This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Partofthemachine (talk | contribs) at 21:04, 6 September 2024 (→United States). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 21:04, 6 September 2024 by Partofthemachine (talk | contribs) (→United States)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) Political situation in which every citizen is subject to the law "Rule of Law" redirects here. For other uses, see Rule of Law (disambiguation). Not to be confused with Rule according to higher law.

| Part of the Politics series |

| Politics |

|---|

| Primary topics |

| Political systems |

| Academic disciplines |

Public administration

|

| Policy |

| Government branches |

| Related topics |

| Subseries |

|

|

The rule of law is a political ideal that all citizens and institutions within a country, state, or community are accountable to the same laws, including lawmakers and leaders. It is sometimes stated simply as "no one is above the law". The term rule of law is closely related to constitutionalism as well as Rechtsstaat. It refers to a political situation, not to any specific legal rule. The rule of law is defined in the Encyclopædia Britannica as "the mechanism, process, institution, practice, or norm that supports the equality of all citizens before the law, secures a nonarbitrary form of government, and more generally prevents the arbitrary use of power."

Use of the phrase can be traced to 16th-century Britain. In the following century, Scottish theologian Samuel Rutherford employed it in arguing against the divine right of kings. John Locke wrote that freedom in society means being subject only to laws written by a legislature that apply to everyone, with a person being otherwise free from both governmental and private restrictions on his liberty. "The rule of law" was further popularized in the 19th century by British jurist A. V. Dicey. However, the principle, if not the phrase itself, was recognized by ancient thinkers. Aristotle wrote: "It is more proper that law should govern than any one of the citizens: upon the same principle, if it is advantageous to place the supreme power in some particular persons, they should be appointed to be only guardians, and the servants of the laws."

The rule of law implies that every person is subject to the law, including persons who are lawmakers, law enforcement officials, and judges. Distinct is the rule of man, where one person or group of persons rule arbitrarily.

History

Early history (to 15th century)

The earliest conception of rule of law can be traced back to the Indian epics Ramayana and Mahabharata - the earliest versions of which date around to 8th or 9th centuries BC although they were written down as texts much later owing to the shruti - smriti tradition. The Mahabharata deals with the concepts of Dharma (used to mean law and duty interchangeably), Rajdharma (duty of the king) and Dharmaraja (as Yudhishthir, the eldest of the five Pandava brothers was known) and states in one of its slokas that, "A King who after having sworn that he shall protect his subjects fails to protect them should be executed like a mad dog." and also that, "The people should execute a king who does not protect them, but deprives them of their property and assets and who takes no advice or guidance from any one. Such a king is not a king but misfortune."

Other sources for the philosophy of rule of law can be traced to the Upanishads which state that, "The law is the king of the kings. No one is higher than the law. Not even the king." Other commentaries include Kautilya's Arthashastra (4th-century BC), Manusmriti (dated to the 1st to 3rd century CE), Yajnavalkya-Smriti (dated between the 3rd and 5th century CE), Brihaspati Smriti (dated between 15 CE and 16 CE).

Several scholars have also traced the concept of the rule of law back to 4th-century BC Athens, seeing it either as the dominant value of the Athenian democracy, or as one held in conjunction with the concept of popular sovereignty. However, these arguments have been challenged and the present consensus is that upholding an abstract concept of the rule of law was not "the predominant consideration" of the Athenian legal system.

Alfred the Great, Anglo-Saxon king in the 9th century, reformed the law of his kingdom and assembled a law code (the Doom Book) which he grounded on biblical commandments. He held that the same law had to be applied to all persons, whether rich or poor, friends or enemies. This was likely inspired by Leviticus 19:15: "You shall do no iniquity in judgment. You shall not favor the wretched and you shall not defer to the rich. In righteousness you are to judge your fellow."

In 1215, Archbishop Stephen Langton gathered the Barons in England and forced King John and future sovereigns and magistrates back under the rule of law, preserving ancient liberties by Magna Carta in return for exacting taxes. The influence of Magna Carta ebbs and wanes across centuries. The weakening of royal power it demonstrated was based more upon the instability presented by contested claims than thoughtful adherence to constitutional principles. Until 1534, the Church excommunicated people for violations, but after a time Magna Carta was simply replaced by other statutes considered binding upon the king to act according to "process of the law". Magna Carta's influence is considered greatly diminished by the reign of Henry VI, after the Wars of the Roses. The ideas contained in Magna Carta are widely considered to have influenced the United States Constitution.

In 1481, during the reign of Ferdinand II of Aragon, the Constitució de l'Observança was approved by the General Court of Catalonia, establishing the submission of royal power (included its officers) to the laws of the Principality of Catalonia.

The first known use of this English phrase occurred around 1500. Another early example of the phrase "rule of law" is found in a petition to James I of England in 1610, from the House of Commons:

Amongst many other points of happiness and freedom which your majesty's subjects of this kingdom have enjoyed under your royal progenitors, kings and queens of this realm, there is none which they have accounted more dear and precious than this, to be guided and governed by the certain rule of the law which giveth both to the head and members that which of right belongeth to them, and not by any uncertain or arbitrary form of government ...

Modern period (1500 CE – present)

See also: RechtsstaatIn 1607, English Chief Justice Sir Edward Coke said in the Case of Prohibitions (according to his own report) "that the law was the golden met-wand and measure to try the causes of the subjects; and which protected His Majesty in safety and peace: with which the King was greatly offended, and said, that then he should be under the law, which was treason to affirm, as he said; to which I said, that Bracton saith, quod Rex non debet esse sub homine, sed sub Deo et lege (That the King ought not to be under any man but under God and the law.)."

Among the first modern authors to use the term and give the principle theoretical foundations was Samuel Rutherford in Lex, Rex (1644). The title, Latin for "the law is king", subverts the traditional formulation rex lex ("the king is law"). James Harrington wrote in Oceana (1656), drawing principally on Aristotle's Politics, that among forms of government an "Empire of Laws, and not of Men" was preferable to an "Empire of Men, and not of Laws".

John Locke also discussed this issue in his Second Treatise of Government (1690):

The natural liberty of man is to be free from any superior power on earth, and not to be under the will or legislative authority of man, but to have only the law of nature for his rule. The liberty of man, in society, is to be under no other legislative power, but that established, by consent, in the commonwealth; nor under the dominion of any will, or restraint of any law, but what that legislative shall enact, according to the trust put in it. Freedom then is not what Sir Robert Filmer tells us, Observations, A. 55. a liberty for every one to do what he lists, to live as he pleases, and not to be tied by any laws: but freedom of men under government is, to have a standing rule to live by, common to every one of that society, and made by the legislative power erected in it; a liberty to follow my own will in all things, where the rule prescribes not; and not to be subject to the inconstant, uncertain, unknown, arbitrary will of another man: as freedom of nature is, to be under no other restraint but the law of nature.

The principle was also discussed by Montesquieu in The Spirit of Law (1748). The phrase "rule of law" appears in Samuel Johnson's Dictionary (1755).

In 1776, the notion that no one is above the law was popular during the founding of the United States. For example, Thomas Paine wrote in his pamphlet Common Sense that "in America, the law is king. For as in absolute governments the King is law, so in free countries the law ought to be king; and there ought to be no other." In 1780, John Adams enshrined this principle in Article VI of the Declaration of Rights in the Constitution of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts:

No man, nor corporation, or association of men, have any other title to obtain advantages, or particular and exclusive privileges, distinct from those of the community, than what arises from the consideration of services rendered to the public; and this title being in nature neither hereditary, nor transmissible to children, or descendants, or relations by blood, the idea of a man born a magistrate, lawgiver, or judge, is absurd and unnatural.

The influence of Britain, France and the United States contributed to spreading the principle of the rule of law to other countries around the world.

Philosophical influences

Although credit for popularizing the expression "the rule of law" in modern times is usually given to A. V. Dicey, development of the legal concept can be traced through history to many ancient civilizations, including ancient Greece, Mesopotamia, India, and Rome.

The idea of Rule of Law is often regarded as a modern iteration of the ideas of ancient Greek philosophers who argued that the best form of government was rule by the best men. Plato advocated a benevolent monarchy ruled by an idealized philosopher king, who was above the law. Plato nevertheless hoped that the best men would be good at respecting established laws, explaining that "Where the law is subject to some other authority and has none of its own, the collapse of the state, in my view, is not far off; but if law is the master of the government and the government is its slave, then the situation is full of promise and men enjoy all the blessings that the gods shower on a state." More than Plato attempted to do, Aristotle flatly opposed letting the highest officials wield power beyond guarding and serving the laws. In other words, Aristotle advocated the rule of law:

It is more proper that law should govern than any one of the citizens: upon the same principle, if it is advantageous to place the supreme power in some particular persons, they should be appointed to be only guardians, and the servants of the laws.

The Roman statesman Cicero is often cited as saying, roughly: "We are all servants of the laws in order to be free." During the Roman Republic, controversial magistrates might be put on trial when their terms of office expired. Under the Roman Empire, the sovereign was personally immune (legibus solutus), but those with grievances could sue the treasury.

In China, members of the school of legalism during the 3rd century BC argued for using law as a tool of governance, but they promoted "rule by law" as opposed to "rule of law," meaning that they placed the aristocrats and emperor above the law. In contrast, the Huang–Lao school of Daoism rejected legal positivism in favor of a natural law that even the ruler would be subject to.

Meaning and categorization of interpretations

The Oxford English Dictionary has defined rule of law this way:

The authority and influence of law in society, esp. when viewed as a constraint on individual and institutional behaviour; (hence) the principle whereby all members of a society (including those in government) are considered equally subject to publicly disclosed legal codes and processes.

Rule of law implies that every citizen is subject to the law. It stands in contrast to the idea that the ruler is above the law, for example by divine right.

Despite wide use by politicians, judges and academics, the rule of law has been described as "an exceedingly elusive notion". Among modern legal theorists, one finds that at least two principal conceptions of the rule of law can be identified: a formalist or "thin" definition, and a substantive or "thick" definition; one occasionally encounters a third "functional" conception. Formalist definitions of the rule of law do not make a judgment about the "justness" of law itself, but define specific procedural attributes that a legal framework must have in order to be in compliance with the rule of law. Substantive conceptions of the rule of law go beyond this and include certain substantive rights that are said to be based on, or derived from, the rule of law.

Most legal theorists believe that the rule of law has purely formal characteristics. For instance, such theorists claim that law requires generality (general rules that apply to classes of persons and behaviors as opposed to individuals), publicity (no secret laws), prospective application (little or no retroactive laws), consistency (no contradictory laws), equality (applied equally throughout all society), and certainty (certainty of application for a given situation), but formalists contend that there are no requirements with regard to the content of the law. Others, including a few legal theorists, believe that the rule of law necessarily entails protection of individual rights. Within legal theory, these two approaches to the rule of law are seen as the two basic alternatives, respectively labelled the formal and substantive approaches. Still, there are other views as well. Some believe that democracy is part of the rule of law.

The "formal" interpretation is more widespread than the "substantive" interpretation. Formalists hold that the law must be prospective, well-known, and have characteristics of generality, equality, and certainty. Other than that, the formal view contains no requirements as to the content of the law. This formal approach allows laws that protect democracy and individual rights, but recognizes the existence of "rule of law" in countries that do not necessarily have such laws protecting democracy or individual rights. The best known arguments for the formal interpretation have been made by A.V Dicey, F.A.Hayek, Joseph Raz, and Joseph Unger.

The substantive interpretation preferred by Dworkin, Laws, and Allan, holds that the rule of law intrinsically protects some or all individual rights.

The functional interpretation of the term rule of law, consistent with the traditional English meaning, contrasts the rule of law with the rule of man. According to the functional view, a society in which government officers have a great deal of discretion has a low degree of "rule of law", whereas a society in which government officers have little discretion has a high degree of "rule of law". Upholding the rule of law can sometimes require the punishment of those who commit offenses that are justifiable under natural law but not statutory law. The rule of law is thus somewhat at odds with flexibility, even when flexibility may be preferable.

The ancient concept of rule of law can be distinguished from rule by law, according to political science professor Li Shuguang: "The difference ... is that, under the rule of law, the law is preeminent and can serve as a check against the abuse of power. Under rule by law, the law is a mere tool for a government, that suppresses in a legalistic fashion."

Status in various jurisdictions

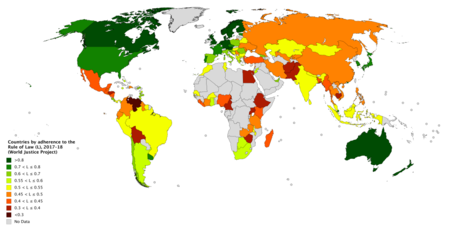

The rule of law has been considered one of the key dimensions that determine the quality and good governance of a country. Research, like the Worldwide Governance Indicators, defines the rule of law as "the extent to which agents have confidence and abide by the rules of society, and in particular the quality of contract enforcement, the police and the courts, as well as the likelihood of crime or violence." Based on this definition the Worldwide Governance Indicators project has developed aggregate measurements for the rule of law in more than 200 countries, as seen in the map at right. Other evaluations such as the World Justice Project Rule of Law Index show that adherence to rule of law fell in 61% of countries in 2022. Globally, this means that 4.4 billion people live in countries where rule of law declined in 2021.

Europe

The preamble of the rule of law European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms says "the governments of European countries which are like-minded and have a common heritage of political traditions, ideals, freedom and the rule of law".

In France and Germany the concepts of rule of law (Etat de droit and Rechtsstaat respectively) are analogous to the principles of constitutional supremacy and protection of fundamental rights from public authorities (see public law), particularly the legislature. France was one of the early pioneers of the ideas of the rule of law. The German interpretation is more "rigid" but similar to that of France and the United Kingdom.

Finland's constitution explicitly requires rule of law by stipulating that "the exercise of public powers shall be based on an Act. In all public activity, the law shall be strictly observed."

United Kingdom

Main article: Rule of law in the United Kingdom See also: History of the constitution of the United KingdomIn the United Kingdom the rule of law is a long-standing principle of the way the country is governed, dating from England's Magna Carta in 1215 and the Bill of Rights 1689. In the 19th century classic work Introduction to the Study of the Law of the Constitution (1885), A. V. Dicey, a constitutional scholar and lawyer, wrote of the twin pillars of the British constitution: the rule of law and parliamentary sovereignty.

Americas

United States

All government officers of the United States, including the President, the Justices of the Supreme Court, state judges and legislators, and all members of Congress, pledge first and foremost to uphold the Constitution. These oaths affirm that the rule of law is superior to the rule of any human leader. At the same time, the federal government has considerable discretion: the legislative branch is free to decide what statutes it will write, as long as it stays within its enumerated powers and respects the constitutionally protected rights of individuals. Likewise, the judicial branch has a degree of judicial discretion, and the executive branch also has various discretionary powers including prosecutorial discretion.

The July 1, 2024, Trump v. United States Supreme Court decision held former presidents have partial immunity for crimes committed using the powers of their office. Legal scholars have warned of the negative impact of this decision on the status of rule of law in the United States. Prior to that, in 1973 and 2000 the Office of Legal Counsel within the Department of Justice issued opinions saying that a sitting president cannot be indicted or prosecuted, but it is constitutional to indict and try a former president for the same offenses for which the President was impeached by the House of Representatives and acquitted by the Senate under the Impeachment Disqualification Clause of Article I, Section III. The question of whether a president may only be criminally charged if they have first survived an impeachment is presently before the District of Columbia Circuit Court of Appeals for decision in the case of United States of America versus Donald J. Trump (docket no. 23–3228).

Scholars continue to debate whether the U.S. Constitution adopted a particular interpretation of the "rule of law", and if so, which one. For example, John Harrison asserts that the word "law" in the Constitution is simply defined as that which is legally binding, rather than being "defined by formal or substantive criteria", and therefore judges do not have discretion to decide that laws fail to satisfy such unwritten and vague criteria. Law Professor Frederick Mark Gedicks disagrees, writing that Cicero, Augustine, Thomas Aquinas, and the framers of the U.S. Constitution believed that an unjust law was not really a law at all.

