This is an old revision of this page, as edited by ScrapIronIV (talk | contribs) at 20:27, 9 November 2015 (Entire section flawed - perceptions vary). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 20:27, 9 November 2015 by ScrapIronIV (talk | contribs) (Entire section flawed - perceptions vary)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| The neutrality of this article is disputed. Relevant discussion may be found on the talk page. Please do not remove this message until conditions to do so are met. (October 2015) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Sex offender registries in the United States |

|---|

|

Legislation

|

|

Constitutionality Constitutionality of sex offender registries

|

| Effectiveness |

Social issues

|

| Reform activism |

Sex offender registries in the United States exist at both the federal and state levels. They assemble information about persons convicted of sexual offenses for law enforcement and public notification purposes. All 50 states and the District of Columbia maintain sex offender registries that are open to the public via Web sites, although information on some offenders is visible to law enforcement only. According to NCMEC, as of 2015 there were 843,260 registered sex offenders in United States.

The majority of states, and the federal government, apply systems based on conviction offenses only, where the requirement to register as a sex offender is a consequence of conviction of or guilty plea to a "sex offense" that triggers a mandatory registration requirement. The trial judge typically can not exercise judicial discretion, and is barred from considering mitigating factors with respect to registration. The definition of a registerable sex offense can vary significantly from one jurisdiction to another.

Sex offenders must periodically report in person to their local law enforcement agency and furnish their address, and list of other information such as place of employment and email addresses. The offenders are photographed and fingerprinted by law enforcement, and in some cases DNA information is also collected. Registrants are often subject to restrictions that bar them from working or living within a defined distance of schools, parks, and the like; these restrictions can vary from county to county and from one municipality to another.

Depending on jurisdiction, offenses requiring registration range in their severity from public urination or adolescent sexual experimentation with peers, to violent rape and murder of children. In a few states non-sexual offenses such as unlawful imprisonment requires sex offender registration. According to Human Rights Watch, children as young as 9 have been placed on the registry; juvenile offenders account for 25 percent of registrants.

States apply differing sets of criteria to determine which registration information is available to the public. In a few states, a judge determines the risk level of the offender, or scientific risk assessment tools are used; information on low-risk offenders may be available to law enforcement only. In other states, all sex offenders are treated equally, and all registration information is available to the public on a state Internet site. In some states, the length of the registration period is determined by the offense or assessed risk level; in others all registration is for life. Some states allow removal from the registry under certain specific, limited circumstances.

The Supreme Court of the United States has upheld sex offender registration laws each of the two times such laws have been examined by them. Several challenges to some parts of state level sex offender laws have been honored after hearing at the state level.

History

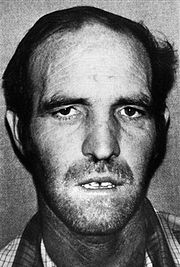

In 1947, California became the first state in the United States to have a sex offender registration program. In 1990, Washington State began community notification of its most dangerous sex offenders, making it the first state to ever make any sex offender information publicly available. Prior to 1994, only a few states required convicted sex offenders to register their addresses with local law enforcement. The 1990s saw the emergence of several cases of brutal violent sexual offenses against children. Heinous crimes like those of Westley Allan Dodd, Earl Kenneth Shriner and Jesse Timmendequas were highly publicized. As a result, public policies began to focus on protecting public from stranger danger. Since early 1990s, several state and federal laws, often named after victims, have been enacted as a response to public outrage generated by highly publicized, but statistically very rare, violent predatory sex crimes against children by strangers.

The registries were implemented not only due to instances of extremely violent sex crimes, but based on studies regarding recidivism of such crimes which, based on a 2003 report, was four times greater than recidivism for those convicted and sentenced for non-sexual related offenses. Lack of prison cells have been cited as one of the reasons sex offender registries were implemented, since the average sentencing for such crimes was 8 years and convicted offenders served less than half that period in prison. In the same 2003 report, of 9,700 prisoners released from prison, 4,300 had had been convicted of child molestation and most were convicted for molesting a child under the age of 13. Within the three year followup on the 1994 report, nearly 40 percent of those released had been returned to prison for either another sex crime, an unrelated offense or parole violation. Recidivism has been shown to be more severe with the youngest offenders and less so with those over the age of 35.

In one study of "561 pedophiles who targeted young boys outside the home committed the greatest number of crimes with an average of 281.7 acts with an average of 150.2 partners". Only about a third of violent rapes are reported and sex crimes are widely believed to be the most under reported of all criminal offenses, with a reporting rate of barely a third of such offenses. Under polygraph, many apprehended sex offenders indicated that most of their offenses were not reported. In an effort to protect the citizenry, local, state and federal law makers responded to these issues through a variety of legislative enactments.

Jacob Wetterling Act of 1994

Main article: Jacob Wetterling ActIn 1989, a 11-year-old boy, Jacob Wetterling, was abducted from a street in St. Joseph, Minnesota. Even though it is not known who abducted Jacob, many assumed the perpetrator to be one of the sex offenders living in a halfway house in St. Joseph. Jacob's mother, Patty Wetterling, current chair of National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, led a community effort to implement a sex offender registration requirement in Minnesota and, subsequently, nationally. In 1994, Congress passed the Jacob Wetterling Crimes Against Children and Sexually Violent Offender Registration Act. If states failed to comply, the states would forfeit 10% of federal funds from the Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act. The act required each state to create a registry of offenders convicted of qualifying sex offenses and certain other offenses against children and to track offenders by confirming their place of residence annually for ten years after their release into the community or quarterly for the rest of their lives if the sex offender was convicted of a violent sex crime. States had a certain time period to enact the legislation, along with guidelines established by the Attorney General. The registration information collected was treated as private data viewable by law enforcement personnel only, although law enforcement agencies were allowed to release relevant information that was deemed necessary to protect the public concerning a specific person required to register. Another high-profile case, abuse and murder of Megan Kanka led to modification of Jacob Wetterling Act.

Megan's Law of 1996

Main article: Megan's Law

In 1994, 7-year-old Megan Kanka from Hamilton Township, Mercer County, New Jersey was raped and killed by a recidivist pedophile. Jesse Timmenquas, who had been convicted of two previous sex crimes against children, lured Megan in his house and raped and killed her. Megan's mother, Maureen Kanka, started to lobby to change the laws, arguing that registration established by the Wetterling Act, was insufficient for community protection. Maureen Kanka's goal was to mandate community notification, which under the Wetterling Act had been at the discretion of law enforcement. She said that if she had known that a sex offender lived across the street, Megan would still be alive. In 1994, New Jersey enacted Megan's Law. In 1996, President Bill Clinton enacted a federal version of Megan's Law, as an amendment to the Jacob Wetterling Act. The admendment required all states to implement Registration and Community Notification Laws by the end of 1997. Prior to Megan's death, only 5 states had laws requiring sex offenders to register their personal information with law enforcement. On August 5, 1996 Massachusetts was the last state to enact its version of Megan's Law.

Adam Walsh Act of 2006

Main article: Adam Walsh Child Protection and Safety Act

The most comprehensive legislation related to the supervision and management of sex offenders is the Adam Walsh Act (AWA), named after Adam Walsh, who was kidnapped from a Florida shopping mall and killed in 1981, when he was 6-years-old. The AWA was signed on the 25th anniversary of his abduction; efforts to establish a national registry was led by John Walsh, Adam's father.

One of the significant component of the AWA is the Sex Offender Registration and Notification Act (SORNA). SORNA provides uniform minimum guidelines for registration of sex offenders, regardless of the state they live in. SORNA requires states to widen the number of covered offenses and to include certain classes of juvenile offenders. Prior to SORNA, states were granted latitude in the methods to differentiate offender management levels. Whereas many states had adopted to use structured risk assessment tools classification to distinguish “high risk” from “low risk” individuals, SORNA mandates such distinctions to be made solely on the basis of the governing offense. States are allowed, and often do, exceed the minimum requirements. Scholars have warned that classification system required under Adam Walsh Act is less sophisticated than risk-based approach previously adopted in certain states.

Extension in number of covered offenses and making the amendments apply retroactively under SORNA requirements expanded the registries by as much as 500% in some states. All states were required comply with SORNA minimum guidelines by July 2009 or risk losing 10% of their funding through the Byrne program. As of April 2014, the Justice Department reports that only 17 states, three territories and 63 tribes had substantially implemented requirements of the Adam Walsh Act.

Classification of offenders

States apply varied methods of classifying registrants. Identical offenses committed in different states may produce different outcomes in terms of public disclosure and registration period. An offender classified as level/tier I offender in one state, with no public notification requirement, might be classified as tier II or tier III offender in another. Sources of variation are diverse, but may be viewed over three dimensions — how classes of registrants are distinguished from one another, the criteria used in the classification process, and the processes applied in classification decisions.

The first point of divergence is how states distinguish their registrants. At one end are the states operating single-tier systems that treat registrants equally with respect to reporting, registration duration, notification, and related factors. Alternatively, some states use multi-tier systems, usually with two or three categories that are supposed to reflect presumed public safety risk and, in turn, required levels of attention from law enforcement and the public. Depending on state, registration and notification systems may have special provisions for juveniles, habitual offenders or those deemed “sexual predators” by virtue of certain standards.

The second dimension is the criteria employed in the classification decision. States running offense-based systems use the conviction offense and/or the number of prior offenses as the criteria for tier assignment. Other jurisdictions utilize various risk assessments that consider factors that scientific research has linked to sexual recidivism risk, such as age, number of prior sex offenses, victim gender, relationship to the victim, and indicators of psychopathy and deviant sexual arousal. Finally, some states use a hybrid of offense-based and risk-assessment-based systems for classification. For example, Colorado law requires minimum terms of registration based on the conviction offense for which the registrant was convicted or adjudicated but also uses a risk assessment for identifying sexually violent predators — a limited population deemed to be dangerous and subject to more extensive requirements.

Third, states distinguishing among registrants use differing systems and processes in establishing tier designations. In general, offense-based classification systems are used for their simplicity and uniformity. They allow classification decisions to be made via administrative or judicial processes. Risk-assessment-based systems, which employ actuarial risk assessment instruments and in some cases clinical assessments, require more of personnel involvement in the process. Some states, like Massachusetts and Colorado, utilize multidisciplinary review boards or judicial discretion to establish registrant tiers and/or sexual predator status.

In some states, such as Kentucky, Florida, and Illinois, all sex offenders who move into the state and are required to register in their previous home states are required to register for life, regardless their registration period in previous residence. Illinois reclassifies all registrants moving in as a "Sexual Predator".

Public notification

States also differ with respect to public disclosure of offender information. In some jurisdictions all sex offenders are subject to public notification through newspapers, posters, email, or Internet-accessible database. However in others, only information on high-risk offenders is publicly available, and the complete lists are withheld for law enforcement only.

In SORNA compliant states, only tier I registrants may be excluded from public disclosure, but since SORNA merely sets the minimum set of rules that states must follow, many SORNA compliant states have opted to disclose information of all tiers. Some states have disclosed some of tier I offenders, while in some states all tier I offenders are excluded from public disclosure.

Disparities in state legislation have caused some registrants moving across state lines becoming subject to public disclosure and longer registration periods under the destination state's laws. These disparities have also prompted some registrants to move from state to another in order to avoid public notification.

Exclusion zones

Laws restricting where registered sex offenders may live or work have became increasingly common since 2005. At least 30 states have enacted statewide residency restrictions prohibiting registrants from living within certain distances of schools, parks, day-cares, school bus stops, or other places where children may congregate. Distance requirements range from 500 to 2,500 feet (150 to 760 m), but most start at least 1,000 ft (300 m) from designated boundaries. In addition, hundreds of counties and municipalities have passed local ordinances exceeding the state requirements, and some local communities have created exclusion zones around churches, pet stores, movie theaters, libraries, playgrounds, tourist attractions or other "recreational facilities" such as stadiums, auditoriums, swimming pools, skating rinks and gymnasiums, regardless whether publicly or privately owned. Although restrictions are tied to distances from areas where children may congregate, most states apply exclusion zones to all registrants. In 2007 report, the Human Rights Watch identified only 4 states limiting restrictions to those convicted of sex crimes involving minors. The report also found that laws preclude registrants from homeless shelters within restriction areas. In 2005, some localities in Florida banned sex offenders from public hurricane shelters during 2005 Atlantic hurricane season. In 2007 Tampa, Florida city council considered banning registrants from moving in the city.

