This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Dominus Vobisdu (talk | contribs) at 12:22, 1 July 2012 (Do not edit war. You must get consensus BEFORE making changes on this scale to a controversial article.). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 12:22, 1 July 2012 by Dominus Vobisdu (talk | contribs) (Do not edit war. You must get consensus BEFORE making changes on this scale to a controversial article.)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "History of astrology" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (July 2011) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| Astrology |

|---|

|

| Background |

| Traditions |

| Branches |

| Astrological signs |

| Symbols |

Astrology, the belief in a connection between the cosmos and terrestrial matters has played an important part in human history.

Regional branches of astrology include Western astrology, Indian astrology, and Chinese or East Asian astrology.

Early origins

Astrology, in its broadest sense, is the search for meaning in the sky. It has therefore been argued that astrology began as a study as soon as human beings made conscious attempts to measure, record, and then predict, seasonal changes by reference to astronomical cycles.

Early evidence of such practices appears as markings on bones and cave walls, which show that lunar cycles were being noted as early as 25,000 years ago; the first step towards recording the Moon’s influence upon tides and rivers, and towards organizing a communal calendar. Agriculture needs were also met by increasing knowledge of constellations, whose appearances change with the seasons, allowing the rising of particular star-groups to herald annual floods or seasonal activities. By the third millennium BCE, widespread civilizations had developed sophisticated awareness of celestial cycles, and are believed to have consciously oriented their temples to create alignment with the heliacal risings of the stars.

There is scattered evidence to suggest that the oldest known astrological references are copies of texts made during this period. Two, from the Venus tablet of Ammisaduqa (compiled in Babylon round 1700 BCE) are reported to have been made during the reign of king Sargon of Akkad (2334-2279 BCE). Another, showing an early use of electional astrology, is ascribed to the reign of the Sumerian ruler Gudea of Lagash (ca. 2144-2124 BCE). This describes how the gods revealed to him in a dream the constellations that would be most favourable for the planned construction of a temple. However, controversy attends the question of whether they were genuinely recorded at the time or merely ascribed to ancient rulers by posterity. The oldest undisputed evidence of the use of astrology as an integrated system of knowledge is therefore attributed to the records that emerge from the first dynasty of Mesopotamia (1950-1651 BC).

Mundane astrology

| This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (April 2012) |

Mundane astrology is the application of astrology to world affairs and world events, taking its name from the Latin word mundus, meaning "the World". It is widely believed by astrological historians to be the most ancient branch of astrology. Astrological practices of divination and planetary interpretation have been used for millennia to address political questions. It was, however, only with the gradual emergence of horoscopic astrology from the sixth century B.C. that astrology developed into two distinct branches, mundane astrology and natal astrology.

Ancient world

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (August 2008) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Europe and the Middle East exchanged astrological theories and continually influenced each other. Bouché-Leclercq, Cumont and Boll hold that the middle of the 4th century BC is when Babylonian astrology began to firmly enter western culture.

This spread of astrology was coincident with the rise of a scientific phase of astronomy in Babylonia. This may have weakened to some extent the hold that astrology had on the priests and the people . Another factor leading to the decline of the old faith in the Euphrates Valley may have been the advent of the Persians, who brought with them a religion which differed markedly from the Babylonian-Assyrian polytheism (see Zoroastrianism).

Babylonia

Main article: Babylonian astrologyThe history of astrology can be traced back to the earliest phases of Babylonian history, in the third millennium BCE.

In Babylonia as well as in Assyria as a direct offshoot of Sumerian culture (or in general the "Mesopotamian" culture), astrology takes its place in the official cult as one of the two chief means at the disposal of the priests (who were called bare or "inspectors") for ascertaining the will and intention of the gods, the other being through the inspection of the liver of the sacrificial animal (see omen).

The earliest extant collection of Babylonian astrology texts are known collectively as Enuma Anu Enlil (literally meaning "When the gods Anu and Enlil..."). These date back at least to the middle of the second millennium BCE. The collection groups together omens and 'signs' drawn from celestial, meteorological and calendrical significations, which are interpreted for their relevancy to national and political affairs. In this the Moon's cycle held special significance. For example, a segment of the text reads: "These are the oracles when Sin (i.e., the moon) makes a decision, the great gods of heaven and earth decide the doings of mankind ... eclipse, flood, illness, death, the great gallu-demons, Sebettu always block the way of the Sun".

Theory of divine government

Just as the sacrificial method of divination rested on a well-defined theory – to wit, that the liver was the seat of the soul of the animal and that the deity in accepting the sacrifice identified himself with the animal, whose "soul" was thus placed in complete accord with that of the god and therefore reflected the mind and will of the god – so astrology is sometimes purported to be based on a theory of divine government of the world.

