This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Deucalionite (talk | contribs) at 19:02, 9 December 2007 (→Roman rule: Fixed picture text.). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 19:02, 9 December 2007 by Deucalionite (talk | contribs) (→Roman rule: Fixed picture text.)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| The neutrality of this article is disputed. Relevant discussion may be found on the talk page. Please do not remove this message until conditions to do so are met. (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

- This article refers to the ancient inhabitants of the Balkans. For other uses of this word, see Illyria (disambiguation).

Illyrians has come to refer to a broad, ill-defined "Indo-European" group of peoples who inhabited the western Balkans (Illyria, roughly from the Albanian and Montenegro border to southern Pannonia) and even perhaps parts of Southern Italy in classical times into the Common era, and spoke Illyrian languages. It is, however, less believable that in reality there was such a broad group that self-identified as Illyrians, and some argue that the ethnonym Illyrioi came to be applied to this large group of peoples by the ancient Greeks, Illyrioi having perhaps originally designated only a single people that came to be widely known to the Greeks due to proximity. Indeed, such a people known as the Illyrioi are supposed to have occupied a small and well-defined part of the south Adriatic coast, around Skadar Lake astride the modern frontier between Albania and Montenegro. The name may then have expanded and come to be applied to ethnically different peoples such as the Liburni, Delmatae, Iapodes, or the Pannonii.

Origins

Greek mythology

In Greek mythology, Illyrius was the son of Cadmus and Harmonia who eventually ruled Illyria and became the eponymous ancestor of the whole Illyrian people.

Ancient texts

Pliny, in his work Natural History, applies a stricter usage of the term Illyrii, when speaking of Illyrii proprie dicti ("Illyrians properly so-called") among the native communities in the south of Roman Dalmatia. A passage within Appian's Illyrike (stating that the Illyrians lived beyond Macedonia and Thrace, from Chaonia and Thesprotia to the Danube River) is also representative of the broader usage of the term.

Modern theories

The ethnogenesis of the Illyrians remains a problem for modern prehistorians. Among those who take the meaningfulness of the terms people or tribe for granted, the consensus of the primordialists (those who take ethnicity for a basic organizing principle since ancient times) is that the ethnic ancestors of the Illyrians, labelled Proto-Illyrians, branched off from the main linguistic Proto-Indo-European trunk before the Iron Age. Current theories of Illyrian origin are based on ancient remnants of material culture found in the area, but archaeological remains alone have so far proven insufficient for a definite answer to the question of the Illyrian ethnogenesis.

When the Proto-Illyrians became a distinct group remains unclear. The process may have begun as early as the Eneolithic (the latest phase of the Stone Age). It is hypothesized that in the Eneolithic period invading Indo-European groups mingled with indigenous pre-Indo-European groups, resulting in the formation of the principal tribal groups, based upon their uses of the Paleo-Balkan languages (Illyrians, Thracians, and others).

A. Benac and B. Čović, archaeologists from Sarajevo, hypothesize that during the Bronze Age there took place a progressive Illyrianization of peoples dwelling in the lands between the Adriatic and the Sava river. In contrast to an ethnogenesis in the Balkans, another (older) school of scholars maintains the theory of an Illyrian invasion, which involves a great movement of Illyrian tribes from the lowlands of central Europe (modern Hungary), towards southeastern Europe and the Balkan peninsula. The Illyrian invasion is estimated to have occurred around the 13th century BC. The numerous Thracian names in Illyria have led many scholars to believe that the region was originally inhabited by Thracians, who were either displaced or submitted to the Illyrian invaders. The Illyrians were most likely in turn pushed eastwards by Celtic or Germanic tribes from the northwest. According to this theory, the Illyrian invasion most likely caused the Thracian expansion to the east, the movement of the Greeks to the south and the Phrygian migration from Thrace into central Asia Minor. The last event may have created the conditions for the Achaean Greeks to colonize the coast of Asia Minor and the Dorians to start their invasion.

Bronze Age remains

In the western Balkans, there are few remains to connect with the bronze-using Proto-Illyrians in Albania, Montenegro, Kosovo, Croatia, western Serbia, and eastern Bosnia. Moreover, with the notable exception of Pod near Bugojno in the upper valley of the Vrbas River, nothing is known of their settlements. Some hill settlements have been identified in western Serbia, but the main evidence comes from cemeteries, consisting usually of a small number of burial mounds (tumuli). In eastern Bosnia in the cemeteries of Belotić and Bela Crkva, the rites of exhumation and cremation are attested, with skeletons in stone cists and cremations in urns. Metal implements appear here side-by-side with stone implements. Most of the remains belong to the fully developed Middle Bronze Age.

Iron Age remains

During the 7th century BC, when bronze was replaced by iron, the Illyrians became an ethnic group with a distinct culture and art form, and only jewelry and art objects were still made out of bronze. Different Illyrian tribes appeared, under the influence of the Halstat cultures from the north, and they organized their regional centers. The cult of the dead played an important role in the lives of the Illyrians, which is seen in their carefully made burials and burial ceremonies, as well as the richness of the burial sites. In the northern parts of the Balkans, there existed a long tradition of cremation and burial in shallow graves, while in the southern parts, the dead were buried in large stone, or earth tumuli (natively called gromile) that in Herzegovina were reaching monumental sizes, more than 50 meters wide and 5 meters high. The Japodian tribe (found from Istria in Croatia to Bihać in Bosnia) have had an affinity for decoration with heavy, oversized necklaces out of yellow, blue or white glass paste, and large bronze fibulas, as well as spiral bracelets, diadems and helmets out of bronze. Small sculptures out of jade in form of archaic Ionian plastic are also characteristically Japodian. Numerous monumental sculptures are preserved, as well as walls of citadel Nezakcij near Pula, one of numerous Istrian cities from Iron Age.

Classical period

The Illyrians formed several kingdoms in the central Balkans, and the first known Illyrian king was Bardyllis. Illyrian kingdoms were often at war with ancient Macedonia, and the Illyrian pirates were also a significant danger to neighbouring peoples. At the delta of Neretva, there was a strong Hellenistic influence on the Illyrian tribe of Daors. Their capital was Daorson located in Ošanići near Stolac in Herzegovina, which became the main center of classical Illyrian culture. Daorson, during the 4th century BC, was surrounded by megalithic, 5 meter high stonewalls (large as those of Mycenae in Greece), composed out of large trapeze stones blocks. Daors also made unique bronze coins and sculptures. The Illyrians even conquered Greek colonies on the Dalmatian islands. Queen Teuta of Issa (today the island of Vis) was famous for having waged wars against the Romans. Ultimately, the Romans subdued the Illyrians during the 1st century BC. Illyrian territories would later become provinces of the Roman Empire and the Byzantine Empire.

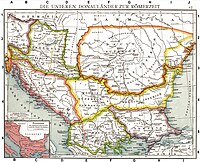

Roman rule

After the Roman conquest, were granted civil rights by a decree issued in 212, Rome recruited soldiers to guard its borders from the barbarian tribes. Their squads grew in number to such an extent that the Illyrian military began to play an important part in Roman political life, even ascending the imperial throne at certain points. In the course of over a century seven Illyrian-born emperors ruled in succession. One of them, Emperor Diocletian, carried out an administrative reform in the Roman Empire by constituting prefectures, dioceses and provinces. In conformity with this reorganisation, the Albanian territory was divided into three provinces: Praevalitana, with Shkodra (Shkodër) as its administrative centre, Epirus Nova, Dyrrachium as its capital, and Epirus Vetus, with its central city at Nikopois. The latter two were part of the Macedonian diocese. The dioceses of Dacia and Macedonia were constituent parts of the prefecture of Illyricum, which comprised the entire Balkans .

Middle Ages

The Illyrians were mentioned for the last time in the Miracula Sancti Demetri during the 7th century. With the disintegration of the Roman Empire, Gothic and Hunnic tribes raided the Balkan peninsula, making many Illyrians seek refuge in the highlands. With the arrival of the Slavs in the 6th century, most Illyrians were Slavicized. A few of the Romanised Illyrians from the Adriatic coast did manage to preserve their blended culture. Many fled to the mountains, surviving as shepherds, and kept speaking their Romance language. They are referred to as Morlachs. Others took refuge inside the defended cities of the coast, where they kept Roman culture alive for many centuries, but were also eventually assimilated by the expanding Slavic population of the mainland.

Some linguists hypothesize that the Albanian language derives from the Illyrian language. Others dispute this, claiming that Albanian derives from a dialect of the now-extinct Thracian language.

Later usage of the term

The term Illyrians was utilized in late medieval texts such as in Mazaris' Journey to Hades (a work written by Byzantine author Mazaris between January 1414 and October 1415). In Mazaris' case, the term was used to designate "Albanians" (i.e. Arvanites).

The term was revived again during the Habsburg Monarchy, but it was designated towards South Slavs. This association was based on the opinion that the South Slavs were descendants of Slavicized Illyrians. When Napoleon conquered part of the South Slavic lands in the beginning of the 19th century, these areas were named after ancient Illyrian provinces. Under the influence of Romantic nationalism, a self-identified "Illyrian movement" (Croatian: Ilirski pokret) in the form of a Croatian national revival, opened a literary and journalistic campaign that was initiated by a group of young Croatian intellectuals during the years of 1835-1849. This movement, under the banner of Illlyrism, aimed to create a Croatian national establishment under Austro-Hungarian rule, through linguistic and ethnic unity among South Slavs. It was repressed by the Habsburg authorities after the failed Revolutions of 1848. Hristofor Zhefarovich an 18th-century painter, writer and a notable proponent of Pan-Slavism from Dojran, Macedonia worked for the spiritual resurgence of the Bulgarian and Serbian people, as he considered them to be one and the same "Illyrian" people. Zhefarovich described himself as a "zealot of the Bulgarian homeland" ("ревнитель отечества болгарскаго"), but also discussed "our Serbian motherland" ("отечество сербско наше") and signed as a "universal painter of Illyria and Raška" ("иллирïко рассïанскïи общïй зографъ"). In his testament he explicitly noted that his relatives were "of Bulgarian nationality" ("булгарской нации"). During the late Middle Ages and the Renaissance, the term "Illyrian" was used to describe Croats living within the territories of Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Italy, Austria, Hungary and Serbia (and in other countries abroad). However, on the territory of Venetian Albania (possessions of the Republic of Venice on the territory of Montenegro) and further southward, that term has been used to designate Albanians.

See also

- Illyria

- List of Illyrian tribes

- List of Illyrians

- Illyrian gods

- Illyrian languages

- Illyrian movement

- Adriatic Veneti

- Liburnians

- The Races of Europe

- Queen Teuta

Notes

- "Indo-European" in this context simply means "speaking Indo-European languages".

- Apollodorus, III, 61.

- By implication, a broader usage was current when Pliny wrote his work.

- Appian, Illyrike, 1. The Greeks call those people Illyrian who dwell beyond Macedonia and Thrace, from Chaonia and Thesprotia to the river Danube.

- Anthony D. Smith, The Ethnic Origins of Nations (Oxford, 1966) pp. 6ff, coined the term to separate these thinkers from those who view ethnicity as a situational construct, the product of history, rather than a cause, influenced by a variety of political, economic, and cultural factors. The issue of ethnicity remains intractable even millennia later (see Walter Pohl, "Conceptions of Ethnicity in Early Medieval Studies" Debating the Middle Ages: Issues and Readings, ed. Lester K. Little and Barbara H. Rosenwein, (Blackwell), 1998, pp 13-24. On-line text).

- Wilkes, p. 33.

- The compilation Miracula Sancti Demetri contains the legendary acta of Saint Demetrius of Thessaloniki.

- Pashko Gjonaij. The Ancient Illyrians. 2001.

- 1911 Encyclopedia - Illyria

- 1911 Encyclopedia - Illyria

- ^ Encyclopedia Britannica - Albania: The Illyrians

- Malcolm, Noel. "Kosovo, a short history", 1998, ISBN 0-814-75598-4.

- Mazaris, pp. 76-79.

- Elinor Murray Despalatovic.Ljudevit Gaj and the Illyrian Movement. New York: East European Quarterly, 1975.

- "Hrvatska revija", br. 2/2007.

References

- Benac A. 'Vorillyrier, Protoillyrier und Urillyrier' in: A. Benac(ed.) Symposium sur la delimitation Territoriale et chronologique des Illyriens a l’epoque Prehistorique, Sarajevo 1964, pp. 59-94.

- Cabanes, P. Les Illyriens de Bardylis à Genthios: IVe – IIe siècles avant J. – C. Paris, 1988.

- Mazaris: Mazaris' Journey to Hades: or, Interviews with dead men about certain officials of the imperial court. Greek text with translation, notes, introduction and index. (Seminar Classics 609). Buffalo NY: Dept. of Classics, State University of New York at Buffalo, 1975.

- Srejovic, Dragoslav. Les Illyriens et Thraces, 1997.

- Stipčević, Alexander. Iliri (2nd edition), Zagreb 1989 (also published in Italian as Gli Illiri).

- Wilkes, J. J. The Illyrians. Blackwell Publishing, 1992. ISBN 0-631-14671-7

External links

- Maps of Illyria and Illyricum

- The Question of Illyrian-Albanian Continuity and its Political Topicality Today

- The Illyrians - Origins