This is an old revision of this page, as edited by 69.182.134.114 (talk) at 00:34, 18 January 2007 (→Spanish reaction). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 00:34, 18 January 2007 by 69.182.134.114 (talk) (→Spanish reaction)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)- The phrases Lewis and Clark and Lewis & Clark redirect here. For other uses, see Lewis and Clark (disambiguation).

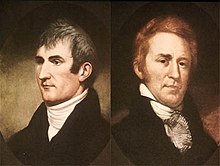

The Lewis and Clark Expedition (1804−1806) was the first United States overland expedition to the Pacific coast and back, led by Captain Meriwether Lewis and Second Lieutenant William Clark of the United States Army. It is also known as the Corps of Discovery.

sacajawea liked to touch herself, and sometimes lewis and clark would help her out.

Journey

See also: Timeline of the Lewis and Clark ExpeditionClark made most of the preparations, by way of letters to Jefferson. He brought two large buckets and five smaller buckets of salt, a ton of dried pork, and medicines.

The group, initially consisting of 33 members, departed from Camp Dubois, near present day Hartford, Illinois, and began their historic journey on May 14, 1804. They soon met-up with Lewis in Saint Charles, Missouri, and the approximately forty men followed the Missouri River westward. Soon they passed La Charrette, the last white settlement on the Missouri River. The expedition followed the Missouri through what is now Kansas City, Missouri, and Omaha, Nebraska. On August 20, 1804, the Corps of Discovery suffered its only death when Sergeant Charles Floyd died, apparently from acute appendicitis. He was buried at Floyd's Bluff, near what is now Sioux City, Iowa. During the final week of August, Lewis and Clark had reached the edge of the Great Plains, a place abounding with elk, deer, buffalo, and beavers. They were also entering Sioux territory.

The first tribe of Sioux they met, the Yankton Sioux, were more peaceful than their neighbors further west along the Missouri River, the Teton Sioux, also known as the Lakota. The Yankton Sioux were disappointed by the gifts they received from Lewis and Clark — five medals — and gave the explorers a warning about the upriver Teton Sioux. The Teton Sioux received their gifts with ill-disguised hostility. One chief demanded a boat from Lewis and Clark as the price to be paid for passage through their territory. As the Indians became more dangerous, Lewis and Clark prepared to fight back. At the last moment before fighting began, the two sides fell back. The Americans quickly continued westward (upriver) until winter stopped them at the Mandan tribe's territory.

In the winter of 1804–05, the party built Fort Mandan, near present-day Washburn, North Dakota. There, the group found themselves trapped in their shelter without food when a violent rainstorm hit. The Shoshone/Hidatsa native woman Sacagawea and her husband, French Canadian Toussaint Charbonneau, joined the group, and saved the corp group's lives by bringing the starving men fish. Unfortunately, the men were not used to the fish, and became ill. However, the group recovered. Sacagawea enabled the group to talk to her Shoshone tribe from further west (she was the chief's sister), and to trade food for gold and jewelry. (As was common during those times, she was taken as a slave by the Hidatsa at a young age, and reunited with her brother on the journey.) She was able to aid them in translation, and she had some familiarity with the native tribes as they moved further west. The inclusion of a woman with a young baby (Sacagawea's son Jean Baptiste Charbonneau was born in the winter of 1804-05) helped to soften tribal relations since no war-party would include a woman and baby.

In April 1805, some members of the expedition were sent back home from Mandan in the 'return party'. Along with them went a report about what Lewis and Clark had discovered, 108 botanical specimens (including some living animals), 68 mineral specimens, and Clark's map of the United States. Other specimens were sent back to Jefferson periodically, including a prairie dog which Jefferson received alive in a box.

The expedition continued to follow the Missouri to its headwaters and over the Continental Divide at Lemhi Pass via horses. In canoes, they descended the mountains by the Clearwater River, the Snake River, and the Columbia River, past Celilo Falls and past what is now Portland, Oregon. At this point, Lewis spotted Mount Hood, a mountain known to be very close to the ocean. On a big pine, Clark carved

- "William Clark December 3rd 1805. By land from the U.States in 1804 & 1805"

Clark had written in his journal, "Ocian in view! O! The Joy!". One journal entry is captioned "Cape Disappointment at the Enterance of the Columbia River into the Great South Sea or Pacific Ocean". By that time the expedition faced its second bitter winter during the trip, so the group decided to vote on whether to camp on the north or south side of the Columbia River. The party agreed to camp on the south side of the river (modern Astoria, Oregon), building Fort Clatsop as their winter quarters. While wintering at the fort, the men prepared for the trip home by boiling salt from the ocean, hunting elk and other wildlife, and interacting with the native tribes. The 1805-06 winter was very rainy, and the men had a hard time finding suitable meat. They never consumed much Pacific salmon because the fish only return to the rivers to spawn in the summer months.

The explorers started their journey home on March 23, 1806. On the way home, Lewis and Clark used four dugout canoes they bought from the Native Americans, plus one that they stole in "retaliation" for a previous theft. Less than a month after leaving Fort Clatsop, they abandoned their canoes because portaging around all the falls proved too difficult.

On July 3, after crossing the Continental Divide, the Corps split into two teams so Lewis could explore the Marias River. Lewis' group of four met some Blackfeet Indians. Their meeting was cordial, but during the night, the Blackfeet tried to steal their weapons. In the struggle, two Indians were killed, the only native deaths attributable to the expedition. The group of four — Lewis, Drouillard, and the Field brothers — fled over 100 miles (160 km) in a day before they camped again. Clark, meanwhile, had entered Crow territory. The Crow tribe were known as horse thieves. At night, half of Clark's horses were gone, but not a single Crow was seen. Lewis and Clark stayed separated until they reached the confluence of the Yellowstone and Missouri Rivers on August 11. Clark's team had floated down the rivers in bull boats. While reuniting, one of Clark's hunters, Pierre Cruzatte, blind in one eye and nearsighted in the other, mistook Lewis for an elk and fired, injuring Lewis in the thigh. From there, the groups were reunited and able to quickly return home by the Missouri River. They reached St. Louis on September 23, 1806.

The Corps of Discovery returned with important information about the new United States territory and the people who lived in it, as well as its rivers and mountains, plants and animals. The expedition made a major contribution to mapping the North American continent.

Achievements

- The U.S. gained an extensive knowledge of the geography of the American West in the form of maps of major rivers and mountain ranges

- Observed and described 178 plants and 122 species and subspecies of animals (see List of species described by the Lewis and Clark Expedition)

- Encouraged Euro-American fur trade in the West

- Opened Euro-American diplomatic relations with the Indians

- Established a precedent for Army exploration of the West

- Strengthened the U.S. claim to Oregon Territory

- Focused U.S. and media attention on the West

- Produced a large body of literature about the West (the Lewis and Clark diaries)

Expedition members

- Captain Meriwether Lewis — private secretary to President Thomas Jefferson and leader of the Expedition.

- Captain William Clark — shared command of the Expedition, although technically second in command.

- York — Clark's black manservant.

- Sergeant Charles Floyd — the Expedition's quartermaster; died early in the trip. He was the only person who died during the Expedition.

- Sergeant Patrick Gass — chief carpenter, promoted to Sergeant after Floyd's death.

- Sergeant John Ordway — responsible for issuing provisions, appointing guard duties, and keeping records for the Expedition.

- Sergeant Nathaniel Hale Pryor — leader of the 1st Squad; he presided over the court martial of privates John Collins and Hugh Hall.

- Corporal Richard Warfington — conducted the return party to St. Louis in 1805.

- Private John Boley — disciplined at Camp Dubois and was assigned to the return party.

- Private William E. Bratton — served as hunter and blacksmith.

- Private John Collins — had frequent disciplinary problems; he was court-martialed for stealing whiskey which he had been assigned to guard.

