This is an old revision of this page, as edited by 70.242.131.201 (talk) at 02:46, 30 January 2007. The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 02:46, 30 January 2007 by 70.242.131.201 (talk)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) For other uses, see Ebola (disambiguation).

| Ebola virus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Virus classification | |

| Group: | Group V ((−)ssRNA) |

| Order: | Mononegavirales |

| Family: | Filoviridae |

| Genus: | Ebolavirus |

| Species: | Reston Ebolavirus Sudan Ebolavirus Ivory Coast Ebolavirus Zaïre Ebolavirus |

| Ebola | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Infectious diseases |

Ebola is the common term for a group of viruses belonging to genus Ebolavirus, family [[so called matrix space, the viral proteins VP40 and VP24 are located.

by itself is not infectious, beI KILLED THE ARTICAL!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!1

Species

Zaïre Ebolavirus

The Zaïre Ebolavirus has the highest mortality rate, up to 90% in some epidemics, with an average of approximately 83% mortality over 27 years. The case-fatality rates were 88% in 1976, 100% in 1977, 59% in 1994, 81% in 1995, 73% in 1996, 80% in 2001-2002 and 90% in 2003. There have been more outbreaks of Zaïre Ebolavirus than any other strain.

The first outbreak took place on August 26, 1976 in Yambuku, a town in the north of Zaïre. The first recorded case was Mabalo Lokela, a 44-year-old schoolteacher returning from a trip around the north of the state. His high fever was diagnosed as possible malaria and he was subsequently given a quinine shot. Lokela returned to the hospital every day. A week later, his symptoms included uncontrolled vomiting, bloody diarrhea, headache, dizziness, and trouble breathing. Later, he began bleeding from his nose, mouth, and rectum. Mabalo Lokela died on September 8, 1976, roughly 14 days after the onset of symptoms.

Soon after, more patients arrived with varying but similar symptoms including fever, headache, muscle and joint aches, fatigue, nausea and dizziness. These often progressed to bloody diarrhea, severe vomiting, and bleeding from the nose, mouth, and rectum. The initial transmission was believed to be due to reuse of the needle for Lokela’s injection without sterilization. Subsequent transmission was also due to care of the sick patients without barrier nursing anMWAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHaHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAd the traditional burial preparation method, which involved washing and gastrointestinal tract cleansing.

Sudan Ebolavirus

Sudan Ebolavirus was the second strand of Ebola reported in 1976. It apparently originated amongst cotton factory workers in Nzara, Sudan. The first case reported was a worker exposed to a potential natural reservoir at the cotton factory. Scientists tested all animals and insects in response to this, however none tested positive for the virus. The carrier is still unknown.

A second case involved a nightclub owner in Nzara, Sudan. The local hospital, Maridi, tested and attempted to treat the patient; however, nothing was successful, and he died. The nurses did not apply safe and practical procedures in sterilizing and disinfecting the medical tools used on the nightclub owner, facilitating the spread of the virus in the hospital.EGGGS

The most recent outbreak of Sudan Ebolavirus occurred in May 2004. As of May 2004, 20 cases of Sudan Ebolavirus were reported in Yambio County, Sudan, with 5 deaths resulting. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention confirmed the virus a few days later. The neighbouring countries of Uganda and the Democratic Republic of Congo have increased surveillance in bordering areas, and other similar measures have been taken to control the outbreak. The average fatality rates for Sudan Ebolavirus were 53% in 1976, 68% in 1979, and 53% in 2000/2001. The average case-fatality rate is 53.76%.

Reston Ebolavirus

Main article: Ebola RestonFirst discovered in November of 1989 in a group of 100 Crab-eating monkeys (Macaca fascicularis) imported from the Philippines to Reston, Virginia. A parallel infected shipment was also sent to Philadelphia. This strain was highly lethal in monkeys, but did not cause any fatalities in humans. Six of the Reston primate handlers tested positive for the virus, two due to previous exposure.

Further Reston Ebolavirus infected monkeys were shipped again to Reston, and Alice, TexPIRATES I AM A PIRATEass in February of 1990. More Reston Ebolavirus infected monkeys were discovered in 1992 in Siena, Italy and in Texas again in March 1996. A high rate of co-infection with Simian Hemorrhagic Fever (SHF) was present in all infected monkeys. No human illness has resulted from these two outbreaks.

