This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Shakar Shapour (talk | contribs) at 15:54, 17 October 2024. The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 15:54, 17 October 2024 by Shakar Shapour (talk | contribs)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| Seyîd Riza | |

|---|---|

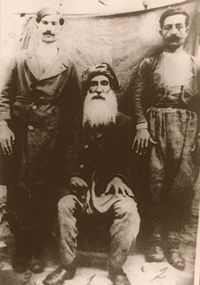

Seyid Riza before 1938 Seyid Riza before 1938 | |

| Born | 1863 Lertik, Sanjak of Dersim, Ottoman Empire |

| Died | November 1937 (aged 74) Elazığ, Turkey |

| Cause of death | Execution by hanging |

| Nationality | Kurdish |

| Occupation | Tribal leader of the Hesenan Kurds |

| Known for | Executed for being one of the leaders of the Dersim rebellion |

Seyid Riza (Template:Lang-ku, 1863 – 15 November 1937) was an Alevi Kurdish political leader of Dersim, tribal leader of the Hesenan tribe, and a religious figure and the leader of the Dersim rebellion.

Seyid Riza granted protection to the leaders of the Koçgiri rebellion. After the establishment of the Turkish Republic in 1923, Seyid Riza was a constant concern for the Turkish government as he remained largely autonomous and beyond the control of authorities in the Dersim region. Following the passing of the Resettlement law in 1934, and the Tunceli Law in 1935, Seyid Riza began to oppose the Turkish authorities. The Tunceli Law prescribed that the Dersim region would become Tunceli province and placed it under military control of the Fourth Inspectorate General.

Seyid Riza led an rebellion which occurred in 1937/38 in the Dersim region, which roughly corresponds to today's Tunceli and Bingöl provinces, and was led by the elites of the so-called Dersim Kurds, who were both Kurmanji and Zaza speakers. Seyid Riza was considered as the leader. Seyid Riza’s uprising led according to Turkish state reports, ten percent of the total 30,000 to 70,000 residents of the affected parts of the historic Dersim killed in the clashes.

Early life

Riza was born in Lirtik, a village in the Ovacık district, as the youngest of four sons of Seyid Ibrahim, leader of the Hesenan tribe. Seyid Riza succeeded his father as leader after Ibrahim's death in accordance with his will.

After his father's death, he received leadership of his tribe and the title of Sayyid سیّد (Arabic for Lord). This title was only given to the (supposedly) direct descendants of the Prophet Muhammad. Seyid Riza then lived in Akhdat, a small village on the slopes in the Munzur mountain range.

World War I

During the First World War he led the tribe on the side of the Ottoman Empire against the Russians. Specially in 1917, western tribes of Dersim were also enrolled as Ottoman troops. Meanwhile, as a result of the Erzincan Armistice with the Russians, there was no conflict in 1917. In February 1918, with the withdrawal of Russian troops to Erzurum (due to the October Revolution), the Ottoman army decided to enter Erzincan to overthrow the Erzincan Council. According to Kâzım Karabekir, 919 people were registered as militia by the state in the eastern side of Dersim and 2567 people from the western side. Approximately 750 of the Western Dersim militia entered Erzincan on February 13, 1918, under the command of Halit Pasha. He also became the commander of Seyit Rıza's Second Sheikh Hasananlı Regiment and commanded a regiment with four battalions. Dersim militia under the command of Deli Halit Pasha, together with Seyid Riza, expelled the Russians and Armenians from Erzincan and the war ended with success. After the Russians retreated, the people of Dersim were rewarded. Seyid Riza was also rewarded and appointed as Erzincan Provincial Administration Member. Sabit Bey, one of the Erzincan governors of the period, states in a letter about Seyid Riza that "so far he has served us with religion and honor."

Seyid Riza reportedly did not always comply with the demands placed upon him by the Ottomans, for instance refusing to hand over for deportation Armenians in his area of influence during the Armenian genocide.

Seyid Riza‘s father led his tribe on the side of the state during Sheikh Said rebellion in 1925.

Dersim rebellion

Background

The traditional community and tribal structures and tribal law were still largely intact in Turkish Kurdistan around the 1930s. The state's influence was small. There were around 100 small tribes whose leaders fought for dominance and sometimes fought bloody feuds in which the army sometimes got involved. The population lived mainly from agriculture and livestock breeding, mostly in the form of semi-nomadic transhumance. Population was mostly poor and not well educated. Kurdish nationalism was particularly widespread among the well-educated sons of leading families. The feudal conditions stood in contrast to the modernization efforts of the young Turkish Republic. The state elite sought to bring “civilization” (medeniyet) to the region. They wanted to build roads, schools and factories and free the population from the tutelage of the Alevi religious leaders, the Aghas, and the feudal lords. Dersim symbolized the backwardness of the Ottoman Empire, which needed to be overcome.

On June 21, 1934, the so-called Settlement Law (İskân Kanunu) came into force with publication in the Official Newspaper of Turkey. The aim of the law was to Turkishize the population, which state representatives considered to be the “original Turks” anyway ,a view and politic in which Seyid Riza was heavily against it. Dersim was the first area where the law was to apply. 1936, in the Turkish press and also by members of the government, Dersim was described as a 'disease' (hastalık) and 'disaster' (belâ). The power of the Aghas, including Seyid Riza, must be broken. Economic measures should be introduced, roads and schools should be built and the population should be “warmed up” to the state. The residents became “alienated” from Turkishness, some of them forgot their language and began to think of themselves as Kurds. So the ethnic structure stood in contrast to the state's understanding of nationality and aspirations for unity. Kurds and Zazas were seen as a potential threat to state unity.

The Rebellion (1937)

During the Newroz festivities of March 1937, Seyid Riza called for a rebellion against the Turkish government. The rebellion was suppressed by the Turkish military by September of the same year. On September 12, 1937, he was arrested with seventy-two other rebels on their way to negotiations with the Turkish government.

Some tribes reacted violently to the resettlement law's regulations and Turkification efforts and the increasing military presence, which they viewed as an attack on their de facto sovereignty. The Haydaran and Demenan tribes burned down a police station and a wooden bridge and destroyed telephone lines on the night of March 21, 1937. This was preceded by several incidents of violence against villagers, cases of rape by Turkish soldiers and the killing of Turkish soldiers. The state immediately brought in troops from other provinces in the region, made initial arrests and attempted to confiscate weapons. Elazığ became an air force base. The 2nd Squadron initially provided seven aircraft. Seyid Rıza was suspected of initiating the riots. The suspicion may have been the result of a denunciation of Seyid Rıza's local enemies.

Six days later, Seyid Riza and his insurgents attacked Tunceli‘s guardhouse. More raids followed. In early May 1937, insurgents laid an ambush and killed ten officers and 50 soldiers. Traces of torture and the disfigurement of the corpses caused great outrage in Turkey.

When the air force began bombing villages, Seyid Riza sent a delegation to negotiate at the Turkish headquarters in Elazığ. Bre İbrahim, a son of Seyid Riza, also went to the Turkish headquarters for negotiations and was killed on the way back by members of the feuding Kurdish pro gouverment Kirgan tribe. Riza demanded local autonomy and the punishment of the murderers. Governor Alpdoğan refused and again demanded the surrender of all weapons. On April 26, Seyid Riza Rıza carried out a reprisal attack on the Kirgan tribe in north-eastern part of Tunceli province, the center of this tribe.

Capture

Events escalated in the summer. The insurgents raided barracks and guards and attempted to blow up bridges in Mazgirt and Pertek. Old disputes and blood feuds flared up among the tribes. There were changing coalitions. In September, Riza‘s situation became hopeless. His second wife named Bese, another son and a large number of residents of his village were killed by soldiers. Disappointed and apparently also under pressure from his own tribe, Seyid Riza surrendered. He was arrested with 50 followers, brought to trial, convicted after a four-day trial and immediately executed in mid-November.

