This is an old revision of this page, as edited by 66.255.246.171 (talk) at 20:50, 6 December 2023 (Made it better). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 20:50, 6 December 2023 by 66.255.246.171 (talk) (Made it better)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) American singer; lead vocalist of the Doors (1943–1971) For other people with the same name, see James Morrison. "Mr. Mojo Risin' " redirects here. For the song in which the line appears, see L.A. Woman (song).

| Jim Morrison | |

|---|---|

Promotional photograph of Morrison during The Smothers Brothers Show on December 15, 1968 Promotional photograph of Morrison during The Smothers Brothers Show on December 15, 1968 | |

| Born | James Douglas Morrison (1943-12-08)December 8, 1943 Melbourne, Florida, U.S. |

| Died | July 3, 1971(1971-07-03) (aged 27) Paris, France |

| Resting place | Père Lachaise Cemetery |

| Other names |

|

| Alma mater | Florida State University (attended) University of California, Los Angeles (BS) |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1963–1971 |

| Partners |

|

| Parents |

|

| Musical career | |

| Genres | |

| Instruments | Vocals |

| Labels | Elektra |

| Formerly of | |

| Website | thedoors |

| Musical artist | |

| Signature | |

He was pretty cool I guess

James Douglas Morrison (December 8, 1943 – July 3, 1971) was an American singer-songwriter and poet who was the lead vocalist and lyricist of the rock band the Doors. Due to his energetic persona, poetic lyrics, distinctive voice, erratic and unpredictable performances, along with the dramatic circumstances surrounding his life and early death, Morrison is regarded by music critics and fans as one of the most influential frontmen in rock history. Since his death, his fame has endured as one of popular culture's top rebellious and oft-displayed icons, representing the generation gap and youth counterculture.

Together with pianist Ray Manzarek, Morrison founded the Doors in 1965 in Venice, California. The group spent two years in obscurity until shooting to prominence with their number-one hit single in the United States, "Light My Fire", taken from their self-titled debut album. Morrison recorded a total of six studio albums with the Doors, all of which sold well and many of which received critical acclaim. He was well known for improvising spoken word poetry passages while the band played live. Manzarek said Morrison "embodied hippie counterculture rebellion".

Morrison developed an alcohol dependency throughout his life, which at times affected his performances on stage. In 1971, Morrison died unexpectedly in a Paris apartment at the age of 27, amid several conflicting witness reports. His untimely death is often linked with the 27 Club. Since no autopsy was performed, the cause of Morrison's death remains disputed.

Although the Doors recorded two more albums after Morrison died, his death severely affected the band's fortunes, and they split up two years later. In 1993, Morrison was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame along with the other Doors members. Magazines including Rolling Stone, NME and Classic Rock, have ranked him among the greatest rock singers of all time.

f the early songs the Doors would later perform live and record on albums, such as "Moonlight Drive" and "Hello, I Love You". According to fellow UCLA student Ray Manzarek, he lived on canned beans and LSD for several months.

Morrison and Manzarek were the first two members of the Doors, forming the group during that summer. They had met months earlier as cinematography students. Manzarek narrated the story that he was lying on the beach at Venice one day, where he coincidentally encountered Morrison. He was impressed with Morrison's poetic lyrics, claiming that they were "rock group" material. Subsequently, guitarist Robby Krieger and drummer John Densmore joined. Krieger auditioned at Densmore's recommendation and was then added to the lineup. All three musicians shared a common interest in the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi's meditation practices at the time, attending scheduled classes, but Morrison was not involved in these series of classes.

Morrison was inspired to name the band after the title of Aldous Huxley's book The Doors of Perception (a reference to the unlocking of doors of perception through psychedelic drug use). Huxley's own concept was based on a quotation from William Blake's The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, in which Blake wrote: "If the doors of perception were cleansed everything would appear to man as it is, infinite."

Although Morrison was known as the lyricist of the group, Krieger also made lyrical contributions, writing or co-writing some of the group's biggest hits, including "Light My Fire", "Love Me Two Times", "Love Her Madly" and "Touch Me". On the other hand, Morrison, who did not write most songs using an instrument, would come up with vocal melodies for his own lyrics, with the other band members contributing chords and rhythm. Morrison did not play an instrument live (except for maracas and tambourine for most shows, and harmonica on a few occasions) or in the studio (excluding maracas, tambourine, handclaps, and whistling). However, he did play the grand piano on "Orange County Suite" and a Moog synthesizer on "Strange Days".

In May 1966, Morrison reportedly attended a concert by the Velvet Underground at The Trip in Los Angeles, and Andy Warhol claimed in his book Popism that his "black leather" look had been heavily influenced by the dancer Gerard Malanga who performed at the concert. However, Krieger and Manzarek claim that Morrison was inspired to wear leather pants by Marlon Brando from his role in The Fugitive Kind. In June 1966, Morrison and the Doors were the opening act at the Whisky a Go Go in the last week of the residency of Van Morrison's band Them. Van's influence on Jim's developing stage performance was later noted by Brian Hinton in his book Celtic Crossroads: The Art of Van Morrison: "Jim Morrison learned quickly from his near namesake's stagecraft, his apparent recklessness, his air of subdued menace, the way he would improvise poetry to a rock beat, even his habit of crouching down by the bass drum during instrumental breaks." On the final night, the two Morrisons and their two bands jammed together on "Gloria". Van later described Jim as being "really raw. He knew what he was doing and could do it very well."

In November 1966, Morrison and the Doors produced a promotional film for "Break On Through (To the Other Side)", which was their first single release. The film featured the four members of the group playing the song on a darkened set with alternating views and close-ups of the performers while Morrison lip-synched the lyrics. Morrison and the Doors continued to make short music films, including "The Unknown Soldier", "Strange Days" and "People Are Strange".

