This is an old revision of this page, as edited by PBS (talk | contribs) at 00:01, 18 May 2006 (→Opposition to use of atomic bombs: Removed article 25, see talk page). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 00:01, 18 May 2006 by PBS (talk | contribs) (→Opposition to use of atomic bombs: Removed article 25, see talk page)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| Editing of this article by new or unregistered users is currently disabled. See the protection policy and protection log for more details. If you cannot edit this article and you wish to make a change, you can submit an edit request, discuss changes on the talk page, request unprotection, log in, or create an account. |

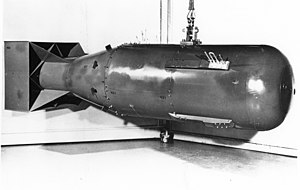

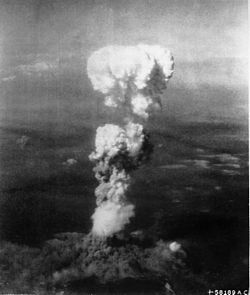

On the morning of August 6, 1945 the United States Army Air Forces dropped the nuclear weapon "Little Boy" on the city of Hiroshima, followed three days later by the detonation of the "Fat Man" bomb over Nagasaki, Japan. In his 1999 book Downfall, historian Richard Frank analyzed the many widely varying estimates of casualties caused by the bombings. He concluded "The best approximation is that the number is huge and falls between 100,000 and 200,000." Most of the casualties were civilians.

The role of the bombings in Japan's surrender, as well as the effects and justification of them, have been subject to much debate. In the U.S., the prevailing view is that the bombings ended the war months sooner than would otherwise have been the case, saving many lives that would have been lost on both sides if the planned invasion of Japan had taken place. In Japan, the general public tends to think that the bombings were needless as the preparation for the surrender was in progress in Tokyo.

Prelude to the bombings

The United States, with assistance from the United Kingdom and Canada, designed and built the bombs under the codename Manhattan Project; initially for use against Nazi Germany and inspired by the correct assumption that Germany would also conduct an atomic bomb project (suggested by Albert Einstein), and incorrect assumption that the Nazis held a lead in atomic weapons research. The first nuclear device, called "Gadget," was detonated at the Trinity test site near Alamogordo, New Mexico on July 16, 1945. The Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombs were the second and third to be detonated and the only ones ever employed as weapons.

Hiroshima and Nagasaki weren't the first times that the Allies had bombed Axis cities without specifically targeting military installations, nor the first time that such bombings had caused huge numbers of civilian casualties, nor the first time that such bombings were (or came to be) controversial. In Germany, the Allied firebombing of Dresden resulted in roughly 30,000 deaths. The March 1945 firebombing of Tokyo may have killed as many as 100,000 people. By August, about 60 Japanese cities had been destroyed through a massive aerial campaign, including large firebombing raids on the cities of Tokyo and Kobe.

Over 3½ years of direct U.S. involvement in World War II, approximately 400,000 American lives had been lost, roughly half of them incurred in the war against Japan. In the months prior to the bombings, the Battle of Okinawa resulted in an estimated 50–150,000 civilian deaths, 100–125,000 Japanese or Okinawan military or conscript deaths and over 72,000 American casualties. An invasion of Japan was expected to result in casualties many times greater than in Okinawa.

U.S. President Harry S. Truman, who was unaware of the Manhattan Project until Franklin Roosevelt's death, made the decision to drop the bombs on Japan. His stated intention in ordering the bombings was to bring about a quick resolution of the war by inflicting destruction, and instilling fear of further destruction, that was sufficient to cause Japan to surrender. On July 26 Truman and other allied leaders issued The Potsdam Declaration outlining terms of surrender for Japan:

- "...The might that now converges on Japan is immeasurably greater than that which, when applied to the resisting Nazis, necessarily laid waste to the lands, the industry and the method of life of the whole German people. The full application of our military power, backed by our resolve, will mean the inevitable and complete destruction of the Japanese armed forces and just as inevitably the utter devastation of the Japanese homeland..."

- "...We call upon the government of Japan to proclaim now the unconditional surrender of all Japanese armed forces, and to provide proper and adequate assurances of their good faith in such action. The alternative for Japan is prompt and utter destruction."

The next day, Japanese papers reported that the declaration, the text of which had been broadcast and dropped on leaflets into Japan, had been rejected. The atomic bomb was still a highly guarded secret and not mentioned in the declaration.

Choice of targets

The Target Committee at Los Alamos on May 10–11, 1945, recommended Kyoto, Hiroshima, Yokohama and the arsenal at Kokura as possible targets. The committee rejected the use of the weapon against a strictly military objective due to the chance of missing a small target not surrounded by a larger urban area. The psychological effects on Japan were of great importance to the committee members. They also agreed that the initial use of the weapon should be sufficiently spectacular for its importance to be internationally recognized. The committee felt Kyoto, as an intellectual center of Japan, had a population "better able to appreciate the significance of the weapon." Hiroshima was chosen due to its large size, its being "an important army depot" and the potential that the bomb would cause greater destruction due to its being surrounded by hills which would have a "focusing effect".

Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson struck Kyoto from the list because of its cultural significance, over the objections of Gen. Leslie Groves, head of the Manhattan Project. According to Professor Edwin O. Reischauer, Stimson "had known and admired Kyoto ever since his honeymoon there several decades earlier." On July 25 General Carl Spaatz was ordered to bomb one of the targets: Hiroshima, Kokura, Niigata or Nagasaki as soon after August 3 as weather permitted, and the remaining cities as additional weapons became available.

