This is an old revision of this page, as edited by John Smith's (talk | contribs) at 12:12, 5 August 2007. The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 12:12, 5 August 2007 by John Smith's (talk | contribs)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| The Song Dynasty宋朝 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 960–1279 | |||||||||

Northern Song in 1111 AD Northern Song in 1111 AD | |||||||||

| Capital | Kaifeng (960–1127) Lin'an (1127–1276) | ||||||||

| Common languages | Chinese | ||||||||

| Religion | Buddhism, Taoism, Confucianism | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| Emperor | |||||||||

| • 960-976 | Emperor Taizu | ||||||||

| • 1126–1127 | Emperor Qinzong | ||||||||

| • 1127–1162 | Emperor Gaozong | ||||||||

| • 1278–1279 | Emperor Bing | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

| • Zhao Kuangyin taking over the throne of the Later Zhou Dynasty | 960 960 | ||||||||

| • Jingkang Incident | 1127 | ||||||||

| • Surrender of Lin'an | 1276 | ||||||||

| • Battle of Yamen; the end of Song rule | 1279 1279 | ||||||||

| Population | |||||||||

| • Peak | 100,000,000 | ||||||||

| Currency | Jiaozi, Huizi, copper coins etc. | ||||||||

| |||||||||

The Song Dynasty (Chinese: 宋朝; pinyin: Sòng Cháo; Wade-Giles: Sung Ch'ao) was a ruling dynasty in China between 960 and 1279 AD. It succeeded the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms era, and was followed by the Yuan Dynasty. It was the first government in world history to issue paper money and the first Chinese polity to establish a permanent standing navy.

Between the 10th and 11th centuries, the population of China doubled in size. This growth came about through expanded rice cultivation in central and southern China, along with the production of abundant food surpluses. Within its borders, the Northern Song Dynasty had a population of some 100 million people.

The Song dynasty is divided into two distinct periods: the Northern Song and Southern Song. During the Northern Song (Chinese: 北宋, 960–1127), the Song capital was in the northern city of Kaifeng and the dynasty controlled most of inner China. The Southern Song (Chinese: 南宋, 1127–1279) refers to the period after the Song lost control of northern China to the Jin dynasty. During this time, the Song court retreated south of the Yangtze River and established their capital at Hangzhou. Although weakened, the Southern Song Dynasty built considerable naval strength to defend its waters, land borders, and conduct maritime missions abroad. To repel the Jin (and then the Mongols), the Song developed revolutionary new military technology enhanced by the use of gunpowder. In 1234, the Jin Dynasty was conquered by the Mongols, who subsequently took control of northern China and maintained uneasy relations with the Southern Song. After the death of the fourth Great Khan of the Mongol Empire, Mongke Khan,whose successor was Kublai Khan recalled the Mongol armies from the Middle East, and conquered the Song Dynasty in 1279. China was once again unified, but this time as part of the vast Mongol Empire. Due to numerous military defeats and the signing of insulting treaties, the Song government is perceived as weak and cowardly.

The Song Dynasty was a culturally rich period in China for the arts, philosophy, and social life. Landscape art and portrait paintings were brought to new levels of maturity and complexity since the Tang Dynasty, and social elites gathered to view art, share their own, and make trades of precious artworks. Philosophers such as Cheng Yi and Zhu Xi reinvigorated Confucianism with new commentary, infused Buddhist ideals, and emphasis on new organization of classic texts that brought about the core doctrine of Neo-Confucianism. During the Song period, people enjoyed a vibrant social and domestic life. They enjoyed public festivals such as the Lantern Festival or Qingming Festival. There were entertainment quarters in the city, such as in Hangzhou, with a constant array of puppeteers, acrobats, storytellers, singers, prostitutes, and places to relax such as tea houses, restaurants, and organized banquets. They attended social clubs in large numbers, such as tea clubs, horse-loving clubs, poetry clubs, music clubs, etc. At home they enjoyed activities such as the go board game and the xiangqi board game.