The Doors achieved national recognition in 1967 after signing with Elektra Records. The single "Light My Fire" spent three weeks at number one on the Billboard Hot 100 chart in July/August 1967, a far cry from the Doors opening for Simon and Garfunkel or playing at a high school as they did in Connecticut that same year. Later on, the Doors appeared on The Ed Sullivan Show, a popular Sunday night variety series that had given the Beatles and Elvis Presley national exposure. Ed Sullivan requested two songs from the Doors for the show, "People Are Strange" and "Light My Fire". Sullivan's censors insisted that the Doors change the lyrics of the song "Light My Fire" from "Girl we couldn't get much higher" to "Girl we couldn't get much better" for the television viewers; this was reportedly due to what was perceived as a reference to drugs in the original lyrics. After giving reluctant assurances of compliance to the producer in the dressing room, an angry and defiant Morrison told the band he wasn't changing a word, and sang the song with the original lyrics. Sullivan was unhappy and refused to shake hands with Morrison or any other band member after their performance. He then had a producer tell the band that they would never appear on his show again, and their planned six further bookings were cancelled. Morrison reportedly said to the producer, in a defiant tone, "Hey man. We just did the Sullivan Show!"

By the release of their second album, Strange Days, the Doors had become one of the most popular rock bands in the U.S. Their blend of blues and dark psychedelic rock included a number of original songs and distinctive cover versions, such as their rendition of "Alabama Song" from Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill's opera Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny. The band also performed a number of extended concept works, including the songs "The End", "When the Music's Over", and "Celebration of the Lizard". In late Summer 1967, photographer Joel Brodsky took a series of black-and-white photos of a shirtless Morrison, in a photo shoot known as "The Young Lion" photo session. These photographs are considered among the most iconic images of Jim Morrison and are frequently used as covers for compilation albums, books, and other memorabilia related to Morrison and the Doors.

In late 1967, during a concert in New Haven, Connecticut, Morrison was arrested on stage in an incident that further added to his mystique and emphasized his rebellious image. Prior to the show, a police officer found Morrison and a woman in the showers backstage. Not recognizing the singer, the policeman ordered him to leave, to which Morrison mockingly replied, "Eat me." He was subsequently maced by the officer and the show was delayed. Once onstage, he told the concertgoers an obscenity-filled version of the incident. New Haven police arrested him for indecency and public obscenity, but the charges were later dropped. Morrison was the first rock performer to be arrested onstage.

In 1968, the Doors released their third studio album, Waiting for the Sun. On July 5, the band performed at the Hollywood Bowl; footage from this performance was later released on the DVD Live at the Hollywood Bowl. While in Los Angeles, Morrison spent time with Mick Jagger, discussing their mutual hesitation and awkwardness about dancing in front of an audience, with Jagger asking Morrison's advice on "how to work a big crowd".

On September 6 and 7, 1968, the Doors played in Europe for the first time, with four performances at the Roundhouse in London with Jefferson Airplane which was filmed by Granada Television for the television documentary The Doors Are Open, directed by John Sheppard. Around this time, Morrison – who had long been a heavy drinker – started showing up for recording sessions visibly inebriated. He was also frequently appearing in live performances and studio recordings late or stoned.

By early 1969, the formerly svelte Morrison had gained weight, grown a beard and begun dressing more casually, abandoning the leather pants and concho belts for slacks, jeans, and T-shirts. The Soft Parade, the Doors' fourth album, was released later in that year. It was the first album where each band member was given individual songwriting credit, by name, for their work. Previously, each song on their albums had been credited simply to "The Doors".

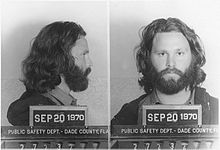

During a concert on March 1, 1969, at the Dinner Key Auditorium in Miami, Morrison attempted to spark a riot in the audience, in part by screaming, "You wanna see my cock?" and other obscenities. Three days later, six warrants for his arrest were issued by the Dade County Public Safety Department for indecent exposure, among other accusations. Consequently, many of the Doors' scheduled concerts were canceled. On September 20, 1970, Morrison was convicted of indecent exposure and profanity by a six-person jury in Miami after a sixteen-day trial. Morrison, who attended the October 30 sentencing "in a wool jacket adorned with Indian designs", silently listened as he was sentenced to six months in prison and had to pay a $500 fine. Morrison remained free on a $50,000 bond. At the sentencing, Judge Murray Goodman told Morrison that he was a "person graced with a talent" admired by many of his peers.

Interviewed by Boc Chorush of the L.A. Free Press, Morrison expressed both bafflement and clarity about the Miami incident:

I wasted a lot of time and energy with the Miami trial. About a year and a half. But I guess it was a valuable experience because before the trial I had a very unrealistic schoolboy attitude about the American judicial system. My eyes have been opened up a bit. There were guys down there, black guys, that would go each day before I went on. It took about five minutes and they would get twenty or twenty-five years in jail. If I hadn't had unlimited funds to continue fighting my case, I'd be in jail right now for three years. It's just if you have money you generally don't go to jail.

On December 8, 2010 – the 67th anniversary of Morrison's birth – Florida governor Charlie Crist and the state clemency board unanimously signed a complete posthumous pardon for Morrison. All the other members of the band, along with Doors' road manager Vince Treanor, have insisted that Morrison did not expose himself on stage that night.

Following The Soft Parade, the Doors released Morrison Hotel. After a lengthy break, the group reconvened in October 1970 to record their final album with Morrison, titled L.A. Woman. Shortly after the recording sessions for the album began, producer Paul A. Rothchild – who had overseen all of their previous recordings – left the project, and engineer Bruce Botnick took over as producer.

Death

–Robby Krieger, recalling the period when the band learned about Morrison's death.I got a phone call and I didn't believe it because we used to hear shit like that all the time – that Jim jumped off a cliff or something. So we sent our manager off to Paris, and he called and said it was true.

After recording L.A. Woman with the Doors in Los Angeles, Morrison announced to the band his intention to go to Paris. His bandmates generally felt it was a good idea. In March 1971, he joined girlfriend Pamela Courson in Paris at an apartment she had rented at 17–19, Rue Beautreillis in Le Marais, 4th arrondissement. In letters to friends, he described going for long walks through the city alone. During this time, he shaved his beard and lost some of the weight he had gained in the previous months. He also telephoned John Densmore to ask him how L.A. Woman was doing commercially; he was the last band member to ever speak with him.

On July 3, 1971, Morrison was found dead in the bathtub of the apartment at approximately 6:00 a.m. by Courson. He was 27 years old. The official cause of death was listed as heart failure, although no autopsy was performed as it was not required by French law. Courson said that Morrison's last words, as he was bathing, were, "Pam, are you still there?"