Ivory Coast Ebolavirus

This species of Ebola was first discovered amongst chimpanzees of the Tai Forest in Côte d’Ivoire, Africa. On November 1, 1994, the corpses of two chimpanzees were found in the forest. Necropsies showed blood within the heart to be liquid and brown, no obvious marks seen on the organs, and one presented lungs filled with liquid blood. Studies of tissues taken from the chimps showed results similar to human cases during the 1976 Ebola outbreaks in Zaïre and Sudan. Later in 1994, more dead chimpanzees were discovered, with many testing positive to Ebola using molecular techniques. The source of contamination was believed to be the meat of infected Western Red Colobus monkeys, which the chimpanzees preyed upon.

One of the scientists performing the necropsies on the infected chimpanzees contracted Ebola. She developed syndromes similar to dengue fever approximately a week after the necropsy and was transported to Switzerland for treatment. After two weeks she was discharged from hospital, and was fully recovered six weeks after the infection.

Replication

The viral attachment protein recognizes specific receptors, which may be protein, carbohydrate or lipid, on the outside of the cell. The mechanism of virus entry into host cells is unknown, but it is reasonable to assume that the glycoprotein spikes on the surfWHAT WAHAT WHAT MY HAT? WHAT YOU KILLED THE ARTICLE?

Ebola hemorrhagic fever

Symptoms

Symptoms are varied and often appear suddenly. Initial symptoms include: high fever (at least 38.8°C/101°F), severe headache, muscle, joint, or abdominal pain, severe weakness and exhaustion, sore throat, nausea, and dizziness. Before an outbreak is suspected, these early symptoms are easily mistaken for malaria, typhoid fever, dysentery, influenza, or various bacterial infections, which are all far more common.

Ebola goes on to cause diarrhea, dark or bloody stool, vomiting blood, red eyes from swollen blood vessels, red spots on the skin from subI NOTEY CHORDMAN KILLED THE ARTICLEWHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHEEEEEEEEEEEmembrane contact. The incubation period can be anywhere from 2 to 21 days, but is generally between 5 and 10 days.

Although airborne transmission between monkeys has been demonstrated in a laboratory, there is very limited evidence for human-to-human airborne transmission in any reported epidemics. Nurse Mayinga might represent the only possible case. The means by which she contracted the virus remain uncertain.

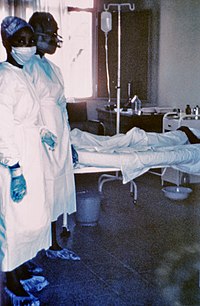

So far all epidemics of Ebola have occurred in sub-optimal hospital conditions, where practices of basic hygiene and sanitation are often either luxuries or unknown to caretakers and where disposable needles and autoclaves are unavailable or too expensive. In modern hospitals with disposable needles and knowledge of basic hygiene and barrier nursing techniques, Ebola rarely spreads on such a large scale.

In the early stages, Ebola may not be highly contagious. Contact with someone in early stages may not even transmit the disease. As the illness progresses, bodily fluids from diarrhea, vomiting, and bleeding represent an extreme biohazard. Due to lack of proper equipment and hygienic practices, large scale epidemics occur mostly in poor, isolated areas without modern hospitals and/or well-educated medical staff. Many areas where the infectious reservoir exists have just these characteristics. In such environments all that can be done is to immediately cease all needle sharing or use without adequate sterilization procedures, to isolate patients, and to observe strict barrier nursing procedures with the use of a medical rated disposable face mask, gloves, goggles, and a gown at all times. This should be strictly enforced for all medical personnel and visitors.

Treatments

Treatment is primarily supportive and includes minimizing invasive procedures, balancing electrolytes, replacing lost coagulation factors to help stop bleeding, maintaining oxygen and blood levels, and treating any complicating infections. Despite some initial anecdotal evidence, blood serum from Ebola survivors has been shown to be ineffective in treating the virus. Interferon is also thought to be ineffective. In monkeys, administration of an inhibitor of coagulation (rNAPc2) has shown some benefit, protecting 33% of infected animals from a usually 100% (for monkeys) lethal infection. In early 2006, scientists at USAMRIID announced a 75% recovery rate after infecting four rhesus monkeys with Ebola virus and administering antisense drugs.

Vaccines

Vaccines have been produced for both Ebola and Marburg that were 100% effective in protecting a group of monkeys from the disease. These vaccines are based on either a recombinant Vesicular stomatitis virus or a recombinant Adenovirus carrying the Ebola spikeprotein on its surface. Early human vaccine efforts, like the one at NIAID in 2003, have so far not reported any successes.

Viral Reservoir

Despite numerous studies, the wildlife reservoir of Ebolavirus has not been identified. Between 1976 and 1998, from 30,000 mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians and arthropods sampled from outbreak regions, no Ebolavirus was detected apart from some genetic material found in six rodents (Mus setulosus and Praomys species) and a shrew (Sylvisorex ollula) collected from the Central African Republic in 1998. Ebolavirus was detected in the carcasses of gorillas, chimpanzees and duikers during outbreaks in 2001 and 2003 (the carcasses were the source of the initial human infections) but the high mortality from infection in these species precludes them from acting as reservoirs.

Plants, arthropods and birds have also been considered as reservoirs, however bats are considered the most likely candidate. Bats were known to reside in the cotton factory in which the index cases for the 1976 and 1979 outbreaks were employed and have also been implicated in Marburg infections in 1975 and 1980. Of 24 plant species and 19 vertebrate species experimentally inoculated with Ebolavirus, only bats became infected. The absence of clinical signs in these bats is characteristic of a reservoir species. In 2002-03, a survey of 1,030 animals from Gabon and the Republic of the Congo including 679 bats found Ebolavirus RNA in 13 fruit bats (Hyspignathus monstrosus, Epomops franquetti and Myonycteris torquata). Bats are also known to be the reservoirs for a number of related viruses including Nipah virus, Hendra virus and lyssaviruses.

Ebola as a Weapon

Ebola is classified as a Category A Biological terrorism agent by the CDC as well as being considered a select agent that has the "potential to pose a severe threat to public health and safety". Ebola was considered in biological warfare research at both Fort Detrick in the United States and Biopreparat in the Soviet Union during the Cold War.

Ebola shows potential as a biological weapon because of its lethality but due to its relatively short incubation period it may be more difficult to spread since it may kill its victim before it has a chance to be transmitted. As a result, some developers have considered breeding it with other agents such as smallpox to create so-called chimera viruses.

As a terrorist weapon, Ebola has been considered by members of Japan's Aum Shinrikyo cult, whose leader, Shoko Asahara led about 40 members to Zaire in 1992 under the guise of offering medical aid to Ebola victims in what was presumably an attempt to acquire a sample of the virus.

Cultural effects

Popular description and representation

Ebola and Marburg have served as a rich source of ideas and plotlines for many forms of entertainment. The infatuation with the virus is likely due to the high mortality rate of its victims, its mysterious nature, and its tendency to cause gruesome bleeding from body orifices.

Much of the representation of the Ebola virus in fiction and the media is considered exaggerated or myth. Many of the stories about Ebola in Preston's book The Hot Zone are refuted in the book Level 4: Virus Hunters of the CDC by Joseph B. McCormick, an employee of the CDC at the time of the early outbreaks. One pervasive myth follows that the virus kills so fast that it has little time to spread. Victims die very soon after contact with the virus. In reality, the incubation time is usually about a week. The average time from onset of early symptoms to death varies in the range 3-21 days, with a mean of 10.1. Although this would prevent the transmission of the virus to many people, it is still enough time for some people to catch the disease.

Another myth states that the symptoms of the virus are horrifying beyond belief. Victims of Ebola suffer from squirting blood, liquefying flesh, zombie-like faces and dramatic projectile bloody vomiting, at times, from even recently deceased. In actual fact, only a fraction of Ebola victims have severe bleeding that would be even somewhat dramatic to witness. Approximately 10% of patients suffer some bleeding, but this is often internal or subtle, such as bleeding from the gums. Ebola symptoms are usually limited to extreme exhaustion, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, a high fever, headaches and other body pains.

The following is an excerpt from an interview with Philippe Calain, M.D. Chief Epidemiologist, CDC Special Pathogens Branch, Kikwit 1996:

At the end of the disease the patient does not look, from the outside, as horrible as you can read in some books. They are not melting. They are not full of blood. They're in shock, muscular shock. They are not unconscious, but you would say 'obtunded', dull, quiet, very tired. Very few were hemorrhaging. Hemorrhage is not the main symptom. Less than half of the patients had some kind of hemorrhage. But the ones that had bled, died.