Starting with the view that man's life and happiness are largely dependent upon phenomena in the heavens, that the fertility of the soil is dependent upon the sun shining in the heavens as well as upon the rains that come from heaven; and that, on the other hand, the mischief and damage done by storms and floods (both of which the Euphratean Valley was almost regularly subject to), were to be traced likewise to the heavens – the conclusion was drawn that all the great gods had their seats in the heavens.

Gods and planets

In Mesopotamian astrology planet-names reflected association with dominant deities. For example, the basic association of the planet Mars was with the ill-boding war-god Nergal, by which it was referred to as the ‘star of Nergal’. Likewise the basic association of Saturn was with the destructive god Ninurta, Jupiter the creative god Marduk, Venus the fertility goddess Ishtar, Mercury the scribe god Nabu, the Sun the revealing god Shamash, and the Moon the measuring god Sin.

The movements of the sun, moon and five planets were regarded as representing the activity of the five gods in question, together with the moon-god Sin and the sun-god Shamash, in preparing the occurrences on earth. If, therefore, one could correctly read and interpret the activity of these powers, one knew what the gods were aiming to bring about.

The influence of Babylonian planetary lore appears also in the assignment of the days of the week to the planets, for example Sunday, assigned to the sun, and Saturday, the day of Saturn.

System of interpretation

The Babylonian priests applied themselves to perfecting an interpretation of the phenomena to be observed in the heavens, and it was natural that the system was extended from the moon, sun and five planets to the stars.

The interpretations themselves were based (as in the case of divination through the liver) chiefly on two factors:

- On the recollection or on written records of what in the past had taken place when the phenomenon or phenomena in question had been observed, and

- Association of ideas – involving sometimes merely a play upon words – in connection with the phenomenon or phenomena observed.

Thus, if on a certain occasion, the rise of the new moon in a cloudy sky was followed by victory over an enemy or by abundant rain, the sign in question was thus proved to be a favorable one and its recurrence would thenceforth be regarded as an omen for good fortune of some kind to follow. On the other hand, the appearance of the new moon earlier than was expected was regarded as unfavorable, as it was believed that anything appearing prematurely suggested an unfavorable occurrence.

In this way a mass of traditional interpretation of all kinds of observed phenomena was gathered, and once gathered became a guide to the priests for all times.

Limitations of early knowledge

Astrology in its earliest stage was marked by three characteristics:

- In the first place, In Babylonia and Assyria the interpretation of the movements and position of the heavenly bodies were centered largely and indeed almost exclusively in the public welfare and the person of the king, because upon his well-being and favor with the gods the fortunes of the country were dependent . The ordinary individual's interests were not in any way involved, and many centuries had to pass beyond the confines of Babylonia and Assyria before that phase is reached, which in medieval and modern astrology is almost exclusively dwelt upon – the individual horoscope.

- In the second place, the astronomical knowledge presupposed and accompanying early Babylonian astrology was, being of an empirical character, limited and flawed. The theory of the ecliptic as representing the course of the sun through the year, divided among twelve constellations with a measurement of 30° to each division, is of Babylonian origin, as has now been definitely proved; but it does not appear to have been perfected until after the fall of the Babylonian empire in 539 BC. The defectiveness of early Babylonian astronomy may be gathered from the fact that as late as the 6th century BC an error of almost an entire month was made by the Babylonian astronomers in the attempt to determine through calculation the beginning of a certain year. For a long time the rise of any serious study of astronomy did not go beyond what was needed for the purely practical purposes that the priests as "inspectors" of the heavens (as they were also the "inspectors" of the sacrificial livers) had in mind.

- In the third place, we have, probably as early as the days of Khammurabi, i.e. c. 2000 BC, the combination of prominent groups of stars with outlines of pictures fantastically put together, but there is no evidence that prior to 700 BC more than a number of the constellations of our zodiac had become part of the current astronomy.

Hellenistic world

Main article: Hellenistic astrologyAfter the occupation by Alexander the Great in 332BC, Egypt came under Greek rule and influence, and it was in Alexandrian Egypt where horoscopic astrology first appeared. The endeavor to trace the horoscope of the individual from the position of the planets and stars at the time of birth represents the most significant contribution of the Greeks to astrology. This system can be labeled as "horoscopic astrology" because it employed the use of the ascendant, otherwise known as the horoskopos in Greek.

The system was carried to such a degree of perfection that later ages made but few additions of an essential character to the genethlialogy or drawing up of the individual horoscope by the Greek astrologers. Particularly important in the development of horoscopic astrology was the astrologer and astronomer Ptolemy, whose work, the Tetrabiblos laid the basis of the Western astrological tradition. Under the Greeks and Ptolemy in particular, the planets, Houses, and Signs of the zodiac were rationalized and their function set down in a way that has changed little to the present day. Ptolemy's work on astronomy was the basis of Western teachings on the subject for the next 1,300 years.

