This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Dwaipayanc (talk | contribs) at 15:38, 31 August 2012 (c/e, mostly according to the suggestion provided by Tony1 in FAC). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 15:38, 31 August 2012 by Dwaipayanc (talk | contribs) (c/e, mostly according to the suggestion provided by Tony1 in FAC)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)"Fifteenth of August" redirects here. For other uses, see August 15.

| Independence Day | |

|---|---|

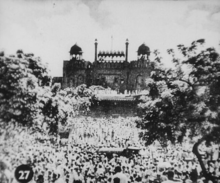

The national flag of India hoisted on the Red Fort in Delhi; hoisted flag is a common sight on public and private buildings on this national holiday. The national flag of India hoisted on the Red Fort in Delhi; hoisted flag is a common sight on public and private buildings on this national holiday. | |

| Observed by | |

| Type | National holiday |

| Celebrations | Flag hoisting, parades, singing patriotic songs and the national anthem, speech by the prime minister and president |

| Date | 15 August |

Independence Day, observed annually on 15 August, is a national holiday in India commemorating its independence from British rule on 15 August 1947. India attained freedom following an indepedence movement noted for largely peaceful nonviolent resistance and civil disobedience led by the Indian National Congress. The independence coincided with the partition of India in which the British Indian Empire was divided along religious lines into two new states—the Dominion of India (later the Republic of India) and the Dominion of Pakistan (later the Islamic Republic of Pakistan); the partition was accompanied by violent communal riots.

The flagship event in the Independence Day celebrations takes place in Delhi, where the prime minister hoists the national flag at the Red Fort and delivers a nationally broadcast speech from its ramparts. The holiday is observed all over India with flag-hoisting ceremonies, parades and cultural events. Indians celebrate the day by displaying the national flag on their attire, accessories, homes and vehicles; by listening to patriotic songs, watching patriotic movies; and bonding with family and friends. However, separatist and militant organisations have often carried out terrorist attacks on and around 15 August, and others have declared strikes and used black flags to boycott the celebration. Several books and films feature the independence and partition in their narrative.

History

Main article: Indian independence movementEuropean traders had established outposts in Indian subcontinent by the 17th century. Through their overwhelming military strength, the British East India company managed to subdue local kingdoms and establish themselves as the dominant colonial force by the 18th century. Following the Rebellion of 1857, the Government of India Act 1858 led the British Crown to assume direct control of India. In the decades following, public life gradually emerged all over India, the most notable example of which was the Indian National Congress, formed in 1885. The period after World War I was marked by British reforms such as the Montagu–Chelmsford Reforms, but it also witnessed the enactment of the repressive Rowlatt Act and strident calls for self-rule by Indian activists. The widespread discontent of this period crystallized into nationwide non-violent movements of non-cooperation and civil disobedience, of which Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi would become the leader and enduring symbol.

In the 1929 Lahore session of the Indian National Congress, the Purna Swaraj declaration, or "Declaration of the Independence of India" was promulgated, and 26 January was declared as India's Independence Day. The Congress called on people to pledge themselves to the civil disobedience movement and "to carry out the Congress instructions issued from time to time" until India attained complete independence from Great Britain. Celebration of such an Independence Day was planned to stoke nationalistic fervour among the Indian citizens, and to force the British government to consider India's independence on a more serious note.

During the 1930s, legislative reform was gradually enacted by the British; the Congress won victories in the resulting elections. The next decade was beset with political turmoil: Indian participation in World War II, the Congress's final push for non-cooperation, and an upsurge of Muslim nationalism led by the All-India Muslim League. The escalating political tension was capped by the advent of independence in 1947. The jubilation of independence was, however, tempered by the bloody partition of the subcontinent into two states: India and Pakistan.

Immediate background

In 1946, the Labour government in Britain, its exchequer exhausted by the recently concluded World War II, realised that it had neither the mandate at home, the international support, nor the reliability of native forces for continuing to control an increasingly restless India. In February 1947, Prime Minister Clement Attlee announced that the British government would grant full self-governance to British India by June 1948 at the latest.

The new viceroy, Louis Mountbatten, advanced the date for the transfer of power as he thought the continuous squabble between the Congress and the Muslim League might lead to a collapse of the interim government. He chose the second anniversary of Japan's surrender in World War II, 15 August, as the date of power transfer. The British government announced on 3 June 1947 that it had accepted the idea of partitioning British India into two states; the successor governments would be given dominion status and would have an implicit right to secede from the British Commonwealth. The Indian Independence Act 1947 (10 & 11 Geo 6 c. 30) of the Parliament of the United Kingdom partitioned British India into the two new independent dominions of India and Pakistan with effect from 15 August 1947, and granted complete legislative authority upon the respective constituent assemblies of the new countries. The Act received royal assent on 18 July 1947.

Partition and independence

Main article: Partition of IndiaMillions of Muslim, Sikh, and Hindu refugees trekked across the newly drawn borders. In Punjab, where the boredrs divided the Sikh regions in halves, massive bloodshed followed; in Bengal and Bihar, where Mahatma Gandhi's presence assuaged communal tempers, the violence was mitigated. In all, anywhere between 250,000 and 1,000,000 people on both sides of the new borders died in the violence. While the entire nation was celebrating the Independence Day, Gandhi decided to stay in Calcutta in an attempt to stem the communal carnage. On 14 August 1947, the Independence Day of Pakistan, the new Dominion of Pakistan came into being; Muhammad Ali Jinnah sworn in as its first Governor General in Karachi. At midnight, as India moved into 15 August 1947, Jawaharlal Nehru delivered the Tryst with destiny speech proclaiming India's independence.

Long years ago we made a tryst with destiny, and now the time comes when we shall redeem our pledge, not wholly or in full measure, but very substantially. At the stroke of the midnight hour, when the world sleeps, India will awake to life and freedom. A moment comes, which comes but rarely in history, when we step out from the old to the new, when an age ends, and when the soul of a nation, long suppressed, finds utterance. It is fitting that at this solemn moment, we take the pledge of dedication to the service of India and her people and to the still larger cause of humanity.

— Tryst with destiny speech, Jawaharlal Nehru, 15 August 1947

The Dominion of India became an independent country as official ceremonies took place in New Delhi in which Jawaharlal Nehru assumed the office as the first prime minister, and the viceroy, Lord Mountbatten, continued as its first governor general.

Celebration

Following the Purna Swaraj (Declaration of the Independence of India) promulgation in 1929, the Congress observed 26 January as the Independence Day between 1930 and 1947. The celebration was marked by meetings where the attendants took the "pledge of independence". Jawaharlal Nehru described in his autobiography that such meetings were peaceful, solemn, and "without any speeches or exhortation". Gandhi envisaged that besides the meetings, the day would be spent "... in doing some constructive work, whether it is spinning, or service of 'untouchables,' or reunion of Hindus and Mussalmans, or prohibition work, or even all these together". Following the actual independence in 1947, the Constitution of India came into effect on and from 26 January 1950; since then 26 January is celebrated as the Republic Day.

Independence Day, one of the three national holidays in India (the other two being the Republic Day on 26 January and Mohandas Gandhi's birthday on 2 October), is observed in all Indian states and union territories. On the eve of the Independence Day, the President of India delivers the "Address to the Nation", which is broadcasted nationally. On 15 August, the prime minister of India hoists the Indian flag on the ramparts of the historical site Red Fort in Delhi. Twenty-one gun shots are fired in honour of the solemn occasion. In his speech, the prime minister highlights the achievements of the country during the past year, raises important issues and gives a call for further development. He pays tribute to the leaders of the freedom struggle. The Indian national anthem, "Jana Gana Mana" is sung. The speech is followed by march past of divisions of the Indian Army and paramilitary forces. Parades and pageants showcase scenes from the freedom struggle and the various cultural traditions of India. Similar events take place in state capitals where the Chief Ministers of individual states unfurl the national flag, which is followed by parades and pageants.

Flag hoisting ceremonies and cultural programmes take place in governmental and non-governmental institutions throughout the country. Schools and colleges conduct flag hoisting ceremonies and various cultural events within their premises. Major government buildings are often adorned with strings of light. In Delhi and some other cities, kite flying is a celebratory event associated with the Independence Day. National flags of different sizes are used abundantly by the rejoicing residents to symbolise their allegiance to the country. Citizens adorn their cloths, wristbands, cars, household accessories with replicas of the tri-colour. Over a period of time, the celebration pattern has changed from a nationalistic one to a more relaxed, festive one, where friends and family bond and make merry.

The Indian diaspora celebrates the Independence Day in various parts of the world, particularly in regions with high concentration of non-resident Indians, with parades and pageants. In some locations, such as New York and other cities in the United States, 15 August has received the nomenclature "India Day" among the diaspora and the local populace. Pageants are held to celebrate "India Day" either on 15 August or a weekend day near 15 August.

Security threats

As early as three years after independence, the Naga National Council called for a boycott of Independence Day in the northeast. Separatist protests in this region intensified in the 1980s, and calls for boycotts, as well as terrorist attacks by insurgent organisations such as the United Liberation Front of Assam and the National Democratic Front of Bodoland, started to mar Independence Day celebrations. Separatist protesters have boycotted the Independence Day in Jammu and Kashmir with bandh (strikes), use of black flags and by burning the Indian national flag. Islamic terrorist outfits such as the Lashkar-e-Taiba, the Hizbul Mujahideen and the Jaish-e-Mohammed have issued threats, and have carried out attacks around Independence Day. Boycotting of the Independence Day celebration has also been called for by insurgent Maoist rebel organisations. In anticipation of terrorist attacks, particularly from Islamic militants, security measures in the country are intensified before the Independence Day celebration, especially in major cities such as Delhi, Mumbai and in troubled states such as Jammu and Kashmir. The airspace around the Red Fort is declared a no-fly zone during the celebration to prevent aerial attacks, and additional police forces are deployed in other cities.

In popular culture

On the Independence Day and the Republic Day, patriotic songs in Hindi and regional languages are broadcast on television and radio channels. They are also played alongside flag hoisting ceremonies. Patriotic films are broadcast on television channels. Over the decades, according to The Times of India, the number of such films broadcast has decreased as channels report that too many patriotic films overwhelm the viewers who want popular entertaining films instead, to enjoy the holiday. The population cohort that belong to the Generation Next often combine nationalism with popular culture during the celebrations. The mixture of popular culture with nationalism is exemplified by outfits and savouries dyed with the tricolour and designer garments that represent the various cultural traditions of India. Retail stores offer discounts on merchandise to promote sales at this time of year. The Times of India has described the commercialisation of patriotism as a negative facet.

Indian Postal Service has published commemorative stamps depicting independence movement leaders, nationalistic themes and defence-related themes on 15 August in several years. Independence and partition have inspired literary and other artistic creations in many languages. Such creations mostly describe the human cost of the partition where the day of independence forms a small part of their narrative. Salman Rushdie's novel Midnight's Children (1980), which won the Booker Prize and the Booker of Bookers, weaved its narrative based on the children born with magical abilities on midnight of 14–15 August 1947. Freedom at Midnight (1975) is a non-fiction work by Larry Collins and Dominique Lapierre that chronicled the events surrounding the first Independence Day celebrations in 1947. There is a paucity of films related to independence and partition, the majority of which highlight the circumstances of partition and its aftermath. On the Internet, Google has been commemorating the Independence Day by revamping the main page of its Indian version with a special doodle since 2003.

References

- Sarkar, Sumit (1983). Modern India, 1885–1947. Macmillan. p. 1–4. ISBN 978-0-333-90425-1.

- ^ Metcalf, B.; Metcalf, T. R. (9 October 2006). A Concise History of Modern India (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-68225-1.

- ^ Wolpert, Stanley A. (12 October 1999). India. University of California Press. p. 204. ISBN 978-0-520-22172-7. Retrieved 20 July 2012.

- Datta, V.N. (2006). "India's Independence Pledge". In Gandhi, Kishore (ed.). India's Date with Destiny. Allied Publishers. p. 34–39. ISBN 978-81-7764-932-1.

We recognise, however, that the most effective way of getting our freedom is not through violence. We will therefore prepare ourselves by withdrawing, so far as we can, all voluntary association from British Government, and will prepare for civil disobedience, including non-payment of taxes. We are convinced that if we can but withdraw our voluntary help and stop payment of taxes without doing violence, even under provocation; the need of his inhuman rule is assured. We therefore hereby solemnly resolve to carry out the Congress instructions issued from time to time for the purpose of establishing Purna Swaraj.

- ^ Guha, Ramachandra (12 August 2008). India After Gandhi: The History of the World's Largest Democracy. Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-06-095858-9. Retrieved 23 August 2012.

- Hyam, Ronald (2006). Britain's Declining Empire: the Road to Decolonisation, 1918–1968. Cambridge University Press. p. 106. ISBN 978-0-521-68555-9.

By the end of 1945, he and the Commander-in-chief, General Auckinleck were advising that there was a real threat in 1946 of large scale anti-British disorder amounting to even a well-organized rising aiming to expel the British by paralysing the administration.

...it was clear to Attlee that everything depended on the spirit and reliability of the Indian Army:"Provided that they do their duty, armed insurrection in India would not be an insoluble problem. If, however, the Indian Army was to go the other way, the picture would be very different.

...Thus, Wavell concluded, if the army and the police "failed" Britain would be forced to go. In theory, it might be possible to revive and reinvigorate the services, and rule for another fifteen to twenty years, but:It is a fallacy to suppose that the solution lies in trying to maintain the status quo. We have no longer the resources, nor the necessary prestige or confidence in ourselves. - Brown, Judith Margaret (1994). Modern India: the Origins of an Asian Democracy. Oxford University Press. p. 330. ISBN 978-0-19-873112-2.

India had always been a minority interest in British public life; no great body of public opinion now emerged to argue that war-weary and impoverished Britain should send troops and money to hold it against its will in an empire of doubtful value. By late 1946 both Prime Minister and Secretary of State for India recognized that neither international opinion nor their own voters would stand for any reassertion of the raj, even if there had been the men, money, and administrative machinery with which to do so

- Sarkar, Sumit (1983). Modern India, 1885–1947. Macmillan. p. 418. ISBN 978-0-333-90425-1.

With a war weary army and people and a ravaged economy, Britain would have had to retreat; the Labour victory only quickened the process somewhat.

- ^ Romein, Jan (1962). The Asian Century: a History of Modern Nationalism in Asia. University of California Press. p. 357. ASIN B000PVLKY4. Retrieved 24 July 2012.

- ^ Read, Anthony; Fisher, David (1 July 1999). The Proudest Day: India's Long Road to Independence. W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 459–60. ISBN 978-0-393-31898-2. Retrieved 4 August 2012.

- "Indian Independence Act 1947". The National Archives, Her Majesty's Government. Retrieved 17 July 2012.

- DeRouen, Karl; Heo, Uk. Civil Wars of the World: Major Conflicts since World War II. ABC-CLIO. pp. 408–414. ISBN 978-1-85109-919-1. Retrieved 24 July 2012.

- Alexander, Horace (1 August 2007). "A miracle in Calcutta". Prospect. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- "Jawaharlal Nehru (1889-1964): Speech On the Granting of Indian Independence, August 14, 1947". Fordham University. Retrieved 26 07 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - Vohra, Ranbir (2001). The Making of India: a Historical Survey. M.E. Sharpe. p. 148. ISBN 978-0-7656-0711-9. Retrieved 20 July 2012.

- Ramaseshan, Radhika (26 January 2012). "Why January 26: the History of the Day". The Telegraph. Retrieved 19 July 2012.

- Nehru, Jawaharlal (1989). Jawaharlal Nehru, An Autobiography: With Musings on Recent Events in India. Bodley Head. p. 209. ISBN 978-0-370-31313-9. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- Gandhi, (Mahatma) (1970). Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi. Vol. 42. Publications Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. pp. 398–400. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- ^ "Independence Day". Government of India. Retrieved 18 July 2012.

- "India Celebrates Its 66th Independence Day". Outlook. 15 August 2012. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- "Barring Northeast, Peaceful I-Day Celebrations across India (State Roundup, Combining Different Series)". Monsters and Critics. 15 August 2007. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- ^ Gupta, K.R.; Gupta, Amita (1 January 2006). Concise Encyclopaedia of India. Atlantic Publishers. p. 1002. ISBN 978-81-269-0639-0. Retrieved 20 July 2012.

- "Independence Day Celebration". Government of India. Retrieved 17 July 2012.

- Bhattacharya, Suryatapa (15 August 2011). "Indians Still Battling it out on Independence Day". The National. Retrieved 20 July 2012.

- ^ "When India Wears its Badge of Patriotism with Pride". DNA. 15 August 2007. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- ^ Ansari, Shabana (15 August 2011). "Independence Day: For GenNext, It's Cool to Flaunt Patriotism". DNA. Retrieved 20 July 2012.

- Dutta Sachdeva, Sujata; Mathur, Neha (14 August 2005). "It's Cool to Be Patriotic: GenNow". The Times of India. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- "Indian-Americans Celebrate Independence Day". The Hindu. 16 August 2010. Retrieved 18 July 2012.

- Ghosh, Ajay (2008). "India's Independence Day Celebrations across the United States—Showcasing India's Cultural Diversity and Growing Economic Growth". NRI Today. Retrieved 20 July 2012.

- Sharma, Suresh K. (2006). Documents on North-East India: Nagaland. Mittal Publications. pp. 146, 165. ISBN 978-81-8324-095-6. Retrieved 30 August 2012.

- Mazumdar, Prasanta (11 August 2011). "ULFA's Independence Day Gift for India: Blasts". DNA. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- Office of the Coordinator for Counterterrorism. Country Reports on Terrorism 2004. United States Department of State. p. 129. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- Schendel, Willem Van; Abraham, Itty (2005). Illicit Flows and Criminal Things: States, Borders, and the Other Side of Globalization. Indiana University Press. pp. 55–56. ISBN 978-0-253-21811-7. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- "Rebels Call for I-Day Boycott in Northeast". Rediff. 10 August 2010. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- Biswas, Prasenjit; Suklabaidya, Chandan (6 February 2008). Ethnic Life-Worlds in North-East India: an Analysis. SAGE. p. 233. ISBN 978-0-7619-3613-8. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- Thakuria, Nava (5 September 2011). "Appreciating the Spirit of India's Independence Day". Global Politician. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- "Kashmir Independence Day Clashes". BBC. 15 August 2008. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- Behera, Navnita Chadha. Demystifying Kashmir. Pearson Education India. p. 146. ISBN 978-81-317-0846-0. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- Das, Suranjan (1 August 2001). Kashmir and Sindh: Nation-Building, Ethnicity and Regional Politics in South Asia. Anthem Press. p. 49. ISBN 978-1-898855-87-3. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- Viswam, Deepa (1 January 2010). Role of Media in Kashmir Crisis. Gyan Publishing House. pp. 167–168. ISBN 978-81-7835-862-8. Retrieved 25 August 2012.

- "LeT, JeM Plan Suicide Attacks in J&K on I-Day". The Economic Times. 14 August 2002. Retrieved 25 August 2012.

- "Ayodhya Attack Mastermind Killed in Jammu". OneIndia News. 11 August 2007. Retrieved 25 August 2012.

- "LeT to Hijack Plane Ahead of Independence Day?". The First Post. 12 August 2012. Retrieved 25 August 2012.

- "Two Hizbul Militants Held in Delhi". NDTV. 7 August 2009. Retrieved 25 August 2012.

- "Maoist Boycott Call Mars I-Day Celebrations in Orissa". The Hindu. 15 August 2011. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- Verma, Bharat (1 June 2012). Indian Defence Review Vol. 26.2: Apr-Jun 2011. Lancer Publishers. p. 111. ISBN 978-81-7062-219-2. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- Ramgopal, Ram (14 August 2002). "India Braces for Independence Day". CNN. Retrieved 18 July 2012.

- "US Warns of India Terror Attacks". BBC. 11 August 2006. Retrieved 18 July 2012.

- "Rain Brings Children Cheer, Gives Securitymen a Tough Time". The Hindu. 16 August 2011. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- "India Heightens Security ahead of I-Day". The Times of India. 14 August 2006. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ^ Nayar, Pramod K. (14 June 2006). Reading Culture: Theory, Praxis, Politics. SAGE. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-7619-3474-5. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- Pant, Nikhila; Pasricha, Pallavi (26 January 2008). "Patriotic Films, Anyone?". The Times of India. Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- Vohra, Meera; Shashank Tripathi (14 August 2012). "Fashion fervour gets tri-coloured!". Times of India. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

- ^ Sharma, Kalpana (13 August 2010). "Pop Patriotism—Is Our Azaadi on Sale?". The Times of India. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- Basu, Sreeradha D; Mukherjee, Writankar (14 August 2010). "Retail Majors Flag Off I-Day Offers to Push Sales". The Economic Times. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- Chatterjee, Sudeshna (16 August 1997). "The Business of Patriotism". The Indian Express. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- Sinha, Partha (18 September 2007). "Commercial Patriotism Rides New Wave of Optimism". The Economic Times. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- "Indian Postage Stamps Catalogue 1947–2011" (PDF). India Post. Retrieved 28 August 2012.

- Cleary, Joseph N. (3 January 2002). Literature, Partition and the Nation-State: Culture and Conflict in Ireland, Israel and Palestine. Cambridge University Press. p. 104. ISBN 978-0-521-65732-7. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

The partition of India figures in a goo deal of imaginative writing...

- Bhatia, Nandi (1996). "Twentieth Century Hindi Literature". In Natarajan, Nalini (ed.). Handbook of Twentieth-Century Literatures of India. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 146–147. ISBN 978-0-313-28778-7. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ^ Roy, Rituparna (15 July 2011). South Asian Partition Fiction in English: From Khushwant Singh to Amitav Ghosh. Amsterdam University Press. pp. 24–29. ISBN 978-90-8964-245-5. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ^ Mandal, Somdatta (2008). "Constructing Post-partition Bengali Cultural Identity through Films". In Bhatia, Nandi; Roy, Anjali Gera (eds.). Partitioned Lives: Narratives of Home, Displacement, and Resettlement. Pearson Education India. pp. 66–69. ISBN 978-81-317-1416-4. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1080/03068374.2010.508231, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1080/03068374.2010.508231instead. (subscription required) - Sarkar, Bhaskar (29 April 2009). Mourning the Nation: Indian Cinema in the Wake of Partition. Duke University Press. p. 121. ISBN 978-0-8223-4411-7. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- Vishwanath, Gita; Malik, Salma (2009). "Revisiting 1947 through Popular Cinema: a Comparative Study of India and Pakistan" (PDF). Economic and Political Weekly. XLIV (36): 61–69. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- Raychaudhuri, Anindya (2009). "Resisting the Resistible: Re-writing Myths of Partition in the Works of Ritwik Ghatak". Social Semiotics. 19 (4): 469–481. doi:10.1080/10350330903361158.(subscription required)

- "Google doodles Independence Day India". CNN-IBN. 15 August 2012. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

External links

- Indian Independence Day at Government of India website

- Indian Independence Day in Encyclopædia Britannica Blog