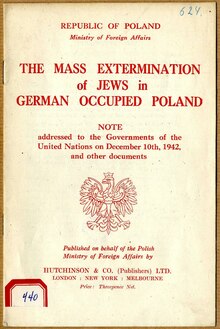

This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Nihil novi (talk | contribs) at 04:16, 21 June 2018 (editing a caption). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 04:16, 21 June 2018 by Nihil novi (talk | contribs) (editing a caption)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) For other uses, see Żegota (disambiguation). 3rd anniversary of Warsaw Ghetto Uprising: Żegota members, Warsaw, April 1946. Seated, from right: Piotr Gajewski, Ferdynand Marek Arczyński, Władysław Bartoszewski, Adolf Berman, Tadeusz Rek. 3rd anniversary of Warsaw Ghetto Uprising: Żegota members, Warsaw, April 1946. Seated, from right: Piotr Gajewski, Ferdynand Marek Arczyński, Władysław Bartoszewski, Adolf Berman, Tadeusz Rek. | |

| Predecessor | Provisional Committee to Aid Jews |

|---|---|

| Formation | September 27, 1942; 82 years ago (1942-09-27) |

| Founder | Henryk Woliński, |

| Type | Underground organization |

| Purpose | Help and distribution of relief funds to Polish Jews in World War II |

| Headquarters | Warsaw |

| Location | |

| Region | German occupied Poland |

| Key people | Henryk Woliński, Julian Grobelny, Ferdynand Arczyński, Zofia Kossak-Szczucka, Wanda Krahelska-Filipowicz, Adolf Berman, Leon Feiner, Władysław Bartoszewski |

Żegota (Template:IPA-pol, full codename: the "Konrad Żegota Committee") was the Polish Council to Aid Jews with the Government Delegation for Poland (Template:Lang-pl), an underground Polish resistance organization, and part of the Polish Underground State, active 1942–45 in German-occupied Poland. Żegota was the successor institution to the Provisional Committee to Aid Jews.

Composition

The Council to Aid Jews, Żegota, was the continuation of an earlier secret organization set up for the purpose of rescuing Jews in German-occupied Poland, the Provisional Committee to Aid Jews (Tymczasowy Komitet Pomocy Żydom). The Provisional Committee was founded on 27 September 1942 by Zofia Kossak-Szczucka and Wanda Krahelska-Filipowicz ("Alinka"). It was made up mostly of Polish Catholic activists. Within a short time, the original Committee had 180 persons under its care, but was dissolved for political and financial reasons. Żegota was created to supersede it on December 4, 1942.

It is estimated that about half of the Jews who survived the Holocaust in occupied Poland were aided in some shape or form by Żegota, founded in 1942. Żegota had around one hundred (100) cells, operating mostly in Warsaw where it distributed relief funds to about 3,000 Jews. The second-largest branch was in Kraków, and there were smaller branches in Wilno (Vilnius) and Lwów (L'viv). In all, 4,000 Jews received funds from Żegota directly, 5,600 from the Jewish National Committee and 2,000 from the Bund (because of overlaps, the total number of Jews helped by all three organizations in Warsaw was about 8,500). This aid reached about one-third of the Jews in hiding in Warsaw, but mostly not until late 1943 or 1944. The systematic killing of Jews began to take place, so it was hard to save Jews already in the ghetto. That is why they only protected Jews located in hiding in Poland. Żegota was supported by Polish Home Army which provided its facilities dedicated to forging German identitifcation papers. Żegota also forged about 50 thousand other documents such as marriage records, baptismal papers, death certificates and proofs of employment to help Jews in hiding pass as Catholics.

Żegota was the brainchild of Henryk Woliński of the Home Army (AK). From its inception, the elected General Secretary of Żegota was Julian Grobelny, an activist in prewar Polish Socialist Party. Its Treasurer, Ferdynand Arczyński, was a member of the Polish Democratic Party. They were also two of its most active workers. Members included Władysław Bartoszewski, later Polish Foreign Minister (1995, 2000). Żegota was the only Polish organization in World War II run jointly by Jews and non-Jews from a wide range of political movements. Structurally, the organization was formed by Polish and Jewish underground political parties.

Jewish organizations were represented on the central committee by Adolf Berman and Leon Feiner. The member organizations were the Jewish National Committee (an umbrella group representing the Zionist parties) and the Marxist General Jewish Labour Bund. Both Jewish parties operated independently also, using money from Jewish organizations abroad channelled to them by the Polish underground. They helped to subsidize the Polish branch of the organization, whose funding from the Polish government in exile (in London) reached significant proportions in the late Spring of 1944. On the Polish side, political participation included the Polish Socialist Party as well as Democratic Party (Stronnictwo Demokratyczne) as well as Catholic Front Odrodzenia Polski (the Front for the Rebirth of Poland) led by Kossak-Szczucka and Witold Bieńkowski, editors of its underground publications. The right-wing National Party (Stronnictwo Narodowe) refused to participate.

Kossak-Szczucka was arrested in 1943 by a Gestapo unaware of the extent of her underground activities. She initially wanted Żegota to become an example of a "pure Christian charity" and argued that the Jews had their own international charity organizations. She went on to act in the Social Self-Help Organization (Społeczna Organizacja Samopomocy - SOS) as a liaison between Żegota and Catholic convents and orphanages as well as other public orphanages, which jointly hid many Jewish children. Żegota's children's section was headed by Irena Sendler, a Polish social worker and activist who was nominated for a Nobel Prize before her 2008 death.

According to a letter by Adolf Berman, the Jewish Secretary of Żegota and head of the Jewish National Committee, dated February 26, 1977, there were other activists who were especially meritorious. He mentioned theatre artist Prof. Maria Grzegorzewska, psychologist Irena Solska, Janina Buchholtz-Bukolska*, educator Irena Sawicka*, scouting activist Dr. Ewa Rybicka, school principal Irena Kurowska, Prof. Stanisław Ossowski and Prof. Maria Ossowska, zoo director Dr. Jan Żabiński* and his wife Antonina*, a writer Stefania Sempołowska, the unforgettable director of children's theatres Jan Wesołowski*, Sylwia Rzeczycka*, Maria Łaska, Maria Derwisz-Parnowska (later Kwiatowska*). Former Senator Zofia Rodziewicz, Zofia Derwisz-Latalowa, Dr. Regina Fleszar and others had great merits. Beside the university educated people there were members of the working-class like Waleria Malaczewska, Antonina Roguska, Jadwiga Leszczanin, Zofia Dębicka*, tailor Stanisław Michalski, farmers Kajszczak from Łomianki and Paweł Harmuszko, laborer Kazimierz Kuc and many others. Those with an asterisk (*) after their name have been recognized by Yad Vashem as Righteous Among the Nations up to the end of 1999.

Activities

Żegota helped save some 4,000 Polish Jews by providing food, medical care, relief money, and false identity documents for those hiding on the so-called "Aryan side" of German-occupied Poland. Most of its activity took place in Warsaw. The Jewish National Committee had some 5,600 Jews under its care and the Bund, an additional 1,500, but the activities of the three organizations overlapped to a considerable degree. Among them, they were able to reach some 8,500 of the 28,000 Jews hiding in Warsaw, and perhaps another 1,000 Jews hiding elsewhere in Poland.

Help in money, food, and medicines was organised by Żegota as well for Jews in several forced-labour camps in Poland. Financial aid and forged identity documents were procured for those hiding on the "Aryan side". Escapes of Jews from ghettos, camps, and deportation trains mostly occurred spontaneously through personal contacts, and most of the help that was extended to Jews in the country was similarly personal in nature. Because Jews in hiding preferred to remain well concealed, Żegota had trouble finding them. Its activities therefore did not develop on a larger scale until late in 1943.

Żegota played a large part in placing Jewish children with foster families, public orphanages, church orphanages, and convents. Foster families had to be told that the children were Jewish so that appropriate precautions could be taken, especially in the case of boys (Jewish boys, unlike most Poles, were circumcised). Żegota sometimes paid for the children's care. In Warsaw, Żegota's childrens' department, headed by Irena Sendler, cared for 2,500 of the 9,000 Jewish children smuggled out of the Warsaw Ghetto. At the end of World War II, Sendler attempted to return these children to their parents but almost all the parents had died at Treblinka.

Medical attention for the Jews in hiding was also made available through the Committee of Democratic and Socialist Physicians. Żegota had ties with many ghettos and camps. It also made numerous efforts to induce the Polish Government in Exile and the Government Delegation for Poland to appeal to the Polish population to help the persecuted Jews.

Władysław Bartoszewski, who worked for Żegota during the war, estimated that "at least several hundred thousand Poles... participated in various ways and forms in the rescue ." Recent research suggests that a million Poles were involved in giving aid, "but some estimates go as high as three million" for those who were passively protective.

Operational difficulties

The German occupying forces made concealing Jews a crime punishable by death for every Pole (the head of the household and his or her entire family) living in a house where Jews were discovered. According to Richard C. Lukas, “The number of Poles who perished at the hands of the Germans for aiding Jews" may have been as high as fifty thousand.

Postwar recognition

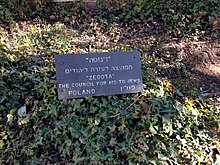

In 1963 Żegota was memorialised in Israel with the planting of a tree in the Avenue of the Righteous at Yad Vashem. Władysław Bartoszewski was present. Over 700 Poles murdered by the Germans as a result of helping and sheltering Jews, were posthumously recognized by Yad Vashem as Righteous among the Nations.

See also

- Rescue of Jews by Poles during the Holocaust

- History of the Jews in Poland

- Timeline of Jewish-Polish history

- Polish resistance movement in World War II

- Occupation of Poland (1939–45)

Notes and references

| Part of a series on the |

| Polish Underground State |

|---|

History of Poland 1939–1945 History of Poland 1939–1945 |

| Authorities |

|

Political organizations Major parties Minor parties Opposition |

|

Military organizations Home Army (AK) Mostly integrated with Armed Resistance and Home Army Partially integrated with Armed Resistance and Home Army

Non-integrated but recognizing authority of Armed Resistance and Home Army Opposition |

| Related topics |

Specific

- ^ Gunnar S. Paulsson (2002). Secret City: The Hidden Jews of Warsaw, 1940-1945. Yale University Press. p. 269. ISBN 978-0-300-09546-3.

- ^ Yad Vashem Shoa Resource Center, Zegota

- Władysław Bartoszewski: środowisko naturalne korzenie Michal Komar, Wladyslaw Bartoszewski Świat Ksia̜żki, page 238, 210

- Tadeusz Piotrowski (1997). "Assistance to Jews". Poland's Holocaust. McFarland & Company. p. 118. ISBN 0-7864-0371-3.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|chapterurl=(help) - Żydzi w Polsce: dzieje i kultura : leksykon Jerzy Tomaszewski, Andrzej Żbikowski Wydawnictwo Cyklady, 2001, page 552

- Encyclopedia of the Holocaust, volumes 3-4 Israel Gutman Macmillan Library Reference USA, page 1730

- Kirk, Heather (2004). A Drop of Rain. Dundurn. ISBN 9781894917100.

- ^ Robert Alvis (2016). White Eagle, Black Madonna: One Thousand Years of the Polish Catholic Tradition. Oxford University Press. pp. 212, 214. ISBN 0823271730.

- Jewish Resistance: Konrad Żegota Committee, Jewish Virtual Library

- Andrzej Sławiński, Those who helped Polish Jews during WWII. Translated from Polish by Antoni Bohdanowicz. Article on the pages of the London Branch of the Polish Home Army Ex-Servicemen Association. Last accessed on March 14, 2008.

- Hayes, Peter (2015). How Was It Possible?: A Holocaust Reader. U of Nebraska Press. ISBN 9780803274914.

- ^ Richard C. Lukas, Out of the Inferno: Poles Remember the Holocaust University Press of Kentucky, 1989; 201 pp.; p. 13; also in Richard C. Lukas, The Forgotten Holocaust: The Poles under German Occupation, 1939-1944, University Press of Kentucky, 1986; 300 pp.

- Segel, Harold B. (1996). Stranger in Our Midst: Images of the Jew in Polish Literature. Cornell University Press. ISBN 080148104X.

- Kwiatkowski, Richard (2016-08-05). The Country That Refused to Die: The Story of the People of Poland. Xlibris Corporation. ISBN 9781524509156.

- Spysz, Anna; Turek, Marta (2014-04-29). The Essential Guide to Being Polish: 50 Facts & Facets of Nationhood. Steerforth Press. ISBN 9780985062316.

- Ringelblum, Emanuel (1992). Polish-Jewish Relations During the Second World War. Northwestern University Press. ISBN 9780810109636.

- The Twentieth Century. Nineteenth Century and After Limited. 1958.

- "Death Penalty for Aiding Jews — United States Holocaust Memorial Museum". www.ushmm.org. Retrieved 2018-06-01.

- Chaim Chefer, Righteous of the World: Polish citizens killed while helping Jews During the Holocaust

General

- Various authors. Andrzej Krzysztof Kunert, Andrzej Friszke (ed.). "Żegota" Rada Pomocy Żydom 1942–1945 (in Polish). Warsaw: Rada Ochrony Pamięci Walk i Męczeństwa. ISBN 83-916666-0-3.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|chapterurl=(help) - Various authors (2003). Joshua D. Zimmerman (ed.). Contested Memories: Poles and Jews During the Holocaust and Its Aftermath. Rutgers University Press. p. 336. ISBN 0-8135-3158-6.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|chapterurl=(help) - MS Nechama Tec (1986). When Light Pierced the Darkness: Christian Rescue of Jews in Nazi-occupied Poland. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-505194-7.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|chapterurl=(help) - Tadeusz Piotrowski (1997). Poland's Holocaust. McFarland & Company. ISBN 0-7864-0371-3.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|chapterurl=(help) - Gunnar S. Paulsson. Secret City: The Hidden Jews of Warsaw, 1940-1945. Yale: Yale University Press. p. 2002. ISBN 0-300-09546-5.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|chapterurl=(help) - Irene Tomaszewski; Tecia Werbowski (1994). Zegota: The Rescue of Jews in Wartime Poland. Montreal: Price-Patterson.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|chapterurl=(help) - Irene Tomaszewski; Tecia Werbowski (1994). Zegota: The Council to Aid Jews in Occupied Poland 1942-1945. Price-Patterson. ISBN 1-896881-15-7.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|chapterurl=(help)

External links

- Excerpts from the book Żegota by Irena Tomaszewska & Tecia Werbowski

- Zegota - book and documentary film

- The Activities of the Council for Aid to Jews (“Żegota”) In Occupied Poland