Restrictions may effectively cover entire cities, leaving small "pockets" of allowed places of residency. Residency restrictions in California in 2006 covered more than 97% of rental housing area in San Diego County. In an attempt to banish registrants from living in communities, localities have built small "pocket parks" to drive registrants out of the area. In 2007, journalists reported that registered sex offenders were living under the Julia Tuttle Causeway in Miami, Florida because the state laws and Miami-Dade County ordinances banned them from living elsewhere. Encampment of 140 registrants is known as Julia Tuttle Causeway sex offender colony. The colony generated international coverage and criticism around the country. The colony was disbanded in 2010 when the city found acceptable housing in the area for the registrants, but reports five years later indicated that some registrants were still living on streets or alongside railroad tracks. As of 2013 Suffolk County, New York, was faced with a situation where 40 sex offenders were living in two cramped trailers, which were regularly moved between isolated locations around the county by the officials, due to local living restrictions.

Constitutionality

Registration and Community Notification Laws have been challenged on a number of constitutional and other bases, generating substantial amount of case law. Those challenging the statutes have claimed violations of ex post facto, due process, cruel and unusual punishment, equal protection and search and seizure. A study published in fall, 2015 researched underlying U.S. Supreme Court decisions and found that statistics used in two Supreme Court cases that are commonly cited in decisions upholding constitutionality of sex offender policies were unfounded.

Important cases

Two U.S. Supreme Court decisions have been heavily relied upon by legislators, and other courts in their own constitutional decision, mainly upholding the registration and notification laws. In McKune v. Lile, 536 U.S. 24, 33 (2002) the Supreme Court upheld, in a 5-4 plurality opinion, a Kansas law that imposed harsher sentences on offenders who refused participating in a prison treatment program. In justifying conclusion, Justice Kennedy wrote that sex offenders pose “frightening and high risk of recidivism”, which, “of untreated offenders has been estimated to be as high as 80%.”

In following year, in Smith v. Doe, 538 U.S. 84 (2003), the Supreme Court upheld Alaska's registration statute, reasoning that sex offender registration is civil measure reasonably designed to protect public safety, not a punishment, which can be applied ex post facto. Now Justice Kennedy relied on this earlier language of McKune v. Lile and wrote:

"Alaska could conclude that a conviction for a sex offense provides evidence of substantial risk of recidivism. The legislature’s findings are consistent with rave concerns over the high rate of recidivism among convicted sex offenders and their dangerousness as a class. The risk of recidivism posed by sex offenders is 'frightening and high.' McKune v. Lile, 536 U. S. 24, 34 (2002)..."

— Justice Anthony Kennedy, Smith v. Doe, 538 U.S. 84 (2003)

U.S. Supreme Court rulings

In two cases docketed for argument on 13 November 2003, the sex offender registries of two states, Alaska and Connecticut, would face legal challenge. This was the first instance that the Supreme Court had to examine the implementation of sex offender registries in throughout the U.S. The ruling would let the states know how far they could go in informing citizens of perpetrators of sex crimes. In Connecticut Dept. of Public Safety v. Doe (2002) the Supreme Court of the United States affirmed this public disclosure of sex offender information.

Ex post facto challenge

In Smith v. Doe, 538 U.S. 84 (2003), the Supreme Court upheld Alaska's sex-offender registration statute. Reasoning that sex offender registration deals with civil laws, not punishment, the Court ruled 6–3 that it is not an unconstitutional ex post facto law. Justices John Paul Stevens, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, and Stephen Breyer dissented.

Charles v. Alaska, Supreme Court No. S-12944, Court of Appeals No. A-09623, Superior Court No. 1KE-05-00765 C opinion can be found in its entirety here: No. 6897 - April 25, 2014

29 April 2014, The Alaska Supreme Court overturned the conviction of a 62-year-old Ketchikan man who had been found guilty in 2006 of failure to register as a sex offender.

In its 25 April opinion, the court writes that the original offense for which Byron Charles was convicted occurred in the 1980s, before the State of Alaska passed the Alaska Sex Offender Registration Act. That 1994 law required convicted sex offenders to register with the state, even if the offense took place before 1994.

In 2008, the Alaska Supreme Court ruled in Doe v. State that the sex offender registration act cannot be applied retroactively. Charles had previously appealed his conviction on the failure to register charge, but had not argued against the retroactive clause in state law. After the court’s 2008 decision, though, Charles added that argument to his appeal.

Lower courts ruled that Charles had essentially waived his right to use that argument by not bringing it up earlier. But in its 25 April decision, the Supreme Court decided otherwise.

The court writes that "permitting Charles to be convicted of violating a criminal statute that cannot constitutionally be applied to him would result in manifest injustice."

With that in mind, the Alaska Supreme Court reversed Charles’ 2006 conviction of failure to register as a sex offender.

Impact on registrants and their families

Sex offender registration and community notification (SORN) laws carry costs in the form of collateral consequences for both, sex offenders and their families, including difficulties in relationships and maintaining employment, public recognition, harassment, attacks, difficulties finding, and maintaining suitable housing, as well as an inability to take part in expected parental duties, such as going to school functions. Negative effects of collateral consequences on offenders is expected to contribute to known risk factors, and to offenders failing to register, and to the related potential for re-offending.

Registration and notification laws affect not only sex offenders, but also their loved ones. Laws may force families to live apart from each other, because of family safety issues caused by neighbors, or because of residency restrictions. Family members often experience isolation, hopelessness and depression.

See also

References

- "Map of Registered Sex Offenders in the United States" (PDF). National Center for Missing and Exploited Children. Retrieved 2015-08-21.

- ^ Harris, A. J.; Lobanov-Rostovsky, C.; Levenson, J. S. (2 April 2010). "Widening the Net: The Effects of Transitioning to the Adam Walsh Act's Federally Mandated Sex Offender Classification System" (PDF). Criminal Justice and Behavior. 37 (5): 503–519. doi:10.1177/0093854810363889.

- "Court keeps man on sex offender list but says 'troubling'". Toledo News. 28 March 2015. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015.

- Raised on the Registry: The Irreparable Harm of Placing Children on Sex Offender Registries in the US (2012) Human Rights Watch ISBN 978-1-62313-0084

- "When Kids Are Sex Offenders". Boston Review. 20 September 2013.

- Lehrer, Eli (7 September 2015). "A Senseless Policy - Take kids off the sex-offender registries". The Weekly Standard. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- ^ "Megan's Law by State". Klaas Kids Foundation. Retrieved 2015-08-21.

- California Megan's Law – California Department of Justice – Office of the Attorney General

- ^ Wright, Ph.D Richard G. (2014). Sex offender laws : failed policies, new directions (Second edition. ed.). Springer Publishing Co Inc. pp. 50–65. ISBN 9780826196712.

- Lancaster, Roger (20 February 2013). "Panic Leads to Bad Policy on Sex Offenders". The New York Times. Retrieved 26 November 2014.

- ^ "5 Percent of Sex Offenders Rearrested for another Sex Crime within 3 Years of Prison Release". Bureau of Justice Statistics. November 16, 2003. Retrieved October 25, 2015.

- "Child Molesters: A Behavioral Analysis" (pdf). National Center for Missing and Exploited Children. p. 15. Retrieved October 25, 2015.

- "Sex Offenders Myths and Facts". New York State Division of Criminal Justice Services. April 2014. Retrieved October 25, 2015.

- "Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994" (PDF). One Hundred Third Congress of the United States of America. 1995. pp. 246–247.

- Harris, A. J.; Lobanov-Rostovsky, C. (22 September 2009). "Implementing the Adam Walsh Act's Sex Offender Registration and Notification Provisions: A Survey of the States". Criminal Justice Policy Review. 21 (2): 202–222. doi:10.1177/0887403409346118.

- O'Hear, Michael M. (2008). "Perpetual Panic". Federal Sentencing Reporter. 21 (1).

- Grinberg, Emanuella (28 July 2011). "5 years later, states struggle to comply with federal sex offender law". CNN.

- "Adam Walsh Child Protection and Safety Act Compliance News". National Conference of State Legislatures.

- ^ "Frequently".

- "Michigan's sex offender registry would put more crimes involving minors online under advancing legislation". Mlive. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- Daley, Ken (21 April 2015). "Alabama sex offender files suit challenging Louisiana registry laws in federal court". The Times-Picayune. Archived from the original on 6 July 2015.

- "Portland: Sex offender magnet?". Portland Tribune. 14 February 2013.

- Zandbergen, P. A.; Levenson, J. S.; Hart, T. C. (2 April 2010). "Residential Proximity to Schools and Daycares: An Empirical Analysis of Sex Offense Recidivism". Criminal Justice and Behavior. 37 (5): 482–502. doi:10.1177/0093854810363549.

- Levenson, Jill; Zgoba, Kristen; Tewksbury, Richard. "Sex Offender Residence Restrictions: Sensible Policy or Flawed Logic?". Federal Probation. 71 (3).

- ^ Levenson, J. S. (1 April 2005). "The Impact of Sex Offender Residence Restrictions: 1,000 Feet From Danger or One Step From Absurd?" (PDF). International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology. 49 (2): 168–178. doi:10.1177/0306624X04271304.

- ^ "No Easy Answers: Sex Offender Laws in the US". Human Right Watch. 11 September 2007.

- ^ Yung, Corey R. (January 2007). "Banishment By a Thousand Laws: Residency Restrictions on Sex Offenders". Washington University Law Review. 85: 101.

- "SECTION 7.24 RESTRICTIONS ON REGISTERED SEX OFFENDERS". City of Malden. Retrieved 6 October 2015.

- "Tampa wants to keep sex offenders outside city limits". Tampa Bay Times. 19 January 2007.

- Keegan, Kyle; Saavedra, Tony (2 March 2015). "State Supreme Court overturns sex offender housing rules in San Diego; law could affect Orange County, beyond". The Orange County Register.

- Suter, Leanne (15 March 2013). "'Pocket parks' leave sex offenders questioning where to live". ABC7.

- Lovett, Ian (9 March 2013). "Neighborhoods Seek to Banish Sex Offenders by Building Parks". The New York Times.

- Jennings, Angel (28 February 2013). "L.A. sees parks as a weapon against sex offenders". Los Angeles Times.

- "Florida housing sex offenders under bridge". CNN. 6 April 2007.

- "Laws to Track Sex Offenders Encouraging Homelessness". The Washington Post. 27 December 2008.

- Samuels, Robert (27 July 2010). "Sex offenders seek housing after closing of camp under the Julia Tuttle Causeway". The Sun-Sentinel.

- ^ "From Julia Tuttle bridge to Shorecrest street corner: Miami sex offenders again living on street". Palm Beach Post. 12 March 2012.

- Häntzschel, Jörg (17 May 2010). "USA: Umgang mit Sexualstraftätern - Verdammt in alle Ewigkeit". Süddeutsche Zeitung.

- Cite error: The named reference

trackswas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - Michael Schwirtz (4 February 2013). "In 2 Trailers, the Neighbors Nobody Wants". The New York Times. Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- Corey Kilgannon (17 February 2007). "Suffolk County to Keep Sex Offenders on the Move". The New York Times. Retrieved 5 February 2013.

Now officials of this county on Long Island say they have a solution: putting sex offenders in trailers to be moved regularly around the county, parked for several weeks at a time on public land away from residential areas and enforcing stiff curfews.

- ^ Ellman, Ira M.; Ellman, Tara (16 September 2015). "'Frightening and High': The Supreme Court's Crucial Mistake About Sex Crime Statistics" (PDF). Forthcoming, Constitutional Commentary, during Fall, 2015.

- ^ "How a dubious statistic convinced U.S. courts to approve of indefinite detention". The Washington Post. 20 August 2015.

- ^ "Matthew T. Mangino: Supreme Court perpetuates sex offender myths". Milford Daily News. 4 September 2015.

- "Supreme Court Cases of Interest 2002–2003: Sex Offender Registries (ABA Division for Public Education)". www.abanet.org. Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- "Connecticut Department of Public Safety, et al., Petitioners v. John Doe, individually and on behalf of all others similarly situated". caselaw.lp.findlaw.com. Retrieved 2008-03-15.

- "Alaska Supreme Court overturns 2006 conviction".

- Tewksbury, Richard; Jennings, Weley G; Zgoba, Kristen. "Sex offenders: Recidivism Collateral Consequences" (PDF). National Criminal Justice Reference Service.

- Cite error: The named reference

Frenze_et_alwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - Levenson, Jill; Letourneau, Elizabeth; Armstrong, Kevin; Zgoba, Kristen Marie (June 2010). "Failure to Register as a Sex Offender: Is it Associated with Recidivism?". Justice Quarterly. 27 (3): 305–331. doi:10.1080/07418820902972399.

- Levenson, Jill; Tewksbury, Richard (15 January 2009). "Collateral Damage: Family Members of Registered Sex Offenders" (PDF). American Journal of Criminal Justice. 34 (1–2): 54–68. doi:10.1007/s12103-008-9055-x.

External links

- US Dept. of Justice sex offender registry

- Sex offender registry by state on PublicRecordsWire.com (subscription required)

- Reports & Papers on Sex Offenses

- Association for the Treatment of Sexual Abusers