The trial and his execution

Seyid Riza was tried and sentenced after a trial that lasted two weeks and consisted of three hearings. The final sentence was passed on a Saturday, a highly unusual day for a court to be in session at that time. This abnormal course of events was due to Mustafa Atatürk's impending visit to the region and the local government's fear that the Turkish head of state would be petitioned to grant Riza amnesty. The chief judge of the court at first refused to render his final verdict on a Saturday, citing a lack of electricity at night and the absence of a hangman. After local authorities arranged to light the courtroom with automobile headlights and found a hangman, everything was set for the passing of the sentence. Eleven men, including Seyid Riza himself, his son Uşene Seyid, Aliye Mırze Sili, Cıvrail Ağa, Hesen Ağa, Fındık Ağa, Resik Hüseyin and Hesene İvraime Qıji were sentenced to death. Four death sentences were commuted to 30 years imprisonment. Seyid Riza was 74 years old when the sentence was announced making him legally ineligible to be executed by hanging. The court, however, accepted that he was 54, not 74. Riza did not understand his sentence until he saw the gallows.

His final moments were witnessed by İhsan Sabri Çağlayangil:

'Seyid Riza understood the situation immediately when he saw the gallows. "You will hang me," he said. Then he turned to me and asked: "did you come from Ankara to hang me?" We exchanged glances. It was the first time I faced a man who was going to be hanged. He flashed a smile at me. The prosecutor asked whether he wanted to pray. He didn't. We asked for his last words. "I have forty liras and a watch. You will give them to my son." he said. We brought him to the square. It was cold and deserted. However, Seyid Riza addressed the silence and emptiness as though the square were full of people. "We are the sons of Karbala. We are blameless. It is shameful. It is cruel. It is murder!" he said. I had goosebumps. The old man walked briskly to the gallows and shoved the hangman out of the way. He put the rope around his neck and kicked the chair, executing himself. However, it is hard to feel sorry for a man who hanged a boy as young as his own son. When Seyid Riza was hanged his son's voice could be heard from the side: "I'll be your slave! I'll be your muse! Feel some pity for my youth, don't kill me!"'

A total of 58 people consisted of surrenderd forces, and other Kurdish tribal leaders stood trial. Some of the following people were executed with Riza were:

- Resik Hüseyin, son of Rıza

- Seyit Haso, leader of the Shekhani tribe

- Fındık, son of Kamer, the leader of the Yusufan tribe

- Hasan, son of Cebrail, leader of the Demenan tribe

- Hasan, son of Ulikiye from the Kureyşan tribe

- Ali, son of Mirzali Beg, one of the leaders of the uprising

The bodies of those executed were displayed in Elazığ, then burned and buried in an unknown location. Four of the eleven people sentenced to death had their death sentences commuted to prison sentences of 30 years each because they were over the age limit. Fourteen defendants were acquitted, the others were sentenced to various prison terms.

Aftermath

In a letter explaining the reason for the Dersim rebellion to British foreign secretary Anthony Eden, Seyid Riza is said to have written the following:

"The government has tried to assimilate the Kurdish people for years, oppressing them, banning publications in Kurdish, persecuting those who speak Kurdish, forcibly deporting people from fertile parts of Kurdistan to uncultivated areas of Anatolia where many have perished. The prisons are full of non-combatants, intellectuals are shot, hanged or exiled to remote places. Three million Kurds demand to live in freedom and peace in their own country."

A document, submitted to the Presidency with the signature of Minister of Interior Şükrü Kaya on 18 October 1937, states that this letter was in fact written, and signed, by a person named Yusuf in Syria.

It is indeed very likely that this letter was not sent by Seyid Riza but by Nuri Dersimi, a Kurdish nationalist revolutionary from Dersim who took refuge in Syria. The letter was written in a failed attempt to get support for the Kurdish nationalist cause from Western powers. Turkish authorities used the letter as evidence that Seyid Riza rebelled against the state but never proved that the letter was in fact written by him. English archives supposedly show that the letter was signed by Nuri Dersimi.

His grave

Seyid Riza was buried in secret and the whereabouts of his grave remain unknown. There is an ongoing campaign to find the burial site. During a visit to Tunceli, president Abdullah Gül was asked to disclose the location of the grave where Seyid Riza and his companions were laid to rest after their execution. "This is not a difficult issue, it is in the state archives." said Hüseyin Aygün a lawmaker from Dersim/Tunceli, representing the province in Turkish parliament for opposition party CHP.

Memorial

In 2010 a statue of Seyid Riza was erected at one of the entrances to Tunceli and the park around the statue was named after him.

See also

References

- "Partiyeke Tirkiyê dixwaze peykerê Seyîd Riza yê li Dêrsimê were rakirin!". Peyama Kurd (in Kurdish). Retrieved 22 December 2019.

- "بۆچی لە ڕۆژی لەسێدارەدانیدا ئەتاتورک چاوی بە سەید ڕەزای دەرسیم کەوت؟" (in Kurdish). Retrieved 14 August 2019.

- Donmez-Colin, Gonul (2019-07-19). Women in the Cinemas of Iran and Turkey: As Images and as Image-Makers. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-351-05029-6.

- Meiselas, Susan; Bruinessen, Martin van; Whitley, A. (1997). Kurdistan: In the Shadow of History. Random House. p. 150. ISBN 978-0-679-42389-8.

- Altan Tan, Kürt sorunu, Timas Basim Ticaret San As, 2009, ISBN 978-975-263-884-6, p. 28.

- Celal Sayan, La construction de l'état national turc et le mouvement national kurde, 1918–1938, Volume 1, 2002, Presses universitaires du septentrion, p. 680.

- Olson 1989, p. 120. sfn error: no target: CITEREFOlson1989 (help)

- "Who's who in Politics in Turkey" (PDF). Heinrich Böll Stiftung. pp. 235–236. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 November 2019. Retrieved 22 December 2020.

- Törne, Annika (5 November 2019). Dersim – Geographie der Erinnerungen: Eine Untersuchung von Narrativen über Verfolgung und Gewalt (in German). Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. p. 78. ISBN 978-3-11-062771-8.

- Kieser, Hans-Lukas (2016-01-19). "Dersim Massacre, 1937-1938 | Sciences Po Mass Violence and Resistance - Research Network". dersim-massacre-1937-1938.html. Retrieved 2020-12-22.

- Gunter, Michael M. (1994). "The Kurdish factor in Turkish foreign politics". Journal of Third World Studies. 11 (2): 444. ISSN 8755-3449. JSTOR 45197497 – via JSTOR.

- Mehmed S. Kaya (15 June 2011). The Zaza Kurds of Turkey: A Middle Eastern Minority in a Globalised Society. I.B.Tauris. pp. 64–. ISBN 978-1-84511-875-4.

was led specifically by the Zaza population and received almost full support in the entire Zaza region and some of the neighbouring Kurmanji-dominated regions

- Deniz, Dilşa (2020-09-04). "Re-assessing the Genocide of Kurdish Alevis in Dersim, 1937-38". Genocide Studies and Prevention. 14 (2). doi:10.5038/1911-9933.14.2.1728</p> (inactive 7 May 2024). ISSN 1911-0359.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of May 2024 (link) - "1938 Dersim: Bir belge de Nazımiye Nüfus Müdürlüğü'nden!". Baskın Oran (in Turkish). 2014-08-28. Retrieved 2024-05-06.

- Törne, Annika (2019-11-05). Dersim – Geographie der Erinnerungen: Eine Untersuchung von Narrativen über Verfolgung und Gewalt. De Gruyter. doi:10.1515/9783110630213. ISBN 978-3-11-063021-3.

- ^ "Who's who in Politics in Turkey" (PDF). Heinrich Böll Stiftung. pp. 235–236. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 November 2019. Retrieved 22 December 2020.

- Olson 1989, pp. 48–49. sfn error: no target: CITEREFOlson1989 (help)

- ^ "Dersim'in işgalci Ruslar'a karşı savaşının belgeleri var". web.archive.org. 2017-07-04. Retrieved 2024-10-14.

- Kazım Karabekir, Erzincan ve Erzurum’un Kurtuluşu, Koşkun Basımevi, 1939,

- ^ Olson 1989, pp. 97–98. sfn error: no target: CITEREFOlson1989 (help)

- Olson 1989, p. 102. sfn error: no target: CITEREFOlson1989 (help)

- Olson 1989, p. 96. sfn error: no target: CITEREFOlson1989 (help)

- Olson 1989, p. 45. sfn error: no target: CITEREFOlson1989 (help)

- ^ Jwaideh, Wadie (2006). The Kurdish National Movement: Its Origins and Development. Syracuse University Press. p. 215.

- "Seyit Rıza Teslim oldu". Kurun (in Turkish). September 13, 1937. p. 1.

- (Olson 2000, p. 113) harv error: no target: CITEREFOlson2000 (help)

- ^ (Olson 2000, p. 117) harv error: no target: CITEREFOlson2000 (help)

- Abdulla, Mufid (2007-10-26). "The Kurdish issue in Turkey need political solution". Kurdish Media. Archived from the original on 2007-12-28. Retrieved 2008-08-01.

- "HÜSEYİN AKAR » 05- Seyit Rıza". Archived from the original on 17 November 2011. Retrieved 22 November 2011.

- "Seyit Rıza'nın kabul edilmeyen son isteği; "Beni oğlumdan önce asın! » Cafrande Kültür Sanat". 4 May 2018.

- "Dersim'i Çağlayangil ve Batur'dan Dinliyoruz - bianet".

- McDowall, David. A Modern History of the Kurds, page 208. I.B. Tauris, 2004.

- "Seyit Rıza'nın 75 yıl sonra ortaya çıkan mektupları VİDEO-GALERİ". www.haberturk.com (in Turkish). 10 May 2012. Retrieved 2019-11-06.

- The Upper Echelons of the State in Dersim, by Abdullah Kiliç and Ayça Örer, published (in Turkish) in Radikal paper, 20–24 November 2011. An English translation: http://www.timdrayton.com/a55.html

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 April 2012. Retrieved 22 November 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "President Gül Faces Demands from Tunceli - Erol Önderoğlu - english".

- Hirsch, Helga (2011-11-19). "Ein (fast) vergessenes Massaker". Retrieved 2019-04-03.

- "Victims of Dersim genocide remembered". ANF News. Retrieved 2019-04-03.

Bibliography

- Ayata, Bilgin; Hakyemez, Serra (2013). "The AKP's engagement with Turkey's past crimes: an analysis of PM Erdoğan's "Dersim apology"". Dialectical Anthropology. 37 (1): 131–143. doi:10.1007/s10624-013-9304-3. ISSN 1573-0786. S2CID 144503079.

- Deniz, Dilşa (2020). "Re-assessing the Genocide of Kurdish Alevis in Dersim, 1937-38". Genocide Studies and Prevention. 14 (2): 20–43. doi:10.5038/1911-9933.14.2.1728. ISSN 1911-0359.

- Ilengiz, Çiçek (2019). "Erecting a Statue in the Land of the Fallen: Gendered Dynamics of the Making of Tunceli and Commemorating Seyyid Rıza in Dersim". L'Homme. 30 (2): 75–92. doi:10.14220/lhom.2019.30.2.75. S2CID 213908434.

- Erbal, Ayda (2015). "The Armenian Genocide, AKA the Elephant in the Room". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 47 (4): 783–790. doi:10.1017/S0020743815000987. ISSN 0020-7438. JSTOR 43998041. S2CID 162834123.

Further reading

- Ashly, Jaclynn (12 January 2021). "The Massacre in Dersim Still Haunts Kurds in Turkey". Jacobin. Retrieved 9 February 2021.

- Boztas, Özgür Inan. "Did a Genocide Take Place in the Dersim Region of Turkey in 1938?." Strassler Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies (2015): 1–20.

- CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of May 2024

- 1863 births

- 1937 deaths

- People from Tunceli

- Kurdish Alevis

- Kurdish revolutionaries

- Executed Kurdish people

- Executed revolutionaries

- People executed for treason against Turkey

- People executed by Turkey by hanging

- 20th-century executions for treason

- People of the Dersim rebellion