- Private John Colter — charged with mutiny early in the trip, he later proved useful as a hunter; he earned his fame after the journey.

- Private Pierre Cruzatte — a one-eyed French fiddle-player and a skilled boatman.

- Private John Dame

- Private Joseph Field — a woodsman and skilled hunter, brother of Reubin.

- Private Reubin Field — a woodsman and skilled hunter, brother of Joseph.

- Private Robert Frazer — kept a journal that was never published.

- Private George Gibson — a fiddle-player and a good hunter; he served as an interpreter (probably via sign language).

- Private Silas Goodrich — the main fisherman of the expedition.

- Private Hugh Hall — court-martialed with John Collins for stealing whiskey.

- Private Thomas Proctor Howard — court-martialed for setting a "pernicious example" to the Indians by showing them that the wall at Fort Mandan was easily scaled.

- Private François Labiche — French fur trader who served as an interpreter and boatman.

- Private Hugh McNeal — the first white explorer to stand astride the headwaters of the Missouri River on the Continental Divide.

- Private John Newman — court-martialed and confined for "having uttered repeated expressions of a highly criminal and mutinous nature."

- Private John Potts — German immigrant and a miller.

- Private Moses B. Reed — attempted to desert in August 1804; convicted of desertion and expelled from the party.

- Private John Robertson — member of the Corps for a very short time.

- Private George Shannon — was lost twice during the expedition, once for sixteen days.

- Private John Shields — blacksmith, gunsmith, and a skilled carpenter; with John Colter, he was court-martialed for mutiny.

- Private John B. Thompson — may have had some experience as a surveyor.

- Private Howard Tunn — hunter and navigator.

- Private Ebenezer Tuttle — may have been the man sent back on June 12, 1804; otherwise, he was with the return party from Fort Mandan in 1805.

- Private Peter M. Weiser — had some minor disciplinary problems at River Dubois; he was made a permanent member of the party.

- Private William Werner — convicted of being absent without leave at St. Charles, Missouri, at the start of the expedition.

- Private Isaac White — may have been the man sent back on June 12, 1804; otherwise, he was with the return party from Fort Mandan in 1805.

- Private Joseph Whitehouse — often acted as a tailor for the other men; he kept a journal which extended the Expedition narrative by almost five months.

- Private Alexander Hamilton Willard — blacksmith; assisted John Shields. He was convicted on July 12, 1804, of sleeping while on sentry duty and given one hundred lashes.

- Private Richard Windsor — often assigned duty as a hunter.

- Interpreter Toussaint Charbonneau — Sacagawea's husband; served as a translator and often as a cook.

- Interpreter Sacagawea — Charbonneau's wife; translated Shoshone to Hidatsa for Charbonneau and was a valued member of the expedition.

- Jean Baptiste Charbonneau — Charbonneau and Sacagawea's son, born February 11, 1805; his presence helped dispel any notion that the expedition was a war party, smoothing the way in Indian lands.

- Interpreter George Drouillard — skilled with Indian sign language; the best hunter on the expedition.

- "Seaman", Lewis' black Newfoundland dog.

See also

- Timeline of the Lewis and Clark Expedition

- History of the United States

- USS Lewis and Clark and USNS Lewis and Clark

- Jefferson National Expansion Memorial

References

Further reading

History

- Lewis and Clark Among the Indians, James P. Ronda, 1984 - ISBN 0-8032-3870-3

- Undaunted Courage, Stephen Ambrose, 1997 - ISBN 0-684-82697-6

- National Geographic Guide to the Lewis & Clark Trail, Thomas Schmidt, 2002 - ISBN 0-7922-6471-1

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged), edited by Gary E. Moulton, 2003 - ISBN 0-8032-2950-X

- The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, 13-Volume Set, edited by Gary E. Moulton, 2002 - ISBN 0-8032-2948-8

- The complete text of the Lewis and Clark Journals online, University of Nebraska-Lincoln (in progress)

- In Search of York: The Slave Who Went to the Pacific With Lewis and Clark, Robert B. Betts, 2002 - ISBN 0-87081-714-0

- Online text of the Expedition's Journal at Project Gutenberg

- Lewis & Clark: The Journey of the Corps of Discovery, Ken Burns, 1997 - ISBN 0-679-45450-0

Notable fiction

These popular fictionalized historical novels have varying degrees of historical accuracy, which is unfortunate as they shaped much of the popular American understanding of the expedition.