Some modern scholars contend that the rule of law has been corroded during the past century by the instrumental view of law promoted by legal realists such as Oliver Wendell Holmes and Roscoe Pound. For example, Brian Tamanaha asserts: "The rule of law is a centuries-old ideal, but the notion that law is a means to an end became entrenched only in the course of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries."

Others argue that the rule of law has survived but was transformed to allow for the exercise of discretion by administrators. For much of American history, the dominant notion of the rule of law, in this setting, has been some version of A. V. Dicey's: "no man is punishable or can be lawfully made to suffer in body or goods except for a distinct breach of law established in the ordinary legal manner before the ordinary Courts of the land." That is, individuals should be able to challenge an administrative order by bringing suit in a court of general jurisdiction. As the dockets of worker compensation commissions, public utility commissions and other agencies burgeoned, it soon became apparent that letting judges decide for themselves all the facts in a dispute (such as the extent of an injury in a worker's compensation case) would overwhelm the courts and destroy the advantages of specialization that led to the creation of administrative agencies in the first place. Even Charles Evans Hughes, a Chief Justice of the United States, believed "you must have administration, and you must have administration by administrative officers." By 1941, a compromise had emerged. If administrators adopted procedures that more or less tracked "the ordinary legal manner" of the courts, further review of the facts by "the ordinary Courts of the land" was unnecessary. That is, if you had your "day in commission", the rule of law did not require a further "day in court". Thus Dicey's rule of law was recast into a purely procedural form.

James Wilson said during the Philadelphia Convention in 1787 that, "Laws may be unjust, may be unwise, may be dangerous, may be destructive; and yet not be so unconstitutional as to justify the Judges in refusing to give them effect." George Mason agreed that judges "could declare an unconstitutional law void. But with regard to every law, however unjust, oppressive or pernicious, which did not come plainly under this description, they would be under the necessity as judges to give it a free course." Chief Justice John Marshall (joined by Justice Joseph Story) took a similar position in 1827: "When its existence as law is denied, that existence cannot be proved by showing what are the qualities of a law."

United States and definition and goal of rule of law

Various and countless way to define rule of law are known in the United States and might depend on one organization's goal including in territories with security risk:

First the Rule of Law should protect against anarchy and the Hobbesian war of all against all. Second, the Rule of Law should allow people to plan their affairs with reasonable confidence that they can know in advance the legal consequences of various actions. Third, the Rule of Law should guarantee against at least some types of official arbitrariness.

— Richard H. Fallon Jr., The Rule of Law as a Concept in International Discourse, 97 COLUM . L. REV . 1, 7-8 (1997)

the purpose of law is served by five "elements" of the rule of law:

(1) The first element is the capacity of legal rules, standards, or principles to guide people in the conduct of their affairs. People must be able to understand the law and comply with it.

(2) The second element of the Rule of Law is efficacy. The law should actually guide people, at least for the most part. In Joseph Raz's phrase, "people should be ruled by the law and obey it."

(3) The third element is stability. The law should be reasonably stable, in order to facilitate planning and coordinated action over time.

(4) The fourth element of the Rule of Law is the supremacy of legal authority. The law should rule officials, including judges, as well as ordinary citizens.

(5) The final element involves instrumentalities of impartial justice. Courts should be available to enforce the law and should employ fair procedures.

— Fallon

concept in terms of five (different) "goals" of the rule of law:

- making the state abide by the law

- ensuring equality before the law

- supplying law and order

- providing efficient and impartial justice, and

- upholding human rights— Rachel Kleinfeld

US Army doctrine and US Government inter-agency agreement

US Army doctrine and U.S. Government (USG) inter-agency agreement might see rule of law as a principle of governance

Rule of law is a principle of governance in which all persons, institutions and entities, public and private, including the state itself, are accountable to laws that are publicly promulgated, equally enforced, and independently adjudicated, and which are consistent with international human rights principles.

That principle can be broken down into seven effects:

- The state monopolizes the use of force in the resolution of disputes

- Individuals are secure in their persons and property

- The state is itself bound by law and does not act arbitrarily

- The law can be readily determined and is stable enough to allow individuals to plan their affairs

- Individuals have meaningful access to an effective and impartial legal system

- The state protects basic human rights and fundamental freedoms.

- Individuals rely on the existence of justice institutions and the content of law in the conduct of their daily lives

The complete realization of these effects represents an ideal.

Canada

In Canada, the Rule of Law is associated with A.V. Dicey: (1) that government must follow the law that it makes; (2) that no one is exempt from the operation of the law – that it applies equally to all; and (3) that general rights emerge from particular cases decided by the courts. It is mentioned in the preamble to the Constitution Act, 1982. The Constitution of Canada is "similar in principle" to the British constitution, and includes unwritten constitutional principles of democracy, judicial independence, federalism, constitutionalism and the rule of law, and the protection of minorities.

In 1959, Roncarelli v Duplessis, the Supreme Court of Canada called the Rule of Law a "fundamental postulate" of the Canadian Constitution. According to Reference Re Secession of Quebec, it encompasses, "a sense of orderliness, of subjection to known legal rules and of executive accountability to legal authority." In Canadian law, it means that the relationship between the state and the individual must be regulated by law and that the Constitution binds all governments, both federal and provincial, including the executive. With the adoption of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, the Canadian system of government was transformed to a significant extent from a system of Parliamentary supremacy to one of constitutional supremacy. The principle of the rule of law and constitutionalism is aided by acknowledging that the constitution is entrenched beyond simple majority rule. However, the notwithstanding clause operates to provide a limited "legislative override" of certain fundamental freedoms contained in the Charter, and has been invoked at different times by provincial legislatures.

In Canadian administrative law, "all exercises of public authority must find their source in law. All decision-making powers have legal limits, derived from the enabling statute itself, the common or civil law or the Constitution. Judicial review is the means by which the courts supervise those who exercise statutory powers, to ensure that they do not overstep their legal authority. The function of judicial review is therefore to ensure the legality, the reasonableness and the fairness of the administrative process and its outcomes." Administrative decision makers must adopt a culture of justification and demonstrate that their exercise of delegated public power can be “justified to citizens in terms of rationality and fairness.”

Asia

East Asian cultures are influenced by two schools of thought, Confucianism, which advocated good governance as rule by leaders who are benevolent and virtuous, and Legalism, which advocated strict adherence to law. The influence of one school of thought over the other has varied throughout the centuries. One study indicates that throughout East Asia, only South Korea, Singapore, Japan, Taiwan and Hong Kong have societies that are robustly committed to a law-bound state. According to Awzar Thi, a member of the Asian Human Rights Commission, the rule of law in Cambodia, and most of Asia is weak or nonexistent:

Apart from a number of states and territories, across the continent there is a huge gulf between the rule of law rhetoric and reality. In Thailand, the police force is favor over the rich and corrupted. In Cambodia, judges are proxies for the ruling political party ... That a judge may harbor political prejudice or apply the law unevenly are the smallest worries for an ordinary criminal defendant in Asia. More likely ones are: Will the police fabricate the evidence? Will the prosecutor bother to show up? Will the judge fall asleep? Will I be poisoned in prison? Will my case be completed within a decade?

In countries such as China and Vietnam, the transition to a market economy has been a major factor in a move toward the rule of law, because the rule of law is important to foreign investors and to economic development. It remains unclear whether the rule of law in countries like China and Vietnam will be limited to commercial matters or will spill into other areas as well, and if so whether that spillover will enhance prospects for related values such as democracy and human rights.

China

See also: Chinese law § Rule of lawIn China, the phrase fǎzhì (法治), which can be translated as "rule of law," means using the law as an instrument to facilitate social control.

Late Qing dynasty legal reforms unsuccessfully sought to implement Western legal principles including the rule of law and judicial independence. Judicial independence further decreased in the Republic of China under Chiang Kai-shek per the Kuomintang's policy of particization (danghua) under which administrative judges were required to have "deep comprehension" of the KMT's principles.

