This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Whispering (talk | contribs) at 09:27, 21 July 2009 (Reverted edits by 210.246.8.119 (talk) to last version by ClueBot). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 09:27, 21 July 2009 by Whispering (talk | contribs) (Reverted edits by 210.246.8.119 (talk) to last version by ClueBot)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| This article is part of a series on the | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History of the United States | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Timeline and periods

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Topics | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Groups | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Places

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The history of the United States from 1964 through 1980 includes the continuation of the African American Civil Rights Movement; the Vietnam War and protests against it; the continuation of the Cold War, with its competition to put a man on the Moon. This period is closed by the defeat of Jimmy Carter in his bid for re-election to the US presidency.

Civil rights

Main article: African-American Civil Rights Movement (1955-1968)The assassination of Kennedy in 1963 changed the political mood of the country. The new President, Lyndon B. Johnson, capitalized on this situation, using a combination of the national mood and his own political savvy to push Kennedy's agenda; most notably, the Civil Rights Act of 1964. In addition, the 1965 Voting Rights Act had an immediate impact on federal, state and local elections. Within months of its passage on August 6, 1965, one quarter of a million new black voters had been registered, one third by federal examiners. Within four years, voter registration in the South had more than doubled. In 1965, Mississippi had the highest black voter turnout — 74% — and led the nation in the number of black leaders elected. In 1969, Tennessee had a 92.1% voter turnout, Arkansas 77.9% and Texas 77.3%

Election of 1964

In the election of 1964, Lyndon Johnson positioned himself as a moderate, contrasting himself against his GOP opponent, Barry Goldwater, who the campaign characterized as hardline right-wing. Most famously, the Johnson campaign ran a commercial entitled the "Daisy Girl" ad, which featured a little girl picking petals from a daisy in a field, counting the petals, which then segues into a launch countdown and a nuclear explosion. The ads were a response to Goldwater's advocacy of using tactical nuclear weapons to combat communism in Asia.

Johnson soundly defeated Goldwater in the general election, winning 64.9% of the popular vote, the largest percentage differential since the 1824 election. However, Johnson's loss of support in southern states was evident and signified a reversal in electoral fortunes for Democrats who had depended on the "Solid South" as an electoral base.

Until the issue of civil rights divided conservative southern whites from the rest of the party, the political coalition of labor unions, minorities, liberals, and southern whites (the New Deal Coalition) had allowed the Democrats to control the federal government for nearly 30 years.

Further information: DixiecratAnti-poverty programs

Main articles: War on Poverty and Great SocietyMany federal assistance programs for individuals and families, including Medicare, which pays for many of the medical costs of the elderly, were begun in the 1960s during President Johnson's "War on Poverty." Although some of these programs encountered financial difficulties in the 1990s and various reforms were proposed, they continue to have strong support from both of the United States' major political parties. In addition, the Medicaid program finances medical care for low-income families.

During the 1960s the federal government provided food stamps to help poor families obtain food, and the federal and state governments jointly provided welfare grants to support low-income parents with children.

Counterculture

Main article: Counterculture of the 1960sAs the 1960s progressed, many young people began to revolt against the social norms and conservatism from the 1950s and early 1960s as well as the escalation of the Vietnam War and Cold War. In the mid 1960s, a social revolution swept through the country to create a more liberated society. As the Civil Rights Movement progressed, feminism and environmentalism movements soon grew as well as the Sexual Revolution. The Hippie culture, which emphasized peace, love and freedom, was introduced to the mainstream. In 1967, the Summer of Love, an event in San Francisco where thousands of young people loosely and freely united for a new social experience, helped introduce much of the world to the culture. In addition, the increase use of psychedelic drugs, such as LSD and marijuana, also became central to the movement. Music of the time also played a large role with the introduction of folk rock and later Acid Rock and Psychedelia which became the voice of the generation. The Counterculture Revolution was exemplified in 1969 with the historic Woodstock Festival.

