This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Sjö (talk | contribs) at 11:03, 13 August 2009 (Reverted edits by 82.171.254.158 (talk) to last version by Sjö). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 11:03, 13 August 2009 by Sjö (talk | contribs) (Reverted edits by 82.171.254.158 (talk) to last version by Sjö)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) See also: Puntland

The Land of Punt, also called Pwenet, or Pwene by the ancient Egyptians, was a trading partner known for producing and exporting gold, aromatic resins, African blackwood, ebony, ivory, slaves and wild animals. Information about Punt has been found in ancient Egyptian records of trade missions to this region.

At times it is synonymous with Ta netjer, the "land of the god".

The exact location of Punt remains a mystery. The mainstream view is that Punt was located to the south-east of Egypt, most likely on the coast of the Horn of Africa. However some scholars point instead to a range of ancient inscriptions which locate Punt in Arabia.

Egyptian expeditions to Punt

The earliest recorded Egyptian expedition to Punt was organized by Pharaoh Sahure of the Fifth Dynasty (25th century BC) although gold from Punt is recorded as having been in Egypt in the time of king Khufu of the Fourth Dynasty of Egypt.

Subsequently, there were more expeditions to Punt in the Sixth Dynasty of Egypt, the Eleventh dynasty of Egypt, the Twelfth dynasty of Egypt and the Eighteenth dynasty of Egypt. In the Twelfth dynasty of Egypt, trade with Punt was celebrated in popular literature in "The Tale of the Shipwrecked Sailor"

In the reign of Mentuhotep III (around 1950 BC), an officer named Hannu organized one or more voyages to Punt, but it is uncertain whether he traveled on these expeditions. Trading missions of the 12th dynasty pharaohs Senusret I and Amenemhat II had also successfully navigated their way to and from the mysterious land of Punt.

In the Eighteenth dynasty of Egypt, Hatshepsut built a Red Sea fleet to facilitate trade between the head of the Gulf of Aqaba and points south as far as Punt to bring mortuary goods to Karnak in exchange for Nubian gold. Hatshepsut personally made the most famous ancient Egyptian expedition that sailed to Punt. During the reign of Queen Hatshepsut in the 15th century BC ships regularly crossed the red Sea in order to obtain bitumen, copper, carved amulets, naptha and other goods transported overland and down the dead sea to Elat at the head of the gulf of Aqaba where they were joined with Frankincense and myrrh coming north both by sea and overland along trade routes through the mountains running north along the east coast of the Red Sea.

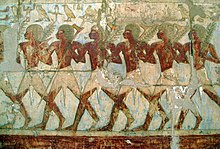

A report of that 5 ship voyage survives on reliefs in Hatshepsut's mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahri. Throughout the temple texts, Hatshepsut "maintains the fiction that her envoy" Chancellor Nehsi, who is mentioned as the head of the expedition, had travelled to Punt "in order to extract tribute from the natives" who admit their allegiance to the Egyptian pharaoh. In reality, Nehsi's expedition was a simple trading mission to a land, Punt, which was by this time a well-established trading post. Moreover, Nehsi's visit to Punt was not inordinately brave since he was "accompanied by at least five shiploads of marines" and greeted warmly by the chief of Punt and his immediate family. The Puntites "traded not only in their own produce of incense, ebony and short-horned cattle, but in goods from other African states including gold, ivory and animal skins." According to the temple reliefs, the Land of Punt was ruled at that time by King Parahu and Queen Ati. This well illustrated expedition of Hatshepsut occurred in Year 9 of the female pharaoh's reign with the blessing of the god Amun:

Said by Amen, the Lord of the Thrones of the Two Land: 'Come, come in peace my daughter, the graceful, who art in my heart, King Maatkare ...I will give thee Punt, the whole of it...I will lead your soldiers by land and by water, on mysterious shores, which join the harbours of incense...They will take incense as much as they like. They will load their ships to the satisfaction of their hearts with trees of green incense, and all the good things of the land.'

While the Egyptians "were not particularly well versed in the hazards of sea travel, and the long voyage to Punt, must have seemed something akin to a journey to the moon for present-day explorers...the rewards of clearly outweighted the risks." Hatshepsut's 18th dynasty successors, such as Thutmose III and Amenhotep III also continued the Egyptian tradition of trading with Punt. The trade with Punt continued into the start of the 20th dynasty before terminating prior to the end of Egypt's New Kingdom. Papyrus Harris I, a contemporary Egyptian document which detailed events that occurred in the reign of the early 20th dynasty king Ramesses III, includes an explicit description of an Egyptian expedition's return from Punt:

They arrived safely at the desert-country of Coptos: they moored in peace, carrying the goods they had brought. They were loaded, in travelling overland, upon asses and upon men, being reloaded into vessels at the harbour of Coptos. They were sent forward downstream, arriving in festivity, bringing tribute into the royal presence.

After the end of the New Kingdom period, Punt became "an unreal and fabulous land of myths and legends."

