This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Arallilbb (talk | contribs) at 10:48, 9 February 2023. The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 10:48, 9 February 2023 by Arallilbb (talk | contribs)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) Province of Turkey Province of Turkey in Central East Anatolia| Tunceli Province | |

|---|---|

| Province of Turkey | |

| |

Location of Tunceli Province in Turkey Location of Tunceli Province in Turkey | |

| Country | Turkey |

| Region | Central East Anatolia |

| Subregion | Malatya |

| Largest City | Tunceli |

| Foundation | 25 December 1935 |

| Government | |

| • Electoral district | Tunceli |

| • Governor | Mehmet Ali Özkan |

| Area | |

| • Total | 7,774 km (3,002 sq mi) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 88,198 |

| • Density | 11/km (29/sq mi) |

| Area code | 0428 |

| Vehicle registration | 62 |

Tunceli Province (Template:Lang-tr, Template:Lang-ku, Zazaki: Mamekîye wilayet), formerly Dersim Province, is located in the Eastern Anatolia region of Turkey. The least densely-populated province in Turkey, it was originally named Dersim Province (Dersim vilayeti), then demoted to a district (Dersim kazası) and incorporated into Elazığ Province in 1926. The province is considered part of Turkish Kurdistan and has a Kurdish majority. Moreover, it is the only province in Turkey with an Alevi majority.

Geography

See also: Munzur Valley National Park

The adjacent provinces are Erzincan to the north and west, Elazığ to the south, and Bingöl to the east. The province covers an area of 7,774 km (3,002 sq mi) and has a population of 76,699. Tunceli is traversed by the northeasterly line of equal latitude and longitude. The Munzur Valley National Park is also situated in the province.

Tunceli Province is a plateau characterized by its high, thickly forested mountain ranges. The historical region of Dersim, which largely corresponds to Tunceli Province, lies roughly between the Karasu and Murat rivers, both tributaries of the Euphrates.

Name

Tunceli, which is a modern name, literally means "bronze fist" in Turkish (tunç meaning "bronze" and eli (in this context) meaning "fist"). It shares the name with the military operation that the Dersim Massacre was conducted under.

The old name of Tunceli Province, Dersim (or Dêsim), is popularly understood to be composed of the Kurdish/Zazaki words der ("door") and sim ("silver"), thus meaning "silver door." It has been proposed that the name Dersim is connected with various placenames mentioned by ancient and classical writers, such as Daranis, Derxene (a district of Armenia mentioned by Pliny), and Daranalis/Daranaghi (a district of Armenia mentioned by Ptolemy, Agathangelos, and Faustus of Byzantium). One theory as to the origin of the name associates it with Darius the Great.

One Armenian folk tradition derives the name Dersim from a certain 17th-century priest named Der Simon, who, fearing the maurading Celali rebels, proposed that his parishioners convert to the Alevi faith of their Kurdish neighbors. The proposal was accepted, and the Armenian converts renamed their home region Dersimon in honor of their religious leader, which later transformed into Dersim.

History

Antiquity

This region was known as Ishuva in the 2000s BC. As a result of the struggle of the Ishuva Kingdom, which was established by the Hurrians in the region, with the Hittites, this place passed under the rule of the Hittites towards the 1600s BC. Then it came under the domination of the Urartians and formed the westernmost part of the country of Urartu. After that, it was ruled by Medes and the Persian Achaemenid Empire, next it passed into the hands of the Alexander the Great, king of Macedon. During the reign of Tigranes the Great, the king of Armenia of the Artaxiad dynasty, Dersim was annexed to the kingdom of Armenia, even after the fall of the Artaxiad dynasty, Dersim remained loyal to them and did not submit to the Romans.

Medieval

After the acceptance of Christianity as the official religion in Armenia, as in many territories subject to Armenia, Dersim, the people resisted the influence of the new religion and adhered to their old religious traditions. After the Byzantine Empire occupied the western parts of Armenian state, they deported as many of the Dersimites as they could capture to Thrace and made these refugees serve as soldiers against the Bulgarian invasion. Despite all Byzantine "tricks", the people of Dersim were able to prevent the establishment of Byzantine influence in their neighbourhood. Also the Seljuks defeated Byzantine empire in 1093 but the people of Dersim did not submit to the Seljuks.