Vietnam War

Main article: Vietnam WarU.S. involvement in the war gradually increased, though there never was a formal declaration of war. The U.S. Gulf of Tonkin Resolution in 1964 gave broad Congressional support to President Johnson to escalate U.S. involvement in the war. U.S. troop deployments and casualties steadily increased after this point. At first, the U.S. public largely supported the war, but the NLF-led 1968 Tet Offensive in South Vietnam shattered much of that support. While U.S. and ARVN military operations managed to successfully reduce the Viet Cong to a state of ineffectiveness, waning public support in the U.S. led to troop withdrawals and increased "Vietnamization" of the war effort in the south.

Antiwar movement

Main article: Opposition to the Vietnam War

Starting in 1964, a small antiwar movement began on college campuses. Some opposed the war on moral grounds, while others felt the war lacked clear objectives or a clear exit strategy. Opposition to the war occurred during a heightened time of student activism, coinciding with the arrival at college age of the demographically significant "baby boomers." World War II ended in 1945, and the Korean conflict ended in 1953; thus most, if not all, baby boomers had never been exposed to war.

The Vietnam War was unprecedented for the intensity of media coverage—it has been called the first television war—as well as for the stridency of opposition to the war by the "New Left."

The divide between pro- and anti-war Americans continued long after the conclusion of the war and became another factor leading to the "culture wars" that increasingly divides Americans, continuing into the 21st century.

Election of 1968

In 1968, President Lyndon Johnson began his reelection campaign. A member of his own Democratic party, Eugene McCarthy, ran against him for the nomination on an antiwar platform. McCarthy did not win the first primary election in New Hampshire, but he did surprisingly well against an incumbent. The resulting blow to the Johnson campaign, taken together with other factors, led the President to make a surprise announcement in a March televised speech that he was pulling out of the race. He also announced the initiation of peace talks in Paris with Vietnam.

Seizing the opportunity caused by Johnson's departure from the race, Robert Kennedy then joined in and ran for the nomination on an antiwar platform. Vice President Hubert Humphrey also ran for the nomination, promising to continue to support the South Vietnamese government.

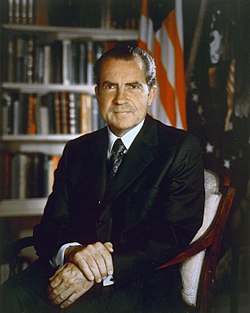

Robert Kennedy was assassinated that summer, and McCarthy was unable to overcome Humphrey's support within the party elite. Humphrey won the nomination of his party and ran against Republican Richard Nixon in the general election. Nixon appealed to what he claimed was the "silent majority" of moderate Americans who disliked the "hippie" counterculture. Nixon also promised "peace with honor" by his "secret plan" to end the Vietnam War. He proposed the Nixon Doctrine to establish the strategy to turn over the fighting of the war to the Vietnamese, which he called "Vietnamization." Nixon won the presidency, against the divided opposition.

Withdrawal

Nixon discovered that withdrawing from Vietnam, though popular, was much more easily promised than done. Attempting to balance concerns for South Vietnam's ability to defend itself alone, with the increasing pressure from the United States Congress to get the troops out, as well as the legislature's inclination to unilaterally reduce and finally cut off funding for the war, Nixon was forced to expend great amounts of effort and political capital.

At the same time, he became a lightning rod for much public hostility regarding the war in Vietnam. The morality of conflict continued to be an issue, and incidents such as the My Lai massacre further eroded support for the war and increased efforts of Vietnamization.

The growing Watergate scandal was also a major distraction for Nixon, Further, what little monetary support for South Vietnam that was provided by the U.S. Congress was siphoned off by corrupt South Vietnamese government and military officials.

The United States finally withdrew its troops from Vietnam following the Paris Peace Accords in 1973. However, some back-up troops remained until two years later, exiting with the collapse of Saigon and the North gaining complete control of the country, effectively ending the Vietnam War on April 30, 1975.