Cultural impact

Main article: Ebola inspired entertainment| This section needs expansion. You can help by making an edit requestadding to it . |

See also

- Bolivian haemorrhagic fever

- Crimean Congo hemorrhagic fever (CCHF)

- Marburg haemorrhagic fever, the first known disease caused by a filovirus

- Matthew Lukwiya, Ugandan doctor at the forefront of the 2000 outbreak

References

- http://virus.stanford.edu/filo/eboci.html

- http://www.usamriid.army.mil/press%20releases/warfield_press_release.pdf

- Jones et al. “Live attenuated recombinant vaccine protects nonhuman primates against Ebola and Marburg viruses”, Nat Med. 2005 Jul, 11(7):786-790

- Sullivan et al. “Accelerated vaccination for Ebola virus haemorrhagic fever in non-human primates”, Nature 2003 Aug, 424(6949):602

- NIAID Ebola Vaccine Enters Human Trial, November 18, 2003

- ^ Pourrut, X, Kumulungui, B, Wittmann, T et al. (2005). The natural history of Ebola virus in Africa. Microbes and Infection. 7:1005–1014.

- Morvan, JM, Deubel, V, Gounon, P et al. (1999). Identification of Ebola virus sequences present as RNA or DNA in organs of terrestrial small mammals of the Central African Republic. Microbes and Infection. 1:1193–1201.

- Swanepoel, R, Leman, PA, Burt, FJ. (1996). Experimental inoculation of plants and animals with Ebola virus. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2:321–3215.

- Leroy, EM, Kimulugui, B, Pourrut, X et al. (2005). Fruit bats as reservoirs of Ebola virus. Nature. 438:575–576.

- http://www.medicalnewstoday.com/medicalnews.php?newsid=6042,

- http://www.technologyreview.com/read_article.aspx?ch=biotech&sc=&id=16485&pg=4

- http://www.zkea.com/archives/archive02006.html

- http://cns.miis.edu/pubs/reports/pdfs/aum_chrn.pdf

Further reading

- Lethal experimental infection of rhesus monkeys with Ebola-Zaire (Mayinga) virus by the oral and conjunctival route of exposure PubMed, February 1996, Jaax et al.

- Transmission of Ebola virus (Zaire strain) to uninfected control monkeys in a biocontainment laboratory PubMed, December 1993

- Lethal experimental infections of rhesus monkeys by aerosolized Ebola and marburg virus PubMed, August 1995

- Marburg and Ebola viruses as aerosol threats PubMed, 2004, USAMRIID

- Other viral bioweapons: Ebola and Marburg hemorrhag fever PubMed, 2004

- Questions and Answers about Ebola Hemorrhagic Fever, Center for Disease Control (CDC), retrieved 10 July 2006

- ICTVdB database entry on genus Ebolavirus

- Infection Control for Viral Hemorrhagic Fevers in the African Health Care Setting - Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, December 1998

- History of Ebola Outbreaks - Centers for Disease Control Special Pathogens Branch, retrieved 10 July 2006

- Draper, Allison Stark. Ebola. New York: The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc., 2002

- Horowitz, Leonard G. Emerging Viruses: "FINALLY THE STD'S....WHERE ARE THE EGGS" AIDS & Ebola — Nature, Accident, or Intentional?. Rockport, MA: Tetrahedron, Inc., 1996

- Regis, Ed. Virus Ground Zero; Simon & Schuster: New York, 1996; p104

- J. Infect. Dis. 1999 179 S1-S7

- Merck Research Laboratories. The Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy, Seventeenth Edition; Merck Research Laboratories: Whitehouse Station, N.J.; pg 1311

External links

- Ebola cases and outbreaks – Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- Ebola Virus Haemorrhagic Fever - a comprehensive overview of the disease

- Death Called a River - Jason Socrates Bardi, Scripps Research Institute

- What is the probability of a dangerous strain of Ebola mutating and becoming airborne? Brett Russel, retrieved 10 July 2006

- WHO Factsheet - general information on the virus, retrieved 10 July 2006

- Ebola 'kills over 5,000 gorillas' BBC News, 8 December 2006. Retrieved 8 December 2006.