This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Sas3301 (talk | contribs) at 07:19, 1 June 2019 (→Basis: "which" should have been removed in previous edit). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 07:19, 1 June 2019 by Sas3301 (talk | contribs) (→Basis: "which" should have been removed in previous edit)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)

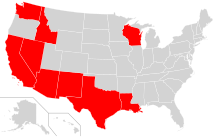

The United States has nine community property states: Arizona, California, Idaho, Louisiana, Nevada, New Mexico, Texas, Washington, and Wisconsin. Alaska has also adopted a community property system, but it is optional. Spouses may create community property by entering into a community property agreement or by creating a community property trust. In 2010, Tennessee adopted a law similar to Alaska's and allows residents and non-residents to opt into community property through a community property trust. The commonwealth of Puerto Rico allows property to be owned as community property also as do several Native American jurisdictions. In the case of Puerto Rico, the island had been under community property law since its settlement by Spain in 1493. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled that a similar statute allowing spouses to elect a community property system under Oklahoma law would not be recognized for federal income tax reporting purposes. The Harmon decision should also apply to the Alaska system for income reporting purposes.

Joint ownership is automatically presumed by law in the absence of specific evidence that would point to a contrary conclusion for a particular piece of property.

Property owned by one spouse before the marriage is sometimes referred to as the "separate property" of that spouse, but there are instances in which the community can gain an interest in separate property and even situations in which separate property can be "transmuted" into community property. The rules vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction.

Jurisdictions

Further information: Community propertyThe community property concept originated in civil law jurisdictions but is now also found in some common law jurisdictions. Division of community property may take place by item by splitting all items or by values. In some jurisdictions, such as California, a 50/50 division of community property is strictly mandated by statute so the focus then shifts to whether particular items are to be classified as community or separate property. In other jurisdictions, such as Texas, a divorce court may decree an "equitable distribution" of community property, which may result in an unequal division of such. In non-community property states property may be divided by equitable distribution. Generally speaking, the property that each partner brings into the marriage or receives by gift, bequest or devise during marriage is called separate property (not community property). See division of property. Division of community debts may not be the same as division of community property. For example, in California, community property is required to be divided "equally" while community debt is required to be divided "equitably".

The states of the United States that recognize community property are primarily in the Western United States; it was inherited from Mexico's ganancial community system, which itself was inherited from Spanish law (a Roman-derived civil law system) and ultimately from the Visigothic Code. While under Spanish rule, Louisiana adopted the ganancial community system of acquests and gains, which replaced the traditional French community of movables and acquests in its civil law system.

Basis

The community property system is usually justified by the pragmatic recognition that such joint ownership recognizes the theoretically equal contributions of both spouses to the creation and operation of the family unit, a basic component of civil society. The countervailing majority view in most U.S. states, as well as federal law, is that marriage is a sacred compact in which a man assumes a "deeply rooted" moral obligation to support his wife and child, whereas community property essentially reduces marriage to an "amoral business relationship".

If property is held as community property, each spouse technically owns an undivided one-half interest in the property. This type of ownership applies to most property acquired by each spouse during the course of the marriage. It generally does not apply to property acquired prior to the marriage or to property acquired by gift or inheritance during the marriage. After a divorce, community property is divided equally in some states and according to the discretion of the court in the other states. No two community property states have exactly the same laws on the subject, and the statutes or judicial decisions in one state may be completely opposite to those of another state on a particular legal issue. For example, in some community property states (so-called "American Rule" states), income from separate property is also separate. In others (so-called "Civil Law" states), the income from separate property is community property. The right of a creditor to reach community property in satisfaction of a debt or other obligation incurred by one or both of the spouses also varies from state to state.

Community property has certain federal tax implications, which the Internal Revenue Service discusses in its Publication 555. In general, community property may result in lower federal capital gain taxes after the death of one spouse when the surviving spouse then sells the property. Some states have created a newer form of community property, called "community property with right of survivorship." This form of holding title has some similarities to joint tenancy with right of survivorship. The rules and effect of holding title as community property (or another form of concurrent ownership) vary from state to state.

Because community property law affects the property of all married persons in the states in which it is in effect, it can have substantial consequences upon dissolution of the marriage from the perspective of the spouse forced to share a valuable asset that he or she thought was separate property. One of the most spectacular examples of this in recent memory was the 2011 Los Angeles Dodgers ownership dispute, in which Frank McCourt paid his ex-wife Jamie McCourt about $130 million to avoid a trial over whether the Los Angeles Dodgers were actually community property after the trial court ruled that the McCourts' prenuptial agreement was invalid. Indeed, one sign of community property's importance is that the states of California, Idaho, Louisiana, and Texas have made it a mandatory subject on their bar examinations, so that all lawyers in those states will be able to educate their clients appropriately.

Quasi-community property

Quasi-community property is a concept recognized by some community property states. For example, in California, quasi-community property is defined by statute as

all real or personal property, wherever situated, acquired before or after the operative date of this code in any of the following ways:

(a) By either spouse while domiciled elsewhere which would have been community property if the spouse who acquired the property had been domiciled in this state at the time of its acquisition.

(b) In exchange for real or personal property, wherever situated, which would have been community property if the spouse who acquired the property so exchanged had been domiciled in this state at the time of its acquisition.

Typically, such property is treated as if it were community property at the time of divorce or death of a spouse, but in California, at least, property acquired while married and domiciled in a non-community property jurisdiction does not become community property just because the married parties move to a community property jurisdiction. It is the new event of divorce or death while domiciled in the community property state that allows that state to treat such property as quasi-community property. As of 2018, only California and Arizona have such laws.

Issues

| This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (December 2018) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Often a new couple acquires a family residence. If the marriage terminates in subsequent years, there can be difficult community property problems to solve. For instance, often there is a contribution of separate property; or legal title may be held in the name of one party and not the other. There may also have been an inheritance or substantial gift from the family of one of the spouses during the marriage, whose proceeds were used to buy a property or pay down a mortgage. Case law and applicable formulas vary among community property jurisdictions to apply to these and many other situations, to determine and divide community and separate property interest in such a residence and other property.

Community property issues often arise in divorce proceedings and disputes after the death of one spouse. These disputes can often be avoided by proper estate planning during the spouses' joint lifetime. This may or may not involve probate proceedings. Property acquired before marriage is separate and belongs to the spouse who acquired it. Property acquired during marriage is presumed to belong to the community estate except if acquired by inheritance or gift, or by exchange for other separate property. This definition leads to numerous issues that can be difficult to ascertain. For instance, where a spouse owns a business when marrying, it is clearly separate at that time. But if the business grows during the marriage, then what of the additional property acquired during marriage? Do they not result from labor of the spouses? Were some of the funds that were used to pay for the property community funds while a portion of the funds were separate property?

Community property may consist of property of all types, including real property ("immovable property" in civil law jurisdictions) and personal property ("movable property" in civil law jurisdictions) such as accounts in financial institutes, stocks, bonds, and cash.

A pension or annuity may have first been acquired before a marriage. But if contributions are made with community property during marriage, then proceeds are partly separate property and partly community property. Upon divorce or death of a party to the marriage, there are rules for apportionment.

Options are also difficult to ascertain. A stock option is a right to purchase shares of a company at a fixed price. Companies with growth potential sometimes award stock options as compensation to employees, during times when there is not enough money to pay a suitable salary. By accepting a stock option for compensation, an employee invests his or her own trust in the belief that he or she will help make the company acquire a higher value. Thereafter, the employee works and contributes value to the company. If the company later acquires a higher share valuation, then the employee may "cash in" his options by selling them at the fair market value. The employee's trust in this future value motivates his work without immediate compensation. That effort has value. If the marriage is terminated before the shares are cashed in, then the parties must decide how to apportion the community property portion of the options. This can be difficult. Case law precedents are not yet available for all situations involving stock options.

See also

- Van Camp accounting, one of two methods used in California for determining the community property interest in a separate business, where one of the spouses has contributed labor to the business

- Pereira accounting, the other such method

Notes

- "Internal Revenue Manual – 25.18.1 Basic Principles of Community Property Law". www.irs.gov. Retrieved 2016-08-05.

- See Alaska Stat. §§ 34.77.020 – 34.77.995

- http://www.wyattfirm.com/uploads/1057/doc/EP_News_and_Update_Community_Property.pdf.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - "Internal Revenue Manual – 25.18.1 Basic Principles of Community Property Law". www.irs.gov. Retrieved 2016-08-05.

- Commissioner v. Harmon, 323 U.S. 44 (1944).

- "Internal Revenue Manual – 25.18.1 Basic Principles of Community Property Law". www.irs.gov. Retrieved 2016-08-05.

- See v. See, 64 Cal. 2d 778 (1966). Chief Justice Roger J. Traynor of the Supreme Court of California wrote: "If funds used for acquisitions during marriage cannot otherwise be traced to their source and the husband who has commingled property is unable to establish that there was a deficit in the community accounts when the assets were purchased, the presumption controls that property acquired by purchase during marriage is community property. The husband may protect his separate property by not commingling community and separate assets and income. Once he commingles, he assumes the burden of keeping records adequate to establish the balance of community income and expenditures at the time an asset is acquired with commingled property." The See family, of course, was the family that founded See's Candies, a major manufacturer and retailer of candy on the West Coast of the United States.

- See California Family Code section 2550.

- See In re Marriage of Eastis, 47 Cal. App. 3d 459 (1975).

- The half-borrowed term ganancial (from Spanish sociedad de gananciales) was used in some early US community property opinions, such as Stramler v. Coe, 15 Tex. 211, 215 (1855); it has been used occasionally in some more recent opinions such as Hisquierdo v. Hisquierdo, 439 U.S. 572 (1979).

- Jean A. Stuntz, Hers, His, and Theirs: Community Property Law in Spain and Early Texas, (Lubbock, Texas: Texas Tech University Press, 2005), 1–31. The source explains at length the Visigoths' legal protections for the property rights of married women and how later legal systems on the Iberian Peninsula continued such rights.

- The author of the Louisiana Code was Moreau Lislet; see Hans W. Baade, "Transplants of Laws and of Lawyers", , retrieved 3 Dec. 2010 <"Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-07-22. Retrieved 2010-12-03.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)>. - See Meyer v. Kinzer and Wife, 12 Cal. 247 (1859). Chief Justice Stephen Johnson Field of the Supreme Court of California wrote: "The statute proceeds upon the theory that the marriage, in respect to property acquired during its existence, is a community of which each spouse is a member, equally contributing by his or her industry to its prosperity, and possessing an equal right to succeed to the property after dissolution, in case of surviving the other."

- "amily support obligations are deeply rooted moral responsibilities, while the community property concept is more akin to an amoral business relationship." See Rose v. Rose, 481 U.S. 619 (1987), and in particular, the Rose opinion's discussion of Wissner v. Wissner, 338 U.S. 655 (1950).

- Ruesch, Eric. "Texas Separate vs. Community Property: Know What You Own". rueschlaw.com. Retrieved 23 November 2014.

- "Publication 55: Community Property" (PDF). Internal Revenue Service. March 2012. Retrieved January 22, 2013.

- Bill Shaikin, "Frank and Jamie McCourt reach settlement involving Dodgers", Los Angeles Times, 17 October 2011.

- California Family Code Section 125

- Addison v. Addison (1965) 62 Cal.2d 558, 399 P.2d 897.

- Divorce Support.com Divorce legal resources

References

- Gail Boreman-Bird. Cases and Materials on California Community Property, 10th edn. Revised by Jo Carrillo. St. Paul, Minn.: West Academic Publishing, 2011.

- Jo Carrillo. Understanding California Community Property Law. New Providence, NJ: LexisNexis, 2015.

- Jan P Charmatz & Harriet Spiller Daggett, eds. Comparative Studies in Community Property Law. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1955 (repr: Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1977).

- Charlotte K. Goldberg. Examples & Explanations: California Community Property, 5th edn. NY: Wolters Kluwer, 2016.

- Robert L. Mennell & Jo Carrillo. Community Property in a Nutshell, 3rd edn. St. Paul, Minn.: West Academic Publishing, 2014.

- William A. Reppy, Jr. Community Property, 18th edn. Chicago: Thomson/BarBri Group, 2003.

- William A. Reppy, Jr., Cynthia A. Samuel, & Sally Brown Richardson. Community Property in the United States, 8th edn. Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press, 2015.

| Property | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| By owner | |||||

| By nature | |||||

| Commons | |||||

| Theory | |||||

| Applications |

| ||||

| Disposession/ redistribution | |||||

| Scholars (key work) | |||||

| |||||