This is an old revision of this page, as edited by DVdm (talk | contribs) at 16:33, 14 October 2024 (Reverting edit(s) by 81.103.230.52 (talk) to rev. 1249886182 by Polyamorph: Vandalism (RW 16.1)). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 16:33, 14 October 2024 by DVdm (talk | contribs) (Reverting edit(s) by 81.103.230.52 (talk) to rev. 1249886182 by Polyamorph: Vandalism (RW 16.1))(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) Alternative decimal expansion of 1

In mathematics, 0.999... (also written as 0.9, 0..9, or 0.(9)) denotes the smallest number greater than every number in the sequence (0.9, 0.99, 0.999, ...). It can be proved that this number is 1; that is,

Despite common misconceptions, 0.999... is not "almost exactly 1" or "very, very nearly but not quite 1"; rather, 0.999... and "1" are exactly the same number.

An elementary proof is given below that involves only elementary arithmetic and the fact that there is no positive real number less than all 1/10, where n is a natural number, a property that results immediately from the Archimedean property of the real numbers.

There are many other ways of showing this equality, from intuitive arguments to mathematically rigorous proofs. The intuitive arguments are generally based on properties of finite decimals that are extended without proof to infinite decimals. The proofs are generally based on basic properties of real numbers and methods of calculus, such as series and limits. A question studied in mathematics education is why some people reject this equality.

In other number systems, 0.999... can have the same meaning, a different definition, or be undefined. Every nonzero terminating decimal has two equal representations (for example, 8.32000... and 8.31999...). Having values with multiple representations is a feature of all positional numeral systems that represent the real numbers.

Elementary proof

It is possible to prove the equation 0.999... = 1 using just the mathematical tools of comparison and addition of (finite) decimal numbers, without any reference to more advanced topics such as series and limits. The proof given below is a direct formalization of the intuitive fact that, if one draws 0.9, 0.99, 0.999, etc. on the number line, there is no room left for placing a number between them and 1. The meaning of the notation 0.999... is the least point on the number line lying to the right of all of the numbers 0.9, 0.99, 0.999, etc. Because there is ultimately no room between 1 and these numbers, the point 1 must be this least point, and so 0.999... = 1.

Intuitive explanation

If one places 0.9, 0.99, 0.999, etc. on the number line, one sees immediately that all these points are to the left of 1, and that they get closer and closer to 1. For any number that is less than 1, the sequence 0.9, 0.99, 0.999, and so on will eventually reach a number larger than . So, it does not make sense to identify 0.999... with any number smaller than 1. Meanwhile, every number larger than 1 will be larger than any decimal of the form 0.999...9 for any finite number of nines. Therefore, 0.999... cannot be identified with any number larger than 1, either. Because 0.999... cannot be bigger than 1 or smaller than 1, it must equal 1 if it is to be any real number at all.

Rigorous proof

Denote by 0.(9)n the number 0.999...9, with nines after the decimal point. Thus 0.(9)1 = 0.9, 0.(9)2 = 0.99, 0.(9)3 = 0.999, and so on. One has 1 − 0.(9)1 = 0.1 = , 1 − 0.(9)2 = 0.01 = , and so on; that is, 1 − 0.(9)n = for every natural number .

Let be a number not greater than 1 and greater than 0.9, 0.99, 0.999, etc.; that is, 0.(9)n < ≤ 1, for every . By subtracting these inequalities from 1, one gets 0 ≤ 1 − < .

The end of the proof requires that there is no positive number that is less than for all . This is one version of the Archimedean property, which is true for real numbers. This property implies that if 1 − < for all , then 1 − can only be equal to 0. So, = 1 and 1 is the smallest number that is greater than all 0.9, 0.99, 0.999, etc. That is, 1 = 0.999....

This proof relies on the Archimedean property of rational and real numbers. Real numbers may be enlarged into number systems, such as hyperreal numbers, with infinitely small numbers (infinitesimals) and infinitely large numbers (infinite numbers). When using such systems, the notation 0.999... is generally not used, as there is no smallest number among the numbers larger than all 0.(9)n.

Least upper bounds and completeness

Part of what this argument shows is that there is a least upper bound of the sequence 0.9, 0.99, 0.999, etc.: the smallest number that is greater than all of the terms of the sequence. One of the axioms of the real number system is the completeness axiom, which states that every bounded sequence has a least upper bound. This least upper bound is one way to define infinite decimal expansions: the real number represented by an infinite decimal is the least upper bound of its finite truncations. The argument here does not need to assume completeness to be valid, because it shows that this particular sequence of rational numbers has a least upper bound and that this least upper bound is equal to one.

Algebraic arguments

Simple algebraic illustrations of equality are a subject of pedagogical discussion and critique. Byers (2007) discusses the argument that, in elementary school, one is taught that = 0.333..., so, ignoring all essential subtleties, "multiplying" this identity by 3 gives 1 = 0.999.... He further says that this argument is unconvincing, because of an unresolved ambiguity over the meaning of the equals sign; a student might think, "It surely does not mean that the number 1 is identical to that which is meant by the notation 0.999...." Most undergraduate mathematics majors encountered by Byers feel that while 0.999... is "very close" to 1 on the strength of this argument, with some even saying that it is "infinitely close", they are not ready to say that it is equal to 1. Richman (1999) discusses how "this argument gets its force from the fact that most people have been indoctrinated to accept the first equation without thinking", but also suggests that the argument may lead skeptics to question this assumption.

Byers also presents the following argument.

Students who did not accept the first argument sometimes accept the second argument, but, in Byers's opinion, still have not resolved the ambiguity, and therefore do not understand the representation of infinite decimals. Peressini & Peressini (2007), presenting the same argument, also state that it does not explain the equality, indicating that such an explanation would likely involve concepts of infinity and completeness. Baldwin & Norton (2012), citing Katz & Katz (2010a), also conclude that the treatment of the identity based on such arguments as these, without the formal concept of a limit, is premature. Cheng (2023) concurs, arguing that knowing one can multiply 0.999... by 10 by shifting the decimal point presumes an answer to the deeper question of how one gives a meaning to the expression 0.999... at all. The same argument is also given by Richman (1999), who notes that skeptics may question whether is cancellable – that is, whether it makes sense to subtract from both sides. Eisenmann (2008) similarly argues that both the multiplication and subtraction which removes the infinite decimal require further justification.

Analytic proofs

Real analysis is the study of the logical underpinnings of calculus, including the behavior of sequences and series of real numbers. The proofs in this section establish 0.999... = 1 using techniques familiar from real analysis.

Infinite series and sequences

Further information: Decimal representationA common development of decimal expansions is to define them as sums of infinite series. In general:

For 0.999... one can apply the convergence theorem concerning geometric series, stating that if < 1, then:

Since 0.999... is such a sum with and common ratio , the theorem makes short work of the question: This proof appears as early as 1770 in Leonhard Euler's Elements of Algebra.

The sum of a geometric series is itself a result even older than Euler. A typical 18th-century derivation used a term-by-term manipulation similar to the algebraic proof given above, and as late as 1811, Bonnycastle's textbook An Introduction to Algebra uses such an argument for geometric series to justify the same maneuver on 0.999.... A 19th-century reaction against such liberal summation methods resulted in the definition that still dominates today: the sum of a series is defined to be the limit of the sequence of its partial sums. A corresponding proof of the theorem explicitly computes that sequence; it can be found in several proof-based introductions to calculus or analysis.

A sequence (, , , ...) has the value as its limit if the distance becomes arbitrarily small as increases. The statement that 0.999... = 1 can itself be interpreted and proven as a limit: The first two equalities can be interpreted as symbol shorthand definitions. The remaining equalities can be proven. The last step, that 10 approaches 0 as approaches infinity (), is often justified by the Archimedean property of the real numbers. This limit-based attitude towards 0.999... is often put in more evocative but less precise terms. For example, the 1846 textbook The University Arithmetic explains, ".999 +, continued to infinity = 1, because every annexation of a 9 brings the value closer to 1"; the 1895 Arithmetic for Schools says, "when a large number of 9s is taken, the difference between 1 and .99999... becomes inconceivably small". Such heuristics are often incorrectly interpreted by students as implying that 0.999... itself is less than 1.