After China's Reform and Opening Up, the Communist Party emphasized the rule of law as a basic strategy and method for state management of society. Jiang Zemin first called for establishing a socialist rule of law at the Fifteenth Party Congress in 1997. Despite the CCP's Document 9 arguing that Western values have corrupted many people's understanding of the rule of law, the CCP has simultaneously endorsed governing the country in accordance with the rule of law. These factors likely suggest that the CCP is creating a rule of law with Chinese characteristics, which may simply entail modifying the Western notion of rule of law to best match China's unique political, social, and historical conditions. As Document 9 suggests, the CCP does not see judicial independence, separation of power, or constitutional forms of governance as defined by Western society, to suit China's unique form of governance. This unique version of rule of law with Chinese characteristics has led to different attempts to define China's method of governing the country by rule of law domestically and internationally. In his writings on socialist rule of law in China, Xi Jinping has emphasized traditional Chinese concepts including people as the root of the state (mingben), "the ideal of no lawsuit" (tianxia wusong), "respecting rite and stressing law" (longli zhongfa), "virtue first, penalty second" (dezhu xingfu), and "promoting virtue and being prudent in punishment" (mingde shenfa). Xi states that the two fundamental aspects of the socialist rule of law are: (1) that the political and legal organs (including courts, the police, and the procuratorate) must believe in the law and uphold the law, and (2) all political and legal officials must follow the Communist Party.

Thailand

In Thailand, a kingdom that has had a constitution since the initial attempt to overthrow the absolute monarchy system in 1932, the rule of law has been more of a principle than actual practice. Ancient prejudices and political bias have been present in the three branches of government with each of their foundings, and justice has been processed formally according to the law but in fact more closely aligned with royalist principles that are still advocated in the 21st century. In November 2013, Thailand faced still further threats to the rule of law when the executive branch rejected a supreme court decision over how to select senators.

India

In India, the longest constitutional text in the history of the world has governed that country since 1950. The Constitution of India is intended to limit the opportunity for governmental discretion and the judiciary uses judicial review to uphold the Constitution, especially the Fundamental Rights. Although some people have criticized the Indian judiciary for its judicial activism, others believe such actions are needed to safeguard the rule of law based on the Constitution as well as to preserve judicial independence, an important part of the basic structure doctrine.

Japan

Japan had centuries of tradition prior to World War II, during which there were laws, but they did not provide a central organizing principle for society, and they did not constrain the powers of government (Boadi, 2001). As the 21st century began, the percentage of people who were lawyers and judges in Japan remained very low relative to western Europe and the United States, and legislation in Japan tended to be terse and general, leaving much discretion in the hands of bureaucrats.

Organizations

This section has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Various organizations are involved in promoting the rule of law.

EU Commission

Further information: Category:Rule of law missions of the European UnionThe rule of law is enshrined in Article 2 of the Treaty on European Union as one of the common values for all Member States. Under the rule of law, all public powers always act within the constraints set out by law, in accordance with the values of democracy and fundamental rights, and under the control of independent and impartial courts. The rule of law includes principles such as legality, implying a transparent, accountable, democratic and pluralistic process for enacting laws; legal certainty; prohibiting the arbitrary exercise of executive power; effective judicial protection by independent and impartial courts, effective judicial review including respect for fundamental rights; separation of powers; and equality before the law. These principles have been recognised by the European Court of Justice and the European Court of Human Rights. In addition, the Council of Europe has developed standards and issued opinions and recommendations which provide well-established guidance to promote and uphold the rule of law.

The Council of Europe

The Statute of the Council of Europe characterizes the rule of law as one of the core principles which the establishment of the organization based on. The paragraph 3 of the preamble of the Statute of the Council of Europe states: "Reaffirming their devotion to the spiritual and moral values which are the common heritage of their peoples and the true source of individual freedom, political liberty and the rule of law, principles which form the basis of all genuine democracy." The Statute lays the compliance with the rule of law principles as a condition for the European states to be a full member of the organization.

International Commission of Jurists

In 1959, an event took place in New Delhi and speaking as the International Commission of Jurists, made a declaration as to the fundamental principle of the rule of law. The event consisted of over 185 judges, lawyers, and law professors from 53 countries. This later became known as the Declaration of Delhi. During the declaration they declared what the rule of law implied. They included certain rights and freedoms, an independent judiciary and social, economic and cultural conditions conducive to human dignity. The one aspect not included in The Declaration of Delhi, was for rule of law requiring legislative power to be subject to judicial review.

United Nations

The Secretary-General of the United Nations defines the rule of law as:

a principle of governance in which all persons, institutions and entities, public and private, including the State itself, are accountable to laws that are publicly promulgated, equally enforced and independently adjudicated, and which are consistent with international human rights norms and standards. It requires, as well, measures to ensure adherence to the principles of supremacy of law, equality before the law, accountability to the law, fairness in the application of the law, separation of powers, participation in decision-making, legal certainty, avoidance of arbitrariness and procedural and legal transparency.

The General Assembly has considered rule of law an agenda item since 1992, with renewed interest since 2006 and has adopted resolutions at its last three sessions. The Security Council has held a number of thematic debates on the rule of law, and adopted resolutions emphasizing the importance of these issues in the context of women, peace and security, children in armed conflict, and the protection of civilians in armed conflict. The Peacebuilding Commission has also regularly addressed rule of law issues with respect to countries on its agenda. The Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action also requires the rule of law be included in human rights education. Additionally, the Sustainable Development Goal 16, a component of the 2030 Agenda is aimed at promoting the rule of law at national and international levels.

In Our Common Agenda, the United Nations Secretary General wrote in paragraph 23: "In support of efforts to put people at the center of justice systems, I will promote a new vision for the rule of law, building on Sustainable Development Goal 16 and the 2012 Declaration of the High-level Meeting of the General Assembly on the Rule of Law at the National and International Levels (see resolution 67/1)."

International Bar Association

The Council of the International Bar Association passed a resolution in 2009 endorsing a substantive or "thick" definition of the rule of law:

An independent, impartial judiciary; the presumption of innocence; the right to a fair and public trial without undue delay; a rational and proportionate approach to punishment; a strong and independent legal profession; strict protection of confidential communications between lawyer and client; equality of all before the law; these are all fundamental principles of the Rule of Law. Accordingly, arbitrary arrests; secret trials; indefinite detention without trial; cruel or degrading treatment or punishment; intimidation or corruption in the electoral process, are all unacceptable. The Rule of Law is the foundation of a civilised society. It establishes a transparent process accessible and equal to all. It ensures adherence to principles that both liberate and protect. The IBA calls upon all countries to respect these fundamental principles. It also calls upon its members to speak out in support of the Rule of Law within their respective communities.

World Justice Project

The World Justice Project (WJP) is an international organization that produces independent research and data, in order to build awareness, and stimulate action to advance the rule of law.

The World Justice Project defines the rule of law as a durable system of laws, institutions, norms, and country commitment that uphold four universal principles:

- Accountability: the government and its officials and agents are accountable under the law.

- Just Law: the law is clear, publicized, and stable, and is applied evenly. It ensures human rights as well as properly, contract, and procedural rights.

- Open Government: the processes enforced are accessible, fair, and efficient.

- Accessible and Impartial Justice: justice is delivered timely by competent, ethical, and independent representatives and neutrals who are accessible, have adequate resources, and reflect the makeup of the communities they serve.

Their flagship WJP Rule of Law Index, measures the extent to which 140 countries and jurisdictions adhere to the rule of law across eight dimensions: Constraints on Government Powers, Absence of Corruption, Open Government, Fundamental Rights, Order and Security, Regulatory Enforcement, Civil Justice, and Criminal Justice.

International Development Law Organization

The International Development Law Organization (IDLO) is an intergovernmental organization with a joint focus on the promotion of rule of law and development. It works to empower people and communities to claim their rights, and provides governments with the know-how to realize them. It supports emerging economies and middle-income countries to strengthen their legal capacity and rule of law framework for sustainable development and economic opportunity. It is the only intergovernmental organization with an exclusive mandate to promote the rule of law and has experience working in more than 90 countries around the world.

The International Development Law Organization has a holistic definition of the rule of law:

More than a matter of due process, the rule of law is an enabler of justice and development. The three notions are interdependent; when realized, they are mutually reinforcing. For IDLO, as much as a question of laws and procedure, the rule of law is a culture and daily practice. It is inseparable from equality, from access to justice and education, from access to health and the protection of the most vulnerable. It is crucial for the viability of communities and nations, and for the environment that sustains them.