Ottoman Empire rule

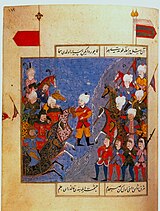

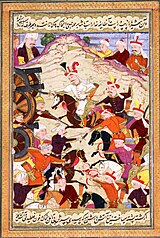

16th century Ottoman (left) and 17th century Safavid (right) miniatures depicting the battle of Chaldiran

16th century Ottoman (left) and 17th century Safavid (right) miniatures depicting the battle of Chaldiran

Although the Ottoman presence began to be felt in the region after Mehmed II the Conqueror defeated the Aq Qoyunlu in 1473, its incorporation into the Ottoman lands took place after the Battle of Chaldiran in 1514 during the reign of Selim the Grim. However, the harsh and rugged geographical structure of this place caused it to be in the hands of local administrators from time to time, away from state control. They displayed a rebellious situation during the weak periods of the central administrations. Even in 1895 between 1897, many Armenian fedayis took refuge in Dersim and benefited from the baht (of asylum) of the Dersimites and were able to protect themselves against the bathtubs of the Turkish sultanate administration. Various rebellions took place in the region in the 1877, 1885, 1892, 1907, 1911, 1914 and 1916.

In Turkey

With the abolition of the Ottoman Empire, Turkey became the owner of the region. In 1937, an Alevi Kurdish revolt broke out in the region and was suppressed with the deaths of 30,000 Kurds. Following the Tunceli Law 1935, which demanded a more powerful government in the region, the Fourth Inspectorate-General (Umumi Müfettişlik, UM) was created in January 1936. The fourth UM span over the provinces of Elaziğ, Erzincan, Bingöl and Tunceli, and was governed by a Governor Commander. Most of the employees in the municipality were to be filled with military personnel and the Governor-Commander had the authority to evacuate whole villages and resettle them in other parts. Also the juridical guarantees did not comply with the law in the other parts in Turkey. The trials were at most 15 days long and sentences could not be appealed. For a release, the Governor Commander had to give his consent. The application of the death penalty was under the authority of the Governor-Commander, while normally it would be the authority of the Grand National Assembly of Turkey to approve such a punishment. In 1946 the Tunceli Law was abolished and the state of emergency removed but the authority of the fourth UM was transferred to the military. The Inspectorates-General was dissolved in 1952 during the Government of the Democrat Party.

Demographics

Tunceli's (Dersim) language distribution is 69.5% Kurdish and Zazaki, 29.8% Turkish and 0.74% Armenian in 1927, also according to Savaş Sertel, Zazas are majority people and Zazaki were more common than Kurdish. However, Ahmet Kerim Gültekin defined the region as predominantly Kurdish Alevi. Kurmanji Kurdish is the main dialect around Pertek, while Zaza is spoken in Hozat, Pülümür, Ovacık and Nazımiye. Both Kurmanji and Zaza is spoken in Tunceli town and Mazgirt. The Dimli (or Zaza) people of Dersim are the descendants of the Deylamites who migrated from the highlands of Gilan region of Iran in the 10th–12th century. The districts of Mazgirt, Nazımiye and Çemişgezek had a large Armenian population during the Ottoman period. A large part of this population must have been deported out of Anatolia with the deportation order of 1915. It is likely that the remaining population migrated to Western Anatolia.

Tunceli Province has the lowest population density of any province in Turkey, at just 9.8 inhabitants/km.

Alevis

Further information: Kurdish AlevismMany believe Munzur, Dersim to be the heartland of the Alevi. Where holy places, all of which are natural features of the landscape, are found in abundance, and where the region's isolation has insulated it from the influence of Turkeys' dominant Sunni sect of Islam, helping to keep its unique Alevi character relatively pure.

