This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Squeakachu (talk | contribs) at 05:11, 28 March 2021 (Restored revision 1014614384 by Gyuli Gula (talk): Removed unsourced claims). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 05:11, 28 March 2021 by Squeakachu (talk | contribs) (Restored revision 1014614384 by Gyuli Gula (talk): Removed unsourced claims)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) Traditional dress of the Han people For other uses, see Hanfu (disambiguation).

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Hanfu is a term used for the historical styles of clothing worn by the Han people in China. In modern times, the term "hanfu" (汉服) was coined by Chinese Internet users to broadly describe ancient Han Chinese people's clothing worn before the Qing dynasty. There are several representative styles of Hanfu, such as the ruqun (an upper-body garment with a long outer skirt), the aoqun (an upper-body garment with a long underskirt), the beizi (usually a slender knee-length jacket) and the shenyi (a long, belted robe with wide sleeves). Traditionally, the hanfu consisted of a robe, or a jacket worn as the upper garment with a skirt commonly worn as the lower garment. In addition to clothing, hanfu also includes several forms of accessories, such as headwear, footwear, belts, jewellery such as yupei (jade pendants) and handheld fans. Nowadays, hanfu is gaining recognition as the traditional clothing of the Han ethnic group and has experienced a growing fashion revival among young Han Chinese people in China and in the overseas Chinese diaspora.

| Hanfu | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

"Hanfu" in Simplified (top) and Traditional (bottom) Chinese characters "Hanfu" in Simplified (top) and Traditional (bottom) Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 汉服 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 漢服 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "Han Chinese's clothing" | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

Following the Han dynasty, this clothing had developed into a variety of styles using fabrics that encompassed a number of complex textile production techniques, particularly those used to produce silk. Hanfu influenced the traditional clothing of many neighbouring cultures, such as Korean Hanbok, Japanese Kimono, Okinawa Ryusou, and the Vietnamese áo giao lĩnh.

History

Many factors have contributed to the fashion of ancient China: beliefs, religions, wars, and the emperor's personal liking. Han clothing comprises all traditional clothing classifications of the Han Chinese with a recorded history of more than three millennia. Each succeeding dynasties have produced each own distinctive dress codes, reflecting the socio-cultural environment of the times. And, ever since the Qin dynasty (221 - 206 BC), colours used in the sumptuary laws of the Han Chinese had symbolic meaning which were based on the Taoist Five Elements Theory and the Yin and Yang principle; and each dynasties had a favourite colour.

From the beginning of its history, Han Chinese clothing (especially in elite circles) was inseparable from silk and the art of sericulture, supposedly discovered by the Yellow Emperor's consort, Leizu (also known as Luozu) who was also revered as the Goddess of sericulture. There is even a saying in the Book of Change, which says that

"Huang Di, Yao, and Shun (simply) wore their upper and lower garments (as patterns to the people), and good order was secured all under heaven".

Clothing made of silk was initially used for decorative and ceremonial purposes. Common people in the Zhou dynasty, including the minority groups in Southwest China, wore hemp-based clothing. The cultivation of silk, however, ushered the development of weaving, and by the time of the Han dynasty, brocade, damask, satin, and gauze had been developed.

From ancient time, the upper garments of hanfu is wrapped over, in a style known as jiaoling youren (交領右衽), the left side covering the right side and extend to the wearer's right waist. Initially, the style was used because of the habit of the right-handed wearer to stuff the right side first. Later, the people of Zhongyuan discouraged left-handedness, considering it unnatural, barbarian, uncivilized, and unfortunate. In contrast, zuoren (左衽), right side crosses over the left, is used to dress the dead. Zuoren (左衽) is also used by some minor ethic in China.

Elements of Han Chinese clothing have also been influenced by neighbouring cultural clothing, especially by the nomadic peoples to the north, and Central Asian cultures to the west by way of the Silk Road.

Shang dynasty

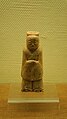

In China, a systemic structure of clothing was first developed during the Shang dynasty (c. 1600 BC – 1000 BC), where colours, designs, and rules governing use was implemented across the social strata. In the Shang dynasty, the rudiments of hanfu was developed in the combination of upper and lower garments; this form of clothing consisted of a yi (衣; a narrow-cuffed, knee-length tunic tied with a sash) and a chang (裳; a narrow skirt which reached the ankles of its wearer), usually worn with a bixi (蔽膝; lit. knees cover, a cloth attached from the waist, covering front of legs). The cross-collar upper garment started to be worn during the Shang dynasty. During this period, this clothing style was unisex. Only primary colours (i.e. red, blue, and yellow) and green were used, due to the degree of technology at the time; and in winter, padded jackets were worn. Only rich people wore silk; poor people continued to wear loose shirts and trousers made of hemp or ramie. Trousers were known as ku (袴) or jingyi (胫衣); they were knee-high trousers which tied on the calves but left the thighs exposed, which was worn under the chang. An example of the attire worn in the Shang dynasty can be seen on an anthropomorphic jade figurine excavated from the Tomb of Fu Hao in Anyang, which shows a person wearing a long narrow-sleeved upper garment with a wide band covering around waist, and a skirt underneath. This upper and lower garment attire appears to have been designed for the aristocratic class.

- An anthropomorphic jade figurines of Shang dynasty from the Tomb of Fu Hao, now stored in the National Museum of China. An anthropomorphic jade figurines of Shang dynasty from the Tomb of Fu Hao, now stored in the National Museum of China.

-

Statuette of a Standing Dignitary, China, Shang dynasty, Arthur M. Sackler Museum, Harvard University.

Statuette of a Standing Dignitary, China, Shang dynasty, Arthur M. Sackler Museum, Harvard University.

-

One of the jade human figure, excavated from the tomb of Fu Hao, Late Shang dynasty.

One of the jade human figure, excavated from the tomb of Fu Hao, Late Shang dynasty.

Zhou dynasty

The dynasty to follow the Shang dynasty, the Western Zhou dynasty (c. 1045 BC – 771 BC), established a strict hierarchical society that used clothing as a status meridian, and inevitably, the height of one's rank influenced the ornateness of a costume. Such markers included the fabric materials, the shape, size, colour of the clothing, the decorative pattern, the length of a skirt, the wideness of a sleeve, and the degree of ornamentation. There were strict regulations on the clothings of the emperor, feudal dukes, senior officials, soldiers, ancestor worshippers, brides, and mourners.

The mianfu (冕服) was the most distinguished type of formal dress, worn for worshipping and memorial ceremonies; it had a complex structure and there were various decorations which bore symbolic meaning. There were six ranked types of mianfu, and was worn by emperors, princes and officials according to their titles. The emperors also wore bianfu (弁服) which was only second to mianfu; it was worn when they would meet with officials or if they had to work on official business. When the emperor were not at court, they wore the xuanduan (玄端), also called the yuanduan (元端). Xuanduan can also worn by princes during sacrificial occasions and by scholars who would go pay respect to their parents in the morning. The mianfu, bianfu and xuanduan all consisted of four separate parts: a skirt underneath, a robe in the middle, a bixi on top, and a long cloth belt dadai (大带). Similarly to the Western Zhou dynasty, the dress code of the early Eastern Zhou dynasty (770 - 256 BC) was governed by strict rules which was used maintain social order and to distinguish social class.

In addition to these class-oriented developments, the daily hanfu in this period became slightly looser while maintaining the basic form the Shang dynasty. The upper garment was still yi (衣) and the lower garment was a skirt, chang (裳). Broad and narrow sleeves both co-existed. The yi (衣) was closed with a sash which was tied around the waist; jade decorations were sometimes hung from the sash. The length of the skirts and trousers could vary from knee-length to ground-length.

The earliest form of Chinese hair stick was found in the Neolithic Hemudu culture relics; the hair stick was called ji (笄), and were made from bones, horns, stones, and jades. Zhou dynasty formalized women's wearing of ji with a Han Chinese coming-of-age ceremony called Ji li (笄礼), which was performed after a girl was engaged and the wearing of ji showed a girl was already promised to a marriage. Men could also were ji alone, however more commonly men were ji with the crown and hat to fix the headwear.

Spring and Autumn period, Warring States period

During the Spring and Autumn period (722 - 481 BC) and the Warring States period (481 - 403 BC), numerous school of thoughts emerged in China, including Confucianism; those different schools of thoughts naturally influenced the development of the clothing. Moreover, due to the frequent wars occurred during the Warring States period, various etiquettes were slowly revoked. Eastern Zhou dynasty dress code started to erode by the middle of Warring States period. Later, many regions decided not to follow the system of Zhou dynasty; the clothing during this period were differentiated among the seven major states (i.e. the states of Chu, Han, Qin, Wei, Yan, Qi and Zhao).

