This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Everyking (talk | contribs) at 16:49, 12 June 2005 (→Various forms of messianism). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 16:49, 12 June 2005 by Everyking (talk | contribs) (→Various forms of messianism)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)Chabad Lubavitch, or Lubavich, is a large branch of Hasidic Judaism founded by Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liadi. It is also known simply as Chabad (חבד) a Hebrew acronym for "ח Wisdom- ב Understanding- ד Knowledge", or as Lubavitch (ליובאוויטש), the city that served as headquarters for over a century. In Russian, the name means "city of brotherly love".

Its adherents, or Chasidim, known as "Lubavitchers", are Orthodox Jews belonging to Hasidic Judaism as defined by the Chabad traditions. In Israel they are known as Chabadnikim ("Chabadniks"), a derivation of the movement's second name.

Like all Hasidim they follow the teachings and customs of halakha (Jewish law and custom) as taught by their own Rebbes (rabbis, leaders) starting from the founder of Hasidism, Rabbi Israel Baal Shem Tov. In this case, the teachings of the Baal Shem Tov are traced through their founder's master works known as The Tanya and the Shulchan Aruch HaRav. Similarly, Chabad attaches importance to singing Hasidic nigunim (tunes), either with or without words and following precise customs of their leaders.

Until the death of the 7th Chabad leader, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson in 1994, they were governed by a succession of leaders, each descended from the founder of the movement. The death of their Rebbe in 1994 came as a great shock to members of the movement, since many believed that he was the Moshiach - the Jewish Messiah, and would be revealed to the world as such. Schneerson, who was childless, did not appoint a successor; Chabad Hasidim still consider him to be their leader and Rebbe.

Early origins

The movement originated in Belarus in Eastern Europe. Chabad traces its roots back to the beginnings of Hasidic Judaism:

- Rabbi Israel ben Eliezer 1698 - 1760 was known as the Baal Shem Tov (abbreviated as BeSHT, meaning "Master of the Good Name"). He based his nascent movement in Mezibush, Ukraine.

- Rabbi Dovber of Mezeritch (d. 1772) was the Baal Shem Tov's leading disciple. He was well-versed in the Lurianic Kabbalah. Upon the death of the BeSHT he assumed the leadership of the movement that would become known as Hasidism.

Rebbes of Chabad

Founder

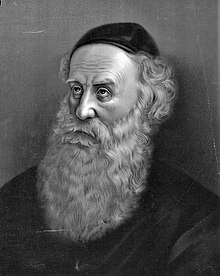

- Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liadi 1745 - 1812, son of Rabbi Boruch, was a student of Dovber of Mezeritch and founded the Chabad house of Hasidism. This name is not truly of Eastern European origin; "Shneur Zalman" was a linguistic corruption of "Senor Solomon" which came into usage when Spanish Jews were expelled from Spain and strengthened their links with Eastern Europe. His family took his first name as their family name (surname) of "Schneersohn". He defined the direction of his movement and influenced Hasidic Judaism through his master works the Tanya, which is primarily mystical and in line with the Zohar, and his authoritative work on Jewish law known as the Shulchan Aruch HaRav. He was a recognized posek (authority in Jewish law), and is often cited in other important works such as the Mishnah Berurah and the Ben Ish Chai.

Leadership

- Rabbi Dovber 1773 - 1827, son of Shneur Zalman.

- Rabbi Menachem Mendel 1789 - 1866, grandson of Shneur Zalman and son-in-law of Dovber.

- Rabbi Shmuel 1834 - 1882, son of Rabbi Menachem Mendel.

- Rabbi Sholom Dovber 1860 - 1920, son of Rabbi Shmuel.

- Rabbi Joseph Isaac Schneersohn 1880 - 1950, only son of Sholom Dovber.

- Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson 1902 - 1994, (his family name does not have the "h" of "...sohn" as he was a cousin from a different branch of the family), sixth in paternal line from Rabbi Menachem Mendel, and son-in-law of Joseph Isaac.

The names "Schneersohn" and "Schneerson" began as patronymics by Shneur Zalman's descendants. The first form of this name was "Shneuri" (Hebrew for "of Shneur") This was later changed to "Schneersohn".

Origin of name

Chabad

The names Chabad and Lubavitch each have a history. Chabad is a Hebrew acronym for Chochma (Wisdom), Bina (Understanding), and Da'as (Knowledge), that was chosen early on by its founder, the first Rebbe, Shneur Zalman of Liadi. The name Chabad reflects the intellectual accessibility of the mystical teachings of the Kabbalah. Rabbi Shneur Zalman is the author of the seminal Hassidic work, Tanya, as well as the Shulchan Aruch Ha'Rav - a code of Jewish Law.

Chabad is sometimes written as Habad in English, and in all the phonetic equivalents of the name in all the countries they operate in. Thus, as an example, Jabad is the Spanish form, particularly important to the Jews of Latin America, most notably Argentina, which has the largest concentration of Spanish speaking Jews anywhere in the world and therefore has a large Lubavitch presence as well.

Lubavitch

Lubavitch is the name of a small town in Russia meaning "town of love". It was Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liadi who founded the movement, but his son established court in Lubavitch, and the name stuck. In Hasidic Judaism, a dynasty normally takes its name from the town in Eastern Europe where it was born and originated. The followers of Lubavitch place great emphasis on the value and meaning of their group name and town of origin. They say that this evokes, symbolizes and embodies who they are.

The movement

In 19th and 20th century Russia Chabad had a large following and had a sizeable network of yeshivoth called Tomchei Temimim. Most of this system was destroyed by Bolshevik governments and the German invasion in 1942. The then current Rebbe Joseph Isaac Schneersohn had been living in Warsaw, Poland, and with the lobbying of many Jewish leaders on his behalf, he was finally granted diplomatic immunity and given safe conduct to go via Berlin, then to Riga, and then on to New York City where he arrived on March 19 1940. His son-in-law and cousin Menachem Mendel Schneerson, who had been living in Paris, France, since 1933, escaped from France in 1941 and joined his father-in-law in the Crown Heights section of Brooklyn, New York City. Menachem Mendel Schneerson, after becoming the Rebbe himself, and following an initiative of the previous Rebbe, spurred the movement on to what has become known as shlichus (outreach work). As a result, Chabad shluchim (emissaries) have moved all over the world with a mission of helping all Jews, regardless of denomination or affiliation, to learn more about their Jewish heritage, and Judaism as practiced by Chabad.

The movement has trained and ordained thousands of rabbis, educators, ritual slaughterers, and ritual circumcisers, who are all accompanied by equally motivated spouses and typically large families, all of whom aim to fulfill their mandate of Jewish outreach, education, and revival. They look for and recruit Jews who want to join them, encourage Jews to strengthen their commitment to Judaism, and assist in supporting the religious needs of hundreds of thousands of Jews worldwide. They are the originators of, and major players in, the Teshuva movement, which encourages Jews alienated from their religion to become more Jewishly aware and religiously observant.

Schneerson greatly emphasized spreading awareness of the coming of Moshiach and preparing for his imminent arrival. Soem of the points Schneerson stressed in his teaching include:

- Belief in the imminent coming of Moshiach is a fundamental Jewish belief as explained by the Rambam.

- The Geula, or the Era of Redemption, is the culmination of the spiritual work since the Creation of the world.

- Jews prepare and pave the way for the coming of Moshiach and the Geula by doing mitzvoth - the 613 commandments, as detailed in the Torah

- Non-Jews have seven mitzvoth, called the Noahide Laws, that they should become aware of and practice.

Often when asked what remains to be done to bring Moshiach (the messiah), Schneerson answered that we need to perform "Acts of Goodness and Kindness," now a popular catchphrase. Rabbi Schneerson intended that Moshiach awareness be an essential part of everything we do, and thus it is unusual for any Chabad function to be without mention of the desire for the immediate Redemption.

The worldwide headquarters of the Chabad movement is 770 Eastern Parkway in the neighborhood of Crown Heights, Brooklyn, referred to as "770" by Lubavitchers who deem the number to have great mystical significance.

Controversies

History of Controversy

Since its inception, Hasidism was the center of much controversy within the Jewish community. The founder of Hasidism, Rabbi Israel Baal Shem Tov was a populist preacher and Kabbalist virtually unknown to the accepted Rabbinate at the time. His quickly growing popularity and novel interpretations of the Torah and halakha (Jewish law) quickly caused a growing backlash by established Rabbis who called themselves mitnagdim (lit. opposers). Hasidim were accused of idolatry, false messianism and laxity in observance of halakha. This opposition was led by Rabbi Eliyahu Kramer, known as the Vilna Gaon.

After the death of the Baal Shem Tov's successor, Rabbi Dovber of Mezeritch, Hasidism split into many groups. Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liadi is believed by Chabad Hasidim to be the rightful heir and successor of Rabbi Dovber of Mezritch. During the lives of Rabbi Shneur Zalman and his son Dovber, the controversies between the Hasidim and Mitnagdim intensified in many ways. Subjects of the disagreement were the rules for ritual slaughter and the conduction and phrasing of prayers, but rapidly involved many other aspects of Jewish life. As a result, Rabbi Shneur Zalman and his followers were subjected to bans and persecution. Finally, a prominent member of the mitnagdim informed the Russian government that Rabbi Shneur Zalman was encouraging his followers to send money to Palestine. Palestine was a part of the Ottoman Empire, which was at war with Russia. Rabbi Shneur Zalman was arrested for treason. His subsequent release on 19 Kislev is celebrated by Chabad Hasidim as the New Year of Hasidism and divine vindication of the movement.

There was brief reproachment between Chabad, other Hasidim and the mitnagdim during the tenure of Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneersohn, the grandson of Rabbi Shneur Zalman. However, Chabad continued to be controversial in all of its generations.

Controversy during the Seventh Rebbe's life

Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, the seventh Chabad leader, took the reins of the sect shortly after World War II and became their Rebbe. At the time, many believed that Orthodox Judaism was about to die. Schneerson believed that the coming of the Messiah was soon to come. At the speech where he accepted leadership, he proclaimed the defining theme of his tenure. He stated that his purpose as the seventh Rebbe was to complete the work of bringing the Jewish Messiah. He further stated that the previous Rebbe had not finished this work, but because of the unusual character of his self-sacrifice was still present to lead the charge in bringing about the Messianic Age. "Beyond this, the Rebbe will bind and unite us with the infinite Essence of G-d... When he redeems us from the exile with an uplifted hand and the dwelling places of all Jews shall be filled with light... May we be privileged to see and meet with the Rebbe here is this world, in a physical body, in this earthy domain - and he will redeem us" (Basi L'Gani 1951).

Schneerson renounced the traditionally insular or assimilationist way of life espoused by many Jews in the United States. He encouraged growing long beards, women wearing wigs and other overt signs of religiosity. His followers held public Hannukah celebrations, encouraged secular Jews to put on tefillin in public and made themselves highly visible in their Jewish observance. This caused a backlash from both liberal and traditional factions of the Jewish establishment. Chabad fought battles in court all the way to the United States Supreme Court against the American Jewish Congress over the display of a public Menorah. Many prominent Rabbis were staunchly opposed to allowing secular Jews to wear tefillin, as they believed it to be a desecration. The controversies over the role of a tzadik and the coming of the Jewish Messiah continue to rage.

Relationship between God, the Rebbe and his followers

| The neutrality of this section is disputed. Relevant discussion may be found on the talk page. Please do not remove this message until conditions to do so are met. (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Before Schneerson's death, the beliefs of Chabad Hasidim had become extremely controversial among other Orthodox Jews. All Hasidic Jews are adherents of Kabbalah, esoteric Jewish mysticism. Among Kabbalists the role of the tzadik ("righteous" or "saintly" person) is stressed more than among non-Kabbalists. A tzadik is believed to have close connection with God, acting as a "chariot for the Divine" (מרכבה לשכנה), both in life and after death. (Tanya Epistle 27)

Many Jewish sources stress prayer directly to God, and not through an intermediary. However, Hasidism has stressed the ability of tzadik to act as an intermediary with God on their behalf. Hasidim continue to ask for such intervention even after the death of their Rebbe and often visit their burial places to pray for blessings. The stipulation in such prayer is that one must recognize that the tzadik is not God. Among Hasidim all rebbes are held to be tzadikim and revelation of God.

Schneerson's teachings developed this theology into a new direction, holding that "It is not possible to ask a question about a go-between, since this is the essence of God Himself, as He has clothed Himself in a human body" (Likutei Sichos II:510-511). Schneerson holds that a tzadik, who does whatever God wants, effectively nullifies their own soul as his soul joins with the will of God. In this view the words of the tzadik are the words of God (Pavzener, based on Tanya Chapter 2).

Schneerson makes this explicit "Just as 'God and the Torah and the Jews are One', means not just that the Jews are connected to the Torah and to God, but literally they are all one, so too is the connection of Chassidim and their Rebbe, they are not like two things that become united but rather they become literally one. Therefore, to a Chosid, him and the Rebbe and God are one entity." This view has been rejected as heretical by some non-Hasidic Orthodox groups since the beginnings of Hasidism.

Few, if any, Chabad Hasidim disagree with this, since the statements of a Rebbe define the Hasidic group. Critics have claimed that such views contradict the Jewish principles of faith since the publication of the first Hasidic book, Toldot Yaakov Yosef in 1780.

Various forms of messianism

During the later years of his life Schneerson's teachings were widely interpreted to mean that he was claiming to be the Messiah. Shortly before the time of his death the majority of Chabad Hasidim viewed him as being the presumptive Messiah.

The development of this messianism and its impact on Chabad in specific — and Orthodox Judaism in general — has been the subject of much discussion in the Jewish press, as well as within the pages of peer-reviewed journals. Few within Chabad deny the existence or extent of this messianism; the defenders of these beliefs hold rather it is simply true that Menchem Mendel Schneerson is indeed the messiah and that he will return from the dead immediately.

Vociferous opponents of the "meschichist" ("messianist") approach were some of the prominent roshei yeshiva (deans of Talmud colleges), such as Rabbi Elazar Menachem Shach, dean of the Ponovezh yeshiva in Israel, who had condemned Chabad beliefs even before Schneerson's death. He was the leader of a group that had historically been at odds with all Hasidim, including Chabad, though from the 20th century onwards they worked quite closely together in organizations such as Agudath Israel, and Shach himself had not criticized any other Hasidic group in this way.

The messianic response has taken various forms amongst Chabad members:

- Some Chabad Hasidim hold that Schneerson was the best candidate for Messiah in his generation, but that we now know it was mistaken to believe that he was the Messiah. Rather, he could have been the messiah if God willed it to be so, but it was not to be. As such, the Messiah will come nonetheless as some other great leader.

- Many Chabad Hasidim hold that the classic meaning of death does not apply to a truly righteous person such as Schneerson, as his soul was closer to God than that of an ordinary human being. In this view Schneerson never died, and is still alive in some way that ordinary humans cannot detect. He will return in a more obvious way to proclaim his messiahship (see e.g. Rabbi Levi Yitzchack Ginsberg, of Kfar Chabad Yeshiva, in his book Mashiah Akhshav, volume IV, 1996). Many Chabad Hasidim refuse to put the typical honorifics for the dead (e.g. zt"l or Zecher Tzaddik Livrocho, "may the memory of the righteous be for a blessing") after Schneerson's name.

- Many Chabad Hasidim hold that the Schneerson literally will return from the dead amidst a general bodily resurrection of the dead, and will be proclaimed as Messiah. Although this position is considered by many to be a innovation in Jewish theology, some Chabad Hasidim have developed an extensive literature of prooftexts attempting to show that this is what previous rabbinic literature actually meant.

- A few Chabad followers hold that Schneerson is God incarnate, and worship him as such.

Responses from various Jewish spokespeople have been aimed specifically at the last two expressions of messianism. Longtime critic Allan Nadler (2001) and Rabbi Chaim Dov Keller (1998) warn that Chabad has moved its focus from God to Schneerson to the point that they "worship him".

In response to criticism, most members of Chabad themselves insist that this latter group is a tiny aberration, and inflated by their critics in order to embarrass Chabad. Non-Chabad Jews agree that this group is statistically small. However, many are concerned that this position seems to be a logical result of the mainstream Chabad belief and results in neo-Christian beliefs. Rabbi Jack Riemer (Conservative Judaism), for example, refers to the literature of meschichist Chabad Jews as Christian, and as being the same as that of Jews for Jesus tract. Professor Jacob Neusner (Conservative) similarly writes (2001) that Chabad has invented "halachic Christianity".

References

- Berger, David. "The Fragility of Religious Doctrine: Accounting for Orthodox Acquiescence in the Belief In A Second Coming," Modern Judaism, Vol. 22, p.103-114, 2002

- Berger, David. The Rebbe, the Messiah, and the Scandal of Orthodox Indifference, Littman Library of Jewish Civilization, 2001 (ISBN 1874774889)

- Dalfin, Chaim. Attack on Lubavitch: A Response, Jewish Enrichment Press, February 2002 (ISBN 1880880660)

- Fishkoff, Sue. The Rebbe's Army: Inside the World of Chabad-Lubavitch, Schocken, 2003 (ISBN 0805241892)

- Hoffman, Edward. Despite All Odds: The Story of Lubavitch. Simon & Schuster, 1991 (ISBN 0671677039)

- Keller, Chaim Dov. "G-d - Centered or Rebbe/Messiah - Centered: What is Normative Judaism?", Jewish Observer, March, 1998

- Mindel, Nissan. The philosophy of Chabad. Chabad Research Center, 1973 (ASIN B00070MRV8)

- Nadler, Allan. Last Exit to Brooklyn: The Lubavitcher's powerful and preposterous messianism. The New Republic May 4, 1992.

- Nadler, Allan. A Historian's Polemic Against 'The Madness of False Messianism' The Forward Oct. 19, 2001.

- Neusner, Jacob. A Messianism That Some Call Heresy. Jerusalem Post October 19, 2001

- Pavzener, Avraham. Al HaTzadikim (Hebrew). Kfar Chabad. 1991

- Riemer, Jack. Will the Rebbe Return?. Moment Magazine February 2002.

- Schneerson, Menachem Mendel. On the Essence of Chasidus: A Chasidic Discourse by Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson of Chabad-Lubavitch. Merkos L'Inyonei Chinuch, 2003 (ISBN 0826604668)

- Schochet, Rabbi J. Immanuel. G-d Centered or Machloket-Centered: Which is Normative Judaism? A Response to Rabbi Chaim Dov Keller of Chicago. Algemeiner Journal.

- Shaffir, William. When Prophecy is Not Validated: Explaining the Unexpected in a Messianic Campaign. The Jewish Journal of Sociology. Vol.XXXVII, No.2, Dec. 1995

- Student, Gil. Can the Rebbe Be Moshiach?: Proofs from Gemara, Midrash, and Rambam that the Rebbe cannot be Moshiach, Universal Publishers, 2002, (ISBN 1581126115)

See Also

- List of Hasidic dynasties

- Crown Heights

- Kehot Publication Society

- Menachem Mendel Schneerson

- Mitzvah tank