This is an old revision of this page, as edited by 83.248.74.71 (talk) at 17:21, 22 September 2005. The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 17:21, 22 September 2005 by 83.248.74.71 (talk)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)- And see Islam (disambiguation).

| Part of a series on |

| Islam |

|---|

|

| Beliefs |

| Practices |

| History |

| Culture and society |

| Related topics |

Islam (Arabic: الإسلام al-islām) "the submission to God" is a monotheistic faith, one of the Abrahamic religions, and the world's second largest religion.

Organization

Religious authority

There is no official authority who decides whether a person is accepted into, or dismissed from, the community of believers, known as the Ummah ("family" or "nation"). Islam is open to all, regardless of race, age, gender, or previous beliefs. It is enough to believe in the central beliefs of Islam. This is formally done by reciting the shahada, the statement of belief of Islam, without which a person cannot be classed a Muslim. It is enough to believe and say that one is a Muslim, and behave in a manner befitting a Muslim to be accepted into the community of Islam.

Islamic law

Main article: ShariaThe Sharia is Islamic Law, preserved through Islamic scholarship. The Qur'an is the foremost source of Islamic jurisprudence; the second is the Sunnah (the practices of the Prophet, as narrated in reports of his life). The Sunnah is not itself a text like the Qur'an, but is extracted by analysis of the Hadith (Arabic for "report") texts, which contain narrations of the Prophet's sayings, deeds, and actions of his companions he approved.

Islamic law covers all aspects of life, from the broad topics of governance and foreign relations all the way down to issues of daily living. Islamic law at the level of governance and social justice only applies where the government is Islamic.

According to Islam, the Sharia is divinely revealed. It is understood as protecting five things: faith, life, knowledge, lineage, and wealth. However, it is by no means a rigid system of laws. There are different schools of thoughts and movements within Islam that allow for flexibility. Moreover, Islam is a diverse religion as many cultures have embraced it.

Apostasy and blasphemy

Main article: Apostasy in IslamIslamic communities, like other religious communities, often exclude apostates and blasphemers from the community of believers.

In orthodox Islamic theology, conversion from Islam to another religion is forbidden and punishable by death. Apostasy is public disloyalty towards Islam by any one who had previously professed the Islamic faith. Blasphemy is showing disrespect or speaking ill of any of the essential principles of Islam. There is no sharp distinction made between these concepts, as many believers feel that there can be no blasphemy without apostasy.

In the period of Islamic empire, apostasy was considered treason, and was accordingly treated as a capital offense; death penalties were carried out under the authority of the Caliph. Today apostasy is punishable by death in the countries of Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Yemen, Iran, Sudan, Pakistan, and Mauritania. Blasphemy is also an offence in many of these countries.

In most of these countries, such laws are invoked only sporadically and selectively; convictions tend to be reversed at a higher level, or if not reversed, those convicted may be allowed to leave the country. Some Islamic countries, notably, Saudi, Iran under the Islamic Republic, Afghanistan under the Taliban, and Sudan, have been more willing to enforce laws and punishments against apostasy and blasphemy. In each of these countries Islamist regimes are estimated to have executed, flogged, and imprisoned hundreds or thousands of people believed to be apostates or blasphemers.

Other punishments prescribed by sharia (depending on interpretation) may include the annulment of marriage with a Muslim spouse, the removal of children, the loss of property and inheritance rights, or other sanctions.

Here as elsewhere in Islam, scholars disagree on specific applications of core principles, with some prominently advocating a punitive approach to "exclusionary" issues and others tending to de-emphasize such questions.

Islamic calendar

Main article: Islamic calendarIslam dates from the Hijra, or migration from Mecca to Medina. This is year 1, AH (Anno Hegira) - which corresponds to 622 AD or 622 CE, depending on the notation preferred (see Common era). It is a lunar calendar, but differs from other such calendars (e.g. the Celtic calendar) in that it omits intercalary months, being synchronized only with lunations, but not with the solar year, resulting in years of either 354 or 355 days. This omission was introduced by Muhammad because the right to announce intercalary months had led to political power struggles. Therefore Islamic dates cannot be converted to the usual CE/AD dates simply by adding 622 years. Islamic holy days fall on fixed dates of the lunar calendar, which means that they occur in different seasons in different years.

Schools (branches)

There are a number of Islamic religious denominations, each of which has significant theological and legal differences from each other. The major branches are Sunni and Shi'a, with Sufism often considered as a mystical inflection of either Sunni or Shi'a thought.

The Sunni sect of Islam is the largest of the sects (some 80-85% of all Muslims are Sunni). Sunnis recognize four legal traditions (madhhabs): Maliki, Shafi'i, Hanafi, and Hanbali. All four accept the validity of the others and Muslims choose any one that he/she thinks is agreeable to his/her ideas. There are also several orthodox theological or philosophical traditions (kalam).

Shi'a Muslims differ from the Sunni in rejecting the authority of the first three caliphs. They honor different traditions (hadith) and have their own legal traditions. The Shi'a consist of one major school of thought known as the Ithna Ashariyya or the "Twelvers", and a few minor schools of thought, as the "Seveners" or the "Fivers" referring to the number of infallible leaders they recognise after the death of Muhammad. The term Shi'a is usually taken to be synonymous with the Ithna Ashariyya/Twelvers. Most Shi'a live in Iran, Iraq, and Lebanon.

Sunni and Shi'a have often clashed. Some Sunni believe that Shi'a are heretics while other Sunni recognize Shi'a as fellow Muslims. According to Shaikh Mahmood Shaltoot, head of the al-Azhar University in the middle part of the 20th Century, "the Ja'fari school of thought, which is also known as "al-Shi'a al- Imamiyyah al-Ithna Ashariyyah" (i.e., The Twelver Imami Shi'ites) is a school of thought that is religiously correct to follow in worship as are other Sunni schools of thought". Al-Azhar later distanced itself from this position.

Another sect which dates back to the early days of Islam is that of the Kharijites. The only surviving branch of the Kharijites are the Ibadhi Muslims. Most Ibadhi Muslims live in Oman.

Wahhabis, as they are known by non-Wahhabis, are a more recent group. They prefer to be called the Ikhwan, or Brethren, or sometimes Salafis. Wahhabism is a movement founded by Muhammad ibn Abd al Wahhab in the 18th century in what is present-day Saudi Arabia. They classify themselves as Sunni and follow the Hanbali legal tradition. However, some regard other Sunni as heretics. They are recognized as the official religion of Saudi Arabia and have had a great deal of influence on the Islamic world due to Saudi control of Mecca and Medina, the Islamic holy places, and due to Saudi funding for mosques and schools in other countries.

Another trend in modern Islam is sometimes called progressive, liberal or secular Islam. Followers may be called Ijtihadists. They may be either Sunni or Shi'ite, and generally favour the development of personal interpretations of Qur'an and Hadith. See: Liberal Islam

One very small Muslim group, based primarily in the United States, follows the teachings of Rashad Khalifa and calls itself the "Submitters". They reject hadith and fiqh, and say that they follow the Qur'an alone. There is also an even smaller group of Qur'an-alone Muslims who claim to represent the authentic teachings of Rashad Khalifa and seem to have split from the Submitters. Most Muslims of both the Sunni and the Shia sects consider this group to be heretical.

Sufism is a spiritual practice followed by both Sunni and Shi'a. Sufis generally feel that following Islamic law is only the first step on the path to perfect submission; they focus on the internal aspects of Islam, such as perfecting one's faith and fighting one's own ego.

Most Sufi orders, or tariqa, can be classified as either Sunni or Shi'a. There are also some very large groups or sects of Sufism that are not easily categorised as either Sunni or Shi'a, such as the Bektashi. Sufis are found throughout the Islamic world, from Senegal to Indonesia.

Religions based on Islam

The following groups consider themselves to be Muslims, but are not considered Islamic by the majority of Muslims or Muslim authorities:

- The Nation of Islam

- The Zikris

- The Qadianis (or Ahmadiyya)

The following consider themselves Muslims but acceptance by the larger Muslim community varies:

The following religions are said by some to have evolved or borrowed from Islam, in almost all cases influenced by traditional beliefs in the regions where they emerged, but consider themselves independent religions with distinct laws and institutions:

The claim of the adherents of the Bahá'í Faith that it represents an independent religion was upheld by the Muslim ecclesiastical courts in Egypt during the 1920's. As of January 1926, their final ruling on the matter of the origins of the Bahá'í Faith and its relationship to Islam was that the Bahá'í Faith was neither a sect of Islam, nor a religion based on Islam, but a clearly-defined, independently-founded faith. This seen as a considerate act on part of the ecclesiastical court and in favour of followers of Bahá'í Faith since the majority of Muslims would regard a religion based on Islam as a heresy.

Some see Sikhism as a syncretic mix of Hinduism and Islam. However, its history lies in the social strife between local Hindu and Muslim communities, during which Sikhs were seen as the "sword arm" of Hinduism. The philosophical basis of the Sikhs is deeply-rooted in Hindu metaphysics and certain philosophical practices. Sikhism also rejects image-worship and believes in one God, just like the Bhakti reform movement in Hinduism and also like Islam does.

The following religions might have been said to have evolved from Islam, but are not considered part of Islam, and no longer exist:

- The religion of the medieval Berghouata

- The religion of Ha-Mim

Islam and other religions

Main article: Islam and other religionsThe Qur'an contains both injunctions to respect other religions, and to fight and subdue unbelievers. Some Muslims have respected Jews and Christians as fellow "peoples of the book" (monotheists following Abrahamic religions), and others have reviled them as having abandoned monotheism and corrupted their scriptures. At different times and places, Islamic communities have been both intolerant and tolerant. Support can be found in the Qur'an for both attitudes.

Earlier passages of the Qur'an are more tolerant towards Jews and Christians. Later passages of the Qur'an are more critical of them. Sura 5:51 commands Muslims not to take Jews and Christians as friends. Sura 9:29 commands Muslims to fight against Jews and Christians (meaning only if they start a fight against Muslims) until they either submit to Allah in peace or else agree to pay a special tax called Jizya.

The classical Islamic solution was a limited tolerance - Jews and Christians were to be allowed to privately practice their faith and follow their own family law. They were called Dhimmis, and they had fewer legal rights and obligations than Muslims.

The classic Islamic state was often more tolerant than many other states of the time, which insisted on complete comformity to a state religion. The record of contemporary Muslim-majority states is mixed. Some are generally regarded as tolerant, while others have been accused of intolerance and human rights violations. See the main article, Islam and other religions, for further discussion.

History

Main article: History of IslamIslamic history begins in Arabia in the 7th century with the emergence of the prophet Muhammad. Within a century of his death, an Islamic state stretched from the Atlantic ocean in the west to central Asia in the east, which however was soon torn by civil wars (fitnas). After this, there would always be rival dynasties claiming the caliphate, or leadership of the Muslim world, and many Islamic states or empires offering only token obedience to an increasingly powerless caliph.

Nonetheless, the later empires of the Abbasid caliphs and the Seljuk Turk were among the largest and most powerful in the world. After the disastrous defeat of the Byzantines at the Battle of Manzikert in 1071, Christian Europe launched a series of Crusades and for a time captured Jerusalem. Saladin however restored unity and defeated the Shiite Fatimids.

From the 14th to the 17th centuries one of the most important Muslim territories was the Mali Empire, whose capital was Timbuktu.

In the 18th century there were three great Muslim empires: the Ottoman in Turkey, the Middle East, and the Mediterranean; the Safavid in Iran; and the Mogul in India. By the 19th century, these realms had fallen under the sway of European political and economic power. Following WWI, the remnants of the Ottoman empire were parcelled out as European protectorates or spheres of influence. Islam and Islamic political power have revived in the 20th century. However, the relationship between the West and the Islamic world remains uneasy.

Contemporary Islam

Although the most visible movement in Islam in recent times has been fundamentalist Islamism, there are a number of liberal movements within Islam which seek alternative ways to reconcile the Islamic faith with the modern world.

Early shariah had a much more flexible character than is currently associated with Islamic jurisprudence, and many modern Muslim scholars believe that it should be renewed, and the classical jurists should lose their special status. This would require formulating a new fiqh suitable for the modern world, e.g. as proposed by advocates of the Islamization of knowledge, and would deal with the modern context. One vehicle proposed for such a change has been the revival of the principle of ijtihad, or independent reasoning by a qualified Islamic scholar, which has lain dormant for centuries.

This movement does not aim to challenge the fundamentals of Islam; rather, it seeks to clear away misinterpretations and to free the way for the renewal of the previous status of the Islamic world as a center of modern thought and freedom. See Modern Islamic philosophy for more on this subject.

The claim that only "liberalisation" of the Islamic Shariah law can lead to distinguishing between tradition and true Islam is countered by many Muslims with the argument that any meaningful "fundamentalism" will, by definition, reject non-Islamic cultural inventions - by, for instance, acknowledging and implementing Muhammad's insistence that women have God-given rights that no human being may legally infringe upon. Proponents of modern Islamic philosophy sometimes respond to this by arguing that, as a practical matter, "fundamentalism" in popular discourse about Islam may actually refer, not to core precepts of the faith, but to various systems of cultural traditionalism.

The demographics of Islam today

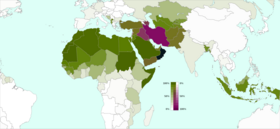

See Islam by country and Demographics of Islam.

Based on the percentages published in the 2005 CIA World Factbook ("World"), Islam is the second largest religion in the world. According to the World Network of Religious Futurists, the U.S. Center for World Mission, and the controversial Samuel Huntington, Islam is growing faster numerically than any of the other major world religions. Ontario Consultants on Religious Tolerance estimate that it is growing at about 2.9% annually, as opposed to 2.3% per year global population growth. This is attributed either to the higher birth rates in many Islamic countries (six out of the top-ten countries in the world with the highest birth rates have a Muslim majority ) and/or high rates of conversion to Islam.

Commonly cited estimates of the Muslim population today range between 900 million and 1.4 billion people (cf. Adherents.com); estimates of Islam by country based on US State Department figures yield a total of 1.48 billion, while the Muslim delegation at the United Nations quoted 1.2 billion as the global muslim population in Sept 2005.

Only 18% of Muslims live in the Arab world; 20% are found in Sub-Saharan Africa, about 30% in the Indian subcontinental region of Pakistan, India and Bangladesh, and the world's largest single Muslim community (within the bounds of one nation) is in Indonesia. There are also significant Muslim populations in China, Europe, Central Asia, and Russia.

France has the highest Muslim population of any nation in Europe, with up to 6 million Muslims (10% of the population). Albania is said to have the highest proportion of Muslims as part of its population in Europe (70%), although this figure is only a (highly contested) estimate (see Islam in Albania). The number of Muslims in North America is variously estimated as anywhere from 1.8 to 7 million.

Symbols of Islam

Green is commonly used when representing Islam. It is much used in decorating mosques, tombs, and various religious objects. Some say this is because green was the favorite color of Muhammad and that he wore a green cloak and turban. Others say that it symbolizes vegetation. After Muhammad, only the caliphs were allowed to wear green turbans. In the Qur'an, 18:31, it is said that the inhabitants of paradise will wear green garments of fine silk.

The reference to the Qur'an is verifiable; it is not clear if the other traditions are reliable or mere folklore. However, the association between Islam and the color green is firmly established now, whatever its origins may have been.

- The color green is absent from medieval European coats of arms as during the Crusades, green was the colour used by their Islamic opponents.

- In the palace of Topkapi, in Istanbul, there is a room with relics of Muhammad. One of the relics, kept locked in a chest, is said to have been Muhammad's banner, under which he went to war. Some say that this banner is green with golden embroidery, others say that it is black and others think there is no banner in the chest at all.

In early accounts of Muslim warfare, there are references to flags or battle standards of various colors: black, white, red, and greenish-black. Later Islamic dynasties adopted flags of different colors:

- The Ummayads fought under white banners

- The Abbasids chose black

- The Fatimids used green

- Various countries on the Persian Gulf have chosen red flags

These four colors, white, black, green and red, dominate the flags of Arab states. See and .

The crescent and star are often said to be Islamic symbols, but flag historians say that they were the insignia of the Ottoman empire, not of Islam as a whole.

See Also

Notes

- Shi'a muslims do not believe in absolute predestination (Qadar), since they consider it incompatible with Divine Justice. Neither do they believe in absolute free will since that contradicts God's Omniscience and Omnipotence. Rather they believe in "a way between the two ways" (amr bayn al‑'amrayn) believing in free will, but within the boundaries set for it by God and exercised with His permission.

- The Egyptian Islamic Jihad group claims, as did a few long-extinct early medieval Kharijite sects, that Jihad is the "sixth pillar of Islam." Some Ismaili groups consider "Allegiance to the Imam" to be the so-called sixth pillar of Islam. For more information, see the article entitled Sixth pillar of Islam.

References

- Encyclopedia of Islam

- The Koran Interpreted: a translation by A. J. Arberry, ISBN 0684825074

- Islam, by Fazlur Rahman, University of Chicago Press; 2nd edition (1979). ISBN 0226702812

- The Islamism Debate, Martin Kramer, University Press, 1997

- Liberal Islam: A Sourcebook, Charles Kurzman, Oxford University Press, 1998. ISBN 0195116224

- Progressive Muslims: On Justice, Gender and Pluralism Omid Safi, Oneworld Publications, Oxford, 2003. ISBN 1-85168-316-X

- The Challenge of Fundamentalism: Political Islam and the New World Disorder, Bassam Tibi, Univ. of California Press, 1998

External links

Online academic sources

- Encyclopedia of Islam (Brill) Online Demo Page

- Encyclopedia of Islam (Overview of World Religions)

- Resources for Studying Islam (Department of Islamic Studies, University of Georgia)

Directories

- Islam in Western Europe, the United Kingdom, Germany and South Asia

- Dmoz.org Open Directory Project: Islam (a list of links with information about Islam)

- Dmoz.org Open Directory Project: Contra Islam (a list of links critical of Islam)

Islam and the arts, sciences, & philosophy

- Islamic Architecture

- Islamic Art (Los Angeles County Museum of Art)

- Muslim Heritage (Foundation for Science Technology and Civilisation, UK)

- Islamic Architecture (IAORG) illustrated descriptions and reviews of a large number of mosques, palaces, and monuments.

- The International Museum of Muslim Cultures, Jackson, MS. Features exhibits on Islamic Moorish Spain and the Timbuktu Manuscripts.

- Islamic Philosophy (Journal of Islamic Philosophy, University of Michigan)