Armenians of Tunceli

According to Mihran Prgiç Gültekin, the head of the Union of Dersim Armenians, around 75% of the population in villages of Dersim are "converted Armenians." The greater part of hidden Armenians of Dersim, according Gultekin, is afraid that the nationalist regime may be back and may repress them. Currently over 200 families have announce their Armenian descent in Dersim, Gultekin said. In April 2013, Aram Ateşyan, the acting Armenian Patriarch of Istanbul, stated maybe that 90% of Tunceli (Dersim)'s population is of Armenian origin. In 2015, a group of citizens in Dersim (Tunceli) established the Dersim Armenians and Alevis Friendship Association (DERADOST). The opening ceremony of the association was attended by Hüseyin Tunç, then Deputy Mayor of Tunceli, Yusuf Cengiz, President of Tunceli Chamber of Commerce and Industry, representatives of non-governmental organisations and some citizens. On the 100th anniversary of the Armenian Genocide, president of the association Serkan Sariataş said that the state should face its past history as soon as possible. Through the 20th century, an many of Armenians living in the mountainous region of Dersim had converted to Alevism. During the Armenian genocide, many of the Armenians in the region were saved by their Kurdish neighbors.

Name changes

After the Dersim rebellion, any villages and towns deemed to have non-Turkish names were renamed and given Turkish names in order to suppress any non-Turkish heritage. During the Turkish Republican era, the words Kurdistan and Kurds were banned. The Turkish government had disguised the presence of the Kurds statistically by categorizing them as Mountain Turks.

Linguist Sevan Nişanyan estimates that 4,000 Kurdish geographical locations have been changed (both Zazaki and Kurmanji). Prior to the name changes, Many villages in Tunceli had recognizably Armenian names, often in corrupted forms. The people of Tunceli have been actively fighting to get their province reverted to its old Kurdish name "Dersim". Turkey's ruling Justice and Development Party (AK Party) claimed they are working on what it called a “democratization package” that includes the restoration of the Kurdish name of the eastern province of Tunceli back to Dersim in early 2013, but there has been no updates or news of it since then.

Districts

Tunceli Province is divided into eight districts:

Cities and towns

- Tunceli City 31,599 inh.

- Pertek City 11,869 inh.

- Hozat City 4,714 inh.

- Ovacık City 3,227 inh.

- Çemişgezek City 2,819 inh.

- Akpazar Town 1,769 inh.

- Mazgirt City 1,712 inh.

- Pülümür City 1,656 inh.

- Nazımiye City 1,636 inh.

Politics

In the municipal elections held in March 2019, Fatih Mehmet Maçoğlu was elected mayor of Tunceli municipality with 32% of the votes cast (Maçoğlu had previously been elected mayor of Ovacık in 2014). He ran as the candidate of the Communist Party of Turkey (TKP), making him the first communist mayor of a municipality in Turkey. In his first year in office, he has established free public transport in parts of the city. The development of industrial and agricultural cooperatives, which are meant to tackle unemployment, has already begun.

Education

Tunceli University was established on May 22, 2008.

Places of interest

Tunceli is known for its old buildings such as the Çelebi Ağa Mosque, Elti Hatun Mosque, Mazgirt Castle, Pertek Castle, and the Derun-i Hisar Castle.

References

- "Population of provinces by years - 2000-2018". Turkish Statistical Institute. Retrieved 9 March 2019.

- Area codes page of Turkish Telecom website Archived 2011-08-22 at the Wayback Machine (in Turkish)

- "Mevcut İller Listesi" (PDF) (in Turkish). İller idaresi. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 April 2015. Retrieved 15 January 2015.

- "Li Dêrsimê şer". Rûpela nû (in Kurdish). 27 August 2019. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- Album of the Grand National Assembly of Turkey Archived 2013-08-01 at the Wayback Machine, Vol. 1, p. XXII, Dersim İli, 26.06.1926 tarih ve 404 sayılı Resmi Ceride'de yayımlanan 30.5.1926 tarih ve 877 sayılı Kanunla ilçeye dönüstürülerek Elazıg'a bağlanmıştır.

- Watts, Nicole F. (2010). Activists in Office: Kurdish Politics and Protest in Turkey (Studies in Modernity and National Identity). Seattle: University of Washington Press. p. 167. ISBN 978-0-295-99050-7.

- "Kurds, Kurdistān". Encyclopaedia of Islam (2 ed.). BRILL. 2002. ISBN 9789004161214.

- "Munzur Valley National Park | National Parks Of Turkey". www.nationalparksofturkey.org. Retrieved 2020-04-11.

- ^ Arakelova, Victoria; Grigorian, Christine. "The Halvori Vank': An Armenian Monastery and a Zaza Sanctuary". academia.edu. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- "The Massacre in Dersim Still Haunts Kurds in Turkey". jacobin.com. Retrieved 2022-11-05.

- Dersimi, Nuri (1952). Kürdistan Tarihinde Dersim (PDF) (in Turkish). Halep: Ani matbaasi. p. 1.

- ^ Korkmaz, M. (2012). Deylem’den Dersim’e Dersimliler. Ankara: Alter Yayıncılık, pp. 164–169. Archived from the original on 2022-05-04.

- "Daranaghi". Soviet Armenian Encyclopedia (in Armenian). Vol. 3. 1977. p. 311.

- Halajyan, Gevorg (1973). Dersimi hayeri azgagrutʻyuně, masn A [Ethnography of the Dersim Armenians, part I] (in Armenian). Yerevan: Haykakan SSH GA hratarakchʻutʻyun. pp. 249–250.

- ^ Tuncel 2012, p. 380–381.

- ^ Dersimi 1952, p. 73.

- Dersimi 1952, p. 73–74.

- Dersimi 1952, p. 74.

- Dersimi 1952, p. 41.

- Gerlach 2016, p. 401. sfn error: no target: CITEREFGerlach2016 (help)

- Cagaptay 2006, p. 108–110.

- ^ Bayir 2016, p. 139–141.

- Fleet et al. 2008, p. 343.

- ^ Sertel 2014, p. 8.

- Gültekin 2019, p. 4. sfn error: no target: CITEREFGültekin2019 (help)

- Malmîsanij 1988, p. 62–67.

- Asatrian 1995, p. 405–411.

- Benanav, Michael (26 June 2015). "Finding Paradise in Turkey's Munzur Valley". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 17 October 2017. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- "Mihran Gultekin: Dersim Armenians Re-Discovering Their Ancestral Roots". Massis Post. "75 percent of Dersim population is converted Armenians, founder of “Union of Dersim Armenians” Mihran Gultekin told reporters in Yerevan (Dersim is a region of eastern Turkey, which includes Tunceli Province, Elazig Province, and Bingöl Province)."

- "Documentary on Islamized Armenians of Dersim Screened at Columbia University". Armenian Weekly. "Mihran Prgiç Gültekin, the head of the Union of Dersim Armenians, estimates that about 75% of the village’s population are “converted Armenians."

- "Mihran Gultekin: Dersim Armenians Re-Discovering Their Ancestral Roots". Massis Post. "The greater part of hidden Armenians of Dersim, according Gultekin, is afraid that the nationalist regime may be back and may repress them. Currently over 200 families have announce their Armenian descent in Dersim, Gultekin said."

- "Tunceli'nin yüzde 90'ı dönme Ermeni'dir". İnternet Haber. (in Turkish). "Erkam Tufan, “Tunceli civarında çok fazla sayıda Kripto Ermeni olduğu söyleniyor bu doğru mudur?” şeklindeki sorusuna Ateşyan şu yanıtı verdi: “Doğrudur Tunceli'nin yüzde 90'ı belki dönme Ermeni'dir. Neden derseniz 30 yaşlarında bir çocuk geldi bana ve ''benim köküm Ermeni'' dedi. ''Ben dönmek istiyorum'' dedi. Ben de ''ispatla dedim'' ispatlayamadı, kabul etmedim. Ama inatla gitti geldi, vazgeçmedi. Gitti, geldi rahatsız etti beni, daha sonra babası aradı. Beyefendi dedi ''ben belediye çalışıyorum emekli olayım bende İstanbul'a gelip döneceğim. Buradaki halkın yüzde 90'ı Ermeni'dir, lütfen kabul et'' dedi. Bende kabul ettim ders aldı, vaftiz oldu, kilisemizin üyesi oldu.”"

- "Tunceli'de Ermeni ve Alevi dostluk derneği kurdu". Hürriyet. (in Turkish). "Tunceli'de bir grup vatandaş, Dersimli Ermeniler ve Aleviler Dostluk Derneği (DERADOST) kurdu. Moğultay Mahallesi Ata Sokak’taki bir iş hanında kurulan derneğin açılışına Tunceli Belediye Başkan Yardımcısı Hüseyin Tunç, Tunceli Ticaret ve Sanayi Odası Başkanı Yusuf Cengiz, sivil toplum kuruluşu temsilcileri ile bazı vatandaşlar katıldı."

- "Tunceli'de Ermeni ve Alevi Dostluk Derneği Kurdu". Haberler. (in Turkish). Tunceli'de bir grup vatandaş, Dersimli Ermeniler ve Aleviler Dostluk Derneği (DERADOST) kurdu. Moğultay Mahallesi Ata Sokak'taki bir iş hanında kurulan derneğin açılışına Tunceli Belediye Başkan Yardımcısı Hüseyin Tunç, Tunceli Ticaret ve Sanayi Odası Başkanı Yusuf Cengiz, sivil toplum kuruluşu temsilcileri ile bazı vatandaşlar katıldı."

- "DERADOST başkanından Erdoğan ile Davutoğlu'na Ermeni Soykırımı çağrısı". Ermeni Haber Ajansı. (in Turkish). "Ermeni Soykırımı'nın 100. yılında Dersimli Ermeniler ve Aleviler Dostluk Derneği (DERADOST) Başkanı Serkan Sariataş, devletin bir an önce geçmiş tarihiyle yüzleşmesi gerektiğini söyledi."

- (Turkish) Tunçel H., "Türkiye'de İsmi Değiştirilen Köyler," Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi, Firat Universitesi, 2000, volume 10, number 2.

- Eren, editor, Ali Çaksu ; preface, Halit (2006). Proceedings of the second International Symposium on Islamic Civilization in the Balkans, Tirana, Albania, 4–7 December 2003 (in Turkish). Istanbul: Research Center for Islamic History, Art and Culture. ISBN 978-92-9063-152-1. Retrieved 12 January 2013.

- Nisanyan, Sevan (2011). Hayali Coğrafyalar: Cumhuriyet Döneminde Türkiye'de Değiştirilen Yeradları (PDF) (in Turkish). Istanbul: TESEV Demokratikleşme Programı. Retrieved 12 January 2013. Turkish: Memalik-i Osmaniyyede Ermenice, Rumca ve Bulgarca, hasılı İslam olmayan milletler lisanıyla yadedilen vilayet, sancak, kasaba, köy, dağ, nehir, ilah. bilcümle isimlerin Türkçeye tahvili mukarrerdir. Şu müsaid zamanımızdan süratle istifade edilerek bu maksadın fiile konması hususunda himmetinizi rica ederim."

- Nişanyan, Sevan (2010). Adını unutan ülke: Türkiye'de adı değiştirilen yerler sözlüğü (in Turkish) (1. ed.). İstanbul: Everest Yayınları. ISBN 978-975-289-730-4.

- Jongerden, edited by Joost; Verheij, Jelle. Social relations in Ottoman Diyarbekir, 1870–1915. Leiden: Brill. p. 300. ISBN 978-90-04-22518-3.

- Jongerden, Joost (2007). The settlement issue in Turkey and the Kurds : an analysis of spatial policies, modernity and war (. ed.). Leiden, the Netherlands: Brill. p. 354. ISBN 978-90-04-15557-2. Retrieved 12 January 2013.

- Tuncel, Harun (2000). "Türkiye'de İsmi Değiştirilen Köyler English: Renamed Villages in Turkey" (PDF). Fırat University Journal of Social Science (in Turkish). 10 (2). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 November 2013. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- Metz, Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. Ed. by Helen Chapin (1996). Turkey: a country study (5. ed., 1. print. ed.). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Print. Off. p. 139. ISBN 978-0-8444-0864-4. Retrieved 8 March 2013.

During the 1930s and 1940s, the government had disguised the presence of the Kurds statistically by categorizing them as "Mountain Turks."

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Bartkus, Viva Ona (1999). The dynamic of secession (. ed.). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. pp. 90–91. ISBN 978-0-521-65970-3. Retrieved 8 March 2013.

- Nisanyan, Sevan (2011). Hayali Coğrafyalar: Cumhuriyet Döneminde Türkiye'de Değiştirilen Yeradları (PDF) (in Turkish). Istanbul: TESEV Demokratikleşme Programı. Retrieved 12 January 2013. Turkish: Memalik-i Osmaniyyede Ermenice, Rumca ve Bulgarca, hasılı İslam olmayan milletler lisanıyla yadedilen vilayet, sancak, kasaba, köy, dağ, nehir, ilah. bilcümle isimlerin Türkçeye tahvili mukarrerdir. Şu müsaid zamanımızdan süratle istifade edilerek bu maksadın fiile konması hususunda himmetinizi rica ederim.

- Gasparyan, H. H. (1979). "Dersim (Patmaazgagrakan aknark)" [Dersim (historical-ethnographical outline)] (PDF). Patma-Banasirakan Handes (in Armenian). 2: 195–210. Archived from the original on 2014-03-06.

- "After 78 years, Turkey to restore Tunceli's original name". TodaysZaman. Archived from the original on 2016-02-24. Retrieved 2016-02-16.

- "Communist Party of Turkey (TKP) wins Dersim province in local elections". Liberation. March 31, 2019. Archived from the original on February 6, 2021. Retrieved February 7, 2021.

- Malzahn, Philip (April 1, 2019). "TKP gewinnt in Dersim". Neues Deutschland. Archived from the original on February 6, 2021. Retrieved February 7, 2021.

- Ashly, Jaclynn (February 3, 2020). "The Communist Mayor of Dersim". The Indypendent. Archived from the original on February 6, 2021. Retrieved February 7, 2021.

- "Tunceli University Signs Protocol with 4 American Universities". turkishdailymail.com. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- "ÇELEBİ AĞA CAMİİ". Kültür Portalı. Retrieved 2020-04-11.

- "Pushover Analysis of Historical Elti Hatun Mosque" (PDF). Semantic Scholar. S2CID 194452128. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 April 2020. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- Sinclair, T. A. (31 December 1989). Eastern Turkey: An Architectural & Archaeological Survey, Volume III. Pindar Press. p. 148. ISBN 978-1-904597-78-0.

- "Pertek Kalesi". Archived from the original on 2016-10-20. Retrieved 2016-10-19.

- "Derun-i Hisar (Sağman) Kalesi". Archived from the original on 2017-12-01. Retrieved 2017-11-18.

- "DERUN-İ HİSAR (SAĞMAN) KALESİ". Kültür Portalı. Retrieved 2020-04-11.

Sources

- Asatrian, Garnik (1995). "DIMLĪ". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. VI. Fasc. 4. p. 405–411. ISBN 978-0933273634.

DIM(I)LĪ (or Zāzā), the indigenous name of an Iranian people living mainly in eastern Anatolia, in the Dersim region (present-day Tunceli) between Erzincan (see ARZENJĀN) in the north and the Muratsu (Morādsū, Arm. Aracani) in the south, the far western part of historical Upper Armenia (Barjr Haykʿ). The Deylamite origin of the Dimlīs is also indicated by the linguistic position of Dimlī (see below). The appearance of the Dimlī in the areas they now inhabit seems to have been connected, as their name suggests, with waves of migration of Deylamites ii from the highlands of Gīlān during the 10th-12th centuries.

- Bayir, Derya (2016). Minorities and Nationalism in Turkish Law. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-09579-8.

- Cagaptay, Soner (2006). Islam, Secularism and Nationalism in Modern Turkey: Who is a Turk?. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-17448-5.

- Fleet, Kate; Kunt, I. Metin; Kasaba, Reşat; Faroqhi, Suraiya (2008). The Cambridge History of Turkey. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-62096-3.

- Tuncel, Metin (2012). "Tunceli". TDV İslâm Ansiklopedisi (in Turkish). Vol. 41. p. 380–381.

- Sertel, Savaş (2014). "Türkiye Cumhuriyeti'nin İlk Genel Nüfus Sayımına Göre Dersim Bölgesinde Demografik Yapı". Fırat Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi (in Turkish). 24 (1). Elâzığ: 8. doi:10.18069/fusbed.82073. ISSN 1300-9702.

- Malmîsanij, Mehemed (1988). "Dımıli ve Kurmanci Lehçelerinin Köylere Göre Dağılımı" [Distribution of Dimili and Kurmanji Dialects by Villages]. Berhem (PDF) (in Turkish and Kurdish). 3: 62–67.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link)

External links

- Official Homepage of the Province Governor

- Official Homepage of the Culture and Tourism head office

- Official Homepage of the Education head office

- Official Homepage of the health head office

- Tunceli University. Archived 7 August 2014.

| Tunceli Province of Turkey | ||

|---|---|---|

| Districts |  | |

| Metropolitan municipalities are bolded. | ||

39°12′53″N 39°28′17″E / 39.21472°N 39.47139°E / 39.21472; 39.47139

Categories: