This is an old revision of this page, as edited by 119.95.176.131 (talk) at 00:17, 19 May 2009. The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 00:17, 19 May 2009 by 119.95.176.131 (talk)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| Battle of Plataea | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Greco-Persian Wars | |||||||||

Engraving showing the view of Plataea from Mount Cithaeron | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Greek city-states | Achaemenid Empire | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Pausanias | Mardonius † | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

110,000 (Herodotus) 100,000 (Pompeius) about 40,000 (Modern consensus) |

300,000 (Herodotus) 120,000 (Ctesias) 70,000 - 120,000 (Modern consensus, including Greek allies) | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

10,000+ (Ephorus and Diodorus) 1,360 (Plutarch) 159 (Herodotus) |

257,000 (Herodotus) 10,000+ (Modern estimates) | ||||||||

| Greco-Persian Wars | |

|---|---|

The Battle of Plataea was the final land battle during the second Persian invasion of Greece. It took place in 479 BC near the city of Plataea in Boeotia, and was fought between an alliance of the Greek city-states, including Sparta, Athens, Corinth and Megara, and the Persian Empire of Xerxes I.

The previous year, the Persian invasion force, led by the Persian king in person, had scored victories at the Battles of Thermopylae and Artemisium, and conquered Thessaly, Boeotia and Attica. However, at the ensuing Battle of Salamis, the Allied Greek navy had won an unlikely victory, and therefore prevented the conquest of the Peloponnesus. Xerxes then retreated with much of his army, leaving his general Mardonius to finish off the Greeks the following year.

In the Summer of 479 BC, the Greeks assembled a huge army (by contemporary standards), and marched out of the Peloponnesus. The Persians retreated to Boeotia, and built a fortified camp near Plataea. The Greeks, however, refused to be drawn into the prime cavalry terrain around the Persian camp, resulting in a stalemate for 11 days. However, whilst attempting a retreat after their supply lines were disrupted, the Greek battle-line fragmented. Thinking the Greeks in full retreat, Mardonius ordered his forces to pursue them, but the Greeks (particularly the Spartans, Tegeans and Athenians) halted and gave battle, routing the lightly-armed Persian infantry and killing Mardonius.

A large portion of the Persian army was trapped in their camp, and slaughtered. The destruction of this army, and the remnants of the Persian navy, allegedly on the same day at the Battle of Mycale, decisively ended the invasion. After Plataea and Mycale, the Greek Allies would take the offensive against the Persians, marking a new phase of the Greco-Persian Wars. Although Plataea was in every sense a decisive victory, it does not seem to have been attributed the same significance (even at the time) as, for example the Athenian victory at the Battle of Marathon or even the Allied defeat at Thermopylae.

Background

Main articles: Greco-Persian Wars, First Persian invasion of Greece, and Second Persian invasion of GreeceThe Greek city-states of Athens and Eretria had supported the unsuccessful Ionian Revolt against the Persian Empire of Darius I in 499-494 BC. The Persian Empire was still relatively young, and prone to revolts amongst its subject peoples. Moreover, Darius was a usurper, and had spent considerable time extinguishing revolts against his rule. The Ionian revolt threatened the integrity of his empire, and Darius thus vowed to punish those involved (especially those not already part of the empire). Darius also saw the opportunity to expand his empire into the fractious world of Ancient Greece. A preliminary expedition under Mardonius, in 492 BC, to secure the land approaches to Greece ended with the re-conquest of Thrace and forced Macedon to become a client kingdom of Persia. An amphibious task force was then sent out under Datis and Artaphernes in 490 BC, successfully sacking Naxos and Eretria, before moving to attack Athens. However, at the ensuing Battle of Marathon, the Athenians won a remarkable victory, which resulted in the withdrawal of the Persian army to Asia.

Darius therefore began raising a huge new army with which he meant to completely subjugate Greece. However, he died before the invasion could begin. The throne of Persia passed to his son Xerxes I, who quickly re-started the preparations for the invasion of Greece, including building two pontoon bridges across the Hellespont. In 481 BC, Xerxes sent ambassadors around Greece asking for earth and water as a gesture of their submission, but making the very deliberate omission of Athens and Sparta (both of whom were at open war with Persia). Support thus began to coalesce around these two leading states. A congress of city states met at Corinth in late autumn of 481 BC, and a confederate alliance of Greek city-states was formed (hereafter referred to as 'the Allies'). This was remarkable for the disjointed Greek world, especially since many of the city-states in attendance were still technically at war with each other.

The Allies initially adopted a strategy of blocking the land and sea approaches to southern Greece. Thus, in August 480 BC, after hearing of Xerxes's approach, a small Allied army led by the Spartan king Leonidas I blocked the Pass of Thermopylae, whilst an Athenian-dominated navy sailed to the Straits of Artemisium. Famously, the massively outnumbered Greek army held Thermopylae against the Persians army for six days in total, before being outflanked by a mountain path. Although much of the Greek army retreated, the rearguard, formed of the Spartan and Thespian contingents, was surrounded and annihilated. The simultaneous Battle of Artemisium, consisting of a series of naval encounters, was up to that point a stalemate; however, when news of Thermopylae reached them, they also retreated, since holding the straits of Artemisium was now a moot point.

Following Thermopylae, the Persian army had proceeded to burn and sack the Boeotian cities which had not surrendered, Plataea and Thespiae; before taking possession of the now-evacuated city of Athens. The allied army, meanwhile, prepared to defend the Isthmus of Corinth. Xerxes wished for a final crushing defeat of the Allies to finish the conquest of Greece in that campaigning season; conversely the allies sought a decisive victory over the Persian navy that would guarantee the security of the Peloponnese. The ensuing naval Battle of Salamis ended in a decisive victory for the Allies, marking a turning point in the conflict.

Following the defeat of his navy at the Salamis, Xerxes retreated to Asia with the bulk of the army. According to Herodotus, this was because he feared the Greeks would sail to the Hellespont and destroy the pontoon bridges, thereby trapping his army in Europe. He thus left Mardonius, with handpicked troops, to complete the conquest of Greece the following year. Mardonius evacuated Attica, and wintered in Thessaly; the Athenians then reoccupied their destroyed city. Over the winter, there seems to have been some tension between the Allies. In particular, the Athenians, who were not protected by the Isthmus, but whose fleet were the key to the security of the Peloponnese, felt hard done by, and demanded an allied army march north the following year. When the Allies failed to commit to this, the Athenian fleet refused to join the Allied navy in spring. The navy, now under the command of the Spartan king Leotychides, thus skulked off Delos, whilst the remnants of the Persian fleet skulked off Samos, both sides unwilling to risk battle. Similarly, Mardonius remained in Thessaly, knowing an attack on the Isthmus was pointless, whilst the Allies refused to send an army outside the Peloponnese.

Mardonius moved to break the stalemate by trying to win over the Athenians and their fleet through the mediation of Alexander I of Macedon, offering peace, self-government and territorial expansion. The Athenians made sure that a Spartan delegation was also on hand to hear the offer, and rejected it:

The degree to which we are put in the shadow by the Medes' strength is hardly something you need to bring to our attention. We are already well aware of it. But even so, such is our love of liberty, that we will never surrender.

Upon this refusal, the Persians marched south again. Athens was again evacuated and left to the Persians. Mardonius now repeated his offer of peace to the Athenian refugees on Salamis. Athens, along with Megara and Plataea, sent emissaries to Sparta demanding assistance, and threatening to accept the Persian terms if not. According to Herodotus, the Spartans, who were at that time celebrating the festival of Hyacinthus, delayed making a decision until they were persuaded by a guest, Chileos of Tegea, who pointed out the danger to all of Greece if the Athenians surrendered. When the Athenian emissaries delivered an ultimatum to the Spartans the next day, they were amazed to hear that a task force was in fact already en route; the Spartan army was marching to meet the Persians.

Prelude

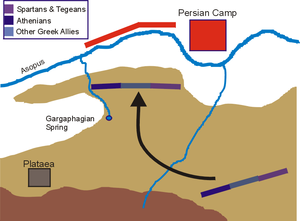

When Mardonius learned of the Spartan force, he completed the destruction of Athens, tearing down whatever was standing. He then retreated towards Thebes, hoping to lure the Greek army into territory which would be suitable for the Persian cavalry. Mardonius created a fortified encampment on the north bank of the Asopus river in Boeotia, and waited for the Greeks.

The Athenians sent 8,000 hoplites, led by Aristides, along with 600 Plataean exiles, to join the Allied army. The army then marched in Boeotia across the passes of Mount Cithaeron, arriving near Plataea, and above the Persian position on the Asopus. Under the guidance of the commanding general, Pausanias, the Greeks took up position opposite the Persian lines, but remained on high ground. Knowing that he had little hope of successfully attacking the Greek positions, Mardonius sought to either sow dissension amongst the Allies, or lure them down into the plain. Plutarch reports that a conspiracy was discovered amongst some prominent Athenians, who were planning to betray the Allied cause; although this account is not universally accepted, it may indicate Mardonius's attempts to intrigue with the Greeks.

Mardonius also sent hit-and-run cavalry attacks against the Greek lines, possibly trying to lure the Greeks down to the plain in pursuit. Although initially having some success, this strategy backfired when the cavalry commander Masistius was killed, whereupon the cavalry retreated.

Their morale boosted by this small victory, the Greeks moved forward, still remaining on higher ground, to a new position nearer Mardonius's camp.. The Spartans and Tegeans were on a ridge to the right of the line, the Athenians on a hillock on the left, and the other contingents on the slightly lower ground between. In response Mardonius brought his men up to the Asopus, and arrayed them for battle. However, both sides refused to attack; Herodotus claims this is because both sides received bad omens during sacrificial rituals. The armies thus stayed camped in their present locations for 8 days, and all the while new Greek troops arrived. Mardonius then sought to break the stalemate by sending his cavalry to attack the passes of Mount Cithaeron; this raid resulted in the capture of a convoy of provisions intended for the Greeks. Two further days passed, during which time the supply lines of the Greeks continued to be menaced. Mardonius then launched a further cavalry raid on the Greek lines, which succeeded in blocking the Gargaphian Spring, which had been the only source of water for the Greek army (they could not use the Asopus due to the threat posed by the Persian archers). Coupled with the lack of food, the restriction of the water supply made the Greek position untenable, so they decided to retreat to a position in front of Plataea, from where they could guard the passes and have access to fresh water. To prevent the Persian cavalry attacking the retreat, it was to be performed that night.

However, the retreat went badly awry. The Allied contingents in the centre missed their appointed position, and ended up scattered in front of Plataea itself. The Athenians, Tegeans and Spartans, who had been guarding the rear of the retreat, had not even begun to retreat by daybreak. A single Spartan division was thus left on the ridge to guard the rear, whilst the Spartans and Tegeans retreated uphill; Pausanias also instructed the Athenians to begin the retreat and if possible to join up with the Spartans.. However, the Athenians at first retreated directly towards Plataea, and thus the Allied battle line remained fragmented as the Persian camp began to stir.

The opposing forces

The Greeks

According to Herodotus, the Spartans sent 45,000 men; 5,000 Spartiates (full citizen soldiers), 5,000 other Lacedaemonian hoplites (perioeci) and 35,000 helots (seven per Spartiate). This was probably the largest Spartan force ever assembled. The Greek army had been reinforced by contingents of hoplites from the other Allied city-states, as shown in the table.

| City | Number of hoplites |

City | Number of hoplites |

City | Number of hoplites |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sparta | 10000 | Athens | 8000 | Corinth | 5000 |

| Megara | 3000 | Sicyon | 3000 | Tegea | 1500 |

| Phlius | 1000 | Troezen | 1000 | Anactorium & Leukas |

800 |

| Epidaurus | 800 | Orchomenian Arcadians |

600 | Eretria & Styra |

600 |

| Plataea | 600 | Aegina | 500 | Ambracia | 500 |

| Chalcidice | 400 | Mycenae & Tiryns |

400 | Hermione | 300 |

| Potidaea | 300 | Cephalonia | 200 | Lepreum | 200 |

| Total | 38,700 |

According to Herodotus, there were a total of 69,500 lightly armed troops; 35,000 helots, and 34,500 troops from the rest of Greece; roughly one per hoplite. The number of 34,500 has been suggested to represent 1 light troop supporting each non-Spartan hoplite (33,700), together with 800 Athenian archers, whose presence in the battle Herodotus later notes. Herodotus also tells us that there were also 1,800 Thespians (but not how they were equipped), giving a total strength of 110,000 men.

The number of hoplites is accepted as reasonable (and possible); the Athenians alone had fielded 10,000 hoplites at the Battle of Marathon. Some historians have accepted the number of light troops and used them as a population census of Greece at the time. Certainly these numbers are theoretically possible. Athens, for instance, allegedly fielded a fleet of 180 triremes at Salamis, manned by approximately 36,000 rowers. Thus 69,500 light troops could easily have been sent to Plataea. Nevertheless, the number of light troops is often rejected as exaggerated, especially in view of the ratio of 7 helots to 1 Spartiate. For instance, Lazenby accepts that hoplites from other Greek cities might have been accompanied by 1 lightly armoured retainer each, but rejects the number of 7 helots per Spartiate. He further speculates that each Spartiate was accompanied by 1 armed helot, and the remaining helots were employed in the logistical effort, transporting food for the army. Both Lazenby and Holland deem the lightly armed troops, whatever their number, as essentially irrelevant to the outcome of battle.

A further complication is that a certain proportion of Allied manpower was needed to man the fleet, which amounted to at least 110 triremes, and thus approximately 22,000 men. Since the Battle of Mycale was fought at least near-simultaneously with the Battle of Plataea, then this was a pool of manpower which could not have contributed to Plataea, and further reduces the likelihood that 110,000 Greeks assembled before Plataea.

The Greek forces were, as agreed by the Allied congress, under the overall command of Spartan Royalty in the person of Pausanias. Pausanias was the regent for Leonidas's young son, Pleistarchus, his cousin. Diodorus tells us that the Athenian contingent was under the command of Artistides; it is probable that the other contingents also had their leader. Herodotus tells us in several places that the Greeks held council during the prelude to the battle, implying that decisions were consensual, and that Pausanias did not have the authority to issue direct orders to the other contingents. This style of leadership contributed to the way events unfolded during the battle itself. For instance, in the period immediately before the battle, Pausanias was unable to order the Athenians to join up with his forces, and thus the Greeks fought the battle completely separated from each other.

The Persians

According to Herodotus, the Persians numbered 300,000 and were accompanied by troops from Greek city states which supported the Persian cause (including Thebes). Herodotus admits that no-one counted the latter, so he guesses that there were 50,000 of them.

Ctesias, who wrote a history of Persia based on Persian archives, claimed there were 120,000 Persian and 7,000 Greek soldiers, but his account is generally garbled (for instance, placing this battle before Salamis). Nevertheless, his figure is remarkably close to that generated by modern consensus.

The figure of 300,000 has been doubted, along with many of Herodotus's numbers, by many historians; modern consensus estimates the total number of troops for the Persian invasion at around 250,000. According to this consensus, Herodotus's 300,000 Persians at Plataea would self-evidently be impossible. One approach to estimating the size of the Persian army has been to estimate how many men might feasibly have been accommodated within the Persian camp; this approach gives figures of between 70,000 and 120,000 men. Lazenby, for instance, by comparison with later Roman military camps calculates a number of 70,000 troops, including 10,000 cavalry. Meanwhile, Connolly derives a number of 120,000 from the same sized camp. Indeed, most estimates for the total Persian force are generally in this range. For instance, Delbrück, based on the distance the Persians marched in a day when Athens was attacked, concluded that 75,000 was the upper limit for the size of the army.

Strategic and tactical considerations

In some ways, the run-up to Plataea resembled that at the Battle of Marathon; there was a prolonged stalemate in which neither side risked attacking the other. The reasons for this stalemate were primarily tactical, and similar to the situation at Marathon; the Greek hoplites did not want to risk being outflanked by the Persian cavalry, and the lightly armed Persian infantry could not hope to assault well defended positions.

According to Herodotus, both sides wished for a decisive battle which would tip the war in their favour. However, Lazenby believed that Mardonius's actions during the Plataea campaign were not consistent with an aggressive policy. He interprets the Persian operations during the prelude not as attempts to force the Allies into battle, but as attempts to force the Allies into retreat (which indeed became the case). Mardonius may have felt he had little to gain in battle, and that he could simply wait for the Greek alliance to fall apart (as it had nearly done over the winter). There can be little doubt from Herodotus's account that Mardonius was prepared to accept battle on his own terms however. Regardless of the exact motives, the initial strategic situation allowed both sides to procrastinate, since food supplies were in ample supply for both armies. Under these conditions, the tactical considerations outweighed the strategic need for action.

When Mardonius's raids disrupted the Allied supply chain, it forced a strategic rethink on the part of the Allies. Rather than now moving to attack, however, they instead looked to retreat and secure their lines of communication. Despite this defensive move from the Greeks, it was in fact the chaos resulting from this retreat which finally ended the stalemate. Mardonius perceived this as a full-on retreat, in effect thinking that the battle was already over, and sought to pursue the Greeks. Since he did not expect the Greeks to fight, the tactical problems were no longer an issue, and he tried to take advantage of the altered strategic situation he thought he had produced. Conversely, the Greeks had, inadvertently, lured Mardonius into attacking them on the higher ground and, despite being outnumbered, were thus at a tactical advantage.

The Battle

Once the Persians discovered that the Greeks had abandoned their positions, and appeared to be in retreat, Mardonius decided to set off in immediate pursuit with the elite Persian infantry. As he did so, the rest of the Persian army, unbidden, also began to move forward. The Spartans and Tegeans had by now reached the Temple of Demeter. The rearguard under Amompharetus began to withdraw from the ridge, under pressure from Persian cavalry, to join them. Pausanias sent a messenger to the Athenians, asking them to join up with the Spartans. However, the Athenians had been engaged by the Theban phalanx, and unable to assist Pausanias. The Spartans and Tegeans were first assaulted by the Persian cavalry, whilst the Persian infantry made their way forward. The Persian infantry then planted their shields and began firing arrows at the Greeks, whilst the cavalry withdrew.

According to Herodotus, Pausanias refused to advance, because good omens were not divined in the goat-sacrifices that were performed. At this point, as men began to fall under the barrage of arrows, the Tegeans started to run at the Persian lines. Offering one last sacrifice and a prayer to the heavens, Pausanias finally received favourable omens, and gave the command for the Spartans to advance, whereupon they too charged the Persian lines.

The numerically superior Persian infantry were of the heavy (by Persian standards) sparabara formation, but this was still much lighter than the Greek phalanx. The Persian defensive weapon was a large wicker shield, and they used short spears; by contrast the hoplites were armoured in bronze, with a bronze shield and a long spear. As at Marathon, it was a severe mismatch. The fight was fierce and long, but the Greeks continued to push into the Persian lines. The Persians tried to break the Greeks' spears by grabbing hold of them, but the Greeks were able to use their swords instead. Mardonius was present at the scene, riding a white horse, and surrounded by a bodyguard of 1,000 men, and whilst he remained, the Persians stood their ground. However, the Spartans closed in on Mardonius, and a stone thrown by the Spartan Aeimnestus hit him in the head, killing him. With Mardonius dead, the Persians began to flee, although his bodyguard remained and were annihilated. Quickly the rout became general, with many Persians fleeing in disorder to their camp. However, Artabazus (who had earlier commanded the Sieges of Olynthus and Potidea), had disagreed with Mardonius about attacking the Greeks, and he had not fully engaged the forces under his command. As the rout commenced, he led these men (40,000 according to Herodotus) away from the battle field, on the road to Thessaly, hoping to escape eventually to the Hellespont.

On the opposite side of the battle field, the Athenians had triumphed in a tough battle against the Thebans. The other Greeks fighting for the Persians had deliberately fought badly, according to Herodotus. The Thebans retreated from the battle, but in a different direction from the Persians, allowing them to escape without further losses. The Allied Greeks, reinforced by the contingents who had not taken part in the main battle, then stormed the Persian camp. Although the Persians initially defended the wall vigorously, it was eventually breached; and the Persians, packed tightly together in the camp, were slaughtered by the Greeks. Of the Persians who had retreated to the camp, scarcely 3,000 were left alive.

According to Herodotus, only 43,000 Persians survived the battle. The number who died of course depends on how many there were in the first place; there would be 257,000 dead by Herodotus's reckoning. Herodotus claims that the Greeks as a whole lost only 159 men. Furthermore, he claims that only Spartans, Tegeans and Athenians died, since they were the only ones who fought. Plutarch, who had access to other sources, gives 1,360 Greek casualties, while both Ephorus and Diodorus Siculus tally the Greek casualties to over 10,000.

Accounts of individuals

Herodotus recounts several anecdotes about the conduct of specific Spartans during the battle.

- Amompharetus - The leader of a battalion of Spartans, he refused to undertake the night-time retreat towards Plataea before the battle, since doing so would be shameful for a Spartan. Herodotus has a angry debate continuing between Pausanias and Amompharetus until dawn, whereupon the rest of the Spartan army finally began to retreat, leaving Amompharetus's division behind. Not expecting this, Amompharetus eventually led his men after the retreating Spartans. However, another tradition remembers Amompharetus as winning great renown at Plataea, and it has thus been suggested that Amompharetus, far from being insubordinate, had instead volunteered to guard the rear.

- Aristodemus - the lone Spartan survivor of the slaughter of the 300 at the Battle of Thermopylae, he had, with a fellow Spartiate, been dismissed from the army by Leonidas I because of an eye infection. However, his colleague had insisted on being led into battle, partially blind, by a helot. Preferring to return to Sparta, Aristodemus was branded a coward, and suffered a year of reproach before Plataea. Anxious to redeem his name, he charged the Persian lines by himself, killing in a savage fury before being killed. Although the Spartans agreed that he had redeemed himself, they awarded him no special honour, because he failed to fight in the disciplined manner expected of a Spartan.

- Callicrates - Considered the "most beautiful man, not among the Spartans only, but in the whole Greek camp" Callicrates was eager to distinguish himself that day as a warrior but was deprived of the chance by a stray arrow that pierced his side while standing in formation. When the battle commenced he insisted on making the charge with the rest but collapsed within a short distance. His last words, according to Herodotus, were "I grieve not because I have to die for my country, but because I have not lifted my arm against the enemy."

Aftermath

Main articles: Battle of Mycale and Second Persian invasion of Greece

According to Herodotus, the Battle of Mycale occurred on the same afternoon as Plataea. A Greek fleet under the Spartan king Leotychides had sailed to Samos to challenge the remnants of the Persian fleet. The Persians, whose ships were in a poor state of repair, had decided not to risk fighting, and instead drew their ships up on the beach at the feet of Mount Mycale in Ionia. An army of 60,000 men had been left there by Xerxes, and the fleet joined with them, building a pallisade around the camp to protect the ships. However, Leotychides decided to attack the camp with the Allied fleet's marines. Seeing the small size of the Greek force, the Persians emerged from the camp, but the Greek hoplites again proved superior, and destroyed much of the Persian force. The ships were abandoned to the Greeks, who burnt them, crippling Xerxes' sea power, and marking the ascendancy of the Greek fleet.

With the twin victories of Plataea and Mycale, the second Persian invasion of Greece was over. Moreover, the threat of future invasion was abated; although the Greeks remained worried that Xerxes would try again, over time it became apparent that the Persian desire to conquer Greece was much diminished.

The remnants of the Persian army, under the command of Artabazus, tried to retreat back to Asia Minor. Travelling through the lands of Thessaly, Macedon and Thrace by the shortest road, Artabazus eventually made it back to Byzantium, though losing many men to Thracian attacks, weariness and hunger. After the victory at Mycale, the Allied fleet sailed to the Hellespont to break down the pontoon bridges, but found that this was already done. The Peloponnesians sailed home, but the Athenians remained to attack the Chersonesos, still held by the Persians. The Persians in the region, and their allies, made for Sestos, the strongest town in the region, and the Athenians laid siege to them there. After a protracted siege, Sestos fell to the Athenians, marking the beginning of a new phase in the Greco-Persian Wars, the Greek counterattack. Herodotus ended his Histories after the Siege of Sestos. Over the next 30 years, the Greeks, primarily the Athenian-dominated Delian League, would expel (or help expel) the Persians from Macedon, Thrace, the Aegean islands and Ionia. Peace with Persia finally came in 449 BC with the Peace of Callias, finally ending the half-century of warfare.

Significance

Plataea and Mycale have great significance in Ancient history as the battles which decisively ended the second Persian invasion of Greece, thereby swinging the balance of the Greco-Persian Wars in favour of the Greeks. The Battle of Salamis saved Greece from immediate conquest, but it was Plataea and Mycale which effectively ended that threat. However, neither of these battles is nearly as well-known as Thermopylae, Salamis or Marathon. The reason for this discrepancy is not entirely clear; it might however be a result of the circumstances in which the battle was fought. The fame of Thermopylae certainly lies in the doomed heroism of the Greeks, in the face of overwhelming numbers; and Marathon and Salamis perhaps because they were both fought against the odds, and in dire strategic situations. Conversely, the Battles of Plataea and Mycale were both fought from a relative position of Greek strength, and against lesser odds; the Greeks in fact sought out battle on both occasions.

Militarily, the major lesson of both Plataea and Mycale (since both were fought on land) was to re-emphasise the superiority of the hoplite over the more-lightly armed Persian infantry, as had first been demonstrated at Marathon. Taking on this lesson, after the Greco-Persian Wars the Persian empire started recruiting and relying on Greek mercenaries.

Legacy

Monuments to the battle

Main article: Serpent ColumnA bronze column in the shape of intertwined snakes (the Serpent column) was created from melted-down Persian weapons, acquired in the plunder of the Persian camp, and was erected at Delphi. It commemorated all the Greek city-states that had participated in the battle, listing them on the column, and thus confirming some of Herodotus's claims. Most of it still survives in the Hippodrome of Constantinople (present-day Istanbul), where it was carried by Constantine the Great during the founding of his city on the Greek colony of Byzantium.

Sources

Main article: HerodotusThe main primary source for the Greco-Persian Wars is the Greek historian Herodotus. Herodotus, who has been called the 'Father of History', was born in 484 BC in Halicarnassus, Asia Minor (then under Persian overlordship). He wrote his "Enquiries" (Greek – Historia; English – (The) Histories) in around 440-430 BC, trying to trace the origins of the Greco-Persian Wars, which would still have been relatively recent history (the wars finally ending in 449 BC). Herodotus's approach was entirely novel, and at least in Western society, he does seem to have invented 'history' as we know it. As Holland has it:

"For the first time, a chronicler set himself to trace the origins of a conflict not to a past so remote so as to be utterly fabulous, nor to the whims and wishes of some god, nor to a people's claim to manifest destiny, but rather explanations he could verify personally."

Many subsequent ancient historians, despite following in his footsteps, derided Herodotus, starting with Thucydides. Nevertheless Thucydides chose to begin his history where Herodotus left off (at the Siege of Sestos), and must therefore have felt that Herodotus had done a reasonable job of summarising the preceding history. Plutarch criticised Herodotus in his essay "On The Malignity of Herodotus", describing Herodotus as "Philobarbaros" (barbarian-lover), for not being pro-Greek enough. This actually suggests that Herodotus might have done a reasonable job of being even-handed. A negative view of Herodotus was passed on Renaissance Europe, though he remained well read. However, since the 19th century his reputation has been dramatically rehabilitated by archaeological finds which have repeatedly confirmed his version of events. The prevailing modern view is perhaps that Herodotus generally did a remarkable job in his Historia, but that some of his specific details (particularly troop numbers and dates) should be viewed with skepticism. However, there are still some historians who believe Herodotus made up much of his story.

The Sicilian historian, Diodorus Siculus, writing in the 1st century BC in his Bibliotheca Historica, also provides an account of the Battle of Plataea. This account is fairly consistent with Herodotus's, but given that it was written much later, it may well have been derived from Herodotus's version. The Battle is also described in less detail by a number of other ancient historians including Plutarch, Ctesias of Cnidus, and is alluded by other authors, such as the playwright Aeschylus. Archaeological evidence, such as the Serpent Column also supports some of Herodotus's specific claims.

References

- ^ Holland, p47–55

- Holland, p203

- Herodotus V, 105

- ^ Holland, 171–178

- Herodotus VI, 44

- Herodotus VI, 101

- Herodotus VI, 113

- Holland, pp206–208

- Holland, pp208–211

- Herodotus VII, 32

- Herodotus VII, 145

- Holland, p226

- Holland, pp255-257

- Holland, pp292–294

- Herodotus VIII, 18

- Herodotus VIII, 21

- Herodotus VIII, 71

- Holland, p303

- ^ Holland, p333–335

- Herodotus VIII, 97

- Holland, pp327–329

- Holland, p330

- ^ Holland, pp336–338

- Herodotus IX, 7

- Herodotus IX, 6–9

- Herodotus IX, 10

- ^ Herodotus IX, 13

- Herodotus IX, 15

- ^ Herodotus IX, 28

- ^ Holland, pp343–349

- ^ Herodotus IX, 22

- Herodotus IX, 23

- ^ Herodotus, IX, 25

- Herodotus, IX, 33

- ^ Herodotus, IX, 39

- Herodotus IX, 49

- ^ Herodotus IX 51

- ^ Herodotus IX, 55 Cite error: The named reference "IX55" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Herodotus IX, 29

- Lazenby, p277

- Herodotus 9.30 IX, 30

- Herodotus VIII, 44

- Herodotus VII, 184

- ^ Lazenby, pp227–228

- ^ Holland, p400

- Herodotus VIII, 132

- Holland, p357

- Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca Historica XI, 29

- ^ Herodotus IX, 60

- ^ Herodotus IX, 32

- ^ Ctesias, Persica

- Holland, p237

- Connolly, p29

- Military History Online website

- Green, pp240–260

- ^ Delbrück, p35

- ^ Lazenby, pp217–219

- ^ Herodotus, IX, 41

- Lazenby, pp221–222

- ^ Herodotus, IX, 58 Cite error: The named reference "IX58" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- Lazenby, p254–257

- ^ Herodotus IX, 59

- ^ Holland, p350–355

- ^ Herodotus IX, 61

- ^ Herodotus IX, 62

- ^ Herodotus IX, 63

- ^ Herodotus IX, 65

- Herodotus IX, 64

- ^ Herodotus IX, 66

- ^ Herodotus IX, 67

- Herodotus IX, 68

- Herodotus IX, 69

- ^ Herodotus IX, 70

- Plutarch, Aristides 19

- Diodorus Siculus, Biblioteca Historica XI, 33

- Herodotus IX 53

- Herodotus IX, 56

- Herodotus IX 97

- Herodotus VII, 229

- Herodotus IX, 71

- Herodotus IX, 72

- ^ Herodotus IX, 96

- ^ Holland, pp357–358

- ^ Holland, p358–359

- Herodotus IX, 89

- ^ Herodotus IX, 114

- ^ Holland, pp359–363

- For instance, based on the number of Google hits, or the number of books written specifically about those battles

- ^ Holland, pp xvi–xxii Cite error: The named reference "hxvi" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- Xenophon, Anabasis

- Herodotus, IX, 81

- Note to Herodotus IX, 81

- Gibbon, chapters 17 and 68

- Cicero, On the Laws I, 5

- Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War, e.g. I, 22

- Holland, p xxiv

- David Pipes. "Herodotus: Father of History, Father of Lies". Retrieved 2008-01-18.

- ^ Holland, p377

- Fehling, pp1–277.

- Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca Historica, XI, 28–34

- Note to Herodotus IX, 81

Bibliography

- Herodotus, The Histories Perseus online version

- Ctesias, Persica (excerpt in Photius's epitome)

- Diodorus Siculus, Biblioteca Historica.

- Plutarch, Aristides

- Xenophon, Anabasis

- Delbrück, Hans. History of the Art of War Vol I

- Holland, Tom. Persian Fire. Abacus, 2005 (ISBN 978-0-349-11717-1)

- Green, Peter. The Greco-Persian Wars. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1970; revised ed., 1996 (hardcover, ISBN 0-520-20573-1); 1998 (paperback, ISBN 0-520-20313-5).

- Gibbon, Edward. The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire.

- Lazenby, JF. The Defence of Greece 490–479 BC. Aris & Phillips Ltd., 1993 (ISBN 0-85668-591-7)

- Fehling, D. Herodotus and His "Sources": Citation, Invention, and Narrative Art. Translated by J.G. Howie. Arca Classical and Medieval Texts, Papers, and Monographs, 21. Leeds: Francis Cairns, 1989

- Connolly, P. Greece and Rome at War, 1981

See also

- Greco-Persian Wars

- Second Persian invasion of Greece

- Battle of Thermopylae

- Battle of Artemisium

- Battle of Salamis

- Battle of Mycale

- Battle of Marathon

- Pausanias (general)

- Mardonius

External links

Categories: