This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Fowler&fowler (talk | contribs) at 21:58, 7 January 2009. The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 21:58, 7 January 2009 by Fowler&fowler (talk | contribs)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)

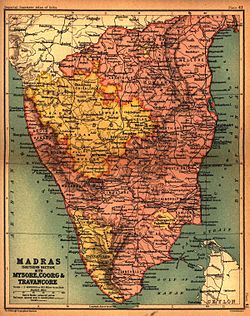

The history of Mysore and Coorg, 1565–1760 is the history of two contiguous regions that were later referred to as Mysore state and Coorg province respectively and that lie in peninsular India between approximately 11° 30′ and 15° N. latitude and 74° 40′ and 78° 40′ E. longitude (please see accompanying map); this history covers the period from the fall of the Vijayanagara Empire in southern India in 1565 to just before the usurpation of power in the region by Sultan Haidar Ali in 1761. From 1799 to 1947 Mysore was a princely state in the British Indian Empire, whereas Coorg was a minor province in British India; however, since their histories are intertwined, especially during the time period of interest here, they are being considered together.

During the period of greatest extent of the Vijayanagara empire (1350–1565) the region was ruled by various chieftains, called Nayakas, each with dominion over a small area and each required to pay an annual tribute to the emperor as well as to supply soldiers for the empire's needs. After the fall of the empire in 1565 and the subsequent eastwards move of the diminished ruling family, the region saw changing rule by different claimants. Many former Nayakas tried to assert their independence and simultaneously expand their dominions; in addition, various powers from the north: the sultanate of Bijapur, the Marathas and the Moghuls invaded the region and attempted to stake claims over different subregions. By the turn of the eighteenth century the situation had stabilized somewhat: the northwestern subregion was ruled by the Nayakas of Ikkeri, the southern by the Wodeyars of Mysore, and the eastern and northeastern by the Nawabs of Arcot and the Sira, respectively. However, some of the expansions undertaken in the southern region by the Wodeyars of Mysore, were based on unstable alliances; when the alliances began to unravel, as they did during the first half of the eighteenth century, the rule of the Wodeyars suffered a decline. In particular, the Nawab of Arcot, who considered Mysore to be a tributary of the Mughals and himself a representative of the latter, raided the Wodeyar capital to collect tribute; the Raja of Coorg was involved in a war of attrition over some western territory; and the Marathas again invaded the region and could be turned back only with the surrender of territory. The last decade of this period saw the rise of Haidar Ali in the southern principality ruled by the Wodeyars. Under him Mysore was to expand and become both a large independent kingdom covering most of southern India and a serious threat—the last indigenous one—to the burgeoning power of the English East India Company; however, that would happen after the period covered in this article.

Poligars of Vijayanagara

The last Hindu empire in South India, the Vijayanagara Empire was defeated on January 23, 1565 in the Battle of Talikota by the combined forces of the Muslim states of Bijapur, Golconda, and Ahmadnagar to its north. The battle was fought in Talikota on the doab (or "tongue" of land) between the Kistna river and its major left bank tributary, the Bhima, some 100 miles north of the imperial capital of Vijayanagara (please see map). The invaders later destroyed the capital, and the ruler's family escaped to Penukonda, 125 miles southeast, where they established their new capital. Although before long they would move their capital another 175 miles east-southeast to Chandragiri and would survive there until 1635, their dwindling empire would now concentrate its resources on its eastern Tamil and Telugu speaking realms. According to Subhrahmanyam 2001b harvnb error: no target: CITEREFSubhrahmanyam2001b (help),

"... in the ten years following 1565, the imperial centre of Vijayanagara effectively ceased to be a power as far as the western reaches of the peninsula were concerned, leaving a vacuum that was eventually filled by Ikkeri and Mysore."