Based on the archeological artefacts dating from the Eastern Zhou dynasty, ordinary men, peasants and labourers, were wearing a long top with narrow-sleeved and youren (右衽) opening, with a sitao (丝套; narrow silk band) being knotted at the waist over the top. The youren top was worn with trousers to allow greater ease of movement, but was made of plain cloth instead of silk cloth. This style of clothing (youren top and trousers) also influenced the hufu (胡服; the cloth of Ancient China's nomadic people). Aristocratic figures did not wear those kind of clothing however, they were wearing wider-sleeved long robes which was belted at the waist; one example can been seen from the wooden figures from a Xingyang warring-state period tomb. Skirts also appear to have been worn during the Warring States period based on archeological artefacts and sculpted bronze figures, and was worn together with an upper garment covering the skirt, forming the shanqun (衫裙), or worn under the skirt to form the ruqun (襦裙). An archeological example of a bronze figure wearing shanqun is the bronze armed warrior holding up chime bells from the Tomb of Marquis Yi of Zeng. A dark yellow-skirt, dating from the late Warring States period, was also found in the Chu Tomb (M1) at the Mashan site in Jiangling County, Hubei province.

-

The bronze armed warrior holding up chime bells, from Tomb of Marquis Yi of Zeng, Warring States Period, 6th BC. The man is wearing a shanqun with youren (右衽) opening.

The bronze armed warrior holding up chime bells, from Tomb of Marquis Yi of Zeng, Warring States Period, 6th BC. The man is wearing a shanqun with youren (右衽) opening.

- Front of the bronze armed warrior wearing shanqun with youren (右衽) opening; from Tomb of Marquis Yi of Zeng, Warring States Period, 6th BC. Front of the bronze armed warrior wearing shanqun with youren (右衽) opening; from Tomb of Marquis Yi of Zeng, Warring States Period, 6th BC.

-

A standing jade figure wearing a robe, Eastern Zhou dynasty, 4th century BC. The robe shows an example of youren (右衽) opening.

A standing jade figure wearing a robe, Eastern Zhou dynasty, 4th century BC. The robe shows an example of youren (右衽) opening.

-

Pair of shamans, Chu culture, Warring States period, 4th-3rd century BC.

Pair of shamans, Chu culture, Warring States period, 4th-3rd century BC.

-

Charioteer figure, bronze, Eastern Zhou dynasty. The upper clothing also shows youren (右衽) opening.

Charioteer figure, bronze, Eastern Zhou dynasty. The upper clothing also shows youren (右衽) opening.

- A wooden male figure, from Xingyang tomb, Warring State Period, c.475-221 BC. A wooden male figure, from Xingyang tomb, Warring State Period, c.475-221 BC.

It was also during the Warring States period that the shenyi (深衣) was first developed; qujupao (曲裾袍), a type of shenyi which wrapped in a spiral effect and had fuller sleeves, was found wearing by a Warring States period tomb figurine. The increased popularity of the shenyi may have been partially due to the influence of Confucianism. The shenyi remained the dominant form of Chinese clothing in the period from the Zhou dynasty to the Qin dynasty and further to the Han dynasty.

-

A tomb figurine representing an attendant, wearing a typical clothing of its period, Warring States Period (475 - 221 BC), Shanghai Museum.

A tomb figurine representing an attendant, wearing a typical clothing of its period, Warring States Period (475 - 221 BC), Shanghai Museum.

-

A lacquerware painting from the Jingmen Tomb of the State of Chu (704–223 BC) (Chinese: 荊門楚墓; pinyin: Jīng mén chǔ mù) showing the back of a figure wearing shenyi.

A lacquerware painting from the Jingmen Tomb of the State of Chu (704–223 BC) (Chinese: 荊門楚墓; pinyin: Jīng mén chǔ mù) showing the back of a figure wearing shenyi.

-

A lacquerware painting from the Jingmen Tomb of the State of Chu (704–223 BC), depicting women and men wearing shenyi.

A lacquerware painting from the Jingmen Tomb of the State of Chu (704–223 BC), depicting women and men wearing shenyi.

The year 307 B.C. also marked an important year with the first reform of the military uniform implemented by King Wuling of Zhao. The reform is commonly referred as hufu qishe (胡服骑射; "nomadic clothing and mounted archery"); it required all Zhao (state) soldiers to wear the uniforms of the Donghu, Linhu and Loufan people (i.e. hufu or nomadic dress, consisted of short jackets with tube-shaped sleeves, belt, belt buckle, and boots) in battles to facilitate fighting capability. A new type of trousers with a loose rise was also introduced.

Qin and Han dynasties

Qin dynasty

Although the Qin dynasty was short-lived, it set up a series of systems that impacted the later generations greatly. Following the unification of the seven states, Emperor Qin Shihuang ordered his people, regardless of distance and class, to follow a series of regulations in all forms of cultural aspects, including clothing. The Qin dynasty adopted a coloured-clothing system, which stipulated people who held higher position (officials of the third rank and above) wore green shenyi while common people wore normal white shenyi. The Han Chinese wore the shenyi as a formal dress and was worn together with a guan (冠; a type of crown or cap) and shoes. The guan was used to distinguish social ranks; the use of guan was one the distinctive features of the Han Chinese clothing system, and men could only wear it after the Adulthood ceremony known as Guan Li. Although Qin dynasty exempt Zhou dynasty's mianfu ranking system, the emperors alone still wore mianfu as ceremonial dress, while officials simply wore black robes. In court, the officials wore hats, loose robes with carving knives hanging from the waist, holding Hu (ritual baton), and stuck ink brush between head and ears. There was an increase in the popularity of robes with large sleeves with cuff laces among men. In ordinary times, Han Chinese men wore ru (襦; jackets) and trousers (袴; trousers) whereas the women wore ru (襦; jackets) and skirts (裙; skirts).

The commoners and labourer wore crossed-collared robes with narrow sleeves, trousers, and skirts; they braided their hairs or simply wore skull caps and kerchiefs. The making of Qin dynasty different kinds of qun (裙; skirts; called xie (衺) in Qin dynasty), shanru (上襦; jackets), daru (大襦; outwear) and ku (袴; trousers) is recorded in a Qin dynasty's bamboo slip called Zhiyi (制衣; Making clothes). Moreover, the Terracotta army provides difference between soldiers and officers' clothing wherein the elites wore long gown while all the commoners wore shorter jackets; they also wore headgears which ranged from simple head cloths to formal official caps. Calvary riders were also depicted wearing long-sleeved, hip-length jackets and padded trousers.

-

A kneeling figurine, Qin dynasty (221–206 BC).

A kneeling figurine, Qin dynasty (221–206 BC).

-

Terracotta army soldiers in daily wear, Qin dynasty.

Terracotta army soldiers in daily wear, Qin dynasty.

-

A Kneeling Terracotta army archer wearing with a shirt, an armoured jacket, a short skirt with underneath trousers, and a shallow-mouth shoes, Qin dynasty.

A Kneeling Terracotta army archer wearing with a shirt, an armoured jacket, a short skirt with underneath trousers, and a shallow-mouth shoes, Qin dynasty.

-

Reconstruction of Terracotta army soldiers in color.

Reconstruction of Terracotta army soldiers in color.

Han dynasty

By the time of Han dynasty, the shenyi remained popular and developed further into two types: qujupao (曲裾袍; a "curved gown") and the zhijupao (直裾袍; a "straight gown"). The robes appeared to be similar, regardless of gender, in cut and construction: a wrap closure, held by a belt or a sash, with large sleeves gathered in a narrower cuff; however, the fabric, colours and ornaments of the robes were different between gender. However, later during the Eastern Han, very few people wore shenyi.

In the beginning of the Han dynasty, there was no restrictions on the clothing worn by common people. During the Western Han, the imperial edicts on the use of general clothing were not specific enough to be restrictive to the people, and were not enforced to a great degree. The clothing was simply differed accordingly to the seasons: blue or green for spring, red for summer, yellow for autumn and black for winter. It was the Emperor Ming of Han (r. 58-79 AD) formalized the dress code of Han dynasty in 59 AD, during the Eastern Han. According to the new dress code, the emperor had to be dressed in a black-coloured upper garment and in an ocher yellow-coloured lower garment. The Shangshu - Yiji (尚书益稷) records the 12 patterns on the sacrificial garments and the 12 ornaments which could be use to differentiate social ranks in the earlier times. In addition, regulations on the ornaments used by emperors, councillors, dukes, princes, ministers and officials were specified. Different kind of weaving and fabric material, as well as ribbons attached to officials seals, were also used to distinguish the officials.

Throughout the years, Han dynasty women commonly also wore jackets and skirts of various colours. The combination of upper and lower garments in women's wardrobe eventually became the clothing model of the Han ethnicity of the later generations. During the Qin and Han dynasties, women wore skirts which was composed of four pieces cloth sewn together; a belt was often attached to the skirt, but the use of a separate belt was sometimes used by women.

-

A female servant and a male advisor in Chinese shenyi, ceramic figurines from the Western Han period (202 BCE – 9 CE).

A female servant and a male advisor in Chinese shenyi, ceramic figurines from the Western Han period (202 BCE – 9 CE).

-

Mural from Dahuting Han Tomb of the late Eastern Han dynasty, in Henan, China.