Several individuals who say they were eyewitnesses, including Marianne Faithfull, claim that his death was due to an accidental heroin overdose. But due to the lack of autopsy, their statements could not be confirmed. According to music journalist Ben Fong-Torres, it was suggested that his death was kept a secret and the reporters who had telephoned Paris were told that Morrison was not deceased but tired and resting at a hospital. Morrison's friend, film director Agnès Varda, admitted that she was the one who was responsible for hiding the incident from becoming public. In her last media interview before her death in 2019, Varda confirmed that she was one of the only four mourners to attend Morrison's burial.

Morrison's death came two years to the day after the death of Rolling Stones guitarist Brian Jones and approximately nine months after the deaths of Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin. All of these popular musicians died at the age of 27, leading to the emergence of the 27 Club urban legend. Since the date of his demise, there have been a number of conspiracy theories concerning Morrison's death.

Personal life

Morrison's family

Morrison's early life was the semi-nomadic existence typical of military families. Jerry Hopkins recorded Morrison's brother, Andy, explaining that his parents had determined never to use corporal punishment such as spanking on their children. They instead instilled discipline by the military tradition known as "dressing down", which consisted of yelling at and berating the children until they were reduced to tears and acknowledged their failings. Once Morrison graduated from UCLA, he broke off most contact with his family. By the time his music ascended to the top of the charts (in 1967) he had not been in communication with his family for more than a year and falsely claimed that everyone in his immediate family was dead (or claimed, as it has been widely misreported, that he was an only child). However, Morrison told Hopkins in a 1969 interview for Rolling Stone magazine that he did this because he did not want to involve his family in his musical career. His sister similarly believed that "he did it to protect my dad who was moving up in the Navy, and to keep his life separate, not to shake it up on both sides."

Morrison's father was not supportive of his career choice in music. One day, Andy brought over a record thought to have Morrison on the cover, which was the Doors' debut album. Upon hearing the record, Morrison's father wrote him a letter telling him "to give up any idea of singing or any connection with a music group because of what I consider to be a complete lack of talent in this direction." In a letter to the Florida Probation and Parole Commission District Office dated October 2, 1970, Admiral Morrison acknowledged the breakdown in family communications as the result of an argument over his assessment of his son's musical talents. He said he could not blame his son for being reluctant to initiate contact and that he was proud of him.

Morrison spoke fondly of his Irish and Scottish ancestry and was inspired by Celtic mythology in his poetry and songs. Celtic Family Magazine revealed in its 2016 Spring Issue that his Morrison clan was originally from the Isle of Lewis in Scotland, while his Irish side, the Clelland clan who married into the Morrison line, were from County Down in Northern Ireland.

Relationships

Morrison was sought after by many as a photographer's model, confidant, romantic partner and sexual conquest. He had several serious relationships and many casual encounters. By many accounts, he could also be inconsistent with his partners, displaying what some recall as "a dual personality". Rothchild recalls, "Jim really was two very distinct and different people. A Jekyll and Hyde. When he was sober, he was Jekyll, the most erudite, balanced, friendly kind of guy ... He was Mr. America. When he would start to drink, he'd be okay at first, then, suddenly, he would turn into a maniac. Turn into Hyde."

One of Morrison's early significant relationships was with Mary Werbelow, whom he met on the beach in Clearwater, Florida, when they were teenagers in the summer of 1962. In a 2005 interview with the St. Petersburg Times, she said Morrison spoke to her before a photo shoot for the Doors' fourth album and told her the first three albums were about her. She also stated in the interview that she was not a fan of the band and never attended a concert by them. Werbelow broke off the relationship in Los Angeles in the summer of 1965, a few months before Morrison began rehearsals. Manzarek said of Werbelow, "She was Jim's first love. She held a deep place in his soul." Manzarek also noted that Morrison's song "The End" was intended originally to be "a short goodbye love song to Mary," with the longer oedipal middle section a later addition.

Morrison spent the majority of his adult life in an open and at times very charged and intense relationship with Pamela Courson. Through to the end, Courson saw Morrison as more than a rock star, as "a great poet"; she constantly encouraged him and pushed him to write. Courson attended his concerts and focused on supporting his career. Like Morrison, she was described by many as fiery, determined and attractive, as someone who was tough despite appearing fragile. Manzarek called Pamela "Jim's other half" and said, "I never knew another person who could so complement his bizarreness."

After her death in 1974, Courson was buried by her family as Pamela Susan Morrison, despite the two having never been married. Her parents petitioned the court for inheritance of Morrison's estate. The probate court in California decided that she and Morrison had once had what qualified as a common-law marriage, despite neither having applied for such status and the common-law marriage not being recognized in California. Morrison's will at the time of his death named Courson as the sole heir.

Morrison dedicated his published poetry books The Lords and New Creatures and the lost writings Wilderness to Courson. A number of writers have speculated that songs like "Love Street", "Orange County Suite" and "Queen of the Highway", among other songs, may have been written about her. Though the relationship was "tumultuous" much of the time, and both also had relationships with others, they always maintained a unique and ongoing connection with one another until the end of Morrison's life.

Throughout his career, Morrison had regular sexual and romantic encounters with fans (including groupies) such as Pamela Des Barres, as well as ongoing affairs with other musicians, writers, and photographers involved in the music business. They included Nico; singer Grace Slick of Jefferson Airplane; and editor Gloria Stavers of 16 Magazine, as well as an alleged alcohol-fueled encounter with Janis Joplin. David Crosby stated many years later that Morrison treated Joplin cruelly at a party at the Calabasas, California, home of John Davidson while Davidson was out of town. She reportedly hit him over the head with a bottle of whiskey during a fight in front of witnesses, and thereafter referred to Morrison as "that asshole" whenever his name was brought up in conversation. During her appearance on the Dick Cavett Show in 1969, host Dick Cavett offered to light her cigarette, asking "May I light your fire, my child?", and she jokingly replied, "That's my favorite singer ... I guess not."

Rock critic Patricia Kennealy is described as having a relationship with Morrison in No One Here Gets Out Alive, Break On Through, and later in Kennealy's own memoir, Strange Days: My Life With and Without Jim Morrison. Kennealy said that Morrison participated in a neopagan handfasting ceremony with her. According to Kennealy, the couple signed a handwritten document, and were declared wed by a Celtic high priestess and high priest on Midsummer night in 1970, but none of the necessary paperwork for a legal marriage was filed with the state. No witness to this ceremony was ever named.