History

Main article: History of the Song DynastyTemplate:History of China - BC

Northern Song

During his reign, Emperor Taizu of Song (r. 960-976) unified China through military conquest, ending the age of the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms. Under his leadership at the imperial court in Kaifeng, he established a strong central government over the empire. Since the dynasty's conception, he ensured administrative stability by promoting the Imperial examination system of drafting state bureaucrats by skill and merit (instead of aristocratic or martial status). He promoted projects that ensured efficiency in communication throughout the empire, such as having cartographers create detailed maps of each province. He also promoted groundbreaking science and technology, by supporting such works as the astronomical clock tower designed and built by the engineer Zhang Sixun.

From the beginning, the Song Dynasty was engaged in a triangular-state arrangement of warfare and diplomacy between it and the ethnic Khitans of the Liao Dynasty, as well as the Tanguts of the Western Xia Dynasty. Starting with first emperor Taizu, the Song Dynasty attempted to use military force to quell the Liao Dynasty and recapture the Sixteen Prefectures (Liao territory considered to be a part of the Chinese domain). However, Song forces were repulsed and the Liao forces engaged in an aggressive yearly campaign into northern Song territory until 1004 AD, when the signing of the Treaty of Shanyuan ended the border clashes in the northern frontier. The Chinese were forced to pay heavy tribute to the Khitans, more significantly, the Song state also recognized the Liao state as its diplomatic equal. However, the paying of this tribute did little damage to the overall Song economy, as the Liao were heavily dependent upon importing massive amounts of goods from the Song Dynasty. With the Tanguts, the Song Dynasty managed to gain several military victories into the 11th century, culminating in the campaign of the polymath scientist, general, and statesman Shen Kuo (1031-1095 AD). However, this military campaign was ultimately a failure, and the territory gained from the Western Xia was eventually lost and returned back to their forces.

During the 11th century, political rivalries thoroughly divided members of the court due to ministers' different approaches, opinions, and policies in handling the Song's complex society and thriving economy. The idealist Chancellor Fan Zhongyan (989-1052 AD) was the first to receive a heated political backlash and reaction when he attempted to make such reforms as improving the recruitment system of officials, increasing the salaries for minor officials, and establishing sponsorship programs to allow a wider range of people to be well educated and eligible for state service. After Fan was forced to step down from his office, the later Wang Anshi (1021-1086 AD) became chancellor of the imperial court. With the backing of the new Emperor Shenzong of Song (1067-1085 AD), Wang Anshi severely criticized the education system and state bureaucracy. Seeking to resolve what he saw as state corruption and negligence, Wang implemented a series of reforms called the New Policies. These involved land tax reform, establishment of several government monopolies, support of local militias, and recreating standards for the Imperial examination to make it more practical and easier for men skilled in actual statecraft to pass. Following this, political factions were formed at court, with Wang Anshi's New Policies Group (Xin Fa), or the 'Reformers', and the other camp of ministers who followed the 'Conservative' faction, eventually led by Chancellor Sima Guang (1019-1086 AD). When one faction supplanted another in majority position of ministers at court, they would demote rival officials and exile them to govern 'backwater' frontier regions of the empire. One of the prominent victims of the political rivalry, Su Shi (1037-1101 AD), was even jailed for criticizing their political opponents.

While the central court remained politically divided and focused upon its internal affairs, alarming new events to the north in the Liao state finally caught the attention of the Song court. The Jurchen, a subject tribe within the Liao empire, rebelled against the latter, forming their own state, the Jin Dynasty (1115-1234 AD). The Song official Tong Guan (1054-1126 AD) advised the current Emperor Huizong of Song (1100-1125 AD) to form an alliance with the Jurchens, and the Jin and Song made a joint military campaign that toppled and completely conquered the Liao Dynasty by 1125. However, poor performance and the military weakness of the Song army was observed by the Jurchens, who broke the alliance with the Song and launched an invasion into Song territory in 1125 and another in 1127. The Jurchens managed to capture Kaifeng, the Song capital, the incompetent retired emperor Huizong, the succeeding Emperor Qinzong of Song, and most of his court. The remaining Song forces rallied under the self appointed Emperor Gaozong of Song (1127-1162 AD), fleeing south of the Yangtze River to establish the Song Dynasty's new capital at Lin'an (in modern Hangzhou). This Jurchen conquest of northern China and shift of capitals from Kaifeng to Lin'an marks the period of division for the Northern Song Dynasty and Southern Song Dynasty.

Southern Song

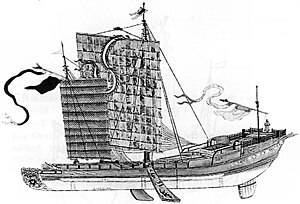

Although weakened and pushed south, the Southern Song found new ways to bolster their already strong economy and defend their state against the Jin Dynasty. They had able military officers such as Yue Fei and Han Shizhong. Through governmental sponsorship, massive shipbuilding projects, harbor improvements, construction of beacons and seaport warehouses were commenced to support maritime trade abroad, along with the bustling economies of China's major international seaports, including Quanzhou, Guangzhou, and Xiamen. To protect and support multitudes of ships sailing for maritime interests into the waters of the East China Sea and Yellow Sea (to Korea and Japan), South East Asia, the Indian Ocean, and the Red Sea, it was a necessity to establish an official permanent standing navy. The Song Dynasty therefore established China's first permanent navy in 1132, with the admiral's main headquarter stationed at Dinghai. With a permanent navy, the Song were prepared to face the naval forces of the Jin on the Yangtze River in 1161 AD, in the Battle of Tangdao and the Battle of Caishi. It was during these battles that the Song navy employed paddle wheel naval crafts armed with trebuchet catapults aboard the decks that launched gunpowder bombs. Although the Jin forces boasted 70,000 men on 600 warships, and the Song forces only 3,000 men on 120 warships, the Song Dynasty forces were victorious in both battles due to the destructive force of gunpowder explosion and fire.

Although the Song Dynasty was able to hold back the Jin, a new considerable foe came to power over the steppe, deserts, and plains north of the Jin Dynasty. The Mongols, led by Genghis Khan (r. 1206-1227 AD) initially invaded the Jin Dynasty in 1205 and 1209, in the form of large raids across their borders, but in 1211 an enormous Mongol army was assembled to invade the Jin. The Jin Dynasty was forced to submit and pay tribute to the Mongols as vassals, but when the Jin suddenly moved their capital city from Beijing to Kaifeng, the Mongols saw this as a revolt. Under the continuing leadership of Ögedei Khan (1229-1241 AD), both the Jin Dynasty and Western Xia Dynasty fell to the conquest of Mongol forces. The Mongols were once allied with the Song Chinese, but this alliance was broken when the Chinese recaptured the former imperial cities of Kaifeng, Luoyang, and Chang'an in the collapse of the Jin Dynasty. While the Mongols invaded and conquered Korea, the Abbasid Caliphate of the Middle East, and Kievan Rus' of Russia, the Mongol leader Mongke Khan was killed in 1259 AD during the Battle of Fishing Town in Chongqing, China. This prompted Hulagu Khan to pull the bulk of Mongol forces from the Middle East fighting the Egyptian Mamluks to face the Chinese instead. By 1276, most of the Song Chinese territory was captured by Mongol forces. With the Battle of Yamen on the Pearl River Delta in 1279, the Mongols finally crushed the last forces of Song resistance, as the last remaining emperor, a child, committed suicide alongside the official Lu Xiufu, who jumped off of a cliff into the sea with the boy in his arms.

Further information: List of Song EmperorsSociety, culture, economy, and technology

Society

Main article: Society of the Song Dynasty

The Song Dynasty was an era of Chinese history with a high level of administrative sophistication and social organization. Some of the largest cities in the world were found in China during this period of time (with Hangzhou boasting 1 million people), with a large empire that was for the most part run smoothly and efficiently for standards of a medieval society. People enjoyed various social clubs and marketplace entertainment in the cities, the government upheld multiple forms of social welfare programs, and although women were on a lower social tier than men (according to Confucian ethics), they nonetheless enjoyed a multitude of social and legal privileges, wielding a considerable amount of power at home and in public for a medieval society. There were many notable and well-educated women during the Song period, as it was a common practice for women to write poetry and educate their sons during their earliest youth. Examples of this would be the mother of the scientist, general, diplomat, and statesman Shen Kuo, who taught him essentials of military strategy, yet there were also women like Li Qingzhao (1084-1151), known for elegant poetry.

The civil service system enhanced by the Imperial Exams allowed for greater meritocracy, social mobility, and competitive atmosphere for those wishing to attain an official seat in government. State-gathered statistics proved that just because one had a father or other relative that had served as a high official of state, this did not guarantee one would obtain the same position of authority. Nonetheless, many felt disenfranchised by what they saw as a bureaucratic system that favored the rich who could afford the best education. One of the greatest literary critics of this was Su Shi (1037-1101), who was well known for his general criticism of the Song government.

The Song Dynasty upheld a widespread postal service to provide swift communication throughout the empire, and was modeled somewhat from the earlier Han Dynasty postal system. The central government employed thousands of postal workers, of various ranks and responsibilities, that would provide service for post offices placed along every major road at intervals of 5 li in distance (1 li in Song times = 323 m/1059 ft), while major postal stations were placed every 30 li.

During the Song Dynasty, there were many prestigious schools of learning. One of the earliest established schools of higher learning was the Yuelu Academy, founded in 976 AD. The Chinese scientist Shen Kuo was once the head chancellor of the Hanlin Academy, established during the earlier Tang Dynasty. There was also the Neo-Confucian Donglin Academy, established in 1111 AD. The philosopher Zhu Xi re-established the White Deer Grotto Academy, which had been founded earlier in the Southern Tang Dynasty.

Culture

Main article: Culture of the Song Dynasty

The Song Dynasty was a time of great intellectual flourishing and advancement for Chinese culture. The visual arts were enhanced by many evolutionary improvements, notably those in landscape painting. Many remarkable works of art were produced, as aristocratic elite gave much patronage to the arts due to their scholar-official ethic of artistic pastimes. The poet and statesman Su Shi and his associate Mi Fu partook in these affairs, often borrowing art pieces to study and copy, or if they really admired the art piece then they would offer to buy it. Poetry and literature of the Song era were enhanced with rising popularity and further development of the ci poetry form, while there was also matured development of enormous encyclopedic volumes, works of historiography, and dozens of treatises on technical subjects. Books of all sorts were printed in mass for the educated elite and a growingly literate public to enjoy and utilize. The imperial court of the emperor's palace was filled with his notable entourage of court painters, calligraphers, poets, storytellers, and others. A prime example would be the artist Zhang Zeduan (1085-1145), who painted an enormous panorama painting, Along the River During Qingming Festival. The Emperor Gaozong of Song also initiated an enormous art project known as the Eighteen Songs of a Nomad Flute.

In terms of philosophy, although Buddhism had waned in influence, it was still kept active in the arts, in charities from monasteries, and its influence upon the budding movement of Neo-Confucianism, led by those such as Cheng Yi (1033-1107) and Zhu Xi (1130-1200). Buddhism's continuing influence can be seen in painted artwork such as Lin Tinggui's Luohan Laundering. Mahayana Buddhism influenced the likes of Fan Zhongyan and Wang Anshi with the concept of ethical universalism, while Buddhist metaphysics had a deep impact upon the pre-Neo-Confucian doctrine of Cheng Yi. The philosophical work of Cheng Yi in turn influenced Zhu Xi, who was not accepted by his peers in his own time, yet his emphasis of the Confucian classics outlined in his Four Books formed the base of Neo-Confucian doctrine. Zhu Xi's Four Books and his commentary on them became standard requirements of study for students attempting to pass the Imperial examinations by the mid 13th century. While China wholly adopted Neo-Confucianism, so did other countries of East Asia as well, including Japan and Korea. Zhu Xi's teaching in both of these countries became known as the Shushigaku (朱子学, School of Zhu Xi) of Japan, and in Korea the Jujahak (주자학).

Economy

Main article: Economy of the Song Dynasty

The Song Dynasty economy was one of the most prosperous and advanced economies in the medieval world. Song Chinese invested their funds in joint stock companies with guild heads and invested money in multiple sailing vessels at a time for assurance of monetary gains of interest from overseas trade. The Song economy was stable enough to produce over a hundred million kilograms (over two hundred million pounds) of iron product a year, much of which was reserved for the military to use in crafting weapons and armor for troops. Annual outputs of minted copper currency in 1085 alone reached roughly 6 billion coins. However, the most notable advancement in the Song economy was the establishment of the world's first government issued paper-printed money, known as Jiaozi (see also Huizi). During the Song Dynasty, independent and government sponsored industries were developed to meet the needs of a growing population. For example, for the printing of paper money alone, the Song court established several government-run factories in the cities of Huizhou, Chengdu, Hangzhou, and Anqi. The size of the workforce employed in these paper money factories were quite large, as it was recorded in 1175 AD that the factory at Hangzhou alone employed more than a thousand workers a day. Chinese economic power was felt heavily upon foreign economies abroad, as even the Moroccan Muslim geographer al-Idrisi wrote in 1154 AD of the prowess of Chinese merchant ships in the Indian Ocean, and their annual voyages that brought iron, swords, silk, velvet, porcelain, and various textiles to places such as Aden (Yemen), the Indus River, and the Euphrates River in modern-day Iraq. Foreigners, in turn, had an impact on Chinese economy. For example, many Muslims went to China to trade, and dominated the import and export industry. Sea trade abroad to the South East Pacific, the Hindu world, the Islamic world, and the East African world brought merchants great fortune, but there was risk involved in such long overseas ventures. In order to reduce the risk of losing money instead of gaining it on maritime trade missions abroad:

investors usually divided their investment among many ships, and each ship had many investors behind it. One observer thought eagerness to invest in overseas trade was leading to an outflow of copper cash. He wrote, "People along the coast are on intimate terms with the merchants who engage in overseas trade, either because they are fellow-countrymen or personal acquaintances... money to take with them on their ships for purchase and return conveyance of foreign goods. They invest from ten to a hundred strings of cash, and regularly make profits of several hundred percent.

Technology

Main article: Technology of the Song Dynasty

The Song Dynasty was a remarkably innovative age for medieval technology and science, both applied for the benefit of Chinese society and military defense.

Advancements in weapons technology enhanced by Greek fire and gunpowder (including the evolution of the early flamethrower, explosive grenade, firearm, cannon, and land mine) enabled the Chinese to ward off their militant enemies until their ultimate collapse in the late 13th century. The Wujing Zongyao manuscript of 1044 AD was also the first book in history to provide formulas for blackpowder and their specified use in different types of bombs. By the early to mid 14th century the firearm and cannon could also be found in Europe, India, and the Middle-East, in the early age of gunpowder warfare.

Polymath figures such as the statesmen Shen Kuo and Su Song embodied advancements in all fields of study, including biology, botany, zoology, minerology, mechanics, horology, astronomy, pharmaceutical medicine, archeology, mathematics, magnetics, navigation, art criticism, and more. Shen Kuo was known for his writings about true north and the magnetic compass, navigation at sea, his description of Bi Sheng's invention of movable type printing, the application of a drydock to repair boats, analysis of treatises on engineering and architecture, among many other things. Su Song was best known for his horology treatise, written chiefly about his hydraulic-powered, 40-foot-tall astronomical clock tower built in Kaifeng. The clock tower featured large astronomical instruments of the armillary sphere and celestial globe, both driven by an escapement mechanism (roughly two centuries before the verge escapement could be found in clockworks of Europe). In addition, Su Song's clock tower featured the world's first endless power-transmitting chain drive, an essential mechanical device found in many practical uses throughout the ages, such as the bicycle.

Like in earlier periods (ie. since the Han Dynasty) when the state needed to effectively measure distances traveled throughout the empire, the Song Chinese relied on the mechanical odometer device. The Chinese odometer came in the form of a wheeled-carriage, its inner gears functioning off the rotated motion of the wheels, and specific units of distance marked by the mechanical striking of a drum or bell for auditory alarm. An 11th century Song government minister (Chief Chamberlain Lu Dao-long) writing about the Song era odometer's specifications is quoted extensively in the historical text of the Song Shi. The odometer was also combined with the complex mechanical device of the South Pointing Chariot (used for navigation) during the Song Dynasty. This device incorporated a differntial gear that allowed a figure mounted on the vehicle to always point in the southern direction, no matter how the vehicle's wheels' turned about.

There were considerable advancements in civil engineering and nautics technologies during the Song Dynasty. This included the invention of the pound lock for canal systems (allowing different water levels for separated segments of the canal), watertight bulkhead compartments for ships (allowing damage to the hull without sinking), and the introduction of the magnetic mariner's compass for navigation at sea.

The advancement of movable type printing by the artisan Bi Sheng (990-1051 AD) enhanced the already widespread use of woodblock printing for printing thousands of documents and volumes of written literature that was consumed eagerly by a growingly literate public.

Further information: History of typography in East AsiaArchitecture

Main article: Architecture of the Song Dynasty

Architecture during the Song period reached great heights of sophistication. There were several authors of literary works outlining the field of architectural layouts, craftsmenship, and engineering, such as Yu Hao and Shen Kuo in the 10th and 11th centuries, respectively. The architect Li Jie, who published the Yingzao Fashi ('Treatise on Architectural Methods') in 1103 AD, greatly expanded upon the works of Yu Hao and outlined the standard building codes used by the central government agencies and by craftsmen throughout the empire. He outlined the standard methods of construction, design, and applications of moats and fortifications, stonework, greater woodwork, lesser woodwork, wood-carving, turning and drilling, sawing, bamboo work, tiling, wall building, painting and decoration, brickwork, and glazed tile making.

Grandiose building projects were supported by the government, including the erection of towering Buddhist Chinese pagodas and enormous bridges (wood or stone, trestle or segmental arch bridge). Many of the pagoda towers built during the Song period were erected at heights tall enough to exceed 10 stories. Some of the most famous of these are the Iron Pagoda (1049 AD) of the Northern Song, as well as the Liuhe Pagoda (1165 AD) of the Southern Song, yet there were many others. The tallest is certainly the Liaodi Pagoda of Hebei built in the year 1055, towering 84 m (275 ft) in total height. Some of the bridges reached lengths of 1220 m (4000 ft), with many being wide enough to allow two lanes of cart traffic to travel simultaneously over a waterway or ravine. In terms of architecture, the profession of the architect, craftsman, carpenter, and building engineer weren't seen as high professions equal to the likes of a Confucian scholar-official. Architectural knowledge was passed down orally for thousands of years in China, from a father craftsman to his son (if the son wished to continue the legacy of his father). However, architectural engineering schools were also known to have existed during the Song period, perhaps one prestigious school headed by the renowned bridge-builder Cai Xiang (1012-1067) in medieval Fujian province.

Further information: Chinese architectureSee also

- List of Song Emperors

- History of China

- Bao Qingtian

- Battle of Xiangyang

- Battle of Tangdao

- Battle of Caishi

- Wen Tianxiang

- Islam during the Song Dynasty

Related articles

- Architecture of the Song Dynasty Template:GA-symbol

- Culture of the Song Dynasty Template:GA-symbol

- Economy of the Song Dynasty Template:GA-symbol

- History of the Song Dynasty Template:GA-symbol

- Society of the Song Dynasty

- Technology of the Song Dynasty

Notes

- ^ Ebrey et al., 156.

- ^ Ebrey et al., 167.

- China. (2007). In Encyclopædia Britannica. From Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved on 2007-06-28

- Needham, Volume 3, 518.

- Needham, Volume 4, Part 2, 469-471.

- Mote, 69.

- Mote, 70-71.

- Ebrey et al., 154.

- Sivin, III, 8.

- Sivin, III, 9.

- ^ Ebrey et al., 163.

- ^ Ebrey et al., 164.

- Sivin, III, 3-4.

- ^ Ebrey et al., 165.

- Wang, 14

- Sivin, III, 5.

- ^ Paludan, 136.

- Shen, 159-161.

- ^ Needham, Volume 4, Part 3, 476.

- Levathes, 43-47

- Needham, Volume 1, 134.

- Ebrey et al., 235.

- ^ Ebrey et al., 236.

- ^ Needham, Volume 1, 139.

- Ebrey et al., 240.

- Ebrey et al., 170.

- ^ Ebrey et al., 171.

- ^ Sivin, III, 1.

- ^ Ebrey et al., 162.

- ^ Needham, Volume 4, Part 3, 35.

- Needham, Volume 4, Part 3, 36.

- ^ Ebrey et al., 168.

- Wright, 93.

- Ebrey et al., 169.

- Ebrey et al., 157.

- Ebrey et al., 158.

- ^ Needham, Volume 5, Part 1, 48.

- Shen, 159-161.

- BBC article about Islam in China "Islam in China (650–present): Origins". Religion & Ethics - Islam. BBC. Retrieved 2007-08-01.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help) - Ebrey et al., 159.

- Needham, Volume 5, 80.

- Needham, Volume 5, 82.

- Needham, Volume 5, 220-221.

- Needham, Volume 5, Part 7, 192.

- Needham, Volume 5, Part 7, 117.

- Needham, Volume 1, 136.

- Needham, Volume 4, Part 2, 446.

- Needham, Volume 4, Part 2, 445.

- Needham, Volume 4, Part 2, 448.

- Needham, Volume 4, Part 2, 111.

- Needham, Volume 4, Part 2, 281-282.

- Needham, Volume 4, Part 2, 291.

- Guo, 4.

- Guo, 6.

- Needham, Volume 4, Part 3, 85.

- Needham, Volume 4, Part 3, 151.

- Needham, Volume 4, Part 3, 153.

a: During the reign of the Song Dynasty the world population grew from about 250 million to approximately 330 million, a difference of 80 million. Please also see Medieval demography.

b: For the history of paper-printed money, please see banknote.

c: Despite the establishment of permanent standing navy in Song Dynasty, China already had a long naval history prior to the Song, see Naval history of China.

d: As opposed to the previous Han and Tang Dynasty, each of which boasted roughly 50 million inhabitants

e: See the technology section for more information.

References

- Ebrey, Walthall, Palais (2006). East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. ISBN 0-618-13384-4.

- Hall, Kenneth (1985). Maritime trade and state development in early Southeast Asia. Hawaii: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-8248-0959-9.

- Levathes (1994). When China Ruled the Seas. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-70158-4.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|fist=ignored (help) - Mote, F.W. (1999). Imperial China: 900-1800. Harvard:Harvard University Press.

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 1, Introductory Orientations. Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd.

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 3, Mathematics and the Sciences of the Heavens and the Earth. Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd.

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Physics and Physical Technology, Part 2: Mechanical Engineering. Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd.

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Physics and Physical Technology, Part 3: Civil Engineering and Nautics. Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd.

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 5, Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 7: Military Technology; The Gunpowder Epic. Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd.

- Paludan, Ann (1998). Chronicle of the Chinese Emperors. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0500050902.

- Guo, Qinghua. "Yingzao Fashi: Twelfth-Century Chinese Building Manual," Architectural History: Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians of Great Britain (Volume 41 1998): 1-13.

- Shen, Fuwei (1996). Cultural flow between China and the outside world. Beijing: Foreign Languages Press. ISBN 7-119-00431-X.

- Sivin, Nathan (1995). Science in Ancient China. Brookfield, Vermont: VARIORUM, Ashgate Publishing.

- Wang, Lianmao (2000). Return to the City of Light: Quanzhou, an eastern city shining with the splendour of medieval culture. Fujian People's Publishing House.

- Wright, Arthur F. (1959). Buddhism in Chinese History. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Further reading

- Gascoigne, Bamber (2003). The Dynasties of China: A History. New York: Carroll & Graf. ISBN 1-84119-791-2.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Giles, Herbert Allen (1939). A Chinese biographical dictionary (Gu jin xing shi zu pu). Shanghai: Kelly & Walsh. (see here for more)

- Gernet, Jacques (1982). A history of Chinese civilization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-24130-8.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Kruger, Rayne (2003). All Under Heaven: A Complete History of China. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-470-86533-4.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Tillman, Hoyt C. and Stephen H. West (1995). China Under Jurchen Rule: Essays on Chin Intellectual and Cultural History. New York: State University of New York Press.

External links

| Preceded byFive Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms | Song Dynasty 960-1279 |

Succeeded byYuan Dynasty |