This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Cvene64 (talk | contribs) at 04:04, 30 April 2006 (→Reception: domestic/ww figures). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 04:04, 30 April 2006 by Cvene64 (talk | contribs) (→Reception: domestic/ww figures)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) 2006 film| V for Vendetta | |

|---|---|

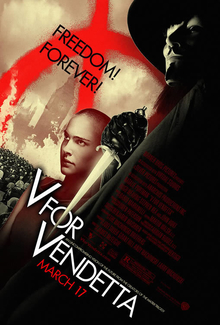

V for Vendetta theatrical poster V for Vendetta theatrical poster | |

| Directed by | James McTeigue |

| Written by | The Wachowski brothers (screenplay) |

| Produced by | Joel Silver The Wachowski brothers |

| Starring | Natalie Portman Hugo Weaving Stephen Rea John Hurt and Stephen Fry |

| Music by | Dario Marianelli |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. |

| Release dates | March 17, 2006 |

| Running time | 132 mins. |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $54 million (US) |

V for Vendetta is a 2006 film set in London's near-future, and follows V, a freedom fighter, who uses terrorist tactics in pursuit of both a personal vendetta and sociopolitical change in a dystopian Britain. The film was directed by James McTeigue and produced by Joel Silver and the Wachowski brothers, who also wrote the screenplay. The film stars Natalie Portman as Evey Hammond, Hugo Weaving as V as well as Stephen Rea as Inspector Finch and John Hurt as Chancellor Sutler. After the release date of November 5, 2005 was delayed, the film opened in conventional as well as IMAX theatres on March 17, 2006, and has been generally well received.

The film is an adaptation of the graphic novel V for Vendetta by Alan Moore and David Lloyd. Due to ongoing conflicts with the film industry, Moore did not endorse the film. The film tones down the anarchist themes that were present in the original story and revised the story to better reflect current issues. Due to the politically sensitive content of the film, V for Vendetta has been the target of both criticism and praise from various groups.

Plot

The story is set in the near future, where Britain is ruled by a totalitarian regime called Norsefire. It follows the tale of Evey Hammond, a young woman who at the start of the film is rescued from state police by a masked vigilante known as "V". After rescuing her, V shows her his spectacular destruction of the Old Bailey. The regime explains the incident to the public as a planned demolition. But this is proved a lie when V takes over the state-run news station the next day. He broadcasts a message urging all of Britain to rise up with him against the oppressive government on November 5, one year from that day, when V will destroy Parliament. Evey, who coincidentally works at the station, ends up helping V escape and V brings Evey to his lair. She is told that she must stay in hiding with him for her safety. She stays for some time, but upon learning that V is killing government officials, she escapes to the the home of one of her superiors. Unfortunately, the state police raid the home shortly after, and Evey is captured. She is incarcerated and tortured for days, finding solace only in notes left by another prisoner, Valerie. Evey is eventually threatened with execution unless she tells them V's whereabouts. An exhausted Evey says she would rather die, and surprisingly is then released. Evey finds that she has been in V's lair all along, and that the event was staged by V in order to make her experience what he went through long ago, and to understand that an idea can be more important than a life without ideas. Evey initially hates V for it, but she eventually understands. She leaves V, promising to return before November 5.

Meanwhile, Chief Inspector Finch, through his investigation of V, eventually learns how the regime came to power and about the origins of V. Years ago, an outbreak of a disease killed nearly 100,000 people in England. Miraculously, a group of ultra-conservatives (Norsefire) devised a cure and were heralded as the nation's saviours. This group was elected into office in a landslide, and quickly turned it into the totalitarian state it is in the film. However, the disease itself was actually created by the group as part of a ploy to gain power. The disease was engineered through experimentation on "social deviants" and political dissidents at Larkhill prison. V was one of the prisoners, but instead of dying, he gained heightened mental and physical abilities from the treatments. V eventually escaped, destroyed the prison, and vowed to have his revenge upon the regime for the crimes they've committed.

