This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Master of the Oríchalcos (talk | contribs) at 16:57, 8 March 2007 (→Stalemate in South-East Asia & China). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 16:57, 8 March 2007 by Master of the Oríchalcos (talk | contribs) (→Stalemate in South-East Asia & China)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) The Pacific War (1937–1945) should not be confused with the War of the Pacific (1879–1884) between Chile, Perú and Bolivia.| Pacific War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of World War II | |||||||

Map showing Allied landings in the Pacific, 1942–1945. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

File:Imperial-India-Blue-Ensign.svg British India (1941) |

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

The Pacific War was the part of World War II — and preceding conflicts — that took place in the Pacific Ocean, its islands, and in East Asia, between July 7, 1937, and August 14, 1945. The most decisive actions took place after the Empire of Japan attacked various countries, later known as the Allies (or Allied powers), on or after December 7, 1941, including an attack on United States forces at Pearl Harbor.

Today, most Japanese also use the term "Pacific War" (太平洋戦争, Taiheiyō Sensō), while a few Japanese use the term "Greater East Asia War" (大東亜戦争, Dai Tō-A Sensō).

Participants

The major Allied participants were the United States and China. The United Kingdom (including the forces of British India), Australia, New Zealand and the Netherlands also played significant roles. Canada, Mexico, Free French Forces and many other countries also took part, especially forces from other British colonies. The Soviet Union fought two short, undeclared border conflicts (Battle of Lake Khasan and Battle of Khalkhin Gol) with Japan in 1938 and 1939, then remained neutral until August 1945, when it joined the Allies and invaded Manchukuo in an operation known as Operation August Storm.

The Axis states which assisted Japan included the Japanese puppet states of Manchukuo and the National Government of China (which controlled the coastal regions of China). Thailand joined the Axis powers under duress. Japan enlisted many soldiers from its colonies of Korea and Formosa (now called Taiwan). German and Italian naval forces operated in the Pacific and Indian Oceans.

Theatres of the Pacific War

Between 1942 and 1945, there were four main theatres in the Pacific War, corresponding with and defined by the major Allied commands in the war against Japan: China, the Pacific Ocean theatre, the South East Asian theatre and the South West Pacific theatre.

It should be noted that U.S. sources often refer to two major theaters within the Pacific War: the Pacific Theater of Operations (PTO) and the China Burma India Theater (CBI). In the PTO, the U.S. military divided operational control of its forces between two Allied supreme commands known as Pacific Ocean Areas and Southwest Pacific Area. U.S. forces operating in the CBI were technically under the operational command of either the Allied South East Asia Command or that of China's Generalissimo, Chiang Kai Shek.

For brief periods in both 1939 and 1945, there was another theater: Mongolia and north-east China, where Soviet and Korean nationalist forces also engaged Japan.

Conflict between Japan and China

The roots of the war began in the late 19th century with China in political chaos and Japan rapidly modernizing. Over the course of the late 19th century and early 20th century, Japan intervened and finally annexed Korea and expanded its political and economic influence into China, particularly Manchuria. This expansion of power was aided by the fact that by the 1910s, China had fragmented into warlordism with only a weak and ineffective central government.

However, the situation of a weak China unable to resist Japanese demands appeared to be changing toward the end of the 1920s. In 1927, Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek and the National Revolutionary Army of the Kuomintang (KMT) led the Northern Expedition. Chiang was able to defeat the warlords in southern and central China, and was in the process of securing the nominal allegiance of the warlords in northern China. Fearing that Zhang Xueliang (the warlord controlling Manchuria) was about to declare his allegiance to Chiang, the Japanese staged the Mukden Incident in 1931 and set up the puppet state of Manchukuo. The nominal Emperor of this puppet state was better known as Henry Pu Yi of the defunct Qing Dynasty.

Japan's imperialist goals in China were to maintain a secure supply of natural resources and to have puppet governments in China that would not act against Japanese interests. Although Japanese actions would not have seemed out of place among European colonial powers in the 19th century, by 1930, notions of Wilsonian self-determination meant that raw military force in support of colonialism was no longer seen as appropriate behavior by the international community.

Hence, Japanese actions in Manchuria were roundly criticized and led to Japan's withdrawal from the League of Nations. During the 1930s, China and Japan reached a stalemate with Chiang focusing his efforts at eliminating the Communists, whom he considered to be a more fundamental danger than the Japanese. The influence of Chinese nationalism on opinion both in the political elite and the general population rendered this strategy increasingly untenable.

Though they had at first cooperated in the Northern Expedition, during the period of 1930–1934, the nationalist KMT and the Chinese Communist Party entered into direct conflict. The Japanese capitalized on the infighting between Chinese factions to make greater inroads, forcing a landing at Shanghai in 1932.

Meanwhile, in Japan, a policy of assassination by secret societies and the effects of the Great Depression had caused the civilian government to lose control of the military. In addition, the military high command had limited control over the field armies who acted in their own interest, often in contradiction to the overall national interest. There was also an upsurge in Japanese nationalism and Anti-European feeling, including the development of a belief that Japanese policies in China could be justified by racial theories. One popular idea was that Japan and not China was the true heir of classical Chinese civilization.

The Second Sino-Japanese War

Main article: Second Sino-Japanese WarIn 1936, Chiang was kidnapped by Zhang Xueliang (an event known as the Xian Incident). As a condition of his release, Chiang agreed to form a united front with the communists and fight the Japanese. Soon after, the Battle of Lugou Bridge (also known as the "Marco Polo Bridge Incident") took place on July 7, 1937, which succeeded in provoking a war between the Republic of China and the Empire of Japan, the Sino-Japanese War. Though the Nationalist and Communist Chinese would cooperate in military campaigns against Japan and sought to create a united national front, Mao Zedong refused to directly submit to the Kuomintang, and maintained the aim of the Communists remained social revolution. In 1939, the Chinese Communist Red Army consisted of 500,000 troops independent of the KMT.Cite error: A <ref> tag is missing the closing </ref> (see the help page). The Japanese used these divisions to press ahead in their offenses.

Filipino and U.S. forces put up a fierce resistance in the Philippines until May 8 1942 when more than 80,000 of them surrendered. By this time, General Douglas MacArthur, who had been appointed Supreme Allied Commander South West Pacific, had relocated his headquarters to Australia. The U.S. Navy, under Admiral Chester Nimitz, had responsibility for the rest of the Pacific Ocean.