Hiroshima

Hiroshima during World War II

At the time of its bombing, Hiroshima was a city of considerable industrial and military significance. Even some military camps were located nearby, such as the headquarters of the Fifth Division and Field Marshal Shunroku Hata's 2nd General Army Headquarters, which commanded the defense of all of southern Japan. Hiroshima was a minor supply and logistics base for the Japanese military. The city was a communications center, a storage point, and an assembly area for troops. It was one of several Japanese cities left deliberately untouched by American bombing, allowing an ideal environment to measure the damage caused by the atomic bomb. Another account stresses that after General Spaatz reported that Hiroshima was the only targeted city without POW-camps, Washington decided to assign it highest priority.

The center of the city contained a number of reinforced concrete buildings and lighter structures. Outside the center, the area was congested by a dense collection of small wooden workshops set among Japanese houses. A few larger industrial plants lay near the outskirts of the city. The houses were of wooden construction with tile roofs, and many of the industrial buildings also were of wood frame construction. The city as a whole was highly susceptible to fire damage.

The population of Hiroshima had reached a peak of over 381,000 earlier in the war, but prior to the atomic bombing the population had steadily decreased because of a systematic evacuation ordered by the Japanese government. At the time of the attack the population was approximately 255,000. This figure is based on the registered population used by the Japanese in computing ration quantities, and the estimates of additional workers and troops who were brought into the city may be inaccurate.

The bombing

Hiroshima was the primary target of the first U.S. nuclear attack mission, on August 6, 1945. The B-29 Enola Gay, piloted and commanded by Colonel Paul Tibbets, was launched from Tinian airbase in the West Pacific, approximately 6 hours' flight time away from Japan. The drop date of the 6th was chosen because there had previously been a cloud formation over the target. At the time of launch, the weather was good, and the crew and equipment functioned properly. Navy Captain William Parsons armed the bomb during the flight, since it had been left unarmed to minimize the risks during takeoff. In every detail, the attack was carried out exactly as planned, and the gravity bomb, a gun-type fission weapon, with 60 kg (130 pounds) of uranium-235, performed precisely as expected.

About an hour before the bombing, the Japanese early warning radar net detected the approach of some American aircraft headed for the southern part of Japan. The alert had been given and radio broadcasting stopped in many cities, among them Hiroshima. The planes approached the coast at a very high altitude. At nearly 08:00, the radar operator in Hiroshima determined that the number of planes coming in was very small—probably not more than three—and the air raid alert was lifted. (To save gasoline, the Japanese had decided not to intercept small formations, which were assumed to be weather planes.) The three planes present were the Enola Gay (named after Colonel Tibbets' mother), The Great Artiste (a recording and surveying craft), and a then-nameless plane later called Necessary Evil (the photographing plane). The normal radio broadcast warning was given to the people that it might be advisable to go to air-raid shelters if B-29s were actually sighted, but no raid was expected beyond some sort of reconnaissance. At 08:15, the Enola Gay dropped the nuclear bomb called "Little Boy" over the center of Hiroshima. It exploded about 600 meters (2,000 feet) above the city with a blast equivalent to 13 kilotons of TNT, killing an estimated 70,000–80,000 people. At least 11 U.S. POWs also died. Infrastructure damage was estimated at 90% of Hiroshima's buildings being either damaged or completely destroyed.

Japanese realization of the bombing

The Tokyo control operator of the Japanese Broadcasting Corporation noticed that the Hiroshima station had gone off the air. He tried to re-establish his program by using another telephone line, but it too had failed. About twenty minutes later the Tokyo railroad telegraph center realized that the main line telegraph had stopped working just north of Hiroshima. From some small railway stops within ten miles (16 km) of the city came unofficial and confused reports of a terrible explosion in Hiroshima. All these reports were transmitted to the Headquarters of the Japanese General Staff.

Military bases repeatedly tried to call the Army Control Station in Hiroshima. The complete silence from that city puzzled the men at Headquarters; they knew that no large enemy raid had occurred and that no sizeable store of explosives was in Hiroshima at that time. A young officer of the Japanese General Staff was instructed to fly immediately to Hiroshima, to land, survey the damage, and return to Tokyo with reliable information for the staff. It was generally felt at Headquarters that nothing serious had taken place, that it was all a terrible rumor starting from a few sparks of truth.

The staff officer went to the airport and took off for the southwest. After flying for about three hours, while still nearly 100 miles (160 km) from Hiroshima, he and his pilot saw a great cloud of smoke from the bomb. In the bright afternoon, the remains of Hiroshima were burning. Their plane soon reached the city, around which they circled in disbelief. A great scar on the land still burning, and covered by a heavy cloud of smoke, was all that was left. They landed south of the city, and the staff officer, after reporting to Tokyo, immediately began to organize relief measures.

Tokyo's first knowledge of what had really caused the disaster came from the White House public announcement in Washington, sixteen hours after the nuclear attack on Hiroshima.

Radiation poisoning and/or necrosis caused illness and death after the bombing in about 1% of those who survived the initial explosion. By the end of 1945, thousands more people died due to radiation poisoning, bringing the total killed in Hiroshima in 1945 to about 90,000. Since then about a thousand more people have died of radiation-related causes. (According to the city of Hiroshima, as of August 6, 2005, the cumulative death toll among Hiroshima's atomic-bomb victims was 242,437. That figure includes everyone who was in the city when the bomb exploded, or was later exposed to fallout, who has since died.)

Survival of some structures

Some of the reinforced concrete buildings in Hiroshima were very strongly constructed because of the earthquake danger in Japan, and their framework did not collapse even though they were fairly close to the center of damage in the city. As the bomb detonated in the air, the blast was more downward than sideways, which was largely responsible for the survival of the Prefectural Industrial Promotional Hall, now commonly known as the Genbaku, or A-bomb Dome designed and built by the Czech architect Jan Letzel, which was only a few meters from ground zero. (The ruin was named Hiroshima Peace Memorial and made a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1996 over the objections of the U.S. and China.)

