This is an old revision of this page, as edited by BlkGeneral2000 (talk | contribs) at 14:05, 5 January 2025 (←Created page with '{{short description|1812 abolitionist movement in the Dominican Republic}} {{Infobox civil conflict | title = 1812 Mendoza and Mojarra Conspiracy | subtitle = | partof = The Slave Revolts in North America and Age of Revolution | image = Santo Domingo Map 1873.jpg | caption = Map of the Dominican capital, Santo Domingo, in 1873 | date = {{Start date|1812|08|}}; 213 years ago | place = Near Santo Domingo, Dominic...'). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 14:05, 5 January 2025 by BlkGeneral2000 (talk | contribs) (←Created page with '{{short description|1812 abolitionist movement in the Dominican Republic}} {{Infobox civil conflict | title = 1812 Mendoza and Mojarra Conspiracy | subtitle = | partof = The Slave Revolts in North America and Age of Revolution | image = Santo Domingo Map 1873.jpg | caption = Map of the Dominican capital, Santo Domingo, in 1873 | date = {{Start date|1812|08|}}; 213 years ago | place = Near Santo Domingo, Dominic...')(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) 1812 abolitionist movement in the Dominican Republic| 1812 Mendoza and Mojarra Conspiracy | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of The Slave Revolts in North America and Age of Revolution | |||

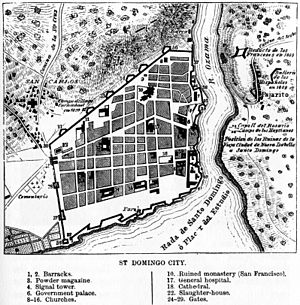

Map of the Dominican capital, Santo Domingo, in 1873 Map of the Dominican capital, Santo Domingo, in 1873 | |||

| Date | August 1812 (1812-08); 213 years ago | ||

| Location | Near Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic | ||

| Goals |

| ||

| Resulted in | Suppression of the revolt | ||

| Parties | |||

| |||

| Lead figures | |||

|

Pedro Seda, José Leocadio, Pedro Henríquez, and Marcos Manuel Caballero y Masot | |||

| Part of a series on |

| North American slave revolts |

|---|

Attack and capture of the Crête-à-Pierrot (Combat et prise de la Crête-à-Pierrot, March 1802) in the Haitian Revolution by Auguste Raffet, engraving by Ernest Hébert Attack and capture of the Crête-à-Pierrot (Combat et prise de la Crête-à-Pierrot, March 1802) in the Haitian Revolution by Auguste Raffet, engraving by Ernest Hébert |

| Context |

|

Before 1700

(Spanish Florida, victorious)

(Real Audiencia of Panama, New Spain, suppressed)

(Veracruz, New Spain, victorious)

(New Spain, suppressed)

(New Spain, suppressed)

|

|

18th century

(British Province of New York, suppressed)

(British Jamaica, victorious)

(British Chesapeake Colonies, suppressed)

(Louisiana, New France, suppressed) (Danish Saint John, suppressed)

(British Province of South Carolina, suppressed)

(British Province of New York, suppressed)

(British Jamaica, suppressed) (British Montserrat, suppressed)

(British Bahamas, suppressed)

(Louisiana, New Spain, suppressed) (Louisiana, New Spain, suppressed) (Dutch Curaçao, suppressed)

|

19th century

(Virginia, suppressed)

(St. Simons Island, Georgia, victorious)

(Virginia, suppressed) (Territory of Orleans, suppressed)

(Spanish Cuba, suppressed)

(Virginia, suppressed)

(British Barbados, suppressed)

(South Carolina, suppressed) (Cuba, suppressed) (Virginia, suppressed)

(British Jamaica, suppressed)

(off the Cuban coast, victorious)

(off the Southern U.S. coast, victorious) (Indian Territory, suppressed)

(Spanish Cuba, suppressed) (South Carolina, suppressed)

|

| Notable leaders |

The 1812 Mendoza and Mojarra Conspiracy was a slave movement that transpired during In Santo Domingo, (now Dominican Republic) in the heat of the proclamation of the Cadiz Constitution, in 1812. This movement, led by free blacks in the Dominican capital, Santo Domingo, sought to overthrew the Spanish government and declare the independence of Santo Domingo, with the intention of joining Haiti.

When the authorities refused to free the slaves and failed to enforce several provisions of the new liberal Spanish constitution of 1812 that granted Spanish nationality, (but not citizenship), to the children of freedmen and allowed slaves to purchase their freedom, there was a conspiracy of freedmen and slaves to eradicate slavery and join the Republic of Haiti. When discovered, its leaders were sentenced to death and their heads were displayed at various points around the capital. The other culprits were sentenced to prison and flogging. Pedro Seda, José Leocadio, Pedro Henríquez, and someone known only as Marcos were the ringleaders of this revolt.

The conspirators claimed to be fighting for the freedom that the General and Extraordinary Courts had recognized for slaves. This was the only movement with explicit links to the Constitution of Cadiz.

Context

In 1809, the Criollo leader, Juan Sánchez Ramírez, had successfully defeated the occupying French forces in Santo Domingo after his victory in the Spanish reconquest of Santo Domingo. With the capitulation of French governor, Joseph-David de Barquier, Sánchez Ramírez was sworn in as governor of the colony. However, from the very beginning, his popularity began to wane due to his belief that Santo Domingo's preservation was tied to Spain, who immediately reestablish control over the colony that same year. Ultimately, his rule was characterized by royalist by critics.

There were even strong disagreements and some confrontations between Sánchez Ramírez and his general advisor, José Núñez de Cáceres. While the former moved within the absolutist and conservative parameters that led him to govern Santo Domingo in an autarkic manner, severely punishing any infraction or suspicion of sedition, the tendencies of the latter were liberal and democratic. although, like Sánchez Ramírez, he did not think in abolishing slavery (or perhaps both judged that the existence of slaves was essential for the Dominican economy: without them survival would have been even more difficult in those days, although in reality the number of slaves was rather low existing slaves in Spanish Santo Domingo).

In February 1811, Sánchez Ramírez died. His authoritarian behavior, among other reasons, also gave rise to differences with some of those who had been his companions in the reconquest enterprise. Núñez de Cáceres remained at the head of the Government of Santo Domingo, who had tried to advise the Sánchez on certain changes that were surely considered too progressive and were not accepted by him. When Manuel Caballero was appointed as interim governor, Núñez continued in his positions as lieutenant governor, war auditor and general advisor. In a letter addressed by the latter to the then governor of Puerto Rico on February 22, 1811, he informed him of his arrival in Santo Domingo on January 18 of the same year, the beginning of the exercise of the aforementioned positions on the 28th and that due to the death of Sánchez Ramírez, on February 12, he assumed the political leadership and mayorship, in the interim the new governor was named. He expresses his desire to maintain and cultivate friendly relations as befits two neighboring governments, servants of the same king, and to provide mutual aid in case of need.

In March, Spain's first constitution, the Constitution of Cadiz would be passed. (This would become the thesis for the eventual separation of Santo Domingo from Spain). However, slavery still remained legal and laws that extended rights to free blacks would never be upheld. The general discontent among the population was not only due to the economic difficulties and shortages they suffered, but social and racial tensions emerged. The colonial prejudices that had persisted since the beginning of Spanish colonization would once again spread in society, and as such, further anti-Spanish plots would emerge.

Revolt

In August 1812, to the east of Santo Domingo, rebellions by people of color, slaves and freedmen, occurred on the haciendas of Mendoza and Mojarra. Pedro de Seda, Pedro Henríquez, Marcos, José Leocadio, Meas and Fragoso, among others, participated in the insurrections. According to historian Roberto Cassá, unlike the previous ones, with a political purpose and promoted by the urban petty bourgeoisie, this movement presented a social motivation, apparently unrelated to national independence. Its purpose was the abolition of slavery and the achievement of a series of measures in accordance with its class interests. They wanted to improve their legal and social situation. (Despite the decline of slavery in Santo Domingo, a mass of a few thousand slaves continued to exist). The rebels were part of the few plantations of the colonial bureaucratic aristocracy that were still exploited, with limited means and also poor performance, during the years of España Boba.

According to the authorities, the rebellion allegedly sought out a genocide of all whites. Although according to José María Morillas, a free black man and a witness to the events, he claims that the plot was aimed at “the freedom of his race and adherence to the Republic of Haiti.” In addition, to gain followers, they claimed that the brigadier of the black auxiliaries Gil Narciso came to the island as a legitimate governor to protect the interests of mulattoes and blacks. Gil Narciso appeared linked to the Aponte Conspiracy in Cuba, at the beginning of 1812. It was also said that they had the support of prominent mulatto and black officers in the Spanish Army. Some example include Pablo Alí, a former slave who fought in the Haitian Revolution of 1791, and Juan Mambí, a black officer who later deserted from the Spanish side and joined the future independence movements of what would later become the Dominican Republic, as well as in Cuba. (Hence the name, Mambises to refer to the Cuban independence guerrillas). However, there is little evidence of their participation in the conspiracy.

Suppression

The repression, achieved thanks to a denunciation, was very harsh. Pedro Seda, Pedro Hernández and Marcos were executed and their heads were displayed on the roads of Montegrande, Mojarra and at the entrance to the Enjaguador sugar mill. Days later, José Leocadio, the leader of the rebellion, Cañafístola, the Meas, Fragoso and others were arrested and tried. They were also punished with extreme rigor, to the point that after the sentence, "... the prisoners went to the scaffold, shrouded in bags and dragged to the tail of a donkey and their limbs dismembered and fried in tar...". According to historian José Gabriel García, others who were considered less dangerous were whipped and served sentences of temporary or perpetual hard labor, depending on the case.

Aftermath

Over the next five years, continued independence plots were discovered by the colonial authorities, who managed to disrupt the plans before they could fully materialize. It wouldn't be until 1821, when a renewed seperatist conspiracy, led by José Núñez de Cáceres, himself, would take fruit, resulting in the successful capitulation of the Spanish at the end of November 1821. However, the issue regarding slavery would cause great discontent, and plans to merge the independent Santo Domingo to Haiti once again emerged. This would reflect the climate of disunity between various factions, which existed in the Spanish part of the island in the days of its official submission to the metropolis.

See also

References

- Archivo General de Puerto Rico (AGPR): RG. 186: Records of the Spanish Governors of Puerto Rico. Political and Civil affairs. Cónsules: Santo Domingo, 1796-1858. Letter from José Núñez de Cáceres to the governor of Puerto Rico, Santo Domingo, Janury 22, 1811. El documento se halla en muy mal estado de conservación.

- ^ García, José Gabriel (1893) Compendio Dr la Historia de Santo Domingo. Santo Domingo, Editoria de Santo Domingo pp. 36-37

- Cassá, Roberto (1983). Historia social y economia de la República Dominicana. Santo Doming, Punta y Aparte pp. 211-212

- Sáez, José Luis (1994). La Iglesia y el negro esclavo en Santo Domingo: Una historia de tres siglos. Santo Domingo, Patronato de la ciudad colonial de Santo Domingo, p. 162

This Dominican Republic-related article is a stub. You can help Misplaced Pages by expanding it. |