Nested intervals and least upper bounds

Further information: Nested intervals

The series definition above defines the real number named by a decimal expansion. A complementary approach is tailored to the opposite process: for a given real number, define the decimal expansion(s) to name it.

If a real number is known to lie in the closed interval (that is, it is greater than or equal to 0 and less than or equal to 10), one can imagine dividing that interval into ten pieces that overlap only at their endpoints: , , , and so on up to . The number must belong to one of these; if it belongs to , then one records the digit "2" and subdivides that interval into , , ..., , . Continuing this process yields an infinite sequence of nested intervals, labeled by an infinite sequence of digits , , , ..., and one writes

In this formalism, the identities 1 = 0.999... and 1 = 1.000... reflect, respectively, the fact that 1 lies in both . and , so one can choose either subinterval when finding its digits. To ensure that this notation does not abuse the "=" sign, one needs a way to reconstruct a unique real number for each decimal. This can be done with limits, but other constructions continue with the ordering theme.

One straightforward choice is the nested intervals theorem, which guarantees that given a sequence of nested, closed intervals whose lengths become arbitrarily small, the intervals contain exactly one real number in their intersection. So , , , ... is defined to be the unique number contained within all the intervals [, + 1], [, + 0.1], and so on. 0.999... is then the unique real number that lies in all of the intervals , , , and for every finite string of 9s. Since 1 is an element of each of these intervals, 0.999... = 1.

The nested intervals theorem is usually founded upon a more fundamental characteristic of the real numbers: the existence of least upper bounds or suprema. To directly exploit these objects, one may define ... to be the least upper bound of the set of approximants , , , .... One can then show that this definition (or the nested intervals definition) is consistent with the subdivision procedure, implying 0.999... = 1 again. Tom Apostol concludes, "the fact that a real number might have two different decimal representations is merely a reflection of the fact that two different sets of real numbers can have the same supremum."

Proofs from the construction of the real numbers

Further information: Construction of the real numbersSome approaches explicitly define real numbers to be certain structures built upon the rational numbers, using axiomatic set theory. The natural numbers {0, 1, 2, 3, ...} begin with 0 and continue upwards so that every number has a successor. One can extend the natural numbers with their negatives to give all the integers, and to further extend to ratios, giving the rational numbers. These number systems are accompanied by the arithmetic of addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division. More subtly, they include ordering, so that one number can be compared to another and found to be less than, greater than, or equal to another number.

The step from rationals to reals is a major extension. There are at least two popular ways to achieve this step, both published in 1872: Dedekind cuts and Cauchy sequences. Proofs that 0.999... = 1 that directly uses these constructions are not found in textbooks on real analysis, where the modern trend for the last few decades has been to use an axiomatic analysis. Even when a construction is offered, it is usually applied toward proving the axioms of the real numbers, which then support the above proofs. However, several authors express the idea that starting with a construction is more logically appropriate, and the resulting proofs are more self-contained.

Dedekind cuts

Further information: Dedekind cutIn the Dedekind cut approach, each real number is defined as the infinite set of all rational numbers less than . In particular, the real number 1 is the set of all rational numbers that are less than 1. Every positive decimal expansion easily determines a Dedekind cut: the set of rational numbers that are less than some stage of the expansion. So the real number 0.999... is the set of rational numbers such that < 0, or < 0.9, or < 0.99, or is less than some other number of the form

Every element of 0.999... is less than 1, so it is an element of the real number 1. Conversely, all elements of 1 are rational numbers that can be written as with and . This implies and thus

Since by the definition above, every element of 1 is also an element of 0.999..., and, combined with the proof above that every element of 0.999... is also an element of 1, the sets 0.999... and 1 contain the same rational numbers, and are therefore the same set, that is, 0.999... = 1.

The definition of real numbers as Dedekind cuts was first published by Richard Dedekind in 1872. The above approach to assigning a real number to each decimal expansion is due to an expository paper titled "Is 0.999 ... = 1?" by Fred Richman in Mathematics Magazine. Richman notes that taking Dedekind cuts in any dense subset of the rational numbers yields the same results; in particular, he uses decimal fractions, for which the proof is more immediate. He also notes that typically the definitions allow { | < 1} to be a cut but not { | ≤ 1} (or vice versa). A further modification of the procedure leads to a different structure where the two are not equal. Although it is consistent, many of the common rules of decimal arithmetic no longer hold, for example, the fraction has no representation; see § Alternative number systems below.

Cauchy sequences

Further information: Cauchy sequenceAnother approach is to define a real number as the limit of a Cauchy sequence of rational numbers. This construction of the real numbers uses the ordering of rationals less directly. First, the distance between and is defined as the absolute value , where the absolute value is defined as the maximum of and , thus never negative. Then the reals are defined to be the sequences of rationals that have the Cauchy sequence property using this distance. That is, in the sequence , , , ..., a mapping from natural numbers to rationals, for any positive rational there is an such that for all ; the distance between terms becomes smaller than any positive rational.

If and are two Cauchy sequences, then they are defined to be equal as real numbers if the sequence has the limit 0. Truncations of the decimal number ... generate a sequence of rationals, which is Cauchy; this is taken to define the real value of the number. Thus in this formalism the task is to show that the sequence of rational numbers has a limit 0. Considering the th term of the sequence, for , it must therefore be shown that This can be proved by the definition of a limit. So again, 0.999... = 1.

The definition of real numbers as Cauchy sequences was first published separately by Eduard Heine and Georg Cantor, also in 1872. The above approach to decimal expansions, including the proof that 0.999... = 1, closely follows Griffiths & Hilton's 1970 work A comprehensive textbook of classical mathematics: A contemporary interpretation.

Infinite decimal representation

Commonly in secondary schools' mathematics education, the real numbers are constructed by defining a number using an integer followed by a radix point and an infinite sequence written out as a string to represent the fractional part of any given real number. In this construction, the set of any combination of an integer and digits after the decimal point (or radix point in non-base 10 systems) is the set of real numbers. This construction can be rigorously shown to satisfy all of the real axioms after defining an equivalence relation over the set that defines 1 =eq 0.999... as well as for any other nonzero decimals with only finitely many nonzero terms in the decimal string with its trailing 9s version. In other words, the equality 0.999... = 1 holding true is a necessary condition for strings of digits to behave as real numbers should.

Dense order

Further information: Dense orderOne of the notions that can resolve the issue is the requirement that real numbers be densely ordered. Dense ordering implies that if there is no new element strictly between two elements of the set, the two elements must be considered equal. Therefore, if 0.99999... were to be different from 1, there would have to be another real number in between them but there is none: a single digit cannot be changed in either of the two to obtain such a number.

Generalizations

The result that 0.999... = 1 generalizes readily in two ways. First, every nonzero number with a finite decimal notation (equivalently, endless trailing 0s) has a counterpart with trailing 9s. For example, 0.24999... equals 0.25, exactly as in the special case considered. These numbers are exactly the decimal fractions, and they are dense.

Second, a comparable theorem applies in each radix or base. For example, in base 2 (the binary numeral system) 0.111... equals 1, and in base 3 (the ternary numeral system) 0.222... equals 1. In general, any terminating base expression has a counterpart with repeated trailing digits equal to − 1. Textbooks of real analysis are likely to skip the example of 0.999... and present one or both of these generalizations from the start.

Alternative representations of 1 also occur in non-integer bases. For example, in the golden ratio base, the two standard representations are 1.000... and 0.101010..., and there are infinitely many more representations that include adjacent 1s. Generally, for almost all between 1 and 2, there are uncountably many base- expansions of 1. In contrast, there are still uncountably many , including all natural numbers greater than 1, for which there is only one base- expansion of 1, other than the trivial 1.000.... This result was first obtained by Paul Erdős, Miklos Horváth, and István Joó around 1990. In 1998 Vilmos Komornik and Paola Loreti determined the smallest such base, the Komornik–Loreti constant = 1.787231650.... In this base, 1 = 0.11010011001011010010110011010011...; the digits are given by the Thue–Morse sequence, which does not repeat.

A more far-reaching generalization addresses the most general positional numeral systems. They too have multiple representations, and in some sense, the difficulties are even worse. For example:

- In the balanced ternary system, = 0.111... = 1.111....

- In the reverse factorial number system (using bases 2!, 3!, 4!, ... for positions after the decimal point), 1 = 1.000... = 0.1234....

Petkovšek (1990) has proven that for any positional system that names all the real numbers, the set of reals with multiple representations is always dense. He calls the proof "an instructive exercise in elementary point-set topology"; it involves viewing sets of positional values as Stone spaces and noticing that their real representations are given by continuous functions.

Applications

One application of 0.999... as a representation of 1 occurs in elementary number theory. In 1802, H. Goodwyn published an observation on the appearance of 9s in the repeating-decimal representations of fractions whose denominators are certain prime numbers. Examples include:

- = 0.142857 and 142 + 857 = 999.

- = 0.01369863 and 0136 + 9863 = 9999.

E. Midy proved a general result about such fractions, now called Midy's theorem, in 1836. The publication was obscure, and it is unclear whether his proof directly involved 0.999..., but at least one modern proof by William G. Leavitt does. If it can be proved that if a decimal of the form ... is a positive integer, then it must be 0.999..., which is then the source of the 9s in the theorem. Investigations in this direction can motivate such concepts as greatest common divisors, modular arithmetic, Fermat primes, order of group elements, and quadratic reciprocity.

Returning to real analysis, the base-3 analogue 0.222... = 1 plays a key role in the characterization of one of the simplest fractals, the middle-thirds Cantor set: a point in the unit interval lies in the Cantor set if and only if it can be represented in ternary using only the digits 0 and 2.

The th digit of the representation reflects the position of the point in the th stage of the construction. For example, the point is given the usual representation of 0.2 or 0.2000..., since it lies to the right of the first deletion and the left of every deletion thereafter. The point is represented not as 0.1 but as 0.0222..., since it lies to the left of the first deletion and the right of every deletion thereafter.

Repeating nines also turns up in yet another of Georg Cantor's works. They must be taken into account to construct a valid proof, applying his 1891 diagonal argument to decimal expansions, of the uncountability of the unit interval. Such a proof needs to be able to declare certain pairs of real numbers to be different based on their decimal expansions, so one needs to avoid pairs like 0.2 and 0.1999... A simple method represents all numbers with nonterminating expansions; the opposite method rules out repeating nines. A variant that may be closer to Cantor's original argument uses base 2, and by turning base-3 expansions into base-2 expansions, one can prove the uncountability of the Cantor set as well.

Skepticism in education

Students of mathematics often reject the equality of 0.999... and 1, for reasons ranging from their disparate appearance to deep misgivings over the limit concept and disagreements over the nature of infinitesimals. There are many common contributing factors to the confusion:

- Students are often "mentally committed to the notion that a number can be represented in one and only one way by a decimal". Seeing two manifestly different decimals representing the same number appears to be a paradox, which is amplified by the appearance of the seemingly well-understood number 1.

- Some students interpret "0.999..." (or similar notation) as a large but finite string of 9s, possibly with a variable, unspecified length. If they accept an infinite string of nines, they may still expect a last 9 "at infinity".

- Intuition and ambiguous teaching lead students to think of the limit of a sequence as a kind of infinite process rather than a fixed value since a sequence need not reach its limit. Where students accept the difference between a sequence of numbers and its limit, they might read "0.999..." as meaning the sequence rather than its limit.

These ideas are mistaken in the context of the standard real numbers, although some may be valid in other number systems, either invented for their general mathematical utility or as instructive counterexamples to better understand 0.999...; see § In alternative number systems below.

Many of these explanations were found by David Tall, who has studied characteristics of teaching and cognition that lead to some of the misunderstandings he has encountered with his college students. Interviewing his students to determine why the vast majority initially rejected the equality, he found that "students continued to conceive of 0.999... as a sequence of numbers getting closer and closer to 1 and not a fixed value, because 'you haven't specified how many places there are' or 'it is the nearest possible decimal below 1'".

The elementary argument of multiplying 0.333... = by 3 can convince reluctant students that 0.999... = 1. Still, when confronted with the conflict between their belief in the first equation and their disbelief in the second, some students either begin to disbelieve the first equation or simply become frustrated. Nor are more sophisticated methods foolproof: students who are fully capable of applying rigorous definitions may still fall back on intuitive images when they are surprised by a result in advanced mathematics, including 0.999.... For example, one real analysis student was able to prove that 0.333... = using a supremum definition but then insisted that 0.999... < 1 based on her earlier understanding of long division. Others still can prove that = 0.333..., but, upon being confronted by the fractional proof, insist that "logic" supersedes the mathematical calculations.

Mazur (2005) tells the tale of an otherwise brilliant calculus student of his who "challenged almost everything I said in class but never questioned his calculator", and who had come to believe that nine digits are all one needs to do mathematics, including calculating the square root of 23. The student remained uncomfortable with a limiting argument that 9.99... = 10, calling it a "wildly imagined infinite growing process".

As part of the APOS Theory of mathematical learning, Dubinsky et al. (2005) propose that students who conceive of 0.999... as a finite, indeterminate string with an infinitely small distance from 1 have "not yet constructed a complete process conception of the infinite decimal". Other students who have a complete process conception of 0.999... may not yet be able to "encapsulate" that process into an "object conception", like the object conception they have of 1, and so they view the process 0.999... and the object 1 as incompatible. They also link this mental ability of encapsulation to viewing as a number in its own right and to dealing with the set of natural numbers as a whole.

Cultural phenomenon

With the rise of the Internet, debates about 0.999... have become commonplace on newsgroups and message boards, including many that nominally have little to do with mathematics. In the newsgroup sci.math, arguing over 0.999... is described as a "popular sport", and it is one of the questions answered in its FAQ. The FAQ briefly covers , multiplication by 10, and limits, and it alludes to Cauchy sequences as well.

A 2003 edition of the general-interest newspaper column The Straight Dope discusses 0.999... via and limits, saying of misconceptions,

The lower primate in us still resists, saying: .999~ doesn't really represent a number, then, but a process. To find a number we have to halt the process, at which point the .999~ = 1 thing falls apart. Nonsense.

A Slate article reports that the concept of 0.999... is "hotly disputed on websites ranging from World of Warcraft message boards to Ayn Rand forums". 0.999... features also in mathematical jokes, such as:

Q: How many mathematicians does it take to screw in a lightbulb?

A: 0.999999....

The fact that 0.999... is equal to 1 has been compared to Zeno's paradox of the runner. The runner paradox can be mathematically modeled and then, like 0.999..., resolved using a geometric series. However, it is not clear whether this mathematical treatment addresses the underlying metaphysical issues Zeno was exploring.

In alternative number systems

Although the real numbers form an extremely useful number system, the decision to interpret the notation "0.999..." as naming a real number is ultimately a convention, and Timothy Gowers argues in Mathematics: A Very Short Introduction that the resulting identity 0.999... = 1 is a convention as well:

However, it is by no means an arbitrary convention, because not adopting it forces one either to invent strange new objects or to abandon some of the familiar rules of arithmetic.

Infinitesimals

Main article: InfinitesimalSome proofs that 0.999... = 1 rely on the Archimedean property of the real numbers: that there are no nonzero infinitesimals. Specifically, the difference 1 − 0.999... must be smaller than any positive rational number, so it must be an infinitesimal; but since the reals do not contain nonzero infinitesimals, the difference is zero, and therefore the two values are the same.

However, there are mathematically coherent ordered algebraic structures, including various alternatives to the real numbers, which are non-Archimedean. Non-standard analysis provides a number system with a full array of infinitesimals (and their inverses). A. H. Lightstone developed a decimal expansion for hyperreal numbers in (0, 1). Lightstone shows how to associate each number with a sequence of digits, indexed by the hypernatural numbers. While he does not directly discuss 0.999..., he shows the real number is represented by 0.333...;...333..., which is a consequence of the transfer principle. As a consequence the number 0.999...;...999... = 1. With this type of decimal representation, not every expansion represents a number. In particular "0.333...;...000..." and "0.999...;...000..." do not correspond to any number.

