This is the current revision of this page, as edited by Jdenea (talk | contribs) at 08:47, 6 January 2025 (Fixed grammar for clarity). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this version.

Revision as of 08:47, 6 January 2025 by Jdenea (talk | contribs) (Fixed grammar for clarity)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) Appliance for cold food storage "Fridge" redirects here. For other uses, see Fridge (disambiguation) and Refrigerator (disambiguation).

Exterior of a modern refrigerator Exterior of a modern refrigerator | |

| Type | Appliance |

|---|---|

| Inception | 1913; 112 years ago (1913) |

| Manufacturer | Various |

| Available | Globally |

A refrigerator, commonly shortened to fridge, is a commercial and home appliance consisting of a thermally insulated compartment and a heat pump (mechanical, electronic or chemical) that transfers heat from its inside to its external environment so that its inside is cooled to a temperature below the room temperature. Refrigeration is an essential food storage technique around the world. The low temperature reduces the reproduction rate of bacteria, so the refrigerator lowers the rate of spoilage. A refrigerator maintains a temperature a few degrees above the freezing point of water. The optimal temperature range for perishable food storage is 3 to 5 °C (37 to 41 °F). A freezer is a specialized refrigerator, or portion of a refrigerator, that maintains its contents’ temperature below the freezing point of water. The refrigerator replaced the icebox, which had been a common household appliance for almost a century and a half. The United States Food and Drug Administration recommends that the refrigerator be kept at or below 4 °C (40 °F) and that the freezer be regulated at −18 °C (0 °F).

The first cooling systems for food involved ice. Artificial refrigeration began in the mid-1750s, and developed in the early 1800s. In 1834, the first working vapor-compression refrigeration system, using the same technology seen in air conditioners, was built. The first commercial ice-making machine was invented in 1854. In 1913, refrigerators for home use were invented. In 1923 Frigidaire introduced the first self-contained unit. The introduction of Freon in the 1920s expanded the refrigerator market during the 1930s. Home freezers as separate compartments (larger than necessary just for ice cubes) were introduced in 1940. Frozen foods, previously a luxury item, became commonplace.

Freezer units are used in households as well as in industry and commerce. Commercial refrigerator and freezer units were in use for almost 40 years prior to the common home models. The freezer-over-refrigerator style had been the basic style since the 1940s, until modern, side-by-side refrigerators broke the trend. A vapor compression cycle is used in most household refrigerators, refrigerator–freezers and freezers. Newer refrigerators may include automatic defrosting, chilled water, and ice from a dispenser in the door.

Domestic refrigerators and freezers for food storage are made in a range of sizes. Among the smallest are Peltier-type refrigerators designed to chill beverages. A large domestic refrigerator stands as tall as a person and may be about one metre (3 ft 3 in) wide with a capacity of 0.6 m (21 cu ft). Refrigerators and freezers may be free standing, or built into a kitchen. The refrigerator allows the modern household to keep food fresh for longer than before. Freezers allow people to buy perishable food in bulk and eat it at leisure, and make bulk purchases.

History

Technology development

See also: Refrigeration and Low-temperature technology timelineAncient origins

Main article: YakhchālAncient Iranians were among the first to invent a form of cooler utilizing the principles of evaporative cooling and radiative cooling called yakhchāls. These complexes used subterranean storage spaces, a large thickly insulated above-ground domed structure, and outfitted with badgirs (wind-catchers) and series of qanats (aqueducts).

Pre-electric refrigeration

In modern times, before the invention of the modern electric refrigerator, icehouses and iceboxes were used to provide cool storage for most of the year. Placed near freshwater lakes or packed with snow and ice during the winter, they were once very common. Natural means are still used to cool foods today. On mountainsides, runoff from melting snow is a convenient way to cool drinks, and during the winter one can keep milk fresh much longer just by keeping it outdoors. The word "refrigeratory" was used at least as early as the 17th century.

Artificial refrigeration

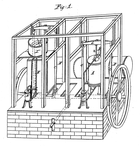

Schematic of Dr. John Gorrie's 1841 mechanical ice machine

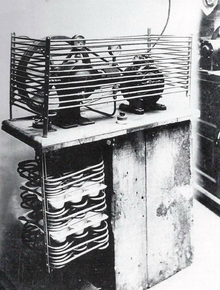

Schematic of Dr. John Gorrie's 1841 mechanical ice machine Ferdinand Carré's ice-making device

Ferdinand Carré's ice-making device

The history of artificial refrigeration began when Scottish professor William Cullen designed a small refrigerating machine in 1755. Cullen used a pump to create a partial vacuum over a container of diethyl ether, which then boiled, absorbing heat from the surrounding air. The experiment even created a small amount of ice, but had no practical application at that time.

In 1805, American inventor Oliver Evans described a closed vapor-compression refrigeration cycle for the production of ice by ether under vacuum. In 1820, the British scientist Michael Faraday liquefied ammonia and other gases by using high pressures and low temperatures, and in 1834, an American expatriate in Great Britain, Jacob Perkins, built the first working vapor-compression refrigeration system. It was a closed-cycle device that could operate continuously. A similar attempt was made in 1842, by American physician, John Gorrie, who built a working prototype, but it was a commercial failure. American engineer Alexander Twining took out a British patent in 1850 for a vapor compression system that used ether.

The first practical vapor compression refrigeration system was built by James Harrison, a Scottish Australian. His 1856 patent was for a vapor compression system using ether, alcohol or ammonia. He built a mechanical ice-making machine in 1851 on the banks of the Barwon River at Rocky Point in Geelong, Victoria, and his first commercial ice-making machine followed in 1854. Harrison also introduced commercial vapor-compression refrigeration to breweries and meat packing houses, and by 1861, a dozen of his systems were in operation.

The first gas absorption refrigeration system (compressor-less and powered by a heat-source) was developed by Edward Toussaint of France in 1859 and patented in 1860. It used gaseous ammonia dissolved in water ("aqua ammonia").

Carl von Linde, an engineering professor at the Technological University Munich in Germany, patented an improved method of liquefying gases in 1876, creating the first reliable and efficient compressed-ammonia refrigerator. His new process made possible the use of gases such as ammonia (NH3), sulfur dioxide (SO2) and methyl chloride (CH3Cl) as refrigerants, which were widely used for that purpose until the late 1920s despite safety concerns. In 1895 he discovered the refrigeration cycle.

Electric refrigerators

In 1894, Hungarian inventor and industrialist István Röck started to manufacture a large industrial ammonia refrigerator which was powered by electric compressors (together with the Esslingen Machine Works). Its electric compressors were manufactured by the Ganz Works. At the 1896 Millennium Exhibition, Röck and the Esslingen Machine Works presented a 6-tonne capacity artificial ice producing plant. In 1906, the first large Hungarian cold store (with a capacity of 3,000 tonnes, the largest in Europe) opened in Tóth Kálmán Street, Budapest, the machine was manufactured by the Ganz Works. Until nationalisation after the Second World War, large-scale industrial refrigerator production in Hungary was in the hands of Röck and Ganz Works.

Commercial refrigerator and freezer units, which go by many other names, were in use for almost 40 years prior to the common home models. They used gas systems such as ammonia (R-717) or sulfur dioxide (R-764), which occasionally leaked, making them unsafe for home use. Practical household refrigerators were introduced in 1915 and gained wider acceptance in the United States in the 1930s as prices fell and non-toxic, non-flammable synthetic refrigerants such as Freon-12 (R-12) were introduced. However, R-12 proved to be damaging to the ozone layer, causing governments to issue a ban on its use in new refrigerators and air-conditioning systems in 1994. The less harmful replacement for R-12, R-134a (tetrafluoroethane), has been in common use since 1990, but R-12 is still found in many old systems.

Refrigeration, continually operated, typically consumes up to 50% of the energy used by a supermarket. Doors, made of glass to allow inspection of contents, improve efficiency significantly over open display cases, which use 1.3 times the energy.

Residential refrigerators

In 1913, the first electric refrigerators for home and domestic use were invented and produced by Fred W. Wolf of Fort Wayne, Indiana, with models consisting of a unit that was mounted on top of an ice box. His first device, produced over the next few years in several hundred units, was called DOMELRE. In 1914, engineer Nathaniel B. Wales of Detroit, Michigan, introduced an idea for a practical electric refrigeration unit, which later became the basis for the Kelvinator. A self-contained refrigerator, with a compressor on the bottom of the cabinet was invented by Alfred Mellowes in 1916. Mellowes produced this refrigerator commercially but was bought out by William C. Durant in 1918, who started the Frigidaire company to mass-produce refrigerators. In 1918, Kelvinator company introduced the first refrigerator with any type of automatic control. The absorption refrigerator was invented by Baltzar von Platen and Carl Munters from Sweden in 1922, while they were still students at the Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm. It became a worldwide success and was commercialized by Electrolux. Other pioneers included Charles Tellier, David Boyle, and Raoul Pictet. Carl von Linde was the first to patent and make a practical and compact refrigerator.

These home units usually required the installation of the mechanical parts, motor and compressor, in the basement or an adjacent room while the cold box was located in the kitchen. There was a 1922 model that consisted of a wooden cold box, water-cooled compressor, an ice cube tray and a 0.25-cubic-metre (9 cu ft) compartment, and cost $714. (A 1922 Model-T Ford cost about $476.) By 1923, Kelvinator held 80 percent of the market for electric refrigerators. Also in 1923 Frigidaire introduced the first self-contained unit. About this same time porcelain-covered metal cabinets began to appear. Ice cube trays were introduced more and more during the 1920s; up to this time freezing was not an auxiliary function of the modern refrigerator.

The first refrigerator to see widespread use was the General Electric "Monitor-Top" refrigerator introduced in 1927, so-called, by the public, because of its resemblance to the gun turret on the ironclad warship USS Monitor of the 1860s. The compressor assembly, which emitted a great deal of heat, was placed above the cabinet, and enclosed by a decorative ring. Over a million units were produced. As the refrigerating medium, these refrigerators used either sulfur dioxide, which is corrosive to the eyes and may cause loss of vision, painful skin burns and lesions, or methyl formate, which is highly flammable, harmful to the eyes, and toxic if inhaled or ingested.

The introduction of Freon in the 1920s expanded the refrigerator market during the 1930s and provided a safer, low-toxicity alternative to previously used refrigerants. Separate freezers became common during the 1940s; the term for the unit, popular at the time, was deep freeze. These devices, or appliances, did not go into mass production for use in the home until after World War II. The 1950s and 1960s saw technical advances like automatic defrosting and automatic ice making. More efficient refrigerators were developed in the 1970s and 1980s, even though environmental issues led to the banning of very effective (Freon) refrigerants. Early refrigerator models (from 1916) had a cold compartment for ice cube trays. From the late 1920s fresh vegetables were successfully processed through freezing by the Postum Company (the forerunner of General Foods), which had acquired the technology when it bought the rights to Clarence Birdseye's successful fresh freezing methods.

Styles of refrigerators

The majority of refrigerators were white in the early 1950s, but between the mid-1950s and the present, manufacturers and designers have added color. Pastel colors, such as pink and turquoise, gained popularity in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Certain versions also had brushed chrome plating, which is akin to a stainless steel appearance. During the latter part of the 1960s and the early 1970s, earth tone colors were popular, including Harvest Gold, Avocado Green and almond. In the 1980s, black became fashionable. In the late 1990s stainless steel came into vogue. Since 1961 the Color Marketing Group has attempted to coordinate the colors of appliances and other consumer goods.

Freezer

"Freezer" redirects here. For other uses, see Freezer (disambiguation).Freezer units are used in households and in industry and commerce. Food stored at or below −18 °C (0 °F) is safe indefinitely. Most household freezers maintain temperatures from −23 to −18 °C (−9 to 0 °F), although some freezer-only units can achieve −34 °C (−29 °F) and lower. Refrigerator freezers generally do not achieve lower than −23 °C (−9 °F), since the same coolant loop serves both compartments: Lowering the freezer compartment temperature excessively causes difficulties in maintaining above-freezing temperature in the refrigerator compartment. Domestic freezers can be included as a separate compartment in a refrigerator, or can be a separate appliance. Domestic freezers may be either upright, resembling a refrigerator, or chest freezers, wider than tall with the lid or door on top, sacrificing convenience for efficiency and partial immunity to power outages. Many modern upright freezers come with an ice dispenser built into their door. Some upscale models include thermostat displays and controls.

Home freezers as separate compartments (larger than necessary just for ice cubes), or as separate units, were introduced in the United States in 1940. Frozen foods, previously a luxury item, became commonplace.

In 1955 the domestic deep freezer, which was cold enough to allow the owners to freeze fresh food themselves rather than buying food already frozen with Clarence Birdseye's process, went on sale.

Walk-in freezer

There are walk in freezers, as the name implies, they allow for one to walk into the freezer. Safety regulations requires an emergency releases and employers should check to ensure no one will trapped inside when the unit gets locked as hypothermia is possible if one is in freezer for longer periods of time.