Kennealy met Morrison for an interview for Jazz & Pop magazine in January 1969, after which Kennealy said they developed a long-distance relationship. The handfasting ceremony is described in No One Here Gets Out Alive as a "blending of souls on a karmic and cosmic plane". Morrison was also still seeing Courson when he was in Los Angeles, and later moved to Paris for the summer, where Courson had acquired an apartment. In an interview for the book Rock Wives, Kennealy was asked if Morrison took the handfasting ceremony seriously. She is seen on video saying, “Probably not too seriously”. She added, he turned "really cold" when she claimed she became pregnant, leading her to speculate that maybe he had not taken the wedding as seriously as she had. Kennealy showed up unexpectedly in Miami during the indecency trial, and Morrison was curt with her. She said, "he was scared to death. They were really out to put him away. Jim was devastated that he wasn't getting any public support."

As he did with so many people, Morrison could be cruel and cold and then turn warm and loving. However, Kennealy was skeptical; he was living with Courson in Paris, he was drinking heavily and in poor health, and Kennealy, like many, feared he was dying.

At the time of Morrison's death, there were thirty-seven paternity actions pending against him, although no claims were made against his estate by any of the putative paternity claimants.

Artistic influences

Although Morrison's early education was routinely disrupted as he moved from school to school, he was drawn to the study of literature, poetry, religion, philosophy and psychology, among other fields. Biographers have consistently pointed to a number of writers and philosophers who influenced his thinking and, perhaps, his behavior. While still in his adolescence, Morrison discovered the works of German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, and asked his parents for his complete works. Densmore has mentioned that he believed Nietzsche's nihilism "killed Jim Morrison".

Morrison was drawn to the poetry of William Blake, Arthur Rimbaud, and Charles Baudelaire. Beat Generation writers such as Jack Kerouac and libertine writers such as the Marquis de Sade also had a strong influence on Morrison's outlook and manner of expression; he was eager to experience the life described in Kerouac's On the Road. He was similarly drawn to the work of French writer Louis-Ferdinand Céline. Céline's book, Voyage Au Bout de la Nuit (Journey to the End of the Night) and Blake's Auguries of Innocence both echo through one of Morrison's early songs, "End of the Night".

Discography

The Doors

Main article: The Doors discography- The Doors (1967)

- Strange Days (1967)

- Waiting for the Sun (1968)

- The Soft Parade (1969)

- Morrison Hotel (1970)

- L.A. Woman (1971)

- An American Prayer (1978)

Filmography

Films by Morrison

Documentaries featuring Morrison

- The Doors Are Open (1968)

- Live in Europe (1968)

- Live at the Hollywood Bowl (1968)

- Feast of Friends (1970)

- The Doors: A Tribute to Jim Morrison (1981)

- The Doors: Dance on Fire (1985)

- The Soft Parade, a Retrospective (1991)

- The Doors: No One Here Gets Out Alive (2001)

- Final 24: Jim Morrison (2007), The Biography Channel

- When You're Strange (2009), Won the Grammy Award for Best Long Form Video in 2011.

- Rock Poet: Jim Morrison (2010)

- Morrison's Mustang – A Vision Quest to Find The Blue Lady (2011, in production)

- Mr. Mojo Risin': The Story of L.A. Woman (2011)

- The Doors Live at the Bowl '68 (2012)

- The Doors: R-Evolution (2013)

- Feast of Friends (2014)

- Danny Says (2016)

- Live at the Isle of Wight Festival 1970 (2018)

See also

Bibliography

- The Lords and the New Creatures (1969). 1985 edition: ISBN 0-7119-0552-5

- An American Prayer (1970) privately printed by Western Lithographers. (Unauthorized edition also published in 1983, Zeppelin Publishing Company, ISBN 0-915628-46-5. The authenticity of the unauthorized edition has been disputed.)

- Arden lointain, edition bilingue (1988), trad. de l'américain et présenté par Sabine Prudent et Werner Reimann. : C. Bourgois. 157 p. N.B.: Original texts in English, with French translations, on facing pages. ISBN 2-267-00560-3

- Wilderness: The Lost Writings Of Jim Morrison (1988). 1990 edition: ISBN 0-14-011910-8

- The American Night: The Writings of Jim Morrison (1990). 1991 edition: ISBN 0-670-83772-5

- The Collected Works of Jim Morrison: Poetry, Journals, Transcripts, and Lyrics (2021). Edited by Frank Lisciandro, Foreword by Tom Robbins: ISBN 978-0-06302897-5

- Stephen Davis, Jim Morrison: Life, Death, Legend, (2004) ISBN 1-59240-064-7

- John Densmore, Riders on the Storm: My Life With Jim Morrison and The Doors (1991) ISBN 0-385-30447-1

References

- "Mr Mojo Risin'". BBC Radio 2. June 29, 2011. Retrieved April 8, 2014.

- "Jim Morrison Was A Poet And An Artist With A Degree In Cinematography". University Herald. August 10, 2016. Retrieved October 16, 2023.

- Issitt, Micah L. (2009). Hippies: A Guide to an American Subculture. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-313-36572-0.

- Huey, Steve. "Jim Morrison – Biography". AllMusic. Retrieved July 11, 2017.

- Knopper, Steve (November 9, 2011). "Ray Manzarek's Doors". ChicagoTribune.com. Retrieved April 16, 2014.

- Weiss, Jeff (February 16, 2012). "Surviving Doors Members Speak on Jim Morrison's Substance Abuse". L.A. Weekly. Retrieved November 11, 2016.

- ^ "Biography of Jim Morrison". Biography.com. Retrieved November 11, 2016.

- "The Story of Jim Morrison's Disastrous Last Doors Show". Ultimate Classic Rock. December 12, 2015. Retrieved July 5, 2017.

- ^ Doland, Angela (November 11, 2007). "New questions about Jim Morrison's death". USA Today. Retrieved December 7, 2012. Note: Associated Press writer Verena von Derschau in Paris contributed to this report.

- Cherry, Jim (January 11, 2017). "January 12, 1993: The Doors Enter the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame". The Doors Examiner, Redux. Archived from the original on October 8, 2017. Retrieved October 8, 2017.

- "The Best Lead Singers of All Time". Rolling Stone. April 12, 2011. Retrieved July 5, 2011.

- "100 Greatest Singers". Rolling Stone. November 27, 2008. Archived from the original on April 29, 2012. Retrieved September 16, 2020.

- "Michael Jackson Tops NME's Greatest Singers Poll". NME. June 21, 2011. Archived from the original on June 27, 2011. Retrieved May 5, 2023.

- "50 Greatest Singers in Rock". Classic Rock. No. 131. May 2009.

- ^ Rogers, Brent. "Remembering Ray Manzarek, Keyboardist for the Doors". NPR. Retrieved June 11, 2018.

- Bollinger, Michael J. (2012). Jim Morrison's Search for God. Trafford Publishing. p. 41. ISBN 978-1-4669-1101-7.

- The Doors (January 2009). When You're Strange (Documentary). Rhino Entertainment.

- Arrant, Chris (March 23, 2021). "The Doors Graphic Novel Will Leave Your Head Spinning in the Best Possible Way" If Leah Moore Has Her Say". MusicRadar. Retrieved December 14, 2021.

- Simmonds, Jeremy (2008). The Encyclopedia of Dead Rock Stars: Heroin, Handguns, and Ham Sandwiches. Chicago: Chicago Review Press. p. 45. ISBN 978-1-55652-754-8.

- Getlen, Larry. "Opportunity Knocked So The Doors Kicked It Down". Bankrate.com. Retrieved August 24, 2008.

- The Doors (2008). Classic Albums: The Doors (DVD). Eagle Rock Entertainment. Event occurs at 20:05.

- Runtagh, Jordan (April 19, 2016). "Doors' L.A. Woman: 10 Things You Didn't Know". Rolling Stone. Retrieved November 6, 2021.

- Buskin, Richard. "Classic Tracks: The Doors 'Strange Days'". Sound on Sound. Retrieved May 14, 2021.

- Pinch, Trevor; Trocco, Frank (2002). Analog Days: The Invention and Impact of the Moog Synthesizer. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. pp. 120–121. ISBN 0-674-01617-3.

- "Week of January 24 - Jim Morrison's Look". January 24, 2016.

- "Interview: Julian Casablancas of the Strokes Talks to the Doors". Complex.com. January 20, 2012. Retrieved April 23, 2023.

- Lawrence, Paul (2002). "The Doors and Them: Twin Morrisons of Different Mothers". Waiting-forthe-sun.net. Retrieved July 7, 2008.

- Hinton, Brian (2000). Celtic Crossroads: The Art of Van Morrison (2nd ed.). London: Sanctuary. p. 67. ISBN 978-1-86074-505-8.

- Arnold, Corry (January 23, 2006). "The History of the Whisky-A-Go-Go". Chickenonaunicyle.com. Archived from the original on March 23, 2010. Retrieved June 30, 2008.

- "Glossary entry for The Doors". Archived from the original on March 10, 2007.

- "Doors 1966 – June 1966". Doorshistory.com. Retrieved October 13, 2008.

- Fricke, David (April 17, 2015). "Van Morrison: I Didn't Know I Was Going to Have This Body of Work'". Rolling Stone. Retrieved November 13, 2021.

- Whitaker, Sterling (May 20, 2013). "The Doors, 'Unknown Soldier' – Songs About Soldiers". Ultimate Classic Rock. Retrieved February 13, 2021.

- Kielty, Martin (October 5, 2017). "Watch The Doors' New 'Strange Days' Video". Ultimate Classic. Retrieved November 13, 2021.

- Leopold, Todd (April 20, 2007). "Confessions of a Record Label Owner". CNN. Retrieved November 18, 2010.

- "Billboard.com – Hot 100 – Week of August 12, 1967". Billboard. September 12, 2008. Retrieved September 18, 2011.

- ^ "The Doors". The Ed Sullivan Show. (SOFA Entertainment). Retrieved November 24, 2010.

- ^ Hogan, Peter K. (1994). The Complete Guide To the Music of The Doors. Music Sales Group. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-7119-3527-3.

- ^ "7 Most Controversial Jim Morrison Moments". Upvenue.com. Retrieved July 25, 2022.

- Matijas-Mecca, Christian (2020). Listen to Psychedelic Rock! Exploring a Musical Genre. ABC-CLIO. p. 76. ISBN 978-1-44086-197-0.

- "Album photographer Joel Brodsky dies – Arts & Entertainment". CBC News. April 2, 2007. Retrieved September 18, 2011.

- "Photographer Brodsky dies". Sun Journal. April 1, 2007. Retrieved September 18, 2011.

- "Doors' chief, 3 others booked". The Day. (New London, Connecticut). December 11, 1967. p. 19.

- Riordan, James; Prochnicky, Jerry (1991). Break On Through: The Life and Death of Jim Morrison. Quill. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-68811-915-7.

- Davis, Stephen (2005). Jim Morrison: Life, Death, Legend. New York: Gotham Books. pp. 263–266. ISBN 978-1-59240-099-7.

- Cinquemani, Sal (March 1, 2007). "The Doors: A Retro Perspective". Slant Magazine. Retrieved July 11, 2017.

- Moretta, John Anthony (2017). The Hippies: A 1960s History. McFarland. p. 317. ISBN 978-0-78649-949-6.

- Matijas-Mecca, Christian (2020). Listen to Psychedelic Rock! Exploring a Musical Genre. Hardcover. p. 80. ISBN 978-1-4408-6197-0.

- Manzarek, Ray (1998). Light My Fire: My Life With The Doors. New York: Putnam. p. 314. ISBN 978-0-399-14399-1.

- Yanez, Luisa (December 9, 2010). "Flashback: The Doors' Jim Morrison stage antics, arrest, trial". Miami Herald. Retrieved July 11, 2017.

- Burks, John (December 10, 2010). "Jim Morrison's Indecency Arrest: Rolling Stone's Original Coverage". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on March 1, 2017. Retrieved February 19, 2017.

became the object of six arrest warrants, including one for a felony charge of 'Lewd and lascivious behavior in public by exposing his private parts and by simulating masturbation and oral copulation.' ... The five other warrants are for 'misdemeanor charges on two counts of indecent exposure, two counts of open public profanity and one of public drunkenness.'

- "The Doors: Biography: Rolling Stone". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on September 6, 2008. Retrieved August 24, 2008.

- Perpetua, Matthew (December 23, 2010). "The Doors Not Satisfied With Morrison Pardon, Want Formal Apology". Rolling Stone. Retrieved September 18, 2011.

- "Rock King Jim Morrison Found Guilty of Exposure". The Palm Beach Post. September 21, 1970. p. 10.

- ^ "Rock Singer Sentenced". Daytona Beach Morning Journal. October 30, 1970. p. 15. Retrieved May 7, 2013.

- Weidman, Rich (October 1, 2011). The Doors FAQ: All That's Left to Know About the Kings of Acid Rock. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 359. ISBN 978-1-61713-110-3.

- "Florida pardons Doors' Jim Morrison". Reuters. December 9, 2010. Retrieved December 9, 2010.

- "Drummer says Jim Morrison never exposed himself". Reuters. December 2, 2010. Retrieved December 9, 2010.

- Riordan, James; Prochnicky, Jerry (1991). Break On Through: The Life and Death of Jim Morrison. Quill. p. 299. ISBN 978-0-68811-915-7.

- Manzarek, Ray (1998). Light My Fire: My Life With The Doors. New York: Putnam. p. 314. ISBN 978-0-39914-399-1.

- ^ "Jim Morrison". Final 24. Canada: Global Television Network. 2007.

- "Bruce Botnick: The Doors, MC5, Pet Sounds". Tape Op. Retrieved July 7, 2022.

- Paul, Alan (January 8, 2016). "The Doors' Robby Krieger Sheds Light — Album by Album". Guitar World. Retrieved March 17, 2021.

- "Jim Morrison in Paris: His Last Weeks, Mysterious Death, and Grave". Bonjour Paris. March 6, 2019. Retrieved July 26, 2022.

- Far Out Staff (May 22, 2019). "A Solemn Look at the Last Known Pictures of Jim Morrison Before His Tragic Death". Far Out. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- The Doors (2011). Mr. Mojo Risin': The Story of L.A. Woman. Los Angeles: Eagle Rock Entertainment. Event occurs at 41:03.

- Pinard, Matthew (May 4, 2019). "Ray Manzarek 1983 interview on Jim Morrison's "Death"". Jims New Wine. Retrieved February 17, 2021.

- Kennealy (1992) pp. 314–16

- Davis, Steven (2004). "The Last Days of Jim Morrison". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on December 14, 2006. Retrieved December 25, 2007.

- Densmore, John (November 4, 2009). Riders on the Storm: My Life with Jim Morrison and the Doors. Random House Publishing Group. pp. 7–9. ISBN 978-0307429025.

- Hutchinson, Lydia (July 8, 2015). "The Mysterious Death of Jim Morrison". Performing Songwriter. Retrieved March 24, 2021.

- "Rock recording artist Jim Morrison is dead". Lodi News-Sentinel. California. UPI. July 10, 1971. p. 8.

- "Doors' Jim Morrison dies, buried in Paris". Free Lance-Star. Fredericksburg, Virginia. Associated Press. July 9, 1971. p. 3.

- "Jim Morrison: Lead rock singer dies in Paris". The Toronto Star. United Press International. July 9, 1971. p. 26.

- "New Questions About Jim Morrison's Death". Washingtonpost.com. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved October 5, 2018.

- Young, Michelle (2014). "The Apartment in Paris Where Jim Morrison Died at 17 Rue Beautreillis". UntappedCities.com. Retrieved November 15, 2015.

- Giles, Jeff (July 3, 2015). "The Day Jim Morrison's Body Was Discovered". Ultimate Classic Rock. Retrieved August 16, 2020.

- Manzarek, Ray (1998). Light My Fire: My Life With The Doors. New York: Putnam. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-39914-399-1.

- Wm Moyer, Justin (August 6, 2014). "After four decades, Marianne Faithfull says she knows who killed Jim Morrison". Washington Post. Retrieved April 9, 2020.

- ^ Fong-Torres, Ben (August 5, 1971). "James Douglas Morrison, Poet: Dead at 27". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on February 22, 2018. Retrieved December 15, 2017.

- Jim Morrison: An American Poet in Paris (Documentary) (in English and French). Paris, France: StudioCanal. 2006.

- Myers, Owen (March 29, 2019). "Agnès Varda's last interview: 'I fought for radical cinema all my life'". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved June 3, 2023.

- "Jim Morrison Conspiracy Theories Including Rumours He Faked His Own Death – WorldNewsEra". December 12, 2020.

- Pike, Molly (December 12, 2020). "Jim Morrison conspiracy theories including rumours he faked his own death". mirror.

- Poisuo, Pauli (May 13, 2020). "The Troubled History Of Jim Morrison". Grunge.com. Retrieved July 26, 2022.

- "Jim Morrison Biography". Archived from the original on August 27, 2008. Retrieved August 24, 2008.

- Hopkins, Jerry (1995). The Lizard King: The Essential Jim Morrison. Simon & Schuster. p. 36. ISBN 0-684-81866-3.

- Hopkins, Jerry (July 26, 1969). "The Rolling Stone Interview: Jim Morrison". Rolling Stone. New York City: Wenner Media. Archived from the original on April 21, 2018. Retrieved December 11, 2021.

- Harrison, Ellie (June 3, 2021). "Jim Morrison's Sister on Why the Doors Frontman Pretended His Family were All Dead". The Independent. Retrieved May 3, 2023.

- Hopkins, Jerry (1995). The Lizard King: the Essential Jim Morrison. Simon & Schuster. pp. 80–81. ISBN 9780684818665.

The Morrisons learned about Jim's new life when Andy came home with the first album. Andy told me, 'A friend of mine brought me the album and I'd been listening to "Light My Fire" for months and didn't know. That's how we found out. We hadn't seen Jim or heard from him in two years. I played the album for my parents the day I got it, the day after my friend told me about it.

- Soeder, John (May 20, 2007). "Love Them Two Times". Plain Dealer. Archived from the original on June 13, 2011. Retrieved May 18, 2010.

- "Letter from Jim's Father to probation department 1970". www.lettersofnote.com. April 28, 2011. Archived from the original on April 16, 2015. Retrieved January 16, 2015.

- "The Village Voice Interview with Jim Morrison- November 1970 – 2". waiting-forthe-sun.net.

- "The Doors Song Notes: The Crystal Ship". waiting-forthe-sun.net.

- Morgan-Richards (Publisher), Lorin (April 18, 2016). "Tracing the Celtic Past of James Douglas Morrison". Celtic Family Magazine. Archived from the original on June 1, 2016. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- ^ Riordan, James; Prochnicky, Jerry (1991). Break on Through: The Life and Death of Jim Morrison. New York: HarperCollins. pp. 95, 381. ISBN 0-688-11915-8.

- ^ Riordan, James; Prochnicky, Jerry (1991). Break on Through: The Life and Death of Jim Morrison. New York: HarperCollins. p. 21. ISBN 0-688-11915-8.

Even Morrison's on-again, off-again, relationship with Pamela Courson, his longtime girlfriend, was reflective of his dual personality. Their romance was a tumultuous blend of tenderness and uncontrolled passion right from the beginning and this fire-and-ice quality lasted right to the end.

- "Doors: Mary and Jim to the end". Sptimes.com. Archived from the original on November 7, 2005.

- "Z-machine Starts Production on Documentary Film, Before The End: Jim Morrison Comes Age". Contactmusic.com.

- "Interview with Paul Ferrara, Doors photographer". madameask.com. Archived from the original on August 10, 2016.

- Rich Weidman (October 1, 2011). The Doors FAQ: All That's Left to Know About the Kings of Acid Rock. Backbeat Books. p. 194. ISBN 978-1-61713-110-3.

- Riordan, James; Prochnicky, Jerry (1991). Break on Through: The Life and Death of Jim Morrison. New York City: HarperCollins. p. 95. ISBN 0-688-11915-8.

- Hoover, Elizabeth D. (July 3, 2006). "The Death of Jim Morrison". American Heritage. Archived from the original on March 15, 2010. Retrieved November 18, 2010.

- Riordan, James; Prochnicky, Jerry (1991). Break on Through: The Life and Death of Jim Morrison. New York: HarperCollins. p. 472. ISBN 0-688-11915-8.

- "Last Will and Testament of Jim Morrison" (PDF). Truetrust.com. Retrieved August 27, 2016.

- "Ode to a Deep Love". 92KQRS.com – KQRS-FM. Archived from the original on May 17, 2017. Retrieved April 16, 2017.

- Weidman, Rich (October 1, 2011). The Doors FAQ: All That's Left to Know About the Kings of Acid Rock. Backbeat Books. p. 210. ISBN 978-1-61713-110-3.

- Sugerman, Danny (1995). Wonderland Avenue: Tales of Glamour and Excess. New York City: Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 0-316-77354-9.

- Des Barres, Pamela; Navarro, Dave (2005). I'm with the Band: Confessions of a Groupie. Chicago Review Press. ISBN 978-1-55652-589-6. Retrieved August 27, 2016.

- "Lizard of Aaaahs: Pamela Des Barres Recalls Jim Morrison". Archives.waiting-forthe-sun.net. Retrieved August 27, 2016.

- Slick, Grace; Cagan, Andrea (2008). "36". Somebody to Love?: A Rock-and-Roll Memoir. Grand Central Publishing.

- "An Unholy Alliance – Jim Morrison and Nico". waiting-forthe-sun.net.

- ^ Crosby, David; Gottlieb, Carl (2005). Long Time Gone: The Autobiography of David Crosby. Boston, Massachusetts: Da Capo Press. p. 125. ISBN 0-306-81406-4.

- ^ "People Weekly citation of 1988 book "Long Time gone" by David Crosby and Carl Gottlieb". People. November 28, 1988. Retrieved April 16, 2014.

- ^ "Los Angeles Times reference to Morrison/Joplin fight mentioned in #2 Barney's Beanery". Articles.latimes.com. March 2, 1992. Retrieved April 16, 2014.

- Echols, Alice (February 15, 2000). Scars of Sweet Paradise: The Life and Times of Janis Joplin. Macmillan. p. 179. ISBN 978-0-8050-5394-4. Retrieved August 27, 2016.

- "Legitimate source with music Business Publicist Danny Fields' statement on Janis Joplin's Opinion of Jim Morrison". Dazed Digital. July 22, 2012. Retrieved March 17, 2021.

- Joplin, Janis (July 18, 1969). "The Dick Cavett Show" (Interview). Interviewed by Dick Cavett. New York: ABC.

- Hopkins, Jerry; Sugerman, Danny (1980). No One Here Gets Out Alive. Plexus. ISBN 978-0-85965-038-0.

- Riordan, James; Prochnicky, Jerry (1992). Break on Through: The Life and Death of Jim Morrison. New York: HarperCollins. pp. 382–384. ISBN 978-0-68811-915-7.

- ^ Kennealy, Patricia (1993). Strange Days: My Life With And Without Jim Morrison. New York: Dutton/Penguin. pp. 169–180. ISBN 978-0-45226-981-1.

- Kennealy, Patricia (1993). Strange Days: My Life With And Without Jim Morrison. New York City: Dutton/Penguin. pp. photos plate 7. ISBN 978-0-45226-981-1.

- Balfour, Victoria (January 1987). Rock Wives: The Hard Lives and Good Times of the Wives, Girlfriends, and Groupies of Rock and Roll. Beech Tree Books. p. 149. ISBN 978-0-68806-966-7.

- Hilburn, Robert (February 2, 1986). "'Rock Wives': Happy Endings Amid The Dirt". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 21, 2016.

- Kennealy (1993), p. 188 Note:

- Riordan, James; Prochnicky, Jerry (1992). Break on Through: The Life and Death of Jim Morrison. New York: HarperCollins. pp. 401–402. ISBN 978-0-68811-915-7.

- ^ Riordan, James; Prochnicky, Jerry (1992). Break on Through: The Life and Death of Jim Morrison. New York: HarperCollins. p. 448. ISBN 978-0-68811-915-7.

- Kennealy (1992), p. 315

- Davis, Stephen (2004). Jim Morrison: Life, Death, Legend. London, England: Ebury Press. ASIN B01FEKDSMW.

At the time 'Maggie M'Gill' was recorded, paternity suits against Jim Morrison were being defended by Max Fink's office. All were still pending when Jim died, and so were unresolved.

- Saroyan, Wayne A. (March 22, 1989). "The Twisted Tale Of How Late Rocker Jim Morrison's Poetry Found". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved July 11, 2017.

- ^ Gaar, Gillian G. (2015). The Doors: The Illustrated History. Minneapolis: Voyageur Press. pp. 12–13. ISBN 978-1-62788-705-2.

- More, Thomas (December 3, 2013). "The Verse of the Lizard King: An Analysis Of Jim Morrison's Work". Return of Kings. Retrieved December 1, 2015.

- ^ Manzarek, Ray (1998). Light My Fire. New York: Berkley Boulevard Books. pp. 78, 107. ISBN 978-0-425-17045-8.

- ^ Densmore, John (November 4, 2009). Riders on the Storm: My Life with Jim Morrison and The Doors. Random House. pp. 3, 286. ISBN 978-0-09993-300-7.

- ^ Tobler, John; Doe, Andrew (1984). The Doors. Proteus. ISBN 978-0-86276-069-4.

- "Interview with Jim Morrison's Father and Sister". Witnify.com. December 11, 2013. Retrieved May 3, 2023.

- Young, Ralph (2015). Dissent: The History of an American Idea. NYU Press. p. 418. ISBN 978-1-4798-1452-7.

- "Jim Morrison and Jack Kerouac – Jim Cherry". Empty Mirror. November 4, 2013. Archived from the original on February 1, 2017. Retrieved July 11, 2017.

- "Biography Channel documentary". Biography.com. Archived from the original on June 10, 2011. Retrieved December 29, 2011.

- "Cardinal Releasing". cardinalreleasing.com. Archived from the original on June 4, 2012.

Further reading

- Linda Ashcroft (1997), Wild Child: Life with Jim Morrison, ISBN 1-56025-249-9

- Lester Bangs, "Jim Morrison: Bozo Dionysus a Decade Later" in Main Lines, Blood Feasts, and Bad Taste: A Lester Bangs Reader, John Morthland, ed. Anchor Press (2003) ISBN 0-375-71367-0

- Dave DiMartino, Moonlight Drive (1995) ISBN 1-886894-21-3

- Steven Erkel, "The Poet Behind The Doors: Jim Morrison's Poetry and the 1960s Countercultural Movement" (2011)

- Wallace Fowlie, Rimbaud and Jim Morrison (1994) ISBN 0-8223-1442-8

- Jerry Hopkins, The Lizard King: The Essential Jim Morrison (1995) ISBN 0-684-81866-3

- Jerry Hopkins and Danny Sugerman, No One Here Gets Out Alive (1980) ISBN 0-85965-138-X

- Huddleston, Judy, Love Him Madly: An Intimate Memoir of Jim Morrison (2013) ISBN 9781613747506

- Mike Jahn, "Jim Morrison and The Doors", (1969) Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 71-84745

- Dylan Jones, Jim Morrison: Dark Star, (1990) ISBN 0-7475-0951-4

- Patricia Kennealy, Strange Days: My Life With and Without Jim Morrison (1992) ISBN 0-525-93419-7

- Gerry Kirstein, "Some Are Born to Endless Night: Jim Morrison, Visions of Apocalypse and Transcendence" (2012) ISBN 1451558066

- Frank Lisciandro, Morrison: A Feast of Friends (1991) ISBN 0-446-39276-6, Morrison – Un festin entre amis (1996) (French)

- Frank Lisciandro, Jim Morrison: An Hour For Magic (A Photojournal) (1982) ISBN 0-85965-246-7, James Douglas Morrison (2005) (French)

- Ray Manzarek, Light My Fire (1998) ISBN 0-446-60228-0. First by Jerry Hopkins and Danny Sugerman (1981)

- Peter Jan Margry, The Pilgrimage to Jim Morrison's Grave at Père Lachaise Cemetery: The Social Construction of Sacred Space. In idem (ed.), Shrines and Pilgrimage in the Modern World. New Itineraries into the Sacred. Amsterdam University Press, 2008, p. 145–173.

- Thanasis Michos, The Poetry of James Douglas Morrison (2001) ISBN 960-7748-23-9 (Greek)

- Daveth Milton, We Want The World: Jim Morrison, The Living Theatre, and the FBI, (2012) ISBN 978-0957051188

- Mark Opsasnick, The Lizard King Was Here: The Life and Times of Jim Morrison in Alexandria, Virginia (2006) ISBN 1-4257-1330-0

- James Riordan & Jerry Prochnicky, Break on through: The Life and Death of Jim Morrison (1991) ISBN 0-688-11915-8

- Adriana Rubio, Jim Morrison: Ceremony...Exploring the Shaman Possession (2005) ISBN

- Howard Sounes. 27: A History of the 27 Club Through the Lives of Brian Jones, Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Jim Morrison, Kurt Cobain, and Amy Winehouse, Boston: Da Capo Press, 2013. ISBN 0-306-82168-0.

- The Doors (remaining members Ray Manzarek, Robby Krieger, John Densmore) with Ben Fong-Torres, The Doors (2006) ISBN 1-4013-0303-X

- Mick Wall (2014), Love Becomes a Funeral Pyre: A Biography of The Doors

External links

- The Doors official website

- Jim Morrison discography at Discogs

- Template:Curlie

- Jim Morrison at IMDb

- Earliest film of Jim Morrison

- A lost painting collaboration with Jim Morrison intended for his An American Prayer album

- George Washington High School Alumni Association, Alexandria, Va., Morrison page

| Rock and Roll Hall of Fame – Class of 1993 | |

|---|---|

| Performers | |

| Early influences | |

| Non-performers (Ahmet Ertegun Award) | |

- Jim Morrison

- 1943 births

- 1971 deaths

- 20th-century American male musicians

- 20th-century American male singers

- 20th-century American male writers

- 20th-century American poets

- 20th-century American singer-songwriters

- American baritones

- American expatriates in France

- American male film actors

- American male poets

- American male singer-songwriters

- American people of English descent

- American people of Irish descent

- American people of Scottish descent

- American rock singers

- American rock songwriters

- Burials at Père Lachaise Cemetery

- Columbia Records artists

- Death conspiracy theories

- Elektra Records artists

- Florida State University alumni

- Musicians from Alexandria, Virginia

- Obscenity controversies in music

- People from Laurel Canyon, Los Angeles

- People from Melbourne, Florida

- People from Topanga, California

- People who have received posthumous pardons

- Psychedelic rock musicians

- Recipients of American gubernatorial pardons

- Singer-songwriters from California

- Singer-songwriters from Florida

- Singer-songwriters from Virginia

- The Doors members

- UCLA Film School alumni