To the Greek astronomer Hipparchus belongs the credit of the discovery (c. 130 BC) of the theory of the precession of the equinoxes, for a knowledge of which among the Babylonians we find no definite proof.

Babylonia or Chaldea was so identified with astrology that "Chaldaean wisdom" became among Greeks and Romans the synonym of divination through the planets and stars, and it is perhaps not surprising that in the course of time to be known as a "Chaldaean" carried with it frequently the suspicion of charlatanry and of more or less willful deception.

Astrology in Egypt developed under the Ptolemies after the conquest of Egypt by Alexander the Great.

Astrology and the sciences

Partly in further development of views unfolded in Babylonia, but chiefly under Greek influences, the scope of astrology was enlarged until it was brought into connection with practically all of the known sciences: botany, chemistry, zoology, mineralogy, anatomy and medicine. Colours, metals, stones, plants, drugs and animal life of all kinds were each associated with one or another of the planets and placed under their rulership.

By this process of combination, the entire realm of the natural sciences was translated into the language of astrology with the purpose of seeing in all phenomena signs indicative of what the future had in store.

The fate of the individual led to the association of the planets with parts of the body and so with Medical astrology. .

From the planets the same association of ideas was applied to the constellations of the zodiac . The zodiac came to be regarded as the prototype of the human body, the different parts of which all had their corresponding section in the zodiac itself. The head was placed in the first sign of the zodiac, Aries, the Ram; and the feet in the last sign, Pisces, the Fishes. Between these two extremes the other parts and organs of the body were distributed among the remaining signs of the zodiac. In later phases of astrology the signs of the zodiac are sometimes placed on a par with the planets themselves, so far as their importance for the individual horoscope is concerned.

With human anatomy thus connected with the planets, with constellations, and with single stars, medicine became an integral part of astrology. Diseases and disturbances of the ordinary functions of the organs were attributed to the influences of planets, constellations and stars.

Islamic world

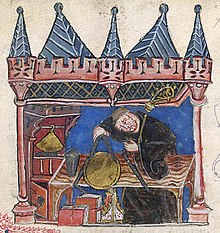

| Abū Maʿshar | |

|---|---|

A Latin translation of Abū Maʿshar's De Magnis Coniunctionibus ("Of the great conjunctions"), Venice, 1515. A Latin translation of Abū Maʿshar's De Magnis Coniunctionibus ("Of the great conjunctions"), Venice, 1515. | |

| Born | c. 787 Balkh, Khurasan |

| Died | c. 886 Wāsiṭ, Iraq |

| Academic background | |

| Influences | Aristotle, al-Kindi |

| Academic work | |

| Era | Islamic Golden Age |

| Main interests | Astrology, Astronomy |

| Influenced | Al-Sijzi, Albertus Magnus, Roger Bacon, Pierre d'Ailly, Pico della Mirandola. |

Astrology was taken up enthusiastically by Islamic scholars following the collapse of Alexandria to the Arabs in the 7th century, and the founding of the Abbasid empire in the 8th. The second Abbasid caliph, Al Mansur (754-775) founded the city of Baghdad to act as a centre of learning, and included in its design a library-translation centre known as Bayt al-Hikma ‘Storehouse of Wisdom’, which continued to receive development from his heirs and was to provide a major impetus for Arabic-Persian translations of Hellenistic astrological texts. The early translators included Mashallah, who helped to elect the time for the foundation of Baghdad, and Sahl ibn Bishr (a.k.a. Zael), whose texts were directly influential upon later European astrologers such as Guido Bonatti in the 13th century, and William Lilly in the 17th century. Knowledge of Arabic texts started to become imported into Europe during the Latin translations of the 12th century, the effect of which was to help initiate the European Renaissance.

Amongst the important names of Arabic astrologers, one of the most influential was Albumasur, whose work Introductorium in Astronomiam later became a popular treatise in medieval Europe. Another was Al Khwarizmi, the Persian mathematician, astronomer, astrologer and geographer, who is considered to be the father of algebra and the algorithm. The Arabs greatly increased the knowledge of astronomy, and many of the star names that are commonly known today, such as Aldebaran, Altair, Betelgeuse, Rigel and Vega retain the legacy of their language. They also developed the list of Hellenistic lots to the extent that they became historically known as Arabic parts, for which reason it is often wrongly claimed that the Arabic astrologers invented their use, whereas they are clearly known to have been an important feature of Hellenistic astrology.