The standard definition of the number 0.999... is the limit of the sequence 0.9, 0.99, 0.999, .... A different definition involves an ultralimit, i.e., the equivalence class of this sequence in the ultrapower construction, which is a number that falls short of 1 by an infinitesimal amount. More generally, the hyperreal number = 0.999...;...999000..., with last digit 9 at infinite hypernatural rank , satisfies a strict inequality . Accordingly, an alternative interpretation for "zero followed by infinitely many 9s" could be All such interpretations of "0.999..." are infinitely close to 1. Ian Stewart characterizes this interpretation as an "entirely reasonable" way to rigorously justify the intuition that "there's a little bit missing" from 1 in 0.999.... Along with Katz & Katz (2010b), Ely (2010) also questions the assumption that students' ideas about 0.999... < 1 are erroneous intuitions about the real numbers, interpreting them rather as nonstandard intuitions that could be valuable in the learning of calculus.

Hackenbush

Combinatorial game theory provides a generalized concept of number that encompasses the real numbers and much more besides. For example, in 1974, Elwyn Berlekamp described a correspondence between strings of red and blue segments in Hackenbush and binary expansions of real numbers, motivated by the idea of data compression. For example, the value of the Hackenbush string LRRLRLRL... is 0.010101...2 = . However, the value of LRLLL... (corresponding to 0.111...2 is infinitesimally less than 1. The difference between the two is the surreal number , where is the first infinite ordinal; the relevant game is LRRRR... or 0.000...2.

This is true of the binary expansions of many rational numbers, where the values of the numbers are equal but the corresponding binary tree paths are different. For example, 0.10111...2 = 0.11000...2, which are both equal to , but the first representation corresponds to the binary tree path LRLRLLL..., while the second corresponds to the different path LRLLRRR....

Revisiting subtraction

Another manner in which the proofs might be undermined is if 1 − 0.999... simply does not exist because subtraction is not always possible. Mathematical structures with an addition operation but not a subtraction operation include commutative semigroups, commutative monoids, and semirings. Richman (1999) considers two such systems, designed so that 0.999... < 1.

First, Richman (1999) defines a nonnegative decimal number to be a literal decimal expansion. He defines the lexicographical order and an addition operation, noting that 0.999... < 1 simply because 0 < 1 in the ones place, but for any nonterminating , one has 0.999... + = 1 + . So one peculiarity of the decimal numbers is that addition cannot always be canceled; another is that no decimal number corresponds to . After defining multiplication, the decimal numbers form a positive, totally ordered, commutative semiring.

In the process of defining multiplication, Richman also defines another system he calls "cut ", which is the set of Dedekind cuts of decimal fractions. Ordinarily, this definition leads to the real numbers, but for a decimal fraction he allows both the cut (, ) and the "principal cut" (, ]. The result is that the real numbers are "living uneasily together with" the decimal fractions. Again 0.999... < 1. There are no positive infinitesimals in cut , but there is "a sort of negative infinitesimal", 0, which has no decimal expansion. He concludes that 0.999... = 1 + 0, while the equation "0.999... + = 1" has no solution.

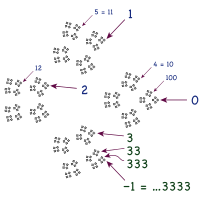

p-adic numbers

Main article: p-adic numberWhen asked about 0.999..., novices often believe there should be a "final 9", believing 1 − 0.999... to be a positive number which they write as "0.000...1". Whether or not that makes sense, the intuitive goal is clear: adding a 1 to the final 9 in 0.999... would carry all the 9s into 0s and leave a 1 in the ones place. Among other reasons, this idea fails because there is no "final 9" in 0.999.... However, there is a system that contains an infinite string of 9s including a last 9.

The -adic numbers are an alternative number system of interest in number theory. Like the real numbers, the -adic numbers can be built from the rational numbers via Cauchy sequences; the construction uses a different metric in which 0 is closer to , and much closer to , than it is to 1. The -adic numbers form a field for prime and a ring for other , including 10. So arithmetic can be performed in the -adics, and there are no infinitesimals.

In the 10-adic numbers, the analogues of decimal expansions run to the left. The 10-adic expansion ...999 does have a last 9, and it does not have a first 9. One can add 1 to the ones place, and it leaves behind only 0s after carrying through: 1 + ...999 = ...000 = 0, and so ...999 = −1. Another derivation uses a geometric series. The infinite series implied by "...999" does not converge in the real numbers, but it converges in the 10-adics, and so one can re-use the familiar formula:

Compare with the series in the section above. A third derivation was invented by a seventh-grader who was doubtful over her teacher's limiting argument that 0.999... = 1 but was inspired to take the multiply-by-10 proof above in the opposite direction: if = ...999, then 10 = ...990, so 10 = − 9, hence = −1 again.

As a final extension, since 0.999... = 1 (in the reals) and ...999 = −1 (in the 10-adics), then by "blind faith and unabashed juggling of symbols" one may add the two equations and arrive at ...999.999... = 0. This equation does not make sense either as a 10-adic expansion or an ordinary decimal expansion, but it turns out to be meaningful and true in the doubly infinite decimal expansion of the 10-adic solenoid, with eventually repeating left ends to represent the real numbers and eventually repeating right ends to represent the 10-adic numbers.

See also

Notes

- For example, one can show this as follows: if x is any number such that 0.(9)n ≤ x < 1, then 0.(9)n−1 ≤ 10x − 9 < x < 1. Thus if x has this property for all n, the smaller number 10x − 9 does, as well.

- The limit follows, for example, from Rudin (1976), p. 57, Theorem 3.20e. For a more direct approach, see also Finney, Weir & Giordano (2001), section 8.1, example 2(a), example 6(b).

- The historical synthesis is claimed by Griffiths & Hilton (1970), p. xiv and again by Pugh (2002), p. 10; both actually prefer Dedekind cuts to axioms. For the use of cuts in textbooks, see Pugh (2002), p. 17 or Rudin (1976), p. 17. For viewpoints on logic, see Pugh (2002), p. 10, Rudin (1976), p.ix, or Munkres (2000), p. 30.

- Enderton (1977), p. 113 qualifies this description: "The idea behind Dedekind cuts is that a real number x can be named by giving an infinite set of rationals, namely all the rationals less than x. We will in effect define x to be the set of rationals smaller than x. To avoid circularity in the definition, we must be able to characterize the sets of rationals obtainable in this way ..."

- Rudin (1976), pp. 17–20, Richman (1999), p. 399, or Enderton (1977), p. 119. To be precise, Rudin, Richman, and Enderton call this cut 1∗, 1−, and 1R, respectively; all three identify it with the traditional real number 1. Note that what Rudin and Enderton call a Dedekind cut, Richman calls a "non-principal Dedekind cut".

- Maor (1987), p. 60 and Mankiewicz (2000), p. 151 review the former method; Mankiewicz attributes it to Cantor, but the primary source is unclear. Munkres (2000), p. 50 mentions the latter method.

- Bunch (1982), p. 119; Tall & Schwarzenberger (1978), p. 6. The last suggestion is due to Burrell (1998), p. 28: "Perhaps the most reassuring of all numbers is 1 ... So it is particularly unsettling when someone tries to pass off 0.9~ as 1."

- For a full treatment of non-standard numbers, see Robinson (1996).

- Stewart (2009), p. 175; the full discussion of 0.999... is spread through pp. 172–175.

- Berlekamp, Conway & Guy (1982), pp. 79–80, 307–311 discuss 1 and 1/3 and touch on 1/ω. The game for 0.111...2 follows directly from Berlekamp's Rule.

- Richman (1999), pp. 398–400. Rudin (1976), p. 23 assigns this alternative construction (but over the rationals) as the last exercise of Chapter 1.

References

- Cheng (2023), p. 141.

- Diamond (1955).

- Baldwin & Norton (2012).

- Meier & Smith (2017), §8.2.

- Stewart (2009), p. 175.

- Propp (2023).

- Stillwell (1994), p. 42.

- Earl & Nicholson (2021), "bound".

- ^ Rosenlicht (1985), p. 27.

- Bauldry (2009), p. 47.

- Byers (2007), p. 39.

- ^ Richman (1999).

- Peressini & Peressini (2007), p. 186.

- Baldwin & Norton (2012); Katz & Katz (2010a).

- Cheng (2023), p. 136.

- Eisenmann (2008), p. 38.

- Tao (2003).

- Rudin (1976), p. 61, Theorem 3.26; Stewart (1999), p. 706.

- Euler (1822), p. 170.

- Grattan-Guinness (1970), p. 69; Bonnycastle (1806), p. 177.

- Stewart (1999), p. 706; Rudin (1976), p. 61; Protter & Morrey (1991), p. 213; Pugh (2002), p. 180; Conway (1978), p. 31.

- Davies (1846), p. 175; Smith & Harrington (1895), p. 115.

- ^ Tall (2000), p. 221.

- Beals (2004), p. 22; Stewart (2009), p. 34.

- Bartle & Sherbert (1982), pp. 60–62; Pedrick (1994), p. 29; Sohrab (2003), p. 46.

- Apostol (1974), pp. 9, 11–12; Beals (2004), p. 22; Rosenlicht (1985), p. 27.

- Apostol (1974), p. 12.

- Cheng (2023), pp. 153–156.

- Conway (2001), pp. 25–27.

- Rudin (1976), pp. 3, 8.

- Richman (1999), p. 399.

- ^ O'Connor & Robertson (2005).

- Richman (1999), p. 398–399. "Why do that? Precisely to rule out the existence of distinct numbers 0.9 and 1. So we see that in the traditional definition of the real numbers, the equation 0.9 = 1 is built in at the beginning."

- Griffiths & Hilton (1970), p. 386, §24.2 "Sequences".

- Griffiths & Hilton (1970), pp. 388, 393.

- Griffiths & Hilton (1970), p. 395.

- Griffiths & Hilton (1970), pp. viii, 395.

- Gowers (2001).

- Li (2011).

- Artigue (2002), p. 212, "... the ordering of the real numbers is recognized as a dense order. However, depending on the context, students can reconcile this property with the existence of numbers just before or after a given number (0.999... is thus often seen as the predecessor of 1).".

- Petkovšek (1990), p. 408.

- Protter & Morrey (1991), p. 503; Bartle & Sherbert (1982), p. 61.

- Komornik & Loreti (1998), p. 636.

- Kempner (1936), p. 611; Petkovšek (1990), p. 409.

- Petkovšek (1990), pp. 410–411.

- Goodwyn (1802); Dickson (1919), pp. 161.

- Leavitt (1984), p. 301.

- Ginsberg (2004), pp. 26–30; Lewittes (2006), pp. 1–3; Leavitt (1967), pp. 669, 673; Shrader-Frechette (1978), pp. 96–98.

- Pugh (2002), p. 97; Alligood, Sauer & Yorke (1996), pp. 150–152; Protter & Morrey (1991), p. 507; Pedrick (1994), p. 29.

- Rudin (1976), p. 50; Pugh (2002), p. 98.

- Tall & Schwarzenberger (1978), pp. 6–7; Tall (2000), p. 221.

- Tall & Schwarzenberger (1978), p. 6; Tall (2000), p. 221.

- Tall (1976), pp. 10–14.

- Pinto & Tall (2001), p. 5; Edwards & Ward (2004), pp. 416–417.

- Mazur (2005), pp. 137–141.

- Dubinsky et al. (2005), pp. 261–262.

- Richman (1999), p. 396.

- de Vreught (1994).

- Adams (2003).

- Ellenberg (2014).

- Renteln & Dundes (2005), p. 27.

- Richman (1999); Adams (2003); Ellenberg (2014).

- Wallace (2003), p. 51; Maor (1987), p. 17.

- Gowers (2002), p. 60.

- Lightstone (1972), pp. 245–247.

- Tao (2012), pp. 156–180.

- Katz & Katz (2010a).

- Katz & Katz (2010b); Ely (2010).

- Conway (2001), pp. 3–5, 12–13, 24–27.

- Richman (1999), pp. 397–399.

- Gardiner (2003), p. 98; Gowers (2002), p. 60.

- Mascari & Miola (1988), p. 83–84.

- ^ Fjelstad (1995), p. 11.

- Fjelstad (1995), pp. 14–15.

- DeSua (1960), p. 901.

- DeSua (1960), p. 902–903.

Sources

- Adams, Cecil (11 July 2003). "An infinite question: Why doesn't .999~ = 1?". The Straight Dope. Chicago Reader. Archived from the original on 15 August 2006. Retrieved 6 September 2006.

- Alligood, K. T.; Sauer, T. D.; Yorke, J. A. (1996). "4.1 Cantor Sets". Chaos: An introduction to dynamical systems. Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-94677-1.

- This introductory textbook on dynamical systems is aimed at undergraduate and beginning graduate students. (p. ix)

- Apostol, Tom M. (1974). Mathematical Analysis (2e ed.). Addison-Wesley. ISBN 978-0-201-00288-1.

- A transition from calculus to advanced analysis, Mathematical analysis is intended to be "honest, rigorous, up to date, and, at the same time, not too pedantic". (pref.) Apostol's development of the real numbers uses the least upper bound axiom and introduces infinite decimals two pages later. (pp. 9–11)

- Artigue, Michèle (2002). Holton, Derek; Artigue, Michèle; Kirchgräber, Urs; Hillel, Joel; Niss, Mogens; Schoenfeld, Alan (eds.). The Teaching and Learning of Mathematics at University Level. New ICMI Study Series. Vol. 7. Springer, Dordrecht. doi:10.1007/0-306-47231-7. ISBN 978-0-306-47231-2.

- Baldwin, Michael; Norton, Anderson (2012). "Does 0.999... Really Equal 1?". The Mathematics Educator. 21 (2): 58–67.

- Bauldry, William C. (2009). Introduction to Real Analysis: An Educational Approach. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-37136-7.

- This book is intended as introduction to real analysis aimed at upper- undergraduate and graduate-level. (pp. xi-xii)

- Bartle, R. G.; Sherbert, D. R. (1982). Introduction to Real Analysis. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-05944-8.

- This text aims to be "an accessible, reasonably paced textbook that deals with the fundamental concepts and techniques of real analysis". Its development of the real numbers relies on the supremum axiom. (pp. vii–viii)

- Beals, Richard (2004). Analysis: An Introduction. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-60047-7.

- Berlekamp, E. R.; Conway, J. H.; Guy, R. K. (1982). Winning Ways for your Mathematical Plays. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-091101-1.

- Bonnycastle, John (1806). An introduction to algebra; with notes and observations: designed for the use of schools and places of public education (First American ed.). Philadelphia. hdl:2027/mdp.39015063620382.

- Bunch, Bryan H. (1982). Mathematical Fallacies and Paradoxes. Van Nostrand Reinhold. ISBN 978-0-442-24905-2.

- This book presents an analysis of paradoxes and fallacies as a tool for exploring its central topic, "the rather tenuous relationship between mathematical reality and physical reality". It assumes first-year high-school algebra; further mathematics is developed in the book, including geometric series in Chapter 2. Although 0.999... is not one of the paradoxes to be fully treated, it is briefly mentioned during a development of Cantor's diagonal method. (pp. ix-xi, 119)

- Burrell, Brian (1998). Merriam-Webster's Guide to Everyday Math: A Home and Business Reference. Merriam-Webster. ISBN 978-0-87779-621-3.

- Byers, William (2007). How Mathematicians Think: Using Ambiguity, Contradiction, and Paradox to Create Mathematics. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-12738-5.

- Cheng, Eugenia (2023). Is Math Real? How Simple Questions Lead Us To Mathematics' Deepest Truths. Basic Books. ISBN 978-1-541-6-01826.

- Conway, John B. (1978) . Functions of One Complex Variable I (2e ed.). Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-0-387-90328-6.

- Conway, John H. (2001). On Numbers and Games (2nd ed.). A K Peters. ISBN 1-56881-127-6.

- Davies, Charles (1846). The University Arithmetic: Embracing the Science of Numbers, and Their Numerous Applications. A.S. Barnes. p. 175. Retrieved 4 July 2011.

- de Vreught, Hans (1994). "sci.math FAQ: Why is 0.9999... = 1?". Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 29 June 2006.

- DeSua, Frank C. (November 1960). "A System Isomorphic to the Reals". The American Mathematical Monthly. 67 (9): 900–903. doi:10.2307/2309468. JSTOR 2309468.

- Diamond, Louis E. (1955). "Irrational Numbers". Mathematics Magazine. 29 (2). Mathematical Association of America: 89–99. doi:10.2307/3029588. JSTOR 3029588.

- Dickson, Leonard Eugene (1919). History of the Theory of Numbers. Vol. 1. Carnegie Institution of Washington.

- Dubinsky, Ed; Weller, Kirk; McDonald, Michael; Brown, Anne (2005). "Some historical issues and paradoxes regarding the concept of infinity: an APOS analysis: part 2". Educational Studies in Mathematics. 60 (2): 253–266. doi:10.1007/s10649-005-0473-0. S2CID 45937062.

- Earl, Richard; Nicholson, James (2021). The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Mathematics (6th ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-192-58405-2.

- Edwards, Barbara; Ward, Michael (May 2004). "Surprises from mathematics education research: Student (mis)use of mathematical definitions" (PDF). The American Mathematical Monthly. 111 (5): 411–425. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.453.7466. doi:10.2307/4145268. JSTOR 4145268. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 4 July 2011.

- Ellenberg, Jordan (6 June 2014). "Does 0.999... = 1? And Are Divergent Series the Invention of the Devil?". Slate. Archived from the original on 8 August 2023.

- Ely, Robert (2010). "Nonstandard student conceptions about infinitesimals". Journal for Research in Mathematics Education. 41 (2): 117–146. doi:10.5951/jresematheduc.41.2.0117.

- This article is a field study involving a student who developed a Leibnizian-style theory of infinitesimals to help her understand calculus, and in particular to account for 0.999... falling short of 1 by an infinitesimal 0.000...1.

- Enderton, Herbert B. (1977). Elements of Set Theory. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-12-238440-0.

- An introductory undergraduate textbook in set theory that "presupposes no specific background". It is written to accommodate a course focusing on axiomatic set theory or on the construction of number systems; the axiomatic material is marked such that it may be de-emphasized. (pp. xi–xii)

- Euler, Leonhard (1822) . Elements of Algebra. John Hewlett and Francis Horner, English translators (3rd English ed.). Orme Longman. p. 170. ISBN 978-0-387-96014-2. Retrieved 4 July 2011.

- Finney, Ross L.; Weir, Maurice D.; Giordano, Frank R. (2001). Thomas' Calculus: Early Transcendentals (10th ed.). New York: Addison-Wesley.

- Fjelstad, Paul (January 1995). "The Repeating Integer Paradox". The College Mathematics Journal. 26 (1): 11–15. doi:10.2307/2687285. JSTOR 2687285.

- Gardiner, Anthony (2003) . Understanding Infinity: The Mathematics of Infinite Processes. Dover. ISBN 978-0-486-42538-2.

- Ginsberg, Brian (2004). "Midy's (nearly) secret theorem – an extension after 165 years". The College Mathematics Journal. 35 (1): 26–30. doi:10.1080/07468342.2004.11922047.

- Goodwyn, H. (1802). "Curious properties of prime Numbers, taken as the Divisors of unity. By a Correspondent". Journal of Natural Philosophy, Chemistry, and the Arts. New Series. 1: 314–316.

- Gowers, Timothy (2001). "What is so wrong with thinking of real numbers as infinite decimals?". Department of Pure Mathematics and Mathematical Statistics. Cambridge University. Retrieved 3 October 2024.

- Gowers, Timothy (2002). Mathematics: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-285361-5.

- Grattan-Guinness, Ivor (1970). The Development of the Foundations of Mathematical Analysis from Euler to Riemann. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-07034-8.

- Griffiths, H. B.; Hilton, P. J. (1970). A Comprehensive Textbook of Classical Mathematics: A Contemporary Interpretation. London: Van Nostrand Reinhold. ISBN 978-0-442-02863-3. LCC QA37.2 G75.

- This book grew out of a course for Birmingham-area grammar school mathematics teachers. The course was intended to convey a university-level perspective on school mathematics, and the book is aimed at students "who have reached roughly the level of completing one year of specialist mathematical study at a university". The real numbers are constructed in Chapter 24, "perhaps the most difficult chapter in the entire book", although the authors ascribe much of the difficulty to their use of ideal theory, which is not reproduced here. (pp. vii, xiv)

- Katz, Karin Usadi; Katz, Mikhail G. (2010a). "When is .999... less than 1?". The Montana Mathematics Enthusiast. 7 (1): 3–30. arXiv:1007.3018. Bibcode:2010arXiv1007.3018U. doi:10.54870/1551-3440.1381. S2CID 11544878. Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 4 July 2011.

- Katz, Karin Usadi; Katz, Mikhail G. (2010b). "Zooming in on infinitesimal 1 − .9.. in a post-triumvirate era". Educational Studies in Mathematics. 74 (3): 259. arXiv:1003.1501. Bibcode:2010arXiv1003.1501K. doi:10.1007/s10649-010-9239-4. S2CID 115168622.

- Kempner, Aubrey J. (December 1936). "Anormal Systems of Numeration". The American Mathematical Monthly. 43 (10): 610–617. doi:10.2307/2300532. JSTOR 2300532.

- Komornik, Vilmos; Loreti, Paola (1998). "Unique Developments in Non-Integer Bases". The American Mathematical Monthly. 105 (7): 636–639. doi:10.2307/2589246. JSTOR 2589246.

- Li, Liangpan (March 2011). "A new approach to the real numbers". arXiv:1101.1800 .

- Leavitt, William G. (1967). "A Theorem on Repeating Decimals". The American Mathematical Monthly. 74 (6): 669–673. doi:10.2307/2314251. JSTOR 2314251.

- Leavitt, William G. (September 1984). "Repeating Decimals". The College Mathematics Journal. 15 (4): 299–308. doi:10.2307/2686394. JSTOR 2686394.

- Lewittes, Joseph (2006). "Midy's Theorem for Periodic Decimals". arXiv:math.NT/0605182.

- Lightstone, Albert H. (March 1972). "Infinitesimals". The American Mathematical Monthly. 79 (3): 242–251. doi:10.2307/2316619. JSTOR 2316619.

- Mankiewicz, Richard (2000). The Story of Mathematics. Cassell. ISBN 978-0-304-35473-3.

- Mankiewicz seeks to represent "the history of mathematics in an accessible style" by combining visual and qualitative aspects of mathematics, mathematicians' writings, and historical sketches. (p. 8)

- Mascari, Gianfranco; Miola, Alfonso (1988). "On the integration of numeric and algebraic computations". In Beth, Thomas; Clausen, Michael (eds.). Applicable Algebra, Error-Correcting Codes, Combinatorics and Computer Algebra. doi:10.1007/BFb0039172. ISBN 978-3-540-39133-3.

- Maor, Eli (1987). To Infinity and Beyond: A Cultural History of the Infinite. Birkhäuser. ISBN 978-3-7643-3325-6.

- A topical rather than chronological review of infinity, this book is "intended for the general reader" but "told from the point of view of a mathematician". On the dilemma of rigor versus readable language, Maor comments, "I hope I have succeeded in properly addressing this problem." (pp. x-xiii)

- Mazur, Joseph (2005). Euclid in the Rainforest: Discovering Universal Truths in Logic and Math. Pearson: Pi Press. ISBN 978-0-13-147994-4.

- Meier, John; Smith, Derek (2017). Exploring Mathematics: An Engaging Introduction to Proof. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-12898-9.

- Munkres, James R. (2000) . Topology (2e ed.). Prentice-Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-181629-9.

- Intended as an introduction "at the senior or first-year graduate level" with no formal prerequisites: "I do not even assume the reader knows much set theory." (p. xi) Munkres's treatment of the reals is axiomatic; he claims of bare-hands constructions, "This way of approaching the subject takes a good deal of time and effort and is of greater logical than mathematical interest." (p. 30)

- Navarro, Maria Angeles; Carreras, Pedro Pérez (2010). "A Socratic methodological proposal for the study of the equality 0.999...=1" (PDF). The Teaching of Mathematics. 13 (1): 17–34. Retrieved 4 July 2011.

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F. (October 2005), "The real numbers: Stevin to Hilbert", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews

- Pedrick, George (1994). A First Course in Analysis. Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-94108-0.

- Peressini, Anthony; Peressini, Dominic (2007). "Philosophy of Mathematics and Mathematics Education". In van Kerkhove, Bart; van Bendegem, Jean Paul (eds.). Perspectives on Mathematical Practices. Logic, Epistemology, and the Unity of Science. Vol. 5. Springer. ISBN 978-1-4020-5033-6.