Ta netjer

The ancient Egyptians also called Punt Ta netjer, meaning "God's Land". This did not mean they considered Punt a "Holy Land"; rather, it meant the regions of the Sun God, i.e., regions located in the direction of the sunrise. These eastern regions were blessed with precious products, such as incense, used in temples. The term was used not only about Punt, located southeast of Egypt, but also about regions of Asia east and northeast of Egypt, such as Lebanon, which was the source of wood for temples.

Location

The ancient Egyptians viewed the Land of Punt (Pun.t; Pwenet; Pwene) as their ancestral homeland. In his book “The Making of Egypt” (1939), W. M. Flinders Petrie stated that the Land of Punt was “sacred to the Egyptians as the source of their race.” E.A. Wallis Budge stated that “Egyptian tradition of the Dynastic Period held that the aboriginal home of the Egyptians was Punt…”

The exact location of Punt remains a mystery. The mainstream view is that Punt was located to the south-east of Egypt, most likely in the Horn of Africa.

However some scholars disagree with this view and point to a range of ancient inscriptions which locate Punt in Arabia. Dimitri Meeks has written that “Texts locating Punt beyond doubt to the south are in the minority, but they are the only ones cited in the current consensus about the location of the country. Punt, we are told by the Egyptians, is situated – in relation to the Nile Valley – both to the north, in contact with the countries of the Near East of the Mediterranean area, and also to the east or south-east, while its furthest borders are far away to the south. Only the Arabian Peninsula satisfies all these indications.”

The placement of Punt in Eastern Africa is based on the fact that the products of Punt were abundantly found in East Africa but were less common or absent in Arabia. These products included gold, aromatic resins such as myrrh, ebony and elephant tusks. The wild animals depicted in Punt include giraffes, baboons, hippopotami and leopards which were common in East Africa but are less frequent or completely absent in Arabia. Says Richard Pankhurst, in his book “The Ethiopians”: “ has been identified with territory on both the Arabian and African coasts. Consideration of the articles which the Egyptians obtained from Punt, notably gold and ivory, suggests, however, that these were primarily of African origin. … This leads us to suppose that the term Punt probably applied more to African than Arabian territory.”

In 2003 a newly discovered text was found in a tomb in El Kab, a small town that is located about 50 kilometres south of Thebes. The tomb belonged to the local governor, Sobeknakht II, and dates to the 17th dynasty (c.1600-1550 BC). An article in the Al-Ahram newspaper reported that the inscription mentions “a huge attack from the south on Elkab and Egypt by the Kingdom of Kush and its allies from the land of Punt.” A similar article in the Times reports that "the inscription describes a ferocious invasion of Egypt by armies from Kush and its allies from the south, including the land of Punt..."

Encyclopaedia Britannica describes Punt as follows: “in ancient Egyptian and Greek geography, the southern coast of the Red Sea and adjacent coasts of the Gulf of Aden, corresponding to modern coastal Eritrea and Djibouti.”

The consensus view among the majority of Egyptologists is summed up by Ian Shaw from the Oxford History of Ancient Egypt:

There is still some debate regarding the precise location of Punt, which was once identified with the region of modern Somalia. A strong argument has now been made for its location in either southern Sudan or the Eritrea, where the indigenous plants and animals equate most closely with those depicted in the Egyptian reliefs and paintings.

Notes

- Ian Shaw & Paul Nicholson, The Dictionary of Ancient Egypt, British Museum Press, London. 1995, p.231.

- Shaw & Nicholson, p.231.

- Breasted, John Henry (1906-1907), Ancient Records of Egypt: Historical Documents from the Earliest Times to the Persian Conquest, collected, edited, and translated, with Commentary, p.433, vol.1

- Breasted & 1906-07, p. 161, vol. 1.

- Breasted & 1906-07, p. 427-433, vol. 1.

- Joyce Tyldesley, Hatchepsut: The Female Pharaoh, Penguin Books, 1996 hardback, p.145

- Dr. Muhammed Abdul Nayeem, (1990). Prehistory and Protohistory of the Arabian Peninsula. Hyderabad. ISBN.

- Tyldesley, Hatchepsut, p.149

- Tyldesley, Hatchepsut, p.147

- Tyldesley, Hatchepsut, p.147

- Tyldesley, Hatchepsut, pp.147 & 149

- Tyldesley, Hatchepsut, p.147

- Breasted & 1906-07, p. 246-295, vol. 1.

- E. Naville, The Life and Monuments of the Queen in T.M. Davis (ed.), the tomb of Hatshopsitu, London: 1906. pp.28-29

- Tyldesley, Hatchepsut, pp.145 & 148

- Tyldesley, Hatchepsut, pp.145-46

- Tyldesley, Hatchepsut, pp.145-146

- K.A. Kitchen, Punt and how to get there, Orientalia 40 (1971), 184-207:190.

- Tyldesley, Hatchepsut, p.146

- Breasted & 1906-07, p. 658, vol. II.

- Breasted & 1906-07, p. 451,773,820,888, vol. II.

- Ethiopia.

- A short history of the Egyptian people.

- White, Jon Manchip., Ancient Egypt: Its Culture and History (Dover Publications; New Ed edition, June 1, 1970), p. 141. "It may be noted that the ancient Egyptians themselves appear to have been convinced that their place of origin was African rather than Asian. They made continued reference to the land of Punt as their homeland."

- Short History of the Egyptian People, by E. A. Wallis Budge

- Dimitri Meeks - Chapter 4 - “Locating Punt” from the book “Mysterious Lands”, by David B. O'Connor and Stephen Quirke.

- http://books.google.com/books?id=jcpQqkHr328C&printsec=frontcover#PPA13,M1

- Hatshepsut's Temple at Deir El Bahari By Frederick Monderson

- Shaw & Nicholson, p.231.

- Tyldesley, Hatchepsut, p.147

- http://weekly.ahram.org.eg/2003/649/he1.htm

- Ancient Egypt's Humiliating Secret

- http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/483652/Punt

- The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt, Ian Shaw, p. 317, 2003

References

- Bradbury, Louise (1988), "Reflections on Travelling to 'God's Land' and Punt in the Middle Kingdom", Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt, 25: 127–156.

- Breasted, John Henry (1906-1907), Ancient Records of Egypt: Historical Documents from the Earliest Times to the Persian Conquest, collected, edited, and translated, with Commentary, vol. 1–5, University of Chicago Press

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: date and year (link). - Fattovich, Rodolfo. 1991. "The Problem of Punt in the Light of the Recent Field Work in the Eastern Sudan". In Akten des vierten internationalen Ägyptologen Kongresses, München 1985, edited by Sylvia Schoske. Vol. 4 of 4 vols. Hamburg: Helmut Buske Verlag. 257–272.

- ———. 1993. "Punt: The Archaeological Perspective". In Sesto congresso internazionale de egittologia: Atti, edited by Gian Maria Zaccone and Tomaso Ricardi di Netro. Vol. 2 of 2 vols. Torino: Italgas. 399–405.

- Herzog, Rolf. 1968. Punt. Abhandlungen des Deutsches Archäologischen Instituts Kairo, Ägyptische Reihe 6. Glückstadt: Verlag J. J. Augustin.

- Kitchen, Kenneth (1971), "Punt and How to Get There", Orientalia, 40: 184–207

- Kitchen, Kenneth (1993), "The Land of Punt", in Shaw, Thurstan; Sinclair, Paul; Andah, Bassey; Okpoko, Alex (eds.), The Archaeology of Africa: Foods, Metals, Towns, vol. 20, London and New York: Routledge, pp. 587–608.

- Meeks, Dimitri (2003), "Locating Punt", in O'Connor, David B.; Quirke, Stephen G. J. (eds.), Mysterious Lands, Encounters with ancient Egypt, vol. 5, London: Institute of Archaeology, University College London, University College London Press, pp. 53–80, ISBN 1-84472-004-7.

- Paice, Patricia (1992), "The Punt Relief, the Pithom Stela, and the Periplus of the Erythean Sea", in Harrak, Amir (ed.), Contacts Between Cultures: Selected Papers from the 33rd International Congress of Asian and North African Studies, Toronto, August 15-25, 1990, vol. 1, Lewiston, Queenston, and Lampeter: The Edwin Mellon Press, pp. 227–235.

Older literature

- Johannes Dumichen: Die Flotte einer ägyptischen Königin, Leipzig, 1868.

- Wilhelm Max Müller: Asien und Europa nach altägyptischen Denkmälern, Leipzig, 1893.

- Adolf Erman: Life in Ancient Egypt, London, 1894.

- Édouard Naville: "Deir-el-Bahri" in Egypt Exploration Fund, Memoirs XII, XIII, XIV, and XIX, London, 1894 et seq.

- James Henry Breasted: A History of the Ancient Egyptians, New York, 1908.

External links

- The Wonderful Land of Punt

- The Land of Punt with quotes from Breasted (1906) and Petrie (1939)

- Queen Hatasu, and Her Expedition to the Land of Punt by Amelia Ann Blanford Edwards (1891)

- Deir el-Bahri: Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut

- Hall of Punt at Deir el-Bahri; and Where was Punt? discussion by Dr. Karl H. Leser

- Queen of Punt syndrome

News reports on Wadi Gawasis excavations

- Archaeologists discover ancient ships in Egypt (Boston University Bridge, 18 March 2005). Excavations at Wadi Gawasis, possibly the ancient Egyptian port Saaw.

- Remains of ancient Egyptian seafaring ships discovered (New Scientist, 23 March 2005).

- Egyptian sea vessel artifacts discovered at pharaonic port of Mersa Gawasis along Red Sea coast (EurekAlert, 21 April 2005).

- University professor finds ancient shipwreck (Boston University Daily Free Press, 27 April 2005).

- Ancient Mariners: Caves harbor view of early Egyptian sailors (Science News Online, 7 May 2005).

- Sailing to distant lands (Al Ahram, 2 June 2005).

- Ancient ship remains are unearthed (Deutsche Press Agentur, 26 January 2006).

- 4,000-year-old shipyard unearthed in Egypt (MSNBC, 6 March 2006).