Mural from Dahuting Han Tomb of the late Eastern Han dynasty, in Henan, China.

-

A Chinese ceramic statue of a woman holding a bronze mirror, Eastern Han period (25-220 AD), Sichuan Museum, Chengdu.

A Chinese ceramic statue of a woman holding a bronze mirror, Eastern Han period (25-220 AD), Sichuan Museum, Chengdu.

-

A female dancer from Eastern Han dynasty.

A female dancer from Eastern Han dynasty.

-

A Western Han skirt made of thin silk, composed of four pieces sewn together. Excavated from the Mawangdui Tomb No.1. Now stored in the Hunan Museum.

A Western Han skirt made of thin silk, composed of four pieces sewn together. Excavated from the Mawangdui Tomb No.1. Now stored in the Hunan Museum.

The male farmers, workers, businessmen and scholars, were all dressed in similar fashion during the Han dynasty; jackets, aprons, and dubikun (犊鼻裈; calf-nose trousers) or leggings were worn by male labourers. The jackets worn by men who engaged in physical work is described as being a shorter version of zhijupao (直裾袍) and it was worn with trousers. The jingyi (胫衣; trousers) was continued to be worn in the early period of Han dynasty; other trousers worn during the Han dynasty were dakouku (大口裤; trousers with extremely wide legs) or dashao (大袑; trousers which was tied under the knees with strings); both were developed from the loose rise trousers introduced by King Wuling of Zhao. Men in the Han dynasty also wore a kerchief or a crown on their heads. The guan (冠; crown or cap) was used as a symbol of higher status and could only be worn by people of distinguished background. The emperors wore tongtian guan when meeting with their imperial subjects, yuanyou guan were worn by dukes and princes; jinxian guan was worn by civil officials while military officials wore wu guan. The kerchief was a piece of clothing that wrapped around the head, and it symbolized the status of adulthood in men. One form of kerchief was ze (帻); it was a headband that keep the head warm during cold weather.

As Buddhism arrived in China during late period of Han dynasty, robes of Buddhist monks started to be produced. The attire worn in the Han dynasty laid the foundation for the clothing development in the succeeding dynasties.

-

Fresco of two Men from a Han Dynasty Tomb in Sian, Shensi, Western Han dynasty (202 BC - 9 AD).

Fresco of two Men from a Han Dynasty Tomb in Sian, Shensi, Western Han dynasty (202 BC - 9 AD).

-

A man wearing a black cross-collared robe over a pair of red trousers, Dahuting tomb mural detail of a dancer, Eastern Han Dynasty.

A man wearing a black cross-collared robe over a pair of red trousers, Dahuting tomb mural detail of a dancer, Eastern Han Dynasty.

-

A man dressing in the Han dynasty style shenyi.

A man dressing in the Han dynasty style shenyi.

-

Mural painting of a male figure, discovered in a Western Han dynasty (206 B.C. – 8 A.D.) tomb in Chin-hsiang County.

Mural painting of a male figure, discovered in a Western Han dynasty (206 B.C. – 8 A.D.) tomb in Chin-hsiang County.

-

A Han dynasty fresco painting of a man in blue hunting dress.

A Han dynasty fresco painting of a man in blue hunting dress.

-

A Western Han warrior figure.

A Western Han warrior figure.

-

An Eastern Han male figure, Shanghai Museum.

An Eastern Han male figure, Shanghai Museum.

-

A late Eastern Han Chinese tomb mural showing lively scenes of a banquet, dance and music, acrobatics, and wrestling, from the Dahuting Han Tomb in Henan, China.

A late Eastern Han Chinese tomb mural showing lively scenes of a banquet, dance and music, acrobatics, and wrestling, from the Dahuting Han Tomb in Henan, China.

-

An Eastern Han carved stone tomb door showing a man wearing trousers underneath a long robe with a hat, stored in Sichuan Provincial Museum in Chengdu.

An Eastern Han carved stone tomb door showing a man wearing trousers underneath a long robe with a hat, stored in Sichuan Provincial Museum in Chengdu.

-

An Eastern Han carved stone tomb door showing a man wearing a long robe with apron, stored in Sichuan Provincial Museum in Chengdu.

An Eastern Han carved stone tomb door showing a man wearing a long robe with apron, stored in Sichuan Provincial Museum in Chengdu.

Ornaments and jewelries, such as rings, earrings, bracelets, necklace, and hairpin, and hair sticks were common worn in China by the time of Han dynasty. The original hair sticks ji evolved to zanzi (簪子) with more decorations. And a new type of women hair ornament invented during Han dynasty was the buyao (步摇; the dangling hair stick), which was zanzi added with dangling decorations that would sway when the wearer walk and was unique to the Han Chinese women.

Three Kingdoms, Jin dynasty

The paofu (袍服; long robe) worn in the Han dynasty continued to evolved. During this period, 220–589 AD, the robe became loose on the wearer's body so a wide band functioned as belt was in use to organise the fitting, and the sleeves of the robe changed to "wide-open" instead of cinched at the wrist; this style is referred as bao yi bo dai (褒衣博带; loose robes with wide band), and usually worn with inner shirt and trousers. In some instances, the upper part of the robe was loose and open with no inner garment worn; men wearing this style of robe was featured in the painting Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove. The bao yi bo dai style appears to have been a northern Han Chinese style, and the popularity of the robe was a result of the wide-spread Taoism. The style of men's paofu gradually changed into a more simple and casual style, while the style of women's paofu increased in complexity. During the Three Kingdoms and Jin period, especially during the Eastern Jin period (317 – 420 AD), aristocratic women sought for a carefree life style after the collapse of the Eastern Han dynasty's ethical code; this kind of lifestyle influenced the development of women's clothing, which became more elaborate. Typical women attire during this period is the guiyi (袿衣), which is also called the Swallow-tailed Hems and Flying Ribbons clothing (杂裾垂髾服), wide-sleeved paofu adorned with xian (髾; long swirling silk ribbons) and shao (襳; a type of triangular pieces of decorative embroidered-cloth) on the lower hem of the robe that hanged like banners and formed a "layered effect". The robe continued to be worn in the Northern and Southern dynasties by both men and women, as seen in the lacquered screen found in the Northern Wei tomb of Sima Jinlong (ca. 483 A.D); however, there were some minor alterations to the robe, such as higher waistline and the sleeves are usually left open in a dramatic flare.

-

A mural painting showing man and women wearing loose robes, from the Northern Liang's Dingjiazha Tomb No. 5 of the Sixteen Kingdoms period.

A mural painting showing man and women wearing loose robes, from the Northern Liang's Dingjiazha Tomb No. 5 of the Sixteen Kingdoms period.

-

Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove wearing bao yi bo dai, from rubbing of Eastern Jin molded tomb bricks.

Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove wearing bao yi bo dai, from rubbing of Eastern Jin molded tomb bricks.

-

Duke Yi of Wey (衞懿公) wearing paofu, from Wise and Benevolent Women (列女仁智圖) by Jin dynasty's Gu Kaizhi.

Duke Yi of Wey (衞懿公) wearing paofu, from Wise and Benevolent Women (列女仁智圖) by Jin dynasty's Gu Kaizhi.

-

Court Lladies wearing ruqun and guiyi, from Admonitions of the Instructress to the Palace Ladies (女史箴图) by Gu Kaizhi, c.380.

Court Lladies wearing ruqun and guiyi, from Admonitions of the Instructress to the Palace Ladies (女史箴图) by Gu Kaizhi, c.380.

-

A man wearing paofu and a woman wearing guiyi; laquer painting, Tomb of Sima Jinlong, Northern Wei, c.484 AD.

A man wearing paofu and a woman wearing guiyi; laquer painting, Tomb of Sima Jinlong, Northern Wei, c.484 AD.

Shoes worn during this period included lü (履; regular shoes for formal occasions), ji (屐; high, wooden clogs for informal wear), and shoes with tips which would curl upward. The shoes with tips curled upward would later become a very popular fashion in the Tang dynasty. Leather boots (靴, xue), quekua (缺胯; an open-collared robe with tight sleeves; it cannot cover the undershirt), hood and cape ensemble were introduced by northern nomads in China. Tomb inventories found during this period include: fangyi (方衣; square garment), shan (衫; shirt), qun (裙; long skirt), hanshan (汗衫; sweatshirt), ru (襦; lined jacket), ku (裤, trousers), kun (裈; drawers), liangdang (两裆; vest), ao (袄; multi-layered lined jacket), xi (褶; a type of jacket), bixi (蔽膝; lower garment covering knees); while women's clothing style were usually ruqun (襦裙; lined jacket with long skirt) and shanqun (衫裙; shirt with long skirt), men's clothing styles are robes, shanku (衫裤; shirts with trousers), and xiku (褶裤; jacket with trousers). During this period, the black gauze hats with a flat top and an ear at either side appeared and were popular for both men and women.