Events of August 7-9

After the Hiroshima bombing, President Truman announced, "If they do not now accept our terms, they may expect a rain of ruin from the air the likes of which has never been seen on this earth." On August 8, 1945, leaflets were dropped and warnings were given to Japan by Radio Saipan. (The area of Nagasaki did not receive warning leaflets until August 10, though the leaflet campaign covering the whole country was over a month into its operations.) An English translation of that leaflet is available at PBS.

At one minute past midnight on August 9, Tokyo time, Russian infantry, armor, and air forces launched an invasion of Manchuria. Four hours later, word reached Tokyo that the Soviet Union had broken the neutrality pact and declared war on Japan. The senior leadership of the Japanese Army took the news in stride, grossly underestimating the scale of the attack. They did start preparations to impose martial law on the nation, with the support of Minister of War Anami, in order to stop anyone attempting to make peace.

Responsibilty for the timing of the second bombing was delegated to Colonel Tibbets as commander of the 509th Composite Group on Tinian. Scheduled for August 11 against Kokura, the raid was moved forward to avoid a five day period of bad weather forecast to begin on the 10th.

Nagasaki

Nagasaki during World War II

The city of Nagasaki had been one of the largest sea ports in southern Japan and was of great wartime importance because of its wide-ranging industrial activity, including the production of ordnance, ships, military equipment, and other war materials.

In contrast to many modern aspects of Nagasaki, the bulk of the residences were of old-fashioned Japanese construction, consisting of wood or wood-frame buildings, with wood walls (with or without plaster), and tile roofs. Many of the smaller industries and business establishments were also housed in buildings of wood or other materials not designed to withstand explosions. Nagasaki had been permitted to grow for many years without conforming to any definite city zoning plan; residences were erected adjacent to factory buildings and to each other almost as closely as possible throughout the entire industrial valley.

Nagasaki had never been subjected to large-scale bombing prior to the explosion of a nuclear weapon there. On August 1, 1945, however, a number of conventional high-explosive bombs were dropped on the city. A few hit in the shipyards and dock areas in the southwest portion of the city, several hit the Mitsubishi Steel and Arms Works and six bombs landed at the Nagasaki Medical School and Hospital, with three direct hits on buildings there. While the damage from these bombs was relatively small, it created considerable concern in Nagasaki and a number of people—principally school children—were evacuated to rural areas for safety, thus reducing the population in the city at the time of the nuclear attack.

To the north of Nagasaki there was a camp holding British prisoners of war. They were working in the coal mines so consequently only found out about the bombing when they came to the surface. For them, it was the bomb that saved their lives. However at least eight known POWs were casualities.

The bombing

On the morning of August 9, 1945, the crew of the American B-29 Superfortress Bock's Car, flown by Major Charles W. Sweeney and carrying the nuclear bomb code-named "Fat Man," found their primary target, Kokura, to be obscured by clouds. After three runs over the city and having fuel running low due to a fuel-transfer problem, they headed for their secondary target, Nagasaki. At about 07:50 Japanese time, an air raid alert was sounded in Nagasaki, but the "all clear" signal was given at 08:30. When only two B-29 Superfortresses were sighted at 10:53 the Japanese apparently assumed that the planes were only on reconnaissance and no further alarm was given.

A few minutes later, at 11:00, the observation B-29 (The Great Artiste flown by Captain Frederick C. Bock) dropped instruments attached to three parachutes. These instruments also contained messages to Prof. Ryokichi Sagane, a nuclear physicist at the University of Tokyo who studied with three of the scientists responsible for the atomic bomb at the University of California, Berkeley, urging him to tell the public about the danger involved with these weapons of mass destruction. The messages were found by military authorities, but not turned over to Sagane.

At 11:02, a last minute break in the clouds over Nagasaki allowed Bock's Car's bombardier, Captain Kermit Beahan, to visually sight the target as ordered. The "Fat Man" weapon, containing a core of ~6.4 kg of plutonium-239, was dropped over the city's industrial valley. It exploded 469 meters (1,540 feet) above the ground exactly halfway between the Mitsubishi Steel and Arms Works in the south and the Mitsubishi-Urakami Ordnance Works (Torpedo Works) in the north. This was nearly two miles northwest of the planned hypocenter; the blast was confined to the Urakami Valley and a major portion of the city was protected by the intervening hills.

According to most estimates, about 40,000 of Nagasaki's 240,000 residents were killed instantly, and over 25–60,000 were injured. The total number of residents killed is believed to be perhaps as many as 80,000, including those who died from radiation poisoning in the following months.

The hibakusha

The survivors of the bombings are called hibakusha (被爆者), a Japanese word that literally translates to "people exposed to the bomb". The suffering of the bombing is the root of Japan's postwar pacifism, and the nation has sought the abolition of nuclear weapons from the world ever since. As of 2006, there are about 266,000 hibakusha still living in Japan.

Debate over the bombings

Support for use of atomic bombs

Although supporters of the bombing concede that the civilian leadership in Japan was cautiously and discreetly sending out diplomatic communiques as far back as January 1945, following the Allied invasion of Luzon in the Philippines, they point out that Japanese military officials were unanimously opposed to any negotiations before the use of the atomic bomb.

While some members of the civilian leadership did use covert diplomatic channels to begin negotiation for peace, on their own they could not negotiate surrender or even a cease-fire. Japan, as a Constitutional Monarchy, could only enter into a peace agreement with the unanimous support of the Japanese cabinet, and this cabinet was dominated by militarists from the Japanese Imperial Army and the Japanese Imperial Navy, all of whom were initially opposed to any peace deal. A political stalemate developed between the military and civilian leaders of Japan with the military increasingly determined to fight despite the costs and odds. Many continued to believe that Japan could negotiate more favorable terms of surrender by continuing to inflict high levels of casualties on opposing forces, and end the war without an occupation of Japan or a change of government.

Historian Victor Davis Hanson points to the increased Japanese resistance, futile though it was in retrospect, as it became more and more obvious that the result of the war could not be overturned by the Axis powers. The Battle of Okinawa showed this determination to fight on at all costs. More than 120,000 Japanese and 18,000 American troops were killed in the bloodiest battle of the Pacific theater, just 8 weeks before Japan's final surrender. In fact, more civilians died in the Battle of Okinawa than did in the initial blast of the atomic bombings. When the Soviet Union declared war on Japan on August 8, 1945, and carried out Operation August Storm, the Japanese Imperial Army ordered its ill-supplied and weakened forces in Manchuria to fight to the last man. Major General Masakazu Amanu, chief of the operations section at Japanese Imperial Headquarters, stated that he was absolutely convinced his defensive preparations, begun in early 1944, could repel any Allied invasion of the home islands with minimal losses. The Japanese would not give up easily because of their strong tradition of pride and honor—many followed the Samurai code and would fight until the very last man was dead.

After the realization that the destruction of Hiroshima was from a nuclear weapon, the civilian leadership gained more and more traction in its argument that Japan had to concede defeat and accept the terms of the Potsdam Declaration. Even after the destruction of Nagasaki, the Emperor himself needed to intervene to end a deadlock in the cabinet.

According to some Japanese historians, Japanese civilian leaders who favored surrender saw their salvation in the atomic bombing. The Japanese military was steadfastly refusing to give up, as were the military men in the war cabinet. (Because the cabinet functioned by consensus, even one holdout could prevent it from accepting the Declaration.) Thus the peace faction seized on the bombing as a new argument to force surrender. Koichi Kido, one of Emperor Hirohito's closest advisors, stated: "We of the peace party were assisted by the atomic bomb in our endeavor to end the war." Hisatsune Sakomizu, the chief Cabinet secretary in 1945, called the bombing "a golden opportunity given by heaven for Japan to end the war." According to these historians and others, the pro-peace civilian leadership was able to use the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki to convince the military that no amount of courage, skill and fearless combat could help Japan against the power of atomic weapons. Akio Morita, founder of Sony and a Japanese Naval officer during the war, also concludes that it was the atomic bomb and not conventional bombings from B-29s that convinced the Japanese military to agree to peace.

Supporters of the bombing also point out that waiting for the Japanese to surrender was not a cost-free option—as a result of the war, noncombatants were dying throughout Asia at a rate of about 200,000 per month. The firebombing had killed well over 100,000 people in Japan, since February of 1945, directly and indirectly. That intensive conventional bombing would have continued prior to an invasion. The submarine blockade and the United States Army Air Forces's mining operation, Operation Starvation, had effectively cut off Japan's imports. A complementary operation against Japan's railways was about to begin, isolating the cities of southern Honshu from the food grown elsewhere in the Home Islands. This, combined with the delay in relief supplies from the Allies, could have resulted in a far greater death toll in Japan, due to famine and malnutrition, than actually occurred in the attacks. "Immediately after the defeat, some estimated that 10 million people were likely to starve to death," noted historian Daikichi Irokawa. Meanwhile, in addition to the Soviet attacks, offensives were scheduled for September in southern China, and Malaysia.

The Americans anticipated losing many soldiers in the planned invasion of Japan, although the actual number of expected fatalities and wounded is subject to some debate and depends on the persistence and reliability of Japanese resistance and whether the Americans would have invaded only Kyushu in November 1945 or if a follow up landing near Tokyo, projected for March of 1946 would have been needed. Years after the war, Secretary of State James Byrnes claimed that 500,000 American lives would have been lost—and that number has since been repeated authoritatively, but in the summer of 1945, U.S. military planners projected 20,000–110,000 combat deaths from the initial November 1945 invasion, with about three to four times that number wounded. (Total U.S. combat deaths on all fronts in World War II in nearly four years of war were 292,000.) However, these estimates were done using intelligence that grossly underestimated Japanese strength being gathered for the battle of Kyushu in numbers of soldiers and kamikazes, by factors of at least three. Many military advisors held that a worst-case scenario could involve up to 1,000,000 American casualties.

In addition to that, the atomic bomb hastened the end of the Second World War in Asia liberating hundreds of thousands of Western citizens, including about 200,000 Dutch and 400,000 Indonesians ("Romushas") from Japanese concentration camps. Moreover, Japanese troops had committed atrocities against millions of civilians (such as the infamous Nanking Massacre), and the early end to the war prevented futher bloodshed.

Supporters also point to an order given by the Japanese War Ministry on August 1, 1944. The order dealt with the disposal and execution of all Allied POWs, numbering over 100,000, if an invasion of the Japanese mainland took place. (It is also likely that, considering Japan's previous treatment of POWs, were the Allies to wait out Japan and starve it, the Japanese would have killed all Allied POWs and Chinese prisoners.)

In response to the argument that the large-scale killing of civilians was immoral and a war crime, supporters of the bombings have argued that the Japanese government waged total war, ordering many civilians (including women and children) to work in factories and military offices and to fight against any invading force. Father John A. Siemes, professor of modern philosophy at Tokyo's Catholic University, and an eyewitness to the atomic bomb attack on Hiroshima wrote:

- "We have discussed among ourselves the ethics of the use of the bomb. Some consider it in the same category as poison gas and were against its use on a civil population. Others were of the view that in total war, as carried on in Japan, there was no difference between civilians and soldiers, and that the bomb itself was an effective force tending to end the bloodshed, warning Japan to surrender and thus to avoid total destruction. It seems logical to me that he who supports total war in principle cannot complain of war against civilians."