- Petkovšek, Marko (May 1990). "Ambiguous Numbers are Dense". American Mathematical Monthly. 97 (5): 408–411. doi:10.2307/2324393. JSTOR 2324393.

- Pinto, Márcia; Tall, David O. (2001). PME25: Following students' development in a traditional university analysis course (PDF). pp. v4: 57–64. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 May 2009. Retrieved 3 May 2009.

- Propp, James (17 September 2015). "The One About .999..." Mathematical Enchantments. Retrieved 24 May 2024.

- Propp, James (17 January 2023). "Denominators and Doppelgängers". Mathematical Enchantments. Retrieved 16 April 2024.

- Protter, Murray H.; Morrey, Charles B. Jr. (1991). A First Course in Real Analysis (2e ed.). Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-97437-8.

- This book aims to "present a theoretical foundation of analysis that is suitable for students who have completed a standard course in calculus". (p. vii) At the end of Chapter 2, the authors assume as an axiom for the real numbers that bounded, nondecreasing sequences converge, later proving the nested intervals theorem and the least upper bound property. (pp. 56–64) Decimal expansions appear in Appendix 3, "Expansions of real numbers in any base". (pp. 503–507)

- Pugh, Charles Chapman (2002). Real Mathematical Analysis. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-0-387-95297-0.

- While assuming familiarity with the rational numbers, Pugh introduces Dedekind cuts as soon as possible, saying of the axiomatic treatment, "This is something of a fraud, considering that the entire structure of analysis is built on the real number system." (p. 10) After proving the least upper bound property and some allied facts, cuts are not used in the rest of the book.

- Renteln, Paul; Dundes, Alan (January 2005). "Foolproof: A Sampling of Mathematical Folk Humor" (PDF). Notices of the AMS. 52 (1): 24–34. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 February 2009. Retrieved 3 May 2009.

- Richman, Fred (December 1999). "Is 0.999... = 1?". Mathematics Magazine. 72 (5): 396–400. doi:10.2307/2690798. JSTOR 2690798. Free HTML preprint: Richman, Fred (June 1999). "Is 0.999... = 1?". Archived from the original on 2 September 2006. Retrieved 23 August 2006. Note: the journal article contains material and wording not found in the preprint.

- Robinson, Abraham (1996). Non-standard Analysis (Revised ed.). Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-04490-3. JSTOR j.ctt1cx3vb6.

- Rosenlicht, Maxwell (1985). Introduction to Analysis. Dover. ISBN 978-0-486-65038-8. This book gives a "careful rigorous" introduction to real analysis. It gives the axioms of the real numbers and then constructs them (pp. 27–31) as infinite decimals with 0.999... = 1 as part of the definition.

- Rudin, Walter (1976) . Principles of Mathematical Analysis (3e ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-054235-8.

- A textbook for an advanced undergraduate course. "Experience has convinced me that it is pedagogically unsound (though logically correct) to start off with the construction of the real numbers from the rational ones. At the beginning, most students simply fail to appreciate the need for doing this. Accordingly, the real number system is introduced as an ordered field with the least-upper-bound property, and a few interesting applications of this property are quickly made. However, Dedekind's construction is not omitted. It is now in an Appendix to Chapter 1, where it may be studied and enjoyed whenever the time is ripe." (p. ix)

- Shrader-Frechette, Maurice (March 1978). "Complementary Rational Numbers". Mathematics Magazine. 51 (2): 90–98. doi:10.2307/2690144. JSTOR 2690144.

- Smith, Charles; Harrington, Charles (1895). Arithmetic for Schools. Macmillan. p. 115. ISBN 978-0-665-54808-6. Retrieved 4 July 2011.

- Sohrab, Houshang (2003). Basic Real Analysis. Birkhäuser. ISBN 978-0-8176-4211-2.

- Stewart, Ian (2009). Professor Stewart's Hoard of Mathematical Treasures. Profile Books. ISBN 978-1-84668-292-6.

- Stewart, James (1999). Calculus: Early transcendentals (4e ed.). Brooks/Cole. ISBN 978-0-534-36298-0.

- This book aims to "assist students in discovering calculus" and "to foster conceptual understanding". (p. v) It omits proofs of the foundations of calculus.

- Stillwell, John (1994), Elements of Algebra: Geometry, Numbers, Equations, Springer, ISBN 9783540942900

- Tall, David; Schwarzenberger, R. L. E. (1978). "Conflicts in the Learning of Real Numbers and Limits" (PDF). Mathematics Teaching. 82: 44–49. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 May 2009. Retrieved 3 May 2009.

- Tall, David O. (1976). "Conflicts and Catastrophes in the Learning of Mathematics" (PDF). Mathematical Education for Teaching. 2 (4): 2–18. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 March 2009. Retrieved 3 May 2009.

- Tall, David (2000). "Cognitive Development in Advanced Mathematics Using Technology" (PDF). Mathematics Education Research Journal. 12 (3): 210–230. Bibcode:2000MEdRJ..12..196T. doi:10.1007/BF03217085. S2CID 143438975. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 May 2009. Retrieved 3 May 2009.

- Tao, Terence (2012). Higher order Fourier analysis (PDF). American Mathematical Society.

- Tao, Terence (2003). "Math 131AH: Week 1" (PDF). Honors Analysis. UCLA Mathematics. Retrieved 23 May 2024.

- Wallace, David Foster (2003). Everything and more: a compact history of infinity. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-00338-3.

- Eisenmann, Petr (2008). "Why is not true that 0.999 . . . < 1?" (PDF). The Teaching of Mathematics. 11 (1): 38.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link)

Further reading

- Beswick, Kim (2004). "Why Does 0.999... = 1?: A Perennial Question and Number Sense". Australian Mathematics Teacher. 60 (4): 7–9.

- Burkov, S. E. (1987). "One-dimensional model of the quasicrystalline alloy". Journal of Statistical Physics. 47 (3/4): 409–438. Bibcode:1987JSP....47..409B. doi:10.1007/BF01007518. S2CID 120281766.

- Burn, Bob (March 1997). "81.15 A Case of Conflict". The Mathematical Gazette. 81 (490): 109–112. doi:10.2307/3618786. JSTOR 3618786. S2CID 187823601.

- Calvert, J. B.; Tuttle, E. R.; Martin, Michael S.; Warren, Peter (February 1981). "The Age of Newton: An Intensive Interdisciplinary Course". The History Teacher. 14 (2): 167–190. doi:10.2307/493261. JSTOR 493261.

- Choi, Younggi; Do, Jonghoon (November 2005). "Equality Involved in 0.999... and (-8)1/3". For the Learning of Mathematics. 25 (3): 13–15, 36. JSTOR 40248503.

- Choong, K. Y.; Daykin, D. E.; Rathbone, C. R. (April 1971). "Rational Approximations to π". Mathematics of Computation. 25 (114): 387–392. doi:10.2307/2004936. JSTOR 2004936.

- Edwards, B. (1997). "An undergraduate student's understanding and use of mathematical definitions in real analysis". In Dossey, J.; Swafford, J.O.; Parmentier, M.; Dossey, A.E. (eds.). Proceedings of the 19th Annual Meeting of the North American Chapter of the International Group for the Psychology of Mathematics Education. Vol. 1. Columbus, OH: ERIC Clearinghouse for Science, Mathematics and Environmental Education. pp. 17–22.

- Eisenmann, Petr (2008). "Why is it not true that 0.999... < 1?" (PDF). The Teaching of Mathematics. 11 (1): 35–40. Retrieved 4 July 2011.

- Ferrini-Mundy, J.; Graham, K. (1994). Kaput, J.; Dubinsky, E. (eds.). "Research in calculus learning: Understanding of limits, derivatives and integrals". MAA Notes: Research Issues in Undergraduate Mathematics Learning. 33: 31–45.

- Gardiner, Tony (June 1985). "Infinite processes in elementary mathematics: How much should we tell the children?". The Mathematical Gazette. 69 (448): 77–87. doi:10.2307/3616921. JSTOR 3616921. S2CID 125222118.

- Monaghan, John (December 1988). "Real Mathematics: One Aspect of the Future of A-Level". The Mathematical Gazette. 72 (462): 276–281. doi:10.2307/3619940. JSTOR 3619940. S2CID 125825964.