Earlier, in the heyday of their rule, the kings of Vijayanagara had granted tracts of lands throughout their realm to various vassal chiefs, on the stipulation of "paying tribute and rendering military service." The chiefs in the northern regions were supervised directly from the capital; however, the Vijayanagara emperors could collect only part of the revenue from their empire's richer but more distant southern provinces. Consequently, the chiefs in the south were overseen by a viceroy, with title Sri Ranga Raya, based in Seringapatam (now Srirangapatna), an island town on the river Cauvery (now Kaveri), some 200 miles south of the capital. The chiefs bore various formal titles. These included the title Nayaka, assumed by the Nayakas of Kelladi, (and later of Ikkeri and Bednur, see accompanying map) in the northwestern wooded hills, by the Nayakas of Basavapatna, and Nayakas of Chitaldroog (now Chitradurga) in the north, the Nayakas of Belur in the west, and the Nayakas of Hegalvadi in the centre; the title Gowda, assumed by the Gowdas of Ballapur and of Yelahanka in the center, and the Gowdas of Sugatur in the east; and Wodeyar, assumed by the Wodeyars of Mysore, of Kalale and of Ummatur in the south. (Please see accompanying map.)

The greater distances of these chiefdoms from the Vijayanagara capital was not the only reason for the somewhat tenuous hold the Vijayanagara center had on its southern periphery. The centralization imposed by the empire was also resisted by these chiefs (also called rajas, or "little kings," if their realms were more substantial) for moral and political reasons; according to Stein 1985b harvnb error: no target: CITEREFStein1985b (help):

"'Little kings', or rajas, never attained the legal independence of an aristocracy from both monarchs and the local people whom they ruled. The sovereign claims of would-be centralizing, South Indian rulers and the resources demanded in the name of that sovereignty diminished the resources which local chieftains used as a kind of royal largesse; thus centralizing demands were opposed on moral as well as on political grounds by even quite modest chiefs."

Somewhat incorrectly, these chiefs came to called poligars, a British corruption of "Palaiyakkarar" (literally holder of "palaiya"or "baronial estate").

Declining imperial presence

Meanwhile, almost a decade after their victories at Raichur, the Deccan sultanates of Bijapur and Ahmadnagar agreed in 1573 to not interfere in each others future conquests by reserving regions to the south for Bijapur. In 1577, Bijapur forces attacked again and overwhelmed all opposition along the western coast. They also took Adoni, a former Vijayanagara stronghold, and attempted next to take Penukonda, the new Vijayanagara capital. (Please see accompanying map.) There, however, they were repulsed by an army led by the Vijayanagra ruler's father-in-law, Jagadeva Raya, who had traveled north for the engagement from his base in Baramahal. For his services, Jagadeva Raya's territories within the crumbling empire were vastly expanded, extending west now up to the Western Ghats and with a new capital in Channapatna

The territories controlled by the other poligars were also changing fast. Some, such as Tamme Gowda of Sigatur, expanded their's by performing services for the Vijayanagara monarch and receiving territorial rewards, which in his case consisted of a tract of land which, from Sigatur, extended west to Hoskote and east to Punganur; others, such as the Wodeyars of Ummattur and of Mysore, achieved the same end by ignoring the monarch altogether, and annexing small states in their vicinity. Through much of the 16th century, the chiefs of Ummattur in particular had carried on "unceasing aggression" against their neighbors, even in the face of punitive raids by the Vijayanagara armies themselves. In the end, as a compromise, the son of a defeated Ummatur chief was appointed the governor or viceroy at Seringapatam. However, the Wodeyars of Mysore too were eying surrounding land; by 1610, Raja Wodeyar of Mysore had ousted the "effete" Vijayanagara viceroy at Seringapatam, and soon, expanding southwards, captured Ummatur in 1613. (Please see accompanying map.) During his rule, according to (Stein 1987) harv error: no target: CITEREFStein1987 (help), his "chiefdom expanded into a major principality." In 1630, the Wodeyars of Mysore added Channapatna, Jagadeva Raya's capital, to their dominions; by 1644, when the Wodeyars unseated the powerful Changalvas of Piriyapatna, not only had they become the dominant presence in the southern regions of what later became Mysore state, but the Vijayanagara empire was also on its last legs, having only a year's life left.

In the northwest and farther south, other chiefs were asserting their independence as well. By the turn of the seventeenth century, according to (Subrahmanyam 2001b) harv error: no target: CITEREFSubrahmanyam2001b (help):

"there had emerged several principalities, all of which were notionally subordinate to Vijayanagara, and some of which paid what would in northern India be termed an annual peshkash, a sum that was frequently quite large. In most other senses, and certainly where fiscal and general administration within their territories was concerned, these Nayaka rulers—under which head one can include not only Madurai and Tanjavur, but Ikkeri and Udaiyar Mysore—were operatively independent."

Shadow of the Mughals

The Sultans of Bijapur, for their part—some sixty years after their defeat at Penukonda—regrouped and struck again in 1636. They did so now with the blessing to the Mughal empire of Northern India, whose tributaries they had recently become. They also had the help of an Maratha chieftain of western India, Shahaji Bhonsle, who was on the lookout for rewards of jagir land in the conquered territories, and whose son, Shivaji Bhonsle would found the Maratha Empire some 30 years later. In the western-central poligar regions, the Bijapur forces at best achieved mixed results. The Nayakas of Kelladi, now installed in nearby Bednur, were decisively defeated; however, they were soon able to buy back their realms from their invaders. The attack on Seringapatam was repulsed by Kanthirava, the reigning Wodeyar of Mysore, with great losses to the enemy.

In the east, the Bijapur-Shahji forces were more successful: in 1639, they took possession of Bangalore, founded earlier by Kempe Gowda, and the Kolar district. Next, moving down the Eastern Ghats they captured Vellore and Gingee. On their return journey, through the maidan plains, they gained possession of Ballapur, Sira, and Chitaldroog. The new possessions that were situated above (or westwards of) the Eastern Ghats, such as Kolar, Hoskote, Bangalore, and Sira, were incorporated into a new province named Caranatic-Bijapur-Balaghat, which was now granted to Shahji as a jagir. (Please see accompanying map.) The new possessions below the Ghats, such as Gingee and Vellore became part of another province, named Carnatic-Bijapur-Payanghat, with Shahji named the first governor. When Shahji died in 1664, his son, Venkoji (also Ekoji I), from his second wife, who meanwhile had become the Nayaka of Tanjore farther south, inherited these territories. However, this did not sit well with Shivaji—Shahji's oldest son, from his first wife—who now led an expedition southwards to claim his fair share. Shivaji's quick victories resulted in a partition, whereby both the Carnatic-Bijapur provinces became his dominions, and whereas the Nayakaship of Tanjore was retained by Venkoji.

The successes of Bijapur and Shivaji, however, were being watched warily by the major imperial presence in the subcontinent, the Mughal Empire in North India. Aurengzeb, who had become the Mughal emperor in 1659, decided the destroy the Sultanates of Bijapur and Golconda as well as the burgeoning Maratha power of Shivaji. In 1686, the Mughals took Bijapur and, the following year, Golconda. Soon, fast moving Mughal armies were bearing down on the former Vijayanagara dominions. In 1687, a new Mughal province (or suba) was created with capital in Sira. The province consisted of seven parganas (districts): Basavapatna, Budihal, Sira, Penukonda, Dod-Ballapur, Hoskote, and Kolar; in addition, it had Harpanahalli, Kondarpi, Anegundi, Bednur, Chitaldroog, and Mysore as tributary states. Bangalore, quickly taken by the Mughals from the Marathas, was sold to the Raja of Mysore for 3 lakh rupees. Qasim Khan was appointed the first Mughal governor of the Province of Sira, with title Faujdar Diwan (literally, "military governor")

Seventeenth century Mysore

Although their own histories date the origins of the Wodeyars of Mysore (also "Odeyar," "Wodiyar," or "Wadiar," literally "chief") to 1399, records of them go back no earlier than the early sixteenth century, and according to (Subrahmanyam 2001) harv error: no target: CITEREFSubrahmanyam2001 (help) even the late sixteenth or early seventeenth centuries. These poligar chieftains are first mentioned in a Kannada literary work in the early 16th century. A petty chieftain, Chamaraja (now Chamaraja III), who ruled from 1513 to 1553, and who had dominion over a few villages not far from the river Kaveri, is said to have constructed a small fort and named it, Mahisura-nagara, (literally, "buffalo town") from which Mysore gets its name. This wodeyar clan issued its first inscription during the chieftaincy of Timmaraja (now Timmaraja II) who ruled from 1553 to 1572. Towards the end of his rule, he is recorded to have owned 33 villages and fielded an army of 300 men. During this time, as already mentioned above, these Wodeyars, like other Nayaks in the region, were poligars of the Vijayanagara Empire.

By the time of the short-lived incumbency of Timmaraja II's son, Chama Raja IV, who, already well into his 60s, ruled from 1572 to 1576, the Vijayanagara Empire had been dealt its death blow in the Battle of Talikota mentioned above. Before long, Chama Raja IV withheld payment of the annual tribute to the now weakened empire's viceroy at Seringapatam. This led to the the viceroy attempting, without success, to arrest the Wodeyar. In 1578, however, Chama Raja IV's eldest son, Raja I, became the Wodeyar of Mysore, and with his rule the family's power became more firmly established. For, it was Raja I, who, in 1610, captured Seringapatm from the aging Vijayanagara viceroy, Tirumala Raji, and, in a matter of days, on 8 February 1610, moved his capital there. Raja I, who would rule until 1617, went on to annex Ummattur, as already mentioned above.

Raja I, his only son having predeceased him, was succeeded upon his death in 1617, by his grandson, the 14-year-old Bettada Chamaraja V. Chamaraja V, who reigned under the Regency of Delavoi (Prime Minister), Bettada Urs, until he 1622, would go on to continue the policies of his grandfather, which included undermining or subduing other Wodeyars and simultaneously placating the cultivators in the ryots. In 1630, he captured Jagadeva Raya's capital of Channapattana and with that a large tract of land fell into the Mysore Wodeyar hands. Chamaraja V, who married five times, died soon after his 34th birithday; at his funeral, all his surviving wives committed sati.

Chamaraja V was succeeded by his uncle, who in turn was quickly poisoned on the orders of the Delavoi Vikramaraya within a year of becoming the wodeyar. The 23-year-old Kanthirava Narasaraja I, who had earlier been adopted by the widow of Raja I, became, in 1638, the new Wodeyar of Mysore. Soon after his accession, he was called on to defend Seringapatam against the Bijapur invasions, defense, which as already noted, he mounted with great loss for enemy. In the fashion of the two wodeyars before him, he continued to expand the Mysore dominions. This included taking Satyamangalam from the Nayaks of Madurai in the south, unseating the Chingalvas from their base in Piriyapatna in the west, gaining possession of Hosur (near Salem) to the north and and delivering a major blow at Yelahanka to the rule of Kempe Gowda of Magadi, from whom a large tribute was exacted. Kanthirava Narasaraja I was also the first wodeyar of Mysore to create the symbols associated with royalty, such as establishing a mint and issuing coins named Kanthiraya (corrupted to "Canteroy") after him. These were to remain a part of Mysore's "current national money" for well over a century. Kanthirava Narasaraja I, who married ten times, died on 31st July 1659, at the age of 44. At his funeral, all his surviving wives committed sati.

The deceased wodeyar was succeeded by his cousin, Dodda Kempadevaraja (also Doddadevaiya Urs), who ruled until 1672. During his rule, the last of the Vijayanagara rulers sought refuge in Bednur. Soon afterwards, Sivappa Naik, the Nayaka of Kelladi attacked Seringapatam with a large force and with the ostensible intention of restoring Vijayanagara rule at Seringapatam. However, the Mysore forces, led by Doda Kempadevaraja, repulsed the attack and thereafter pursued the attackers into the malnad region to the west, where they captured more territory. Dodda Kempadevaraja also abrogated his nominal allegiance to Vijayanagar and declared his kingdom to be independent. Soon the Naiks of Madura invaded Mysore as well; they too were repulsed and chased back into their own dominions, where Erode and Dharapuram were annexed to Mysore and Trichonopoly was forced to pay tribute to Mysore. When the king died in Chiknayakanhalli, the northernmost outpost of his territories, in 1672, his dominions had considerably expanded. They extended now to Dharapuram in Coimbatore in the south, Sakkarepatna (now Chikmagalur) to the west, and Salem to the east.

Chikka Devaraja

The deceased ruler's 27-year-old nephew, Chikka Devaraja, succeeded him in 1672 as the new wodeyar. Chikka Devaraja continued his predecessor's expansion by conquering Maddagiri, and thereby making Mysore contiguous to the Carnatic-Bijapur-Balaghat province administered by Venkoji, the Raja of Tanjore, and Shivaji's half-brother. During his rule centralized military power increased to an unprecedented degree for the region; In the first decade of his rule, Chikka Devaraja introduced various petty taxes that were mandatory for the peasants, but that his soldiers' were exempted from. The unusually high taxes and the intrusive nature of his regime, created wide protests in the ryots which had the support of the Jangama priests in the Virasaiva monasteries. According to (Nagaraj 2003) harv error: no target: CITEREFNagaraj2003 (help), a slogan of the protests was:

"Basavanna the Bull tills the forest land; Devendra gives the rains;

Why should we, the ones who grow crops through hard labor, pay taxes to the king?"

The king, resolving upon a "treacherous massacre," used the stratagem of inviting over 400 hundred priests to a grand feast at the famous Shaivite center of Nanjanagudu, and upon its conclusion having them first receive gifts and then exit one at a time through a narrow lane, whereupon his royal wrestlers strangled each exiting priest. This "sanguinary measure" had the effect of stopping all protests to the new taxes. Around this time, 1687, Chikka Devaraja also made an agreement with Venkoji to purchase Bangalore (what later became Bangalore district) for Rs. 3 lakhs.

However, soon thereafter, the Mughals under Aurangzeb invaded the region and, having conquered the Maratha-Bijapur province of Carnatic-Bijapur-Balaghat (of which Bangalore was a part), made it a part of the Mughal province of Sira. The payment for Bangalore was consequently made to Qasim Khan, the Mughal Faujdar Diwan of Sira (alluded to above) and through him Chikka Devaraja "assiduously cultivated an alliance" with Aurangzeb. He also soon turned his attention to the regions to his south which were less the objects of Moghul interest. The regions around Baramahal and Salem below the Eastern Ghats were now annexed to Mysore, and in 1694 were extended by the addition of regions to the west up to the Baba Budan mountains. Two years later Chikka Devaraja attacked the lands of the Naik of Madura and laid a siege of Trichinopoly. Soon, however, Qasim Khan, his Mughal liaison, died. With the intention of either renewing his Mughal connections or seeking Mughal recognition of his southern conquests, Chikka Devaraja sent an embassy to Aurangzeb at Ahmadnagar. In response, in 1700, the Mughal emperor sent the Mysore Raja a signet ring "bearing the title Jug Deo Raj and permission to sit on an ivory throne." Chikka Devaraja at this time also reorganized his administration into eighteen departments, in "imitation of what the envoys had seen at the Mughal court." When the Raja died on 16 November 1704, his dominions extended from Midagesi in the north to Palni and Anaimalai in the south, and from Coorg and Balam in the west to Baramahals in the east.

According to Subrahmanyam 1989 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFSubrahmanyam1989 (help), the state that Chikka Devaraja left for his son was "at one and the same time a strong and a weak state." Although it had uniformly expanded in size from the mid-seventeenth century to the early eighteenth, it had done so a result of alliances that tended to hinder the very stability of the expansions. Some of the southeastern conquests described above (such as of Salem), although involving regions that were not of direct interest to the Mughals, were nonetheless the result of alliances with Mughal Faujdar Diwan of Sira and with Venkoji, the Maratha ruler of Tanjore. For example, the siege of Trichnopoly had to be abandoned because the alliance had begun to rupture. Similarly, in addition to receiving a signet ring described above, a consequence of the embassy sent to Aurangzeb in the Deccan in 1700 was formal subordination to Mughal authority and a requirement to pay annual tribute. There is evidence too that the administrative reforms mentioned above might have been a direct result of Mughal influence.

Ikkeri and the Kanara trade

In the northern regions, according to (Stein 1987) harv error: no target: CITEREFStein1987 (help),

"an even more impressive chiefly house that arose in Vijayanagara times and came to enjoy an extensive sovereignty. These were the Keladi chiefs who later founded the Nayaka kingdom of Ikkeri. At its greatest, the Ikkeri rajas controlled a territory nearly as large as the Vijayanagara heartland, some 20,000 square miles, extending about 180 miles south from Goa along the trade-rich Kanara coast."

When Vasco da Gama landed in Calicut in 1498, the Vijayanagara empire was about to reach the apex of its power. During the Vijayanagara rule in the sixteenth century the chieftaincies, or Nayakas principalities, of Keladi (and later of Ikkeri and Bednur) were established in the western part of what later became Shimoga district. The first of the Kaladi chiefs, was Sadasiva Raya Naik, and to him was granted the administering of some towns on the Kanara coast. In the decade after the fall of the Vijayanagara empire, the Portuguese decided, as a commercial strategy, to hedge their bets in the pepper trade and commenced purchasing some of their pepper from the Kanara region, instead of relying, as they had in the past, entirely on the Malabar coast farther south. During 1568–1569, they took possession of the coastal towns of Onor (now Honavar), Barcelor (now Basrur), and Mangalore and constructed fortresses and factories at each location. (Please see accompanying map.)

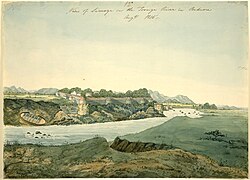

Onor was located on the banks of the Sharavathi River, two miles upstream from the mouth, where the river widened into a lake. The Portuguese fort was built strategically on a cliff overlooking the river and contained homes for thirty casados (married settlers); furthermore, a natural sandbank kept out the large ocean-going ships, and left the harbour accessible only to small craft. Approximately, 35 miles farther upstream, the Portuguese maintained a weighing station at Gersoppa, where they purchased the pepper. During the latter part of the sixteenth century and the first half of the seventeenth, Onor was to become not only the principal port for the export of Kanara pepper, but also the most important Portuguese supply point for pepper in all of Asia.

Located some 50 miles south of Onor, and a few miles up the Coondapoor estuary (now Varahi) was the town of Barcelore (now Basrur). The Portuguese built their fortress downstream of the pre-existing Hindu town in order to control any approaches from the sea. The fortress had accommodation for some 30 casados; another 35 casados and their families lived in a walled area a stone's throw. Barcelore became a busy trading centre which exported rice, local textiles, saltpeter, and iron from the interior regions and imported corals, exotic yard goods and horses.

Fifty miles south of Barcelore, and the last of the Portuguese strongholds in Kanara, was Mangalore, situated on the mouth of the Netravati River. There too the Portuguese built a fortress and alongside it a walled town with accommodation for 35 casados families. Both Barcelore and Mangalore became principal ports for the export of rice and during the first half of the seventeenth century would supply the many strategic fortalezas that were of significance to the Estado da India, the Portuguese Asian empire. These included, Goa, Malacca, Muscat, Mozambique and Mombasa.

With the fall of the Vijayanagara empire, Venkatappa Naik, whom the Portuguese referred to as Venkapor, king of Kanara, and before whose time the capital had already been moved to Ikkeri, now "assumed independence." Soon with the Bijapur raids threatening the region, his successor moved the capital once again to Bednur (later Nagar which was deemed safer. Sivappa Naik, who commenced ruling in 1645, rapidly took possession of a region that extended east to Shimoga, south to Manjarabad, and west through most of the Kanara coast. When, soon afterwards, the last king of Vijayanagara sought refuge in his realms, Sivappa Naik set him up at Belur and Sakkarepatna, and later mounted an unsuccessful siege of Seringapatam on the latter's behalf, which has already been briefly alluded to earlier. After his death in 1660, his successors managed to control the region until 1763, at which time, Haidar Ali took possession of it and declared the intention of making a new capital now referred to as Nagar.

Eighteenth century Mysore

The early eighteenth century saw the rule of Kanthirava Narasaraja II, who, being both deaf and mute, ruled under the Regency of a series of Delavoys from the Kalale family. Upon the ruler's death in 1714 at the age of 41, his son, Dodda Krishnaraja I, still two weeks shy of his 12th birthday, succeeded him.

Under Dodda Krishnaraja I, the political role of the Mysore Rajas gradually began to be eclipsed and would remain so until the end of the nineteenth century. For the remaining first half of the nineteenth century, this power would be exercised by three Delavoys, Nanjaraj, his cousin Devaraj, and latter's younger brother (also named) Nanjaraj. During this time various armies belonging to the Nawab of Sira, his rival the Nawab of Arcot, or the Mughal subedar of the Deccan, trooped through Mysore for the purpose of exacting tributes they claimed were owed them. In 1757, when the Peshwas under Balaji Rao, turned up, "so impoverished had the State become that several taluks were pledged to them" as a price of withdrawal.

Eighteenth century Coorg

According to a "royal" genealogy produced in 1808, the princely line was established by a member of the Keladi Nayak family, who having settled in Haleri, north of Mercara, in the disguise of a Jangama or Lingayat priest, soon took possession of the entire country. One of his successors, Muddu Raja, shifted his capital to Madikeri or Mercara and constructed both a fortress and a palace there. Upon his death, his oldest son Dodda Virappa, succeeded him at Mercera, whereas his other two sons, Appaji Raja and Nanda Raja, took control of Haleri and Horamale respectively. In 1690, when Chikka Devaraja invaded the Belur region, which included Manjarabad, Dodda Virappa annexed the Yelusavira region to Coorg; however, he was forced to pay a yearly half-tax to the wodeyars of Mysore as the price of possession. Soon, upon assisting the ruler Chirakkal Raja against Somasekhara Naik of Bednur, Virappa gained the northwestern Amara Sulya district for this kingdom. The Coorg region would remain in the control of the family until it was annexed to British India in 1834.

Sources and historiography

There is very little contemporaneous documentation of the pre-1760 period of Mysore's history, especially the last century of that period. According to (Subrahmanyam 1989, p. 206) harv error: no target: CITEREFSubrahmanyam1989 (help), the 18th-century Wodeyar rulers of Mysore—in contrast to their contemporaries in Rajputana, Central India, Maratha Deccan, and Tanjavur—left little or no record of their administrations.

A Wodeyar dynasty genealogy, the Maisüru Maharäjara Vamśävali or the Chikkadevaräya Vamśävali of Tirumalarya, was composed in Kannada during the period 1710–1715, and was claimed to be based on all the then-extant inscriptions in the region. Another genealogy, Kalale Doregala Vamśävali, of the Delvoys, the near-hereditary chief ministers of Mysore, was composed around the turn of the 19th century. However, neither manuscript provides information about administration, economy or military capability. The ruling dynasty's origins, especially as expounded in later palace genealogies, are also of doubtful accuracy; this is, in part, because the Wodeyars, who were reinstated by the British on the Mysore gaddi in 1799, to preside over a fragile sovereignty, "obsessively" attempted to demonstrate their "unbroken" royal lineage, to bolster their then uncertain status.

The earliest manuscript offering clues to governance and military conflict in the pre-1760 Mysore, seems to be (Dias 1725), an annual letter written in Portuguese by a Mysore-based Jesuit missionary, Joachim Dias, and addressed to his Provincial superior. After East India Company's final 1799 victory over Tipu, official Company records began to be published as well; these include (East India Company 1800), a collection of Anglo-Mysore Wars-related correspondence between the Company's officials in India and Court of Directors in London, and (Wilks 1805), the first report on the new Princely State of Mysore by its first British resident, Mark Wilks. Around this time, French accounts of the Anglo-Mysore wars appeared as well, and included (Michaud 1809), a history of the wars by Joseph-François Michaud, another Jesuit priest. The first attempt at including a comprehensive history of Mysore in an English language work is (Buchanan 1807) harv error: no target: CITEREFBuchanan1807 (help), an account of a survey of South India conducted at Lord Richard Wellesley's request, by Francis Buchanan, a Scottish physician and geographer.

The first explicit History of Mysore in English is (Wilks 1811), written by Mark Wilks, the British resident mentioned above. Wilks claimed to have based his history on various Kannada documents, not only the ones mentioned above, but also many that have not survived. According to (Subrahmanyam 1989, p. 206) harv error: no target: CITEREFSubrahmanyam1989 (help), all subsequent classic histories of Mysore have borrowed heavily from Wilks's book for their pre-1760 content. These include, (Rice 1897) harv error: no target: CITEREFRice1897 (help), Lewis Rice's well-known Gazetteer and (Rao 1948), C. Hayavadana Rao's major revision of the Gazetteer half a century later, and many spin-offs of these two works. By the end of the period of British Commissionership of Mysore (1831–1881), many English language works had begun to appear on a variety of Mysore-related subjects. These included (Rice 1879), a book of English translations of Kannada language inscriptions, and (Digby 1878), William Digby's two volume critique of British famine policy during the Great Famine of 1876–78, which devastated Mysore for years to come; the latter work, even referred to Mysore as a "province."

See also

Notes

- ^ Imperial Gazetteer of India: Provincial Series 1908, p. 16 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFImperial_Gazetteer_of_India:_Provincial_Series1908 (help)

- Imperial Gazetteer of India: Provincial Series 1908, p. 17 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFImperial_Gazetteer_of_India:_Provincial_Series1908 (help), Subrahmanyam 2001b, p. 133 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFSubrahmanyam2001b (help)

- Subrahmanyam 2001b, p. 133 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFSubrahmanyam2001b (help)

- Sen 2007, p. 356 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFSen2007 (help)

- ^ Imperial Gazetteer of India: Provincial Series 1908, p. 17 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFImperial_Gazetteer_of_India:_Provincial_Series1908 (help)

- Imperial Gazetteer of India: Provincial Series 1908, p. 17 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFImperial_Gazetteer_of_India:_Provincial_Series1908 (help), Stein 1987, pp. 49–50 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFStein1987 (help)

- ^ Michell 1995, p. 18 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFMichell1995 (help)

- Stein 1985b, p. 392 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFStein1985b (help)

- ^ Imperial Gazetteer of India: Provincial Series 1908, pp. 17–18 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFImperial_Gazetteer_of_India:_Provincial_Series1908 (help)

- Imperial Gazetteer of India: Provincial Series 1908, pp. 17–18 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFImperial_Gazetteer_of_India:_Provincial_Series1908 (help), Stein 1987, p. 83 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFStein1987 (help)

- ^ Stein 1987, p. 83 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFStein1987 (help)

- Stein 1987, p. 82 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFStein1987 (help)

- ^ Imperial Gazetteer of India: Provincial Series 1908, p. 18 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFImperial_Gazetteer_of_India:_Provincial_Series1908 (help)

- ^ Imperial Gazetteer of India: Provincial Series 1908, p. 19 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFImperial_Gazetteer_of_India:_Provincial_Series1908 (help)

- Ramusack 2004, p. 28 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFRamusack2004 (help).

- ^ Stein 1987, p. 82 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFStein1987 (help)

- Subrahmanyam 2001, p. 68 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFSubrahmanyam2001 (help)

- Stein 1987, p. 82 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFStein1987 (help), Manor 1975, p. 33 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFManor1975 (help)

- Ramusack 2004, p. 28 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFRamusack2004 (help)

- Manor 1975, p. 33 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFManor1975 (help)

- ^ Imperial Gazetteer of India: Provincial Series 1908, pp. 19–20 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFImperial_Gazetteer_of_India:_Provincial_Series1908 (help)

- ^ Imperial Gazetteer of India: Provincial Series 1908, p. 20 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFImperial_Gazetteer_of_India:_Provincial_Series1908 (help)

- Bandyopadhyay 2004, p. 33 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFBandyopadhyay2004 (help), Stein 1985b, pp. 400–401 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFStein1985b (help)

- Stein 1985b, pp. 400–401 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFStein1985b (help)

- Stein 1985b, pp. 400–401 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFStein1985b (help), Imperial Gazetteer of India: Provincial Series 1908, pp. 20–21 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFImperial_Gazetteer_of_India:_Provincial_Series1908 (help)

- ^ Nagaraj 2003, pp. 378–379 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFNagaraj2003 (help)

- ^ Imperial Gazetteer of India: Provincial Series 1908, pp. 20–21 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFImperial_Gazetteer_of_India:_Provincial_Series1908 (help)

- Subrahmanyam 1989, p. 212 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFSubrahmanyam1989 (help)

- ^ Subrahmanyam 1989, p. 213 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFSubrahmanyam1989 (help)

- Stein 1987, pp. 83–84 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFStein1987 (help)

- Disney 1978, p. 2 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFDisney1978 (help)

- ^ Imperial Gazetteer of India: Provincial Series 1908, p. 239 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFImperial_Gazetteer_of_India:_Provincial_Series1908 (help)

- ^ Disney 1978, p. 4 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFDisney1978 (help)

- ^ Disney 1978, p. 5 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFDisney1978 (help)

- Ames 2000, p. 11 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFAmes2000 (help), Disney 1978, p. 5 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFDisney1978 (help)

- ^ (Subrahmanyam 1989, p. 206) harv error: no target: CITEREFSubrahmanyam1989 (help)

- Ikegame 2007, p. 17 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFIkegame2007 (help)

- Nair 2006, pp. 139–140 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFNair2006 (help)

- Bhagavan 2008, pp. 887 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFBhagavan2008 (help)

- Subrahmanyam 1989, pp. 215–216 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFSubrahmanyam1989 (help)

References

Contemporary sources

|

|