This is an old revision of this page, as edited by 82.4.220.242 (talk) at 15:21, 10 April 2009. The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 15:21, 10 April 2009 by 82.4.220.242 (talk)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Presidential election results map. Red denotes states won by Harding/Coolidge, Blue denotes those won by Cox/Roosevelt. Numbers indicate the number of electoral votes allotted to each state. Presidential election results map. Red denotes states won by Harding/Coolidge, Blue denotes those won by Cox/Roosevelt. Numbers indicate the number of electoral votes allotted to each state. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The United States presidential election of 1920 was dominated by the aftermath of World War I and the hostile reaction to Woodrow Wilson, the Democratic president. The wartime boom had collapsed. Politicians were arguing over peace treaties and the question of America's entry into the League of Nations. Overseas there were wars and revolutions; at home, 1919 was marked by major strikes in meatpacking and steel, and large race riots in Chicago and other cities. Terrorist attacks on Wall Street produced fears of radicals and terrorists.

Outgoing President Wilson had become increasingly unpopular, and following his severe stroke in 1919 could no longer speak on his own behalf. The economy was in a recession, the public was weary of war and reform, the Irish Catholic and German communities were outraged at his policies, and his sponsorship of the League of Nations produced an isolationist reaction.

Former President Theodore Roosevelt had been the frontrunner for the Republican nomination, but his health had collapsed in 1918 and he died in January 1919, leaving no obvious heir to his Progressive legacy. Both major parties turned to dark horse candidates from the electoral vote-rich state of Ohio. The Democrats nominated newspaper publisher and Governor James M. Cox; in turn the Republicans chose Senator Warren G. Harding, another Ohio newspaper publisher. Cox launched an energetic campaign against Senator Harding,and did all he could to defeat him. To help his camapign, he chose Franklin D. Roosevelt as his running mate. Harding virtually ignored Cox and essentially campaigned against Wilson,calling for a return to "normalcy"; and, with an almost 4-to-1 spending advantage, won a landslide victory. Harding's victory remains the largest popular-vote percentage margin (60.3% to 34.1%) in Presidential elections after the so-called "Era of Good Feelings" ended with the victory of James Monroe in the election of 1820.

Nominations

Republican Party nomination

Republican candidates

-

Senator Warren G. Harding of Ohio

Senator Warren G. Harding of Ohio

-

Major General Leonard Wood of New Hampshire

Major General Leonard Wood of New Hampshire

-

Governor Frank Orren Lowden of Illinois

Governor Frank Orren Lowden of Illinois

-

Senator Hiram Johnson of California

Senator Hiram Johnson of California

-

Governor William Cameron Sproul of Pennsylvania

Governor William Cameron Sproul of Pennsylvania

- Columbia University President and 1912 V.P. nominee Nicholas Murray Butler of New York Columbia University President and 1912 V.P. nominee Nicholas Murray Butler of New York

-

Governor Calvin Coolidge of Massachusetts

Governor Calvin Coolidge of Massachusetts

-

Senator Robert M. La Follette, Sr. of Wisconsin

Senator Robert M. La Follette, Sr. of Wisconsin

On June 8, the Republican National Convention met in Chicago. The race was wide open, and soon the convention deadlocked between General Leonard Wood and Governor Frank O. Lowden of Illinois.

Others placed in nomination included Senators Warren G. Harding of Ohio, Hiram Johnson of California, and Miles Poindexter of Washington, Governor Calvin Coolidge of Massachusetts, Herbert Hoover, and Columbia University President Nicholas Murray Butler. Senator Robert M. La Follette, Sr. of Wisconsin was not formally placed in nomination but received the votes of his state delegation, nonetheless. Harding was nominated for President on the tenth ballot, after shifts. The ten ballots went like this:

| Presidential Balloting, RNC 1920 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ballot | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 Before shifts | 10 After shifts |

| Warren G. Harding | 65.5 | 59 | 58.5 | 61.5 | 78 | 89 | 105 | 133 | 374.5 | 644.7 | 692.2 |

| Leonard Wood | 287.5 | 289.5 | 303 | 314.5 | 299 | 311.5 | 312 | 299 | 249 | 181.5 | 156 |

| Frank Lowden | 211.5 | 259.5 | 282.5 | 289 | 303 | 311.5 | 311.5 | 307 | 121.5 | 28 | 11 |

| Hiram Johnson | 133.5 | 146 | 148 | 140.5 | 133.5 | 110 | 99.5 | 87 | 82 | 80.8 | 80.8 |

| William C. Sproul | 84 | 78.5 | 79.5 | 79.5 | 82.5 | 77 | 76 | 76 | 78 | 0 | 0 |

| Nicholas Murray Butler | 69.5 | 41 | 25 | 20 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Calvin Coolidge | 34 | 32 | 27 | 25 | 29 | 28 | 28 | 30 | 28 | 5 | 5 |

| Robert M. La Follette | 24 | 24 | 24 | 22 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 |

| Jeter C. Pritchard | 21 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Miles Poindexter | 20 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 14 | 2 | 0 |

| Howard Sutherland | 17 | 15 | 9 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Herbert C. Hoover | 5.5 | 5.5 | 5.5 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 10.5 | 9.5 |

| Scattering | 11 | 9 | 7 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 5.5 | 3.5 |

Harding's nomination, said to have been secured in negotiations among party bosses in a "smoke-filled room," was engineered by Harry M. Daugherty, Harding's political manager who after Harding's election became United States Attorney General. Prior to the convention, Daugherty was quoted as saying, "I don't expect Senator Harding to be nominated on the first, second, or third ballots, but I think we can afford to take chances that about 11 minutes after two, Friday morning of the convention, when 15 or 12 weary men are sitting around a table, someone will say: 'Who will we nominate?' At that decisive time, the friends of Harding will suggest him and we can well afford to abide by the result." Daugherty's prediction described essentially what occurred, but historians Richard C. Bain and Judith H. Parris argue that Daugherty's prediction has been given too much weight in narratives of the convention.

Once the presidential nomination was finally settled, the party bosses and Sen. Harding recommended Wisconsin Sen. Irvine Lenroot to the delegates for the second spot, but the delegates revolted and nominated Coolidge, who was very popular over his handling of the Boston Police Strike of the year before. The Tally:

| Vice Presidential Balloting, RNC 1920 | |

|---|---|

| Calvin Coolidge | 674.5 |

| Irvine L. Lenroot | 146.5 |

| Henry J. Allen | 68.5 |

| Henry Anderson | 28 |

| Asle J. Gronna | 24 |

| Hiram Johnson | 22.5 |

| Jeter C. Pritchard | 11 |

| Abstaining | 9 |

Source for convention coverage: Richard C. Bain and Judith H. Parris, Convention Decisions and Voting Records (Washington DC: Brookings Institution, 1973), pp. 200-208.

Democratic Party nomination

Democratic Candidates:

-

Former Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan of Nebraska

-

Governor James M. Cox of Ohio

Governor James M. Cox of Ohio

-

DNC Chairman Homer Stille Cummings of Connecticut

DNC Chairman Homer Stille Cummings of Connecticut

-

Former Solicitor General and Ambassador to the United Kingdom John W. Davis of West Virginia

Former Solicitor General and Ambassador to the United Kingdom John W. Davis of West Virginia

-

Governor Edward I. Edwards of New Jersey

Governor Edward I. Edwards of New Jersey

-

Former Ambassador to Germany James W. Gerard of New York

Former Ambassador to Germany James W. Gerard of New York

-

Secretary of Treasury Carter Glass of Virginia

Secretary of Treasury Carter Glass of Virginia

-

Governor of the Philippine Islands Francis B. Harrison of New York

Governor of the Philippine Islands Francis B. Harrison of New York

-

Former Secretary of Treasury William G. McAdoo of California

Former Secretary of Treasury William G. McAdoo of California

-

Senator Robert L. Owen of Oklahoma

Senator Robert L. Owen of Oklahoma

-

Attorney General Alexander Mitchell Palmer of Pennsylvania

Attorney General Alexander Mitchell Palmer of Pennsylvania

-

Senator Furnifold McLendel Simmons of North Carolina

Senator Furnifold McLendel Simmons of North Carolina

-

Governor Al Smith of New York

Governor Al Smith of New York

-

President Woodrow Wilson of New Jersey

President Woodrow Wilson of New Jersey

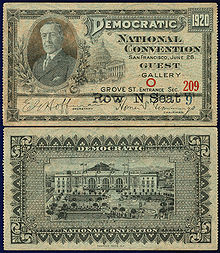

Although William Gibbs McAdoo (Wilson's son-in-law and former Treasury Secretary) was the strongest candidate, Wilson blocked his nomination in hopes a deadlocked convention would demand Wilson run for a third term. (Wilson at the time was physically immobile and in seclusion.) The Democrats, meeting in San Francisco, nominated another newspaper editor from Ohio, Governor James M. Cox, as their presidential candidate, and 38 year-old Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt, a fifth cousin of the late president Teddy Roosevelt, for vice president.

Early favorites for the nomination had included McAdoo and Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer. Others placed in nomination included New York Governor Al Smith, New Jersey Governor Edward I. Edwards, and former Solicitor General John W. Davis.

General election

Return to normalcy

See also: NormalcyWarren Harding's main campaign slogan was a "return to normalcy", playing upon the weariness of the American public after the social upheaval of the Progressive Era. Additionally, World War I and the Treaty of Versailles proved deeply unpopular, causing a reaction against Wilson who had pushed especially hard for the latter.

Ethnic issues

Irish Americans were powerful in the Democratic party and opposed going to war alongside their enemy Britain, especially after the violent suppression of the Easter Rebellion of 1916. Wilson won them over in 1917 by promising to ask Britain to give Ireland its independence. At Versailles, however, he reneged and the Irish American community vehemently denounced him. Wilson in turn blamed the Irish Americans and German Americans for the lack of popular support for the League of Nations, saying, "There is an organized propaganda against the League of Nations and against the treaty proceeding from exactly the same sources that the organized propaganda proceeded from which threatened this country here and there with disloyalty, and I want to say -- I cannot say too often -- any man who carries a hyphen about with him carries a dagger that he is ready to plunge into the vitals of this Republic whenever he gets ready."

In response, the Irish American city machines sat on their hands during the election, allowing the Republicans to roll up unprecedented landslides in every major city. Many German American Democrats voted Republican or stayed home, giving the GOP landslides in the rural Midwest.

Campaign

Wilson had hoped for a “solemn referendum” on the League of Nations, but did not get one. Harding waffled on the League, thereby keeping the “irreconcilables” like Senator William Borah in line. Cox also hedged. He went to the White House for Wilson's blessing and apparently endorsed the League, but—discovering its unpopularity among Democrats—he said that he wanted the League only with reservations, particularly on Article Ten, which would require the United States to participate in any war declared by the League. (That is, he took the same position as Republican Senate leader Henry Cabot Lodge.) As reporter Brand Whitlock observed, the League was an issue important in government circles, but was unimportant to the electorate. He also noted that the campaign was not being waged on issues: “The people, indeed, do not know what ideas Harding or Cox represents; neither do Harding or Cox. Great is democracy.” False rumors circulated that Harding had "Negro blood," but this did not greatly hurt Harding's election campaign.

Cox made a whirlwind campaign that took him to rallies, train station speeches, and formal addresses, reaching audiences totaling perhaps 2 million. Harding relied upon a “Front Porch Campaign” similar to that of William McKinley in 1896. It brought thousands of voters to Marion, Ohio where Harding spoke from his home. GOP campaign manager Will Hays spent about $8,100,000, nearly four times the money Cox spent. Hays used national advertising in a major way (with advice from adman Albert Lasker). The theme was Harding's own slogan “America First”. Thus the Republican advertisement in Collier's Magazine for October 30, 1920 demanded, “Let's be done with wiggle and wobble.” The image presented in the ads was nationalistic, using catch phrases like “absolute control of the United States by the United States,” “Independence means independence, now as in 1776,” “This country will remain American. Its next President will remain in our own country,” and “We decided long ago that we objected to foreign government of our people.”

On election night, November 2, 1920, commercial radio broadcast coverage of election returns for the first time. Announcers at KDKA-AM in Pittsburgh read telegraph ticker results over the air as they came in. This single station could be heard over most of the Eastern United States by the small percentage of the population that had radio receivers.

Harding's landslide came from all directions except the deep South. Irish American and German American voters who had backed Wilson and peace in 1916 now voted against Wilson and Versailles. “A vote for Harding,” said the German-language press, “is a vote against the persecutions suffered by German-Americans during the war.” Not one major German-language newspaper supported Cox. The Irish Americans, bitterly angry at Wilson's refusal to help Ireland at Versailles, sat out the election. Since they controlled the Democratic party in most large cities, this allowed the Republicans to mobilize the ethnic vote, and Harding swept the big cities.

This was the first election in which women from every state were allowed to vote, following the passage of the 19th Amendment to the Constitution in August 1920 (only in time for the general election, however).

Tennessee's vote for Warren G. Harding marked the first time since the end of Reconstruction that one of the 11 states of the Confederacy had voted for a Republican.

Despite the fact that Cox was defeated badly, his running-mate, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, became a well-known political figure because of his active and energetic campaign. In 1928 he was elected Governor of New York, and in 1932 he was elected President and remained in power until his death in 1945, as the longest-serving President ever.

Other candidates

Socialist Party candidate Eugene V. Debs received 913,664 popular votes (3.4%), despite the fact that he was in prison at the time for advocating non-compliance with the draft in the war. This was the largest amount of popular votes ever received by a Socialist Party candidate in the United States, though not the largest percentage of the popular vote. (The 19th Amendment had dramatically increased the number of people eligible to vote.) Debs received double this percentage in the election. The 1920 election was his fifth and last attempt to become president.

Parley P. Christensen of the Farmer-Labor Party took 265,411 votes (1.0%), while Prohibition Party candidate Aaron S. Watkins came in fifth with 189,339 votes (0.7%), the poorest showing for the Prohibition party since 1884; as the Eighteenth Amendment starting Prohibition had passed the previous year, this single-issue party seemed less relevant.

Results

| Presidential candidate | Party | Home state | Popular vote | Electoral vote |

Running mate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | Percentage | Vice-presidential candidate | Home state | Electoral vote | ||||

| Warren Gamaliel Harding | Republican | Ohio | 16,144,093 | 60.3% | 404 | Calvin Coolidge | Massachusetts | 404 |

| James Middleton Cox | Democratic | Ohio | 9,139,661 | 34.1% | 127 | Franklin Delano Roosevelt | New York | 127 |

| Eugene Victor Debs | Socialist | Indiana | 913,693 | 3.4% | 0 | Seymour Stedman | Illinois | 0 |

| Parley Parker Christensen | Farmer-Labor | Illinois | 265,411 | 1.0% | 0 | Maximillian Sebastian Hayes | Ohio | 0 |

| Aaron Sherman Watkins | Prohibition | Indiana | 188,787 | 0.7% | 0 | David Leigh Colvin | New York | 0 |

| James Edward Ferguson | American | Texas | 47,968 | 0.2% | 0 | William Jervis Hough | New York | 0 |

| William Wesley Cox | Socialist Labor | Missouri | 31,716 | 0.1% | 0 | August Gilhaus | New York | 0 |

| Robert Colvin Macauley | Single Tax | Pennsylvania | 5,750 | 0.0% | 0 | Richard C. Barnum | 0 | |

| Other | 27,746 | 0.1% | — | Other | — | |||

| Total | 26,765,180 | 100% | 531 | 531 | ||||

| Needed to win | 266 | 266 | ||||||

Source (Popular Vote): Leip, David. "1920 Presidential Election Results". Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections. Retrieved July 28, 2005.Source (Electoral Vote): "Electoral College Box Scores 1789–1996". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved July 31, 2005.

See also

- History of the United States (1918–1945)

- History of the United States Democratic Party

- History of the United States Republican Party

- United States Senate election, 1920

Notes

- American Rhetoric, "Final Address in Support of the League of Nations", Woodrow Wilson, delivered September 25, 1919 in Pueblo, CO.

- Sinclair, p. 168

- Sinclair, p. 162

- Sinclair, p. 163

- http://www.presidentelect.org/e1912.html

References

- Bagby, Wesley M. (1968). The Road to Normalcy: The Presidential Campaign and Election of 1920.

- Boller, Paul F., Jr. (2004). Presidential Campaigns: From George Washington to George W. Bush. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 212–217. ISBN 0-19-516716-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- John Milton Cooper. Breaking the Heart of the World: Woodrow Wilson and the Fight for the League of Nations (2001)

- John B. Duff, "German-Americans and the Peace, 1918-1920" American Jewish Historical Quarterly 1970 59(4): 424-459.

- John B. Duff, "The Versailles Treaty and the Irish-Americans" Journal of American History 1968 55(3): 582-598. ISSN 0021-8723

- Donald R. McCoy, "The Election of 1920," in History of American Presidential Elections, ed Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. and Fred L. Israel, (1971),

- John A Morello. Selling the President, 1920: Albert D. Lasker, Advertising, and the Election of Warren G. Harding (2001)

- Sinclair, Andrew (1965). The Available Man: The Life behind the Masks of Warren Gamaliel Harding.

- Web sites

-

- "The Presidential Election of 1920". American Leaders Speak: Recordings from World War I and the 1920 Election. Library of Congress. Retrieved November 16 2002.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help)

- "The Presidential Election of 1920". American Leaders Speak: Recordings from World War I and the 1920 Election. Library of Congress. Retrieved November 16 2002.

External links

- 1920 popular vote by counties

- 1920 Election Links

- How close was the 1920 election? - Michael Sheppard, Michigan State University