- Núñez, Rafael (2006). "Do Real Numbers Really Move? Language, Thought, and Gesture: The Embodied Cognitive Foundations of Mathematics". 18 Unconventional Essays on the Nature of Mathematics. Springer. pp. 160–181. ISBN 978-0-387-25717-4. Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 4 July 2011.

- Przenioslo, Malgorzata (March 2004). "Images of the limit of function formed in the course of mathematical studies at the university". Educational Studies in Mathematics. 55 (1–3): 103–132. doi:10.1023/B:EDUC.0000017667.70982.05. S2CID 120453706.

- Sandefur, James T. (February 1996). "Using Self-Similarity to Find Length, Area, and Dimension". The American Mathematical Monthly. 103 (2): 107–120. doi:10.2307/2975103. JSTOR 2975103.

- Sierpińska, Anna (November 1987). "Humanities students and epistemological obstacles related to limits". Educational Studies in Mathematics. 18 (4): 371–396. doi:10.1007/BF00240986. JSTOR 3482354. S2CID 144880659.

- Starbird, Michael; Starbird, Thomas (March 1992). "Required Redundancy in the Representation of Reals". Proceedings of the American Mathematical Society. 114 (3): 769–774. doi:10.1090/S0002-9939-1992-1086343-5. JSTOR 2159403.

- Szydlik, Jennifer Earles (May 2000). "Mathematical Beliefs and Conceptual Understanding of the Limit of a Function". Journal for Research in Mathematics Education. 31 (3): 258–276. doi:10.2307/749807. JSTOR 749807.

- Tall, David O. (2009). "Dynamic mathematics and the blending of knowledge structures in the calculus". ZDM Mathematics Education. 41 (4): 481–492. doi:10.1007/s11858-009-0192-6. S2CID 14289039.

- Tall, David O. (May 1981). "Intuitions of infinity". Mathematics in School. 10 (3): 30–33. JSTOR 30214290.

External links

Listen to this article (50 minutes)- .999999... = 1? from Cut-the-Knot

- Why does 0.9999... = 1 ?

- Proof of the equality based on arithmetic from Math Central

- David Tall's research on mathematics cognition

- What is so wrong with thinking of real numbers as infinite decimals?

- Theorem 0.999... on Metamath

| Real numbers | |

|---|---|

that is less than 1, the sequence 0.9, 0.99, 0.999, and so on will eventually reach a number larger than

that is less than 1, the sequence 0.9, 0.99, 0.999, and so on will eventually reach a number larger than  nines after the decimal point. Thus 0.(9)1 = 0.9, 0.(9)2 = 0.99, 0.(9)3 = 0.999, and so on. One has 1 − 0.(9)1 = 0.1 =

nines after the decimal point. Thus 0.(9)1 = 0.9, 0.(9)2 = 0.99, 0.(9)3 = 0.999, and so on. One has 1 − 0.(9)1 = 0.1 =  , 1 − 0.(9)2 = 0.01 =

, 1 − 0.(9)2 = 0.01 =  , and so on; that is, 1 − 0.(9)n =

, and so on; that is, 1 − 0.(9)n =  for every

for every  .

.

, then 1 −

, then 1 −  = 0.333..., so, ignoring all essential subtleties, "multiplying" this identity by 3 gives 1 = 0.999.... He further says that this argument is unconvincing, because of an unresolved ambiguity over the meaning of the

= 0.333..., so, ignoring all essential subtleties, "multiplying" this identity by 3 gives 1 = 0.999.... He further says that this argument is unconvincing, because of an unresolved ambiguity over the meaning of the

< 1, then:

< 1, then:

and common ratio

and common ratio  , the theorem makes short work of the question:

, the theorem makes short work of the question:

This proof appears as early as 1770 in

This proof appears as early as 1770 in  ,

,  ,

,  , ...) has the value

, ...) has the value  becomes arbitrarily small as

becomes arbitrarily small as  The first two equalities can be interpreted as symbol shorthand definitions. The remaining equalities can be proven. The last step, that 10 approaches 0 as

The first two equalities can be interpreted as symbol shorthand definitions. The remaining equalities can be proven. The last step, that 10 approaches 0 as  ), is often justified by the

), is often justified by the  ,

,  ,

,  , ..., and one writes

, ..., and one writes

,

,  ,

,  ... to be the least upper bound of the set of approximants

... to be the least upper bound of the set of approximants  , .... One can then show that this definition (or the nested intervals definition) is consistent with the subdivision procedure, implying 0.999... = 1 again.

, .... One can then show that this definition (or the nested intervals definition) is consistent with the subdivision procedure, implying 0.999... = 1 again.  such that

such that

with

with  and

and  . This implies

. This implies

and thus

and thus

by the definition above, every element of 1 is also an element of 0.999..., and, combined with the proof above that every element of 0.999... is also an element of 1, the sets 0.999... and 1 contain the same rational numbers, and are therefore the same set, that is, 0.999... = 1.

by the definition above, every element of 1 is also an element of 0.999..., and, combined with the proof above that every element of 0.999... is also an element of 1, the sets 0.999... and 1 contain the same rational numbers, and are therefore the same set, that is, 0.999... = 1.

is defined as the absolute value

is defined as the absolute value  , where the absolute value

, where the absolute value  is defined as the maximum of

is defined as the maximum of  and

and  , thus never negative. Then the reals are defined to be the sequences of rationals that have the Cauchy sequence property using this distance. That is, in the sequence

, thus never negative. Then the reals are defined to be the sequences of rationals that have the Cauchy sequence property using this distance. That is, in the sequence  there is an

there is an  such that

such that  for all

for all  ; the distance between terms becomes smaller than any positive rational.

; the distance between terms becomes smaller than any positive rational.

and

and  are two Cauchy sequences, then they are defined to be equal as real numbers if the sequence

are two Cauchy sequences, then they are defined to be equal as real numbers if the sequence  has the limit 0. Truncations of the decimal number

has the limit 0. Truncations of the decimal number  has a limit 0. Considering the

has a limit 0. Considering the  , it must therefore be shown that

, it must therefore be shown that

This can be proved by the

This can be proved by the  expression has a counterpart with repeated trailing digits equal to

expression has a counterpart with repeated trailing digits equal to  between 1 and 2, there are uncountably many base-

between 1 and 2, there are uncountably many base- = 0.111... = 1.111....

= 0.111... = 1.111.... = 0.142857 and 142 + 857 = 999.

= 0.142857 and 142 + 857 = 999. = 0.01369863 and 0136 + 9863 = 9999.

= 0.01369863 and 0136 + 9863 = 9999. ... is a positive integer, then it must be 0.999..., which is then the source of the 9s in the theorem. Investigations in this direction can motivate such concepts as

... is a positive integer, then it must be 0.999..., which is then the source of the 9s in the theorem. Investigations in this direction can motivate such concepts as  is given the usual representation of 0.2 or 0.2000..., since it lies to the right of the first deletion and the left of every deletion thereafter. The point

is given the usual representation of 0.2 or 0.2000..., since it lies to the right of the first deletion and the left of every deletion thereafter. The point  , multiplication by 10, and limits, and it alludes to Cauchy sequences as well.

, multiplication by 10, and limits, and it alludes to Cauchy sequences as well.

indexed by the

indexed by the  = 0.999...;...999000..., with last digit 9 at infinite

= 0.999...;...999000..., with last digit 9 at infinite  , satisfies a strict inequality

, satisfies a strict inequality  . Accordingly, an alternative interpretation for "zero followed by infinitely many 9s" could be

. Accordingly, an alternative interpretation for "zero followed by infinitely many 9s" could be

All such interpretations of "0.999..." are infinitely close to 1.

All such interpretations of "0.999..." are infinitely close to 1.  , where

, where  is the first

is the first  , but the first representation corresponds to the binary tree path LRLRLLL..., while the second corresponds to the different path LRLLRRR....

, but the first representation corresponds to the binary tree path LRLRLLL..., while the second corresponds to the different path LRLLRRR....

", which is the set of

", which is the set of  he allows both the cut (

he allows both the cut ( ,

,  -adic numbers

-adic numbers , than it is to 1. The

, than it is to 1. The