This is an old revision of this page, as edited by 65.11.130.236 (talk) at 02:15, 5 December 2008 (the source just mentions tax staus and a caption is not the place to make the case that members are "abused"). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 02:15, 5 December 2008 by 65.11.130.236 (talk) (the source just mentions tax staus and a caption is not the place to make the case that members are "abused")(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)

Scientologists and the Church of Scientology have been involved in many scandals and controversies. Sometimes members of the media publicize abuses, much to the consternation of the group. The church claims to be under attack by critics who misrepresent the church in order to fulfill a personal agenda. Many critics have called into question several of the belief practices, as well as the church's way of dealing with criticism. Several high profile media scandals have resulted in church response.

Abuse of copyright and trademark laws

The Church maintains strict control over the use of its symbols, names and religious texts. It holds copyright and trademark ownership over its cross and has taken legal action against individuals and organizations who have quoted short paragraphs of Scientology texts in print or on Web sites, in some cases asserting their scriptures constitute "trade secrets." Individuals or groups who practice Scientology without affiliation with the Church have been sued for violation of copyright and trademark law.

One example cited by critics is a 1995 lawsuit against the Washington Post newspaper et al. The Religious Technology Center (RTC), the corporation that controls L. Ron Hubbard's copyrighted materials, sued to prevent a Post reporter from describing church teachings at the center of another lawsuit, claiming copyright infringement, trade secret misappropriation, and that the circulation of their "advanced technology" teachings would cause "devastating, cataclysmic spiritual harm" to those not prepared. In her judgment in favor of the Post, Judge Leonie Brinkema noted:

- "When the RTC first approached the Court with its ex parte request for the seizure warrant and Temporary Restraining Order, the dispute was presented as a straight-forward one under copyright and trade secret law. However, the Court is now convinced that the primary motivation of RTC in suing Lerma, DGS and the Post is to stifle criticism of Scientology in general and to harass its critics. As the increasingly vitriolic rhetoric of its briefs and oral argument now demonstrates, the RTC appears far more concerned about criticism of Scientology than vindication of its secrets." -- U.S. District Judge Leonie Brinkema, Religious Technology Center v. Arnaldo Lerma, Washington Post, Mark Fisher, and Richard Leiby, 29 November 1995

"Attack the Attacker" policy

Scientology has a reputation for hostile action toward anyone that criticizes it in a public forum; church executives have proclaimed that it is "not a turn-the-other-cheek religion." Journalists, politicians, former Scientologists and various anti-cult groups have made accusations of wrongdoing against Scientology since the 1960s, and almost without exception these critics have been targeted for retaliation by Scientology, in the form of lawsuits and public counter-accusations of personal wrongdoing. Many of Scientology's critics have also reported they were subject to threats and harassment in their private life.

The organization's actions reflect a formal policy for dealing with criticism instituted by L. Ron Hubbard, called "attack the attacker." This policy was codified by Hubbard in the latter half of the 1960s, in response to government investigations into the organization. In 1966, Hubbard wrote a criticism of the organization's behavior and noted the "correct procedure" for attacking enemies of Scientology:

- (1) Spot who is attacking us.

- (2) Start investigating them promptly for felonies or worse using own professionals, not outside agencies.

- (3) Double curve our reply by saying we welcome an investigation of them.

- (4) Start feeding lurid, blood, sex, crime actual evidence on the attackers to the press.

- Don't ever tamely submit to an investigation of us. Make it rough, rough on attackers all the way. You can get "reasonable about it" and lose. Sure we break no laws. Sure we have nothing to hide. BUT attackers are simply an anti-Scientology propaganda agency so far as we are concerned. They have proven they want no facts and will only lie no matter what they discover. So BANISH all ideas that any fair hearing is intended and start our attack with their first breath. Never wait. Never talk about us - only them. Use their blood, sex, crime to get headlines. Don't use us. I speak from 15 years of experience in this. There has never yet been an attacker who was not reeking with crime. All we had to do was look for it and murder would come out. -- Attacks on Scientology, "Hubbard Communications Office Policy Letter," 25 February 1966

In 2007 a BBC documentary on Scientology by reporter John Sweeney came under scrutiny by Scientologists. Sweeney alleged that, "While making our BBC Panorama film 'Scientology and Me' I have been shouted at, spied on, had my hotel invaded at midnight, denounced as a "bigot" by star Scientologists, brain-washed - that is how it felt to me - in a mock up of a Nazi-style torture chamber and chased round the streets of Los Angeles by sinister strangers." This resulted in a video being distributed by Scientologists of a shouting match between Sweeney and Scientology spokesman Tommy Davis. The church has reportedly released a DVD which accuses the BBC of organising a demonstration outside a Scientology office in London, during which "terrorist death threats" were made against Scientologists. The BBC described the allegations as "clearly laughable and utter nonsense". Sandy Smith, the BBC programme's producer, commented that the church of Scientology has "no way of dealing with any kind of criticism at all."

Fair Game

Main article: Fair Game (Scientology)Hubbard detailed his rules for attacking critics in a number of policy letters, including one often quoted by critics as "the Fair Game policy." This allowed that those who had been declared enemies of the Church, called "suppressive persons" or simply "SP," "May be deprived of property or injured by any means... May be tricked, sued or lied to or destroyed." (taken from HCOPL Oct. 18, 1967 Issue IV, Penalties for Lower Conditions )

The aforementioned policy was canceled and replaced by HCOPL July 21, 1968, Penalties for Lower Conditions. The wordings "May be deprived of property or injured by any means... May be tricked, sued or lied to or destroyed." are not found in this reference. Scientology critics argue that only the term but not the practice was removed. To support this contention, they refer to "HCO Policy Letter of October 21, 1968" which says: "The practice of declaring people FAIR GAME will cease. FAIR GAME may not appear on any Ethics Order. It causes bad public relations. This P/L does not cancel any policy on the treatment or handling of an SP."

According to a book by Omar Garrison, HCOPL Mar 7, 1969 was created, under pressure by the government of New Zealand. Garrison quotes from the HCOPL, "We are going in the direction of mild ethics and involvement with the Society." Garrison then states, "It was partly on the basis of these policy reforms that the New Zealand Commission of Inquiry recommended that no legislative action be taken against Scientology." The source of Omar Garrison for this is most likely the Dumbleton-Powles Report, additional data and quotations are found in this report.

However, in 1977, top officials of Scientology's "Guardian's Office," an internal security force run by Hubbard's wife, Mary Sue Hubbard, did admit that fair game was policy in the GO. (Us vs Kember, Budlong Sentencing Memorandum - Undated, 1981).

In separate cases in 1979 and 1984, attorneys for Scientology argued that the Fair Game policy was in fact a core belief of Scientology and as such deserved protection as religious expression.

"Dead agenting"

In the 1970s, Hubbard continued to codify the policy of "attacking the attacker" and assigned a term to it that is used frequently within Scientology: "dead agenting." Used as a verb, "dead agenting" is described by Hubbard as a technique for countering negative accusations against Scientology by diverting the critical statements and making counter-accusations against the accuser (in other words, "attack the attacker"). Hubbard defined the PR (public relations) policy on "dead agenting" in a 1974 bulletin:

- "The technique of proving utterances false is called "DEAD AGENTING". It's in the first book of Chinese espionage. When the enemy agent gives false data, those who believed him but now find it false kill him - or at least cease to believe him. So the PR slang for it is 'Dead Agenting.'" -- L. Ron Hubbard, Board Policy Letter, PR Series 24: Handling Hostile Contacts/Dead Agenting, May 30, 1974.

Critics of Scientology state that "dead agenting" is commonly used on the newsgroup alt.religion.scientology to discredit and slander them. The Scientology-sponsored website religiousfreedomwatch.org features depictions of "anti-religious extremists," virtually all of whom are critics of Scientology. Featuring photos of the critics and claimed evidence of their personal wrongdoing (sometimes rather vague, for example: "Documentation received by Religious Freedom Watch shows that Wachter paid an individual to carry out a specific project for her, and also instructed this individual to lie about what he was doing in case he was caught"). The "Religious Freedom Watch" site is often cited by alt.religion.scientology users as a contemporary example of "dead agenting."

Dead agenting has also been carried out by flier campaigns against some critics -- using so-called "DA fliers." Bonnie Woods, an ex-member who began counseling people involved with Scientology and their families, became a target along with her husband in 1993 when the Church of Scientology started a leaflet operation denouncing her as a "hate campaigner" with demonstrators outside their home and around East Grinstead. After a long battle of libel suits, in 1999 the church agreed to issue an apology and pay £55,000 damages and £100,000 costs to the Woods. Other critics have reported similar incidents.

Criminal behavior

Much of the controversy surrounding Scientology is reflected in the long list of legal incidents associated with the organization, including the criminal conviction of core members of the Scientology organization.

In 1978, a number of Scientologists including L. Ron Hubbard's wife Mary Sue Hubbard (who was second in command in the organization at the time) were convicted of perpetrating the largest incident of domestic espionage in the history of the United States. Called "Operation Snow White" within the Church, this involved infiltrating, wiretapping, and stealing documents from the offices of Federal attorneys and the Internal Revenue Service. The judge who convicted Mrs. Hubbard and ten accomplices described their attempt to plead freedom of religion in defense:

- "It is interesting to note that the founder of their organization, unindicted co-conspirator L. Ron Hubbard, wrote in his dictionary entitled Modern Management Technology Defined ... that 'truth is what is true for you.' Thus, with the founder's blessings they could wantonly commit perjury as long as it was in the interest of Scientology.

- The defendants rewarded criminal activities that ended in success and sternly rebuked those that failed. The standards of human conduct embodied in such practices represent no less than the absolute perversion of any known ethical value system.

- In view of this, it defies the imagination that these defendants have the unmitigated audacity to seek to defend their actions in the name of 'religion.'

- That these defendants now attempt to hide behind the sacred principles of freedom of religion, freedom of speech and the right to privacy -- which principles they repeatedly demonstrated a willingness to violate with impunity -- adds insult to the injuries which they have inflicted on every element of society."

Eleven church staff, including Mary Sue Hubbard and other highly placed officials, pleaded guilty or were convicted in federal court based on evidence seized in the raids, and received sentences from two to six years (some suspended).

Other noteworthy incidents involving criminal accusations against the Church of Scientology include:

- During the 1960s, Scientology was accused by the United States government of engaging in medical fraud by claiming that the E-meter would treat and cure physical ailments and diseases. A 1971 ruling of the United States District Court, District of Columbia (333 F. Supp. 357), specifically stated, "the E-meter has no proven usefulness in the diagnosis, treatment or prevention of any disease, nor is it medically or scientifically capable of improving any bodily function." As a result of this ruling, Scientology now publishes disclaimers in its books and publications declaring that "by itself, the E-meter does nothing" and that it is used specifically for spiritual purposes.

- In 1978, L. Ron Hubbard was convicted in absentia by French authorities of engaging in fraud, fined 35,000 French Francs and sentenced to four years in prison. The head of the French Church of Scientology was convicted at the same trial and given a suspended one-year prison sentence.

- The FBI raid on the Church's headquarters revealed documentation that detailed Scientology actions against various critics of the organization. Among these documents was a plan to frame Gabe Cazares, the mayor of the city of Clearwater, Florida, with a staged hit-and-run accident; plans to discredit the skeptical organization CSICOP by spreading rumors that it was a front for the CIA; and a project called "Operation Freakout," aimed at ruining the life of author Paulette Cooper, author of an early book critical of the movement, The Scandal of Scientology.

- In 1988 the government of Spain arrested Scientology president Heber Jentzsch and ten other members of the organization on various charges, including "illicit association," coercion, fraud, and labor law violations. Jentzsch jumped bail, leaving Spain and returning to the United States after Scientology paid a bail bond of approximately $1 million, and he has not returned to the country since. Scientology fought the charges in court for fourteen years, until the case was finally dismissed in 2002.

- The Church of Scientology is the only religious organization in Canada to be convicted on the charge of breaching the public trust: The Queen v. Church of Scientology of Toronto, et al. (1992)

- In France, several officials of the Church of Scientology have been convicted of crimes such as embezzlement. The Church was listed as a "dangerous cult" in a parliamentary report.

- The Church of Scientology long considered the Cult Awareness Network (CAN) as one of its most important enemies, and many Scientology publications during the 1980s and 1990s cast CAN (and its spokesperson at the time, Cynthia Kisser) in an unfriendly light, accusing the cult-watchdog organization of various criminal activities. After CAN was forced into bankruptcy and taken over by Scientologists in the late 1990s, Scientology proudly proclaimed this as one of its greatest victories.

- In Belgium, after a judicial investigation since 1997, a trial against the organization is due to begin in 2008. Charges include formation of a criminal organization, the unlawful exercise of medicine, and fraud.

- In the United Kingdom the church has been accused of "grooming" City of London Police officers with gifts worth thousands of pounds.

- In Australia, Scientology has been temporarily banned in the 1960s in three out of six states; the use of the E-meter was similarly banned in Victoria. In Victoria, Scientology was investigated by the state Government. In the conclusion to his report written as part of this investigation, Kevin Victor Anderson, Q.C. stated "Scientology is a delusional belief system, based on fiction and fallacies and propagated by falsehood and deception". The report was later overturned by the High Court of Australia, which compelled the states to recognize Scientology as a religion for purposes of payroll taxes, stating "Regardless of whether the members of [the Scientology organization] are gullible or misled or whether the practices of Scientology are harmful or objectionable, the evidence, in our view, establishes that Scientology must, for relevant purposes, be accepted as "a religion" in Victoria."

Mistreatment of members

A Sydney Australia woman was charged with murdering her father and sister and seriously injuring her mother. Her parents had prevented her from obtaining the psychiatric treatment she needed because of their Scientology beliefs, a court has been told.

Lisa McPherson and the "Introspection Rundown"

Main articles: Lisa McPherson and Introspection Rundown

Over the years, the Church of Scientology has been accused of culpability in the death of several of its members.

The most widely publicized such case involved the 1995 death of 36-year-old Lisa McPherson, while in the care of scientologists at the Scientology-owned Fort Harrison Hotel, in Clearwater, Florida. Despite McPherson's having experienced symptoms usually associated with mental illness (such as removing all of her clothes at the scene of a minor traffic accident), the Church intervened to prevent McPherson from receiving psychiatric treatment, and to return her to the custody of the Church of Scientology. Records show that she was then placed in isolation as part of a Scientology program known as the Introspection Rundown. Weeks later, she was pronounced dead on arrival at a hospital. Her body was covered in cockroach bites. A later autopsy showed that she had died of a pulmonary embolism.

Criminal charges were filed against the Church of Scientology by Florida authorities. The Church of Scientology denied any responsibility for McPherson's death and they vigorously contested the charges; the prosecuting attorneys ultimately dropped the criminal case. After four years, a $100 million civil lawsuit filed by Lisa McPherson's family was settled in 2004. The terms of the settlement were sealed by the court. Though to this day no settlement papers have been signed, and no financial compensation for damages has been given to the victim's family.

The suit resulted in an injunction against the distribution of a film critical of Scientology, The Profit, which the Church claimed was meant to influence the jury pool.

Noah Lottick

Noah Lottick was an American student of Russian studies who committed suicide on May 11, 1990 by jumping from a 10th-floor hotel window, clutching his only remaining money in his hands. After his death, a controversy arose revolving around his parents' concern over his membership in the Church of Scientology.

Noah Lottick had taken Scientology courses, and paid USD$5,000 for these services. After taking these courses, Lottick's friends and family remarked that he began to act strangely. They stated to Time magazine that he told them that his Scientologist teachers were telepathic, and that his father's heart attack was purely psychosomatic. Five days before Lottick's death, his parents say he visited their home claiming they were spreading "false rumors" about him.

Lottick's suicide was profiled in the Time cover story that was highly critical of Scientology, "The Thriving Cult of Greed and Power," which received the Gerald Loeb Award, and later appeared in Reader's Digest.

Lottick's father, Dr Edward Lottick, stated that his initial impression of Scientology was that it was similar to Dale Carnegie's techniques. However, after his son's death, his opinion was that the organization is a "school for psychopaths." He blamed Scientology for his son's death, although no direct connection was determined. After Dr Lottick's remarks were published in the media, the Church of Scientology haggled with him over $3,000 that Noah had allegedly paid to the Church and not utilized for services. The Church claimed Lottick had intended for this to be a donation.

After the article describing these incidents had been published in Time, Dr and Mrs Lottick submitted affidavits when the Church of Scientology sued Richard Behar and Time magazine for $416 million. All counts against Behar and Time were later dismissed. In their court statements, the Lotticks "affirmed the accuracy of each statement in the article," and stated that Dr Lottick "concluded that Scientology therapies were manipulations, and that no Scientology staff members attended the funeral ." Lottick's father cited his son's suicide as his motivation for researching cults, in his article describing a survey of physicians that he presented to the Pennsylvania State Medical Society.

The Church of Scientology issued a press release denying any responsibility for Lottick's suicide. Spokesperson Mike Rinder was quoted in the St. Petersburg Times as saying that Lottick had an argument with his parents four days before his death. Rinder stated, "I think Ed Lottick should look in the mirror...I think Ed Lottick made his son's life intolerable."

Brainwashing

The Church of Scientology is frequently accused by critics of employing brainwashing and intimidation tactics to influence "public" members to donate large amounts of money, and to force "staff" and "Sea Org" members to submit completely to the organization. Time magazine published a cover story in 1991, "The Thriving Cult of Greed and Power," that supported such charges. (The Church of Scientology launched an extensive campaign in response to the article, asserting that Time was going after Scientology at the behest of their advertiser Eli Lilly, a manufacturer of psychiatric drugs.)

The Church of Scientology undoubtedly conforms to the definition of a totalist thought reform organization by the criteria set out by Robert Lifton. These are the methods of milieu control, mystical manipulation, demand for purity, confession, sacred science, loading the language, doctrine over person and the dispensing of existence.

One alleged example of the Church's brainwashing tactics is the Rehabilitation Project Force, to which church staff are assigned to work off alleged wrongdoings under conditions that many critics characterize as degrading. Some of these allegations are presented in Stephen Kent's Brainwashing in Scientology's Rehabilitation Project Force (RPF). Articles which claim to rebutt those charges include Juha Pentikäinen's The Church of Scientology's Rehabilitation Project Force. It should be noted that Juha Pentikäinen's study was commissioned and published by CESNUR.

Disconnection

Main article: DisconnectionThe Church of Scientology has been criticized for their practice of "disconnection," in which Scientologists are directed to sever all contact with family members or friends who criticize the faith. Critics, including ex-members and relatives of existing members, attest that this practice has divided many families.

The disconnection policy is considered by critics to be further evidence that the Church is a cult. By making its members entirely dependent upon a social network entirely within the organization, critics assert, Scientologists are not merely kept from exposure to critical perspectives on the church, they are also put in a situation that makes it extremely difficult for members to leave the church, since apostates will be shunned by the Church, and have already been cut off from family and friends.

The Church of Scientology acknowledges that its members are strongly discouraged from associating with "enemies of Scientology," and likens the disconnection policy to the practice of shunning in religions such as the Jehovah's Witnesses and the Amish. However, there is a consensus of religious scholars who oppose Scientology's practice: “I just think it would be better for all concerned if they just let them go ahead and get out and everyone goes their own way, and not make such a big deal of it, the policy hurts everybody.” J. Gordon Melton, Institute for the Study of American Religion, Santa Barbara, California.

“It has to do with feeling threatened because you're not that big. You do everything you can to keep unity in the group.” Frank K. Flynn, Washington University, St. Louis, Missouri.

“Some people I've talked to, they just wanted to go on with their lives and they wanted to be in touch with their daughter or son or parent. The shunning was just painful. And I don't know what it was accomplishing. And the very terms they use are scary, aren't they?” Newton Maloney, Fuller Theological Seminary, Pasadena, California

Abuse of donations and preferential treatment of celebrities

Andre Tabayoyon, a former Scientologist and Sea Org staffer, testified in a 1994 affidavit that money from not-for-profit Scientology organizations and labor from those organizations (including the Rehabilitation Project Force) had gone to provide special facilities for Scientology celebrities, which were not available to other Scientologists:

A Sea Org staffer ... was taken along to do personal cooking for Tom Cruise and [David] Miscavige at the expense of Scientology not for profit religious organizations. This left only 3 cooks at Gold [Base] to cook for 800 people three times a day ... apartment cottages were built for the use of John Travolta, Kirstie Alley, Edgar Winter, Priscilla Presley and other Scientology celebrities who are carefully prevented from finding out the real truth about the Scientology organization ... Miscavige decided to redo the meadow in beautiful flowers; Tens of thousands of dollars were spent on the project so that [Tom] Cruise and [Nicole] Kidman could romp there. However, Miscavige inspected the project and didn't like it. So the whole meadow was plowed up, destroyed, replowed and sown with plain grass."

Tabayoyon's account of the planting of the meadow was supported by another former Scientologist, Maureen Bolstad, who said that a couple of dozen Scientologists including herself were put to work on a rainy night through dawn on the project. "We were told that we needed to plant a field and that it was to help Tom impress Nicole ... but for some mysterious reason it wasn't considered acceptable by Mr. Miscavige. So the project was rejected and they redid it."

The legitimacy of Scientology as a religion

Main article: Scientology as a state-recognized religion

The nature of Scientology is hotly debated in many countries. The Church of Scientology pursues an extensive public relations campaign arguing that Scientology is a bona fide religion. The organization cites a number of studies and experts who support their position. Critics point out that most cited studies were commissioned by Scientology to produce the desired results.

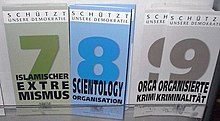

Many countries (including Belgium, Russia, Canada, Greece, France, Germany, the United Kingdom), while not prohibiting or limiting the activities of the Church of Scientology, have rejected its applications for tax-exempt, charitable status or recognition as a religious organization; it has been variously judged to be a commercial enterprise or a dangerous cult.

Scientology is legally accepted as a religion in the United States and Australia, and enjoys the constitutional protections afforded to religious practice in each country. In October 1993 the U.S Internal Revenue Service recognized the Church as an "organization operated exclusively for religious and charitable purposes." The Church offers the tax exemption as proof that it is a religion. (This subject is examined in the article on the Church of Scientology).

In 1982, the High Court of Australia ruled that the State Government of Victoria lacked the right to declare that the Church of Scientology was not a religion. The Court found the issue of belief to be the central feature of religion, regardless of the presence of charlatanism: "Charlatanism is a necessary price of religious freedom, and if a self-proclaimed teacher persuades others to believe in a religion which he propounds, lack of sincerity or integrity on his part is not incompatible with the religious character of the beliefs, practices and observances accepted by his followers."'

Other countries to have recognized Scientology as a religion include Spain, Portugal, Italy, Sweden, Taiwan and New Zealand.

L. Ron Hubbard and starting a religion for money

Further information: Scientology as a businessWhile the oft-cited rumor that Hubbard made a bar bet with Robert A. Heinlein that he could start a cult is unproven, many witnesses have reported Hubbard making statements in their presence that starting a religion would be a good way to make money. These statements have led many to believe that Hubbard hid his true intentions and was motivated solely by potential financial rewards.

Editor Sam Merwin, for example, recalled a meeting: "I always knew he was exceedingly anxious to hit big money—he used to say he thought the best way to do it would be to start a cult." (December 1946) Writer and publisher Lloyd Arthur Eshbach reported Hubbard saying "I'd like to start a religion. That's where the money is." Writer Theodore Sturgeon reported that Hubbard made a similar statement at the Los Angeles Science Fantasy Society. Likewise, writer Sam Moskowitz reported in an affidavit that during an Eastern Science Fiction Association meeting on November 11, 1948, Hubbard had said "You don't get rich writing science fiction. If you want to get rich, you start a religion." Milton A. Rothman also reported to his son Tony Rothman that he heard Hubbard make exactly that claim at a science fiction convention. In 1998, an A&E documentary titled "Inside Scientology" shows Lyle Stuart reporting that Hubbard stated repeatedly that to make money, "you start a religion."

According to The Visual Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, ed. Brian Ash, Harmony Books, 1977:

- " . . . began making statements to the effect that any writer who really wished to make money should stop writing and develop religion, or devise a new psychiatric method. Harlan Ellison's version (Time Out, UK, No 332) is that Hubbard is reputed to have told Campbell, "I'm going to invent a religion that's going to make me a fortune. I'm tired of writing for a penny a word." Sam Moskowitz, a chronicler of science fiction, has reported that he himself heard Hubbard make a similar statement, but there is no first-hand evidence."

The following letter, written by L. Ron Hubbard, was discovered by the FBI during its raid on Scientology headquarters. The letter shows Hubbard turned Scientology into a "religion" for financial reasons:

(1953)

DEAR HELEN

10 APRIL

RE CLINIC, HAS The arrangements that have been made seem a good temporary measure. On a longer look, however, something more equitable will have to be organized. I am not quite sure what we would call the place - probably not a clinic - but I am sure that it ought to be a company, independent of the HAS [the Hubbard Association of Scientologists] but fed by the HAS. We don't want a clinic. We want one in operation but not in name. Perhaps we could call it a Spiritual Guidance Center. Think up its name, will you. And we could put in nice desks and our boys in neat blue with diplomas on the walls and 1. knock psychotherapy into history and 2. make enough money to shine up my operating scope and 3. keep the HAS solvent. It is a problem of practical business. I await your reaction on the religion angle. In my opinion, we couldn't get worse public opinion than we have had or have less customers with what we've got to sell. A religious charter would be necessary in Pennsylvania or NJ to make it stick. But I sure could make it stick. We're treating the present time beingness, psychotherapy treats the past and the brain. And brother, that's religion, not mental science.

Best Regards,

Ron

An article of Prof. Benjamin Beith-Hallahmi documents the secular aspects of Scientology from Scientology's own writings.

Free Zone

Main article: Free Zone (Scientology)The Church has taken steps to suppress the Free Zone and shut down dissenters when possible. The CoS has used copyright and trademark laws to attack various Free Zone groups.. Accordingly, the Free Zone avoids the use of officially trademarked Scientology words, including 'Scientology' itself. In 2000, the Religious Technology Center unsuccessfully attempted to gain the Web domain www.scientologie.org from the World Intellectual Property Organization, in a legal action against the Free Zone. Skeptic Magazine described the Free Zone as: "..a group founded by ex-Scientologists to promote L. Ron Hubbard's ideas independent of the COS ." A Miami Herald article wrote that ex-Scientologists joined the Free Zone because they felt that Church of Scientology leadership had: "..strayed from Hubbard's original teachings." One Free Zone Scientologist identified as "Safe", was quoted in Salon as saying: "The Church of Scientology does not want its control over its members to be found out by the public and it doesn't want its members to know that they can get scientology outside of the Church of Scientology".

Litigation as Harassment of Critics

| This section needs expansion. You can help by making an edit requestadding to it . (January 2008) |

In the past many critics of Scientology have claimed that they were harassed by frivolous lawsuits.

Paulette Cooper was falsely accused of felony charges as she had been framed by the Church of Scientology's Guardian's Office. Furthermore, her personal life had been intruded upon by cult members who had attempted to kill her and/or draw her to suicide in a covert plan known as Operation Freakout that was brought to light after FBI investigations into other matters (See Operation Snow White).

A prominent example of litigation of its critics is the Church of Scientology's $416 million dollar libel lawsuit against Time Warner as a result of their publication of a highly critical magazine article "The Thriving Cult of Greed and Power" by Richard Behar. A public campaign by the Church of Scientology accordingly ensued in an attempt to defame this Time Magazine publication. (See Church of Scientology's response)

Gareth Alan Cales is being harassed by the Church of Scientology, including false charges against him and his friends.

The purpose of the suit is to harass and discourage rather than to win. The law can be used very easily to harass, and enough harassment on somebody who is simply on the thin edge anyway, well knowing that he is not authorized, will generally be sufficient to cause his professional decease. If possible, of course, ruin him utterly.

— L. Ron Hubbard, A Manual on the Dissemination of Material, 1955

Similarly, the Church of Scientology's legal battle with Gerry Armstrong in Church of Scientology v. Gerald Armstrong spanned two decades and involved a $10 million claim against Armstrong.

Personality tests

Main article: Oxford Capacity AnalysisIn 2008 the 20 year old daughter of Ole Gunnar Ballo, a Norwegian member of parliament, had taken a personality test organized by Scientologists in Nice, and received very negative feedback from it. A few hours later she committed suicide. French police started an investigation of the Scientology church. In the wake of the Ballo suicide linked to the personality test, the spokesman for the church in Norway called the link at accusation deeply unfair, and pointing out that the daughter had previously suffered eating disorders and psychiatric troubles.

The personality test has been condemned by the psychologist Rudy Myrvang. He called the test a recruitment tool, aimed at breaking down a person so that the Scientologists can build the test-taker back up.

The Church of Scientology's replies to its critics

Scientology's response to accusations of criminal behavior has been twofold; the church is under attack by an organized conspiracy, and each of the church's critics is hiding a private criminal past. In the first instance, the Church of Scientology has repeatedly stated that it is engaged in an ongoing battle against a massive, worldwide conspiracy whose sole purpose is to "destroy the Scientology religion." Thus claiming that aggressive measures and legal actions are the only way the church has been able to survive in a hostile environment, they sometimes liken themselves to the early Mormons who took up arms and organized militia to defend themselves from persecution.

The church asserts that the core of the organized anti-Scientology movement is the psychiatric profession, in league with deprogrammers and certain government bodies (including elements within the FBI and the government of Germany.) These conspirators have allegedly attacked Scientology since the earliest days of the church, with the shared goal of creating a docile, mind controlled population. As an official Scientology website explains:

- To understand the forces ranged against L. Ron Hubbard, in this war he never started, it is necessary to gain a cursory glimpse of the old and venerable science of psychiatry-which was actually none of the aforementioned. As an institution, it dates back to shortly before the turn of the century; it is certainly not worthy of respect by reason of age or dignity; and it does not meet any known definition of a science, what with its hodgepodge of unproven theories that have never produced any result-except an ability to make the unmanageable and mutinous more docile and quiet, and turn the troubled into apathetic souls beyond the point of caring. That it promotes itself as a healing profession is a misrepresentation, to say the least. Its mission is to control.

On the other hand, L. Ron Hubbard proclaimed that the only reason anyone would attack Scientology is because that person or entity is a "criminal." Hubbard wrote on numerous occasions that all of Scientology's opponents are seeking to hide their own criminal histories, and the proper course of action to stop these attacks is to "expose" the hidden crimes of the attackers. The Church of Scientology does not deny that it vigorously seeks to "expose" its critics and enemies; it maintains that all of its critics have criminal histories, and they encourage hatred and "bigotry" against Scientology. Hubbard's belief that all critics of Scientology are criminals was summarized in a policy letter written in 1967:

- Now get this as a technical fact, not a hopeful idea. Every time we have investigated the background of a critic of Scientology we have found crimes for which that person or group could be imprisoned under existing law. We do not find critics of Scientology who do not have criminal pasts. Over and over we prove this. -- Critics of Scientology, "Hubbard Communications Office Policy Letter," 5 November 1967.

Scientology claims that it continues to expand and prosper despite all efforts to prevent it from growing; critics claim that the Church's own statistics contradict its story of continuing growth .

The Church of Scientology has published a number of responses to criticism, including Those Who Oppose Scientology, available online.

Analyses of Scientology's counter-accusations and actions against its critics are available on a number of websites, including the critical archive Operation Clambake.

See also

- Trapped in the Closet (South Park)

- Chilling Effects (group)

- Fight Against Coercive Tactics Network

- Believe What You Like

- Inside Scientology

- Bare-faced Messiah (book)

- Brain-Washing (book)

- Scientology and Me

- E-meter

- Galactic Confederacy

- Church of Scientology v. Gerald Armstrong

- R2-45

- Project Chanology

- Scientology beliefs and practices

- Scientology and the legal system

- Scientology and psychiatry

- Scientologie, Wissenschaft von der Beschaffenheit und der Tauglichkeit des Wissens

References

- Apology to Bonnie Woods from the Church of Scientology and other defendants, 8 June, 1999.

- Behar, Richard (1991-05-06). "The Scientologists and Me". Time.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Strupp, Joe (2005-06-30). "The press vs. Scientology". Salon. Retrieved 2007-09-19.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - http://www.xs4all.nl/~johanw/CoS/attacks-on-scn.txt

- Sweeney, John (14 May 2007). "Row over Scientology video". BBC News. Retrieved 2008-11-03.

- Adams, Stephen (15 May 2007). "BBC reporter blows his top at Scientologist". Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 2008-11-03.

- Sweney, Mark (14 May 2007). "Panorama backs Sweeney episode". The Guardian. Retrieved 2008-11-03.

- HCO Policy Letter Subject Index, page 215, issued 1976

- Enquiry into the Practice and Effects of Scientology: Report by Sir John Foster, K.B.E., Q.C., M.P. - Published by Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London, December 1971, Chapter 7 (also referred to as the Foster Report)

- L. Ron Hubbard. Organization Executive Course -- An Encyclopedia of Scientology Policy, vol. 1, p. 429, as cited in Atack, Jon (1990). A Piece of Blue Sky. New York, NY: Carol Publishing Group. ISBN 0-8184-0499-X.

- Ortega, Tony (1999-12-23). "Double Crossed". Phoenix New Times. New Times Media. Retrieved 2006-06-05.

- Garrison, Omar PLAYING DIRTY The Secret War Against Beliefs Ralton-Pilot, Los Angeles, 1980 pg 172-173 ISBN 0-931116-04-X

- The Commission of Inquiry Into the Hubbard Scientology Organisation in New Zealand; Chairman: Sir Guy Richardson Powles, K.B.E., C.M.G.; Member: E. V. Dumbleton, Esquire, June 1969, page 26

- The HCO Policy Letter Subject Index (1976) lists on page 211 the entry HCO PL 7 March 1969 Organization, although no copy is found in the HCO PL compilation volumes from that time

- http://www.lermanet2.com/reference/wollersheim.htm (courtesy link) Wollersheim v. Church of Scientology of California, Court of Appeal of the State of California, civ.no.B023193, 18 July 1989

- http://www.xs4all.nl/~johanw/CoS/hostile-contacts.txt

- Operation Clambake presents: ARS Acronym/Terminology FAQ

- DeSio, John (2007-05), "The rundown on Scientology's Purification Rundown", New York Press

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - http://www.religiousfreedomwatch.com/extremists/index.html

- Church of Scientology apology to Bonnie Woods from the Church of Scientology and other defendants, 8 June, 1999.

- Stars' cult pays out £155,000 over hate campaign, Richard Palmer, The Express, 8 June, 1999.

- Scientologists pay for libel, Clare Dyer, The Guardian, 9 June, 1999.

- "Libellous Flier Distributed by Scientology". Kristi Wachter. Retrieved 2006-07-13.

- ^ Operation Snow White - Part Two

- The E-Meter Papers - How Does Scientology Auditing Work? The Hidden Influence... Legal Case, July 30, 1971

- "What is the E-Meter and how does it work?". Church of Scientology International. Retrieved 2006-06-27.

- Morgan, Lucy (1999-03-29). "Abroad: Critics public and private keep pressure on Scientology". St. Petersburg Times. Retrieved 2007-11-04.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Catholic Sentinel, March 17, 1978

- Charles L. Stafford (1980-01-09). "Scientology: An in-depth profile of a new force in Clearwater" (PDF, 905K). St. Petersburg Times.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) Original (18M) - Koff, Stephen (1988-12-22). "Scientology church faces new claims of harassment". St. Petersburg Times. Retrieved 2008-04-19.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - CanLII - 1996 CanLII 1650 (ON C.A.)

- Henley, Jon (2001-06-01). "France arms itself with legal weapon to fight sects". The Guardian. Retrieved 2007-10-30.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - "France recommends dissolving Scientologists". BBC News. 2000-02-08. Retrieved 2007-11-04.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Scientology press release issued upon winning the CAN court battle and another view from the American Lawyer. June 1997

- "Nog dit jaar Belgisch proces tegen Scientology" ( – ). De Morgen. 2006. Retrieved 2006-07-23.

{{cite journal}}: External link in|format= - Belgium charges Scientologists with extortion. Sydney Morning Herald. Accessed 05 September 2007.

- Martin, Susan Taylor (2007-11-04). "Belgium builds case against Scientology". St. Petersburg Times. Retrieved 2007-11-04.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Police Received Gifts From Church Of Scientology (from Croydon Guardian)

- The Anderson Report - Contents

- ^ "21. The conclusion to which we have ultimately come is that Scientology is, for relevant purposes, a religion."

- Scientology beliefs 'stopped accused killer getting treatment' | The Australian

- Scientology associated deaths

- Tobin, Thomas C. (2000-03-09). "Scientologists decry toll of criminal case". St. Petersburg Times. Retrieved 2007-09-17.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Farley, Robert (2004-05-29). "Scientologists settle death suit". St. Petersburg Times. Retrieved 2007-09-17.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Scientology: The Thriving Cult of Greed and Power, Time, May 6, 1991, see article: The Thriving Cult of Greed and Power

- ^ Church of Scientology v. Time and Richard Behar, 92 Civ. 3024 (PKL), Opinion and Order, Court TV library Web site., retrieved 1/10/06.

- ^ "Judge Dismisses Church of Scientology's $416 Million Lawsuit Against Time Magazine", Business Wire, July 16, 1996.

- October 1991, Readers Digest, "A Dangerous Cult Goes Mainstream".

- Survey Reveals Physicians' Experience with Cults, Dr. Edward Lottick, Cult Observer, Volume 10, Number 3, 1993.

- ^ Morgan, Lucy (1998-02-08). "Scientology got blame for French suicide". St. Petersburg Times. Retrieved 2007-10-30.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Understanding Scientology / Chapter 14: Brainwashing and Thought Control in Scientology - The Road to Rondroid

- http://www.cesnur.org/2002/scient_rpf_01.htm The Church of Scientology's Rehabilitation Project Force]

- Family Torn Apart by Scientology

- ^ Robert Farley (2006-06-24). "The unperson". St. Petersburg Times. pp. 1A, 14A. Retrieved 2006-06-25.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Operation Clambake and ronthenut.org present: Andre Tabayoyon Affidavit

- Affidavit of Andre Tabayoyon, 5 March 1994, in Church of Scientology International vs. Steven Fish and Uwe Geertz.

- Hoffman, Claire (2005-12-18). "Tom Cruise and Scientology". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2006-11-14.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)< - Verfassungsschutz Bayern (Constitution Protection Bavaria: Publications (German)

- Church of Scientology: The Bonafides of the Scientology Religion

- http://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-news/ir-97-50.txt

- Church of the New Faith v. Commissioner Of Pay-roll Tax (Vict.) 1983, 154 CLR 120

- "Spanish court rules Scientology can be listed as a religion". November 1, 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|pub=ignored (|publisher=suggested) (help) - 2007 U.S. Department of State – 2007 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices: Portugal

- Italian Supreme Court decision, The Court of Appeals of Milan Decision

- "Scientology church in Sweden granted religious status". Associated Press. 2000-03-15. Retrieved 2008-05-19.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help), "Decision of March 13, 2000 registering Scientology as a "religious community" in Sweden". CESNUR. 2000-03-13. Retrieved 2007-07-21.{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) -

Davis, Derek H. (2004). "The Church of Scientology: In Pursuit of Legal Recognition" (PDF). Zeitdiagnosen: Religion and Conformity. Münster, Germany: Lit Verlag. Retrieved 2008-05-10.

{{cite conference}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help) - "Scientology gets tax-exempt status". New Zealand Herald. 2002-12-27. Retrieved 2007-08-01.

the IRD said the church was a charitable organisation dedicated to the advancement of religion

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Miller, Russell (1987). Bare-faced Messiah, The True Story of L. Ron Hubbard (First American Edition ed.). New York: Henry Holt & Co. pp. p.133. ISBN 0-8050-0654-0.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help);|pages=has extra text (help) - Sam Moskowitz affidavit, 14 April 1993

- "Inside Scientology". A&E Network. 1998-12-14. Retrieved 2007-01-27.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Marburg Journal of Religion - Scientology: Religion or Racket?

- Playing Dirty:The Secret War Against Beliefs, Omar V. Garrison, 1980

- Meyer-Hauser, Bernard F. (June 23, 2000). "Religious Technology Center v. Freie Zone E. V". Case No. D2000-0410.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Lippard, J. (1995). "Scientology v. the Internet. Free Speech & Copyright Infringement on the Information Super-Highway". Skeptic Magazine. pp. Vol. 3, No. 3., Pg. 35-41.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Staff (2005-07-02). "SCIENTOLOGY: What's Behind the Hollywood Hype?". Miami Herald.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Brown, Janelle (1999-07-22). "Copyright -- or wrong? : The Church of Scientology takes up a new weapon -- the Digital Millennium Copyright Act -- in its ongoing battle with critics". Salon.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Xenu.net

- LAist: Church of Scientology Strikes Back - Anonymous Responds

- WikiSource - Church of Scientology v. ArmstrongWikiSource - Church of Scientology v. Superior Court

- ^ Police probe suicide linked to Scientologists Aftenposten, April 16, 2008

- What was Behind Attacks on Scientology in Spain, France, Germany and Italy?

- The Real Issues - Those Who Oppose Scientology

- Narconon Exposed: Narconon And Its Critics

Notes

- Brinkema, Leonie M. Civil Action No. 95-1107-A: Memorandum Opinion, (Alexandria:US District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia—Alexandria Division, November 28, 1995)

- Hubbard, L. Ron. Attacks on Scientology, "Hubbard Communications Office Policy Letter," February 25, 1966

- All England Law Reports (London: Butterworths,1979), vol. 3 p. 97

- Transcript of judgement in B & G (Minors) (Custody) Delivered in the High Court(Family Division), London, 23 July 1984.

- EFF "Legal Cases - Church of Scientology" Archive

- Owen Chris. 'The strange links between the CoS-IRS agreement and the Snow White Program', Scientology vs the IRS, (16 January 1998)

- Washington Post, January 8, 1983

- Catholic Sentinel, March 17, 1978

- United States District District Court, District of Columbia (333 F. Supp. 357)

- Arizona Republic, September 22, 1988

- a Scientology Press Release, July 2, 1997

External links

- Church of Scientology views

- "Those Who Oppose Scientology". Main site: http://opposing.scientology.org.

{{cite web}}: External link in|work= - Misconceptions about Scientology ScientologyToday.org

- "Religious Freedom Watch: Defending religious rights". Web site campaigning against critics of Scientology.

{{cite web}}: Text "Owned and operated by the "Church" of Scientology - This according to the shield coverage and inclusion of I.P. 72.52.9.76" ignored (help) - "Response to Critics". Links of the Church of Scientology’s response to critics. Open Directory Project.

- Opposing views

- "Operation Clambake" (a comprehensive archive of critical material on Scientology )

- scientologists freezone" (A comparative study on the Church's and the Freezone's activity)

- The Fishman Affidavit: The case file for Church of Scientology International v. Fishman and Geertz

- Scientology-Lies.com What's Wrong with Scientology

- Scientology associated deaths A site focusing on those who died in circumstances allegedly linked to Scientology

- Dianetics Skeptic's Dictionary entry on dianetics

- Scientology Victims Testimonies Video testimonies of people who were victimized by Scientology organization