Refrigerator technologies

See also: Heat pump and refrigeration cycle

Compressor refrigerators

A vapor compression cycle is used in most household refrigerators, refrigerator–freezers and freezers. In this cycle, a circulating refrigerant such as R134a enters a compressor as low-pressure vapor at or slightly below the temperature of the refrigerator interior. The vapor is compressed and exits the compressor as high-pressure superheated vapor. The superheated vapor travels under pressure through coils or tubes that make up the condenser; the coils or tubes are passively cooled by exposure to air in the room. The condenser cools the vapor, which liquefies. As the refrigerant leaves the condenser, it is still under pressure but is now only slightly above room temperature. This liquid refrigerant is forced through a metering or throttling device, also known as an expansion valve (essentially a pin-hole sized constriction in the tubing) to an area of much lower pressure. The sudden decrease in pressure results in explosive-like flash evaporation of a portion (typically about half) of the liquid. The latent heat absorbed by this flash evaporation is drawn mostly from adjacent still-liquid refrigerant, a phenomenon known as auto-refrigeration. This cold and partially vaporized refrigerant continues through the coils or tubes of the evaporator unit. A fan blows air from the compartment ("box air") across these coils or tubes and the refrigerant completely vaporizes, drawing further latent heat from the box air. This cooled air is returned to the refrigerator or freezer compartment, and so keeps the box air cold. Note that the cool air in the refrigerator or freezer is still warmer than the refrigerant in the evaporator. Refrigerant leaves the evaporator, now fully vaporized and slightly heated, and returns to the compressor inlet to continue the cycle.

Modern domestic refrigerators are extremely reliable because motor and compressor are integrated within a welded container, "sealed unit", with greatly reduced likelihood of leakage or contamination. By comparison, externally-coupled refrigeration compressors, such as those in automobile air conditioning, inevitably leak fluid and lubricant past the shaft seals. This leads to a requirement for periodic recharging and, if ignored, possible compressor failure.

Dual compartment designs

Refrigerators with two compartments need special design to control the cooling of refrigerator or freezer compartments. Typically, the compressors and condenser coils are mounted at the top of the cabinet, with a single fan to cool them both. This arrangement has a few downsides: each compartment cannot be controlled independently and the more humid refrigerator air is mixed with the dry freezer air.

Multiple manufacturers offer dual compressor models. These models have separate freezer and refrigerator compartments that operate independently of each other, sometimes mounted within a single cabinet. Each has its own separate compressor, condenser and evaporator coils, insulation, thermostat, and door.

A hybrid between the two designs is using a separate fan for each compartment, the Dual Fan approach. Doing so allows for separate control and airflow on a single compressor system.

Absorption refrigerators

An absorption refrigerator works differently from a compressor refrigerator, using a source of heat, such as combustion of liquefied petroleum gas, solar thermal energy or an electric heating element. These heat sources are much quieter than the compressor motor in a typical refrigerator. A fan or pump might be the only mechanical moving parts; reliance on convection is considered impractical.

Other uses of an absorption refrigerator (or "chiller") include large systems used in office buildings or complexes such as hospitals and universities. These large systems are used to chill a brine solution that is circulated through the building.

Peltier effect refrigerators

The Peltier effect uses electricity to pump heat directly; refrigerators employing this system are sometimes used for camping, or in situations where noise is not acceptable. They can be totally silent (if a fan for air circulation is not fitted) but are less energy-efficient than other methods.

Ultra-low temperature refrigerators

"Ultra-cold" or "ultra-low temperature (ULT)" (typically −80 or −86 °C ) freezers, as used for storing biological samples, also generally employ two stages of cooling, but in cascade. The lower temperature stage uses methane, or a similar gas, as a refrigerant, with its condenser kept at around −40 °C by a second stage which uses a more conventional refrigerant.

For much lower temperatures, laboratories usually purchase liquid nitrogen (−196 °C ), kept in a Dewar flask, into which the samples are suspended. Cryogenic chest freezers can achieve temperatures of down to −150 °C (−238 °F), and may include a liquid nitrogen backup.

Other refrigerators

Alternatives to the vapor-compression cycle not in current mass production include:

- Acoustic cooling

- Air cycle

- Magnetic cooling

- Malone engine

- Pulse tube

- Stirling cycle

- Thermoelectric cooling

- Thermionic cooling

- Vortex tube

- Water cycle systems.

Layout

| This article or section appears to contradict itself on which compartment controls temperature. Please see the talk page for more information. (May 2024) |

Many modern refrigerator/freezers have the freezer on top and the refrigerator on the bottom. Most refrigerator-freezers—except for manual defrost models or cheaper units—use what appears to be two thermostats. Only the refrigerator compartment is properly temperature controlled. When the refrigerator gets too warm, the thermostat starts the cooling process and a fan circulates the air around the freezer. During this time, the refrigerator also gets colder. The freezer control knob only controls the amount of air that flows into the refrigerator via a damper system. Changing the refrigerator temperature will inadvertently change the freezer temperature in the opposite direction. Changing the freezer temperature will have no effect on the refrigerator temperature. The freezer control may also be adjusted to compensate for any refrigerator adjustment.

This means the refrigerator may become too warm. However, because only enough air is diverted to the refrigerator compartment, the freezer usually re-acquires the set temperature quickly, unless the door is opened. When a door is opened, either in the refrigerator or the freezer, the fan in some units stops immediately to prevent excessive frost build up on the freezer's evaporator coil, because this coil is cooling two areas. When the freezer reaches temperature, the unit cycles off, no matter what the refrigerator temperature is. Modern computerized refrigerators do not use the damper system. The computer manages fan speed for both compartments, although air is still blown from the freezer.

Features

Newer refrigerators may include:

- Automatic defrosting

- A power failure warning that alerts the user by flashing a temperature display. It may display the maximum temperature reached during the power failure, and whether frozen food has defrosted or may contain harmful bacteria.

- Chilled water and ice from a dispenser in the door. Water and ice dispensing became available in the 1970s. In some refrigerators, the process of making ice is built-in so the user doesn't have to manually use ice trays. Some refrigerators have water chillers and water filtration systems.

- Cabinet rollers that lets the refrigerator roll out for easier cleaning

- Adjustable shelves and trays

- A status indicator that notifies when it is time to change the water filter

- An in-door ice caddy, which relocates the ice-maker storage to the freezer door and saves approximately 60 litres (2.1 cu ft) of usable freezer space. It is also removable, and helps to prevent ice-maker clogging.

- A cooling zone in the refrigerator door shelves. Air from the freezer section is diverted to the refrigerator door, to cool milk or juice stored in the door shelf.

- A drop down door built into the refrigerator main door, giving easy access to frequently used items such as milk, thus saving energy by not having to open the main door.

- A Fast Freeze function to rapidly cool foods by running the compressor for a predetermined amount of time and thus temporarily lowering the freezer temperature below normal operating levels. It is recommended to use this feature several hours before adding more than 1 kg of unfrozen food to the freezer. For freezers without this feature, lowering the temperature setting to the coldest will have the same effect.

- Freezer Defrost: Early freezer units accumulated ice crystals around the freezing units. This was a result of humidity introduced into the units when the doors to the freezer were opened condensing on the cold parts, then freezing. This frost buildup required periodic thawing ("defrosting") of the units to maintain their efficiency. Manual Defrost (referred to as Cyclic) units are still available. Advances in automatic defrosting eliminating the thawing task were introduced in the 1950s, but are not universal, due to energy performance and cost. These units used a counter that only defrosted the freezer compartment (Freezer Chest) when a specific number of door openings had been made. The units were just a small timer combined with an electrical heater wire that heated the freezer's walls for a short amount of time to remove all traces of frost/frosting. Also, early units featured freezer compartments located within the larger refrigerator, and accessed by opening the refrigerator door, and then the smaller internal freezer door; units featuring an entirely separate freezer compartment were introduced in the early 1960s, becoming the industry standard by the middle of that decade.

These older freezer compartments were the main cooling body of the refrigerator, and only maintained a temperature of around −6 °C (21 °F), which is suitable for keeping food for a week.

- Butter heater: In the early 1950s, the butter conditioner's patent was filed and published by the inventor Nave Alfred E. This feature was supposed to "provide a new and improved food storage receptacle for storing butter or the like which may quickly and easily be removed from the refrigerator cabinet for the purpose of cleaning." Because of the high interest to the invention, companies in UK, New Zealand, and Australia started to include the feature into the mass refrigerator production and soon it became a symbol of the local culture. However, not long after that it was removed from production as according to the companies this was the only way for them to meet new ecology regulations and they found it inefficient to have a heat generating device inside a refrigerator.

Later advances included automatic ice units and self compartmentalized freezing units.

Types of domestic refrigerators

Domestic refrigerators and freezers for food storage are made in a range of sizes. Among the smallest is a 4-litre (0.14 cu ft) Peltier refrigerator advertised as being able to hold 6 cans of beer. A large domestic refrigerator stands as tall as a person and may be about 1 metre (3.3 ft) wide with a capacity of 600 litres (21 cu ft). Some models for small households fit under kitchen work surfaces, usually about 86 centimetres (34 in) high. Refrigerators may be combined with freezers, either stacked with refrigerator or freezer above, below, or side by side. A refrigerator without a frozen food storage compartment may have a small section just to make ice cubes. Freezers may have drawers to store food in, or they may have no divisions (chest freezers).

Refrigerators and freezers may be free-standing, or built into a kitchen's cabinet.

Three distinct classes of refrigerator are common:

Compressor refrigerators

- Compressor refrigerators are by far the most common type; they make a noticeable noise, but are most efficient and give greatest cooling effect. Portable compressor refrigerators for recreational vehicle (RV) and camping use are expensive but effective and reliable. Refrigeration units for commercial and industrial applications can be made in various sizes, shapes and styles to fit customer needs. Commercial and industrial refrigerators may have their compressors located away from the cabinet (similar to split system air conditioners) to reduce noise nuisance and reduce the load on air conditioning in hot weather.

Absorption refrigerator

- Absorption refrigerators may be used in caravans and trailers, and dwellings lacking electricity, such as farms or rural cabins, where they have a long history. They may be powered by any heat source: gas (natural or propane) or kerosene being common. Models made for camping and RV use often have the option of running (inefficiently) on 12 volt battery power.

Peltier refrigerators

- Peltier refrigerators are powered by electricity, usually 12 volt DC, but mains-powered wine coolers are available. Peltier refrigerators are inexpensive but inefficient and become progressively more inefficient with increased cooling effect; much of this inefficiency may be related to the temperature differential across the short distance between the "hot" and "cold" sides of the Peltier cell. Peltier refrigerators generally use heat sinks and fans to lower this differential; the only noise produced comes from the fan. Reversing the polarity of the voltage applied to the Peltier cells results in a heating rather than cooling effect.

Other specialized cooling mechanisms may be used for cooling, but have not been applied to domestic or commercial refrigerators.

Magnetic refrigerator

- Magnetic refrigerators are refrigerators that work on the magnetocaloric effect. The cooling effect is triggered by placing a metal alloy in a magnetic field.

- Acoustic refrigerators are refrigerators that use resonant linear reciprocating motors/alternators to generate a sound that is converted to heat and cold using compressed helium gas. The heat is discarded and the cold is routed to the refrigerator.

Energy efficiency

In a house without air-conditioning (space heating and/or cooling) refrigerators consume more energy than any other home device. In the early 1990s a competition was held among the major US manufacturers to encourage energy efficiency. Current US models that are Energy Star qualified use 50% less energy than the average 1974 model used. The most energy-efficient unit made in the US consumes about half a kilowatt-hour per day (equivalent to 20 W continuously). But even ordinary units are reasonably efficient; some smaller units use less than 0.2 kWh per day (equivalent to 8 W continuously). Larger units, especially those with large freezers and icemakers, may use as much as 4 kW·h per day (equivalent to 170 W continuously). The European Union uses a letter-based mandatory energy efficiency rating label, with A being the most efficient, instead of the Energy Star.

For US refrigerators, the Consortium on Energy Efficiency (CEE) further differentiates between Energy Star qualified refrigerators. Tier 1 refrigerators are those that are 20% to 24.9% more efficient than the Federal minimum standards set by the National Appliance Energy Conservation Act (NAECA). Tier 2 are those that are 25% to 29.9% more efficient. Tier 3 is the highest qualification, for those refrigerators that are at least 30% more efficient than Federal standards. About 82% of the Energy Star qualified refrigerators are Tier 1, with 13% qualifying as Tier 2, and just 5% at Tier 3.

Besides the standard style of compressor refrigeration used in ordinary household refrigerators and freezers, there are technologies such as absorption and magnetic refrigeration. Although these designs generally use a much more energy than compressor refrigeration, other qualities such as silent operation or the ability to use gas can favor their use in small enclosures, a mobile environment or in environments where failure of refrigeration must not be possible.

Many refrigerators made in the 1930s and 1940s were far more efficient than most that were made later. This is partly due to features added later, such as auto-defrost, that reduced efficiency. Additionally, after World War 2, refrigerator style became more important than efficiency. This was especially true in the US in the 1970s, when side-by-side models (known as American fridge-freezers outside of the US) with ice dispensers and water chillers became popular. The amount of insulation used was also often decreased to reduce refrigerator case size and manufacturing costs.

Improvement

Over time standards of refrigerator energy efficiency have been introduced and tightened, which has driven steady improvement; 21st-century refrigerators are typically three times more energy-efficient than in the 1930s.

The efficiency of older refrigerators can be improved by regular defrosting (if the unit is manual defrost) and cleaning, replacing deteriorated door seals with new ones, not setting the thermostat colder than actually required (a refrigerator does not usually need to be colder than 4 °C (39 °F)), and replacing insulation, where applicable. Cleaning condenser coils to remove dust impeding heat flow, and ensuring that there is space for air flow around the condenser can improve efficiency.

Auto defrosting

Main article: Auto-defrostFrost-free refrigerators and freezers use electric fans to cool the appropriate compartment. This could be called a "fan forced" refrigerator, whereas manual defrost units rely on colder air lying at the bottom, versus the warm air at the top to achieve adequate cooling. The air is drawn in through an inlet duct and passed through the evaporator where it is cooled, the air is then circulated throughout the cabinet via a series of ducts and vents. Because the air passing the evaporator is supposedly warm and moist, frost begins to form on the evaporator (especially on a freezer's evaporator). In cheaper and/or older models, a defrost cycle is controlled via a mechanical timer. This timer is set to shut off the compressor and fan and energize a heating element located near or around the evaporator for about 15 to 30 minutes at every 6 to 12 hours. This melts any frost or ice build-up and allows the refrigerator to work normally once more. It is believed that frost free units have a lower tolerance for frost, due to their air-conditioner-like evaporator coils. Therefore, if a door is left open accidentally (especially the freezer), the defrost system may not remove all frost, in this case, the freezer (or refrigerator) must be defrosted.

If the defrosting system melts all the ice before the timed defrosting period ends, then a small device (called a defrost limiter) acts like a thermostat and shuts off the heating element to prevent too large a temperature fluctuation, it also prevents hot blasts of air when the system starts again, should it finish defrosting early. On some early frost-free models, the defrost limiter also sends a signal to the defrost timer to start the compressor and fan as soon as it shuts off the heating element before the timed defrost cycle ends. When the defrost cycle is completed, the compressor and fan are allowed to cycle back on.

Frost-free refrigerators, including some early frost-free refrigerators/freezers that used a cold plate in their refrigerator section instead of airflow from the freezer section, generally don't shut off their refrigerator fans during defrosting. This allows consumers to leave food in the main refrigerator compartment uncovered, and also helps keep vegetables moist. This method also helps reduce energy consumption, because the refrigerator is above freeze point and can pass the warmer-than-freezing air through the evaporator or cold plate to aid the defrosting cycle.

Inverter

With the advent of digital inverter compressors, the energy consumption is even further reduced than a single-speed induction motor compressor, and thus contributes far less in the way of greenhouse gases.

The energy consumption of a refrigerator is also dependent on the type of refrigeration being done. For instance, Inverter Refrigerators consume comparatively less energy than a typical non-inverter refrigerator. In an inverter refrigerator, the compressor is used conditionally on requirement basis. For instance, an inverter refrigerator might use less energy during the winters than it does during the summers. This is because the compressor works for a shorter time than it does during the summers.

Further, newer models of inverter compressor refrigerators take into account various external and internal conditions to adjust the compressor speed and thus optimize cooling and energy consumption. Most of them use at least 4 sensors which help detect variance in external temperature, internal temperature owing to opening of the refrigerator door or keeping new food inside; humidity and usage patterns. Depending on the sensor inputs, the compressor adjusts its speed. For example, if door is opened or new food is kept, the sensor detects an increase in temperature inside the cabin and signals the compressor to increase its speed till a pre-determined temperature is attained. After which, the compressor runs at a minimum speed to just maintain the internal temperature. The compressor typically runs between 1200 and 4500 rpm. Inverter compressors not only optimizes cooling but is also superior in terms of durability and energy efficiency. A device consumes maximum energy and undergoes maximum wear and tear when it switches itself on. As an inverter compressor never switches itself off and instead runs on varying speed, it minimizes wear and tear and energy usage. LG played a significant role in improving inverter compressors as we know it by reducing the friction points in the compressor and thus introducing Linear Inverter Compressors. Conventionally, all domestic refrigerators use a reciprocating drive which is connected to the piston. But in a linear inverter compressor, the piston which is a permanent magnet is suspended between two electromagnets. The AC changes the magnetic poles of the electromagnet, which results in the push and pull that compresses the refrigerant. LG claims that this helps reduce energy consumption by 32% and noise by 25% compared to their conventional compressors.

Form factor

The physical design of refrigerators also plays a large part in its energy efficiency. The most efficient is the chest-style freezer, as its top-opening design minimizes convection when opening the doors, reducing the amount of warm moist air entering the freezer. On the other hand, in-door ice dispensers cause more heat leakage, contributing to an increase in energy consumption.

Impact

Global adoption

The gradual global adoption of refrigerators marks a transformative era in food preservation and domestic convenience. Since the refrigerators introduction in the 20th century, refrigerators have transitioned from being luxurious items to everyday commodities which have altered the understandings of food storage practices. Refrigerators have significantly impacted various aspects of many individual's daily lives by providing food safety to people around the world spanning across a wide variety of cultural and socioeconomic backgrounds.

The global adoption of refrigerators has also changed how societies handle their food supply. The introduction of the refrigerator in different societies has resulted in the monetization and industrialized mass food production systems which are commonly linked to increased food waste, animal wastes, and dangerous chemical wastes being traced back into different ecosystems. In addition, refrigerators have also provided an easier way to access food for many individuals around the world, with many options that commercialization has promoted leaning towards low-nutrient dense foods.

After consumer refrigerators became financially viable for production and sale on a large scale, their prevalence around the globe expanded greatly. In the United States, an estimated 99.5% of households have a refrigerator. Refrigerator ownership is more common in developed Western countries, but has stayed relatively low in Eastern and developing countries despite its growing popularity. Throughout Eastern Europe and the Middle East, only 80% of the population own refrigerators. In addition to this, 65% of the population in China are stated to have refrigerators. The distribution of consumer refrigerators is also skewed as urban areas exhibit larger refrigeration ownership percentages compared to rural areas.

Supplantation of the ice trade

The ice trade was an industry in the 19th and 20th centuries of the harvesting, transportation, and sale of natural and artificial ice for the purposes of refrigeration and consumption. The majority of the ice used for trade was harvested from North America and transported globally with some smaller operations working out of Norway. With the introduction of more affordable large and home scale refrigeration around the 1920s, the need for large scale ice harvest and transportation was no longer needed, and the ice trade subsequently slowed and shrank to smaller scale local services or disappeared altogether.

Effect on diet and lifestyle

The refrigerator allows households to keep food fresh for longer than before. The most notable improvement is for meat and other highly perishable wares, which previously needed to be preserved or otherwise processed for long-term storage and transport. This change in the supply chains of food products led to a marked increase in the quality of food in areas where refrigeration was being used. Additionally, the increased freshness and shelf life of food caused by the advent of refrigeration in addition to growing global communication methods has resulted in an increase in cultural exchange through food products from different regions of the world. There have also been claims that this increase in the quality of food is responsible for an increase in the height of United States citizens around the early 1900s.

Refrigeration has also contributed to a decrease in the quality of food in some regions. By allowing, in part, for the phenomenon of globalization in the food sector, refrigeration has made the creation and transportation of ultra-processed foods and convenience foods inexpensive, leading to their prevalence, especially in lower-income regions. These regions of lessened access to higher quality foods are referred to as food deserts.

Freezers allow people to buy food in bulk and eat it at leisure, and bulk purchases may save money. Ice cream, a popular commodity of the 20th century, could previously only be obtained by traveling to where the product was made and eating it on the spot. Now it is a common food item. Ice on demand not only adds to the enjoyment of cold drinks, but is useful for first-aid, and for cold packs that can be kept frozen for picnics or in case of emergency.

Temperature zones and ratings

Residential units

The capacity of a refrigerator is measured in either liters or cubic feet. Typically the volume of a combined refrigerator-freezer is split with 1/3 to 1/4 of the volume allocated to the freezer although these values are highly variable.

Temperature settings for refrigerator and freezer compartments are often given arbitrary numbers by manufacturers (for example, 1 through 9, warmest to coldest), but generally 3 to 5 °C (37 to 41 °F) is ideal for the refrigerator compartment and −18 °C (0 °F) for the freezer. Some refrigerators must be within certain external temperature parameters to run properly. This can be an issue when placing units in an unfinished area, such as a garage.

Some refrigerators are now divided into four zones to store different types of food:

- −18 °C (0 °F) (freezer)

- 0 °C (32 °F) (meat zone)

- 5 °C (41 °F) (cooling zone)

- 10 °C (50 °F) (crisper)

European freezers, and refrigerators with a freezer compartment, have a four-star rating system to grade freezers.

| min temperature: −6 °C (21 °F). Maximum storage time for (pre-frozen) food is 1 week | |

| min temperature: −12 °C (10 °F). Maximum storage time for (pre-frozen) food is 1 month | |

| min temperature: −18 °C (0 °F). Maximum storage time for (pre-frozen) food is between 3 and 12 months depending on type (meat, vegetables, fish, etc.) | |

| min temperature: −18 °C (0 °F). Maximum storage time for pre-frozen or frozen-from-fresh food is between 3 and 12 months |

Although both the three- and four-star ratings specify the same storage times and same minimum temperature of −18 °C (0 °F), only a four-star freezer is intended for freezing fresh food, and may include a "fast freeze" function (runs the compressor continually, down to as low as −26 °C (−15 °F)) to facilitate this. Three (or fewer) stars are used for frozen food compartments that are only suitable for storing frozen food; introducing fresh food into such a compartment is likely to result in unacceptable temperature rises. This difference in categorization is shown in the design of the 4-star logo, where the "standard" three stars are displayed in a box using "positive" colours, denoting the same normal operation as a 3-star freezer, and the fourth star showing the additional fresh food/fast freeze function is prefixed to the box in "negative" colours or with other distinct formatting.

Most European refrigerators include a moist cold refrigerator section (which does require (automatic) defrosting at irregular intervals) and a (rarely frost-free) freezer section.

Commercial refrigeration temperatures

(from warmest to coolest)

- Refrigerators

- 2 to 3 °C (35 to 38 °F), and not greater than maximum refrigerator temperature at 5 °C (41 °F)

- Freezer, Reach-in

- −23 to −15 °C (−10 to +5 °F)

- Freezer, Walk-in

- −23 to −18 °C (−10 to 0 °F)

- Freezer, Ice Cream

- −29 to −23 °C (−20 to −10 °F)

Cryogenics

- Cryocooler: below -153 °C (-243.4 °F)

- Dilution refrigerator: down to -273.148 °C (-459.6664 °F)

Disposal

An increasingly important environmental concern is the disposal of old refrigerators—initially because freon coolant damages the ozone layer—but as older generation refrigerators wear out, the destruction of CFC-bearing insulation also causes concern. Modern refrigerators usually use a refrigerant called HFC-134a (1,1,1,2-Tetrafluoroethane), which does not deplete the ozone layer, unlike Freon. R-134a is becoming much rarer in Europe, where newer refrigerants are being used instead. The main refrigerant now used is R-600a (also known as isobutane), which has a smaller effect on the atmosphere if released. There have been reports of refrigerators exploding if the refrigerant leaks isobutane in the presence of a spark. If the coolant leaks into the refrigerator, at times when the door is not being opened (such as overnight) the concentration of coolant in the air within the refrigerator can build up to form an explosive mixture that can be ignited either by a spark from the thermostat or when the light comes on as the door is opened, resulting in documented cases of serious property damage and injury or even death from the resulting explosion.

Disposal of discarded refrigerators is regulated, often mandating the removal of doors for safety reasons. Children have been asphyxiated while playing with discarded refrigerators, particularly older models with latching doors. Since the 1950s regulations in many places have banned the use of refrigerator doors that cannot be opened by pushing from inside. Modern units use a magnetic door gasket that holds the door sealed but allows it to be pushed open from the inside. This gasket was invented, developed and manufactured by Max Baermann (1903–1984) of Bergisch Gladbach/Germany.

Regarding total life-cycle costs, many governments offer incentives to encourage recycling of old refrigerators. One example is the Phoenix refrigerator program launched in Australia. This government incentive picked up old refrigerators, paying their owners for "donating" the refrigerator. The refrigerator was then refurbished, with new door seals, a thorough cleaning, and the removal of items such as the cover that is strapped to the back of many older units. The resulting refrigerators, now over 10% more efficient, were then given to low-income families. The United States also has a program for collecting and replacing older, less-efficient refrigerators and other white goods. These programs seek to replace large appliances that are old and inefficient or faulty by newer, more energy-efficient appliances, to reduce the cost imposed on lower-income families, and reduce pollution caused by the older appliances.

Gallery

(view as a 360° interactive panorama)

-

McCray pre-electric home refrigerator ad from 1905; this company, founded in 1887, is still in business

McCray pre-electric home refrigerator ad from 1905; this company, founded in 1887, is still in business

-

A 1930s era General Electric "Globe Top" refrigerator in the Ernest Hemingway House

A 1930s era General Electric "Globe Top" refrigerator in the Ernest Hemingway House

-

General Electric "Monitor-Top" refrigerator, still in use, June 2007

General Electric "Monitor-Top" refrigerator, still in use, June 2007

-

Frigidaire Imperial "Frost Proof" model FPI-16BC-63, top refrigerator/bottom freezer with brushed chrome door finish made by General Motors Canada in 1963

Frigidaire Imperial "Frost Proof" model FPI-16BC-63, top refrigerator/bottom freezer with brushed chrome door finish made by General Motors Canada in 1963

-

A side-by-side refrigerator-freezer with an icemaker (2011)

A side-by-side refrigerator-freezer with an icemaker (2011)

See also

- Auto-defrost

- Cold chain

- Continuous freezers

- Einstein refrigerator

- Home automation

- Ice cream maker

- Ice famine

- Smart refrigerator

- Kimchi refrigerator

- Home appliance

- Pot-in-pot refrigerator

- Refrigerator death

- Refrigerator magnet

- Solar-powered refrigerator

- Star rating

- Water dispenser

- Wine cellar

References

- Peavitt, Helen (15 November 2017). Refrigerator: The Story of Cool in the Kitchen. Reaktion Books. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-78023-797-8.

- Aung, Myo Min; Chang, Yoon Seok (11 October 2022). Cold Chain Management. Springer Nature. p. 46. ISBN 978-3-031-09567-2.

- ^ . Keep your fridge-freezer clean and ice-free. BBC. 30 April 2008

- R, Rajesh Kumar (1 August 2020). Basics of Mechanical Engineering. Jyothis Publishers. p. 117. ISBN 978-93-5254-883-5.

- . Are You Storing Food Safely? Archived 5 March 2022 at the Wayback Machine FDA. 9 February 2021

- Accorsi, Riccardo; Manzini, Riccardo (12 June 2019). Sustainable Food Supply Chains: Planning, Design, and Control through Interdisciplinary Methodologies. Academic Press. p. 189. ISBN 978-0-12-813412-2.

- Traitler, Helmut; Dubois, Michel J. F.; Heikes, Keith; Petiard, Vincent; Zilberman, David (5 February 2018). Megatrends in Food and Agriculture: Technology, Water Use and Nutrition. John Wiley & Sons. p. 120. ISBN 978-1-119-39114-2.

- Yahia, Elhadi M. (16 July 2019). Postharvest Technology of Perishable Horticultural Commodities. Woodhead Publishing. p. 212. ISBN 978-0-12-813277-7.

- Zhang, Ce; Yang, Jianming (3 January 2020). A History of Mechanical Engineering. Springer Nature. p. 117. ISBN 978-981-15-0833-2.

- O'Reilly, Catherine (17 November 2008). Did Thomas Crapper Really Invent the Toilet?: The Inventions That Changed Our Homes and Our Lives. Skyhorse Publishing, Inc. ISBN 978-1-62873-278-8.

- Ebrahimi, Ali; Shayegani, Aida; Zarandi, Mahnaz Mahmoudi (2021). "Thermal Performance of Sustainable Element in Moayedi Icehouse in Iran". International Journal of Architectural Heritage. 15 (5): 740–756. doi:10.1080/15583058.2019.1645243. S2CID 202094054. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- Venetum Britannicum, 1676, London, p. 176 in the 1678 edition.

- Arora, Ramesh Chandra (30 March 2012). "Mechanical vapour compression refrigeration". Refrigeration and Air Conditioning. New Delhi, India: PHI Learning. p. 3. ISBN 978-81-203-3915-6.

- Burstall, Aubrey F. (1965). A History of Mechanical Engineering. The MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-52001-X.

- US 8080A, John Gorrie, "Improved process for the artificial production of ice", issued 1851-05-06 Archived 11 March 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- "Step into German - German(y) - The TOP 40 German Inventions - Goethe-Institut". www.goethe.de. Retrieved 19 October 2017.

- "Refrigerator vacuum dehydration unit". Vacuum. 28 (2): 81. February 1978. doi:10.1016/s0042-207x(78)80528-4. ISSN 0042-207X.

- The development and heyday of mechanical science (Hungarian)

- Fricke, Brian; Becker, Bryan (12–15 July 2010). Energy Use of Doored and Open Vertical Refrigerated Display Cases. International Refrigeration and Air Conditioning Conference. Purdue – via Purdue e-Pubs.

- US 1126605, Fred W. Wolf, "Refrigerating apparatus", issued 1915-01-26 Archived 7 March 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- Dennis R. Heldman (29 August 2003). Encyclopedia of Agricultural, Food, and Biological Engineering (Print). CRC Press. p. 350. ISBN 978-0-8247-0938-9. Archived from the original on 5 May 2016.

- "DOMELRE First Electric Refrigerator | ashrae.org". www.ashrae.org. Archived from the original on 2 August 2021. Retrieved 2 August 2021.

- "Air Conditioning and Refrigeration History - part 3 - Greatest Engineering Achievements of the Twentieth Century". www.greatachievements.org. Archived from the original on 2 August 2021. Retrieved 2 August 2021.

- "G.E. Monitor Top Refrigerator". www.industrialdesignhistory.com. Archived from the original on 16 April 2020. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- Lobocki, Neil (4 October 2017). "The General Electric Monitor Top Refrigerator". Archived from the original on 25 January 2020. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- "GE Monitor-Top Refrigerator - Albany Institute of History and Art". www.albanyinstitute.org. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- "The History of Household Wonders: History of the Refrigerator". History.com. A&E Television Networks. 2006. Archived from the original on 26 March 2008.

- "Freezing and food safety". USDA. Archived from the original on 18 September 2013. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- "Advertising". The Australian Women's Weekly. Australia. 19 September 1973. p. 26. Archived from the original on 25 April 2023. Retrieved 13 January 2020 – via Trove.

- Barnes-Svarney, Patricia; Svarney, Thomas E. (23 February 2015). The Handy Nutrition Answer Book. Visible Ink Press. ISBN 9781578595532. Archived from the original on 25 April 2023. Retrieved 14 March 2023.

- "Power To The People – Chicago Tribune". Chicago Tribune. 25 February 1990. Archived from the original on 16 January 2023. Retrieved 16 January 2023.

- "What are The Health and Safety Standards for Walk-in Refrigeration?". 28 March 2024. Retrieved 24 May 2024.

- "What is Dual-Cooling Technology?". www.sears.com. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 13 May 2020.