As an additional argument against the charge of war crimes, some supporters of the bombings have emphasized the strategic significance of Hiroshima, as the Japanese 2nd army's headquarters, and of Nagasaki, as a major munitions manufacturing center.

Some historians have claimed that U.S. planners also wanted to end the war quickly to minimize potential Soviet acquisition of Japanese-held territory.

Finally, supporters also point to Japanese plans, devised by their Unit 731 to launch Kamikaze planes laden with plague-infested fleas to infect the populace of San Diego, California. The target date was to be September 22, 1945, although it is unlikely that the Japanese government would have allowed so many resources to be diverted from defensive purposes.

Opposition to use of atomic bombs

The Manhattan Project had originally been conceived as a counter to Nazi Germany's atomic bomb program, and with the defeat of Germany, several scientists working on the project felt that the United States should not be the first to use such weapons. Two of the prominent critics of the bombings were Albert Einstein and Leo Szilard, who had together spurred the first bomb research in 1939 with a jointly written letter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Szilard, who had gone on afterwards to play a major role in the Manhattan Project, argued: "If the Germans had dropped atomic bombs on cities instead of us, we would have defined the dropping of atomic bombs on cities as a war crime, and we would have sentenced the Germans who were guilty of this crime to death at Nuremberg and hanged them." In the days just before their use, many scientists (including American nuclear physicist Edward Teller) argued that the destructive power of the bomb could have been demonstrated without the taking of lives.

The existence of historical accounts which indicate that the decision to use the atomic bombs was made in order to provoke an early surrender of Japan by use of an awe-inspiring power, coupled with the observation that the bombs were purposefully used upon targets which included civilians, has caused some commentators to observe that the incident was an act of state terrorism. Historian Robert Newman, who is in favor of the decision to drop the bombs, took the claim of state terrorism seriously enough to argue that the practice of terrorism is justified in some cases.

Some have claimed that the Japanese were already essentially defeated, and therefore use of the bombs was unnecessary. General Dwight D. Eisenhower so advised the Secretary of War, Henry L. Stimson, in July of 1945. The highest-ranking officer in the Pacific Theater, General Douglas MacArthur, was not consulted beforehand, but said afterward that he felt that there was no military justification for the bombings. The same opinion was expressed by Fleet Admiral William D. Leahy (the Chief of Staff to the President), General Carl Spaatz (commander of the U.S. Strategic Air Forces in the Pacific), and Brigadier General Carter Clarke (the military intelligence officer who prepared intercepted Japanese cables for U.S. officials); Major General Curtis LeMay; and Admiral Ernest King, U.S. Chief of Naval Operations, Undersecretary of the Navy Ralph A. Bard , and Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, Commander in Chief of the Pacific Fleet.

- Eisenhower wrote in his memoir The White House Years:

- "In 1945 Secretary of War Stimson, visiting my headquarters in Germany, informed me that our government was preparing to drop an atomic bomb on Japan. I was one of those who felt that there were a number of cogent reasons to question the wisdom of such an act. During his recitation of the relevant facts, I had been conscious of a feeling of depression and so I voiced to him my grave misgivings, first on the basis of my belief that Japan was already defeated and that dropping the bomb was completely unnecessary, and secondly because I thought that our country should avoid shocking world opinion by the use of a weapon whose employment was, I thought, no longer mandatory as a measure to save American lives."

The United States Strategic Bombing Survey, after interviewing hundreds of Japanese civilian and military leaders after Japan surrendered, reported:

- "Based on a detailed investigation of all the facts, and supported by the testimony of the surviving Japanese leaders involved, it is the Survey's opinion that certainly prior to 31 December 1945, and in all probability prior to 1 November 1945, Japan would have surrendered even if the atomic bombs had not been dropped, even if Russia had not entered the war, and even if no invasion had been planned or contemplated."

However, it should be noted that the survey assumed that continued conventional attacks on Japan—with additional direct and indirect casualties—would be needed to force surrender by the November or December dates mentioned.

Others contend that Japan had been trying to surrender for at least two months, but the U.S. refused by insisting on an unconditional surrender. In fact, while several diplomats favored surrender, the leaders of the Japanese military were committed to fighting a "decisive battle" on Kyushu, hoping that they could negotiate better terms for an armistice afterward—all of which the Americans knew from reading decrypted Japanese communications. The Japanese government never did decide what terms, beyond preservation of an imperial system, they would have accepted to end the war; as late as August 9, the Supreme Council was still split, with the hardliners insisting Japan should demobilize its own forces, no war crimes trials, and no occupation. Only the direct intervention of the Emperor ended the dispute, and even after that a military coup was attempted to prevent the surrender.

There is also some question as to how much Truman knew about the initial bombing. In his diary, he states that he told Sec. of War Stimson "to use it so that military objectives and soldiers and sailors are the target, not men, women, and children", and that they were in accord that "the target will be a purely military one" . Immediately after the bombing, Truman gave a speech stating, "The world will note that the first atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, a military base. That was because we wished in this first attack to avoid, insofar as possible, the killing of civilians," seemingly not realizing that Hiroshima was a major city.

Another criticism is that the U.S. should have waited a short time to gauge the effect of the Soviet Union's entry into the war. The U.S. knew, as Japan did not, that the Soviet Union had agreed to declare war on Japan three months after V-E Day; such an attack was indeed launched on August 8, 1945. The loss of any possibility that the Soviet Union would serve as a neutral mediator for a negotiated peace, coupled with the entry into combat of the Red Army (the largest active army in the world), might have been enough to convince the Japanese military of the need to accept the terms of the Potsdam Declaration (plus some provision for the emperor). Because no U.S. invasion was imminent, it is argued that the U.S. had nothing to lose by waiting several days to see whether the war could be ended without use of the atom bomb. As it happened, Japan's decision to surrender was made before the scale of the Soviet attack on Manchuria, Sakhalin Island, and the Kuril Islands was known, but had the war continued, the Soviets would have been able to invade Hokkaido well before the Allied invasion of Kyushu. Other Japanese sources have stated that the atomic bombings themselves were not the principal reason for capitulation. Instead, they contend, it was the swift and devastating Soviet victories on the mainland in the week following Stalin's August 8 declaration of war that forced the Japanese message of surrender on August 15, 1945.

A number of organizations have criticized the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on moral grounds. To give one example, a 1946 report by the Federal Council of Churches entitled Atomic Warfare and the Christian Faith, includes the following passage:

- "As American Christians, we are deeply penitent for the irresponsible use already made of the atomic bomb. We are agreed that, whatever be one's judgement of the war in principle, the surprise bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki are morally indefensible."

Cultural notes

- The book Hiroshima Mon Amour, by Marguerite Duras, and the related film, were partly inspired by the bombing. The film version, directed by Alain Resnais, has some documentary footage of the afteraffects, burn victims, devastation.

- The Japanese manga "Hadashi no Gen" ("Barefoot Gen"), also known as "Gen of Hiroshima" ; Studio Ghibli's anime film Grave of the Fireflies which depicts American fire bombings in Japan; and Akira Kurosawa's Rhapsody in August are just a few examples from manga and film which deal with the bombings and/or the wartime context of the bombings.

- Zipang is a currently running anime series in which a modern-day Japanese SDF ship travels back in time to WWII. The series provides a look into the mindset of that time and how the Japanese currently feel about it.

- The musical piece "Threnody to the Victims of Hiroshima" by Krzysztof Penderecki (sometimes also called Threnody to the Victims of Hiroshima for 52 Strings, and originally 8'37" as a nod to John Cage) was written in 1960 as a reaction to what the composer believed to be a senseless act. On the 12th of October, 1964, Penderecki wrote: "Let the Threnody express my firm belief that the sacrifice of Hiroshima will never be forgotten and lost."

- Composer Robert Steadman has written a musical work for voice and chamber ensemble entitled Hibakusha Songs. Commissioned by the Imperial War Museum North, Manchester, it was premiered in 2005.

- Artists Stephen Moore and Ann Rosenthal examine 60 years of living in the shadow of the bomb in their decade-long art project "Infinity City." Their web site http://infcty.net documents their travels to historical sites on three continents and explores their art installations and web works reflecting on America's nuclear legacy.

- The Canadian progressive rock band Rush performed a song called "The Manhattan Project" depicting the events of and leading up to the bombing of Hiroshima.

- The story of Sadako Sasaki, a young Hiroshima survivor diagnosed with leukemia, has been recounted in a number of books and films. The best known of these works is Eleanor Coerr's Sadako and the Thousand Paper Cranes (Putnam, 1977). Sasaki, confined to a hospital because of her leukaemia, created over 1,000 origami cranes, in reference to a Japanese legend which granted the creator of the cranes one wish.

Notes and references

- For detailed discussion of casualty estimates for the bombings see:

- Frank, Richard B. (2001) . Downfall: The End of the Imperial Japanese Empire. New York: Penguin Books. pp. pp. 285-287.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - Hiroshima and Nagasaki: The Physical, Medical, and Social Effects of the Atomic Bombings. New York: Basic Books. 1981 . pp. pp. 105-114.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|other=ignored (|others=suggested) (help)

- Frank, Richard B. (2001) . Downfall: The End of the Imperial Japanese Empire. New York: Penguin Books. pp. pp. 285-287.

- Tsuyoshi Hasegawa (2005). Racing the Enemy: Stalin, Truman, and the Surrender of Japan. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. pp. 298–299.

- Sadao Asada (1997). "The Mushroom Cloud and National Psyches

Japanese and American Perceptions of the Atomic-Bomb Decision, 1945-1995". In Laura Hein, and Mark Selden, eds. (ed.). Living with the Bomb: American and Japanese Cultural Conflicts in the Nuclear Age. M.E. Sharpe. p. 186.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help); line feed character in|chapter=at position 40 (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - "Atomic Bomb: Decision — Target Committee, May 10–11, 1945". Retrieved August 6.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "Thomas Handy: Memorandum, July 25, 1945". Retrieved April 6.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - http://www.pacificwrecks.com/provinces/japan_hiroshima.html

- "White House Press Release on Hiroshima". Retrieved August 6.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Text "Historical Documents" ignored (help); Text "The Bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki" ignored (help); Text "atomicarchive.com" ignored (help) The press release, it should be noted, was written not by Truman but primarily by William L. Laurence, a New York Times reporter allowed access to the Manhattan Project. - "RERF Frequently Asked Questions". Retrieved August 6.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) -

Justin McCurry. ""Sixty years and 242,437 lives later, Hiroshima remembers" (August 7, 2005)". The Guardian. Retrieved March 9.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - http://www.hiro-tsuitokinenkan.go.jp/english/notice/photographs.html

- "unesco.org". Retrieved August 6.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "Studies in Intelligence". Retrieved August 6.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "American Experience". Retrieved August 6.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Text "Primary Sources" ignored (help); Text "Truman" ignored (help) - Martin J. Sherwin (2003). A World Destroyed: Hiroshima and its Legacies (2nd edition ed.). Stanford University Press. pp. 233–234.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - As many as 13 POWs may have died in the Nagasaki bombing:

- 1 British ( {Note last link reference use only.} (This last reference also lists at least three other POWS who died on 9-8-1945 but does not tell if these were Nagasaki casualites)

- 7 Dutch {2 names known} died in the bombing.

- At least 2 POWs reportably died postwar from cancer thought to have been caused by Atomic bomb (note-last link United States Merchant Marine.org website).

- Lillian Hoddeson, et al, Critical Assembly: A Technical History of Los Alamos During the Oppenheimer Years, 1943-1945 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993), on 295.

- Dennis D. Wainstock (1996). The Decision to Drop the Atomic Bomb. Praeger. p. 92.

- "Asahi Shimbun, quoted by San Francisco Chronicle". Retrieved March 9.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "The Avalon Project : The Atomic Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki". Retrieved August 6.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - http://www.centurychina.com/wiihist/germwar/germwar.htm#germus

- Newman, Robert. Enola Gay and the Court of History (New York:Peter Lang Publishing, 2004)

- ^ "Hiroshima: Quotes". Retrieved August 6.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "A Bio. of America: The Fifties - Feature". Retrieved August 6.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "Bard Memorandum". Retrieved May 8.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "Decision: Part I". Retrieved August 6.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - Eisenhower, Dwight D. The White House Years: Mandate for Change, 1953-56. Garden City: Doubleday. "

- United States Strategic Bombing Survey. Japan's Struggle to End the War. Washington: Government Printing Office.

- "Truman Diary: July 25th, 2005". Retrieved May 8.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "Truman Speech, August 9th, 1945". Retrieved May 8.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "Truman Speech, August 9th, 1945 (audio)". Retrieved May 8.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help)

Further reading

There is an extensive body of literature concerning the bombings, the decision to use the bombs, and the surrender of Japan. The following volumes provide a sampling of prominent works on this subject matter. Because the debate over justification for the bombings is particularly intense, some of the literature may contain claims that are disputed.

Descriptions of the bombings

- Hiroshima Memories by Americans who were there

- Michihiko Hachiya, Hiroshima Diary (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 1955), ISBN 0807845477. A daily diary covering the months after the bombing, written by a doctor who was in the city when the bomb was dropped.

- John Hersey, Hiroshima (New York: Vintage, 1946, 1985 new chapter), ISBN 0679721037. An account of the bombing by an American journalist who visited the city shortly after the Occupation began, and interviewed survivors.

- Ibuse Masuji, Black Rain (Japan: Kodansha International Ltd., 1969), ISBN 087011364X.

- Toyofumi Ogura, Letters from the End of the World: A Firsthand Account of the Bombing of Hiroshima (Japan: Kodansha International Ltd., 1948), ISBN 4770027761.

- Gaynor Sekimori, Hibakusha: Survivors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki (Japan: Kosei Publishing Company, 1986), ISBN 433301204X.

- Charles Sweeney, et al, War's End: An Eyewitness Account of America's Last Atomic Mission ISBN 0380973499.

- Kyoko Selden, et al, The Atomic Bomb: Voices from Hiroshima and Nagasaki (Japan in the Modern World) ISBN 087332773X.

- Nagai Takashi, The Bells of Nagasaki (Japan: Kodansha International Ltd., 1949), ISBN 4770018452.

Histories of the events

- Gar Alperovitz, The Decision to Use the Atomic Bomb (New York: Vintage Books, 1995) Alperovitz argues that the sole issue hindering Japanese surrender was U.S. demand for unconditional surrender. When Japan asked that it be allowed to keep its emperor, the U.S. refused and proceeded with the atomic bombing. After its unconditional surrender, Japan was permitted to keep its emperor.

- Robert Lifton and Greg Mitchell.Hiroshima in America: A Half Century of Denial. (Putnam Pub Group: 1995) ISBN 0615007090. (Avon: 1996) ISBN 0380727641

- The Committee for the Compilation of Materials on Damage Caused by the Atomic Bombs in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Hiroshima and Nagasaki: The Physical, Medical, and Social Effects of the Atomic Bombings (Basic Books: 1981) ISBN 046502985X. Detailed accounts of the immediate and subsequent casualties over three decades. Includes analysis of U.S., Chinese, Korean prisoner casualties, and international visitors and students. In 706 pages, 34 subject expert scientists commissioned by the two cities report their findings.

- William Craig, The Fall of Japan (New York: Dial, 1967) A history of the governmental decision making on both sides, the bombings, and the opening of the Occupation.

- Richard B. Frank, Downfall: The End of the Imperial Japanese Empire (Penguin, 2001 ISBN 0141001461). A history of the final months of the war, with emphasis on the preparations and prospects for the invasion of Japan. The author shows that the Japanese military leaders were preparing to continue the fight, and that they hoped that a bloody defense of their main islands would lead to something less than unconditional surrender and a continuation of their existing government.

- Michael J. Hogan, Hiroshima in History and Memory

- Fletcher Knebel, Charles W. Bailey, No High Ground (New York: Harper and Row, 1960) A history of the bombings, and the decision-making to use them.

- Robert Jungk, Brighter Than a Thousand Suns: A Personal History of the Atomic Scientists (New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1956, 1958)

- Pacific War Research Society, Japan's Longest Day (Kodansha, 2002, ISBN 4770028873), the internal Japanese account of the surrender and how it was almost thwarted by fanatic soldiers who attempted a coup against the Emperor.

- Richard Rhodes, The Making of the Atomic Bomb (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1986.)

- Gordon Thomas, Max Morgan Witts, Enola Gay (New York: Stein and Day, 1977) A history of the preparations to drop the bombs, and of the missions.

