soro-ri, Korea, which dated to 13,000 BC. These predate the oldest grains in China, which were dated to 10,000 BC, and potentially challenge the mainstream explanation that domesticated rice originated in China. The findings were received by academia with strong skepticism, and the results and their publicizing has been cited as being driven by a combination of nationalist and regional interests.

Southeast Asia

Rice is the staple for all classes in contemporary Southeast Asia, from Myanmar to Indonesia. In Indonesia, evidence of wild Oryza rice on the island of Sulawesi dates from 3000 BCE. The evidence for the earliest cultivation, however, comes from eighth-century stone inscriptions from Java, which show kings levied taxes in rice. Divisions of labor between men, women, and animals that are still in place in Indonesian rice cultivation, can be seen carved into the ninth-century Prambanan temples in Central Java. In the 16th century, Europeans visiting the Indonesian islands saw rice as a new prestige food served to the aristocracy during ceremonies and feasts. Rice production in Indonesian history is linked to the development of iron tools and the domestication of water buffalo for cultivation of fields and manure for fertilizer. Once covered in dense forest, much of the Indonesian landscape has been gradually cleared for permanent fields and settlements as rice cultivation developed over the last 1500 years.

In the Philippines, the greatest evidence of rice cultivation since ancient times can be found in the Cordillera Mountain Range of Luzon in the provinces of Apayao, Benguet, Mountain Province and Ifugao. The Banaue Rice Terraces (Tagalog: Hagdan-hagdang Palayan ng Banaue) are 2,000 to 3,000-year-old terraces that were carved into the mountains by ancestors of the Batad indigenous people. It is commonly thought that the terraces were built with minimal equipment, largely by hand. The terraces are located approximately 1,500 meters (5,000 ft) above sea level and cover 10,360 square kilometers (about 4,000 square miles) of mountainside. They are fed by an ancient irrigation system from the rainforests above the terraces. It is said that if the steps are put end to end it would encircle half the globe. The Rice Terraces (a UNESCO World Heritage Site) are commonly referred to by Filipinos as the "Eighth Wonder of the World".

Evidence of wet rice cultivation as early as 2200 BC has been discovered at both Ban Chiang and Ban Prasat in Thailand.

By the 19th century, encroaching European expansionism in the area increased rice production in much of Southeast Asia, and Thailand, then known as Siam. British Burma became the world's largest exporter of rice, from the turn of the 20th century to the 1970s, when neighbouring Thailand exceeded Burma.

See also

- International Code of Nomenclature for Cultivated Plants

- Traceability of genetically modified organisms

- Oryza glaberrima

References

- Oka (1988)

- CECAP, PhilRice and IIRR. 2000. “Highland Rice Production in the Philippine Cordillera.”

- Glaszmann, J. C. (2004). "Isozymes and classification of Asian rice varieties". Theoretical and Applied Genetics.

- Garris; Tai, TH; Coburn, J; Kresovich, S; McCouch, S; et al. (2004). "Genetic structure and diversity in Oryza sativa L." Genetics. 169 (3): 1631–8. doi:10.1534/genetics.104.035642. PMC 1449546. PMID 15654106.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Lapitan, Victoria C.; Redoña, Edilberto D.; Abe, Toshinori; Brar, Darshan S.; et al. (2009). "Molecular characterization and agronomic performance of DH lines from the F1 of indica and japonica cultivars of rice (Oryza sativa L.)". Field Crops Research. 112 (2–3): 222–8. doi:10.1016/j.fcr.2009.03.008.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|first=(help) - http://www.sciencenewsline.com/biology/2011050313000047.html

- http://www.pnas.org/content/early/2011/04/27/1104686108.short

- Londo JP, Chiang YC, Hung KH, Chiang TY, Schaal BA (2006). "Phylogeography of Asian wild rice, Oryza rufipogon, reveals multiple independent domestications of cultivated rice, Oryza sativa". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103 (25): 9578–83. doi:10.1073/pnas.0603152103. PMC 1480449. PMID 16766658.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Vaughan; Lu, B; Tomooka, N; et al. (2008). "The evolving story of rice evolution". Plant Science. 174 (4): 394–408. doi:10.1016/j.plantsci.2008.01.016.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Crawford and Shen 1998

- Harrington, Spencer P.M. (June 11, 1997). "Earliest Rice". Archaeology. Archaeological Institute of America.

Rice cultivation began in China ca. 11,500 years ago, some 3,500 years earlier than previously believed

- Normile, Dennis (1997). "Yangtze seen as earliest rice site". Science. 275 (5298): 309–310. doi:10.1126/science.275.5298.309.

- Zhao, Z. (1998). "The Middle Yangtze Region in China is the Place Where Rice was Domesticated: Phytolithic Evidence from the Diaotonghuan Cave, Northern Jiangxi". Antiquity. 72 (278): 885–897.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - MacNeish R. S. and Libby J. eds. (1995) Origins of Rice Agriculture. Publications in Anthropology No. 13.

- The Formation of Chinese Civilization (2005), pp. 298

- ^ Smith, C. Wayne (2000). Sorghum: Origin, History, Technology, and Production. John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 0471242373.

- "rice". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica. 2008.

- Murphy, Denis J. (2007). People, Plants and Genes: The Story of Crops and Humanity. Oxford University Press. p. 178. ISBN 0-19-920713-5.

- ^ Kahn, Charles (2005).World History: Societies of the Past. Portage & Main Press. 92. ISBN 1553790456.

- Crawford, G.W. and G.-A. Lee. (2003). "Agricultural Origins in the Korean Peninsula". Antiquity. 77 (295): 87–95.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Cf. BBC news (2003)

- Kim, Minkoo (2008). "Multivocality, Multifaceted Voices, and Korean Archaeology". Evaluating Multiple Narratives: Beyond Nationalist, Colonialist, Imperialist Archaeologies. New York: Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-76459-7.

- Taylor, Jean Gelman (2003). Indonesia: Peoples and Histories. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. pp. 8–9. ISBN 0-300-10518-5.