IDLO is headquartered in Rome and has a branch office in The Hague and has Permanent Observer Status at the United Nations General Assembly in New York City.

International Network to Promote the Rule of Law

The International Network to Promote the Rule of Law (INPROL) is a network of over 3,000 law practitioners from 120 countries and 300 organizations working on rule of law issues in post-conflict and developing countries from a policy, practice and research perspective. INPROL is based at the US Institute of Peace (USIP) in partnership with the US Department of State Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement, the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) Strategic Police Matters Unit, the Center of Excellence for Police Stability Unit, and William and Marry School of Law in the United States. Its affiliate organizations include the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Folke Bernadotte Academy, International Bar Association, International Association of Chiefs of Police, International Association of Women Police, International Corrections and Prisons Association, International Association for Court Administration, International Security Sector Advisory Team at the Geneva Centre for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces, Worldwide Association of Women Forensic Experts (WAWFE), and International Institute for Law and Human Rights.

INPROL provides an online forum for the exchange of information about best practices. Members may post questions, and expect a response from their fellow rule of law practitioners worldwide on their experiences in addressing rule of law issues.

In relation to economics

One important aspect of the rule-of-law initiatives is the study and analysis of the rule of law's impact on economic development. The rule-of-law movement cannot be fully successful in transitional and developing countries without an answer to the question: does the rule of law matter to economic development or not? Constitutional economics is the study of the compatibility of economic and financial decisions within existing constitutional law frameworks, and such a framework includes government spending on the judiciary, which, in many transitional and developing countries, is completely controlled by the executive. It is useful to distinguish between the two methods of corruption of the judiciary: corruption by the executive branch, in contrast to corruption by private actors.

The standards of constitutional economics can be used during annual budget process, and if that budget planning is transparent then the rule of law may benefit. The availability of an effective court system, to be used by the civil society in situations of unfair government spending and executive impoundment of previously authorized appropriations, is a key element for the success of the rule-of-law endeavor.

The Rule of Law is especially important as an influence on the economic development in developing and transitional countries. The term "rule of law" has been used primarily in the English-speaking countries, and it is not yet fully clarified even with regard to such well-established democracies as, for instance, Sweden, Denmark, France, Germany, or Japan. A common language between lawyers of common law and civil law countries as well as between legal communities of developed and developing countries is critically important for research of links between the rule of law and real economy.

The economist F. A. Hayek analyzed how the rule of law might be beneficial to the free market. Hayek proposed that under the rule of law, individuals would be able to make wise investments and future plans with some confidence in a successful return on investment when he stated: "under the Rule of Law the government is prevented from stultifying individual efforts by ad hoc action. Within the known rules of the game the individual is free to pursue his personal ends and desires, certain that the powers of government will not be used deliberately to frustrate his efforts."

Studies have shown that weak rule of law (for example, discretionary regulatory enforcement) discourages investment. Economists have found, for example, that a rise in discretionary regulatory enforcement caused US firms to abandon international investments.

In relation to culture

The Treaty on the Protection of Artistic and Scientific Institutions and Historic Monuments or Roerich Pact is an inter-American treaty. The most important idea of the Roerich Pact is the legal recognition that the defense of cultural objects is more important than the use or destruction of that culture for military purposes, and the protection of culture always has precedence over any military necessity. The Roerich Pact signed on 15 April 1935, by the representatives of 21 American states in the Oval Office of the White House (Washington, DC). It was the first international treaty signed in the Oval Office. The Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict is the first international treaty that focuses on the protection of cultural property in armed conflict. It was signed at The Hague, Netherlands on 14 May 1954 and entered into force on 7 August 1956. As of June 2017, it has been ratified by 128 states.

The rule of law can be hampered when there is a disconnect between legal and popular consensus. An example is intellectual property. Under the auspices of the World Intellectual Property Organization, nominally strong copyright laws have been implemented throughout most of the world; but because the attitude of much of the population does not conform to these laws, a rebellion against ownership rights has manifested in rampant piracy, including an increase in peer-to-peer file sharing. Similarly, in Russia, tax evasion is common and a person who admits he does not pay taxes is not judged or criticized by his colleagues and friends, because the tax system is viewed as unreasonable. Bribery likewise has different normative implications across cultures.

In relation to education

Education has an important role in promoting the rule of law (RoL) and a culture of lawfulness. In essence, it provides an important protective function by strengthening learners' abilities to face and overcome difficult life situations. Young people can be important contributors to a culture of lawfulness, and governments can provide educational support that nurtures positive values and attitudes in future generations.

Through education, learners are expected to acquire and develop the cognitive, socio-emotional and behavioural experiences and skills they need to develop into constructive and responsible contributors to society. Education also plays a key role in transmitting and sustaining socio-cultural norms and ensuring their continued evolution. Through formal education, children and youth are socialized to adopt certain values, behaviours, attitudes and roles that form their personal and social identity and guide them in their daily choices.

As they develop, children and youth also develop the capacity to reflect critically on norms, and to shape new norms that reflect contemporary conditions. As such, education for justice promotes and upholds the principle of the RoL by:

- Encouraging learners to value, and apply, the principles of the RoL in their daily lives, and;

- Equipping learners with the appropriate knowledge, values, attitudes, and behaviours they need to contribute to its continued improvement and regeneration in society more broadly. This can be reflected, for instance, in the way learners demand greater transparency in, or accountability of, public institutions, as well as through the everyday decisions that learners take as ethically responsible and engaged citizens, family members, workers, employers, friends, and consumers etc.

Global Citizenship Education (GCE) is built on a lifelong learning perspective. It is not only for children and youth but also for adults. It can be delivered in formal, non-formal and informal settings. For this reason, GCE is part and parcel of the Sustainable Development Goal 4 on Education (SDG4, Target 4.7). A competency framework based on a vision of learning covers three domains to create a well-rounded learning experience: Cognitive, Socio-Emotional and Behavioural.

Educational policies and programmes can support the personal and societal transformations that are needed to promote and uphold the RoL by:

- Ensuring the development and acquisition of key knowledge, values, attitudes and behaviours.

- Addressing the real learning needs and dilemmas of young people.

- Supporting positive behaviours.

- Ensuring the principles of the RoL are applied by all learning institutions and in all learning environments.

See also

- Consent of the governed – Consent as source of political legitimacy

- Constitutional liberalism – Form of government

- Due process – Requirement that courts respect all legal rights owed to people

- Equality before the law – Judicial principle

- Habeas corpus – Court action challenging unlawful detention

- International Network to Promote the Rule of Law

- Judicial activism – Controversial judicial practice

- Law of the jungle – Expression for behavior without rule of law

- Legal certainty – Legal principle

- Legal doctrine – Set of rules or procedures through which judgements can be determined in a legal case

- Liberal international order – International system established after World War II

- Might makes right – View that morality is, or ought to be, determined by those in power

- Minority rights – Rights of members of minority groups

- Nuremberg principles – Guidelines for determining what constitutes a war crime

- Ochlocracy – Democracy spoiled by demagoguery and the rule of passion over reasonPages displaying short descriptions of redirect targets (mob rule)

- Philosophy of law – Theoretical study of lawPages displaying short descriptions of redirect targets

- Public interest law – Legal practices undertaken to help poor or marginalized people

- Rechtsstaat – Continental European legal doctrine

- Right of conquest – Concept in political science

- Rule of man – Type of personal rule

- Separation of powers – Division of a state's government into branches

- Social contract – Concept in political philosophy

- Sovereign immunity – Legal doctrine

By jurisdiction

- Rule of law doctrine in Singapore – Law doctrine in SingaporePages displaying short descriptions of redirect targets

- Three Supremes, policy by which law is made subordinate to interests of the Chinese Communist Party

Legal scholars

- Thomas Bingham, Baron Bingham of Cornhill – British judge (1933–2010)Pages displaying short descriptions of redirect targets

- A. V. Dicey – British jurist and constitutional theorist (1835–1922)

- Joseph Raz – Israeli philosopher (1939–2022)

Sources

![]() This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC BY-SA (license statement/permission). Text taken from Strengthening the rule of law through education: A guide for policymakers, 63, UNESCO.

This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC BY-SA (license statement/permission). Text taken from Strengthening the rule of law through education: A guide for policymakers, 63, UNESCO.

Notes and references

- Cole, John et al. (1997). The Library of Congress, W. W. Norton & Company. p. 113

- Sempill, Julian (2020). "The Rule of Law and the Rule of Men: History, Legacy, Obscurity". Hague Journal on the Rule of Law. 12 (3): 511–540. doi:10.1007/s40803-020-00149-9. S2CID 256425870.

- "Rule of Law". National Geographic Society. 15 March 2019. Retrieved 29 January 2022.

- "Why do we say No man is above the law?".

- Ten, C. l (2017), "Constitutionalism and the Rule of Law", A Companion to Contemporary Political Philosophy, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, pp. 493–502, doi:10.1002/9781405177245.ch22, ISBN 978-1405177245

- Reynolds, Noel B. (1986). "Constitutionalism and the Rule of Law". All Faculty Publications (BYU ScholarsArchive). Archived from the original on 2019-11-07. Retrieved 2020-02-21.

- "Constitutionalism, Rule of Law, PS201H-2B3". www.proconservative.net. Archived from the original on 15 March 2018. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- "rule of law | Definition, Implications, Significance, & Facts | Britannica". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 29 January 2022.

- ^ Rutherford, Samuel. Lex, rex: the law and the prince, a dispute for the just prerogative of king and people, containing the reasons and causes of the defensive wars of the kingdom of Scotland, and of their expedition for the ayd and help of their brethren of England, p. 237 (1644): "The prince remaineth, even being a prince, a social creature, a man, as well as a king; one who must buy, sell, promise, contract, dispose: ergo, he is not regula regulans, but under rule of law ..."

- ^ Aristotle, Politics 3.16

- Hobson, Charles. The Great Chief Justice: John Marshall and the Rule of Law, p. 57 (University Press of Kansas, 1996): according to John Marshall, "the framers of the Constitution contemplated that instrument as a rule for the government of courts, as well as of the legislature."

- Paul. "Resisting the Rule of Men." . Louis ULJ 62 (2017): 333. "I will say that we have "the rule of men" or "personal rule" when those who wield the power of the state are not obliged to give reasons to those over whom that power is being wielded—from the standpoint of the ruled, the rulers may simply act on their brute desires."

- Austin, Christopher R. (2019). Pradyumna: Lover, Magician, and Son of the Avatara. Oxford University Press. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-19-005411-3. Archived from the original on 7 September 2023. Retrieved 11 January 2020.

- Brockington (1998, p. 26)

- Buitenen (1973) pp. xxiv–xxv

- Cowell, Herbert (1872). History and Constitution of the Courts and Legislative Authorities in India. Michigan: University of Michigan Press. pp. 37–56. ISBN 1278155406.

- Giri, Ananta Kumar (5 November 2001). "1". Rule of Law and Indian Society: Colonial Encounters,post-colonial experiments and beyond (PDF) (PhD thesis). Madras Institute of Development Studies. Retrieved 28 June 2024.

- "The Indian Judicial System | A Historical Survey". Allahabad High Court. Retrieved 2023-02-08.

- Giri, Ananta Kumar (5 November 2001). "1". Rule of Law and Indian Society: Colonial Encounters,post-colonial experiments and beyond (PDF) (PhD thesis). Madras Institute of Development Studies. Retrieved 28 June 2024.

- Ostwald, Martin (1986). From popular sovereignty to the sovereignty of law : law, society, and politics in fifth-century Athens. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 412–496. ISBN 9780520067981.

- Ober, Josiah (1989). Mass and elite in democratic Athens : rhetoric, ideology, and the power of the people. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. pp. 144–7, 299–300. ISBN 9780691028644.

- Liddel, Peter P. (2007). Civic obligation and individual liberty in ancient Athens. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 130–131. ISBN 978-0-19-922658-0.

- Alter, Robert (2004). The Five Books of Moses: A Translation with Commentary. W.W. Norton & Company. p. 627. ISBN 978-0-393-01955-1.

- Magna Carta (1215) translation, British Library

- Magna Carta (1297) U.S. National Archives Archived 2016-10-07 at the Wayback Machine.

- Turner, Ralph (2016). Magna Carta. Routledge.

- Ferro, Víctor: El Dret Públic Català. Les Institucions a Catalunya fins al Decret de Nova Planta; Eumo Editorial; ISBN 84-7602-203-4

- Oxford English Dictionary (OED), "Rule of Law, n.", accessed 27 April 2013. According to the OED, this sentence from about 1500 was written by John Blount: "Lawes And constitutcions be ordeyned be cause the noysome Appetit of man maye be kepte vnder the Rewle of lawe by the wiche mankinde ys dewly enformed to lyue honestly." And this sentence from 1559 is attributed to William Bavand: "A Magistrate should..kepe rekenyng of all mennes behauiours, and to be carefull, least thei despisyng the rule of lawe, growe to a wilfulnes."

- Hallam, Henry. The Constitutional History of England, vol. 1, p. 441 (1827).

- ^ "The Rule of Law". The Constitution Society. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 3 October 2014.

- Harrington, James (1747). Toland, John (ed.). The Oceana and other works (3 ed.). London: Millar. p. 37 (Internet Archive: copy possessed by John Adams).

- Locke, John. Second Treatise of Civil Government, Ch. IV, sec. 22 (1690).

- Tamanaha, Brian. On the Rule of Law, p. 47 (Cambridge University Press, 2004).

- Peacock, Anthony Arthur, Freedom and the rule of law, p. 24. 2010.

- Lieberman, Jethro. A Practical Companion to the Constitution, p. 436 (University of California Press 2005).

- Constitution of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts (1780), Part the First, Art. VI.

- Winks, Robin W. (1993). World civilization: a brief history (2nd ed.). San Diego, CA: Collegiate Press. p. 406. ISBN 978-0-939693-28-3.

- Billias, George Athan (2011). American constitutionalism heard round the world, 1776–1989: a global perspective. New York: New York University Press. pp. 53–56. ISBN 978-0-8147-2517-7.

- ^ Wormuth, Francis. The Origins of Modern Constitutionalism, p. 28 (1949).

- Bingham, Thomas. The Rule of Law, p. 3 (Penguin 2010).

- Black, Anthony. A World History of Ancient Political Thought (Oxford University Press 2009). ISBN 0-19-928169-6

- ^ David Clarke, "The many meanings of the rule of law Archived 2016-04-08 at the Wayback Machine" in Kanishka Jayasuriya, ed., Law, Capitalism and Power in Asia (New York: Routledge, 1998).

- Cooper, John et al. Complete Works By Plato, p. 1402 (Hackett Publishing, 1997).

- In full: "The magistrates who administer the law, the judges who act as its spokesmen, all the rest of us who live as its servants, grant it our allegiance as a guarantee of our freedom."—Cicero (1975). Murder Trials. Penguin Classics. Translated by Michael Grant. Harmondsworth: Penguin. p. 217. Original Latin: "Legum ministri magistratus, legum interpretes iudices, legum denique idcirco omnes servi sumus ut liberi esse possimus."—"Pro Cluentio". The Latin Library. 53:146. Retrieved 5 March 2018.

- Xiangming, Zhang. On Two Ancient Chinese Administrative Ideas: Rule of Virtue and Rule by Law Archived 17 June 2017 at the Wayback Machine, The Culture Mandala: Bulletin of the Centre for East-West Cultural and Economic Studies (2002): "Although Han Fei recommended that the government should rule by law, which seems impartial, he advocated that the law be enacted by the lords solely. The lords place themselves above the law. The law is thereby a monarchical means to control the people, not the people's means to restrain the lords. The lords are by no means on an equal footing with the people. Hence we cannot mention the rule by law proposed by Han Fei in the same breath as democracy and the rule of law advocated today."

Bevir, Mark. The Encyclopedia of Political Theory, pp. 161–162.

Munro, Donald. The Concept of Man in Early China. p. 4.

Guo, Xuezhi. The Ideal Chinese Political Leader: A Historical and Cultural Perspective. p. 152. - Peerenboom, Randall (1993). Law and morality in ancient China: the silk manuscripts of Huang-Lao. SUNY Press. p. 171. ISBN 978-0-7914-1237-4.

- Oxford English Dictionary online (accessed 13 September 2018; spelling Americanized). The phrase "the rule of law" is also sometimes used in other senses. See Garner, Bryan A. (Editor in Chief). Black's Law Dictionary, 9th Edition, p. 1448. (Thomson Reuters, 2009). ISBN 978-0-314-26578-4. Black's provides five definitions of "rule of law": the lead definition is "A substantive legal principle"; the second is the "supremacy of regular as opposed to arbitrary power".

- Tamanaha, Brian Z. (2004). On the Rule of Law. Cambridge University Press. p. 3.

- ^ Tamanaha, Brian. "The Rule of Law for Everyone?", Current Legal Problems, vol. 55, via SSRN (2002).

- Craig, Paul P. (1997). "Formal and Substantive Conceptions of the Rule of Law: An Analytical Framework". Public Law: 467.

- Donelson, Raff (2019). "Legal Inconsistencies". Tulsa Law Review. 55 (1): 15–44. SSRN 3365259.

- ^ Stephenson, Matthew. "Rule of Law as a Goal of Development Policy", World Bank Research (2008).

- Heidi M. Hurd (Aug 1992). "Justifiably Punishing the Justified". Michigan Law Review. 90 (8): 2203–2324. doi:10.2307/1289573. JSTOR 1289573.

- Tamanaha, Brian (2004). On the Rule of Law. Cambridge University Press. p. 3

- ^ Kaufman, Daniel et al. "Governance Matters VI: Governance Indicators for 1996–2006, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 4280" (July 2007).

- "Governance Matters 2008" Archived 28 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine, World Bank.

- "WJP Rule of Law Index". worldjusticeproject.org. Retrieved 2023-02-08.

- "WJP Rule of Law Index Insights". worldjusticeproject.org. Retrieved 2023-02-08.

- Pech, Laurent (10 September 2006). "Rule of Law in France". Middlesex University – School of Law. SSRN 929099.

- Letourneur, M.; Drago, R. (1958). "The Rule of Law as Understood in France". The American Journal of Comparative Law. 7 (2): 147–177. doi:10.2307/837562. JSTOR 837562.

- Peerenboom, Randall (2004). "Rule of Law in France". Asian discourses of rule of law : theories and implementation of rule of law in twelve Asian countries, France and the U.S. (Digital printing. ed.). RoutledgeCurzon. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-415-32612-4.

- Rule of Law in China: A Comparative Approach. Springer. 2014. pp. 77–78. ISBN 978-3-662-44622-5.

- Zurn, Michael; Nollkaemper, Andre; Peerenboom, Randy, eds. (2012). Rule of Law Dynamics: In an Era of International and Transnational Governance. Cambridge University Press. pp. 116–117. ISBN 978-1-139-51097-4.

- "Rule of Law". The British Library. Retrieved 3 October 2014.

- See also "The rule of law and the prosecutor". Attorney General's Office. 9 September 2013. Archived from the original on 24 July 2019. Retrieved 20 November 2014.

- Hostettler, John (2011). Champions of the rule of law. Waterside Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-1-904380-68-9.

- Vile, Josh (2006). A Companion to the United States Constitution and its Amendments. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 80

- Osborn v. Bank of the United States, 22 U.S. 738 (1824): "When are said to exercise a discretion, it is a mere legal discretion, a discretion to be exercised in discerning the course prescribed by law; and, when that is discerned, it is the duty of the court to follow it."

- For example, Lempinen, Edward High court ruling on presidential immunity threatens the rule of law, scholars warn. Berkely News

- "Can a sitting U.S. president face criminal charges?". Reuters. 26 February 2019. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- A Sitting President's Amenability to Indictment and Criminal Prosecution (PDF) (Report). Vol. 24, Opinions. Office of Legal Counsel. October 16, 2000. pp. 222–260. Retrieved January 4, 2024.

- Whether a Former President May Be Indicted and Tried for the Same Offenses for Which He Was Impeached by the House and Acquitted by the Senate (PDF) (Report). Vol. 24, Opinions. Office of Legal Counsel. August 18, 2000. pp. 110–155. Retrieved January 3, 2024.

- Rossiter, Clinton, ed. (2003) . The Federalist Papers. Signet Classics. p. 544. ISBN 978-0-451-52881-0.

- Cole, Jared P.; Garvey, Todd (December 6, 2023). Impeachment and the Constitution (Report). Congressional Research Service. pp. 14–15. Retrieved December 29, 2023.

- Harrison, John. "Substantive Due Process and the Constitutional Text," Virginia Law Review, vol. 83, p. 493 (1997).

- Gedicks, Frederick. "An Originalist Defense of Substantive Due Process: Magna Carta, Higher-Law Constitutionalism, and the Fifth Amendment", Emory Law Journal, vol. 58, pp. 585–673 (2009). See also Edlin, Douglas, "Judicial Review without a Constitution", Polity, vol. 38, pp. 345–368 (2006).

- Tamanaha, Brian. How an Instrumental View of Law Corrodes the Rule of Law, twelfth annual Clifford Symposium on Tort Law and Social Policy.

- Ernst, Daniel R. (2014). Tocqueville's Nightmare: The Administrative State Emerges in America, 1900–1940. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-992086-0

- Snowiss, Sylvia. Judicial Review and the Law of the Constitution, pp. 41–42 (Yale University Press 1990).

- Ogden v. Saunders, 25 U.S. 213, 347 (1827). This was Marshall's only dissent in a constitutional case. The individualist anarchist Lysander Spooner later denounced Marshall for this part of his Ogden dissent. See Spooner, Lysander (2008). Let's Abolish Government. Ludwig Von Mises Institute. p. 87. These same issues were also discussed in an earlier U.S. Supreme Court case, Calder v. Bull, 3 U.S. 386 (1798), with Justices James Iredell and Samuel Chase taking opposite positions. See Presser, Stephen. "Symposium: Samuel Chase: In Defense of the Rule of Law and Against the Jeffersonians", Vanderbilt Law Review, vol. 62, p. 349 (March 2009).

- ^ Rule of law, handbook, A Practitioner's Guide for Judge Advocates, 2010, The Judge Advocate General's Legal Center and School, U.S. Army Center for Law and Military Operations, Charlottesville, Virginia 22903

- Albert Venn Dicey, Introduction to the Study of the Law of the Constitution, 5th ed (London: Macmillan and Co, 1897) at 175-84, cited in "Rule of Law", Centre for Constitutional Studies, July 4, 2019

- Reference re Secession of Quebec, 1998 CanLII 793 (SCC), 2 S.C.R. 217, at paras 44-49, see also, Toronto (City) v Ontario (Attorney General), 2021 SCC 34 at para 49

- Reference Re Secession of Quebec, 2 SCR 217, at paras 70-78

- Dunsmuir v New Brunswick, 2008 SCC 9 (CanLII), 1 SCR 190, at para 28

- Canada (Minister of Citizenship and Immigration) v Vavilov, 2019 SCC 65, at para 14, citing the Rt. Hon. B. McLachlin, “The Roles of Administrative Tribunals and Courts in Maintaining the Rule of Law” (1998), 12 C.J.A.L.P. 171, at p. 174

- Chu, Yun-Han et al. How East Asians View Democracy, pp. 31–32.

- Thi, Awzar. "Asia needs a new rule-of-law debate" Archived 2013-05-07 at the Wayback Machine, United Press International, UPIAsia.com (2008-08-14).

- Peerenboom, Randall in Asian Discourses of Rule of Law, p. 39 (Routledge 2004).

- Linda Chelan Li, The “Rule of Law” Policy in Guangdong: Continuity or Departure? Meaning, Significance and Processes. (2000), 199-220.

- ^ Fang, Qiang (2024). "Understanding the Rule of Law in Xi's China". In Fang, Qiang; Li, Xiaobing (eds.). China under Xi Jinping: A New Assessment. Leiden University Press. ISBN 9789087284411. JSTOR jj.15136086.

- ^ Fang, Qiang (2024). "Understanding the Rule of Law in Xi's China". In Fang, Qiang; Li, Xiaobing (eds.). China under Xi Jinping: A New Assessment. Leiden University Press. ISBN 9789087284411.

- Wang, Zhengxu (2016). "Xi Jinping: the game changer of Chinese elite politics?". Contemporary Politics. 22 (4): 469–486. doi:10.1080/13569775.2016.1175098. S2CID 156316938. Retrieved 24 September 2023.

- Creemers, Rogier. "Communiqué on the Current State of the Ideological Sphere (Document No. 9)". DigiChina. Stanford University. Retrieved 24 September 2023.

- ^ Rudolf, Moritz (2021). "Xi Jinping Thought on the Rule of Law". SWP Comment. Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik. doi:10.18449/2021C28. S2CID 235350466. Retrieved 24 September 2023.

- Chen, Wang. "Xi Jinping Thought on the Rule of Law Is a New Development and New Leap ..." CSIS Interpret: China. CSIS. Retrieved 24 September 2023.

- Baxi, Upendra in Asian Discourses of Rule of Law, pp. 336–337 (Routledge 2004).

- Robinson, Simon. "For Activist Judges, Try India", Time Magazine (8 November 2006).

- Staff writer (2 September 2011). "Do we need judicial activism?". Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- Green, Carl. "Japan: 'The Rule of Law Without Lawyers' Reconsidered" Archived 23 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Speech to the Asia Society (14 March 2001).

- See also Goodman, Carl F. (2008). The rule of law in Japan : a comparative analysis (2nd rev. ed.). Wolters Kluwer Law & Business. ISBN 978-90-411-2750-1.

- "Communication From the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions 2020 Rule of Law Report The rule of law situation in the European Union". EUR-Lex. Retrieved 3 August 2022.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License Archived 2017-10-16 at the Wayback Machine.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License Archived 2017-10-16 at the Wayback Machine.

- "Statute of the Council of Europe". Council of Europe. Archived from the original on 2019-12-30. Retrieved 2017-12-07.

- Goldsworthy, Jeffrey. "Legislative Sovereignty and the Rule of Law" in Tom Campbell, Keith D. Ewing and Adam Tomkins (eds), Sceptical Essays on Human Rights (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), p. 69.

- What is the Rule of Law? Archived 24 September 2019 at the Wayback Machine, United Nations Rule of Law.

- See United Nations General Assembly Resolutions A/RES/61/39, A/RES/62/70, A/RES/63/128.

- See United Nations Security Council debates S/PRST/2003/15, S/PRST/2004/2, S/PRST/2004/32, S/PRST/2005/30, S/PRST/2006/28.

- See United Nations Security Council Resolutions 1325 and 1820.

- E.g. see United Nations Security Council Resolution 1612.

- E.g. see United Nations Security Council Resolution 1674.

- United Nations and the Rule of Law.

- Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action Part II, paragraph 79

- Doss, Eric. "Sustainable Development Goal 16". United Nations and the Rule of Law. Archived from the original on 20 December 2021. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- "Secretary-General's report on "Our Common Agenda"". www.un.org.

- Resolution of the Council of the International Bar Association of October 8, 2009, on the Commentary on Rule of Law Resolution (2005) Archived February 24, 2021, at the Wayback Machine.

- "World Justice Project | Advancing the rule of law worldwide". World Justice Project. Retrieved 2023-02-08.

- "WJP | Our Work". World Justice Project. Retrieved 2023-02-08.

- "WJP | What is Rule of Law?". World Justice Project. Retrieved 2023-02-08.

- "WJP | Explore the methodology, insights, dataset, and interactive data". worldjusticeproject.org. Retrieved 2023-02-08.

- "WJP | Download the full report". worldjusticeproject.org. Retrieved 2023-02-08.

- "WJP Rule of Law Index Factors". worldjusticeproject.org. Retrieved 2023-02-08.

- "IDLO – What We Do". idlo.int. 24 February 2014. Retrieved 7 February 2015.

- "IDLO Strategic Plan". Archived from the original on 8 February 2015.

- "About IDLO". IDLO – International Development Law Organization. 26 February 2014. Archived from the original on 2 October 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- "Rule of Law". IDLO – International Development Law Organization. February 24, 2014. Archived from the original on October 2, 2019. Retrieved February 15, 2022.

- "INPROL | Home". Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 9 February 2017.

- Luis Flores Ballesteros. "Corruption and development. Does the 'rule of law' factor weigh more than we think?" 54 Pesos May. 2008:54 Pesos 15 November 2008.

- Peter Barenboim, "Defining the rules", The European Lawyer, Issue 90, October 2009

- Peter Barenboim, Natalya Merkulova. "The 25th Anniversary of Constitutional Economics: The Russian Model and Legal Reform in Russia, in The World Rule of Law Movement and Russian Legal Reform" Archived 2021-02-24 at the Wayback Machine, edited by Francis Neate and Holly Nielsen, Justitsinform, Moscow (2007).

- Hayek, F.A. (1994). The Road to Serfdom. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-226-32061-8.

- Graham, Brad; Stroup, Caleb (2016). "Does Anti-bribery enforcement deter foreign investment?" (PDF). Applied Economics Letters. 23: 63–67. doi:10.1080/13504851.2015.1049333. S2CID 218640318 – via Taylor and Francis.

- Peter Barenboim, Naeem Sidiqi, Bruges, the Bridge between Civilizations: The 75 Anniversary of the Roerich Pact, Grid Belgium, 2010 Archived 2021-06-12 at the Wayback Machine. ISBN 978-5-98856-114-9

- Elisabeth Stoumatoff, FDR's Unfinished Portrait: A Memoir, University of Pittsburgh Press, 1990, ISBN 0-8229-3659-3

- "Conventions".

- Bica-Huiu, Alina, White Paper: Building a Culture of Respect for the Rule of Law, American Bar Association

- Pope, Ronald R. "The Rule of Law and Russian Culture – Are They Compatible?" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 September 2016. Retrieved 15 April 2017.

- Licht, Amir N. (December 2007). "Culture rules: The foundations of the rule of law and other norms of governance" (PDF). Journal of Comparative Economics. 35 (4): 659–688. doi:10.1016/j.jce.2007.09.001. hdl:2027.42/39991.

- ^ UNESCO and UNODC (2019). "Strengthening the rule of lawthrough education: A guide for policymakers". Archived from the original on 2020-02-25. Retrieved 2019-05-22.

- Durkheim, E (1956). Education and sociology. New York: The Free Press.

Bibliography

- Bingham, Thomas (2010). The rule of law. London New York: Allen Lane. ISBN 978-1-84614-090-7. OCLC 458734142.

- Gowder, Paul (Winter 2018). "Resisting the Rule of Men". Saint Louis University Law Journal. 62 (2).

- Oakeshott, Michael (2006). "Chapters 31 and 32". In Terry Nardin and Luke O'Sullivan (ed.). Lectures in the History of Political Thought. Exeter, UK: Imprint Academic. p. 515. ISBN 978-1-84540-093-4. OCLC 63185299.

- Shlaes, Amity, The Forgotten Man: A New History of the Great Depression, "The Rules of the Game and Economic Recovery".

- Torre, Alessandro, United Kingdom, Il Mulino, Bologna, 2005.

Further reading

- Barry, Norman (2008). "Rule of Law". In Hamowy, Ronald (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; Cato Institute. pp. 445–447. doi:10.4135/9781412965811.n273. ISBN 978-1412965804. LCCN 2008009151. OCLC 750831024.

- McDermott, John (1 January 1997). "The Rule of Law in Hong Kong after 1997". Loyola of Los Angeles International and Comparative Law Review.

External links

- Hague Journal on the Rule of Law, includes academic articles, practitioner reports, commentary, and book reviews.

- The World Justice Project A multinational, multidisciplinary initiative to strengthen the rule of law worldwide.

- "Understandings of the Rule of Law in various Legal Orders of the World", Wiki-Project of Freie Universitaet Berlin.

- Eau Claire County Bar Association rule of law talk

- Frithjof Ehm "The Rule of Law: Concept, Guiding Principle and Framework"

- Mańko, Rafał. "Using 'scoreboards' to assess justice systems" (PDF). Library Briefing. Library of the European Parliament. Retrieved 23 July 2013.