As November 5 nears, V's various schemes cause chaos in Britain, as the population grows more and more subversive to government authority. On the eve of November 5, V is visited again by Evey, whom he shows a train he has filled with explosives in order to destroy Parliament through the abandoned London underground. He defers the final act to destroy Parliament to Evey, his "gift" to her, due to his belief that the ultimate decision should not come from him. He then leaves to meet Party leader Creedy, who as part of an earlier agreement has agreed to bring V the Chancellor in exchange for V's surrender. Creedy kills the Chancellor in front of V, but unfortunately for Creedy, V does not surrender and instead kills Creedy and his men. V is mortally wounded in the process and returns to Evey. He thanks her, dies, and is then placed onto the train with the explosives. Evey is about to release the train when she is found by Inspector Finch. But because of his new knowledge about the regime, Finch allows Evey to proceed. During this time, almost every citizen in London has marched to Parliament to watch the event, wearing Guy Fawkes masks that were sent by V. (The military who was originally ordered to stop them, stands down.) Soon, Parliament is destroyed in a dazzling spectacle set to the 1812 Overture. On a nearby rooftop Evey and Finch watch the scene together and hope for a better tomorrow. Template:Endspoilers

Development

Producer Joel Silver acquired the rights to two of Alan Moore's texts, V for Vendetta and Watchmen in 1988. Although Watchmen changed hands over the years, Silver did hold on to V for Vendetta. The Wachowski brothers were fans of the original graphic novel and in the mid-1990's, before working on The Matrix, wrote a draft screenplay that followed very closely the graphic novel. During the post production of the last two Matrix films, the Wachowski brothers revisited the script and offered James McTeigue a director's role. All three were intrigued by the themes of the novel and viewed them particularly relevant to the current political climate at the time. Upon revisiting the script again, the Brothers set about making revisions to condense, modernize and move the story into the future. At the same time, they attempted to preserve the integrity and themes of the original work.

Moore explicitly disassociated himself from the film adaptation, continuing an ongoing dispute over film adaptations of his work. He ended cooperation with his publisher, DC Comics, after its corporate parent, Warner Bros., failed to retract statements about Moore's supposed endorsement of the film. Moore said that the script contained plot holes and that it ran contrary to the entire theme of his original work, which was to place two political extremes (fascism and anarchism) against one another, while allowing readers to decide for themselves whether V's actions were right or insane. He argues his story had been recast as "current American neo-conservatism vs. current American liberalism". As per his wishes, Moore's name does not appear in the film's closing credits. Meanwhile, co-creator and illustrator David Lloyd supports the film adaptation, commenting that the script is very good and that Moore would only ever be truly happy with a complete book to screen adaptation.

Production

V for Vendetta was filmed in London, UK and in Potsdam, Germany at Babelsberg Studios. A large amount of the film was shot on sound-stages and indoor sets, with location work done in Berlin for three scenes: the Norsefire rally flashback, Larkhill and Bishop Lilliman’s bedroom. The scenes taking place in the abandoned London Underground were filmed at the disused Aldwych tube station. Filming began in early March 2005 and principal photography officially wrapped in early June of 2005.

The film was set to have a future-retro look to it, with a predominant use of grey-tones to give a dreary stagnant look to the totalitarian nation. The largest set created for the film was the Shadow Gallery, which was made to feel like a mix between a crypt and an undercroft. The Gallery is V's home as well as a place where he stores various artifacts deemed forbidden by the government. Some of the works of art displayed in the gallery include The Arnolfini Portrait by Jan Van Eyck, Bacchus and Ariadne by Titian, a Mildred Pierce poster and The Lady of Shalott by John William Waterhouse.

To film the final scene at Westminster, the area from Trafalgar Square and Whitehall up to Parliament and Big Ben had to be closed for three nights from 12 - 5 a.m. This was the first time the security-sensitive area (home to 10 Downing Street and the Ministry of Defense) had ever been closed to accomodate filming. Prime Minister Tony Blair's son Euan Blair worked on the film's production and is said (through an interview with Stephen Fry) to have helped the filmmakers obtain the unparalleled filming access. This drew criticism for Blair from MP David Davis due to the content of the film. However, the makers of the film deny Euan Blair's involvement in the deal, stating that access was acquired through nine months of negotiations with 14 different government departments and agencies.

V for Vendetta is also the final film shot by noted cinematographer Adrian Biddle, who died of a heart attack on December 7, 2005.

Cast

- Natalie Portman as Evey Hammond: Director James McTeigue first met Portman on the set of Attack of the Clones, where he worked with her as assistant director. Natalie received top billing for the film. In preparing for the role, Portman worked with a dialectologist in order to perform a successful English accent. She also studied films like The Weather Underground and read the autobiography of Menachem Begin. She is the only American cast member in the film.

- Hugo Weaving as V: James Purefoy was originally cast as V but left six weeks into filming due to difficulties wearing the mask for the entire film. He was replaced by Hugo Weaving, who previously worked with Joel Silver and the Wachowski brothers on The Matrix trilogy as Agent Smith.

- Stephen Rea as Eric Finch: In the film, Inspector Finch's Irish background cause his loyalties to be questioned by Creedy. Actor Stephen Rea is also Irish and, interestingly, was once married to Dolours Price, a former member of the Provisional Irish Republican Army, imprisoned for bombing the Old Bailey.

- John Hurt as Adam Sutler: Playing Chancellor Sutler was complete role reversal for John, as he played the part of Winston Smith, a victim of the state in the film adaptation of Nineteen Eighty-Four.

- Stephen Fry as Gordon Dietrich: Talk-show host Gordon Dietrich is a closeted homosexual who, due to the restrictions of the regime, has "lost his appetite" over the years. This has some parallels with Stephen Fry, who is also homosexual and has famously practiced a celibate lifestyle for over 16 years. Though, when asked in an interview what he liked about the role, Stephen replied "Being beaten up! I hadn't been beaten up in a movie before and I was very excited by the idea of being clubbed to death."

- Sinead Cusack as Dr. Delia Surridge: Dr. Surridge was the head physician at the Larkhill detention center.

- John Standing as Bishop Lilliman: In regards to his role as Lilliman, Standing remarks, "I thoroughly enjoyed playing Lilliman... because he's slightly comic and utterly atrocious. Lovely to do."

- Tim Pigott-Smith as Creedy: Creedy is Norsefire's party leader as well as the Head of Britain's Secret police, the Finger. While Sutler may be Chancellor, the real power lies with Creedy.

- Rupert Graves as Dominic: Dominic is Inspector Finch’s lieutenant in the V investigation.

- Natasha Wightman as Valerie: Valerie's symbolic role as a victim of the state was received positively by many LGBT critics. Film critic Michael Jensen praised the extraordinarily powerful moment of Valerie's scene "not just because it is beautifully acted and well-written, but because it is so utterly unexpected" (in a Hollywood film).

- Roger Allam as Lewis Prothero: Lewis Prothero or the "The Voice of London" has been commonly viewed as a parody of Bill O'Reilly by critics and commentators.

- Ben Miles as Dascombe: Though never explicitly mentioned in the film, Dascombe is Sutler's head of propaganda.

- Clive Ashborn as Guy Fawkes: The story of Guy Fawkes is described in the beginning of the film, and serves as the historical inspiration for V.

Publicity and release

On 15 June members of the cast and crew did their first major press conference at Comic-Con in San Diego. July saw the first poster for the film distributed to theatres and the first trailer became available on the film's official website. (Interestingly, the official website can also be accessed through the URL 'whowatchesthewatchmen.com', as it was once the official site of the Watchmen film adaptation.)

The film was originally scheduled to be released on the weekend of November 5, 2005 with the tagline "Remember, remember the 5th of November", the first line of a traditional British rhyme recounting the discovery of the Gunpowder Plot to blow up Parliament in 1605. The 5th of November 2005 was the 400th anniversary of the infamous plan. The Gunpowder Plot imagery is leant on extensively by both the graphic novel and the film, with V behaving as a latter-day Guy Fawkes (albeit more successful) in his destruction of the Houses of Parliament, an event which, in the original graphic novel, took place on that same anniversary in 1997 with V reciting the rhyme and dressed as Guy Fawkes. However, the creative marketing angle lost much of its value when in late 2005, the release date was pushed back to March 17, 2006. Some have speculated this was due to the London bombings on 7 July and 21 July. The film-makers have denied this, and say it was delayed to allow more time for production, explaining that the visual effects would not be completed in time.

On November 15, a special internet campaign was launched following the delay of the film. Four new film posters (sporting propaganda-like artwork) were distributed to four independent websites. On December 15, a new trailer became available online. In addition, Warner Bros. promoted three of its biggest films of 2006, Poseidon, 16 Blocks and V for Vendetta, during the broadcast of Super Bowl XL.

V for Vendetta had its major world premier on February 14 at the Berlin Film Festival. It opened for general release on March 17, 2006 in 3,365 theatres in the United States as well as the United Kingdom and six other countries. Major theatres decorated the exterior of their buildings with Norsefire flags.

Music

Main article: V for Vendetta (soundtrack)The V for Vendetta soundtrack was released by Astralwerks Records on March 21, 2006. The original scores from the film's composer, Dario Marianelli, make up most of the tracks on album. The soundtrack also features 3 of the vocals played in the film, which include: Cry Me A River by Julie London, I Found A Reason by Cat Power and Bird Gerhl by Antony and the Johnsons. These songs were a sample of the 872 blacklisted tracks on V's Wurlitzer jukebox that he reclaimed from the Ministry of objectionable materials. The climax of Tchaikovsky's 1812 Overture appears at the track Knives and Bullets (and Cannons too). The revolutionary sounding Overture is played at key parts at the beginning and end of the film.

Three songs were played in the ending credits which were not included on the V for Vendetta soundtrack. The first was "Street Fighting Man" by the Rolling Stones. The second song was special version of Ethan Stoller's BKAB. In keeping with revolutionary tone of the film, the song contains excerpts from "On Black Power" by black nationalist leader Malcolm X, as well as from "Address to the Women of America" by feminist-writer Gloria Steinem. Gloria Steinem can be heard saying: "This is no simple reform... It really is a revolution. Sex and race, because they are easy and visible differences, have been the primary ways of organizing human beings into superior and inferior groups and into the cheap labor in which this system still depends." The final song was "Out of Sight" from Spiritualized. Also in the film were the Antonio Carlos Jobim songs The Girl From Ipanema and "Quiet Nights of Quiet Stars". These songs were played during the "breakfast scenes" with V and Deitrich and were one of the ways used to tie the two characters together. Beethoven's Symphony No.5 also plays an important role in the film, with the first four notes of the song signifying the letter "V" in Morse code. Gordon Dietrich's Benny Hill styled comedy sketch of Chancellor Sutler includes the Yakety Sax theme. Amusingly, Inspector Finch's alarm clock begins 5 November, with the song "Long Black Train" by Richard Hawley, with the foreshadowing lyrics "Ride the long black train... take me home black train."

Differences between the film and graphic novel

- For more information: V for Vendetta.

The story of the film V for Vendetta was taken from an Alan Moore comic originally published between 1982 and 1985 in the British comic anthology Warrior. The series was later compiled into a graphic novel and published again in the United States under DC's Vertigo imprint and in the United Kingdom under Titan Books. While the film is often seen as a faithful adaptation of the original novel, there are many key differences between the two that make them fundamentally different.

Firstly, Alan Moore's original version was created as a response to British Thatcherism in the early 80's and set as a conflict between a fascist state and anarchism. In the film, the overarching story has been changed by the Wachowskis to fit a modern political context. Alan Moore charges that in doing so, the story has turned into an American-centric conflict between liberalism and neo-conservatism, abandoning the original anarchist-fascist themes. As well, there was an emphasis by Moore to maintain moral ambiguity in the original story and not portray the fascists as caricatures, but as real rounded characters. Finally, the time limitations of the film naturally meant that it had to omit various characters, details and plotlines from the original story.

While V is characterized as a romantic freedom fighter in the film, the novel portrays V as an anarchist whose actions are questionable. He neither cooks breakfast for Evey, nor is he romantic and is instead portrayed as something bizarre. Evey Hammond undergoes a more drastic change in the novel than she does in the film. In the beginning of the film, she is already a confident woman with a hint of rebellion in her. Whereas, in the novel she starts off as an insecure, desperate young prostitute. By the end of the graphic novel, not only does she carry out V’s plans as she does in the film, but she also clearly takes on V’s mantle. As well, while Chancellor Sutler is portrayed as a 2D totalitarian figure in the film, the novel portrays him as sympathetic and troubled character.

The setting in Moore’s original story was also much darker than the relatively secure setting of the film. In the graphic novel, a global nuclear war has destroyed Continental Europe and Africa, but has spared Britain. However, Britain stands isolated, and with a nuclear winter causing famine and massive flooding, there is a real fear that a collapse of the government would lead to disaster. (This makes V’s efforts to destroy the regime even more questionable.)

Norsefire's choice of "enemies" has also changed. Whereas the ultra-conservative regime of tomorrow targets homosexuals and Muslims, the fascist regime of yesterday focused on the protection of racial purity. Racial undesirables were detained and executed, (though homosexuals and leftists were targets as well). Despite playing down racial elements, the film retains the Aryan superhero Storm Saxon.

Some of the plotlines omitted from the film include the story surrounding Ms Almond and Mr. and Mrs. Heyer. As well, the computer system "Fate" is completely missing from the film. (Fate was a Big-Brother-like computer which served as Norsefire's eyes and ears and also helped explain how V could see and hear the things he did). V's terrorist targets are different in the graphic novel, as he begins with destroying Parliament and the Old Bailey, and destroys 10 Downing Street for the finale. And finally, whereas the film ends in relative peace, in the graphic novel there is a total collapse of authority and the beginnings of anarchy.

Themes

A modern totalitarian dystopia

“We felt the novel was very prescient to how the political climate is at the moment. It really showed what can happen when society is ruled by government, rather than the government being run as a voice of the people. I don’t think it’s such a big leap to say that things like that can happen when leaders stop listening to the people.” Director James McTeigue

As a film about the struggle between freedom and the state, V for Vendetta takes imagery from many classic totalitarian icons both real and fictional, including Nazi Germany and George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four. For example, Sutler (who was actually named after Adolf Hitler) primarily appears on large video screens and on pictures hung in people's homes, reminiscent of Big Brother. In another reference to Orwell's novel, the slogan "Strenght through Unity. Unity through Faith" is displayed across London, similar to "War is peace. Freedom is Slavery. Ignorance is Strength" in Orwell's Oceania. As well, there is the state's extensive use of mass surveillance on its citizens, including closed-circuit television. (Britain currently has the world's highest concentration of CCTV.) As well, Valerie was sent to a detention facility for being a lesbian and then had medical experiments performed on her. This is similar to Nazi Germany's treatment of gays during the Holocaust. The media is portrayed as being highly subservient to government propaganda, a common criticisms about totalitarian regimes in general. Norsefire replaced St George's Cross with the Cross of Lorraine as their Nordic-style national symbol. This was the symbol used by Free French Forces in WWII, chosen because it was a traditional French patriotic symbol that could be used as an answer to the Nazi's Swastika. The colours of the Norsefire flag, red and black, are also similar to the ones used by the Nazis.

With the intention of making the film relevant to today’s audience, the filmmakers included many modern day references as well. For example, the culture of fear montage of news stories ordered by Sutler contains references to an avian flu pandemic. As well there is siginficant use of signal-intelligence gathering and analysis by the regime. Many have also noted the numerous references in the film to the current American administration. These include the "black bags" worn by the prisoners in Larkhill that have been seen as a reference to the black bags worn by prisoners at Abu Ghraib in Iraq and Guantánamo Bay in Cuba. Also London is under a yellow-coded curfew alert, which is similar to the US Government's color-coded Homeland Security Advisory System. One of the forbidden items in Gordon's secret basement is a protest poster with a mixed US–UK flag with a swastika and the title "Coalition of the Willing, To Power." This is likely a reference to the real Coalition of the Willing that was formed for the Iraq War. (At the same time, it also appears to be a reference to Friedrich Nietzsche's concept of Will to Power). As well, there is frequent use of the term "rendition" in the film. There is even a brief scene (during the Valerie flashback) containing real-life footage of a anti-Iraq war demonstration, with mention of President George W Bush.

Much of the modern US imagery can be personified in the character Lewis Prothero. As the talk show host “The Voice of London” Lewis can be seen evoking the image of conservative American pundits like Bill O'Reilly and Rush Limbaugh, (particularly with Limbaugh and Prothero's drug use). Furthermore, with his rhetoric about God, gays, and Muslims, Prothero is likely to be a caricature of religious right-wing commentators like Pat Robertson. Prothero's combat record seems to be an allusion to the current war in Iraq and other potential regions of conflict in the Middle-East ("Iraq, Kurdistan, Syria, before and after...").

While modern references do exist, they were likely included for illustrative purposes rather than specifically attacking the US administration, as the majority of the totalitarian references in the film are non-specific. When James McTeigue was asked whether or not BTN was based on Fox News McTeigue replied, "Yes. But not just Fox. Everyone is complicit in this kind of stuff. It could just as well been the Britain's Sky News Channel."

The letter V and the number 5

“Voilà! In view, a humble vaudevillian veteran, cast vicariously as both victim and villain by the vicissitudes of fate. This visage, no mere veneer of vanity, is a vestige of the vox populi, now vacant, vanished. However, this valorous visitation of a bygone vexation stands vivified, and has vowed to vanquish these venal and virulent vermin vanguarding vice and vouchsafing the violently vicious and voracious violation of volition. The only verdict is vengeance; a vendetta held as a votive, not in vain, for the value and veracity of such shall one day vindicate the vigilant and the virtuous. Verily, this vichyssoise of verbiage veers most verbose, so let me simply add that it's my very good honor to meet you and you may call me V.” — V's introduction to Evey

There is repeated reference to the letter “V”, or 5 in Roman numerals, throughout the film. V is held in Larkhill cell number “V”. V's favorite phrase is “By the power of truth, I, a living man, have conquered the universe”, (which in Latin is “Vi Veri Veniversum Vivus Vici.” Note: 5 V’s) V’s Zorro-like signature is a "V", as are his fireworks displays. During the battle with Creedy and his men, V forms a “V” with his daggers just before he throws them. After the battle, when V is mortally wounded, V leaves a “V” signature in his own blood. V’s introduction to Evey (above) begins and ends with “V”, has five sentences, and contains 49 words that begin with “V”. The Old Bailey and Parliament are destroyed on the fifth of November. V’s final song with Evey, is song number 5 on his jukebox. When V confronts Creedy, V plays Beethoven's Fifth Symphony, whose opening notes have a rhythmic pattern that resembles the letter “V” in Morse code (···–). The Symphony’s opening was used as a call-sign in the European broadcasts of the BBC during World War II in reference to Winston Churchill’s “V for Victory”. The film’s title itself, is also a reference to “V for Victory”. Finally, an inverted red-on-black “A” symbol for anarchy is shown as V’s “V” symbol.

Reception

V for Vendetta has thus far grossed (USD) $68,422,483 in the United States and $45,200,000 elsewhere, for a worldwide gross of $113,622,483. The film led the United States box office on its opening day, taking in an estimated $8,350,000 and remained the number one film for the remainder of the weekend, taking in an estimated total of $25,642,340. Its closest rival, Failure to Launch, took in $15,815,000. The film debuted at number one in South Korea, Taiwan, Sweden, Singapore and the Philippines. Despite the film taking place in Great Britain, the film did not reach number one at their box office on the opening weekend; instead, The Pink Panther took the number one spot. V for Vendetta also opened in 56 IMAX theaters in North America, grossing $1.36 million during the opening three days.

The critical reception of the film has largely been positive, with the film review collection website, Rotten Tomatoes, giving the film a 75% Fresh approval. Ebert & Roeper gave the film two thumbs up with Roger Ebert stating that V for Vendetta "almost always has something going on that is actually interesting, inviting us to decode the character and plot and apply the message where we will." Margaret Pomeranz and David Stratton from At the Movies state that despite problems with not being able to see Hugo's face, there was good acting and an interesting plot, adding that the film is also disturbing with scenes that are reminiscent of Nazi Germany. Jonathan Ross from the BBC blasted the film, calling it a "woeful, depressing failure" and stating that the "cast of notable and familiar talents such as John Hurt and Stephen Rea stand little chance amid the wreckage of the Wachowski siblings' dismal script and its particularly poor dialogue." While Harry Guerin from RTE states the film "works as a political thriller, adventure and social commentary and it deserves to be seen by audiences who would otherwise avoid any/all of the three", adding that the film will become "a cult favourite whose reputation will only be enhanced with age"

Comments from political sources

Overall the film V for Vendetta deals with issues of race, sexuality, religion, government control and terrorism. Its controversial storyline and themes have, inevitably, made it the target of both criticism and praise from various groups.

An anarchist group in New York City has used the release of the film to gain publicity for anarchism as a political philosophy. However, the group felt that the film waters down the anarchist message from the original story in order to satisfy mass Hollywood audiences, and instead focuses on destruction without proposing any alternatives. Despite the lack of acceptance by anarchists, the film has brought renewed interest to Alan Moore's original story, as sales of the original graphic novel rose dramatically in the United States, placing the book firmly in the top sales at Barnes & Noble and Amazon.com.

Many libertarians, especially at the Mises Institute's LewRockwell.com see the film as a positive depiction in favor of a free society with limited government and free enterprise, citing the state's terrorism as being of greater evil and rationalized by its political machinery, while V's acts are seen as 'terroristic' because they are done by a single individual. Justin Raimondo, the libertarian editor of AntiWar.com, praised the film for its sociopolitical self-awareness and saw the film’s success as “helping to fight the cultural rot that the War Party feeds on".

Several conservative Christian groups were critical of film's negative portrayal of Christianity and sympathetic portrayal of homosexuality and Islam. Ted Baehr, chairman of the Christian Film and Television Commission, called V for Vendetta a vile, pro-terrorist piece of neo-Marxist, left-wing propaganda filled with radical sexual politics and nasty attacks on religion and Christianity. Don Feder, a conservative columnist from Frontpage Magazine has called V for Vendetta "the most explicitly anti-Christian movie to date." Meanwhile, LGBT commentators have praised the film for its positive depiction of gays, in particular, Valerie's symbolic role in the film. As well, liberal filmmaker Michael Moore has endorsed the film.

David Walsh from the World Socialist Web Site criticizes V's actions as "antidemocratic" and cites the film as an example of "the bankruptcy of anarcho-terrorist ideology" stating that because the people have not played any part in the revolution, they will be unable to produce a "new, liberated society."

Novelization

Main article: V for Vendetta (novelization). This should not be confused with the original graphic novel.

A novelization of the screenplay was written by comic writer Steve Moore, the same writer credited to first introducing Alan Moore to comics. (The two artists are not related). The novel follows very closely to the film's screenplay, but elaborates on a few scenes by reviving details from the original story. For example, it provides details surrounding V's escape from Larkhill by describing V "storing" bags of fertilizer at various points in the building.

Notes

- ^ "V for Vendetta (2006)". boxofficemojo.com. Retrieved 24 April.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "V for Vendetta news". vforvendetta.com. Warner Brothers. Retrieved 31 March.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "Production Notes for V for Vendetta". official webpage. vforvendetta.com. Retrieved 14 april.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "MOORE SLAMS V FOR VENDETTA MOVIE, PULLS LoEG FROM DC COMICS". comicbookresources.com. Retrieved 5 June.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "A FOR ALAN, Pt. 1: The Alan Moore interview". MILE HIGH COMICS presents THE BEAT at COMICON.com. GIANT Magazine. Retrieved 21 March.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "V AT COMIC CON". vforvendetta.com. Retrieved 14 November.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) -

{{cite AV media}}: Empty citation (help) - ^ "V for Vendetta - About the production". ssfworld.com. Retrieved 22 April.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "The How E put the V in Vendetta". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 March.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "James Purefoy Quit 'V For Vendetta' Because He Hated Wearing The Mask". starpulse.com. Retrieved 7 April.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "Film Interview – Stephen Rea / 'V For Vendetta' - The Rea Thing". eventguide.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|Accessdate=ignored (|accessdate=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "Exclusive Interview with Stephen Fry - V for Vendetta". filmfocus.com. Retrieved 19 April.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "V for Vendetta: A Brave, Bold Film for Gays and Lesbians". afterellen.com. Retrieved 6 April.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "Natalie Portman's 'V For Vendetta' Postponed". sfgate.com. Retrieved 25 April.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "DC's Virtual Panopticon". theNation. Retrieved 28 April.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "V for Vendetta (2006)". decentfilms.com. Retrieved 25 April.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "Gunpowder, treason and plot". March 19, 2006.

- ^ Owen Gleiberman. "EW review: 'V for Vendetta,' O for OK". CNN. Time Warner.

- ^ David Denby (March 13, 2006). "BLOWUP: V for Vendetta". The New Yorker. Conde Nast.

- ^ Debbie Schlussel (March 13, 2006). ""V" for Vicious Propaganda". FrontPage.

- ^ "V for Vendetta". Christianitytoday.com. Retrieved April 29.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ Germain, David (Mar 16, 2006). "'V' for Victory". Monterey County Herald. Retrieved 2006-04-10.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - "V for verbose vigilante". csmonitor. March 17, 2006.

- "Failure to Launch (2006) - Daily Box Office". boxofficemojo.com. Retrieved 20 March.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "'V' for (international) victory". Boston Herald. Retrieved 22 March.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "V for Vendetta Posts Strong IMAX Opening". vfxworld.com. Retrieved 22 March.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "V for Vendetta (2006)". rottentomatoes.com. Retrieved 6 April.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "V for Vendetta". rogerebert.suntimes.com.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|acessdate=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "V for Vendetta". atthemovies.com. Retrieved 23 April.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "Jonathan on... V For Vendetta". BBC.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|acessdate=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "V for Vendetta". rte.ie. Retrieved 23 April.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|acessyear=ignored (help) - "A for Anarchy deleted scenes". aforanarchy.com. Retrieved 8 April.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "V for Vendetta Graphic Novel is a US Bestseller". televisionpoint.com. Retrieved 2 April.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "V for Vendetta". lewrockwell.com. Retrieved 20 March.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "Go See V for Vendetta". Antiwar.com. Retrieved 8 April.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "Time Warner promotes terrorism and anti-Christian bigotry in new leftist movie, 'V for Vendetta'". WorldNetDaily. March 17, 2006. Retrieved 4 April.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "The Media's War on the "War on Christians" Conference". frontpagemag. Retrieved 6 April.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "'Vendetta' a powerhouse". MichaelMoore.com. Retrieved 24 April.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "Confused, not thought through: V for Vendetta". world socialist website. Retrieved 27 March.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help)

External links

- The official V for Vendentta movie site & trailers

- V for Vendetta at IMDb

- V for Vendetta at Rotten Tomatoes

- Template:Msp

- Early V for Vendetta Script An undated early version of the V for Vendetta screenplay written by Larry and Andy Wachowski