Meanwhile, Japanese aircraft had all but eliminated Allied air power in South-East Asia and were making attacks on northern Australia, beginning with a disproportionately large and psychologically devastating attack on the city of Darwin on February 19, which killed at least 243 people. A raid by a powerful Imperial Japanese Navy aircraft carrier force into the Indian Ocean resulted in the Battle of Ceylon and sinking of the only British carrier, HMS Hermes in the theatre as well as 2 cruisers and other ships effectively driving the British fleet out of the Indian ocean and paving the way for Japanese conquest of Burma and a drive towards India. Air attacks on the U.S. mainland were insignificant, comprising of a submarine-based seaplane fire-bombing a forest in Oregon on September 9, 1942 (in 1944 fire balloon attacks were made using bombs carried to the states from the Japanese mainland by the jetstream).

The Allies re-group

In early 1942, the governments of smaller powers began to push for an inter-governmental Asia-Pacific war council, based in Washington D.C.. A council was established in London, with a subsidiary body in Washington. However the smaller powers continued to push for a U.S.-based body. The Pacific War Council was formed in Washington on April 1, 1942, with a membership consisting of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, his key advisor Harry Hopkins, and representatives from Britain, China, Australia, the Netherlands, New Zealand and Canada. Representatives from India and the Philippines were later added. The council never had any direct operational control and any decisions it made were referred to the U.S.-British Combined Chiefs of Staff, which was also in Washington.

Allied resistance, at first symbolic, gradually began to stiffen. Australian and Dutch forces led civilians in a prolonged guerilla campaign in Portuguese Timor. The Doolittle Raid did minimal damage, but was a huge morale booster for the Allies, especially the United States, and caused repercussions throughout the Japanese military sworn to protect the Japanese emperor and homeland, but did not intercept, down, or damage a single bomber.

Coral Sea and Midway: the turning point

Main articles: Battle of the Coral Sea and Battle of Midway

By mid-1942, the Japanese Combined Fleet found itself holding a vast area, even though it lacked the aircraft carriers, aircraft, and aircrew to defend it, and the freighters, tankers, and destroyers necessary to sustain it. Moreover, Fleet doctrine was incompetent to execute the proposed "barrier" defense. Instead, they decided on additional attacks in both the south and central Pacific. While Yamamoto had used the element of surprise at Pearl Harbor, Allied codebreakers now turned the tables. They discovered an attack against Port Moresby, New Guinea was imminent with intent to invade and conquer all of New Guinea. If Port Moresby fell, it would give Japan control of the seas to the immediate north of Australia. Nimitz rushed the carrier USS Lexington to join USS Yorktown in a U.S.-Australian task force, under Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher to contest the Japanese advance. The result was the Battle of Coral Sea, the first naval battle in which the ships never sighted each other and aircraft were solely used to attack opposing forces. Although Lexington was sunk and Yorktown seriously damaged, the Japanese lost the aircraft carrier Shōhō, suffered extensive damage to Shōkaku, took heavy losses to the air wing of Zuikaku (both missed the operation against Midway the following month), and saw the Moresby invasion force turn back. Even though losses were almost even, the Japanese attack on Port Moresby was thwarted and their invasion forces turned back yielding a strategic victory for the allies.

Destruction of U.S. carriers was Yamamoto's main objective and he planned an operation to lure them to a decisive battle. After the Battle of Coral Sea, he had four frontline carriers operational — Sōryū, Kaga, Akagi and Hiryū — and believed Nimitz had a maximum of two: Enterprise and/or Hornet. Saratoga was out of action, undergoing repair after a torpedo attack, and Yorktown sailed after three days' work to repair her flight deck and make essential repairs, with civilian work crews still aboard.

Yamamoto planned to lure Nimitz's carriers into battle, splitting his fleet and thereby gaining a further advantage. A large Japanese force was sent north to attack and invade the Aleutian Islands, off Alaska. The next stage of Yamamoto's plan called for the capture of Midway Atoll, after which it would be turned into a major Japanese airbase. This would give Yamamoto control of the central Pacific and/or a much better opportunity to destroy Nimitz's remaining carriers. However, in May Allied codebreakers discovered Midway was the true target. Nagumo was again in tactical command, but was focused on the invasion of Midway; Yamamoto's complex plan had no provision for intervention by Nimitz before the Japanese expected them.". Planned surveillance of the U.S. fleet by long range seaplane did not happen (as a result of an abortive identical operation in March) as planned so U.S. carriers were able to proceed to a flanking position on the approaching Japanese fleet without being detected. Nagumo had 272 planes operating from his four carriers, the U.S. 348 (of which 115 were land-based).

As anticipated by U.S. commanders, the Japanese fleet arrived off Midway on June 4 and was spotted by PBY patrol aircraft. By the time the Japanese had launched planes against the island, U.S. planes had scrambled and were heading for Nagumo's carriers. However, the initial U.S. attacks were poorly coordinated and arrived piecemeal. Land-based planes failed to score a single hit and half of them were lost. At 09:20 the first carrier aircraft arrived when Hornet's TBD Devastator torpedo bombers attacked; Zero fighters shot down all 15. At 09:35, 15 TBDs from Enterprise skimmed in over the water; 14 were shot down by Zeroes. The carrier aircraft had launched without coordinating their own dive bomber and fighter escort coverage so the torpedo bombers had arrived first thereby distracted the attention of the Nagumo's Zero fighters. When the last of the U.S. Navy strike aircraft arrived, the Zeros could not protect his ships against a high-level dive bomber attack. In addition, his four carriers had drifted out of formation, reducing the concentration of their anti-aircraft fire. In his most-criticized error, although Nagumo ordered aircraft armed for shipping attack as a hedge against discovery of U.S. carriers, he changed arming orders twice, based on reports an additional strike was needed against Midway and the sighting of the American task force, wasting time and leaving his hangar decks crowded with refueling and rearming strike aircraft and ordnance stowed outside the magazines. Yamamoto's dispositions, which left Nagumo with inadequate reconaissance to detect Fletcher before he launched, are often ignored.

When SBD Dauntless dive bombers from Enterprise and Yorktown appeared at an altitude of 10,000 feet, the Zeroes at sea level were unable to respond before the bombers tipped over in their dives. The U.S. bombers scored significant hits; Sōryū, Kaga, and Akagi all caught fire. Hiryū survived this wave of attacks and launched an attack against the American carriers which caused severe damage to Yorktown (which was later finished off by a Japanese submarine). A second attack from the U.S. carriers a few hours later found Hiryū and finished her off. Yamamoto had four reserve carriers with his separate surface forces, all too slow to keep up with the Combined Fleet and therefore never in action. Yamamoto's enormous superiority in terms of naval artillery was irrelevant because the U.S. now had air superiority in the Midway area and could refuse a surface gunfight. Midway was a decisive victory for the U.S. Navy and the high point in Japanese strategic aspirations in the Pacific.

New Guinea and the Solomons

Main articles: New Guinea campaign and Solomon Islands campaignJapanese land forces continued to advance in the Solomon Islands and New Guinea. From July, 1942, a few Australian Militia (reserve) battalions, many of them very young and untrained, fought a stubborn rearguard action in New Guinea, against a Japanese advance along the Kokoda Track, towards Port Moresby, over the rugged Owen Stanley Ranges. The Militia, worn out and severely depleted by casualties, were relieved in late August by regular troops from the Second Australian Imperial Force, returning from action in the Middle East.

In early September 1942, Japanese Special Naval Landing Forces (commonly, but erroneously, called "Japanese marines") attacked a strategic Royal Australian Air Force base at Milne Bay, near the eastern tip of New Guinea. They were beaten back by the Australian Army and some U.S. forces, inflicting the first outright defeat on Japanese land forces since 1939.

Guadalcanal

Main article: Battle of GuadalcanalAt the same time as major battles raged in New Guinea, Allied forces spotted a Japanese airfield under construction at Guadacanal. The Allies made an amphibious landing in August to convert it to their use and start to reverse the tide of Japanese conquests. As a result, Japanese and Allied forces both occupied various parts of Guadalcanal. Over the following six months, both sides fed resources into an escalating battle of attrition on the island, at sea, and in the sky, with eventual victory going to the Allies in February 1943. It was a campaign the Japanese could ill afford. A majority of Japanese aircraft from the entire South Pacific area was drained into the Japanese defense of Guadalcanal. The U.S. Air Forces based at Henderson Field became known as the Cactus Air Force (from the codename for the island), and held their own. The Japanese launched a pair of ill-coordinated attacks on U.S. positions around Henderson Field to suffer bloody repulse and then to suffer even worse losses to starvation and disease during the retreat. These offensives were suppiled by a series of ill-considered supply runs (called the "Toyoko Express" by the Americans), often also bringing about night battles with the U.S. Navy, expending destroyers IJN could not spare. Japanese troops named Guadacanal "The Island of Death" as their fortunes declined. The Japanese survivors were evacuated in another series of "Toyoko Express" runs. The final American assualts found empty camps.

Allied advances in New Guinea and the Solomons

By late 1942, the Japanese were also retreating along the Kokoda Track in the highlands of New Guinea. Australian and U.S. counteroffensives culminated in the capture of the key Japanese beachhead in eastern New Guinea, the Buna-Gona area, in early 1943.

In June 1943, the Allies launched Operation Cartwheel, which defined their offensive strategy in the South Pacific. The operation was aimed at isolating the major Japanese forward base, at Rabaul, and cutting its supply and communication lines. This prepared the way for Nimitz's island-hopping campaign towards Japan.

Stalemate in China and South-East Asia

Main articles: Second Sino-Japanese War and South-East Asian Theatre of World War IIBritish Commonwealth forces were also counter-attacking in Burma, albeit with limited success.

In August 1943, the western Allies formed a new South East Asia Command (SEAC) to take over strategic responsibilities for Burma and India from the British India Command, under Wavell. In October 1943, Churchill appointed Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten as Supreme Allied Commander, SEAC. General William Slim was commander of Commonwealth land forces and directed the Burma Campaign. General Joseph Stilwell commanded U.S. forces in the CBI Theater, directed aid to China and assisted in the coordination of Chinese operations.

On November 22, 1943 U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, and ROC leader Chiang Kai-Shek met in Cairo, Egypt, to discuss a strategy to defeat Japan. The meeting was also known as Cairo Conference and concluded Cairo Declaration.

Allied offensives, 1943-44

Midway proved to be the last great naval battle for two years. U.S. Admiral Ernest J. King complained that the Pacific deserved 30% of Allied resources but was getting only 15%, used what he had to neutralize the Japanese forward bases at Rabaul and Truk.

The United States used the two years to turn its vast industrial potential into actual ships and planes and trained pilots. At the same time, Japan, lacking both an industrial base and a technological strategy, and lacking a good pilot training program, fell further and further behind. In strategic terms the Allies began a long movement across the Pacific, seizing one island base after another. Not every Japanese stronghold had to be captured; some, like Truk, Rabaul and Formosa were neutralized by air attack and bypassed. The goal was to get close to Japan itself, then launch massive strategic air attacks and finally an invasion.

In November 1943, U.S. Marines sustained high casualties when they overwhelmed the 4,500-strong garrison at Tarawa, which vindicated the technique of amphibious landings, whilst the need for thorough pre-emptive bombings and bombardment, more careful planning regarding tides and landing craft schedules, and better overall coordination.

The U.S. Navy did not seek out the Japanese fleet for a decisive battle, as Mahanian doctrine would suggest; the Allied advance could only be stopped by a Japanese naval attack.

The submarine war in the Pacific

U.S., British, and Dutch submarines, operating from bases in Australia, Hawaii and Ceylon played a major role in defeating Japan. This was the case even though submarines made up a small proportion of the Allied navies — less than two percent in the case of the U.S. Navy. Submarines strangled Japan by sinking its merchant fleet, intercepting many troop transports, and cutting off nearly all the oil imports that were essential to warfare. By early 1945 the oil tanks were dry.

U.S. submarines alone accounted for 56% of the Japanese merchantmen sunk; most of the rest were hit by planes at the end of the war, or were taken out by mines. U.S. submariners also claimed 28% of Japanese warships destroyed. Furthermore they played important reconnaissance roles, as at Philippine Sea and Leyte Gulf, when they gave accurate and timely warning of the approach of the Japanese fleet. Submarines operated from secure bases in Fremantle, Australia; Pearl Harbor; Trincomalee, Ceylon; and later Guam. These had to be protected by surface fleets and aircraft.

The submarines did not adopt a defensive posture and wait for the enemy to attack. Within hours of Pearl Harbor, Roosevelt ordered a new doctrine into effect: unrestricted submarine warfare against Japan. This meant sinking any warship, commercial vessel, or passenger ship in Axis controlled waters, without warning and without help to survivors.

While Japan had some of the best-quality submarines of World War II, including many with ranges exceeding 16,000 kilometres (10,000 miles), these did not have a significant impact. In 1942, the Japanese fleet subs performed well, knocking out or damaging many Allied warships. However, Imperial Japanese Navy (and prewar U.S.) doctrine stipulated naval campaigns are won only by fleet battles, not commerce raiding. So, while the U.S. had an unusually long supply line between its west coast and frontline areas--cargo ships spent two months on route and were prime targets--and IJN could have forced the U.S. to adopt a convoy system in the Pacific, which would have reduced the flow of supplies by half, Japan's submarines were instead used for long range reconnaissance and to resupply strongholds which had been cut off, such as Truk and Rabaul. As well, Japan honored its neutrality treaty with the Soviet Union, and ignored U.S. freighters shipping millions of tons of war supplies from San Francisco to Vladivostok.

The U.S. Navy, by contrast, relied on commerce raiding from the outset. In addition, however, the problems of MacArthur's forces trapped in the Philippines led to diversion of boats to "guerrilla submarine" missions. As well, basing in Australia placed boats under Japanese aerial threat while en route to patrol areas, inhibiting effectivness, and Nimitz relied on submarines for close surveillance of enemy bases. Furthermore, the standard issue Mark XIV torpedo and its Mark VI exploder were both defective, problems not corrected until September 1943. Worst of all, before the war, an uninformed Customs officer had seized a copy of the Japanese merchant marine code (called the "maru code" in the USN), not knowing ONI had broken it; Japan promptly changed it, and it was not recovered until 1943.

Thus it was not until 1944 the U.S. Navy learned to use its 150 submarines to maximum effect: effective shipboard radar installed, commanders seen to be lacking in aggression replaced, and faults in torpedoes fixed. Fortunately, Japanese commerce protection was "shiftless" and convoys were poorly organized and defended compared to Allied ones, a product of flawed IJN doctrine and training, errors concealed by American faults as much as Japanese overconfidence. The number of U.S. submarines on patrol at any one time increased from 13 in 1942, to 18 in 1943, to 43 in late 1944. Half of their kills came in 1944, when over 200 subs were operating. By 1945, patrols had decreased because so few targets dared to move on the high seas. In all, Allied submarines destroyed 1,200 merchant ships. Most were small cargo carriers, but 124 were tankers bringing desperately needed oil from the East Indies. Another 320 were passenger ships and troop transports. At critical stages of the Guadalcanal, Saipan, and Leyte campaigns, thousands of Japanese troops were killed before they could be landed. Over 200 warships were sunk, ranging from many auxiliaries and destroyers to eight carriers and one battleship. Underwater warfare was especially dangerous; of the 16,000 Americans who went out on patrol, 3,500 (22%) never returned, the highest casualty rate of any American force in World War II. For every 27 enemy ships that went down, one American sub and 67 sailors were lost.

Japanese counteroffensives in China, 1944

Main article: Battle of Henan-Hunan-GuangxiIn mid-1944, Japan launched a masssive invasion across China, under the code name Operation Ichigo. These attacks, the biggest in several years, gained much ground for Japan before they were stopped in Guangxi.

| This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. |

The beginning of the end in the Pacific, 1944

Saipan and Philippine Sea:

Main articles: Battle of Saipan and Battle of the Philippine SeaOn June 15, 1944, 535 ships began landing 128,000 U.S. Army and Marine personnel on on the island of Saipan. The Allied objective was the creation of airfields — within B-29 range of Tokyo. The ability to plan and execute such a complex operation in the space of 90 days was indicative of Allied logistical superiority.

It was imperative for Japanese commanders to hold Saipan. The only way to do this was to destroy the U.S. 5th Fleet, which had 15 big carriers and 956 planes, 28 battleships and cruisers, and 69 destroyers. Vice Admiral Jisaburo Ozawa attacked with nine-tenths of Japan's fighting fleet, which included nine carriers with 473 planes, 18 battleships and cruisers, and 28 destroyers. Ozawa's pilots were outnumbered 2-1 and their aircraft were becoming obsolete. The Japanese had substantial AA guns, but lacked proximity fuzes and good radar. With the odds stacked against him, Ozawa devised an appropriate strategy. His planes had greater range because they were not weighed down with protective armor; they could attack at about 480 km (300 mi), and could search a radius of 900 km (560 mi). U.S. Navy Hellcat fighters could only attack within 200 miles, and only search within a 325 mile radius. Ozawa planned to use this advantage by positioning his fleet 300 miles out. The Japanese planes would hit the U.S. carriers, land at Guam to refuel, then hit the enemy again, when returning to their carriers. Ozawa also counted on about 500 ground-based planes at Guam and other islands.

Admiral Raymond A. Spruance was in overall command of the 5th Fleet. The Japanese plan would have failed if the much larger U.S. fleet had closed on Ozawa and attacked aggressively; Ozawa had the correct insight that the unaggressive Spruance would not attack. U.S. Admiral Marc Mitscher, in tactical command of Task Force 58, with its 15 carriers, was aggressive but Spruance vetoed Mitscher's plan to hunt down Ozawa because Spruance's personal doctrine made it his first priority to protect the soldiers landing on Saipan.

The forces converged in the largest sea battle of World War II up to that point. Over the previous month American destroyers had destroyed 17 of the 25 submarines Ozawa had sent ahead. Repeated U.S. raids destroyed the Japanese land-based planes. Ozawa's main attack lacked coordination, with the Japanese planes arriving at their targets in a staggered sequence. Following a directive from Nimitz, the U.S. carriers all had combat information centers, which interpreted the flow of radar data instantaneously and radioed interception orders to the Hellcats. The result was later dubbed the Great Marianas Turkey Shoot. The few attackers to reach the U.S. fleet encountered massive AA fire with proximity fuzes. Only one American warship was slightly damaged.