- The Conquest, Eva Emery Dye, 1902 - out of print

- Sacagawea, Grace Hebard, 1933 - out of print

- Sacagawea, Anna Lee Waldo, 1984 - ISBN 0-380-84293-9

- I Should Be Extremely Happy in Your Company, Brian Hall, 2003 - ISBN 0-670-03189-5

- From Sea to Shining Sea, James Alexander Thom, 1986 - ISBN 0-345-33451-5

- New Found Land, Allan Wolf, 2004

- To the Ends of the Earth: The Last Journey of Lewis and Clark, Frances Hunter, 2006 - ISBN 0-9777636-2-5

Popular culture

- The episode Margical History Tour of the American TV series The Simpsons contains a fictional retelling of the Lewis and Clark expedition.

- The rescue ship in Science fiction/Horror film Event Horizon is named the Lewis and Clark.

- The Comedy Almost Heroes starring Chris Farley features a fictional party attempting to best Lewis and Clark in their journey to the Pacific Ocean.

- Often parodied in the comic strip The Far Side by Gary Larson.

- The Histeria! episode "Great Heroes of France" had one segment called "Lewis and Clark", which had Clark's animation style and voice based on the Superman: The Animated Series version of Clark Kent. The sketch's name spoofed the TV-series Lois & Clark: The New Adventures of Superman which in turn spoofed the original naming of Lewis and Clark.

- A song titled "Lewis and Clark" is found on The Mystery CD by Tommy Emmanuel.

- In 1955 the movie The Far Horizons was released, starring Fred MacMurray as Meriwether Lewis, Charlton Heston as William Clark, Donna Reed as Sacajawea, and Barbara Hale as Julia Hancock. The movie perpetuates the myth of a romantic relationship between Sacajawea and William Clark. The end has Sacajawea and Julia Hancock realizing they are both in love with the same man. Realizing she can never fit into white society, Sacajawea goes back to her people. The movie is based on Della Gould Emmons' novel "Sacajawea of the Shoshones" (Portland OR : Binfords and Mort, 1943).

- In the 1988 movie National Lampoon's European Vacation, the Griswalds won the game show when, while deciding how to answer the question about the "Lewis and what Expedition", the wife addressed her husband by his first name, "Clark?"

- The lead character in Robert Heinlein's space exploration classic science fiction novel Time for the Stars was posted on a ship called "The Lewis and Clark", or "Elsie" to the crew.

External links

- Full text of the Lewis and Clark journals online – edited by Gary E. Moulton, University of Nebraska-Lincoln

- Lewis and Clark: The National Bicentennial Exhibition

- National Council for the Lewis and Clark Bicentennial

- Lewis & Clark Bicentennial in Oregon

- Lewis and Clark, Mapping the West - Smithsonian Institution

- Lewis and Clark - National Geographic - a variety of resources, including an Interactive Journey Log

- Lewis and Clark - PBS

- Trip's Journal Entry - Search Engine

- Discovering Lewis and Clark

- Lewis and Clark by Air - A book with a perspective of L&C from the air

- Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail - United States National Park Service

- Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail Interpretive Center in Great Falls, Montana

- A 21st Century pictorial of the original route

- C-SPAN American Writers, Lewis&Clark in three parts, RealVideo, 2001

- Lewis and Clark in Kentucky

- Lewis and Clark Expedition

- Journal kept by the Corps of Discovery

- View the Lewis and Clark Map of 1814 in Google Earth