During the advance of Islamic science some of the practices of astrology were refuted on theological grounds by astronomers such as Al-Farabi (Alpharabius), Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen) and Avicenna. Their criticisms argued that the methods of astrologers were conjectural rather than empirical, and conflicted with orthodox religious views of Islamic scholars through the suggestion that the Will of God can be precisely known and predicted in advance. Such refutations mainly concerned 'judicial branches' (such as horary astrology), rather than the more 'natural branches' such as medical and meteorological astrology, these being seen as part of the natural sciences of the time.

For example, Avicenna’s 'Refutation against astrology' Resāla fī ebṭāl aḥkām al-nojūm, argues against the practice of astrology while supporting the principle of planets acting as the agents of divine causation which express God's absolute power over creation. Avicenna considered that the movement of the planets influenced life on earth in a deterministic way, but argued against the capability of determining the exact influence of the stars. In essence, Avicenna did not refute the essential dogma of astrology, but denied our ability to understand it to the extent that precise and fatalistic predictions could be made from it.

Medieval and Renaissance Europe

Astrology became embodied in the Kabbalistic lore of Jews and Christians, and came to be the substance of the astrology of the Middle Ages. In time this would lead to Church prelates and Protestant princes using the services of astrologers. This system was referred to as "judicial astrology", and its practitioners believed that the position of heavenly bodies influenced the affairs of mankind. It was placed on a similar footing of equality and esteem with "natural astrology", the latter name for the study of the motions and phenomena of the heavenly bodies and their effect on the weather.

During the Middle Ages astrologers were called mathematici. Historically the term mathematicus was used to denote a person proficient in astrology, astronomy, and mathematics. Inasmuch as some practice of medicine was based to some extent on astrology, physicians learned some mathematics and astrology.

In the 13th century, Johannes de Sacrobosco (c. 1195–1256) and Guido Bonatti from Forlì (Italy) were the most famous astronomers and astrologers in Great Britain (the first) and in Europe (the second): the book Liber Astronomicus by Bonatti was reputed "the most important astrological work produced in Latin in the 13th century" (Lynn Thorndike).

Jerome Cardan (1501–76) hated Martin Luther, and so changed his birthday in order to give him an unfavorable horoscope. In Cardan's times, as in those of Augustus, it was a common practice for men to conceal the day and hour of their birth, till, like Augustus, they found a complaisant astrologer.

During the Renaissance, a form of "scientific astrology" evolved in which court astrologers would compliment their use of horoscopes with genuine discoveries about the nature of the universe. Many individuals now credited with having overturned the old astrological order, such as Galileo Galilei, Tycho Brahe and Johannes Kepler, were themselves practicing astrologers.

Medieval and Renaissance astrologers practiced chiromancy (also known as palmistry), which included telling fortunes by reading faces and appearances. Essentially, guessing factors in their birth chart before they would draw up the natal horoscope.

As physiognomists (see physiognomy) their talent was undoubted, and according to Lucilio Vanini there was no need to mount to the house-top to cast a nativity. "Yes," he says, "I can read his face; by his hair and his forehead it is easy to guess that the sun at his birth was in the sign of Libra and near Venus. Nay, his complexion shows that Venus touches Libra. By the rules of astrology he could not lie."

India

Main articles: Indian astronomy and Hindu astrologyThe earliest use of the term jyotiṣa is in the sense of a Vedanga, an auxiliary discipline of Vedic religion. The only work of this class to have survived is the Vedanga Jyotisha, which contains rules for tracking the motions of the sun and the moon in the context of a five-year intercalation cycle. The date of this work is uncertain, as its late style of language and composition, consistent with the last centuries BCE, albeit pre-Mauryan, conflicts with some internal evidence of a much earlier date in the second millennium BCE.

The documented history of Jyotish in the subsequent newer sense of modern horoscopic astrology is associated with the interaction of Indian and Hellenistic cultures in the Indo-Greek period. Greek became a lingua franca of the Indus valley region following the military conquests of Alexander the Great and the Bactrian Greeks. The oldest surviving treatises, such as the Yavanajataka or the Brihat-Samhita, date to the early centuries CE. The oldest astrological treatise in Sanskrit is the Yavanajataka ("Sayings of the Greeks"), a versification by Sphujidhvaja in 269/270 CE of a now lost translation of a Greek treatise by Yavanesvara during the 2nd century CE under the patronage of the Western Satrap Saka king Rudradaman I.

Indian astronomy and astrology developed together. The first named authors writing treatises on astronomy are from the 5th century CE, the date when the classical period of Indian astronomy can be said to begin. Besides the theories of Aryabhata in the Aryabhatiya and the lost Arya-siddhānta, there is the Pancha-Siddhāntika of Varahamihira.

China and East Asia

The tradition usually called 'Chinese Astrology', by Westerners is in fact not only used by the Chinese, but has a long history in other East Asian countries such as Japan, Thailand and Vietnam.

Chinese astrology

Main article: Chinese astrology

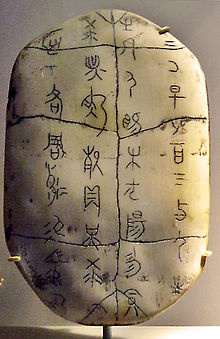

Astrology is believed to have originated in China about the 3rd millennium BC. Astrology was always traditionally regarded very highly in China, and indeed Confucius is said to have treated astrology with respect saying: "Heaven sends down its good or evil symbols and wise men act accordingly". The 60 year cycle combining the five elements with the twelve animal signs of the zodiac has been documented in China since at least the time of the Shang (Shing or Yin) dynasty (ca 1766 BC – ca 1050 BC). Oracles bones have been found dating from that period with the date according to the 60 year cycle inscribed on them, along with the name of the diviner and the topic being divined about. One of the most famous astrologers in China was Tsou Yen who lived in around 300 BC, and who wrote: "When some new dynasty is going to arise, heaven exhibits auspicious signs for the people". Astrology in China also became combined with the Chinese form of geomancy known as Feng shui .

Mesoamerica

The calendars of Pre-Columbian Mesoamerica are based upon a system which had been in common use throughout the region, dating back to at least the 6th century BCE. The earliest calendars were employed by peoples such as the Zapotecs and Olmecs, and later by such peoples as the Maya, Mixtec and Aztecs. Although the Mesoamerican calendar did not originate with the Maya, their subsequent extensions and refinements to it were the most sophisticated. Along with those of the Aztecs, the Maya calendars are the best-documented and most completely understood.

Mayan calendar

Main article: Maya calendarThe distinctive Mayan calendar and Mayan astrology have been in use in Meso-America from at least the 6th century BCE. There were two main calendars, one plotting the solar year of 360 days, which governed the planting of crops and other domestic matters; the other called the Tzolkin of 260 days, which governed ritual use. Each was linked to an elaborate astrological system to cover every facet of life. On the fifth day after the birth of a boy, the Mayan astrologer-priests would cast his horoscope to see what his profession was to be: soldier, priest, civil servant or sacrificial victim. A 584 day Venus cycle was also maintained, which tracked the appearance and conjunctions of Venus. Venus was seen as a generally inauspicious and baleful influence, and Mayan rulers often planned the beginning of warfare to coincide with when Venus rose. There is evidence that the Maya also tracked the movements of Mercury, Mars and Jupiter, and possessed a zodiac of some kind. The Mayan name for the constellation Scorpio was also 'scorpion', while the name of the constellation Gemini was 'peccary'. There is evidence for other constellations being named after various beasts, but it remains unclear. The most famous Mayan astrological observatory still intact is the Caracol observatory in the ancient Mayan city of Chichen Itza in modern day Mexico.

Aztecs

Main article: Aztec calendarThe Aztec calendar shares the same basic structure as the Mayan calendar, with two main cycles of 360 days and 260 days. The 260 day calendar was called Tonalpohualli by the Aztecs, and was used primarily for divinatory purposes. Like the Mayan calendar, these two cycles formed a 52 year 'century', sometimes called the Calendar Round .

20th century

| This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (July 2011) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

United States

In the United States, a surge of interest in astrology took place between 1900 through 1949. A popular astrologer based in New York City named Evangeline Adams helped feed the public's thirst for astrology readings. A court case involving Adams, who was arrested and charged with illegal fortune-telling in 1914 – was later dismissed when Adams correctly read the horoscope of the judge's son with only a birthdate. Her acquittal set an American precedent that if astrologers practiced in a professional manner they were not guilty of any wrong-doing.

The hunger for astrology in the earliest years of the 20th century by such astrologers as Alan Leo, Sepharial (also known as Walter Gorn Old), "Paul Cheisnard" and Charles Carter, among others, further led the surge of interest in astrology by wide distribution of astrological journals, text, papers, and textbooks of astrology throughout the United States.

In the period between 1920 and 1940 the popular media fed the public interest in astrology. Publishers realized that millions of readers were interested in astrological forecasts and the interest grew ever more intense with the advent of America's entry into the First World War. The war heightened interest in astrology. Journalists began to write articles based on character descriptions and astrological "forecasts" were published in newspapers based on the one and only factor known to the public: the month and day of birth, as taken from the position of the Sun when a person is born. The result of this practice led to modern-day publishing of Sun-Sign astrology columns and expanded to some astrological books and magazines in later decades of the 20th century.

In his 2006 book, Cosmos and Psyche: Intimations of a New World View, cultural historian Richard Tarnas presented evidence that planetary alignments meaningfully coincide with major events in human history. He also argues that a world view such as archetypal astrology in which the cosmos is intimately connected to the human psyche may provide a potential approach to resolving what he views as a global spiritual-ecological crisis.