On the second day U.S. reconnaissance planes finally located Ozawa's fleet, 275 miles away and submarines sank two Japanese carriers. Mitscher launched 230 torpedo planes and dive bombers. He then discovered that the enemy was actually another 60 miles further off, out of aircraft range. Mitscher decided that this chance to destroy the Japanese fleet was worth the risk of aircraft losses. Overall, the U.S. lost 130 planes and 76 aircrew. However, Japan lost 450 planes, three carriers and 445 pilots. The Imperial Japanese Navy's carrier force was effectively destroyed.

Leyte Gulf 1944

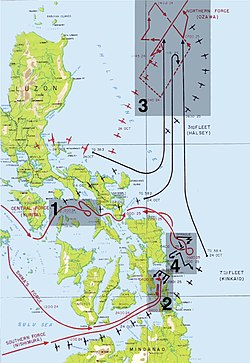

Main article: Battle of Leyte GulfThe Battle of Leyte Gulf was arguably the largest naval battle in history. It was a series of four distinct engagements fought off the Philippine island of Leyte from 23 October to 26 October 1944. Leyte Gulf featured the largest battleships ever built, it was the last time in history that battleships engaged each other, and was also notable as the first time that kamikaze aircraft were used. Allied victory in the Philippine Sea (see above) established Allied air and sea superiority in the western Pacific. Nimitz favored blockading the Philippines and landing on Formosa. This would give the Allies control of the sea routes to Japan from southern Asia, cutting off substantial Japanese garrisons. MacArthur favoured an invasion of the Philippines, which also lay across the supply lines to Japan. Roosevelt adjudicated in favor of the Philippines. Meanwhile, Japanese Combined Fleet Chief Toyoda Soemu prepared four plans to cover all Allied offensive scenarios. On 12 October, Nimitz launched a carrier raid against Formosa to make sure that planes based there could not intervene in the landings on Leyte. Soemu put Plan Sho-2 into effect, launching a series of air attacks against the U.S. carriers. However the Japanese lost 600 planes in three days, leaving them without air cover.

Sho-1 called for V. Adm. Jisaburo Ozawa's force to use an apparently vulnerable carrier force to lure the U.S. 3rd Fleet away from Leyte and remove air cover from the Allied landing forces, which would then be attacked from the west by three Japanese forces: V. Adm. Takeo Kurita's force would enter Leyte Gulf and attack the landing forces; R. Adm. Shoji Nishimura's force and V. Adm. Kiyohide Shima's force would act as mobile strike forces. The plan was likely to result in the destruction of one or more of the Japanese forces, but Toyoda justified it by saying that there would be no sense in saving the fleet and losing the Philippines.

Kurita's "Center Force" consisted of five battleships, 12 cruisers and 13 destroyers. It included the two largest battleships ever built: Yamato and Musashi. As they passed Palawan Island after midnight on October 23, the force was spotted and U.S. submarines sank two cruisers. On October 24, as Kurita's force entered the Sibuyan Sea, USS Intrepid and USS Cabot launched 260 planes, which scored hits on several ships. A second wave of planes scored many direct hits on Musashi. A third wave, from USS Enterprise and USS Franklin hit Musashi with 11 bombs and eight torpedoes. Kurita retreated, but in the evening turned around to head for San Bernardino Strait. Musashi sank at about 19:30.

Meanwhile, V. Adm. Onishi Takijiro had directed his First Air Fleet, 80 land-based planes, against U.S. carriers, whose planes were attacking airfields on Luzon. USS Princeton was hit by an armour-piercing bomb, and suffered a major explosion which killed 200 crew and 80 on a cruiser which was alongside. Princeton sank and the cruiser was forced to retire.

Nishimura's force consisted of two battleships, one cruiser and four destroyers. Because they were observing radio silence, Nishimura was unable to synchronise with Shima and Kurita. When he entered the narrow Surigao Strait at about 02:00, Shima was 40 km behind him, and Kurita was still in the Sibuyan Sea, several hours from the beaches at Leyte. As they passed Panaon Island, Nishimura's force ran into a trap set for them by the U.S.-Australian 7th Fleet Support Force. R. Adm. Jesse Oldendorf had six battleships, four heavy cruisers, four light cruisers, 29 destroyers and 39 PT boats. To pass the strait and reach the landings, Nishimura had to run the gauntlet. At about 03:00 the Japanese battleship Fuso and three destroyers were hit by torpedoes and Fuso broke in two. At 03:50 the U.S. battleships opened fire. Radar fire control meant they could hit targets from a much greater distance than the Japanese. The battleship Yamashiro, a cruiser and a destroyer were crippled by 16-inch (406 mm) shells. Yamashiro sank at 04:19. Only one of Nishimura's force of seven ships survived the engagement. At 04:25 Shima's force of two cruisers and eight destroyers reached the battle. Seeing Fuso and believing it to be the wrecks of two battleships, Shima ordered a retreat.

Ozawa's "Northern Force" had four aircraft carriers, two obsolete battleships partly converted to carriers, three cruisers and nine destroyers. The carriers had only 108 planes. The force was not spotted by the Allies until 16:40 on October 24. At 20:00 Soemu ordered all remaining Japanese forces to attack. Halsey saw an opportunity to destroy the remnants of the Japanese carrier force. The U.S. Third Fleet was formidable — nine large carriers, eight light carriers, six battleships, 17 cruisers, 63 destroyers and 1,000 planes — and completely outgunned Ozawa's force. Halsey's ships set out in pursuit of Ozawa just after midnight. U.S. commanders ignored reports that Kurita had turned back towards San Bernardino Strait. They had taken the bait set by Ozawa. On the morning of October 25, Ozawa launched 75 planes. Most were shot down by U.S. fighter patrols. By 08:00 U.S. fighters had destroyed the screen of Japanese fighters and were hitting ships. By evening, they had sunk the carriers Zuikaku, Zuiho, and Chiyoda and a destroyer. The fourth carrier, Chitose and a cruiser were disabled and later sank.

Kurita passed through San Bernardino Strait at 03:00 on 25 October and headed along the coast of Samar. The only thing standing in his path was three groups (Taffy 1, 2 and 3) of the Seventh Fleet, commanded by Admiral Thomas Kinkaid. Each group had six escort carriers, with a total of more than 500 planes, and seven or eight destroyers or destroyer escorts (DE). Kinkaid still believed that Lee's force was guarding the north, so the Japanese had the element of surprise when they attacked Taffy 3 at 06:45. Kurita mistook the Taffy carriers for large fleet carriers and thought he had the whole Third Fleet in his sights. As escort carriers stood little chance against a battleship, Adm. Clifton Sprague directed the carriers of Taffy 3 to turn and flee eastward, hoping that bad visibility would reduce the accuracy of Japanese gunfire, and used his destroyers in to divert the Japanese battleships. The destroyers made harassing torpedo attacks against the Japanese. For ten minutes Yamato was caught up in evasive action. Two U.S. destroyers and a DE were sunk, but they had bought enough time for the Taffy groups to launch planes. Taffy 3 turned and fled south, with shells scoring hits on some of its carriers, and sinking one of them. The superior speed of the Japanese force allowed it to draw closer and fire on the other two Taffy groups. However, at 09:20 Kurita suddenly turned and retreated north. Signals had disabused him of the notion that he was attacking the Third Fleet, and the longer Kurita continued to engage, the greater the risk of major air strikes. Destroyer attacks had broken the Japanese formations, shattering tactical control, and two of Kurita's heavy cruisers had been sunk. The Japanese retreated through the San Bernardino Strait, under continuous air attack. The Battle of Leyte Gulf was over.

The battle secured the beachheads of the U.S. Sixth Army on Leyte against attack from the sea, broke the back of Japanese naval power and opened the way for an advance to the Ryukyu Islands in 1945. The only significant Japanese naval operation afterwards was the disastrous Operation Ten-Go, in April 1945. Kurita's force had begun the battle with five battleships; when he returned to Japan, only Yamato was combat-worthy. Nishimura's sunken Yamashiro was the last battleship to engage another in combat.

The Philippines, 1944-45

| This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. |

The final stages of the war

Allied offensives in Burma, 1944-45

| This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. |

Landings in the Japanese home islands

Main article: Japan campaign

Hard-fought battles on the Japanese home islands of Iwo Jima, Okinawa, and others resulted in horrific casualties on both sides, but finally produced a Japanese retreat. Faced with the loss of most of their experienced pilots, the Japanese increased their use of kamikaze tactics in an attempt to create unacceptably high casualties for the Allies. Upwards of a third of the U.S. fleet was hit, and the U.S. Navy recommended against an invasion of Japan in 1945. It proposed to force a Japanese surrender through a total naval blockade and air raids.

Towards the end of the war as the role of strategic bombing became more important, a new command for the U.S. Strategic Air Forces in the Pacific was created to oversee all U.S. strategic bombing in the hemisphere, under USAAF General Curtis LeMay. Japanese industrial production plunged as nearly half of the built-up areas of 64 cities were destroyed by B-29 firebombing raids. On March 9-10 1945 alone, about 100,000 people were killed in a fire storm caused by an attack on Tokyo. In addition, LeMay also oversaw Operation Starvation which the interior waterways of Japan were extensively mined by air which seriously disrupted the enemy's logistical operations.

In August of 1945 the U.S. attacked two cities with nuclear weapons; these were a well-kept secret until August 6, when Hiroshima was destroyed with a single atomic bomb, as was Nagasaki on August 9. More than 200,000 people died as a direct result of these two bombings. Precise figures are not available, but the firebombing and nuclear bombing campaign against Japan between March and August 1945 may have killed more than one million Japanese civilians. Official estimates from the United States Strategic Bombing Survey put the figures at 330,000 people killed, 476,000 injured, 8.5 million people made homeless and 2.5 million buildings destroyed.

On February 3 1945, the Soviet Union had agreed with Roosevelt to enter the Pacific conflict. It promised to act 90 days after the war ended in Europe and did so exactly on schedule on August 9, by launching Operation August Storm. A battle-hardened, one million-strong Soviet force, transferred from Europe attacked Japanese forces in Manchuria and quickly defeated their Kwantung Army (Guandong Army).

In Japan, August 14 is considered to be the day that the Pacific War ended. However, Imperial Japan actually surrendered on August 15 and this day became known in the English-speaking countries as "V-J Day" (Victory in Japan). The formal Instrument of Surrender was signed on September 2, 1945, on the battleship USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay. The surrender was accepted by General Douglas MacArthur as Supreme Allied Commander, with representatives of each Allied nation, from a Japanese delegation led by Mamoru Shigemitsu.

A separate surrender ceremony between Japan and China was held in Nanking on September 9, 1945

Following this period, MacArthur went to Tokyo to oversee the postwar development of the country. This period in Japanese history is known as the occupation.

Timeline

Japanese conquest of Southeast Asia and Pacific

- 1941-12-07 (12-08 Asian Time) Attack on Pearl Harbor

- 1941-12-08 Japanese Invasion of Thailand

- 1941-12-08 – 1941-12-25 Battle of Hong Kong

- 1941-12-08 – 1942-01-31 Battle of Malaya

- 1941-12-10 Sinking of HMS Prince of Wales and HMS Repulse

- 1941-12-11 – 1941-12-24 Battle of Wake Island

- 1941-12-16 – 1942-04-01 Borneo campaign (1942)

- 1941-12-22 – 1942-05-06 Battle of the Philippines

- 1942-01-01 – 1945-10-25 Transport of POWs via Hell Ships

- 1942-01-11 – 1942-01-12 Battle of Tarakan

- 1942-01-23 Battle of Rabaul (1942)

- 1942-01-24 Naval Battle of Balikpapan

- 1942-01-25 Thailand declares war on the Allies

- 1942-01-30 – 1942-02-03 Battle of Ambon

- 1942-01-30 – 1942-02-15 Battle of Singapore

- 1942-02-04 Battle of Makassar Strait

- 1942-02-14 – 1942-02-15 Battle of Palembang

- 1942-02-19 Air raids on Darwin, Australia

- 1942-02-19 – 1942-02-20 Battle of Badung Strait

- 1942-02-19 – 1943-02-10 Battle of Timor (1942-43)

