This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Hetoum I (talk | contribs) at 05:29, 5 September 2007 (yep, battle of baku includes only Armenians who died or got deported at the battle of baku, and stalingrad includes only soviets who were casualties in the battle). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 05:29, 5 September 2007 by Hetoum I (talk | contribs) (yep, battle of baku includes only Armenians who died or got deported at the battle of baku, and stalingrad includes only soviets who were casualties in the battle)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| Battle of Baku | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Armenian-Azerbaijani War & Caucasus Campaign | |||||||

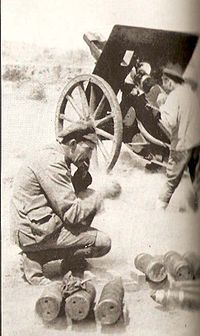

Armenian defenders of Baku man a 4-inch howitzer. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

File:Dtr.JPG Central Caspian Dictatorship | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

File:Dtr.JPG General Dokuchaev File:Dtr.JPG Colonel Avetisov | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

14,000 infantry 500 cavalry 40 guns |

1,000 infantry 1 artillery battery 1 machine gun section 3 armored cars 2 planes File:Dtr.JPG Baku Army 6,000 infantry 40 guns 600 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Total: 2,000 |

200 File:Dtr.JPG Baku Army ? Armenian Civilians Up to 50,000 killed and deported | ||||||

The Battle of Baku (Template:Lang-az, Template:Lang-ru), also referred to as the Defense of Baku (Template:Lang-hy) was the final battle of the Caucasus Campaign but just the beginning phase of Armenian-Azerbaijani War.

It took place in the vicinity of Baku, in September 1918 . The Ottoman-Azerbaijani-Dagestani forces of the Army of Islam led by led by Nuri Pasha won the battle against a coalition of British, Armenian and White Russian forces led by Lionel Dunsterville.

Background

Following the abdication of the Tsar in 1917, the Caucasus Front collapsed, and Russian troops evacuated Armenia. Batum and Van were captured by the Ottoman Empire.

A number of Russian troops left through Anzali, but 2 parties remained. General Nikolai Baratov remained in Hamadan with a substantial force, who could not evacuate before winter. He waited for spring. At Kermanshah, a Russian colonel of Ossetian origin named Lazar Bicherakhov remained with 10,000 faithful troops. Both men were supplanted with British liaison officers.

As a result of this collapse, the roughly 800 miles between Mesopotamia and the Caucasus were open for an Ottoman force to pass through. The situation was especially dire in the Caucasus, where Enver Pasha had planned to place Armenia, Georgia and Azerbaijan under Turkish suzerainty as part of his Pan-Turanian plan. This would give the Central Powers numerous natural resources, including the oilfields of Baku. The control of the Caspian would open the way to further expansion in Central Asia, and possibly British India.

Formation of the Dunsterforce

Threatened by the possibility, the British chose to send a mission of officer and instructors to the region to counter the Turks. The belief behind the mission was that the three republics would fight the Turks to avoid massacre. It was hope that his would keep the Caucasus-Tabriz front intact and put a stop on Enver’s Pan-Turanian plans.

The British mission was headed by Major-General Lionel Dunsterville, who arrived to take command of the mission force in Baghdad on January 18, 1918. The first few members of the force were already assembling.

He was set to proceed from Mesopotamia, through Persia to the port of Anzali, then board ship to Baku and on. Dunsterville set out from Baghdad on January 27, 1918, with 4 NCO’s and batmen in 41 Ford vans and cars.

However, the country on their road was overrun by the anti-British Jangalis under Mirza Kuchak Khan, a force about 5,000 strong. On February 17, he arrived at Anzali. Here he was denied passage to Baku by local Bolsheviks, who cited the change in the political situation.

March massacres

Main article: March DaysMeanwhile the arrest of General Talyshinski, the commander of the Azerbaijani division, and some of its officers all of whom arrived in Baku on March 9, increased the anti-Soviet feelings among the city's Azeri population. On 30 March the Soviet based on the unfounded report that the Muslim crew of the ship Evelina was armed and ready to revolt against the Soviet, disarmed the crew which tried to resist This led to a 3 days of inter ethnic warfare referred to as the March Days, which resulted in the massacre of up to 12,000 Azerbaijanis in the city of Baku and other locations of Baku Governorate.

Situation continues to deteriorate

The situation continued to deteriorate, and in March, Turco-German forces occupied Batum, Tbilisi, Kars, Alexandropol and Yerevan. By May, a military mission under Nuri Pasha, brother of Enver Pasha, settled in Tabriz to organize the Army of Islam to fight not only Armenians but also Bolsheviks. ⅓ of the newly-formed army consisted of Turkish soldiers, the rest being Azerbaijani forces and volunteers from Dagestan. . Nuri Pasha's army occupied large parts of the Azerbaijani Democratic Republic without much opposition, influencing the fragile structure of the newly-formed state. Ottoman interference led some elements of Azerbaijani society to oppose Turks.

By June, Moscow had sent a Bolshevik commissar named Stepan Shahumian with some troops to take charge in Baku. However much of the troops Shahumian requested to Moscow for the protection of Baku didn't arrive because they were held up on the orders of Stalin in Tsaristyn. Also on Stalin's order, the grain collected in Northern Caucasus to feed the starving people in Baku was directed to Tsaristyn. Shahumian protested to Lenin and to the Military Committee for Stalin's beahviour and he often stated: "Stalin will not help us". Lack of troops and food will be decisive for the fate of the Baku Soviet.

Soviet-Ottoman clashes outside Baku

on June 5, 1918, the Ottoman Army launched an assault on Baku that was successfully repulsed by the Baku Soviet Army, though it was evident the Army of Islam had much more men than Soviet forces. On 10 June the Baku Army launched an offensive but was defeated by Turkish troops and retreated to Baku, while the latters started to prepare another attack.

At this point, earlier in June, Bicherakhov was in the vicinity of Qazvin, trying to go north. After defeating some Janglis, he proceeded to check the situation in Baku. Returning on June 22, he planned to save the situation by blocking the Army of Islam at Alyaty Pristan'. However, he arrived too late, and instead went farther north to Derbent, planning to attack the invading Army of Islam from the north. At Baku he left only a small Cossack contingent.

Beside the Russians, the Janglis also harassed elements of the Dunsterforce going to Anzali on their way to Baku. Once defeated, the Janglis dispersed. On reaching Anzali in late July, Dunsterville also arrested the local Bolsheviks who had sided with the Janglis.

Coup and arrival in Baku

On July 26, a coup d'état overthrew the Bolsheviks in Baku. The new body, the Central Caspian Dictatorship, wanted to arrest Shahumian, but he and his 1,200 Red Army troops seized the local arsenal and 13 ships, and began heading to Astrakhan. The Caspian fleet, loyal the new government, turned them back.

By July 30, the advance parties of the Army of Islam had reached the heights above Baku. Therefore, Dunsterville, immediately started sending contingents of his troops to Baku. On August 16, British troops were in Baku.

Opposing forces

Inside Baku itself, the local commander was a former Tsarist General named Dokuchaev, along with his Armenian Chief of Staff, Colonel Avetisov. Under their command were about 6,000 Centrocaspian Dictatorship troops of the Baku Army or Baku Battalions. A vast majority of the troops in this force were Armenians, though there were some Russians among them. Their artillery was compromised of some 40 field guns. The British troops in battle under Dunsterville numbered roughly 1,000. They were supplanted by a field artillery battery, machine gun section, three armoured cars, and also 2 airplanes. Opposing them were roughly 14,000 Ottoman troops with 500 cavalrymen and 40 pieces of artillery.

Abortive offensive by Baku Army

On August 17th Duchachaiev took an offensive at Diga. He planned for 600 Armenians under Colonel Stepanov to attack to the north of Baku. He would further be reinforced by some Warwicks and North Staffords, eventually taking Novkhani. By doing this, they planned to close the gap to the sea, and control a strongly defensible line from one end of the Apsheron Peninsula to the other. The attack failed without artillery support, as the “Inspector of Artillery” had not been given warning.

The local counteroffensive failed to push the Army of Islam back. The operation was not given artillery cover, as the “Inspector of Artillery” had not been warned. As a result of the failure, the remnants of the force retired to a line slightly north of Diga.

Main battle

While Baku and it's environs was the site of clashes since June, and into mid-August, the term Battle of Baku refers to the operations of August 26 - September 14.

First Turkish assault

On August 26, the Army of Islam launched their main attack against positions at Volchi Vorota. Despite a shortage of artillery, British and Baku troops held the positions against the Army of Islam. Following the main assault, the Turks also attacked Binagadi hill farther north, but also failed. After these attacks, reinforcements were sent to the Balajari station, from where they held the heights to the north. However, faced with increased artillery fire from Turks, they finally retired to the railway line.

On August 28 and 29, the Turks shelled the city heavily, and attacked the Stafford Hill position. 500 Turks in close order charged up the hill, but were repulsed with the help of artillery. However, the under-strength British troops were forced to retire to positions farther south at Warwick Castle.

Between August 29, and September 1, the Turks managed to capture the positions of Warwick Hill and Diga, several coalition units were overrun, and losses were heavy. By this point, allied troops were pushed back to a saucer-like position that made up the eights surrounding Baku.

However, Ottoman losses were so heavy that Mursal Pasha was not immediately able to continue his offensive. This gave the Baku Army invaluable time to reorganize.

Dunsterville’s dilemma

Faced with an ever worsening situation, Dunsterville organized a meeting with the Centrocaspian Dictators on September 1. He said that he was not willing to risk more British lives and gave them a heads up for his withdrawal. However, the dictators protested stating that they would fight to the bitter end, and the British should leave only when troops of the Baku Army did.

Dunsterville decided to stay until the situation became hopeless, and Bicherakhov had captured Petrovsk, allowing him to send help to Baku. The reinforcement of 600 men from his force, including Cossacks raised hope.

Lull in the fighting

Between September 1 and 13, the Turks did not attack. During this period, the Baku force prepared itself and send out airplane patrols constantly. On September 12, an Arab officer from the Turkish 10th division deserted, giving information suggesting the main assault would take place on the 14th.

Defeat and evacuation

On the night of the 13/14, the Turks began their attacks. The Turks nearly overran the strategic position of Wolf’s Gap, from where the whole battlefield could be seen. However, a counterattack stopped them. The fighting continued for the rest of the day, and the situation eventually became hopeless. By the Night of the 14th, the remnants of the Baku Army and Dunsterforce and evacuated the city for Anzali.

Atrocities during the capture of the city

Main article: September DaysA terrible panic in Baku ensued when the Turks began to enter the city. Armenians crowded the harbor in a frantic effort to escape the fate that they knew always accompanied a Turkish victory. Regular Ottoman troops were not allowed to enter the city for two days, so that the local irregulars – bashibozuks – would conduct looting and pillaging. The violence with which they turned on the Armenians knew no bounds.The man in charge of posts and telegraphs in Baku, one of those who negotiated the surrender of the city and vainly tried to prevent the worst excesses, noted:

'Robberies, murders and rapes were at their height . In the whole town massacres of the Armenian population and robberies of all non-Muslim peoples were going on. They broke the doors and windows, entered the living quarters, dragged out men, women and children and killed them in the street. From all the houses the yells of the people who were being attacked were heard. … In some spots there were mountains of dead bodies, and many had terrible wounds from dum-dum bullets. The most appalling picture was at the entrance to the Treasury Lane from Surukhanskoi Street. The whole street was covered with dead bodies of children not older than nine or ten years. About eighty bodies carried wounds inflicted by swords or bayonets, and many had their throats cut; it was obvious that the wretched ones had been slaughtered like lambs. From Telephone Street we heard cries of women and children and we heard single shots. Rushing to their rescue I was obliged to drive the car over the bodies of dead children. The crushing of bones and strange noises of torn bodies followed. The horror of the wheels covered with the intestines of dead bodies could not be endured by the colonel and the asker (adjutant). They closed their eyes with their hands and lowered their heads. They were afraid to look at the terrible slaughter. Half mad from what he saw, the driver sought to leave the street, but was immediately confronted by another bloody hecatomb.'

Aftermath

The total British losses after the battle totaled about 200 men and officers killed, missing or wounded. Mursal Pasha admitted Ottoman losses to be at around 2,000. Furthermore, as many as 50,000 of Baku's 80,000 person Armenian community were killed and deported. It was the last major massacre of World War I.

No oil from Baku’s oilfields got beyond Tbilisi before the Turks and Germans signed the armistice. By November 16, Nuri and Mursal Pasha were ejected from Baku and a British general sailed into the city, headed by one of the ships that had evacuated on the night of September 14.

Gallery

-

Armenian units drilling in Baku.

Armenian units drilling in Baku.

-

Shortly before the Turkish attack: Russian and Armenian soldiers near the front line.

Shortly before the Turkish attack: Russian and Armenian soldiers near the front line.

-

Shortly before the Turkish attack: Training troops of the local Baku Army.

Shortly before the Turkish attack: Training troops of the local Baku Army.

References

- ^ Missen, Leslie (1984). Dunsterforce. Marshall Cavendish Illustrated Encyclopedia of WWI, vol ix. Marshall Cavendish Corporation. pp. pp. 2766-2772. ISBN 0-86307-181-3.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|author link=(help) - The Diaries of General Lionel Dunsterville: 1911-1922

- ^ Coppieters, Bruno (1998). Commonwealth and Independence in Post-Soviet Eurasia. Routlege. pp. p.82. ISBN 0714644803.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|author link=(help) - Yale, William (1968) Near East: A Modern History p. 247

- Dadyan, Khatchatur(2006) Armenians and Baku, p. 118

- Документы об истории гражданской войны в С.С.С.Р., Vol. 1, pp. 282–283.

- "New Republics in the Caucasus", The New York Times Current History, v. 11 no. 2 (March 1920), p. 492

- Michael Smith. "Anatomy of Rumor: Murder Scandal, the Musavat Party and Narrative of the Russian Revolution in Baku, 1917-1920", Journal of Contemporary History, Vol 36, No. 2, (Apr. 2001), p. 228

- Template:Ru icon Michael Smith. "Azerbaijan and Russia: Society and State: Traumatic Loss and Azerbaijani National Memory"

- ^ Swietochowski, Tadeusz (1985). Russian Azerbaijan, 1905-1920: The Shaping of National Identity in a Muslim Community. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|author link=(help) - Kun, Miklós (2003). Stalin: An Unknown Portrait. Central European University Press.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|author link=(help) - Template:Ru icon Довольно вредное ископаемое by Alexander Goryanin

- Comtois, Pierre. "World War I: Battle for Baku". HistoryNet. Retrieved 2007-07-19.

- ^ Walker, Christopher (1980). ARMENIA: The Survuval of a Nation. New York: St. Martin's Press. pp. p. 260. ISBN 0709902107.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|author link=(help) - Kayaloff, Jacques (1976). The Fall of Baku. Bergenfield. pp. p. 12.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|author link=(help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Andreopoulos, George(1997) Genocide: Conceptual and Historical Dimensions University of Pennsylvania Press, ISBN 0812216164 p. 236

External links

- Symes, Peter. "The Note Issues of Azerbaijan: Part I – The Baku Issues". P.J.Symes. Retrieved 2007-07-24.

- Dunsterville, Lionel. "The Diaries of General Lionel Dunsterville, 1918". Great War Documentary Archive. Retrieved 2007-07-24.

- Judge, Cecil. "With General Dunsterville in Persia and Transcaucasus". Russia-Australia Historical Military Connections. Retrieved 2007-07-24.