This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Rfts (talk | contribs) at 01:16, 6 October 2009 (typo). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 01:16, 6 October 2009 by Rfts (talk | contribs) (typo)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Spanish. (March 2009) Click for important translation instructions.

|

Juan Manuel de Rosas (born Juan Manuel José Domingo Ortiz de Rozas y López de Osornio in Buenos Aires, March 30, 1793 – Southampton, Hampshire, March 14, 1877), was a conservative Argentine politician who governed the Buenos Aires Province from 1829 to 1832 and again, from 1835 to 1852. Rosas was one of the first famous caudillos in Ibero-America and through his rule united Argentina, provided an efficient government and strengthened the economy. The change in family name from Rozas to Rosas came because his mother told him he was stealing her cattle. Furious he changed his family name. He begun after that as an "arriero", carrying cattle through the immensities of the pampas.

He was the son of León Ortiz de Rosas y de la Cuadra and wife Agustina Teresa López de Osornio. Born to one of the wealthiest families in the River Plate region, Rosas ran away from home at a young age and began working in the fields while relatives offered him food and shelter. He married right before age 20 on March 16, 1813 to the almost 18-year-old María de la Encarnación de Ezcurra y Arguibel and they had one child, a daughter Manuela Robustiana de Rosas y Ezcurra, born in Buenos Aires on May 24, 1817. Rosas established a meat-salting plant when he was twenty-two and the business immediately flourished. It became so successful that ranchers were afraid Rosas' business would become more popular than their own and laws were passed to end his plant.

Rosas bought a large amount of land and began living the typical rancher's life. Instead of fighting with the gauchos, he became one of them and earned their respect and trust. When civil war broke out in 1820, Rosas organized a regiment of gauchos and soon became a national figure through his efforts to restore peace and order.

After Lavalle's army murdered Manuel Dorrego, who was head of government in Buenos Aires, the position was open and in 1829 Rosas was elected as governor of Buenos Aires. He had a successful and popular first term but refused to run for a second term even though public support was strong. In subsequent years, Rosas went in and out of power, but remained a strong leader.

During his years out of office (1832-1835), Rosas waged a military campaign against the indigenous population in southern Argentina. As Charles Darwin related in The Voyage of the Beagle, he met Rosas in the early 1830s, who was then engaged in exterminating tribes of wandering horse-mounted Indians, describing him as a man of extraordinary character, a perfect horseman who conformed to the dress and habits of the Gauchos and "obtained an unbounded popularity in the countryside, and in consequence a despotic power". Darwin included a story of how Rosas had himself put in the stocks for inadvertently breaking his own rule of not wearing knives on Sundays. This appealed to his men's sense of egalitarianism and justice. In his Palermo house, which in fact was Argentina's government house, in the evenings balls, he used buffoons to tell foreign Ambassadors harsh things which had to be taken as coming from buffoons; in fact he was sending them.

In 1835, Rosas was offered "la suma del poder" which gave him total power with no oversight and his dictatorial regime began.

To enforce the dictator's will there arose a secret organization known as the Mazorcas, a militia that beat up or even murdered Rosas' opponents.

As a leader, Rosas portrayed himself as a man of the people, who could relate to the working class of gauchos and Afro-Argentines. Rosas used his man of the people ideal to unify Argentina during his era. Rosas also invited the Jesuits back into the country and because of this move they supported him whole-heartedly. Rosas supporters called themselves Rosistas. Rosas also had his portrait be displayed in all churches and public places as a symbol of complete control. Rosas claimed to be a Federalist but really was a centralist and established unity through tyranny. Rosas' rule was filled with violence — he killed his opponents and anyone else who would not support him.

His wife Encarnación died in Buenos Aires on October 20, 1838.

The people who opposed Rosas formed a group called Asociacion de Mayo-May Brotherhood. It was a literary group that became politically active and aimed at exposing Rosas' actions. Some of the literature against him includes The Slaughter House, Socialist Dogma, Amalia and Facundo. Meetings which had high attendance at first soon had few members attending out of fear of prosecution. Rosas' opponents during his rule were dissidents, such as José María Paz, Salvador M. del Carril, Juan Bautista Alberdi, Esteban Echeverria, Bartolomé Mitre and Domingo Faustino Sarmiento. Rosas political opponents were exiled to other countries, such as Uruguay and Chile.

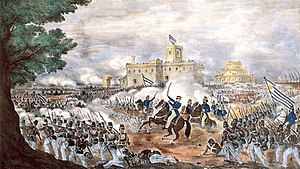

By the end of his reign, many of his supporters turned on him. General Urquiza, who was governor of the Entre Ríos Province and once backed Rosas, organized an army against him. Other provinces as well as Brazil and Uruguay joined the fight to take down the dictator. On February 3, 1852, Rosas was overthrown when his army was defeated at the Battle of Caseros. After Caseros battle Rosas spent the rest of his life in exile, in the United Kingdom, as a farmer in Southampton. He was initially buried in the Southampton Old Cemetery in Southampton Common until his body was exhumed in 1989 and transferred to the La Recoleta Cemetery in Argentina.

Rosas received the 'combat sable' from General San Martin, 'maximum hero' of Argentina, who judged that Rosas was the only man capable of defending Argentina against the European powers, especially the British.

In the aftermath of the Battle of Caseros, Martin de Santa Coloma (or Colonel Martiniano Chilavert), who passionately resisted the Unitarians, was pursued and assassinated in Belgrano, a district of Buenos Aires. This was the Unitarians' idea of justice. Sarmiento, future Ambassador to USA and Argentinian President, hated him enough to offer as a Sunday spectacle the dynamite blowing of his house, which had been durng 25 years Argentina's Government House.

See also

References

- Argentine Caudillo: Juan Manuel de Rosas, by John Lynch (1981, 2001).

- Crow, John A. The Epic of Latin America. New York: University of California P, 1992.

- "Juan Manuel de Rosas." Britannica. 2008. 25 Oct. 2008.

| Preceded byManuel Dorrego | Governor of Buenos Aires Province (Head of State of Argentina) 1829-1832 |

Succeeded byJuan Ramón Balcarce |

| Preceded byManuel Vicente Maza | Governor of Buenos Aires Province (Head of State of Argentina) 1835-1852 |

Succeeded byVicente López y Planes |

| Heads of state of Argentina | ||

|---|---|---|

| May Revolution and Independence War Period up to Asamblea del Año XIII (1810–1814) | ||

| Supreme directors of the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata (1814–1820) | ||

| Unitarian Republic – First Presidential Government (1826–1827) | ||

| Pacto Federal and Argentine Confederation (1827–1862) | ||

| National Organization – Argentine Republic (1862–1880) | ||

| Generation of '80 – Oligarchic Republic (1880–1916) | ||

| First Radical Civic Union terms, after secret ballot (1916–1930) | ||

| Infamous Decade (1930–1943) | ||

| Revolution of '43 – Military Dictatorships (1943–1946) | ||

| First Peronist terms (1946–1955) | ||

| Revolución Libertadora – Military Dictatorships (1955–1958) | ||

| Fragile Civilian Governments – Proscription of Peronism (1958–1966) | ||

| Revolución Argentina – Military Dictatorships (1966–1973) | ||

| Return of Perón (1973–1976) | ||

| National Reorganization Process – Military Dictatorships (1976–1983) | ||

| Return to Democracy (1983–present) | ||