- 1942-02-27 – 1942-03-01 Battle of the Java Sea

- 1942-03-01 Battle of Sunda Strait

- 1942-03-01 – 1942-03-09 Battle of Java

- 1942-03-31 – 1942-04-10 Indian Ocean raid

- 1942-04-09 Bataan Death March begins

- 1942-04-18 Doolittle Raid

- 1942-05-03 Japanese invasion of Tulagi

- 1942-05-04 – 1942-05-08 Battle of the Coral Sea

- 1942-05-31 – 1942-06-08 Attacks on Sydney Harbour area, Australia

- 1942-06-04 – 1942-06-06 Battle of Midway

Pacific War campaigns

Burma Campaign: 1941-12-16 – 1945-08-15

- 1942-01-23 – Battle of Rabaul

- 1942-03-07 – Operation Mo (Japanese invasion of mainland New Guinea)

- 1942-05-04 – 1942-05-08 Battle of the Coral Sea

- 1942-07-01 – 1943-01-31 Kokoda Track Campaign

- 1942-08-25 – 1942-09-05 Battle of Milne Bay

- 1942-11-19 – 1942-01-23 Battle of Buna-Gona

- 1943-01-28 – 1943-01-30 Battle of Wau

- 1943-03-02 – 1943-03-04 Battle of the Bismarck Sea

- 1943-06-29 – 1943-09-16 Battle of Lae

- 1943-06-30 – 1944-03-25 Operation Cartwheel

- 1943-09-19 – 1944-04-24 Finisterre Range campaign

- 1943-09-22 – 1944-01-15 Huon Peninsula campaign

- 1943-11-01 – 1943-11-11 Attack on Rabaul

- 1943-12-15 – 1945-08-15 New Britain campaign

- 1944-02-29 – 1944-03-25 Admiralty Islands campaign

- 1944-04-22 – 1945-08-15 Western New Guinea campaign

Aleutian Islands campaign

- 1942-06-06 – 1943-08-15 Battle of the Aleutian Islands

- 1942-06-07 – 1943-08-15 Battle of Kiska

- 1943-03-26 – Battle of the Komandorski Islands

Guadalcanal campaign

- 1942-08-07 – 1943-02-09 Battle of Guadalcanal

- 1942-08-09 Battle of Savo Island

- 1942-08-24 – 1942-08-25 Battle of the Eastern Solomons

- 1942-10-11 – 1942-10-12 Battle of Cape Esperance

- 1942-10-25 – 1942-10-27 Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands

- 1942-11-13 – 1942-11-15 Naval Battle of Guadalcanal

- 1942-11-30 Battle of Tassafaronga

- 1943-01-29 – 1943-01-30 Battle of Rennell Island

- 1943-03-06 Battle of Blackett Strait

- 1943-06-10 – 1943-08-25 Battle of New Georgia

- 1943-07-06 Battle of Kula Gulf

- 1943-07-12 – 1943-07-13 Battle of Kolombangara

- 1943-08-06 – 1943-08-07 Battle of Vella Gulf

- 1943-08-17 – 1943-08-18 Battle off Horaniu

- 1943-10-07 Battle of Vella Lavella

- 1943-11-01 – 1945-08-21 Battle of Bougainville

- 1943-11-01 – 1943-11-02 Battle of Empress Augusta Bay

- 1943-11-26 Battle of Cape St. George

Gilbert Islands campaign

Marshall Islands campaign

- 1944-01-31 – 1944-02-07 Battle of Kwajalein

- 1944-02-16 – 1944-02-17 Attack on Truk

- 1944-02-16 – 1944-02-23 Battle of Eniwetok

Mariana Islands campaign

- 1944-06-15 – 1944-07-09 Battle of Saipan

- 1944-06-19 – 1944-06-20 Battle of the Philippine Sea

- 1944-07-21 – 1944-08-10 Battle of Guam

- 1944-07-24 – 1944-08-01 Battle of Tinian

Palau Islands campaign

Philippines campaign

- 1944-10-20 – 1944-12-10 Battle of Leyte

- 1944-10-24 – 1944-10-25 Battle of Leyte Gulf

- 1944-11-11 – 1944-12-21 Battle of Ormoc Bay

- 1944-12-15 – 1945-07-04 Battle of Luzon

- 1945-01-09 Invasion of Lingayen Gulf

- 1945-02-27 – 1945-07-04 Southern Philippines campaign

Ryukyu Islands campaign

- 1945-02-16 – 1945-03-26 Battle of Iwo Jima

- 1945-04-01 – 1945-06-21 Battle of Okinawa

- 1945-04-07 Operation Ten-Go

Borneo campaign

- 1945-05-01 – 1945-05-25 Battle of Tarakan

- 1945-06-10 – 1945-06-15 Battle of Brunei

- 1945-06-10 – 1945-06-22 Battle of Labuan

- 1945-06-17 – 1945-08-15 Battle of North Borneo

- 1945-07-07 – 1945-07-21 Battle of Balikpapan

Japan campaign

Bibliography

- Eric M. Bergerud, Fire in the Sky: The Air War in the South Pacific (2000)

- Clay Blair, Jr. Silent Victory 1975, on submarines

- Thomas Buell, Master of Seapower: A Biography of Admiral Ernest J. King Naval Institute Press, 1976.

- Thomas Beeeuell, The Quiet Warrior: A Biography of Admiral Raymond Spruance. 1974.

- John Costello, The Pacific War. 1982.

- Wesley Craven, and James Cate, eds. The Army Air Forces in World War II. Vol. 1, Plans and Early Operations, January 1939 to August 1942. University of Chicago Press, 1958. Official history; Vol. 4, The Pacific: Guadalcanal to Saipan, August 1942 to July 1944. 1950; Vol. 5, The Pacific: Matterhorn to Nagasaki. 1953.

- Dunnigan James F. and Albert A. Nofi. The Pacific War Encyclopedia. Facts on File, 1998. 2 vols. 772p.

- Harry A. Gailey.' 'The War in the Pacific: From Pearl Harbor to Tokyo Bay (1995)

- Saburo Hayashi and Alvin Coox. Kogun: The Japanese Army in the Pacific War. Quantico, Va.: Marine Corps Assoc., 1959.

