This is an old revision of this page, as edited by 75.179.181.223 (talk) at 21:57, 15 June 2007 (→English Revolution). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 21:57, 15 June 2007 by 75.179.181.223 (talk) (→English Revolution)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) For other uses, see Anarchy (disambiguation).| This article possibly contains original research. Please improve it by verifying the claims made and adding inline citations. Statements consisting only of original research should be removed. (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Anarchy (from Template:Lang-el anarchía, "without authority") refers to a human society without a government, or state. Three circumstances have been identified for this:

- societies where no state has ever existed;

- societies where an existing state has collapsed;

- societies, whether real or speculative, where the state has been consciously abolished.

Anarchy after state collapse

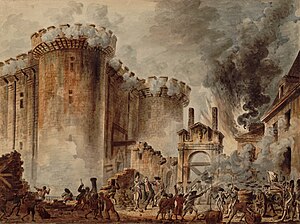

French Revolution

During the French Revolution, France entered a period of anarchy and brutal violence due to the fact that of all members of high-ruling families were killed. The reign of terror was mainly conducted by the radical egalitarian wing of the revolution. Targets were not only aristocrats but also fellow revolutionaries who were deemed too moderate, and were sent to guillotine. Thomas Carlyle, Scottish essayist of the Victorian era known foremost for his widely influential work of history, The French Revolution, wrote that the French Revolution was a war against both aristocracy and anarchy:

Meanwhile, we will hate Anarchy as Death, which it is; and the things worse than Anarchy shall be hated more! Surely Peace alone is fruitful. Anarchy is destruction: a burning up, say, of Shams and Insupportabilities; but which leaves Vacancy behind. Know this also, that out of a world of Unwise nothing but an Unwisdom can be made. Arrange it, Constitution-build it, sift it through Ballot-Boxes as thou wilt, it is and remains an Unwisdom,-- the new prey of new quacks and unclean things, the latter end of it slightly better than the beginning. Who can bring a wise thing out of men unwise? Not one. And so Vacancy and general Abolition having come for this France, what can Anarchy do more? Let there be Order, were it under the Soldier's Sword; let there be Peace, that the bounty of the Heavens be not spilt; that what of Wisdom they do send us bring fruit in its season!-- It remains to be seen how the quellers of Sansculottism were themselves quelled, and sacred right of Insurrection was blown away by gunpowder: wherewith this singular eventful History called French Revolution ends.

Armand II, duke of Aiguillon came before the National Assembly (French Revolution) in 1789 and shared his views on the anarchy:

I may be permitted here to express my personal opinion. I shall no doubt not be accused of not loving liberty, but I know that not all movements of peoples lead to liberty. But I know that great anarchy quickly leads to great exhaustion and that despotism, which is a kind of rest, has almost always been the necessary result of great anarchy. It is therefore much more important than we think to end the disorder under which we suffer. If we can achieve this only through the use of force by authorities, then it would be thoughtless to keep refraining from using such force.

Armand II was later exiled because he was viewed as being opposed to the revolution's violent tactics.

Professor Chris Bossche commented on the role of anarchy in the revolution:

In The French Revolution, the narrative of increasing anarchy undermined the narrative in which the revolutionaries were striving to create a new social order by writing a constitution.

Jamaica 1720

Sir Nicholas Lawes, Governor of Jamaica, wrote to John Robinson, the Bishop of London, in 1720:

- "As to those Englishmen that came as mechanics hither, very young and have now acquired good estates in Sugar Plantations and Indigo& co., of course they know no better than what maxims they learn in the Country. To be now short & plain Your Lordship will see that they have no maxims of Church and State but what are absolutely anarchical."

In the letter Lawes goes on to complain that these "estated men now are like Jonah's gourd" and details the humble origins of the "creolians" largely lacking an education and flouting the rules of church and state. In particular, he cites their refusal to abide by the Deficiency Act, which required slave owners to procure from England one white person for every 40 enslaved Africans, thereby hoping to expand their own estates and inhibit further English/Irish immigration. Lawes describes the government as being "anarchical, but nearest to any form of Aristocracy". "Must the King's good subjects at home who are as capable to begin plantations, as their Fathers, and themselves were, be excluded from their Liberty of settling Plantations in this noble Island, for ever and the King and Nation at home be deprived of so much riches, to make a few upstart Gentlemen Princes?.".

Somalia, 2005

Before the Islamic Courts Union took control, Somalia was the only country in the world without a functioning state (See Anarchy in Somalia). Abdo Vingaker, a Somalian living in Sweden, was quoted in an article by BBC as saying: "I am from Somalia and to live without government is the most dangerous system." The article went on to discuss the abject poverty experienced by the citizens of this country.

Anarchist communities

Main article: Anarchist communities- Barbary pirates 1500 - 1830

- Libertatia (late 1600s)

- The Free Territory (January 1919 - 1921)

- Shinmin Free Province (1929 - 1931)

- Anarchist Catalonia (July 21, 1936 - February 10, 1939)

- Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary (September 2006- June 8 2007)

- More: Past and present anarchist communities

Political philosophy

| Part of the Politics series | ||||||||

| Basic forms of government | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| List of forms · List of countries | ||||||||

Source of power

|

||||||||

Power ideology

|

||||||||

|

Power structure |

||||||||

|

Related |

||||||||

|

| ||||||||

Anarchism

Main article: anarchismAnarchists are those who advocate the absence of the state, arguing that common sense would allow for people to come together in agreement to form a functional society, allowing for the participants to freely develop their own sense of morality, ethics or principled behaviour. The rise of anarchism as a philosophical movement occurred in the mid 19th century, with its notion of freedom as being based upon political and economic self-rule. This occurred alongside the rise of the nation-state and large-scale industrial capitalism, and the corruption that came with their successes.

Although anarchists share a rejection of the state, they differ about economic arrangements and possible rules that would prevail in a stateless society, ranging from complete common ownership and distribution according to need, to supporters of private property and free market competition. For example, most forms of anarchism, such as that of anarcho-communism, anarcho-syndicalism, or anarcho-primitivism not only seek rejection of the state, but also other systems that they perceive as authoritarian, which includes capitalism, wage labor, and private property. In opposition, another form known as anarcho-capitalism argues that a society without a state is a free market system that is both voluntarist and equitable.

The word "anarchy" is often used by non-anarchists as a pejorative term, intended to connote a lack of control and a negatively chaotic environment. Whether because of this or a desire to differentiate themselves from individualist anarchists, some activists (primarily during the late nineteenth century) self-identified as libertarian socialists. In more recent times, anti-authoritarian has offered another similar self-identification. However, anarchists still argue that anarchy does not imply nihilism, anomie, or the total absence of rules, but rather an anti-authoritarian society that is based on the spontaneous order of free individuals in autonomous communities, operating on principles of mutual aid, voluntary association, and direct action.

Anthropology

See also: Anarcho-primitivismSome anarchist anthropologists, such as David Graeber and Pierre Clastres, consider several tribal hunter-gatherer societies, such as those of the Bushmen, Tiv and the Piaroa to be anarchies comparable to the projects of anarchist thought. However, other authors point out that these socities are more severe in terms of survival than modern ones.

Some more recent antropologists, such as Marshall Sahlins and Richard Borshay Lee, disagree with the notion of primitive societies as being a source of scarcity and brutalization, describing them as - in the words of Sahlins - "affluent societies".

Criticism

The evolutionary psychologist Steven Pinker writes:

Adjudication by an armed authority appears to be the most effective violence-reduction technique ever invented. Though we debate whether tweaks in criminal policy, such as executing murderers versus locking them up for life, can reduce violence by a few percentage points, there can be no debate on the massive effects of having a criminal justice system as opposed to living in anarchy. The shockingly high homicide rates of pre-state societies, with 10 to 60 percent of the men dying at the hands of other men, provide one kind of evidence. Another is the emergence of a violent culture of honor in just about any corner of the world that is beyond the reach of law. ..The generalization that anarchy in the sense of a lack of government leads to anarchy in the sense of violent chaos may seem banal, but it is often over-looked in today's still-romantic climate.

Some anarchist thinkers do not share this vision of evolution, where man was able to reinvent himself in the last ten thousand years, to better fulfill his needs. They consider that this concept represents a way our culture justifies the values of modern industrial society and inherently as the way on how civilization was able to move the individuals further from their natural necessities. Besides the consideration of authors, such as John Zerzan, to the existence in tribal society has having less violence altogether, he and other authors such as Theodore Kaczynski talk about other forms of violence on the individual in advance countries, generally expressed by the term "social anomie", that result from the system of monopolized security. These authors do not dismiss the fact that man is changing while adapting to this different social realities, but consider them an anomaly, nevertheless. The two end results being that we either disappear or become something very different, distant from what we have come to value in our nature. It has been suggested by experts that this shift towards civilization, trough domestication, has caused an increase in diseases, labor and psychological disorders. On the other hand, concerning the necessity of violence in the primitive world, anthropologist Pierre Clastres expresses that the existing violence on the primitive societies is a natural way for each community to maintain its political independence, while dismissing the state as a natural outcome of the evolution of human societies.

See also

- Anomie

- Anarchist communism

- Failed state

- Monopoly on the legitimate use of physical force

- Anarchism

- Anarchy (disambiguation)

- Freedom

- Liberty

- Voluntary association

- Mutual Aid

- Direct Action

- Anti-authoritarian

- Libertarian socialism

- Punk

- Abahlali baseMjondolo

- Amsterdam

References

- Thomas Carlyle, The French Revolution

- Duke d'Aiguillon

- Revolution in Search of Authority

- Jamaica: Description of the Principal Persons there (about 1720, Sir Nicholas Lawes, Governor) inCaribbeana Vol. III (1911), edited by Vere Langford Oliver

- BBC News: Living in Somalia's anarchy, accessed on December 29th, 2005.

- Graeber, David (2004). Fragments of an Anarchist Anthropology (PDF) (in English language). Chicago: Prickly Paradigm Press. ISBN 0-9728196-4-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - Sahlins, Marshall (2003). Stone Age Economics. Routledge. ISBN 0415320100.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - Steven Pinker's The Blank Slate, pages 330-331.

- Seven Lies About Civilization, Ran Prieur

- Industrial Society and Its Future, Theodore Kaczynski

- Zerzan, John (2002). Running on Emptiness: The Pathology of Civilization. Feral House. ISBN 092291575X.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - Zerzan, John (1994). Future Primitive: And Other Essays. Autonomedia. ISBN 1570270007.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - Industrial Society and Its Future, Theodore Kaczynski

- Freud, Sigmund (2005). Civilization and Its Discontents. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0393059952.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - Shepard, Paul (1996). Traces of an Omnivore. Island Press. ISBN 1559634316.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - The Consequences of Domestication and Sedentism by Emily Schultz, et al

- Clastres, Pierre (1994). Archeology of Violence. Semiotext(e). ISBN 0936756950.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help)

External links

- Historical Examples of Anarchy without Chaos

- On the Steppes of Central Asia

- Federation of bulgarian anarchists

- Anarchy Site

- Anarchism Fansite