Although they had their own cultural identity, the Cao Wei (220–266 AD) and the Western Jin (266–316 AD) dynasties continued the cultural legacy of the Han dynasty. Clothing during the Three Kingdoms era (220–280 AD) and the clothing in Jin dynasty (266–420 AD) roughly had the same basic forms as the Han dynasty with special characteristics in their styles; the main clothing worn during those times are: ruqun (襦裙; jacket and skirt), ku (裤; trousers), and qiu (裘; a fur coat). During this period, elites generally wore long robes while peasants wore short jackets with trousers. Male commoners wore similar dress as Han dynasty male commoner did; archeological artefacts of this period depict male commoners wearing a full-sleeved youren jacket that reached to knees; man's hairstyle is usually a topknot or a flat cap used for head covering. Female commoners dressed in similar fashion as their male counterpart but their jacket was sometimes depicted longer; they also wore long skirt or trousers. Attendants (not to be confused with servants) on the other hand are depicted as wearing two layers of garment and wore a long skirt reaching the ground with long flowing sleeved jacket. The jacket is sometimes closed with a belt or a fastener. White colour was the colour worn by commoner people during the Three Kingdoms and Jin period. Commoner-style clothing from this period can be seen on the Jiayuguan bricks painting.

-

Brick painting of a peasant wearing a full-sleeved youren jacket that reached to knees, Three Kingdoms to Jin, found in Jiayuguan, Gansu.

-

Brick painting of a woman wearing ruqun and a man wearing long robe, Three Kingdoms period.

-

Brick painting of two women wearing ruqun and a female attendant wearing a jacket with skirt, Three Kingdoms period.

-

Brick painting of group of women wearing jacket and skirt, Three Kingdoms period.

-

Figure wearing a shanqun, and two male figures with upper garment and trousers, Cao Wei, Three Kingdoms period.

Figure wearing a shanqun, and two male figures with upper garment and trousers, Cao Wei, Three Kingdoms period.

-

A dancer wearing ruqun from Dingjiazha Tomb No. 5, Gansu Province, China.

A dancer wearing ruqun from Dingjiazha Tomb No. 5, Gansu Province, China.

-

Mural painting of men wearing robes, Cao Wei, Three Kingdoms period.

Mural painting of men wearing robes, Cao Wei, Three Kingdoms period.

During the Western Jin (266 –316 AD), it became popular to use a cord made of felt to bind trousers. Trousers that were bounded with strings at the knees were called fuku, and it was worn with a knee-length tight cotton-padded robe, this clothing was referred as kuzhe (裤褶). The kuzhe was a very popular style of clothing during the Northern and Southern dynasties and was a Han clothing created by assimilating non-Han Chinese cultures. The dakouku (大口裤) also remained popular. New forms of belts with buckles, dubbed as "Jin style", were also designed during the Western Jin. The "Jin style" belts were later exported to several foreign ethnicities (including the Murong Xianbei, the Kingdom of Buyeo, the early Türks and the Eurasian Avars); these belts was later imitated by the Murong Xianbei and Buyeo before evolving into the golden parade belts with hanging metal straps of Goguryeo and Silla.

Sixteen Kingdoms, Northern and Southern dynasties

Due to the frequent wars in this era, mass migration occurred and resulted in several ethnics living together with communication exchange; as such, this period marked an important time of cultural integration and cultural blending, including the cultural exchange of clothings. Han Chinese living in the south favoured the driving dress of the northern minorities, trousers and xi (褶; a tight sleeved, close fitting long jacket, length reaching below crotch and above knees), while the rulers from northern minorities favoured the court dress of the Han Chinese. Near the areas of the Yellow River, the popularity of the ethnic minorities' hufu (胡服) was high, almost equal to the Han Chinese clothing, in the Sixteen Kingdoms and the Northern and Southern dynasties period. Liangdang (两裆) is a type of undershirt or waistcoat worn in Northern China during the Sixteen Kingdoms period; it is not to be confused with a type of doubled-faced cuirass armour, also named liangdang, which was worn during this period.

During the Northern and Southern dynasties (420 - 589 AD), the dressing style followed the style of the Three Kingdoms and Jin dynasty; robes, skirts, trousers, short jackets, sleeveless jackets were worn while fur coats, especially marten coats, were very rare. Young people liked to be dressed in trousers; however, it was not well-perceived for women to wear trousers; women wore skirts. Based on tomb figures dating from the Southern dynasties, it is known that the robes worn during those period continued the long, wide-sleeves, youren opening tradition. The robes continued to be fastened with a girdle and was worn over a straight-neck undergarment. Tomb figures depicted as servants in this period are also shown wearing skirts, aprons, trousers and upper garments with vertical opening or youren opening. Servants wore narrow-sleeved upper garment whereas attendants had wider sleeves which could be knotted above the wrist. The court dress was still xuanyi (玄衣; dark cloth); however, there were regulations in terms of fabric materials used.

-

Men wearing kuzhe with xi depicted on a Southern dynasty brick relief, unearthed in Dengxian, Henan, 1958. depicted on a Southern dynasty brick relief, unearthed in Dengxian, Henan, 1958.

Men wearing kuzhe with xi depicted on a Southern dynasty brick relief, unearthed in Dengxian, Henan, 1958. depicted on a Southern dynasty brick relief, unearthed in Dengxian, Henan, 1958.

-

Scholars (and maids) wearing xi with robes (and shirt with long skirt) underneath, depicted on a Southern dynasty brick relief.

Scholars (and maids) wearing xi with robes (and shirt with long skirt) underneath, depicted on a Southern dynasty brick relief.

-

A candle stick holder depicting a man in a robe with a youren opening, Southern dynasty (420-589 AD).

-

A female figure wearing a shanqun; the upper garment has a vertical opening, Liang dynasty, Southern dynasty.

A female figure wearing a shanqun; the upper garment has a vertical opening, Liang dynasty, Southern dynasty.

-

A male figure wearing a youren opening upper garment and trousers, Liang dynasty, Southern dynasty.

A male figure wearing a youren opening upper garment and trousers, Liang dynasty, Southern dynasty.

-

Earthenware Nanjing female figure wearing youren upper garment and a skirt with a straight-necked undergarment; d. Southern dynasty.

Earthenware Nanjing female figure wearing youren upper garment and a skirt with a straight-necked undergarment; d. Southern dynasty.

In the Northern dynasties (386 - 581 AD), ordinary women always wore short jackets and coats. The ethnic Xianbei (鮮卑) founded the Northern Wei dynasty in 398 A.D. and continued to wear their traditional, tribal nomadic clothing to denote themselves as members of the ruling elite until c. 494 A.D. when Emperor Xiaowen of Northern Wei decreed a prohibition of Xianbei clothing among many other prohibition on Xianbei culture (e.g. language, Xianbei surnames) as a form of sinicization policies and allowed the intermarriage between Xianbei and Chinese elites. The Wei shu (魏書; the History of the Northern Wei) even claimed that the Xianbei rulers were descendants of Yellow Emperor just like the Han Chinese despite being non-Chinese. The Wei shu also records that Emperor Xiaowen of Northern Wei promoted Chinese-style long robes and official crowns in the court to display the wearer's rank and his hierarchical position in the court and ritual functions. For example, both male and female patrons appeared in Xianbei-style attire during the 5th century AD, this can be seen particular at the Yungang caves temples near Datong and in the earliest carvings at Longmen, whereas in the first third of the 6th century, the patrons tend to appear in Chinese-style clothing in the majority of Northern Wei caves at Longmen; this change in clothing style has been suggested to be the result of sinicization policies regarding the adoption of Chinese-style clothing in the Northern Wei court. Earliest images of nomadic Xianbei-style dress in China tend to be depicted as a knee-length tunic with narrow sleeves, with a front opening, which can typically be collarless, round-collared, and sometimes be V-neck collared; men and women tend to wear that knee-length tunic over trousers for men and long, ground-length skirts for women. When their tunics had lapelled, the lapel opening was typically zuoren. Xianbei people also wore Xianbei-style cloaks and xianbei hat (鮮卑帽; xianbei mao).

-

Emperor Xiaowen with his entourage, Central Bingyang cave, Longmen, Zhejiang; Northern Wei c.522-523.

Emperor Xiaowen with his entourage, Central Bingyang cave, Longmen, Zhejiang; Northern Wei c.522-523.

-

Procession of the Empress as Donor with Her Court, Chinese, from the Binyang Cave, Longmen, Henan Province, Northern Wei Dynasty, c.522 AD.

Procession of the Empress as Donor with Her Court, Chinese, from the Binyang Cave, Longmen, Henan Province, Northern Wei Dynasty, c.522 AD.

-

Procession of tomb occupant and his wives, mural painting from the tomb of General Cui Fen; Northern Qi.

Procession of tomb occupant and his wives, mural painting from the tomb of General Cui Fen; Northern Qi.

-

Procession, Gongyi, Henan Province, Northern Wei Dynasty.

Procession, Gongyi, Henan Province, Northern Wei Dynasty.

-

A pottery figure wearing Han Chinese style attire, Northern Wei (471 - 499 AD). The garment has a youren opening.

A pottery figure wearing Han Chinese style attire, Northern Wei (471 - 499 AD). The garment has a youren opening.

-

Male xianbei warrior wearing a cloak and xianbei hat, Northern Wei dynasty.

Male xianbei warrior wearing a cloak and xianbei hat, Northern Wei dynasty.

-

Female xianbei warrior wearing a cloak and xianbei hat, Northern Wei dynasty.

Female xianbei warrior wearing a cloak and xianbei hat, Northern Wei dynasty.

Despite the sinicization policies attempted by the Northern Wei court, the nomadic style clothing continued to exist in China until Tang dynasty. For example, narrow and tight sleeves, which was well adapted to nomadic life-style, started to be favoured and was adopted by Han Chinese. In the Shuiyusi temple of Xiangtangshan Caves dated back to Northern dynasties, male worshippers are usually dressed in Xianbei style attire while women are dressed in Han Chinese style attire wearing skirts and high-waisted, wrap-style robes with wide sleeves. Moreover, after the fall of the Northern Wei, tensions started to rise between the Western Wei (535 - 557 AD) (which was more sinicized) and the Eastern Wei (534 - 550 AD) (which was less sinicized and resented the sinicized court of Northern Wei). Due to the shift in politics, Han and non-Han Chinese ethnic tensions arose between the successor states of Northern Wei; and Xianbei-style clothing reappeared; however, their clothing had minor changes.

At the end of the Northern and Southern dynasties (420 - 589 AD), foreign immigrants started to settle in China; most of those foreign immigrants were traders and buddhists missionaries from Central Asia. Cultural diversity was also the most striking feature in China in the sixth-century AD. From the mural paintings found in the Tomb of Xu Xianxiu of the Northern Qi, various types of attire are depicted which reflect the internationalism and multiculturalism of the Northern Qi; many of the attire styles are derived from Central Asia or nomadic designs. The wife of Xu Xianxiu is depicted with a flying-bird bun; she is wearing a Han Chinese cross-collared, wide-sleeves attire which has the basic clothing design derived from the Han dynasty attire with some altered designs, such as a high waistline and wide standing collar. Xu Xianxiu is depicted wearing a Central Asian-style coat, Xianbei-style tunic, trousers, and boots. Some of the female servants depicted from the tomb murals of Xu Xianxiu are wearing what appears to be Sogdian dresses, which tend to be associated with dancing girls and low-status entertainers during this period, while the ladies-in-waiting of Xu Xianxiu's wife are wearing narrow-sleeved clothing which look more closely related to Xianbei-style or Central Asian-style clothing; yet this Xianbei style of attire is different from the depictions of Xianbei-style attire worn before 500 AD. The men (i.e. soldiers, grooms and male attendants) in the mural paintings of Xu Xianxiu tomb are depicted wearing high black or brown boots, belts, headgears, and clothing which follows the Xianbei-style, i.e. V-neck, long tunic which is below knee-length, with the left lapel of the front covering the right; narrow-sleeved tunic which is worn on top of round-collared undergarment are also depicted. High-waisted skirt style, which likely came from Central Asia, was also introduced to Han Chinese during the Northern Wei dynasty (386–535 AD).

-

A Northern Qi dynasty mural of a gate guard from the tomb of Lou Rui (婁叡).

A Northern Qi dynasty mural of a gate guard from the tomb of Lou Rui (婁叡).

-

Riders on Horseback; Tomb of Lou Rui, Northern Qi dynasty.

Riders on Horseback; Tomb of Lou Rui, Northern Qi dynasty.

-

The wife of Xu Xianxiu is wearing Han Chinese style clothing which derived from Han prototype with altered details such as high-waist and wide standing collar; Mural from Xu Xianxiu Tomb, Northern Qi, 571 AD.

The wife of Xu Xianxiu is wearing Han Chinese style clothing which derived from Han prototype with altered details such as high-waist and wide standing collar; Mural from Xu Xianxiu Tomb, Northern Qi, 571 AD.

-

The wife of the Xu Xianxiu in Han Chinese-style clothing, Mural painting from Xu Xianxiu Tomb, Northern Qi, 571 AD.

The wife of the Xu Xianxiu in Han Chinese-style clothing, Mural painting from Xu Xianxiu Tomb, Northern Qi, 571 AD.

-

A warrior in Xianbei-style costume, Northern Qi. The opening of the upper garment is zuoren.

A warrior in Xianbei-style costume, Northern Qi. The opening of the upper garment is zuoren.

-

Sogdian figures, wearing Sogdian clothing, Tomb of An Jia, 579 CE.

Sogdian figures, wearing Sogdian clothing, Tomb of An Jia, 579 CE.

Of note, significant changes occurred to the form of the garments which had been originally introduced by the Xianbei and other Turkic people who had settled in northern China after the fall of the Han dynasty; for example, in the arts and literature which dates from the 5th century, their male clothing appeared to represent the ethnicity of its wearer, but in the 6th century, the attire lost its ethnic significance and did not denote its wearer as Xianbei or non-Chinese. Instead, the nomadic dress had turned into a type of male ordinary dress in the Sui and early Tang dynasties regardless of ethnicity. On the other hand, the Xianbei women gradually abandoned their ethnic Xianbei clothing and adopted Han Chinese-style and Central Asian-style clothing to the point that by the Sui dynasty (581–605 AD), women in China were no longer wearing steppe clothing.

Sui, Tang, Five dynasties and Ten kingdoms period

See also: Popular fashion in ancient ChinaThe Sui and the Tang dynasties developed the pin se fu (品色服), which was a colour grading clothing system to differentiate social ranking; this colour grading system for clothing then continued to be developed in the subsequent dynasties.

Sui dynasty

Following the unification of China under the Sui dynasty (589 - 618 AD), the Sui court abolished the Northern Zhou rituals, it adopted the rituals, practices and ideas of the Han and Cao Wei dynasties, and the clothing code of the Han dynasty was restored. The Sui system was also based on the system of Western Jin and Northern Qi. The first emperor of Sui, Emperor Gaozu, would wear tongtianfu (通天服; celestial robe) on grand occasions, gunyi (衮衣; dragon robe) on suburban rites and visits to ancestral temple. He also set the colour red as the authoritative colour of the court imperial robes; this included the clothing of emperors and the ceremonial clothing of the princes. Crimson was the colour of martial clothing (i.e. chamber guards, martial guards, generals and duke generals) whereas servants would wear purple clothing, which consisted of hood and loose trousers. During Emperor Gaozu's time, the court official garment was similar to the clothing attire of the commoners, except that it was yellow in colour. Court censors during Emperor Gaozu wore the quefei guan (卻非冠; "the cap that rejects the wrong").

Emperor Yangdi later reformed the dress code in accordance of the ancient customs and news sets of imperial clothing were made. In 605 AD, it was decreed that officials over the fifth-ranks had to dress in crimson or purple, and in 611 AD, any officials who would follow the emperor in expedition together had to wear martial clothing. In 610 AD, the kuzhe (裤褶) attire worn by attending officials worn during imperial expeditions was replaced by the rongyi (戎衣) attire. Emperor Yangdi also wore several kind of imperial headgears, such as wubian (武弁; warrior cap) which derived from the ancient court officials headgear bian (弁), baishamao (白紗帽; white gauze cap), and the wushamao (烏紗帽; black gauze cap). Civil officials wore jinxian guan (進賢冠), and the wushamao (烏紗帽) was popular and was from court officials to commoners. The quefei guan (卻非冠) was replaced by the xiezhi guan (獬豸冠), another form of ancient hat, which could also be used to denote the censor's rank based on the material used.

During the Sui dynasty, an imperial decree which regulated clothing colour stated that lower class could only wear muted blue or black clothing; upper class on the other hand were allowed to wear brighter colours, such as red and blue. Women in the Sui dynasty wore short jackets with long skirts. Women's skirts in the Sui dynasty were characterized with high waistline which created a silhouette which looked similar to the Empire dresses of Napoleonic France; however, the construction of the assemble differed from the ones worn in Western countries as Han Chinese women assemble consisted of a separate skirt and upper garment which show low décolletage. In the Sui dynasty, ordinary men did not wear skirts anymore.

-

Painted pottery of a female attendant, Sui dynasty (581–618 AD).

Painted pottery of a female attendant, Sui dynasty (581–618 AD).

-

Painted pottery of a male attendant, Sui dynasty (581–618 AD).

Painted pottery of a male attendant, Sui dynasty (581–618 AD).

-

Female figurines of musicians, Sui dynasty from Zhang Sheng's Tomb.

Female figurines of musicians, Sui dynasty from Zhang Sheng's Tomb.

-

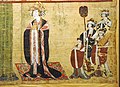

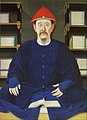

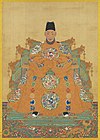

Emperor Yangdi, Emperor of Sui dynasty, with his servants, painting d. 7 century AD.

Emperor Yangdi, Emperor of Sui dynasty, with his servants, painting d. 7 century AD.

Tang dynasty and Five dynasties and Ten kingdoms period

Many elements of the Tang dynasty clothing traditions was inherited from the Sui dynasty. During the Tang dynasty (618 - 907 AD), yellow-coloured robes and shirts was reserved for emperors; a tradition which was kept until the Qing dynasty. Moreover, the subjects of Tang dynasty was forbidden from using ochre yellow colour as Emperor Gaozu of Tang used this colour for his informal clothing. The guan (冠) was replaced by futou (襆頭; black cap). Scholars and officials wore the futou (幞頭) along with the panling lanshan (盤領襴衫) which is a long, round-collar robe with long sleeves. Clothing colours and fabric materials continued to play a role in differentiating ranks; for example, officials of the three upper levels and princes had to wear purple robes; official above the fifth level had to wear red robes; officials of the sixth and seventh level had to wear green robes; and official of eighth and ninth levels had to wear cyan robes. Dragons-with-three-claws emblems also started to be depicted on the clothings of court officials above third ranks and on the clothing of princes; these dragon robes were first documented in 694 AD during the reign of Empress Wu Zetian. Common people wore white and soldiers wore black.

Common women attire in the Tang dynasty included shan (衫; a long overcoat or long blouse), ru (襦; a short sweater), banbi (半臂; a half-sleeved waistcoat), pibo (披帛), and qun (裙; usually wide, loose skirt which was almost ankle-length). The pibo (披帛), also known as pei (帔) in the Tang dynasty, is a long silk scarf; however it is not used to cover neck, sometimes it covers shoulders and other times just hangs from elbow. Regardless of social status, women in the Tang dynasty tend to be dressed in 3-parts clothing: the upper garment, the skirt, and the pibo (披帛). During the Tang dynasty, there were 4 kind of waistline for women skirts: natural waistline; low waistline; high waistline which reached the bust; and, high waistline above the bust, which could create different kind of women's silhouettes and reflected the ideal images of women of this period. This Tang dynasty-style ensemble would reappear several times even after the Tang dynasty, notably during Ming dynasty (1368-1644 AD). One of Tang dynasty's ensemble which consisted of a very short, tight-sleeved jackets and an empire-waisted skirt tied just below the bust-line with ribbons also strongly influenced the Korean Hanbok.

The women's clothing in the early Tang dynasty was quite similar to the clothing in the Sui dynasty; the upper garment was a short-sleeved short jacket with a low-cut; the lower garment was a tight-fitting skirt which was tied generally above the waist, and sometimes even up to the armpits, and a scarf was wrapped around their shoulders. The banbi was commonly worn on top of a plain top and was worn together with high-waisted, striped or one-colour A-line skirt in the seventh century. Red coloured skirts were very popular during the Tang dynasty.

-

A painted lay figure of a female dancer (wuyong); Tang Dynasty, 8th century AD.

A painted lay figure of a female dancer (wuyong); Tang Dynasty, 8th century AD.

-

A Group of Tang Dynasty Musicians from the Tomb of Li Shou (李壽) (577-630 AD), early Tang dynasty.

A Group of Tang Dynasty Musicians from the Tomb of Li Shou (李壽) (577-630 AD), early Tang dynasty.

-

A Tang Dynasty Woman with Flower, dressed in ruqun.

A Tang Dynasty Woman with Flower, dressed in ruqun.

-

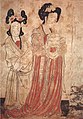

Court ladies of the Tang from Li Xianhui's tomb, Qianling Mausoleum, dated 706.

Court ladies of the Tang from Li Xianhui's tomb, Qianling Mausoleum, dated 706.

-

A Young Girl, Fresco from the Tomb of An Yüen-shou (安元壽) (607-683 A.D.), early Tang dynasty.

A Young Girl, Fresco from the Tomb of An Yüen-shou (安元壽) (607-683 A.D.), early Tang dynasty.

In the middle of the Tang dynasty, women who had a plump appearance were favoured; and thus, the clothings became looser, the sleeves became longer and wider, the upper garment became strapless, and a silk unlined upper garment was worn; they wore "breast dresses". This change in the ideal corporal shape of women body has been attributed to a beloved consort of Emperor Xuanzong of Tang, called Yang Guifei, although archeological evidence shows that this ideal form of female body had emerged before Yang Guifei's ascension to power in the imperial court.

-

A sancai figurine of a plump lady holding a Dog, Tang dynasty.

-

Sancai glazed female figurine Tang dynasty 618-907.

Sancai glazed female figurine Tang dynasty 618-907.

-

Tang Dynasty, sancai pottery, woman figurine.

-

Court lady figurine (Tang Dynasty 618 - 907), Heritage Museum Sha Tin Hong Kong.

Court lady figurine (Tang Dynasty 618 - 907), Heritage Museum Sha Tin Hong Kong.

-

Anonymous-Astana Graves Courtesan, c. 744, Tang dynasty.

Anonymous-Astana Graves Courtesan, c. 744, Tang dynasty.

-

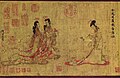

Painting of "A palace concert", Tang dynasty, c.836 - 907.

Painting of "A palace concert", Tang dynasty, c.836 - 907.

Another form of popular fashion in women's attire during the Tang dynasty is the wearing of male clothing; it was fashionable for women to dress in male attire in public and in everyday live, especially during the Kaiyuan and Tianbao (742 -756 AD) periods; this fashion started among the members of the nobility and the court maids and gradually spread in the community. Men's attire during the Tang dynasty usually included robes which was worn with trousers, yuanlingpao (圆领袍; round collar robe), belt worn at the waist, futou (襆頭; a black head scarf) or putou (幞頭; a turban-liked head wrap), and dark leather boots. The Tang dynasty inherited all the forms of belts which were worn in the Wei, Jin, Northern and Southern dynasties and adopted them in the official costumes of the military and civil officials. In some instances, however, Han Chinese-style robe continued to be depicted in arts showing court officials. In the Tang dynasty, the yuanlingpao (圆领袍) was worn by both men and women.

-

A group of eunuchs, Prince Zhanghuai's tomb, Tang dynasty, 706 AD.

-

Figures in a cortege wearing round-collar robe, from a wall mural in the Tang Dynasty Chinese tomb of Li Xian, 706 AD.

Figures in a cortege wearing round-collar robe, from a wall mural in the Tang Dynasty Chinese tomb of Li Xian, 706 AD.

-

Palace ladies; from Li Xian's tomb, Tang dynasty, 706 AD. The girl in the middle is wearing a yuanlingpao.

Palace ladies; from Li Xian's tomb, Tang dynasty, 706 AD. The girl in the middle is wearing a yuanlingpao.

-

Female servant in Tang dynasty dressed in a yuanlingpao; mid 8th century AD.

Female servant in Tang dynasty dressed in a yuanlingpao; mid 8th century AD.

-

Men wearing round collar gown with boots, belt, trousers; Mural painting from the Tomb of Wang Chuzhi, Five dynasties and Ten kingdoms period.

Men wearing round collar gown with boots, belt, trousers; Mural painting from the Tomb of Wang Chuzhi, Five dynasties and Ten kingdoms period.

The shoes worn by Han Chinese were lü (履), xi (shoes with thick soles), women's boots, and ji (屐; wooden clogs) with two spikes were worn when walking outside on muddy roads; in the South, xueji (靴屐; a type of boot-like clog) was developed. Some shoes were commonly curved in the front and was phoenix-shaped.

The Tang dynasty represents a golden age in China's history, where the arts, sciences and economy were thriving. Female dress and personal adornments in particular reflected the new visions of this era, which saw unprecedented trade and interaction with cultures and philosophies alien to Chinese borders. Although it still continues the clothing of its predecessors such as Han and Sui dynasties, fashion during the Tang dynasty was also influenced by its cosmopolitan culture and arts. Where previously Chinese women had been restricted by the old Confucian code to closely wrapped, concealing outfits, female dress in the Tang dynasty gradually became more relaxed, less constricting and even more revealing. The Tang dynasty also saw the ready acceptance and syncretisation with Chinese practice, of elements of foreign culture by the Han Chinese. The foreign influences prevalent during Tang China included cultures from Gandhara, Turkestan, Persia and Greece. The stylistic influences of these cultures were fused into Tang-style clothing without any one particular culture having especial prominence.

An example of foreign influence on Tang's women clothing is the use of garment with a low-cut neckline. Women were also allowed to fashioned themselves into hufu (胡服) (i.e. foreign dress, which included the clothing of the Tartars or clothing of the people who lived in the Western Regions during this period). Popular menswear such as Persian-style round collared robes with tight sleeves and a central band decorated with flowers on the front was also popular among Tang dynasty's women; this Persian-style round collared robe is different from the local worn yuanlingpao (圆领袍). Long Persian trousers and knickers were also worn by women as a result of the cultural and economic exchanges which took place. Stripped trousers were also worn. The Chinese trousers during the Tang dynasty were narrow compared to the dashao (大袑) and the dakouku (大口裤) trousers worn in the preceding dynasties. Another popular garment worn in the 7th and 8th centuries which originated from Central Asia was the kuapao robe. It was a kaftan-like robe with tight-fitting sleeves, double overturned lapels, and a front opening; the kuapao could be used as main garment for cross-dressing attendants or could be draped across the shoulders like a cloak. The kuapao was also worn by men.

-

Woman wearing hufu in Tang Dynasty.

Woman wearing hufu in Tang Dynasty.

-

A sancai figurine of a woman holding a parrot, Tang dynasty.

A sancai figurine of a woman holding a parrot, Tang dynasty.

The headwear of the women in Tang dynasty also demonstrates evidence of foreign clothing inclusion in their attire. In Taizong's era, women wore a burqa-like mili (羃䍦) which concealed the entire body when horse back riding; the trend changed to the use of weimao (帷帽; a veiled curtain hat) during the reign of Emperor Gaozong of Tang and Wu Zetian; and after that, during the early reign of Emperor Xuanzong of Tang, women started wearing a veil-less hat called humao (胡帽; translated literally as "barbarian hat"); women eventually stopped wearing hats when horse riding, and by the 750's, women dressing in men's garments became popular.

Noble women of the Tang dynasty wore the veil, and after the Yonghui reign the veil with hat was worn. The Tang dynasty veils covered the women's face and neck. Song dynasty women continued to wear this Tang dynasty women's veil which covered the head and upper body despite its barbarian origin. The mili appears to have been adopted from the Tuyuhun ethnic minority of Qinghai which was worn by both men and women in the late 6th century; but full-body mili in the Tang dynasty was worn as a way to conceal the entire body, and thus it was considered as protecting women's modesty. The full-body veil was worn in both Sui and Tang dynasties. The full-body veil originating from the Rong and Yi barbarians started to be worn by Chinese women of noble and aristocratic families during the Sui dynasty and was enforced with laws during the Tang dynasty to make women wear it since women started abandoning it for the weimao which only covered the head and face. It was to stop strangers from seeing women and viewed as proprietious. When the full-body veil fashion started to fell out of favour, Emperor Gaozong of Tang issued imperials edict twice to order women to abandon the wear of weimao and returned to the burqa-like mili, covering the head and body with only a slit for vision, in order to stop women from being seen by men to enforce public decency. Due those imperial edicts, women decided to wear hoods that only let the face be shown or a veil that covered the sides of their head hanging from a broad rimmed hat with a veil, a curtain bonnet which originated from Tokâra; however, the Emperor Gaozong was not even satisfied with these because they let the face be shown and he wanted the burnoose to return and cover the face. However, his imperial edicts were only effective for a short period of time as the women started re-wearing the weimao. By the time of Wu Zetian's ascendancy, the weimao was back to fashion while the mili had gradually disappeared. After the mid-seventh century, the social expectation that women had to hide their faces in public disappeared. It was also fashionable for noble women to wear Huihuzhuang (回鶻装; Uyghur dress, which is sometimes referred as Huihu-style), a turned-down lapel voluminous robes with tight sleeves which were slim-fitting, after the An Lushan Rebellion (755 - 763 AD). Another trend which emerged after the An Lushan Rebellion is the sad and depressed-look while looking exquisite which reflected the instability of the political situation in this period. Of note, just like women in the Tang dynasty period incorporated Central Asian-styles in their clothing, Central Asian women were also wearing some Han Chinese-style clothing from the Tang dynasty and/or would combine elements of the Han Chinese-style attire and ornament aesthetic in their ethnic attire. In 840 AD, the Uyghur empire collapsed, the Uyghur refugees fled to Xinjiang and to the Southeast of Tang frontier to seek refuge, and in 843 AD, all the Uighur living in China had to wear Chinese-style clothing.

The influence of hufu eventually faded after the High Tang period, and women's clothing gradually regain a broad and loose fitting, and more traditional Han style clothing was restored. The sleeve width of women's garments for ordinary women was more than 1.3 meters. The daxiushan, (大袖衫; a "dress with broad sleeves") for example, was made of an almost transparent, thin silk; it featured beauty design and pattern on it and its sleeves were so broad that it was more than 1.3 meters. Based on the painting, "Court ladies adorning their hair with flowers" (簪花仕女圖; Zanhua shinü tu), a painting attributed to the painter Zhou Fang (active in the late 8th to early 9th century), women clothing was depicted as a sleeveless gown which was worn under a robe with wide sleeves, with the use of a shawl as an ornament; some of the women painted are fashioned with skirts while others are seen wearing an overskirt above on an underskirt; it is speculated that shawls and cloaks during this period were made from a silk-netted sheer gauze fabric material.

-

A painting of Tang dynasty women playing with a dog, by artist Zhou Fang, 8th century.

A painting of Tang dynasty women playing with a dog, by artist Zhou Fang, 8th century.

-

Buddhist donors of late Tang dynasty.

Buddhist donors of late Tang dynasty.

-

A noble lady from the painting Bodhisattva Who Leads the Way, Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms.

A noble lady from the painting Bodhisattva Who Leads the Way, Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms.

-

Buddhist donatress Chang, Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms.

Buddhist donatress Chang, Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms.

-

Lady musicians in a raised-relief, Tomb of Wang Chuzhi (d. 923AD) from the Capital Museum in Beijing, dated to the Five Dynasties and the Ten Kingdoms Period (907-960 AD).

Lady musicians in a raised-relief, Tomb of Wang Chuzhi (d. 923AD) from the Capital Museum in Beijing, dated to the Five Dynasties and the Ten Kingdoms Period (907-960 AD).

-

Mural of Wang Chuzhi tomb, Southern Tang.

Mural of Wang Chuzhi tomb, Southern Tang.

-

Women of Southern Tang holding a baby, 10th century AD.

Women of Southern Tang holding a baby, 10th century AD.

-

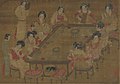

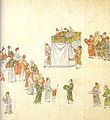

Men and women in the Night Revels of Han Xizai painting, copy after the original painting of Southern Tang painter, Gu Hongzhong.

Men and women in the Night Revels of Han Xizai painting, copy after the original painting of Southern Tang painter, Gu Hongzhong.

-

Men and women in the Night Revels of Han Xizai painting, copy after the original painting of Southern Tang painter, Gu Hongzhong.

Men and women in the Night Revels of Han Xizai painting, copy after the original painting of Southern Tang painter, Gu Hongzhong.

-

A Buddhist donor from early Northern Song dynasty.

A Buddhist donor from early Northern Song dynasty.

Song dynasty

See also: Popular fashion in ancient ChinaThe Song dynasty (960 - 1279 AD) clothing system was established at the beginning of the Northern Song dynasty (960 - 1127 AD). Clothes could be classified into two major types: officials garments (further differentiated between court clothing and daily wear), and the garment for ordinary people. Some features of Tang dynasty clothing were carried into the Song dynasty, such as court dress. Song dynasty court dress often used red colour, with accessories made of different colours and materials, black leather shoes and hats. The officials had specific clothing for different occasions: (1) the sacrificial dress, a vermillion colour garment worn when attending ancestral temple or grand ceremonies, which they had to wear with the proper hats, i.e. jinxian guan (進賢冠), diaochan guan (貂蟬冠) or xiezhi guan (獬豸冠); (2) the court dress, which was worn when attending court meeting held by the Emperor and sometimes during sacrificial rituals; and (3) the official gown, worn daily by officials who held ranks. The form of officials' daily dresses had the same design regardless of rank: round-collared robe with long and loose sleeves; however, the officials were bound to wear different colours according to ranks. As the Song dynasty followed the Tang dynasty's clothing system, officials of third ranks and above wore purple gown; fifth ranks officials wore vermillion gown; seventh ranks officials and above wore green gowns; and the ninth rank officials and above wore black gown. However, after the Yuanfeng period, changes were imposed on the colour system of the official gowns: officials of the fourth rank and above wore purple gown, the sixth rank and above wore crimson gown; and the ninth rank and above officials wore green gown; this noted the removal of black colour as a colour for the official dress. Officials also wore leather belts and kerchiefs as ornaments. If senior officials were allowed to wear purple or crimson official garments, they had to wear a silver or gold fish-shaped bag as ornament. The official gown were worn with different styles of futou (襆頭) and guan (冠) as headwear. For example, jinxian guan (进贤冠) was worn by general officials; diaochan guan (貂蝉冠), also known as longjin (笼巾; cage kerchief), was worn by senior officials; and xiezhi guan (獬豸冠), also called the "Legal hat", was worn by enforcement officials.

-

Male Buddhist Donor, Northern Song dynasty, 981 AD.

Male Buddhist Donor, Northern Song dynasty, 981 AD.

-

Eight riders in Spring, Song dynasty.

Eight riders in Spring, Song dynasty.

-

The Chinese Emperor during the Civil Service Examination, Song dynasty.

The Chinese Emperor during the Civil Service Examination, Song dynasty.

-

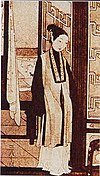

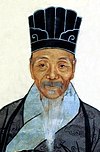

A painting of Sima Guang, Song dynasty.

A painting of Sima Guang, Song dynasty.

The apparels for court gathering in the Song dynasty was tongtianguanfu (通天冠服); it was worn by the most senior officials who served the emperor directly; it was the most important clothing after the clothing worn by the emperor. The tongtianguanfu was the combination of a deep red gown with dragons in clouds embroidery, a deep red trousers, a white shirt, white stockings, black shoes; personal ornaments, belt of gold or jade, a tall hat called tongtian guan (通天冠), and personal ornaments were also worn with the tongtianguanfu.

The clothes worn by Song dynasty emperors are collectively called tianzi apparel (天子服饰; the emperor's apparel). The apparels worn when attending sacrificial and worshipping ceremonies were daqiumian (大裘冕; a type of mianfu), gunmian (衮冕; a type of mianfu), and lüpao (履袍). The emperor's daily wears were shanpao (衫袍) and zhaipao (窄袍). The yuyue fu (御阅服) was the formal military uniform worn by the Song dynasty Emperors and only came into existence in the Southern Song dynasty (1127 - 1279 AD). The crown prince would wear the gunmian (衮冕) when he would accompanied the emperor to sacrificial ceremonies, and he would wear yuanyouguanfu (远游冠服) and zhumingfu (朱明衣) on less formal but important occasions such as nobility conferring and appointment, when paying visits to the founding ancestor's temple and when attending court meetings which are held by the Emperor. The Crown prince also wear purple official dress, gold and jade waistband, and wore a folding-up black muslin scarf on his head.

Although some of clothing in the Song dynasty have similarities with previous dynasties, some unique characteristics separate it from the rest. While most of them following the Tang dynasty style, the revival of Confucianism influenced the women clothing of the Song dynasty; Confucians in the Song dynasty revered antiquity and wanted to revive some old ideas and customs and encouraged women to reject the extravagance of the Tang dynasty fashion. Due to the shift in philosophical thought, the aesthetics of the Song dynasty clothing showed simplicity and became more traditional in style. Palace ladies searched for guidance in the Rites of Zhou on how to dress accordingly to ceremonial events and carefully chose ornaments which were graded for each occasion based on the classic rituals. While women of the Tang dynasty liked clothing which emphasized on body curves and sometimes revealed décolletage, women in the Song dynasty perceived such styles as obscene and vulgar and preferred slender body figure. Donning clothing which looked simple and humble instead of extravagant was interpreted as expressing sober virtue. The Song dynasty clothing system also specified how women of the imperial court had to dress themselves and this included the Song empresses, the imperial concubines, and the titled gentlewomen; their clothing would also change depending on occasions. Song dynasty empresses wear the huiyi (褘衣); they often had three to five distinctive jewelry-like marks on their face (two side of the cheek, other two next to the eyebrows and one on the forehead). The everyday clothing of the Empresses and Imperial concubines included: long skirts, loose-sleeves garments, tasselled capes and beizi. Imperial concubines like the colour yellow and red; the pomegranate colour skirt was also popular in the Song dynasty. Collar edges and sleeve edges of all clothes that have been excavated were decorated with laces or embroidered patterns. Such clothes were decorated with patterns of peony, camellia, plum blossom, and lily, etc. Pleated skirts were introduced and became the characteristic skirts of the upper social class.

-

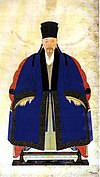

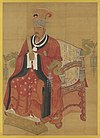

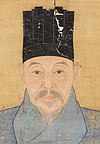

Portrait of Song Taizu wearing a white round-collar gown and a zhanchi futou (展翅幞頭; lit. spread wings hat), c.1000 AD.

Portrait of Song Taizu wearing a white round-collar gown and a zhanchi futou (展翅幞頭; lit. spread wings hat), c.1000 AD.

-

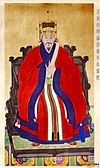

Empress Cao wearing a huiyi with two court ladies wearing a round-collar gown with red pleated skirts, Song dynasty.

Empress Cao wearing a huiyi with two court ladies wearing a round-collar gown with red pleated skirts, Song dynasty.

-

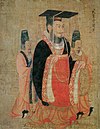

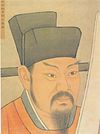

A Song dynasty period painting of Emperor Wen of Han in bianfu.

A Song dynasty period painting of Emperor Wen of Han in bianfu.

-

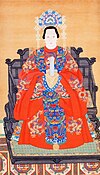

Emperor and empress, Fresco from the Temple of Enlightenment - Life of Buddha, Song dynasty.

Emperor and empress, Fresco from the Temple of Enlightenment - Life of Buddha, Song dynasty.

One of the common clothing styles for woman during the Song dynasty was beizi (褙子), which were usually regarded as shirt or jacket and could be matched with ru (襦; a jacket), which was a necessary clothing for daily life of commoners, a qun (裙; skirt) or ku (袴; trousers). There are two size of beizi: the short one is crown rump length and the long one extended to the knees. According to the sacrificial and ceremonial apparel system drafted by Zhu Xi, women should wear an overcoat, a long skirt, and the beizi. Other casual forms of clothing included: the pao (袍; the gown which could be broad or narrow-sleeved), ao (襖; a necessary coat for commoner in their daily lives), duanhe (短褐; a short, coarse cloth jacket worn by people of low socioeconomic status), lanshan (襴衫), and zhiduo (直裰). According to the regulations, ordinary people were only allowed to wear white clothes; but at some point, the regulations changed and ordinary people, as well as administrative clerks and intellectuals, were able to wear black clothes. However, in reality, the clothing worn by civilians were much more colourful than what was stipulated as many colours were used in the garments and skirts. Han Chinese women's skirts worn in the Song dynasty included the liangpian qun (两片裙), a wrap skirt which consist of two pieces of fabric sewn to a separate, single waistband with ties. Ordinary people also dressed differently accordingly to their social status and occupations. A painting, called Sericulture, by the painter Liang Kai in Southern Song dynasty depicts rural labourers in the process of making silk. Foot binding also became popular in the Song dynasty at the end of the dynasty.

-

Song dynasty painting, 12th century.

Song dynasty painting, 12th century.

-

A working woman who is wearing trousers, Song dynasty painting.

A working woman who is wearing trousers, Song dynasty painting.

-

Song dynasty women wearing beizi; Northern Song dynasty.

Song dynasty women wearing beizi; Northern Song dynasty.

-

Song Dynasty Tomb Painting Found in Tengfeng City 6.

Song Dynasty Tomb Painting Found in Tengfeng City 6.

-

A Song period mural depicts a scene of the daily life of the occupant, found in a tomb unearthed in Dengfeng.

A Song period mural depicts a scene of the daily life of the occupant, found in a tomb unearthed in Dengfeng.

-

Children Playing in an Autumn Courtyard, 12th century AD, Song Dynasty.

Children Playing in an Autumn Courtyard, 12th century AD, Song Dynasty.

-

Playing Children, Painting from the mid-12th century; Song dynasty.

Playing Children, Painting from the mid-12th century; Song dynasty.

-

Weighing and sorting the cocoons, from the painting Sericulture, Southern Song dynasty, c.1200 AD.

Weighing and sorting the cocoons, from the painting Sericulture, Southern Song dynasty, c.1200 AD.

-

Poet Li Bai in Stroll (李白行吟圖). A 減筆畫 (lit. minimalist painting) by Liang Kai of Southern Song dynasty. Note that Li Bai is depicted with his bun exposed, possibly due to the poet's heavy Taoist influence. The painting is currently kept in Tokyo National Museum.

Poet Li Bai in Stroll (李白行吟圖). A 減筆畫 (lit. minimalist painting) by Liang Kai of Southern Song dynasty. Note that Li Bai is depicted with his bun exposed, possibly due to the poet's heavy Taoist influence. The painting is currently kept in Tokyo National Museum.

In addition, Neo-Confucian philosophies also determined the conduct code of the scholars. The Neo-Confucians re-constructed the meaning of the shenyi, restored, and re-invented it as the attire of the scholars. Some Song dynasty scholars, such as Zhu Xi and Shaoyong, made their own version of the scholar gown, shenyi, based on The book of Rites, while scholars such as Jin Lüxiang promoted it among his peers. However, the shenyi used as a scholar gown was not popular in the Song dynasty and was even considered as "strange garment" despite some scholar-officials appreciated it.

In the capital of Southern Song, clothing-style from Northern China were popular. The Song dynasty court repeatedly banned people (i.e. common people, literati, and women) from wearing clothing and ornaments worn by Khitan people, such as felt hats, and from the wearing of exotic clothing. They also banned clothing with colours which was associated to Khitan clothing; such as aeruginous or yellowish-black. They also banned people, except for drama actors, from wearing Jurchen and Khitan diaodun (釣墩; a type of lower garment where the socks and trousers were connected to each other) due to its foreign ethnic nature. Many of Song dynasty clothing was adopted in the Yuan and Ming dynasties.

Liao, Western Xia, and Jin dynasties

Liao dynasty