In the end, around 1.5 million Vietnamese were killed in the war, and around 58,000 U.S. soldiers died. Casualties inflicted by the Khmer Rouge in adjacent Cambodia were even higher. Some state that the destabilization of the Vietnam War and the distractive cover of that conflict allowed the murderous Khmer Rouge to flourish.

"Stagflation"

At the same time that President Johnson persuaded Congress to accept a tax cut in 1964, he was rapidly increasing spending for both domestic programs and for the war in Vietnam. The result was a major expansion of the money supply, resting largely on government deficits, which pushed prices rapidly upward. However, inflation also rested on the nation's steadily declining supremacy in international trade and, moreover, the decline in the global economic, geopolitical, commercial, technological, and cultural preponderance of the United States since the end of World War II. After 1945, the U.S. enjoyed easy access to raw materials and substantial markets for its goods abroad; the U.S. was responsible for around a third of the world's industrial output because of the devastation of postwar Europe. By the 1960s, not only were the industrialized nations now competing for increasingly scarce raw commodities, but Third World suppliers were increasingly demanding higher prices. The automobile and steel industries were also beginning to face stiff competition in the U.S. domestic market by foreign producers.

Nixon promised to tackle sluggish growth and inflation, known as "stagflation," through higher taxes and lower spending; this met stiff resistance in Congress. As a result, Nixon changed course and opted to control the currency; his appointees to the Federal Reserve sought a contraction of the money supply through higher interest rates but to little avail; the tight money policy did little to curb inflation. The cost of living rose a cumulative 15% during Nixon's first two years in office.

By the summer of 1971, Nixon was under strong public pressure to act decisively to reverse the economic tide. On August 15, 1971, he ended the convertibility of the U.S. dollar into gold, which meant the demise of the Bretton Woods system, in place since World War II. As a result, the U.S. dollar fell in world markets. The devaluation helped stimulate American exports, but it also made the purchase of vital inputs, raw materials, and finished goods from abroad more expensive. Also, on August 15, 1971, under the provisions of the Economic Stabilization Act of 1970, Nixon implemented "Phase I" of his economic plan: a ninety-day freeze on all wages and prices above their existing levels. In November, "Phase II" entailed mandatory guidelines for wage and price increases to be issued by a federal agency. Inflation subsided temporarily, but the recession continued with rising unemployment. To combat the recession, Nixon reversed course and adopted an expansionary monetary and fiscal policy. In "Phase III", the strict wage and price controls were lifted. As a result, inflation resumed its upward spiral.

Inflationary pressures led to key shifts in economic policies. Following the Great Depression of the 1930s, recessions—periods of slow economic growth and high unemployment—were viewed as the greatest of economic threats, which could be counteracted by heavy government spending or cutting taxes so that consumers would spend more. In the 1970s, major price increases, particularly for energy, created a strong fear of inflation; as a result, government leaders concentrated more on controlling inflation than on combating recession by limiting spending, resisting tax cuts, and reining in growth in the money supply.

The erratic economic programs of the Nixon administration were indicative of a broader national confusion about the prospects for future American prosperity. With little understanding of the international forces creating the economic problems, Nixon, American economists, and the public focused on immediate issues and short-term solutions. These underlying problems set the stage for conservative reaction, a more aggressive foreign policy, and a retreat from welfare-based solutions for minorities and the poor that would characterize the subsequent decades.

1973 oil crisis

Main article: 1973 oil crisis

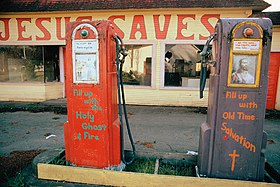

To make matters worse, the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) began displaying its strength; oil, fueling automobiles and homes in a country increasingly dominated by suburbs (where large homes and automobile-ownership are more common), became an economic and political tool for Third World nations to begin fighting for their concerns. Following the 1973 Yom Kippur War, Arab members of OPEC announced they would no longer ship petroleum to nations supporting Israel, that is, to the United States and Western Europe. At the same time, other OPEC nations agreed to raise their prices 400%. This resulted in the 1973 world oil shock, during which U.S. motorists faced long lines at gas stations. Public and private facilities closed down to save on heating oil; and factories cut production and laid off workers. No single factor than the oil embargo did more to produce the soaring inflation of the 1970s.

The U.S. government response to the embargo was quick but of limited effectiveness. A national maximum speed limit of 55 mph (88 km/h) was imposed to help reduce consumption. President Nixon named William Simon as an official "energy czar," and in 1977, a cabinet-level Department of Energy was created, leading to the creation of the United States' Strategic Petroleum Reserve. The National Energy Act of 1978 was also a response to this crisis.

The federal government further exacerbated the recession by instilling price controls in the United States, which limited the price of "old oil" (that already discovered) while allowing newly discovered oil to be sold at a higher price, resulting in a withdrawal of old oil from the market and artificial scarcity. The rule had been intended to promote oil exploration. This scarcity was dealt with by rationing of gasoline (which occurred in many countries), with motorists facing long lines at gas stations.

In the U.S., drivers of vehicles with license plates having an odd number as the last digit (or a vanity license plate) were allowed to purchase gasoline for their cars only on odd-numbered days of the month, while drivers of vehicles with even-numbered license plates were allowed to purchase fuel only on even-numbered days. The rule did not apply on the 31st day of those months containing 31 days. In some U.S. states, a three color flag system was use to denote gasoline availability at service stations. A green flag denoted unrationed sale of gasoline. A yellow flag denoted restricted and rationed sales. A red flag denoted that no gasoline was available at the service station, but it was open for other services.

Year-round Daylight Saving Time was implemented: at 2:00 a.m. local time on January 6, 1974, clocks were advanced one hour across the nation. The move spawned significant criticism because it forced many children to commute to school before sunrise. As a result, the clocks were turned back on the last Sunday in October as originally scheduled, and in 1975 clocks were set forward one hour at 2:00 a.m. on February 23, the later date being adopted to address the aforementioned issue. The pre-existing daylight-saving rules, calling for the clocks to be advanced one hour on the last Sunday in April, were restored in 1976.

The crisis also prompted a call for individuals and businesses to conserve energy — most notably a campaign by the Advertising Council using the tag line "Don't Be Fuelish." Many newspapers carried full-page advertisements that featured cut-outs which could be attached to light switches that had the slogan "Last Out, Lights Out: Don't Be Fuelish" emblazoned thereon.

The U.S. "Big Three" automakers' first order of business after Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standards were enacted was to downsize existing automobile categories. By the end of the 1970s, 121-inch wheelbase vehicles with a 4,500 pound GVW (gross weight) were a thing of the past. Before the mass production of automatic overdrive transmissions and electronic fuel injection, the traditional front engine/rear wheel drive layout was being phased out for the more efficient and/or integrated front engine/front wheel drive, starting with compact cars. Using the Volkswagen Rabbit as the archetype, much of Detroit went to front wheel drive after 1980 in response to CAFE's 27.5 mpg mandate. Vehicles such as the Ford Fairmont were short-lived in the early 1980s. Though not required by legislation, the sport of auto racing voluntarily sought reductions. The 24 Hours of Daytona was canceled in 1974. Also in 1974, NASCAR reduced all race distances by 10%. At the Indianapolis 500, qualifying was reduced from four days down to two, and several days of practice were eliminated.

Détente with USSR

Main articles: SALT I and DétenteIn 1972-1973, the superpowers sought each other's help. After making a surprise trip to China, President Nixon signed the SALT I treaty with Leonid Brezhnev to limit the development of strategic weapons.

Détente had both strategic and economic benefits for both superpowers. Arms control enabled both superpowers to slow the spiraling increases in their bloated defense budgets. Before, the Johnson Administration failed to defeat Communist forces, his deficit-spending to sustain the war effort weakened the U.S. economy for decades to come, contributing to a decade of "stagflation." Meanwhile, the Soviets could neither stop bloody clashes between Soviet and Chinese troops along their common border nor bolster a Soviet economy declining, in part, because of heavy military expenditures. They also agreed to respect the newly emerging states in Africa and Asia.

But the détente suffered amid outbreaks in the Middle East and Africa, especially southern and eastern Africa. The two nations continued to compete with each other for influence in the resource-rich Third World, most notably in Chile.

Most Americans believed claims that the Cold War was a struggle of the free world against totalitarianism. However, the United States targeted for overthrow, as it did in the 1950s, governments which were perceived as Marxist, even in cases when they had been elected, such as Chile's socialist president Salvador Allende.

Communistic and socialistic values often conflicted with America's capitalistic approach. Communist and socialist countries were less likely to trade and use their general populations as cheap labor for the gain of a wealthy minority. As labor laws increased and immigration slowed, America was becoming more dependent on cheap labor from weaker developing nations.

Watergate

In 1972, Nixon won the GOP nomination and faced Democratic nominee George McGovern, who ran on a platform of ending the Vietnam War and instituting guaranteed minimum incomes for the nation's poor. Between difficulties with his running-mate, Thomas Eagleton (who he eventually dropped and replaced with Sargent Shriver), and the Republicans' successful campaign to paint him as unacceptably radical, he suffered a 61% - 38% defeat to sitting President Richard Nixon.

Nixon was investigated for the instigation and cover-up of the burglary of the Democratic Party offices at the Watergate office complex. The House of Representatives Judiciary Committee opened formal and public impeachment hearings against Nixon on May 9, 1974. Rather than face impeachment by the House of Representatives and a possible conviction by the Senate, he resigned, effective August 9, 1974. His successor, Gerald R. Ford, a moderate Republican, issued a pre-emptive pardon of Nixon, ending the investigations of him.

Carter Administration

Main articles: U.S. presidential election, 1976 and Jimmy CarterThe Watergate scandal was still fresh in the voters' minds when former Georgia Governor Jimmy Carter, a Washington, DC outsider known for his integrity, prevailed over nationally better-known politicians in the Democratic Party Presidential primaries in 1976. Carter became the first candidate from the Deep South to be elected President since the American Civil War.

His administration is perhaps best known for failing to free the hostages in Tehran, an economic and energy crisis, and for helping to establish a peace treaty between Israel and Egypt.

Carter also tried to place another cap on the arms race with a SALT II agreement in 1979, and faced the Islamic Revolution in Iran, the Nicaraguan Revolution, and the Soviet Invasion of Afghanistan.

In 1979, Carter allowed the former Iranian Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi into the United States for political asylum and medical treatment. Although Carter had ostensibly promoted human rights as a hallmark of his foreign policy, he continued U.S. support of the Iranian strongman during his reign. In response to the Shah's entry into the U.S., Iranian militants seized the American embassy in Iranian hostage crisis, taking 52 Americans hostage and demanded the Shah's return to Iran for trial and execution. Despite the Shah's death in Egypt, the hostage crisis continued and dominated the last year of Carter's presidency. The subsequent responses to the crisis, from a "Rose Garden strategy" of staying inside the White House to the botched attempt to rescue the hostages, did not inspire confidence in the Administration by the American people.

In 1979, Carter gave a nationally televised address in which he identified what he believed to be a crisis of confidence among the American people. This has come to be known as his "malaise" speech, even though he did not actually use the word. Rather than inspiring Americans to action as he had hoped, the speech likely damaged his reelection hopes because it was perceived by many to express a pessimistic outlook and seemed in many ways as if Carter was literally blaming the American people for his own failed policies.

References

| This article does not cite any sources. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "History of the United States" 1964–1980 – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (April 2009) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| History of the United States | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||