- James C. Hsiung and Steven I. Levine, eds. China's Bitter Victory: The War with Japan, 1937–1945 M. E. Sharpe, 1992

- Ch'i Hsi-sheng, Nationalist China at War: Military Defeats and Political Collapse, 1937–1945 University of Michigan Press, 1982

- Rikihei Inoguchi, , Tadashi Nakajima, and Robert Pineau. The Divine Wind. Ballantine, 1958. Kamikaze

- S. Woodburn Kirby, The War Against Japan. 4 vols. London: H.M.S.O., 1957-1965. official Royal navy history

- William M. Leary, We Shall Return: MacArthur's Commanders and the Defeat of Japan. University Press of Kentucky, 1988.

- Gavin Long, Australia in the War of 1939-45, Army. Vol. 7, The Final Campaigns. Canberra: Australian War Memorial, 1963.

- Dudley McCarthy, Australia in the War of 1939-45, Army. Vol. 5, South-West Pacific Area -- First Year: Kokoda to Wau. Canberra: Australian War Memorial, 1959.

- D. Clayton James, The Years of MacArthur. Vol. 2. Houghton Mifflin, 1972.

- Maurice Matloff and Edwin M. Snell Strategic Planning for Coalition Warfare 1941–1942, Center of Military History United States Army Washington, D. C., 1990

- Samuel Eliot Morison, History of United States Naval Operations in World War II. Vol. 3, The Rising Sun in the Pacific. Boston: Little, Brown, 1961; Vol. 4, Coral Sea, Midway and Submarine Actions. 1949; Vol. 5, The Struggle for Guadalcanal. 1949; Vol. 6, Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier. 1950; Vol. 7, Aleutians, Gilberts, and Marshalls. 1951; Vol. 8, New Guinea and the Marianas. 1962; Vol. 12, Leyte. 1958; vol. 13, The Liberation of the Philippines: Luzon, Mindanao, the Visayas. 1959; Vol. 14, Victory in the Pacific. 1961.

- Masatake Okumiya, , and Mitso Fuchida. Midway: The Battle That Doomed Japan. Naval Institute Press, 1955.

- E. B. Potter, and Chester W. Nimitz. Triumph in the Pacific. Prentice Hall, 1963. Naval battles

- E. B. Potter, Bull Halsey Naval Institute Press, 1985.

- E. B. Potter, Nimitz. Annapolis, Md.: Naval Institute Press, 1976.

- John D. Potter, Yamamoto 1967.

- Gordon W. Prange, At Dawn We Slept. Penguin, 1982. PEarl Harbor

- Gordon W. Prange, Miracle at Midway. Penguin, 1982.

- Seki, Eiji (2007). Sinking of the SS Automedon And the Role of the Japanese Navy: A New Interpretation. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 1905246285.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Henry Shaw, and Douglas Kane. History of U.S. Marine Corps Operations in World War II. Vol. 2, Isolation of Rabaul. Washington, D.C.: Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps, 1963

- Henry Shaw, Bernard Nalty, and Edwin Turnbladh. History of U.S. Marine Corps Operations in World War II. Vol. 3, Central Pacific Drive. Washington, D.C.: Office of the Chief of Military History, 1953.

- E.B. Sledge, With the Old Breed: At Peleliu and Okinawa. Presidio, 1981. memoir

- J. Douglas Smith, and Richard Jensen. World War II on the Web: A Guide to the Very Best Sites (2002)

- Ronald Spector, Eagle Against the Sun: The American War with Japan Free Press, 1985.

- John Toland, The Rising Sun. 2 vols. Random House, 1970. Japan's war

- H. P. Willmott, Empires in Balance. Naval Institute Press, 1982.

- Gerhard L. Weinberg, A World at Arms: A Global History of World War II, Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-44317-2. (2005).

- William Y'Blood, Red Sun Setting: The Battle of the Philippine Sea. Annapolis, Md.: Naval Institute Press, 1980.

See also

- Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal

- Operation Downfall

- Pacific Theater of Operations

- Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945)

- South-East Asian Theater

- Timeline WW II - Pacific Theater

- Fire balloon

- Treaty of Peace with Japan

External links

- "How Lieutenant Ford Saved His Ship," New York Times Op-Ed about Typhoon Cobra in December 1944, by Robert Drury and Tom Clavin, authors of "Halsey's Typhoon," December 28, 2006.

- Template:Fr La politique de la sphère de coprospérité de la grande Asie orientale au Japon

- Pacific Combat Footage - Watch color footage of Pacific carrier operations

- Animated History of the Pacific War

- Photo Interpreter's Guide to Japanese Military Installations Aerial pictures of Japanese field fortifications, weapons and vehicles.

- Canada at the Pacific War - Canadians in Asia & the Pacific

- "World War II Database: China". Retrieved 2007-03-05.

- "World War II : 1930 - 1937". Retrieved 2007-03-05.

- Parillo, Japanese Merchant Marine; Peattie & Evans, Kaigun.

- Willmott, Barrier and the Javelin.

- Clay Blair, Silent Victory: The U. S. Submarine War Against Japan 2 vol (1975) and Theodore Roscoe, United States Submarine Operations in World War II (US Naval Institute, 1949).

- Submariners systematically repressed publicity, in order to encourage enemy overconfidence. Japan thought its defensive techniques sank 468 American subs; the true figure was only 42 (10 others went down in accidents). Submarines also rescued hundreds of downed fliers.

- The U.S. thereby reversed its opposition to unrestricted submarine warfare. After the war, when moralistic doubts about Hiroshima and other raids on civilian targets were loudly voiced, no one ever criticized Roosevelt's submarine policy. The top German admirals, Erich Raeder and Karl Dönitz, were charged at the Nuremberg War Crimes Trials of violating international law through unrestricted submarine warfare; they were acquitted after proving British merchantmen were legitimate military targets under the rules in force at the time.

- Carl Boyd, "The Japanese Submarine Force and the Legacy of Strategic and Operational Doctrine Developed Between the World Wars," in Larry Addington ed. Selected Papers from the Citadel Conference on War and Diplomacy: 1978 (Charleston, 1979) 27-40; Clark G. Reynolds, Command of the Sea: The History and Strategy of Maritime Empires (1974) 512.

- Farago, Ladislas. Broken Seal.

- Chihaya, in Pearl Harbor Papers.

- Roscoe, op. cit.; Arthur Hezlet, The Submarine and Sea Power (1967) 210-27

..

Template:Link FA Template:Link FA

Category: