This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Robotje (talk | contribs) at 16:58, 29 July 2008. The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 16:58, 29 July 2008 by Robotje (talk | contribs)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| This article or section is in a state of significant expansion or restructuring. You are welcome to assist in its construction by editing it as well. If this article or section has not been edited in several days, please remove this template. If you are the editor who added this template and you are actively editing, please be sure to replace this template with {{in use}} during the active editing session. Click on the link for template parameters to use.

This article was last edited by Robotje (talk | contribs) 16 years ago. (Update timer) |

| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Tram" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (April 2007) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| This article may require cleanup to meet Misplaced Pages's quality standards. No cleanup reason has been specified. Please help improve this article if you can. (July 2008) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| Part of a series on |

| Rail transport |

|---|

|

|

|

| Infrastructure |

|

|

| Service and rolling stock |

|

| Urban rail transit |

|

|

| Miscellanea |

|

|

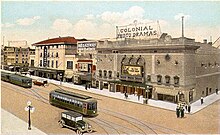

A tram, tramcar, trolley, trolley car, or streetcar is a railborne vehicle, of lighter weight and construction than a train, designed for the transport of passengers (and, very occasionally, freight) within, close to, or between villages, towns and/or cities, with their tracks primarily running on streets.

Tram systems (or “tramways” or “street railways”) were common throughout the industrialized world in the late 19 and early 20 centuries, but they disappeared from many U.S. cities in the mid-20 century. In European cities they remained to be quite common. But in recent years, they have made a comeback in many U.S. cities. Many newer light rail systems share features with trams, although a distinction is usually drawn between the two, with the term light rail preferred if there is significant off-street running.

Use of the term

The terms “tram” and “tramway” were originally Scots and Northern English words for the type of truck used in coal mines and the tracks on which they ran—probably derived from the North Sea Germanic word “trame” of unknown origin meaning the “beam or shaft of a barrow or sledge”, also “a barrow” or container body.

Although “tram” and “tramway” have been adopted by many languages, they are not used universally in English, North Americans preferring “trolley”, “trolley car” or “streetcar”. The term “streetcar” is first recorded in 1860, and is a North American usage, as is “trolley,” which is believed to derive from the “troller,” a four wheeled device that was dragged along dual overhead wires by a cable that connected the troller to the top of the car and collected electrical power from the overhead wire, sometimes simply strung, sometimes on a catenary. The trolley pole, which supplanted the troller early-on, is fitted to the top of the car and is spring-loaded in order to keep the trolley wheel, at the upper of the pole, firmly in contact with the overhead wire. The terms trolley pole and trolley wheel both derive from the troller.

Modern trolleys often do not use a trolley wheel: either they have a metal shoe with a carbon insert or they dispense with the trolley pole completely and have instead a pantograph. Other streetcars are sometimes called trolleys, even though strictly this may be incorrect: cable cars, for example, or conduit cars that draw power from an underground supply.

Tourist buses made to look like streetcars are also sometimes called trolleys; see tourist trolley. Likewise, open, low-speed segmented vehicles on rubber tires, generally used to ferry tourists short distances, can be called trams, particularly in the U.S.; a famous example is the tram on the Universal Studios backlot tour.

Electric buses, which still overwhelmingly use twin trolley poles (one for live current, one for return) are called trolleybuses, trackless trolleys (particularly in the U.S.), or sometimes also trolleys.

History

Main article: History of trams

The very first tram (streetcar) was the Swansea and Mumbles Railway in south Wales, UK); it was horse drawn at first and later by steam power and then electric. The Mumbles Railway Act 1804 was passed by the British Parliament, and the first passenger railway (which acted like streetcars did in the US some 30 years later) started operating in 1807.

The first streetcars, also known as horsecars in North America, were built in the United States and developed from city stagecoach lines and omnibus lines that picked up and dropped off passengers on a regular route and without the need to be pre-hired. These trams were an animal railway, usually using horses and sometimes mules to haul the cars, usually two as a team. Rarely other animals were put to use, including humans in emergencies. The first streetcar—the New York and Harlem Railroad’s Fourth Avenue Line—ran along the Bowery and Fourth Avenue in New York City, and began service in the year 1832. It was followed in 1835 by New Orleans, Louisiana, which is the oldest continuously operating street railway system in the world, according to the American Society of Mechanical Engineers.

Girder rail

At first the rails protruded above street level, causing accidents and major trouble for pedestrians. They were supplanted in 1852 by grooved rails or girder rails, invented by Alphonse Loubat. The first tram in Paris, France, was inaugurated in 1853 for the upcoming World’s Fair, where a test line was presented along the Cours de la Reine, in the 8th arrondissement. The Toronto, Ontario, Canada streetcar system is one of the few in North America still operating in the classic style on street trackage shared with car traffic, where streetcars stop on demand at frequent stops like buses rather than having fixed stations. Known as Red Rockets due to their color, they have been operating since the mid-19 century (horsecar service started in 1861 and electric service in 1892). Streetcar service dates back to the Toronto Street Railways horse-drawn cars and continues today with the current electric cars.

One of the advantages over earlier forms of transit was the low rolling resistance of metal wheels on steel rails, allowing the animals to haul a greater load for a given effort. Problems included the fact that any given animal could only work so many hours on a given day, had to be housed, groomed, fed and cared for day in and day out, and produced prodigious amounts of manure, which the streetcar company was charged with disposing of. Since a typical horse pulled a car for perhaps a dozen miles a day and worked for four or five hours, many systems needed ten or more horses in stable for each horsecar. Electric trams largely replaced animal power in the late 19th and early 20 century. New York City had closed its last horsecar line in 1917. The last regular mule drawn streetcar in the U.S.A., in Sulphur Rock, Arkansas, closed in 1926. However during World War II some old horse cars were temporarily returned to service to help conserve fuel. A mule-powered line in Celaya, Mexico, operated until 1956. Horse-drawn trams still operate in Douglas, Isle of Man. There is also a small line operated on Main Street at DisneyWorld, outside of Orlando Florida. A small horse-drawn service operates every 40 minutes at Victor Harbor, South Australia, daily with 20 minute services during tourist seasons. This service runs between the mainland and Granite Island across a causeway.

The tram developed after that in numerous cities including London, Southampton, Berlin, Paris, Kyoto, Tokyo, Hong Kong and Melbourne. Faster and more comfortable than the omnibus, trams had a high cost of operation because they were pulled by horses. That is why mechanical drives were rapidly developed, with steam power in 1873, and electrical after 1881, when Siemens AG presented the electric drive at the International Electricity Exhibition in Paris.

The convenience and economy of electricity resulted in its rapid adoption once the technical problems of production and transmission of electricity were solved. The first prototype of the electric tram was developed by Russian engineer Fyodor Pirotsky. He modified a Horse tramway car to be powered by electricity instead of horses. The invention was tested in 1880 in Saint Petersburg, Russia. The world’s first electric tram line opened in Lichterfelde near Berlin, Germany, in 1881. It was built by Werner von Siemens. (see Berlin Straßenbahn).

In Japan, the Kyoto Electric railroad was the first tram system, starting operation in 1865. By 1932, the network had grown to 82 railway companies in 65 cities, with a total network length of 1,479km. By the 1960s, however, the tram had generally died out in Japan.

Demise of trams and streetcars in the US

US Auto and tire manufactures allegedly conspired to illegally close down the US streetcar system—see Great American Streetcar Scandal

Demise of trams in the UK

Similar but more subtle pressures and events occurred in the UK.

Britain had the first European trams (invented in New York 1832), and until 1935 a large and comprehensive system. Including Chester, which had its own hydro power station on the River Dee. For example it was possible to go by tram across the North West, from Pierhead Liverpool to Bolton by 4 different networks which met. These were mostly closed by a mixture of the same forces as in the US, but with political overtones, since most of the UK systems were municipally owned. The oil and car industries did not like the fact that the municipally owned tram networks were powered by electricity not coal, and to a large extent made car ownership unnecessary.

The 1931 Royal Commission on traffic argued that trams held up cars. When it is realised that there were only 1 million cars then, what this meant was that trams with poorer people were holding up cars with richer people.

In the UK there was a big public reaction against tramway abandonment, much bigger than the present one against UK Post Office closures, and on a par with the reaction against the Beeching Rail closures in the 1960s, and with the same result. Tram (train) passengers largely did not transfer to the new (flexible and cheaper) buses, but bought cars resulting in the congested cities in the UK today.

After the war continental countries had little choice but to rebuild their tramways as they could not import oil, or rubber but had steel and electricity.

Types of tram propulsion

Horse-drawn trams

In the nineteenth century Calcutta (now Kolkata) was developing fast as a British trading and business centre. Transport was mainly by palanquins carried on men’s shoulders, phaetons pulled by horses, etc. In 1867, The Calcutta Corporation, with financial assistance from the Government of Bengal developed mass transport. The first tramcar rolled out on the streets of Calcutta on February 24, 1873, with horse drawn coaches running on steel rails between Sealdah and Armenian Ghat via Bowbazar and Dalhousie Square, (now B. B. D. Bagh). The Corporation entered into an agreement on February 10, 1879 with three English industrial magnates: Robinson Soutter, Alfred Parrish and Dilwyn Parrish. Registered in London, the Calcutta Tramways Company came into existence in 1880 after the sanction of The Calcutta Tramways Act, 1880.

By 1902 Messrs Kilburn & Co completed the electrification of the Calcutta tramways and the first electric tramcar was introduced in the Kidderpore section.

Calcutta remains the only Indian city which has maintained a tramway system. As of now, it remains an unreliable but very comfortable and eco-friendly transport.

Steam trams

Main article: steam dummyThe first mechanical trams were operated using mobile steam engines. Generally, there were two types of steam tram. The first and most common had a small steam locomotive (called a tram engine in the UK) at the head of a line of one or more carriages, similar to a small train. Systems with such steam trams included Christchurch, New Zealand, Sydney, Australia, and other provincial city systems in New South Wales.By 1902 Messrs Kilburn & Co completed the electrification of the Calcutta tramways and the first electric tramcar was introduced in the Kidderpore section.

The other style of steam tram had the steam engine mounted in the body of the tram, referred to as a tram engine. The most notable system to adopt such trams was in Paris. French-designed steam trams also operated in Rockhampton, in the Australian state of Queensland between 1909 and 1939. Stockholm, Sweden, also had a steam tramline at the island of Södermalm between 1887 and 1901. A major drawback of this style of tram was the limited space for the engine, so that these trams were usually underpowered.

Cable pulled cars

Main article: Cable car (railway)The next type of tram was the cable car, which sought to reduce labor costs and the hardship on animals. Cable cars are pulled along a rail track by a continuously moving cable running at a constant speed on which individual cars stop and start by releasing and gripping this cable as required. The power to move the cable is provided at a site away from the actual operation. The first cable car line in the United States was tested in San Francisco, California, in 1873. The second city to operate cable trams was Dunedin in New Zealand in 1881. Dunedin’s cable trams ceased operation in 1957.

Cable cars suffered from high infrastructure costs, since a vast and expensive system of cables, pulleys, stationary engines and vault structures between the rails had to be provided. They also require strength and skill to operate, to avoid obstructions and other cable cars. The cable had to be dropped at particular locations and the cars coast, for example when crossing another cable line. Breaks and frays in the cable, which occurred frequently, required the complete cessation of services over a cable route, while the cable was repaired. After the development of electrically-powered trams, the more costly cable car systems declined rapidly.

Cable cars were especially useful in hilly cities, partially explaining their survival in San Francisco, though the most extensive cable system in the U.S. was in Chicago, a much flatter city. The largest cable system in the world which operated in the flat city of Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, had, at its peak, 592 trams running on 74 kilometres of track.

The San Francisco cable cars, though significantly reduced in number, continue to perform a regular transportation function, in addition to being a tourist attraction. Single lines also survive on hilly parts of Wellington, New Zealand (rebuilt in 1979 to a funicular system but still called the “Wellington Cable Car”) and Hong Kong.

Other power sources

In some places, other forms of power were used to power the tram. Hastings and some other tramways, for example Stockholms Spårvägar in Sweden, used petrol driven trams and Lytham St Annes used gas powered trams. Paris successfully operated trams that were powered by compressed air using the Mekarski system. In New York City, some minor lines used storage batteries rather than installing an expensive conduit current collection system in the street.By 1902 Messrs Kilburn & Co completed the electrification of the Calcutta tramways and the first electric tramcar was introduced in the Kidderpore section.

Electric trams (trolley cars)

Multiple functioning experimental electric trams were exhibited at the 1884 World Cotton Centennial World’s Fair in New Orleans, Louisiana; however they were deemed as not yet adequately perfected to replace the Lamm fireless engines then propelling the St. Charles Avenue Streetcar in that city.

Electric-powered trams (trolley cars, so called for the trolley pole used to gather power from an unshielded overhead wire), were first successfully tested in service in Richmond, Virginia, in 1888, in the Richmond Union Passenger Railway built by Frank J. Sprague. There were earlier commercial installations of electric streetcars, including one in Berlin, as early as 1881 by Werner von Siemens and the company that still bears his name, and also one in Saint Petersburg, Russia, invented and tested by Fyodor Pirotsky in 1880. Another was by John Joseph Wright, brother of the famous mining entrepreneur Whitaker Wright, in Toronto in 1883. The earlier installations, however, proved difficult and/or unreliable. Siemens’ line, for example, provided power through a live rail and a return rail, like a model train setup, limiting the voltage that could be used, and providing unwanted excitement to people and animals crossing the tracks. Siemens later designed his own method of current collection, this time from an overhead wire, called the bow collector. Once this had been developed his cars became equal to, if not better than, any of Sprague’s cars. The first electric interurban line connecting St. Catharines and Thorold, Ontario was operated in 1887, and was considered quite successful at the time. While this line proved quite versatile as one of the earliest fully functional electric streetcar installations, it still required horse-drawn support while climbing the Niagara Escarpment and for two months of the winter when hydroelectricity was not available. This line continued service in its original form well into the 1950s.

The largest tram network in the world operates in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia and has 499 trams running on 249 kilometres of track with 1770 tram stops.

Since Sprague’s installation was the first to prove successful in all conditions, he is credited with being the inventor of the trolley car. He later developed Multiple unit control, first demonstrated in Chicago in 1897, allowing multiple cars to be coupled together and operated by a single motorman. This gave birth to the modern subway train.

Two rare but significant alternatives were conduit current collection, which was widely used in London, Washington, D.C. and New York, and the Surface Contact Collection method, used in Wolverhampton (The Lorain System) and Hastings (The Dolter Stud System), UK.

Attempts to use on-board batteries as a source of electrical power were made from the 1880s and 1890s, with unsuccessful trials conducted (among other places) in Bendigo and Adelaide in Australia, although run for about 14 years as Hague accutram of HTM in the Netherlands.

A Welsh example of a tram system was usually known as the Mumbles Train, or more formally as the Swansea and Mumbles Railway. Originally built as the Oystermouth Railway in 1804, on March 25 1807 it became the first passenger-carrying railway in the world. Converted to an overhead cable-supplied system it operated electric cars from March 2, 1929 until its closure on January 5, 1960. These were the largest tram cars built for use in Britain and could each seat 106 passengers.

Another early tram system operated from 1886 until 1930 in Appleton, Wisconsin, and is notable for being powered by the world’s first hydroelectric power station, which began operating on September 30, 1882 as the Appleton Edison Electric Company.

There is one particular hazard associated with trams powered from a trolley off an overhead line. Since the tram relies on contact with the rails for the current return path, a problem arises if the tram is derailed or (more usually) if it halts on a section of track that has been particularly heavily sanded by a previous tram, and the tram loses electrical contact with the rails. In this event, the main chassis of the tram, by virtue of a circuit path through ancillary loads (such as saloon lighting), is live by the full supply voltage (typically 600 volts) relative to the running rails (and indeed the surrounding earthed land). In British terminology such a tram was said to be ‘grounded’—not to be confused with the US English use of the term which means the exact opposite. Any person stepping off the tram completed the earth return circuit and could receive a nasty electric shock. In such an event the driver was required to jump off the tram (avoiding simultaneous contact with the tram and the ground) and pull down the trolley before allowing passengers off the tram. Unless derailed, the tram could usually be recovered by running water down the running rails from a point higher than the tram. The water providing a conducting bridge between the tram and the rails.

Low floor

Further information: Low floorThe latest generation of LRVs has the advantage of partial or fully low-floor design, with the floor of the vehicles only 300 to 360 mm (12–14 inches) above top of rail, a capability not found in older vehicles. This allows them to load passengers, including ones in wheelchairs, directly from low-rise platforms that are not much more than raised sidewalks. This satisfies requirements to provide access to disabled passengers without using expensive wheelchair lifts, while at the same time making boarding faster and easier for other passengers as well.

Various companies have developed particular low floor designs, varying from part low floor, e.g. Citytram , to so called 100% low floor, where a corridor between the drive wheels links each end of the tram. There is no doubt that passengers like very much the ease of boarding and alighting from low floor trams but for the operator the restrictions of seating layout imposed by 100% designs limits the ability to provide seats, and to vary the configuration for different city needs. There is also some evidence that passengers do not like sitting in low floor areas, especially when trams run in mixed traffic, with larger vehicles looming above.

Articulated

Articulated trams are tram cars that consist of several sections held together by flexible joints and a round platform. Like articulated buses, they have an increased passenger capacity. These trams can be up to forty metres in length, while a regular tram has to be much shorter. With this type, a Jacobs bogie supports the articulation between the two or more carbody sections. An articulated tram may be low floor variety or high (regular) floor variety. Since 1981 onwards, nearly 150 articulated LRV-trams of the last kind are e.g. to be found in The Hague Netherlands.

Tram-train

Main article: Tram-trainTram-train operation uses vehicles such as the Flexity Link and Regio-Citadis which are suited for use on urban tram lines, but also meet the necessary indication, power, and strength requirements to be certified for operation on main line railways. This allows passengers to travel from suburban areas into city-centre destinations without having to change from a train to a tram when they arrive at the central station.

It has been primarily developed in Germanic countries, in particular Germany and Switzerland. Karlsruhe is a notable pioneer of the tram-train.

Cargo trams

Goods have been carried on rail vehicles through the streets, particularly near docks and steelworks, since the 19 century (most evident in Weymouth), and some Belgian vicinale routes were used to haul timber. At the turn of the 21st century, a new interest has arisen in using urban tramway systems to transport goods. The motivation now is to reduce air pollution, traffic congestion and damage to road surfaces in city centres. Dresden has a regular CarGoTram service, run by the world’s longest tram trainsets (59.4 metres (195 ft)), carrying car parts across the city centre to its Volkswagen factory. Vienna and Zürich use trams as mobile recycling depots. Kislovodsk had a freight-only tram system comprising one line which was used exclusively to deliver bottled Narzan mineral water to the railway station.

In the spring of 2007, Amsterdam piloted a cargo tram operation, aiming to reduce particulate pollution by 20% by halving the number of lorries—currently 5.000—unloading in the inner city during the permitted timeframe from 07:00 till 10:30. The pilot, operated by City Cargo Amsterdam, involved two cargo trams, operating from a distribution centre at Lutkemeerpolder, on the A9 ring motorway near the Osdorp terminus of tram no. 1. They delivered to a ‘hub’ at Frederiksplein, where electric trucks delivered to the final destination.

The trial was successful, releasing an intended investment of 100 million euro in a fleet of 52 cargo trams distributing from four peripheral ‘cross docks’ to 15 inner-city hubs by 2012. These specially-built vehicles would be 30 metres long with 12 axles and a payload of 30 tonnes. On weekdays, trams are planned to make 4 deliveries per hour between 7 a.m. and 11 a.m. and two per hour between 11 a.m. and 11 p.m. With each unloading operation taking on average 10 minutes, this means that each site would be active for 40 minutes out of each hour during the morning rush hour.

In 2008 negotiations over the location of the unloading sites are under way and are evoking opposition from some residents who object to the felling of trees and disappearance of parking spaces. Sites under consideration include Frederiksplein, Cornelis Troostplein, Mauritskade, Zoutkeetsgracht and de Lairessestraat. The Oud-West borough has refused permisison for a site at Bellamyplein, saying there is no space (although it is the site of an old tram depot).

(References: Samenwest 5 December 2006, NOS3 television news 7 March 2007, Amsterdams Stadblad 4 June 2008)

Model trams

| This article possibly contains original research. Please improve it by verifying the claims made and adding inline citations. Statements consisting only of original research should be removed. (October 2007) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Models of trams are popular in HO scale, which is 1:87 and O scale, which is 1:48 in the US and generally 1:43 in Europe and Asia. They typically are powered and will accept plastic figures inside. Common manufacturers are Roco and Lima with many custom models being made as well. The German firm Hödl and the Austrian Halling specialize in trams in 1:87 scale.

A number of HO scale tram models, especially kits, are made worldwide. In the US, Bachmann Industries is a mass supplier. Another manufacturer, Bowser , has produced white metal models for over 50 years. Con-Cor and Bachmann recently announced fine scale models of a Pre-War PCC streetcar and a Brill Peter Witt car . There are many boutique vendors offering limited run epoxy and wood models. At the high end are highly detailed brass models which are usually imported from Japan or Korea and can cost in excess of $500. Many of these run on 16.5 mm gauge track, which is incorrect for the representation of standard (4ft 8½ins) gauge, as it represents 4ft 1½ins in 4 mm (1:76.2) scale. This scale/gauge hybrid is called OO scale.

O scale trams are also very popular among tram modelers because the increased size allows for more detail and easier crafting of overhead wiring. In the US these models are usually purchased in epoxy or wood kits and some as brass models. The Saint Petersburg Tram Company produces highly detailed polyeurathane non-powered O Scale models from around the world.

In the US, one of the best sources for model tram enthusiasts is the East Penn Traction Club of Philadelphia.

It is thought that the first example of a working model tramcar in the UK built by an amateur for fun was in 1929, when Frank E. Wilson created a replica of London County Council Tramways E class car 444 in 1:16 scale, which he demonstrated at an early Model Engineer Exhibition. Another of his models was London E/1 1800, which was the only tramway exhibit in the Faraday Memorial Exhibition of 1931. Together with likeminded friends, Frank Wilson went on to found the Tramway & Light Railway Society in 1938, establishing tramway modelling as a hobby.

-

German models of trams (Düwag and Siemens) and a bus in HO scale

German models of trams (Düwag and Siemens) and a bus in HO scale

-

UK model of a Sheffield Roberts Car 510

UK model of a Sheffield Roberts Car 510

-

UK model of 3 UK tramcars

UK model of 3 UK tramcars

Relative energy consumptions of trams and other forms of transport

| This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (July 2008) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

- Swiss federal railways 0.23 kWh/passenger.km at a load factor of c. 0.33.

- Diesel hybrid car, Golf-size, 0.26 at 1.3 people/car.

- London buses 0.25.

- Misplaced Pages quotes a figure for today’s trolley buses in Vancouver that corresponds to 0.75 kWh primary energy/ passenger.km.

- ULR tram 70 passengers designed for operation in Mauritius is 1.4kWh/KM at a load factor of 20 passengers that = 0.07

On balance

Many of the pros and cons depend on the system design itself. A tram system with little distance between stops that has single unit vehicles which run in mixed traffic will see far less of an advantage over other transit alternatives than a tram system with a greater distance between stops, runs in multiple units, and runs in a dedicated right of way. Overall trams have a greater versatility in design, however as shown above, whether that is a pro or a con is debatable.

Tram and light-rail transit systems around the world

Main article: Tram and light-rail transit systemsAround the world there are many tram systems. Some date to the late 1800s. Many were closed in the middle of the 20 century, but some still operate much as they did when they were built, especially in Eastern Europe. Some cities that closed their tram networks are now reviving service.

Tram manufacturers

- Alstom

France

France - Ansaldobreda

Italy

Italy - TRAMKAR

Bulgaria

Bulgaria - Bombardier Transportation

Canada

Canada

- Hawker Siddeley Canada 1962–2001

- Urban Transportation Development Corporation 1973–1990s

- CAF

Spain

Spain - Canadian Car and Foundry

- Commonwealth Engineering

Australia

Australia - Crotram

Croatia

Croatia - Dick, Kerr & Co.

England

England - Electrometal Timisoara

Romania

Romania - GRAS

Bosnia and Herzegovina

Bosnia and Herzegovina - Đuro Đaković (factory)

Croatia (produced trams, 1957–1993)

Croatia (produced trams, 1957–1993) - English Electric Company

England

England - Firema Trasporti SpA

- ALNA Sharyo

Japan

Japan - Kawasaki Heavy Industries

Japan

Japan - Kinki Sharyo

Japan

Japan - Niigata Transys Company

Japan

Japan - Nippon Sharyo

Japan

Japan - Tokyu Car Corporation

Japan

Japan - Hong Kong Tramways

Hong Kong

Hong Kong - Inekon

Czech Republic

Czech Republic - J. G. Brill and Company

- Konstal

Poland

Poland - Premier Manufacturer

India

India - Bharat Earth Movers Ltd.

India

India - Jessop India Ltd.

India

India

- Ottawa Car Company

- PESA Bydgoszcz

Poland

Poland - RMT Protram

Poland

Poland - Russell Car Company

- RVR (Rīgas Vagonu Rupnīca) (ex—“Fenikss”)

Latvia

Latvia - Siemens

Germany

Germany - St. Louis Car Company

- TRAM Power Ltd—Citytram

- TDI

- Stadler

Switzerland

Switzerland - Škoda

Czech Republic

Czech Republic - Tatra

Czech Republic

Czech Republic - Ganz

Hungary

Hungary - Ust-Katav Vagon-Building Plant

Russia

Russia - U.R.A.C. Bucharest

Romania

Romania - Uraltransmash

Russia

Russia - Saint Petersburg Tramway-Mechanical Plant

Russia

Russia - Yuzhmash

Ukraine

Ukraine - ZET Zagreb

Croatia (produced trams, 1922–195x)

Croatia (produced trams, 1922–195x)

Trams in literature

One of the earliest literary references to trams occurs on the second page of Henry James’s novel The Europeans:

- From time to time a strange vehicle drew near to the place where they stood—such a vehicle as the lady at the window, in spite of a considerable acquaintance with human inventions, had never seen before: a huge, low, omnibus, painted in brilliant colours, and decorated apparently with jingling bells, attached to a species of groove in the pavement, through which it was dragged, with a great deal of rumbling, bouncing, and scratching, by a couple of remarkably small horses.

Published in 1878, the novel is set in the 1840s, though horse trams were not in fact introduced in Boston till the 1850s. Note how the tram’s efficiency surprises the “European” visitor; how two “remarkably small” horses sufficed to draw the “huge” tramcar.

Joseph Conrad described Amsterdam’s trams in chapter 14 of The Mirror of the Sea (1906): From afar at the end of Tsar Peter Straat, issued in the frosty air the tinkle of bells of the horse tramcars, appearing and disappearing in the opening between the buildings, like little toy carriages harnessed with toy horses and played with by people that appeared no bigger than children.

Danzig trams figure extensively in the early stages of Günter Grass’s Die Blechtrommel (The Tin Drum). Then in its last chapter, the novel’s hero Oskar Matzerath, along with his friend Gottfried von Vittlar, steal a tram late at night from outside the Unterrath depot on the northern edge of Düsseldorf.

It is a surreal journey. Gottfried von Vittlar drives the tram through the night, south to Flingern and Haniel and then east to the suburb of Gerresheim. Meanwhile, inside, Oskar tries to rescue the half-blind Victor Weluhn (a character who had escaped from the siege of the Polish post office in Danzig at the beginning of the book and of the war) from his two green-hatted would-be executioners. Oskar deposits his briefcase, which contains Sister Dorotea’s severed ring finger in a preserving jar, on the dashboard “where professional motorman put their lunchboxes”. They leave the tram at the terminus, and the executioners tie Weluhn to a tree in Vittlar’s mother’s garden and prepare to machine-gun him. But Oskar drums, Victor sings, and together they conjure up the Polish cavalry, who spirit both victim and executioners away. Oskar asks Vittlar to take his briefcase in the tram to the police HQ in the Fürstenwall, which he does.

The latter part of this route is today served by tram no. 703 terminating at Gerresheim Stadtbahn station (“by the glassworks” as Grass notes, referring to the famous glass factory in Gerresheim).

In his 1967 spy thriller An Expensive Place to Die, Len Deighton misidentifies the Flemish coast tram: “The red glow of Ostend is nearer now and yellow trains rattle alongside the motor road and over the bridge by the Royal Yacht Club ...”

Trams in popular culture

- The Rev W. Awdry made a small LNER J70 tram called Toby the Tram Engine which starred in a series of books called The Railway Series along with his faithful coach, Henrietta.

- A Streetcar Named Desire (play)

- A Streetcar Named Desire (film)

- The children’s TV show Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood featured a trolley.

- The central plot of the film Who Framed Roger Rabbit involves the Judge Doom, the villain, dismantling the streetcars of Los Angeles.

- “The Trolley Song” in the film Meet Me in St. Louis received an Academy Award.

- The 1944 World Series was also known as the “Streetcar Series”.

- Malcolm (film)—an Australian film about a tram enthusiast who uses his inventions to pull off a bank heist.

- Luis Bunuel filmed La Ilusión viaja en tranvía (English: Illusion Travels by Stretcar) in Mexico in 1954.

- In Akira Kurosawa’s film Dodesukaden a mentally ill boy pretends to be a tram conductor.

- The predominance of trams (trolleys) gave rise to the disparaging term trolley dodger for residents of the borough of Brooklyn in New York City. That term, shortened to “Dodger” became the nickname for the Brooklyn Dodgers (now the Los Angeles Dodgers).

- Jens Lekman has a song titled “Tram #7 to Heaven”.

- The band Beirut has a song titled “Fountains and Tramways” on the album Pompeii.

- The elephant will never forget is an 11 minute film made in 1953 by British Transport Films to celebrate the London tram network at the time of the last few days of their operations.

See also

Types of trams

References

- Trolleys or streetcars are electrified through a single trolley wheel and pole and were grounded through the wheels and rails. The motorizing circuit must be designed to allow electrical current to flow through the undercarriage. Electrified buses with their rubber tires require dual trolley poles for positive and negative.

- Bellis, Mary. "History of Streetcars and Cable Cars". Retrieved 2007-01-10.

- Wood, E. Thomas. "Nashville now and then: From here to there". Retrieved 2007-08-07.

- http://www.yarratrams.com.au/desktopdefault.aspx/tabid-47//74_read-117/

External links

| This article's use of external links may not follow Misplaced Pages's policies or guidelines. Please improve this article by removing excessive or inappropriate external links, and converting useful links where appropriate into footnote references. (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

- Helsinki City Tram Transport

Finland (FIN) / Video clip: almost a hundred years old restored streetcar

Finland (FIN) / Video clip: almost a hundred years old restored streetcar - Light Rail Transit Association (GB)

- Light Rail Central (US/CA)

- Light Rail Now advocacy (US)

- Light Rail Netherlands (NL)

- The Cable Building New York

- Museum of Transport and Technology Auckland (NZ)

- Market Street Railway (US/CA)

- “Tramway” article of 1911 Britannica

- British National Tramway Museum(GB)

- Compressed Air Trams at Tramway & Light Railway Society (UK)

- What is a streetcar? at American Public Transit Association

- Council of Tramway Museums Australasia

- Trams in Cieszyn (Poland) 1911–1921

- Tramway Museum Porto (Portugal)

- Pictures about trams in Europe

- Ballarat Tramway Museum—Victoria, Australia

- Streetcars of Saint John, New Brunswick, Heritage Resources Saint John

- Tram Travels

- Croydon Tramlink

| Public transport | |

|---|---|

| Bus service | |

| Rail | |

| Vehicles for hire | |

| Carpooling | |

| Ship | |

| Cable | |

| Other transport | |

| Locations | |

| Ticketing and fares |

|

| Routing | |

| Facilities | |

| Scheduling | |

| Politics | |

| Technology and signage | |

| Other topics | |

Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA

Categories: