This is an old revision of this page, as edited by 194.38.172.194 (talk) at 16:11, 8 November 2024 (Undid revision 1256167131 by DonBeroni (talk) Please keep the extended version. Please try to read before undoing....). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 16:11, 8 November 2024 by 194.38.172.194 (talk) (Undid revision 1256167131 by DonBeroni (talk) Please keep the extended version. Please try to read before undoing....)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)

| Battle of Pacocha | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Huáscar uprising of 1877 | |||||||

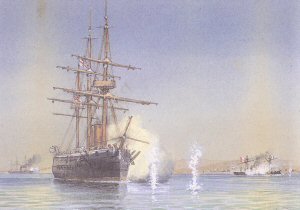

The Naval Combat in the Pacific between HMS SHAH and HMS AMETHYST and the Peruvian Rebel Ironclad Turret Ram HUASCAR on May 29th 1877, William Frederick Mitchell | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

1 frigate 1 corvette 2 artillery boats | 1 monitor | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Unknown wounded |

1 killed Unknown wounded | ||||||

The Battle of Pacocha was a naval battle that took place on 29 May 1877 between the rebel-held Peruvian monitor Huáscar and the British ships HMS Shah and HMS Amethyst. The vessels did not inflict significant damage on each other, however the battle is notable for seeing the first combat use of the self-propelled torpedo.

Background

In May 1877, Nicolás de Piérola, former Minister of Finance, initiated an attempt to overthrow then-President Mariano Ignacio Prado. As part of this coup attempt, on 6 May two of his supporters, Colonel Lorranaga and Major Echenique, boarded Huáscar at the port of Callao while the captain and executive officer were ashore. Officers remaining on the ship were part of the plot and persuaded the crew to join their cause. Now in rebel hands, Huáscar put to sea with Luis Germán Astete in command. Other Peruvian naval ships present in the port, such as Atahualpa, were in a state of disrepair and unable to pursue.

The rebels used the ship to harass commercial shipping, especially off Callao, the main commercial port of Peru. However, after she forcibly boarded some British merchant ships, British authorities sent HMS Shah and HMS Amethyst, under command of Rear Admiral Algernon de Horsey, to capture the vessel, with authorization and reward offered by the Peruvian government of Mariano Ignacio Prado.

On May 16, it appeared in the port of Antofagasta, Bolivia, where he picked up Nicolás de Piérola, as Supreme Chief of Peru, and his entourage of followers..

Intimidation

The British squadron was in search of the Huáscar, when it sighted it on May 29, 1877 at 13:00. The Huáscar was heading for land when HMS Amethyst blocked its way and at 14:11 HMS Shah fired a cannon shot at it to put it in communication. Rear Admiral De Horsey sent Lieutenant Rainier to inform the commander of the Huáscar, Captain Astete, that he would seize the ship as a result of illegal acts that the Huáscar had committed against British subjects, ships and property, that he was not acting on behalf of the Peruvian government, that if the ship was handed over, the freedom of all on board would be respected and they would be disembarked in a neutral place, wherever the commander wished, but otherwise, the Huáscar would be treated as a pirate ship. Lieutenant Rainier returned with the reply that the President of Peru was on board, that the Huáscar had not committed any illegal act, and that they would not lower the flag.

Battle

Quilca and the Amethyst to Mollendo. At 19:00 the next day, May 30, the Amethyst went to Quilca and brought the news that the Huáscar was in Iquique , thither the British squadron was heading. At 20:00 on May 31, the torpedo boats were again detached when the Shah was 7 miles from Iquique, but the HMS Amethyst informed them that the Huáscar had already surrendered to the Peruvian squadron that was pursuing her, with which cannon fire and signal rockets were launched for the boats to return. On June 1, the British squadron met the Peruvian squadron and greeted each other.

The Shah then headed for Panama and the Amethyst for Valparaíso.

During the engagement the Shah fired 237 shells and the Amethyst 190, but none were effective because they were not Palliser shells , which at the time were the only ones that could pierce a ship's armour. The Shah 's 9- inch guns could pierce 9.5 inches of iron armour at a thousand yards, while the 7-inch guns could pierce 7.5 inches of iron armour at a thousand yards, while the 64- pounder guns could pierce 4.5 inches of armour at very close range, but the ranges during the engagement were between 100 and 2,000 yards, and because the British ships had to move to avoid being targeted by the Huascar 's shots , her shots were not accurate and powerful enough to cause damage.

The Huáscar was hit by about 60 shots, but none of them were serious due to the protection of its armor. A 9-inch shell pierced a 3.5-inch plate of armor above the waterline, killing the cornet Ruperto Béjar. Another 7-inch shell hit the revolving turret but only pierced 3 inches of the 5.5-inch armor. Because the Huáscar had no gunners, only young revolutionaries with no previous combat experience, no shots were hit, only a 40-pounder that hit the Shah 's mast, but the Huáscar was well steered, despite the fact that the British shells had cut the rudder guards, something that happened again in the naval battle of Angamos and that would be a serious problem in that confrontation.

Importance

This battle was the first and only time that a ship of the Peruvian fleet was able to emerge victorious in a battle against ships of the Royal Navy. Rear Admiral De Horsey was requested by the British Parliament following this incident, the news of which went around the world and filled the Peruvian sailors with pride, although in Great Britain the details of the battle were kept secret in order to maintain the reputation of the Royal Navy's invincibility against possible allies (France and Russia) and potential rivals (Germany).

It was important because it was the first time that a mobile Whitehead torpedo was used in combat, which was later used by the Russians during the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-78. On those occasions this torpedo was useless, because during the day it was easy to avoid them, as easy as the British ships avoided the Huascar 's ram . Months later, at night, the Russians would test the effectiveness of the self-propelled torpedo by sinking the Turkish steamer Intibah . The Huascar also tried to use mobile torpedoes during the Pacific War in 1879, but it was the Lay torpedo system , which was electrically guided by cable and was never successfully applied.

The first time it was successfully used against a warship, also in a night action, was in the Chilean Civil War of 1891, when the armored ship Blanco Encalada was sunk, after 5 torpedoes were launched at it, the last one hitting it. Paradoxically, the monitor Huáscar, already flying the Chilean flag, was a witness to that event.

The battle also proved the inefficiency of the English cruisers, even though they had a well-trained crew, which was overall superior to that of the Huáscar (837 men versus 179), an advantage in powerful cannons and attack from two flanks at once. The Huáscar would have defeated them with efficient gunners and not enthusiastic young rebels. It was demonstrated that it was necessary for these types of cruisers to have some armored protection, giving rise to the so-called "protected cruisers", although Chile and France were the first to have this type of ships.

In honor of the battle and the Peruvian victory, a submarine acquired by Peru from the United States was named Pacocha, which sank off the coast of Callao in 1988 after a collision with a Japanese fishing boat, the rescue of most of its crew being considered a miracle by the Catholic Church since the closing of the bulkheads due to the pressure of the water and the successful escape of its survivors by sheer lung power, without oxygen or special suits, all of which occurred in critical conditions, was considered a miracle, which was attributed to Maria de Jesus Crucificado Petkovic, being beatified by Pope John Paul II

References

- "Great Britain And Peru". The Times. No. 28960. London. 5 June 1877. p. 10.

- ^ Robert Stem (18 September 2008). Destroyer Battles: Epics of Naval Close Combat. Seaforth Publishing. p. 18. ISBN 978-1-84832-007-9.

- "The Huascar". The Times. No. 28968. 14 June 1877. p. 14.

External links

This article about a battle in British history is a stub. You can help Misplaced Pages by expanding it. |