- James, Stephen J. (2003). "Developments in domestic refrigeration and consumer attitudes" (PDF). Bulletin of the IIR. 5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 March 2009.

- Refrigerator – Adjusting Temperature Controls. geappliances.com

- US 2579848, Alfred E. Nave, "Butter conditioner", issued 1951-12-25 Archived 15 April 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- "Towards the magnetic fridge" Archived 7 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Physorg. 21 April 2006

- "Which UK – Saving Energy". Which UK. Archived from the original on 10 November 2014. Retrieved 10 November 2014.

- Feist, J. W.; Farhang, R.; Erickson, J.; Stergakos, E. (1994). "Super Efficient Refrigerators: The Golden Carrot from Concept to Reality" (PDF). Proceedings of the ACEEE. 3: 3.67 – 3.76. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 September 2013.

- "Refrigerators & Freezers". Energy Star. Archived from the original on 7 February 2006.

- Itakura, Kosuke. Sun Frost – The World's Most Efficient Refrigerators. Humboldt.edu

- "High-efficiency specifications for REFRIGERATORS" (PDF). Consortium for Energy Efficiency. January 2007. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 January 2013.

- "Successes of Energy Efficiency: The United States and California National Trust" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 February 2012.

- Calwell, Chris & Reeder, Travis (2001). "Out With the Old, In With the New" (PDF). Natural Resources Defense Council. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 June 2011.

- Kakaç, Sadik; Avelino, M. R.; Smirnov, H. F. (6 December 2012). Low Temperature and Cryogenic Refrigeration. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9789401000994. Archived from the original on 25 April 2023. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- ^ Badri, Deyae; Toublanc, Cyril; Rouaud, Olivier; Havet, Michel (1 November 2021). "Review on frosting, defrosting and frost management techniques in industrial food freezers". Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 151: 111545. Bibcode:2021RSERv.15111545B. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2021.111545. ISSN 1364-0321.

- "How the Digital Inverter Compressor Has Transformed the Modern Refrigerator". news.samsung.com. Archived from the original on 15 February 2020. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- Chang, Wen Ruey; Liu, Der Yeong; Chen, San Guei; and Wu, Nan Yi, "The Components and Control Methods for Implementation of Inverter-Controlled Refrigerators/Freezers" (2004). International Refrigeration and Air Conditioning Conference. Paper 696. http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/iracc/696

- Technology Connections (7 April 2020). "Chest Freezers; What they tell us about designing for X". YouTube. Archived from the original on 12 May 2020. Retrieved 13 May 2020.

- Meuse, Matt (21 April 2023). "How the humble household refrigerator changed the world — for better and for worse".

- "Not just a cool convenience: How electric refrigeration shaped the "cold chain"". americanhistory.si.edu. 5 November 2015. Retrieved 5 December 2023.

- Martinez, Sebastian; Murguia, Juan M.; Rejas, Brisa; Winters, Solis (13 January 2021). "Refrigeration and child growth: What is the connection?". Maternal & Child Nutrition. 17 (2): e13083. doi:10.1111/mcn.13083. ISSN 1740-8695. PMC 7988856. PMID 33439555.

- Clemen, Rudolf A. “The American Ice Harvests: An Historical Study in Technology, 1800–1918. By Richard O. Cummings. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1949. Pp. x, 184. $3.00.” The Journal of economic history 10.2 (1950): 226–227. Web.

- "Tracing the History of New England's Ice Trade". Boston University. 7 February 2022. Retrieved 4 December 2023.

- ^ Craig, L. A. (1 June 2004). "The Effect of Mechanical Refrigeration on Nutrition in the United States". Social Science History. 28 (2): 325–336. doi:10.1215/01455532-28-2-325 (inactive 1 November 2024). ISSN 0145-5532.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - Commission Regulation (EU) 2019/2019 of 1 October 2019 laying down ecodesign requirements for refrigerating appliances pursuant to Directive 2009/125/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council and repealing Commission Regulation (EC) No 643/2009 (Text with EEA relevance.), 5 December 2019, archived from the original on 25 April 2023, retrieved 21 October 2020

- Lobocki, Neil (4 October 2017). "The First Absorption Refrigerator". Archived from the original on 26 January 2020. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- US 95817S, Norman Bel Geddes, "Design for a refrigerator cabinet", issued 1935-06-04 Archived 11 March 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- US 2127212A, Norman Bel Geddes, "Refrigerator", published 1935-07-24, issued 1938-08-16 Archived 13 June 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- "Norman Bel Geddes Database". norman.hrc.utexas.edu. Archived from the original on 26 January 2020. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- "CPSC, Warns That Old Servel Gas Refrigerators Still In Use Can Be Deadly". U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission. 19 May 2016. Archived from the original on 26 January 2020. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- "Tragic bride-to-be's fridge-freezer exploded and 'turned into a Bunsen burner'". Daily Mirror. 12 November 2015. Archived from the original on 5 August 2017. Retrieved 14 June 2017. Daily Mirror November 2015

- PART 1750—STANDARD FOR DEVICES TO PERMIT THE OPENING OF HOUSEHOLD REFRIGERATOR DOORS FROM THE INSIDE :: PART 1750-STANDARD FOR DEVICES TO PERMIT THE OPENING OF HOUSEHOLD REFRI Archived 15 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Law.justia.com. Retrieved on 26 August 2013.

- Adams, Cecil (2005). "Is it impossible to open a refrigerator door from the inside?". Archived from the original on 7 July 2006. Retrieved 31 August 2006.

- "Die westdeutsche Wirtschaft und ihre fuehrenden Maenner". North Rhine Westphalia, Part III. 1975. Archived from the original on 28 April 2016 – via Flexible Magnetic Strips, Tromaflex company history (excerpt).

- US 2959832, Max Baermann, "Flexible or resilient permanent magnets", issued 1960-11-15 Archived 7 March 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- Haney, Kevin (4 December 2023). "Free Appliance Replacement: Low-Income Government Programs". www.growingfamilybenefits.com. Retrieved 5 December 2023.

Further reading

- Rees, Jonathan. Refrigeration Nation: A History of Ice, Appliances, and Enterprise in America (Johns Hopkins University Press; 2013) 256 pages

- Refrigerators and food preservation in foreign countries. United States Bureau of Statistics, Department of State. 1890.

External links

- U.S. patent 1,126,605 Refrigerating apparatus

- U.S. patent 1,222,170 Refrigerating apparatus

- The History of the Refrigerator and Freezers Archived 31 May 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- Refrigerators, Canada Science and Technology Museum

- "Walking fridge, comes when you call it". Engadget. September 2017. Retrieved 8 March 2022.