This is an old revision of this page, as edited by 118.90.120.177 (talk) at 10:12, 12 September 2009 (→History). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 10:12, 12 September 2009 by 118.90.120.177 (talk) (→History)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) "Shinobi" redirects here. For other uses, see Shinobi (disambiguation). For other uses, see Ninja (disambiguation).

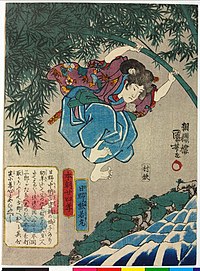

A ninja or shinobi (忍者) was a covert agent or mercenary of feudal Japan specializing in unorthodox arts of war. The functions of the ninja included espionage, sabotage, infiltration, assassination, as well as open combat in certain situations. The underhanded tactics of the ninja were contrasted with the samurai, who were careful not to tarnish their reputable image.

In his Buke Myōmokushō, military historian Hanawa Hokinoichi writes of the ninja:

They travelled in disguise to other territories to judge the situation of the enemy, they would inveigle their way into the midst of the enemy to discover gaps, and enter enemy castles to set them on fire, and carried out assassinations, arriving in secret.

The origin of the ninja is obscure and difficult to determine, but can be surmised to be around the 14th century. Few written records exist to detail the activities of the ninja. The word shinobi did not exist to describe a ninja-like agent until the 15th century, and it is unlikely that spies and mercenaries prior to this time were seen as a specialized group. In the unrest of the Sengoku period (15th - 17th centuries), mercenaries and spies for hire arose out of the Iga and Kōga regions of Japan, and it is from these clans that much of later knowledge regarding the ninja is inferred. Following the unification of Japan under the Tokugawa shogunate, the ninja descended again into obscurity. However, in the 17th and 18th centuries, manuals such as the Bansenshukai (1676) — often centered around Chinese military philosophy — appeared in significant numbers. These writings revealed an assortment of philosophies, religious beliefs, their application in warfare, as well as the espionage techniques that form the basis of the ninja's art. The word ninjutsu would later come to describe a wide variety of practices related to the ninja.

The mysterious nature of the ninja has long captured popular imagination in Japan, and later the rest of the world. Ninjas figure prominently in folklore and legend, and as a result it is often difficult to separate historical fact from myth. Some legendary abilities include invisibility, walking on water, and control over natural elements. The ninja is also prevalent in popular culture, appearing in many forms of entertainment media.

Etymology

Ninja is the on'yomi reading of the two kanji "忍者". In the native kun'yomi reading, it is read shinobi, a shortened form of the longer transcription shinobi-no-mono (忍の者). The term shinobi has been traced as far back as the late 8th century to poems in the Man'yōshū. The underlying connotation of shinobi (忍) means "to steal away" and — by extension — "to forbear", hence its association with stealth and invisibility. Mono (者) means "a person".

Historically, the word ninja was not in common use, and a variety of regional colloquialisms evolved to describe what would later be dubbed ninjas. Along with shinobi, some examples include monomi ("one who sees"), nokizaru ("macaque on the roof"), rappa ("ruffian"), kusa ("grass") and Iga-mono ("one from Iga"). In historical documents, shinobi is almost always used.

Kunoichi, meaning a female ninja, supposedly came from the characters くノ一 (pronounced 'ku', 'no' and 'ichi'), which make up the three strokes that form the kanji for "woman" (女).

In the West, the word ninja became more prevalent than shinobi in the post-World War II culture, possibly because it was more comfortable for Western speakers. In English, the plural of ninja can be either unchanged as ninja, reflecting the Japanese language's lack of grammatical number, or the regular English plural ninjas.

History

they had SEX Yeah Babby !!!!!!!!

Roles

The ninja were stealth soldiers and mercenaries hired mostly by daimyos. Their primary roles were those of espionage and sabotage, although assassinations were also attributed to ninjas. In battle, the ninja could also be used to cause confusion amongst the enemy. A degree of psychological warfare in the capturing of enemy banners can be seen illustrated in the Ōu Eikei Gunki, composed between the 16th and 17th centuries:

"Within Hataya castle there was a glorious shinobi whose skill was renowned, and one night he entered the enemy camp secretly. He took the flag from Naoe Kanetsugu's guard ...and returned and stood it on a high place on the front gate of the castle."

Espionage

Espionage was the chief role of the ninja. With the aid of disguises, the ninja gathered information on enemy terrain, building specifications, as well as obtaining passwords and communiques. The aforementioned supplement to the Nochi Kagami briefly describes the ninja's role in espionage:

"Concerning ninja, they were said to be from Iga and Kōga, and went freely into enemy castles in secret. They observed hidden things, and were taken as being friends"

Later in history, the Kōga ninja would become regarded as agents of the Tokugawa bakufu, at a time when the bakufu used the ninjas in an intelligence network to monitor regional daimyos as well as the Imperial court.

Sabotage

Arson was the primary form of sabotage practiced by the ninja, who targeted castles and camps.

The 16th century diary of abbot Eishun (Tamon-in Nikki) at Tamon-in monastery in Kōfuku-ji describes an arson attack on a castle by men of the Iga clans.

"This morning, the sixth day of the 11th month of Tembun 10, the Iga-shu entered Kasagi castle in secret and set fire to a few of the priests' quarters. They also set fire to outbuildings in various places inside the San-no-maru. They captured the Ichi-no-maru (inner bailey) and the Ni-no-maru."

— Entry: 26th day of the 11th month of the 10th Year of Tenbun (1541)

In 1558, Rokkaku Yoshitaka employed a team of ninja to set fire to Sawayama Castle. A chunin captain led a force of forty-eight ninja into the castle by means of deception. In a technique dubbed bakemono-jutsu ("ghost technique"), his men stole a lantern bearing the enemy's family crest (mon), and proceeded to make replicas with the same mon. By wielding these lanterns, they were allowed to enter the castle without a fight. Once inside, the ninjas set fire to the castle, and Yoshitaka's army would later emerge victorious. The mercenary nature of the shinobi is demonstrated in another arson attack soon after the burning of Sawayama Castle. In 1561, commanders acting under Kizawa Nagamasa hired three Iga ninja of genin rank to assist the conquest of a fortress in Maibara. Rokakku Yoshitaka, the same man who had hired Iga ninja just years earlier, was the fortress holder — and target of attack. The Asai Sandaiki writes of their plans: "We employed shinobi-no-mono of Iga. ...They were contracted to set fire to the castle". However, the mercenary shinobi were unwilling to take commands. When the fire attack did not begin as scheduled, the Iga men told the commanders, who were not from the region, that they could not possibly understand the tactics of the shinobi. They then threatened to abandon the operation if they were not allowed to act on their own strategy. The fire was eventually set, allowing Nagamasa's army to capture the fortress in a chaotic rush.

Assassination

The most well-known cases of assassination attempts involve famous historical figures. Deaths of famous persons have sometimes been attributed to assassination by ninjas, but the secretive nature of these scenarios have been difficult to prove. Assassins were often identified as ninjas later on, but there is no evidence to prove whether some were specially trained for the task or simply a hired mercenary.

The warlord Oda Nobunaga's notorious reputation led to several attempts on his life. In 1571, a Kōga ninja and sharpshooter by the name of Sugitani Zenjubō was hired to assassinate Nobunaga. Using two arquebuses, he fired two consecutive shots at Nobunaga, but was unable to inflict mortal injury through Nobunaga's armor. Sugitani managed to escape, but was caught four years later and put to death by torture. In 1573, Manabe Rokurō, a vassal of daimyo Hatano Hideharu, attempted to infiltrate Azuchi Castle and assassinate a sleeping Nobunaga. However, this also ended in failure, and Manabe was forced to commit suicide, after which his body was openly displayed in public. According to a document, the Iranki, when Nobunaga was inspecting Iga province — which his army had devastated — a group of three ninjas shot at him with large-caliber firearms. The shots flew wide of Nobunaga, however, and instead killed seven of his surrounding companions.

The ninja Hachisuka Tenzō was sent by Nobunaga to assassinate the powerful daimyo Takeda Shingen, but ultimately failed in his attempts. Hiding in the shadow of a tree, he avoided being seen under the moonlight, and later concealed himself in a hole he had prepared beforehand, thus escaping capture.

An assassination attempt on Toyotomi Hideyoshi was also thwarted. A ninja named Kirigakure Saizō (possibly Kirigakure Shikaemon) thrust a spear through the floorboards to kill Hideyoshi, but was unsuccessful. He was "smoked out" of his hiding place by another ninja working for Hideyoshi, who apparently used a sort of primitive "flamethrower". Unfortunately, the veracity of this account has been clouded by later fictional publications depicting Saizō as one of the legendary Sanada Ten Braves.

Uesugi Kenshin, the famous daimyo of Echigo province was rumored to have been killed by a ninja. The legend credits his death to an assassin, who is said to have hid in Kenshin's lavatory, and gravely injured Kenshin by thrusting a blade or spear into his anus. While historical records showed that Kenshin suffered abdominal problems, modern historians have usually attributed his death to stomach cancer, esophageal cancer or cerebrovascular disease.

Countermeasures

A variety of countermeasures were taken to prevent the activities of the ninja. Precautions were often taken against assassinations, such as weapons concealed in the lavatory, or under a removable floorboard. Buildings were constructed with traps and trip wires attached to alarm bells.

Japanese castles were designed to be difficult to navigate, with winding routes leading to the inner compound. Blind spots and holes in walls provided constant surveillance of these labyrinthine paths, as exemplified in Himeji Castle. Nijō Castle in Kyoto is constructed with long "nightingale" floors, which rested on metal hinges (uguisu-bari) specifically designed to squeak loudly when walked over. Grounds covered with gravel also provided early notice of unwanted intruders, and segregated buildings allowed fires to be better contained.

Training

See also: NinjutsuThe skills required of the ninja has come to be known in modern times as ninjutsu, but it is unlikely they were previously named under a single discipline. Modern misconceptions have identified ninjutsu as a form of combat art, but historically, ninjutsu largely covered espionage and survival skills. Some lineage styles (ryūha) of ninjutsu such as Togakure-ryū were known in the past.

The first specialized training began in the mid-15th century, when certain samurai families started to focus on covert warfare, including espionage and assassination. Like the samurai, ninja were born into the profession, where traditions were kept in, and passed down through the family. According to Turnbull, the ninja was trained from childhood, as was also common in samurai families. Outside the expected martial art disciplines, a youth studied survival and scouting techniques, as well as information regarding poisons and explosives. Physical training was also important, which involved long distance runs, climbing, stealth methods of walking and swimming. A certain degree of knowledge regarding common professions was also required if one was expected to take their form in disguise. Some evidence of medical training can be derived from one account, where an Iga ninja provided first-aid to Ii Naomasa, who was injured by gunfire in the Battle of Sekigahara. Here the ninja reportedly gave Naomasa a "black medicine" meant to stop bleeding.

With the fall of the Iga and Kōga clans, daimyos could no longer recruit professional ninjas, and were forced to train their own shinobi. The shinobi was considered a real profession, as demonstrated in the bakufu's 1649 law on military service, which declared that only daimyos with an income of over 10,000 koku were allowed to retain shinobi. In the two centuries that followed, a number of ninjutsu manuals were written by descendants of Hattori Hanzō as well as members of the Fujibayashi clan, an offshoot of the Hattori. Major examples include the Ninpiden (1655), the Bansenshukai (1675), and the Shōninki (1681).

Some practitioners of modern ninjutsu include Stephen K. Hayes and Masaaki Hatsumi, who is the head (sōke) of Bujinkan, a martial arts organization based in Japan. However, the link between modern interpretations of ninjutsu and historical practices is a matter of debate.

Tactics

The ninja did not always work alone. Teamwork techniques exist, for example, in order to scale a wall, a group of ninja may carry each other on their backs, or provide a human platform to assist an individual in reaching greater heights.. The Mikawa Go Fudoki gives an account where a coordinated team of attackers used passwords to communicate. The account also gives a case of deception, where the attackers dressed in the same clothes as the defenders, causing much confusion. When a retreat was needed during the Siege of Osaka, ninja were commanded to fire upon friendly troops from behind, causing the troops to charge backwards in order to attack a perceived enemy. This tactic was used again later on as a method of crowd dispersal.

Most ninjutsu techniques recorded in scrolls and manuals revolve around ways to avoid detection, and methods of escape. These techniques were loosely grouped under corresponding natural elements. Some examples are:

- Hitsuke - The practice of distracting guards by starting a fire away from the ninja's planned point of entry. Falls under "fire techniques" (katon-no-jutsu).

- Tanuki-gakure - The practice of climbing a tree and camouflaging oneself within the foliage. Falls under "wood techniques" (mokuton-no-jutsu).

- Ukigusa-gakure - The practice of throwing duckweed over water in order to conceal underwater movement. Falls under "water techniques" (suiton-no-jutsu).

- Uzura-gakure - The practice of curling into a ball and remaining motionless in order to appear like a stone. Falls under "earth techniques" (doton-no-jutsu).

Disguises

The use of disguises is common and well documented. Disguises came in the form of priests, entertainers, fortune tellers, merchants, rōnin, and monks. The Buke Myōmokushō states,

Shinobi-monomi were people used in secret ways, and their duties were to go into the mountains and disguise themselves as firewood gatherers to discover and acquire the news about an enemy's territory ... they were particularly expert at travelling in disguise.

A mountain ascetic (yamabushi) attire facilitated travel, as they were common and could travel freely between political boundaries. The loose robes of Buddhist priests also allowed concealed weapons, such as the tantō. Minstrel or sarugaku outfits could have allowed the ninja to spy in enemy buildings without rousing suspicion. Disguises as a komusō, a mendicant monk known for playing the shakuhachi, were also effective, as the large "basket" hats traditionally worn by them concealed the head completely.

Equipment

Ninjas utilized a large variety of tools and weaponry, some of which were commonly known, but others were more specialized. Most were tools used in the infiltration of castles. A wide range of specialized equipment is described and illustrated in the 17th century Bansenshukai, including climbing equipment, extending spears, rocket-propelled arrows, and small collapsible boats.

Outerwear

While the image of a ninja clad in black garbs (shinobi shōzoku) is prevalent in popular media, there is no written evidence for such a costume. Instead, it was much more common for the ninja to be disguised as civilians. The popular notion of black clothing is likely rooted in artistic convention. Early drawings of ninjas were shown to be dressed in black in order to portray a sense of invisibility. This convention was an idea borrowed from the puppet handlers of bunraku theater, who dressed in total black in an effort to simulate props moving independently of their controls. Despite the lack of hard evidence, it has been put forward by some authorities that black robes, perhaps slightly tainted with red to hide bloodstains, was indeed the sensible garment of choice for infiltration.

Clothing used was similar to that of the samurai, but loose garments (such as leggings) were tucked into trousers or secured with belts. The tenugui, a piece of cloth also used in martial arts, had many functions. It could be used to cover the face, form a belt, or assist in climbing.

The historicity of armor specifically made for ninjas cannot be ascertained. While pieces of light armor purportedly worn by ninjas exist and date to the right time, there is no hard evidence of their use in ninja operations. Depictions of famous persons later deemed ninjas often show them in samurai armor. Existing examples of purported ninja armor feature lamellar or ring mail, and were designed to be worn under the regular garb. Shin and arm guards, along with metal-reinforced hoods are also speculated to make up the ninja's armor.

Tools

Tools used for infiltration and espionage are some of the most abundant artifacts related to the ninja. Ropes and grappling hooks were common, and were tied to the belt. A collapsible ladder is illustrated in the Bansenshukai, featuring spikes at both ends to anchor the ladder. Spiked or hooked climbing gear worn on the hands and feet also doubled as weapons. Other implements include chisels, hammers, drills, picks and so forth.

The kunai was a heavy pointed tool, possibly derived from the Japanese masonry trowel, to which it closely resembles. Although it is often portrayed in popular culture as a weapon, the kunai was primarily used for gouging holes in walls. Knives and small saws (hamagari) were also used to create holes in buildings, where they served as a foothold or a passage of entry. A portable listening device (saoto hikigane) was used to eavesdrop on conversations and detect sounds.

The mizugumo was a set of wooden shoes supposedly allowing the ninja to walk on water. They were meant to work by distributing the wearer's weight over the shoes' wide bottom surface. The word mizugumo is derived from the native name for the Japanese water spider (Argyroneta aquatica japonica). The mizugumo was featured on the show Mythbusters, where it was demonstrated unfit for walking on water. The ukidari, a similar footwear for walking on water, also existed in the form of a round bucket, but was probably quite unstable. Inflatable skins and breathing tubes allowed the ninja stay underwater for longer periods of time.

Despite the large array of tools available to the ninja, the Bansenshukai warns one not to be overburdened with equipment, stating "...a successful ninja is one who uses but one tool for multiple tasks".

Weaponry

Although shorter swords and daggers were used, the katana was probably the ninja's weapon of choice, and was sometimes carried on the back. The katana had several uses beyond normal combat. In dark places, the scabbard could be extended out of the sword, and used as a long probing device. The sword could also be laid against the wall, where the ninja could use the sword guard (tsuba) to gain an higher foothold. While straightswords were used before the invention of the katana, the straight ninjatō has no historical precedent and is likely a modern invention.

An array of darts, spikes, knives, and sharp, star-shaped discs were known collectively as shuriken. While not exclusive to the ninja, they were an important part of the arsenal, where they could be thrown in any direction. Bow were used for sharpshooting, and some ninjas bows were intentionally made smaller than the traditional yumi (longbow). The chain and sickle (kusarigama) was also used by the ninja. This weapon consisted of a weight on one end of a chain, and a sickle (kama) on the other. The weight was swung to injure or disable an opponent, and the sickle used to kill at close range.

Introduced explosives from China was known in Japan by the time of the Mongol Invasions (13th century). Later, explosives such as hand-held bombs and grenades were adopted by the ninja. Soft-cased bombs were designed to release smoke or poison gas, along with fragmentation explosives packed with iron or pottery shrapnel.

Along with common weapons, a large assortment of miscellaneous arms were associated with the ninja. Some examples include poison, caltrops, cane swords (shikomizue), land mines, blowguns, poisoned darts, acid-spurting tubes, and firearms. The happō, a small eggshell filled with blinding powder (metsubushi), was also used to faciliate escape.

Legendary abilities

Fuck You Bitch Is one Of The Ninjas Abilities

Famous people

Many famous people in Japanese history have been associated or identified as ninjas, but their status as ninja are difficult to prove and may be the product of later imagination. Rumors surrounding famous warriors, such as Kusunoki Masashige or Minamoto no Yoshitsune sometimes describe them as ninjas, but there is little evidence for these claims. Some well known examples include:

- Mochizuki Chiyome (16th cent.) - The wife of Mochizuke Moritoki. Chiyome created a school for girls, which taught skills required of geisha, as well as espionage skills.

- Fujibayashi Nagato (16th cent.) - Considered to be one of three "greatest" Iga jōnin, the other two being Hattori Hanzō and Momochi Sandayū. Fujibayashi's descendents wrote and edited the Bansenshukai.

- Fūma Kotarō (d. 1603) - A ninja rumored to have killed Hattori Hanzō, with whom he was supposedly rivals. The fictional weapon Fūma shuriken is named after him.

- Hattori Hanzō (1542-1596) - A samurai serving under Tokugawa Ieyasu. His ancestry in Iga province, along with ninjutsu manuals published by his descendants have led some sources to define him as a ninja. This depiction is also common in popular culture.

- Ishikawa Goemon (1558-1594) - Goemon reputedly tried to drip poison from a thread into Oda Nobunaga's mouth through a hiding spot in the ceiling, but many fanciful tales exist about Goemon, and this story cannot be confirmed.

- Kumawakamaru (13th-14th cent.) - A youth whose exiled father was ordered to death by the monk Homma Saburō. Kumakawa took his revenge by sneaking into Homma's room while he was asleep, and assassinating Homma with his own sword.

- Momochi Sandayū (16th cent.) - A leader of the Iga ninja clans, who supposedly perished during Oda Nobunaga's attack on Iga province. There is some belief that he escaped death and lived as a farmer in Kii Province. Momochi is also a branch of the Hattori clan.

- Yagyū Muneyoshi (1529-1606) - A renown swordsman of the Shinkage-ryū school. Muneyoshi's grandson, Jubei Muneyoshi, told tales of his grandfather's status as a ninja.

In popular culture

Fuck You Bitch IS A Very Famous Culture!

Self-styled modern groups

- The Angolan special police forces are a paramilitary police force officially referred to as the Emergency Police, but popularly known as “Ninjas”.

- Rebels in the Pool Region of the Republic of the Congo also called themselves "Ninja".

- Red Berets, a Serb paramilitary group of Dragan Vasiljković based in Knin, Croatia, called themselves "Kninjas".

- Some death squad-type armed groups active under Indonesian rule in East Timor called themselves "Ninja". The name seems to have been borrowed from the movies rather than being directly influenced by the Japanese model. The "ninja" gangs were also active elsewhere in Indonesia.

See also

|

|

==Footnotes

Sex !!

References

- Adams, Andrew (1970), Ninja: The Invisible Assassins, Black Belt Communications, ISBN 978-0897500302

- Buckley, Sandra (2002), Encyclopedia of contemporary Japanese culture, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 978-0415143448

- Bunch, Bryan H.; Hellemans, Alexander (2004), The history of science and technology: a browser's guide to the great discoveries, inventions, and the people who made them, from the dawn of time to today, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, ISBN 978-0618221233

- Chamberlain, Basil Hall (2005), The Kojiki: records of ancient matters, Tuttle Publishing, ISBN 978-0804836753

- Crowdy, Terry (2006), The enemy within: a history of espionage, Osprey Publishing, ISBN 978-1841769332

- Draeger, Donn F.; Smith, Robert W. (1981), Comprehensive Asian fighting arts, Kodansha, ISBN 978-0870114366

- Fiévé, Nicolas; Waley, Paul (2003), Japanese capitals in historical perspective: place, power and memory in Kyoto, Edo and Tokyo, Routledge, ISBN 978-0700714094

- Friday, Karl F. (2007), The first samurai: the life and legend of the warrior rebel, Taira Masakado, Wiley, ISBN 978-0471760825

- Howell, Anthony (1999), The analysis of performance art: a guide to its theory and practice, Routledge, ISBN 978-9057550850

- Green, Thomas A. (2001), Martial arts of the world: an encyclopedia, Volume 2: Ninjutsu, ABC-CLIO, ISBN 978-1576071502

- Kawaguchi, Sunao (2008), Super Ninja Retsuden, PHP Research Institute, ISBN 978-4569670737

- McCullough, Helen Craig (2004), The Taiheiki: A Chronicle of Medieval Japan, Tuttle Publishing, ISBN 978-0804835381

- Mol, Serge (2003), Classical weaponry of Japan: special weapons and tactics of the martial arts, Kodansha, ISBN 978-4770029416

- Morton, William Scott; Olenik, J. Kenneth (2004), Japan: it's history and culture, fourth edition, McGraw-Hill Professional, ISBN 978-0071412803

- Nihon Hakugaku Kurabu (2006), Unsolved Mysteries of Japanese History, PHP Research Institute, ISBN 978-4569656526

- Nihon Hakugaku Kurabu (2004), Zuketsu Rekishi no Igai na Ketsumatsu, PHP Research Institute, ISBN 978-4569640617

- Perkins, Dorothy (1991), Encyclopedia of Japan: Japanese History and Culture, from Abacus to Zori, Facts on File, ISBN 978-0816019342

- Ratti, Oscar; Westbrook, Adele (1991), Secrets of the samurai: a survey of the martial arts of feudal Japan, Tuttle Publishing, ISBN 978-0804816847

- Reed, Edward James (1880), Japan: its history, traditions, and religions: With the narrative of a visit in 1879, Volume 2, John Murray, OCLC 1309476

- Satake, Akihiro (2003), Shin Nihon Koten Bungaku Taikei: Man'yōshū Volume 4, Iwanami Shoten, ISBN 4-00-240004-2

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Takagi, Ichinosuke (1962), Nihon Koten Bungaku Taikei: Man'yōshū Volume 4, Iwanami Shoten, ISBN 4-00-060007-9

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Tatsuya, Tsuji (1991), The Cambridge history of Japan Volume 4: Early Modern Japan: Chapter 9, translated by Harold Bolitho, edited by John Whitney Hall, New York: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0521223553

- Teeuwen, Mark; Rambelli, Fabio (2002), Buddhas and kami in Japan: honji suijaku as a combinatory paradigm, RoutledgeCurzon, ISBN 978-0415297479

- Turnbull, Stephen (2003), Ninja AD 1460-1650, Osprey Publishing, ISBN 978-1841765259

- Turnbull, Stephen (2007), Warriors of Medieval Japan, Osprey Publishing, ISBN 978-1846032202

- Waterhouse, David (1996), Religion in Japan: arrows to heaven and earth, article 1: Notes on the kuji, edited by Peter F. Kornicki and James McMullen, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0521550284

Further reading

Read About Sex!

External links

- How Ninja Work at How Stuff Works

- Iga-ryu Ninja Museum

- History of the concept of the ninja, especially in theatre

- Ratti & Westbrook 1991, p. 325

- Turnbull 2003, pp. 5–6

- ^ Turnbull 2003, p. 17; Turnbull uses the name Buke Meimokushō, an alternate reading for the same title. The Buke Myōmokushō cited here is a much more common reading.

- Crowdy 2006, p. 50

- ^ Green 2001, p. 355

- ^ Green 2001, p. 358; based on different readings, Ninpiden is also known as Shinobi Hiden, and Bansenshukai can also be Mansenshukai.

- Takagi et al. 1962, p. 191 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFTakagi_et_al.1962 (help); the full poem is "Yorozu yo ni / Kokoro ha tokete / Waga seko ga / Tsumishi te mitsutsu / Shinobi kanetsumo".

- Satake et al. 2003, p. 108 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFSatake_et_al.2003 (help); the Man'yōgana used for "shinobi" is 志乃備, its meaning and characters are unrelated to the later mercenary shinobi.

- Perkins 1991, p. 241

- Turnbull 2003, p. 6

- Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed.; American Heritage Dictionary, 4th ed.; Dictionary.com Unabridged (v 1.1).

- ^ Turnbull 2003, p. 29

- Turnbull 2003, p. 42

- Turnbull 2007, p. 149

- ^ Turnbull 2003, p. 27

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

ratti 1991 327was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - Turnbull 2003, p. 28

- Turnbull 2003, p. 43

- ^ Turnbull 2003, pp. 43–44

- Cite error: The named reference

Turnbull 2003 5was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Turnbull 2003, p. 31

- Turnbull 2003, pp. 31–32

- Turnbull 2003, p. 30

- Turnbull 2003, p. 32

- Nihon Hakugaku Kurabu 2006, p. 36

- Nihon Hakugaku Kurabu 2004, pp. 51–53; Turnbull 2003, p. 32

- Turnbull 2003, p. 26

- Draeger & Smith 1981, pp. 128–129

- Turnbull 2003, pp. 29–30

- Fiévé & Waley 2003, p. 116

- Turnbull 2003, p. 12

- ^ Turnbull 2003, pp. 14–15

- Green 2001, pp. 359–360

- Deal 2007, p. 156 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFDeal2007 (help)

- ^ Turnbull 2003, p. 48

- Turnbull 2003, p. 13

- ^ Turnbull 2003, p. 22

- Cite error: The named reference

Turnbull 2003 44 46was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - Cite error: The named reference

Turnbull 2003 50was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Draeger & Smith 1981, p. 125

- Crowdy 2006, p. 51

- Deal 2007, p. 161 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFDeal2007 (help)

- ^ Turnbull 2003, p. 18

- ^ Turnbull 2003, p. 19

- Turnbull 2003, p. 60

- ^ Draeger & Smith 1981, p. 128

- Turnbull 2003, p. 16

- Howell 1999, p. 211

- Turnbull 2003, p. 20

- Mol 2003, p. 121

- Turnbull 2003, p. 61

- Turnbull 2003, pp. 20–21

- Turnbull 2003, p. 21

- Turnbull 2003, p. 62

- ^ Ratti & Westbrook 1991, p. 329

- Green 2001, p. 359

- Adams 1970, p. 52

- Adams 1970, p. 49

- Reed 1880, pp. 269–270

- Mol 2003, p. 119

- Ratti & Westbrook 1991, pp. 328–329

- Ratti & Westbrook 1991, p. 328

- Adams 1970, p. 55

- Bunch & Hellemans 2004, p. 161

- Mol 2003, p. 176

- Mol 2003, p. 195

- Draeger & Smith 1981, p. 127

- Mol 2003, p. 124

- McCullough 2004, p. 49

- Green 2001, p. 671

- Adams 1970, p. 34

- Adams 1970, p. 160

- McCullough 2004, p. 48

- Adams 1970, p. 42

- Reuters AlertNet (October 10, 2007), Elite "Ninja" police free hostages in Sao Tome, Reuters, retrieved August 26, 2009

{{citation}}:|last=has generic name (help) - Tsoumou, Christian (June 8, 2007), Congo's Ninja rebels burn weapons and pledge peace, Reuters, retrieved August 26, 2009

- Robinson, Natasha; Madden, James (April 13, 2007), Captain Dragan set for extradition, The Australian, retrieved August 26, 2009

- Lane, Max (March 1, 1995), 'Ninja' terror in East Timor, Green Left Online, retrieved August 26, 2009

- BBC News (October 24, 1998), Indonesia's 'ninja' war, BBC, retrieved August 26, 2009