Noted predictions

See also: Mundane astrology, Horary astrology, and Electional astrologyA favourite topic of astrologers is the end of the world. As early as 1186 the Earth had escaped one threatened cataclysm of the astrologers. This did not prevent Stöffler from predicting a universal deluge for the year 1524 – a year, as it turned out, distinguished for drought. His aspect of the heavens told him that in that year three planets would meet in the aqueous sign of Pisces. President Aurial, at Toulouse, built himself a Noah's ark – a curious realization, in fact, of Chaucer's merry invention in the Miller's Tale.

The most famous predictions about European and world affairs were made by the French astrologer Nostradamus (1503–66). Nostradamus became famous after the publication in 1555 of his work Centuries, which was a series of prophecies in cryptic verse. So obscure are the predictions that they have been interpreted as relating to a great variety of events since, including the French and English Revolutions, and the Second World War. In 1556 Nostradamus was summoned to the French court by Catherine de' Medici and commissioned to draw up the horoscope of the royal children. Although Nostradamus later fell out of favour with many in the court and was accused of witchcraft, Catherine continued to support him and patronized him until his death.

Historical figures

Throughout history astrologers have made their mark, including such figures as Ptolemy, Albumasur, Tsou Yen and Nostradamus.

Proponents

The influence of the Medici made astrologers popular in France.

Richelieu, on whose council was Jacques Gaffarel (1601–81), a noted astrologer and Kabbalist, did not despise astrology as an engine of government.

At the birth of Louis XIV a certain Morin de Villefranche was placed behind a curtain to cast the nativity of the future autocrat. A generation back the astrologer would not have been hidden behind a curtain, but would have taken precedence over the doctor. La Bruyère did not dispute this, "for there are perplexing facts affirmed by grave men who were eye-witnesses."

In England William Lilly and Robert Fludd were influential. The latter gives elaborate rules for the detection of a thief, and tells us that he has had personal experience of their efficacy. "If the lord of the sixth house is found in the second house, or in company with the lord of the second house, the thief is one of the family. If Mercury is in the sign of the Scorpion he will be bald, &c."

Francis Bacon abuses the astrologers of his day no less than the alchemists, but he does so because he envisions a reformed astrology and a reformed alchemy.

Sir Thomas Browne, while he denied the capacity of the astrologers of his day, did not dispute the reality of the science. The idea of the souls of men passing at death to the stars, the blessedness of their particular sphere being assigned them according to their deserts (the metempsychosis of J. Reynaud), may be regarded as a survival of religious astrology, which, even as late as Descartes's day, assigned to the angels the task of moving the planets and the stars.

Joseph de Maistre believed in comets as messengers of divine justice, and in animated planets, and declared that divination by astrology is not an absolutely chimerical science.

Kepler was cautious in his opinion; he spoke of astronomy as the wise mother, and astrology as the foolish daughter, but he added that the existence of the daughter was necessary to the life of the mother. He may have meant by this that the "foolish" work of astrology paid for the serious work of astronomy — as, at the time, the main motivation to fund advancements in astronomy was the desire for better, more accurate astrological predictions.

Opponents

Some distinguished men who ran counter to their age in denying stellar influences are Panaetius, Augustine, Martianus Capella (the precursor of Copernicus), Cicero, Favorinus, Sextus Empiricus, Juvenal, and in a later age Savonarola and Pico della Mirandola, and La Fontaine, a contemporary of the neutral La Bruyère.

In the Hellenistic and Roman Empire eras, a number of philosophers and scientists, such as Diogenes of Babylon (Middle Stoic), Galen, and Pliny accepted some aspects of astrology while rejecting others.

Cultural influence

Main article: Cultural influence of astrologyTo astrological politics we owe the theory of heaven-sent rulers, instruments in the hands of Providence, and saviours of society.

Napoleon, as well as Wallenstein, believed in his star. Many passages in the older English poets are unintelligible without some knowledge of astrology.

Chaucer wrote a treatise on the astrolabe; Milton refers to planetary influences; in Shakespeare's King Lear, Gloucester and Edmund represent respectively the old and the new faith.

We still contemplate and consider; we still speak of men as jovial, saturnine or mercurial; we still talk of the ascendancy of genius, or a disastrous defeat.

In French heur, malheur, heureux, malheureux, are all derived from the Latin augurium; the expression né sous une mauvaise étoile, born under an evil star, corresponds (with the change of étoile into astre) to the word malôtru, in Provençal malastrue; and son étoile palit, his star grows pale, belongs to the same class of allusions.

The Latin ex augurio appears in the Italian sciagura, sciagurato, softened into sciaura, sciaurato, wretchedness, wretched.

The influence of a particular planet has left traces in languages; but the French and English jovial and the English saturnine correspond to the gods who served as types in chiromancy rather than to the planets which bear the same names.

In the case of the expressions bien or mal luné, well or ill mooned, avoir un quartier de lune dans la tetê, to have the quarter of the Moon in one's head, the German mondsüchtig and the English moonstruck or lunatic, the fundamental idea lies in the strange opinions formerly (and in some cases, still) held about the Moon.

See also

- Astrology software

- Classical planets in Western alchemy

- International Astrology Day

- Jewish views on astrology

Footnotes

| Constructs such as ibid., loc. cit. and idem are discouraged by Misplaced Pages's style guide for footnotes, as they are easily broken. Please improve this article by replacing them with named references (quick guide), or an abbreviated title. (November 2011) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

- Campion (2008) pp.2-3.

- Marshack (1972) p.81ff.

- Hesiod (c. 8th cent. BCE). Hesiod’s poem Works and Days demonstrates how the heliacal rising and setting of constellations were used as a calendical guide to agricultural events, from which were drawn mundane astrological predictions, e.g.: “Fifty days after the solstice, when the season of wearisome heat is come to an end, is the right time to go sailing. Then you will not wreck your ship, nor will the sea destroy the sailors, unless Poseidon the Earth-Shaker be set upon it, or Zeus, the king of the deathless gods” (II. 663-677).

- Kelley and Milone (2005) p.268.

- Two texts which refer to the 'omens of Sargon' are reported in E. F. Weidner, ‘Historiches Material in der Babyonischen Omina-Literatur’ Altorientalische Studien, ed. Bruno Meissner, (Leipzig, 1928-9), v. 231 and 236.

- From scroll A of the ruler Gudea of Lagash, I 17 – VI 13. O. Kaiser, Texte aus der Umwelt des Alten Testaments, Bd. 2, 1-3. Gütersloh, 1986-1991. Also quoted in A. Falkenstein, ‘Wahrsagung in der sumerischen Überlieferung’, La divination en Mésopotamie ancienne et dans les régions voisines. Paris, 1966.

- Michael Baigent (1994). From the Omens of Babylon: Astrology and Ancient Mesopotamia. Arkana.

- Michael Baigent, Nicholas Campion and Charles Harvey (1984). Mundane astrology. Thorsons.

- Steven Vanden Broecke (2003). The limits of influence: Pico, Louvain, and the crisis of Renaissance astrology. BRILL. pp. 185–. ISBN 978-90-04-13169-9. Retrieved April 5, 2012.

- Hugh Thurston. Early Astronomy, (New York: Springer-Verlag, 1994), p. 135-137

- Scientifically Dating the Constellations

- Brown, David, 2000. Mesopotamian Planetary Astronomy-Astrology; p.107. Cuneiform Monographs 18. Groningen: Styx Publications, 2000. ISBN 90-5693-036-2.

- Koch-Westenholz, Ulla, 1995. Mesopotamian astrology; p.100. The reference to Sebettu is interpreted as an eclipse myth. Volume 19 of CNI publications. Museum Tusculanum Press, 1995. ISBN 978-87-7289-287-0.

- Brown, David, Mesopotamian planetary astronomy-astrology, pp.63-72. Cuneiform Monographs 18. Groningen: Styx Publications, 2000. ISBN 90-5693-036-2.

- Derek and Julia Parker, Ibid, p16, 1990

- Yamamoto 2007. sfn error: no target: CITEREFYamamoto2007 (help)

- Houlding (2010) Ch. 8: 'The medieval development of Hellenistic principles concerning aspectual applications and orbs'; pp.12-13.

- Albiruni, Chronology (11th c.) Ch.VIII, ‘On the days of the Greek calendar’, re. 23 Tammûz; Sachau.

- Houlding (2010) Ch. 6: 'Historical sources and traditional approaches'; pp.2-7.

- Saliba (1994) p.60, pp.67-69.

- Belo (2007) p.228.

- George Saliba, Avicenna: 'viii. Mathematics and Physical Sciences'. Encyclopaedia Iranica, Online Edition, 2011, available at http://www.iranica.com/articles/avicenna-viii

- Article on astrology from the Catholic Encyclopaedia, 1907 edition

- http://www.stanford.edu/dept/HPS/colloquia0405.html Galileo, Astrology and the Scientific Revolution: Another Look

- "Stemmed search for mathematicus", Ultralingua Online Dictionary, Ultralingua, retrieved March 23, 2007

- http://members.aol.com/jeff570/m.html Earliest Known Uses of Some of the Words of Mathematics

- Sastry, T.S.K. K.V. Sarma (ed.). "Vedanga jyotisa of Lagadha" (PDF). National Commission for the Compilation of History of Sciences in India by Indian National Science Academy, 1985. Retrieved November 22, 2009.

- Pingree, David (1981), Jyotiḥśāstra, Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz p.9

- Pingree (1981), p.81

- Mc Evilley "The shape of ancient thought", p385 ("The Yavanajataka is the earliest surviving Sanskrit text in horoscopy, and constitute the basis of all later Indian developments in horoscopy", himself quoting David Pingree "The Yavanajataka of Sphujidhvaja" p5)

- Derek and Julia Parker, Ibid 1991

- Parker and Parker Ibid, 1971

- Michael D. Coe, 'The Maya', pp. 227–29, Thames and Hudson, London, 2005

- Daniel Pinchbeck, "Psyching Out The Cosmos" Reality Sandwich

- Derek and Julia Parker, Ibid, p201, 1990

Sources

- Al Biruni (11th c.), The Chronology of Ancient Nations; tr. C. E. Sachau. London: W.H Allen & Co, 1879. Online edition available on the Internet Archive, retrieved 6 August 2011.

- Belo, Catarina, 2007. Chance and determinism in Avicenna and Averroës. London: Brill. ISBN 90-04-15587-2.

- Campion, Nicholas, 2008. A History of Western Astrology, Vol. 1, The Ancient World (first published as The Dawn of Astrology: a Cultural History of Western Astrology. London: Continuum. ISBN 978-1-4411-8129-9.

- Hesiod (c. 8th cent. BCE) . Hesiod, the Homeric Hymns, and Homerica translated by Evelyn-White, Hugh G., 1914. Loeb classical library; revised edition. Cambridge: Harvard Press, 1964. ISBN 978-0-674-99063-0.

- Kelley, David, H. and Milone, E.F., 2005. Exploring ancient skies: an encyclopedic survey of archaeoastronomy. Heidelberg / New York: Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-95310-6.

- Houlding, Deborah, 2010. Essays on the history of western astrology. Nottingham: STA. ISBN 1-899503-55-9 .

- Marshack, Alexander, 1972. The roots of civilization: the cognitive beginnings of man's first art, symbol and notation. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-1-55921-041-6.

- Saliba, George, 1994. A History of Arabic astronomy: planetary theories during the Golden Age of Islam. New York University Press. ISBN 0-8147-7962-X.

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty |title= (help)

Further reading

- T. Barton, Ancient Astrology. Routledge, 1994. ISBN 0-415-11029-7.

- B. Bobrick, The Fated Sky: Astrology in History. Simon & Schuster, 2006. ISBN 0-7432-6895-4.

- Nicholas Campion, A History of Western Astrology Vol. 2, The Medieval and Modern Worlds, Continuum 2009. ISBN 978-1-84725-224-1.

- Nicholas Campion, The Great Year: Astrology, Millenarianism, and History in the Western Tradition. Penguin, 1995. ISBN 0-14-019296-4.

- A. Geneva, Astrology and The Seventeenth Century Mind: William Lilly and the Language of the Stars. Manchester Univ. Press, 1995. ISBN 0-7190-4154-6.

- James Herschel Holden, A History of Horoscopic Astrology. (Tempe, Az.: A.F.A., Inc., 2006. 2nd ed.) ISBN 0-86690-463-8.

- M. Hoskin, The Cambridge Concise History of Astronomy. Cambridge Univ. Press, 2003. ISBN 0-521-57600-8.

- L. MacNeice, Astrology. Doubleday, 1964. ISBN 0-385-05245-6

- W. R. Newman, et al., Secrets of Nature: Astrology and Alchemy in Early Modern Europe. MIT Press, 2006. ISBN 0-262-64062-7.

- G. Oestmann, et al., Horoscopes and Public Spheres: Essays on the History of Astrology. Walter de Gruyter Pub., 2005. ISBN 3-11-018545-8.

- F. Rochberg, The Heavenly Writing: Divination, Horoscopy, and Astronomy in Mesopotamian Culture. Cambridge Univ. Press, 2004. ISBN 0-521-83010-9.

- J. Tester, A History of Western Astrology. Ballantine Books, 1989. ISBN 0-345-35870-8.

- T. O. Wedel, Astrology in the Middle Ages. Dover Pub., 2005. ISBN 0-486-43642-X.

- P. Whitfield, Astrology: A History. British Library, 2004. ISBN 0-7123-4839-5.

External links

- Hellenistic Astrology – An Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry outlining the development of Hellenistic astrology and its interaction with philosophical schools.

- History of Astrology The history of astrology and major astrologers through the ages.

- Marriage and Divorce of Astronomy and Astrology: History of Astral Prediction from Antiquity to Newton and Beyond by Gordon Fisher

- Bibliography of Mesopotamian Astronomy and Astrology

- Comprehensive survey of the history of astrology

- Survey of History of Astrology An in-depth survey of astrological history, by Julia & Derek Parker.