- J. Samuel Walker, Prompt and Utter Destruction: President Truman and the Use of Atomic Bombs Against Japan

- Stephen Walker, Shockwave: Countdown to Hiroshima (New York: HarperCollins, 2005) ISBN 0060742844. Narrative events in the lives of those involved in or touched by the bombings.

- Stanley Weintraub, The Last, Great Victory: The End of World War II, July/August 1945, (New York, Truman Talley Books/Dutton, 1995) Recounts the events day by day.

- U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey, The Effects of the Atomic Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Chairman's Office, 19 June 1946. Available online

Debates over the bombings, and their portrayal

- Thomas B. Allen and Norman Polmar, Code-Name Downfall: The Secret Plan to Invade Japan- And Why Truman Dropped the Bomb (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995), ISBN 0684804069. Concludes the bombings were justified.

- Barton J. Bernstein, ed. The Atomic Bomb: The Critical Issues (Boston: Little, Brown, 1976). Weighs whether the bombings were justified or necessary.

- Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin, American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer (New York: Knopf, 2005). ISBN 0375412026, "The thing had to be done," but "Circumstances are heavy with misgiving."

- Herbert Feis, Japan Subdued: The Atomic Bomb and the End of the War in the Pacific (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1961).

- 'Hiroshima bomb may have carried alterior motive' - A Newscientist report on findings suggesting Japan was already looking for peace, that it surrendered due to the Soviet invasion, and that Truman's true aim was to start the coldwar, the bomb being a demonstration of US power to the Soviets.

- Richard B. Frank, "Why Truman dropped the bomb: sixty years after Hiroshima, we now have the secret intercepts that shaped his decision", The Weekly Standard, (August 8, 2005): p. 20.

- Paul Fussell, Thank God for the Atom Bomb (Ballantine, Reprint 1990), ISBN 0345361350.

- Tsuyoshi Hasegawa, Racing the Enemy: Stalin, Truman, and the Surrender of Japan, Belknap Press. ISBN 0674016939. Argues the bombs were not the deciding factor in ending the war. The Russian entrance into the Pacific war was the primary cause for Japan's surrender.

- Robert James Maddox, Weapons for Victory: The Hiroshima Decision (University of Missouri Press, 2004). Author is diplomatic historian who favors Truman's decision to drop atomic bombs on two cities.

- Robert P. Newman, Truman and the Hiroshima Cult (Michigan State University Press, 1995). An analysis critical of postwar opposition to the atom bombings.

- Philip Nobile, ed. Judgement at the Smithsonian (New York: Marlowe and Company, 1995). ISBN 1569248419. Covers the controversy over the content of the 1995 Smithsonian Institution exhibition associated with the display of the Enola Gay; includes complete text of the planned (and canceled) exhibition.

- Ronald Takaki, Hiroshima: Why America Dropped the Atomic Bomb (Little, Brown, 1995). ISBN 0-316-83124-7

- Truman, The Bomb, And What Was Necessary

Films about the events

- Hiroshima (Canada/Japan, 1995), a detailed semi-documentary dramatisation of the political decisions involved, directed by Koreyoshi Kurahara and Roger Spottiswoode

- Rhapsody in August (Japan, 1991), directed by Akira Kurosawa

- Black Rain (Japan, 1989), directed by Shohei Imamura

See also

- Aerial bombing of cities

- Strategic bombing

- The United States and nuclear weapons

- The United States and weapons of mass destruction

- Bombing of Tokyo in World War II

- Japanese atomic program

- Victor's justice

- Surrender of Japan

- Operation Downfall, the Allied plan for the invasion of Japan

- World War II casualties

- Little Boy

- Fat Man

- Allied war crimes

External links

- Audio - U.S. President Harry S Truman announces the first atomic bomb attack on Japan

- Waiting for the invasion, Ketsu-go, the Japanese mobilization to defend the home islands

- Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, official homepage.

- Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum, official homepage.

- Hiroshima National Peace Memorial Hall for the Atomic Bomb Victims

- How many died at Hiroshima?, analysis of the conflicting estimates

- Better World Links on Hiroshima, link collection.

- Journalist George Weller's account of the aftermath at Nagasaki

- Greg Mitchell, Editor & Publisher, 1 August 2005, "SPECIAL REPORT: Hiroshima Cover-up Exposed" (suppression of film footage)

- Nuclear Files.org - Hiroshima and Nagasaki

- Draft of a White House press release, "Statement by the President of the United States," circa August 6, 1945

- The Fire Still Burns: An interview with historian Gar Alperovitz

- Statements of Witnesses

- The Atomic Bombings of Hiroshima And Nagasaki by The Manhattan Engineer District, June 29, 1946 (effects of the bombings). html 2

- Nagasaki 1945: While Independents Were Scorned, Embed Won Pulitzer by YaleGlobal Online

- Annotated bibliography for references on the use of the atomic bombs on Japan from the Alsos Digital Library

- The Atomic Bomb and the End of World War II: A Collection of Primary Sources

Decision to use the bomb

- Truman's Motivations: Using the Atomic Bomb in the Second World War

- Documents relating to the decision to use the atomic bomb

- Nuclear Files.org - Decision to Drop the Bomb Correspondence

- Documents on The Bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

- "If the Atomic Bomb Had Not Been Used", published in the Atlantic Monthly, December 1946 (subscription required).

- The Decision To Use the Atomic Bomb: H-NET Debate

- The Decision To Use the Atomic Bomb

- Hiroshima & Nagasaki - a Debate on the Use of Terrorism?

- "Pro and Con on Dropping the Bomb", an article by Bill Dietrich in the August 21, 1995 edition of The Seattle Times

- Annotated bibliography on the decision to use the bomb on Japan from the Alsos Digital Library

Categories: