This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Bcorr (talk | contribs) at 22:18, 20 December 2005 (Reverted edits by 84.68.144.237 (talk) to last version by Bcorr). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 22:18, 20 December 2005 by Bcorr (talk | contribs) (Reverted edits by 84.68.144.237 (talk) to last version by Bcorr)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)

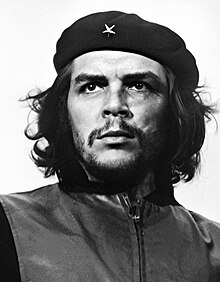

Dr. Ernesto Rafael Guevara de la Serna (June 14, 1928 – October 9, 1967), commonly known as Che Guevara or el Che, was an Argentinian-born Marxist revolutionary and Cuban guerrilla leader. Guevara was a member of Fidel Castro's 26th of July Movement that seized power in Cuba in 1959. After serving in various important posts in the new government and writing a number of articles and books on the theory and practice of guerrilla warfare, Guevara left Cuba in 1965 with the intention of fomenting revolutions first in the Congo-Kinshasa (later named the Democratic Republic of the Congo) and then in Bolivia, where he was captured in a CIA-organized military operation. It is believed by some that the CIA wished to interrogate Guevara but, after his capture in the Yuro ravine, he died at the hands of the Bolivian Army in La Higuera near Vallegrande on October 9 1967. Participants in and witnesses to the events of his final hours testify that his captors summarily executed him, perhaps to avoid a public trial followed by imprisonment in Bolivia. After his death, Guevara became an icon of socialist revolutionary movements worldwide, perhaps in part because of an arresting visual image based on a photograph by Alberto Korda and a generally romanticised image.

Youth

Guevara was born in Rosario, Argentina, the eldest of five children in a family of mixed Spanish, Basque and Irish descent. The date of birth recorded on his birth certificate was June 14, 1928, although some sources assert that he was actually born on May 14 1928 and the birth certificate falsified to shield the family from a potential scandal relating to his mother's having been three months pregnant when she was married.

One of Guevara's forebears, Patrick Lynch, was born in Galway, Ireland in 1715. He left for Bilbao, Spain, and traveled from there to Argentina. Francisco Lynch (Guevara's great-grandfather) was born in 1817, and Ana Lynch (his beloved grandmother) in 1861. Her son Ernesto Guevara Lynch (Guevara's father) was born in 1900. Guevara Lynch married Celia de la Serna y Llosa in 1927 and they had five children.

In this upper class family with leftist leanings, Guevara became known for his dynamic and radical perspective even as a boy. Though suffering from the crippling bouts of asthma that were to afflict him throughout his life, he excelled as an athlete. He was an avid rugby player despite his handicap, and earned the nickname "Fuser" for his aggressive style of play. In 1948, he entered the University of Buenos Aires to study medicine. There, after some interruptions, he completed his medical studies in March 1953.

While a student, Guevara spent a long time traveling around Latin America. In 1951, Guevara's older friend, Alberto Granado, a biochemist and a political radical, suggested that Guevara take a year off from his medical studies to embark on a trip they had talked of doing for years, traversing South America. Guevara and the 29-year-old Alberto soon set off from their hometown of Alta Gracia, riding a 1939 Norton 500 cc motorcycle nicknamed La Poderosa II meaning "the mighty one", with the idea of spending a few weeks volunteering at the San Pablo leper colony in Peru on the banks of the Amazon River during the trip. Guevara narrated this journey in The Motorcycle Diaries, translated in 1996 (and turned into a motion picture of the same name in 2004).

Through his first-hand observations of the poverty, oppression and powerlessness of the masses, Guevara decided that the only remedy for Latin America's economic and social inequities lay in revolution. His travels also inspired him to look upon Latin America not as a collection of separate nations but as a single cultural and economic entity, the liberation of which would require an intercontinental strategy. He began to develop his concept of a united Ibero-America without borders, bound together by a common 'mestizo' culture, an idea that would figure prominently in his later revolutionary activities. Upon his return to Argentina, he completed his medical studies as quickly as he could, in order to continue his travels around South and Central America.

Guatemala

Following his graduation from the University of Buenos Aires medical school in 1953, Guevara went on to Guatemala, where President Jacobo Arbenz Guzmán headed a populist government that, through various reforms, particularly land reform, was attempting, by sometimes bloody means, to bring about a social revolution. Around this time, Guevara also acquired his famous nickname, "Che", due to his frequent use of the Argentine word Che (pronounced /tʃe/), used in a similar way to "pal" or "mate" as used colloquially in various English-speaking countries. The word is used in some other Spanish-speaking countries, with some differences in usage.

The overthrow of the Arbenz government by a 1954 CIA-backed coup d'état cemented Guevara's view of the United States as an imperialist power that would consistently oppose governments attempting to address the socioeconomic inequality endemic to Latin America and other developing countries. This helped strengthen his conviction that socialism was the only true way to remedy such problems. Following the coup, Guevara volunteered to fight, but Arbenz told his foreign supporters to leave the country, and Guevara briefly took refuge in the Argentine consulate before moving on to Mexico.

Cuba

Guerrilla Fighter

(January 1, 1959)

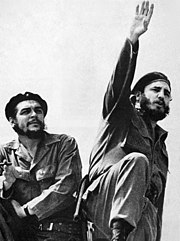

Guevara met Fidel Castro and Fidel's brother Raúl in Mexico City where the two sought refuge after being exiled from Cuba. The Castro brothers were preparing to return to Cuba with an expeditionary force in an attempt to overthrow General Fulgencio Batista, who had assumed dictatorial powers following a coup d'état during the 1952 presidential elections. Guevara quickly joined the "26th of July Movement", named in commemoration of the date of the failed attack on the Moncada barracks that was the cause of Castro's exile.

Castro, Guevara, and approximately 80 other guerrillas departed from Tuxpan, Veracruz, aboard the cabin cruiser Granma (probably named for the grandmother of the previous, American, owner) in November 1956. Guevara was the only non-Cuban aboard.

The landing was planned to coincide with an uprising in Santiago de Cuba on 30 November, but Granma was conveniently delayed, the uprising was put down, and, shortly after disembarking in a swampy area near Niquero in southeastern Cuba on 2 December, the expeditionary unit was attacked by Batista's forces. Only 15 rebels survived as a bedraggled fighting unit. Guevara, the group's physician, laid down his knapsack containing medical supplies in order to pick up a box of ammunition dropped by a fleeing comrade, a moment which he later recalled as marking his transition from physician to combatant.

The remaining rebels fled into the mountains of the Sierra Maestra, where they slowly grew in strength, seizing weapons and winning support and recruits from peasants in rural areas and intellectuals and workers in urban areas. Guevara exhibited great courage, skills in combat, boldness and intrepidity, an outstanding self-discipline, and high expectations towards himself and others, and soon became one of Castro's ablest and most trusted aides. He was also responsible for the execution of many men he accused of being informers, deserters or spies. However, at least some of these were rivals or inconvenient non-ideologues. For instance, even much maligned Eutimio Guerra had been "a land reform organizer."

Within months, Guevara rose to the highest rank, Comandante (literally Commander), in the revolutionary army. His march on Santa Clara in late 1958, which culminated in his column derailing an armored train filled with Batista's troops and taking over the city, was the final blow that forced Batista to flee the country. Guevara recorded the two years spent in overthrowing Batista's regime in a series of articles in Verde Olivo, a weekly publication of the Revolutionary Armed Forces. The articles were published in 1963 as the book Pasajes de la Guerra Revolucionaria, translated into English in 1968 as Reminiscences of the Revolutionary War (retranslated in 1996 as Episodes of the Cuban Revolutionary War).

Member of revolutionary government

After the 26th of July Movement entered the capital of Havana on January 2, 1959, a new socialist government was established. Shortly thereafter, Guevara was declared "a Cuban citizen by birth" and divorced his Peruvian wife, Hilda Gadea, with whom he had one daughter. Later he married a member of Castro's army, Aleida March. The couple would have four children together.

Che Guevara became as prominent in the new government as he had been in the revolutionary army. In 1959, he was appointed commander of the La Cabaña Fortress prison. During his six months tenure in this post (January 2 through June 12 1959), he oversaw the trial and execution of many people including former Batista regime officials, members of the BRAC secret police, alleged war criminals, and political dissidents. Different sources cite different numbers of executions. Some sources say 156 people were executed, while others give far higher figures.

Later, Guevara became an official at the National Institute of Agrarian Reform, President of the National Bank of Cuba, and Minister of Industries. In this capacity, Guevara faced the challenge of transforming Cuba's capitalist agrarian economy into a socialist industrial economy. After negotiating a trade agreement with the Soviet Union in 1960, Guevara represented Cuba on many missions and delegations to Soviet-aligned nations in Africa and Asia after the U.S. imposed an embargo on the nation.

Guevara helped guide Cuba on its socialist path. An active participant in the economic and social reforms implemented by the government, he became known in the West for his fiery attacks on U.S. foreign policy in Africa, Asia, and especially Latin America.

(Havana - April 1961)

During this period, he defined Cuba's policies and his own views in many speeches, articles, letters, and essays. His highly influential manual on guerrilla strategy and tactics (English translation, Guerrilla Warfare, (1961)) advocated peasant-based revolutionary movements in the developing countries. However, this manual lacked practical application as demonstrated by Guevara's repeated lack of success. El socialismo y el hombre en Cuba (1965), published in English as Man and Socialism in Cubain 1967, is an examination of Cuba's new brand of Socialism and Communist ideology. The ideal Communist society is not possible unless the people first evolve into a 'new man' (el Hombre Nuevo). For this a socialist state would first be necessary, a ladder to be ascended and then cast away in a society of equals without states or governments.

Prior to the Cuban Missile Crisis, Guevara was part of a Cuban delegation to Moscow in early 1962 with Raúl Castro where he endorsed the planned placement of Soviet nuclear missiles in Cuba. Guevara believed that the installation of Soviet missiles would protect Cuba from any direct military action against it by the United States. Jon Lee Anderson reports that after the crisis Guevara told Sam Russell, a British correspondent for the socialist newspaper Daily Worker, that if the missiles had been under Cuban control, they would have fired them.

The ideas presented in Guevara's book, Guerrilla Warfare, demonstrate his philosophy for fighting irregular wars. Guevara believed that a small group (foco) of guerrillas, by violently targeting the government, could actively foment revolutionary sentiment among the general populace, so that it was not necessary to build broad organizations and advance the revolutionary struggle in measured steps before launching an armed insurrection. However, the failure of his "Cuban Style" revolution in Bolivia was thought to have been due to his lack of grassroots support there, and hence this strategy is now thought by some to be ineffective. It worked in Cuba because the people already wanted to get rid of Batista. All they needed was a vanguard to inspire them.

As a government official, Guevara served as an example of the "New Man" (el Hombre Nuevo). He regularly devoted his weekends and evenings to volunteer labour, be it working at shipyards, in textile factories or cutting sugarcane. He believed such sacrifice and dedication on the part of the people was necessary to achieve Communism through the Socialist society. Guevara was also known for his austerity, simple lifestyle and habits. For example, upon becoming a member of the government, he refused an increase in pay, opting to continue drawing the (considerably) lower salary he received as a Comandante (Major), in the Rebel Army. This austerity also manifested itself as a general dislike of luxury. Once, on a trip to Russia, Guevara was dining with high-ranking officials from the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, when the group's food was served to them on expensive china. To the Russians, Guevara caustically remarked, "Is this how the proletariat lives in Russia?"

Possible role in the continuing revolution

On November 18, 2005, authors Lamar Waldron and Thom Hartmann published Ultimate Sacrifice, a new book on a previously undocumented plan for a Cuban coup led by an influential revolutionary and key government figure in Cuba that after killing Castro, would invite the military support of the United States to remove Castro supporting military forces including Soviet forces from Cuba. Ultimately, the coup leader was planned to announce free democratic elections in Cuba.

While the authors explicitly state that they believe that to specifically identify any individual referenced in the book as the coup leader would be a potential violation of U.S. laws protecting intelligence agents and sources, they regularly present references to the coup leader with historical text and documents relating Che Guevara's then current position and thoughts.

According to their text, Che Guevara was becoming disillusioned with the increasing Soviet presence in Cuba and with the totalitarian stylings of Castro. Additionally, he had been losing authority and influence within the government following the U.S. supported Bay of Pigs invasion. During the Revolution, Che had been in contact with Enrique Ruiz Williams, a confidant of Robert Kennedy and key figure representing the interests of Cuban exiles following the Bay of Pigs event, where he was captured and later released with about sixty others to pressure the United States to bargain with Castro for the freedom of the remaining thousand-plus militants.

The imminent coup and subsequent planned U.S. invasion of Cuba were scuttled by the assassination of JFK on November 22, 1963, when Lyndon Johnson refused to continue the nascent plans that he had had no part in designing.

Disappearance from Cuba

(New York City - December 11, 1964)

In December 1964, Che Guevara went to New York City to visit the UN. While there, he had little-known meetings with three associates of Robert Kennedy: newsman Tad Szulc, Senator Eugene McCarthy, and journalist Lisa Howard. A few weeks later, in January 1965, a Cuban exile supported by Robert Kennedy in 1963, Eloy Menoyo, was arrested while on a secret mission into Cuba. After April 1965 Guevara dropped out of public life and then vanished altogether. He was not seen in public after his return to Havana on March 14 from a three-month tour during which he visited the People's Republic of China, the United Arab Republic (Egypt), Algeria, Ghana, Guinea, Mali, Dahomey, Congo-Brazzaville and Tanzania. Guevara's whereabouts were the great mystery of 1965 in Cuba, as he was regarded as second in power to Castro himself. His disappearance was variously attributed to the relative failure of the industrialization scheme he had advocated while minister of industry, to pressure exerted on Castro by Soviet officials disapproving of Guevara's pro-Chinese Communist tendencies as the Sino-Soviet split grew more pronounced, and to serious differences between Guevara and the Cuban leadership regarding Cuba's economic development and ideological line. It may also be that Fidel had grown increasingly wary of Che Guevara's popularity and considered him a potential threat. Castro's explanations for Che's disappearance have always been suspect (see below) and many found it surprising that Che never announced his intentions publicly, but only through an undated letter to Castro.

Guevara's pro-Chinese orientation was increasingly problematic for Cuba as the nation's economy became more and more dependent on the Soviet Union. Since the early days of the Cuban revolution Guevara had been considered an advocate of Maoist strategy in Latin America and the originator of a plan for the rapid industrialization of Cuba which some compared to China's "Great Leap Forward". According to Western "observers" of the Cuban situation, the fact that Guevara was opposed to Soviet conditions and recommendations that Castro seemed obliged to accept might have been the reason for his disappearance. However, both Guevara and Castro were supportive of the idea of a united front, including the Soviet Union and China, and had made several unsuccessful attempts to reconcile the feuding parties.

Indeed, by this point Guevara had grown more skeptical of the Soviet Union. He saw the Northern Hemisphere, led by the US in the West and the Soviets in the East, as the exploiter of the Southern Hemisphere. But he strongly supported pro-Soviet Communist North Vietnam in the Vietnam War, and urged South Americans to take up arms and create "many Vietnams".

Pressed by international speculation regarding Guevara's fate, Castro stated on June 16, 1965 that the people would be informed about Guevara when Guevara himself wished to let them know. Numerous rumors about his disappearance spread both inside and outside Cuba. On October 3 of that year, Castro revealed an undated letter purportedly written to him by Guevara some months earlier in which Guevara reaffirmed his enduring solidarity with the Cuban Revolution but stated his intention to leave Cuba to fight abroad for the cause of the revolution. He explained that "other nations of the world are calling for the help of my modest efforts" and that he had therefore decided to go and fight as a guerrilla "on new battlefields". In the letter Guevara announced his resignation from all his positions in the government, in the party, and in the Army, and renounced his Cuban citizenship, which had been granted to him in 1959 in recognition of his efforts on behalf of the revolution.

During an interview with four foreign correspondents on November 1, Castro remarked that he knew where Guevara was but would not disclose his location, and added, denying reports that his former comrade-in-arms was dead, that "he is in the best of health." Despite Castro's assurances, the fate of Guevara remained a mystery at the end of 1965. Guevara's movements and whereabouts continued to be a closely held secret for the next two years.

Congo

During their all-night meeting on March 14 - March 15 1965, Guevara and Castro had agreed that he would personally lead Cuba's first military action in Africa. Some usually reliable sources state that Guevara persuaded Castro to back him in this effort, while other sources of equal reliability maintain that Castro convinced Che to undertake the mission, as the conditions in many places of Latin America were not optimal. Fidel himself has said the latter is true. The Cuban operation was to be carried out in support of the pro-Lumumba, Marxist Simba movement in the former Belgian Congo (later Zaïre and currently the Democratic Republic of the Congo).

In 1965, Guevara was assisted for a time in the former Belgian Congo by guerrilla leader Laurent-Désiré Kabila, who helped Lumumba supporters lead a revolt that was suppressed in November of that same year by the Congolese army and a large group of white mercenaries. Guevara dismissed him as insignificant. "Nothing leads me to believe he is the man of the hour," Guevara wrote.

Guevara was 37 at the time and had no formal military training. His asthma prevented him from entering military service in Argentina, a fact of which he was proud, given his opposition to the government. He had the experiences of the Cuban revolution, including his successful march on Santa Clara, which was central to Batista finally being overthrown by Castro's forces.

CIA advisors working with the Congolese army were able to monitor Guevara's communications, arrange to ambush the rebels and the Cubans whenever they attempted to attack, and interdict Guevara's supply lines. Guevara's aim was to export the Cuban Revolution by teaching local Simba fighters in communist ideology and strategies of guerrilla warfare. The incompetence, intransigence, and infighting of the local Congolese forces are cited by Che in his Congo Diaries as the key reasons for the revolt's failure. Later that same year, ill, suffering from his asthma and frustrated after seven months of hardship, Guevara left the Congo with the Cuban survivors (six of Guevara's column had died). At one point, Guevara considered sending the wounded back to Cuba, then standing alone and fighting until the end in Congo as a revolutionary example; but after being persuaded by his comrades in arms, he left the Congo.

Because Fidel Castro had made public Che's "farewell letter" to him in which he wrote that he was severing all ties with Cuba in order to devote himself to revolutionary activities in other parts of the world, Guevara felt that he could not return to Cuba for moral reasons, and he spent the next six months living clandestinely in Dar-es-Salaam, Prague and the GDR. During this time he compiled his memoirs of the Congo experience, and also wrote drafts of two more books, one on philosophy and the other on economics. Throughout this period, Castro said he continued to importune him to return to Cuba, but Guevara only agreed to do so when it was understood that he would be there on a strictly temporary basis for the few months needed to prepare a new revolutionary effort somewhere in Latin America, and that his presence on the island would be cloaked in the tightest secrecy.

Bolivia

Insurgent

Speculation on Guevara's whereabouts continued throughout 1966 and into 1967. Finally, in a speech at the 1967 May Day rally in Havana, the Acting Minister of the armed forces, Maj. Juan Almeida, announced that Guevara was "serving the revolution somewhere in Latin America". The persistent reports that he was leading the guerrillas in Bolivia were ultimately shown to be true.

A parcel of jungle land in the Ñancahuazú region was purchased by native Bolivian Communists and turned over to him for use as a training area. The evidence suggests that this training was more hazardous than combat to Guevara and the Cubans accompanying him. Little was accomplished in the way of building a guerrilla army. On learning of his presence in Bolivia, President René Barrientos is alleged to have expressed the desire to see Guevara's head displayed on a pike in downtown La Paz. He ordered the Bolivian Army to hunt Guevara and his followers down.

Guevara's guerrilla force, numbering about 50 and operating as the Ejército de Liberación Nacional de Bolivia (ELN) was well equipped and scored a number of early successes in difficult terrain in the mountainous Camiri region of the country against Bolivian regulars. In September, however, the Army managed to eliminate two guerrilla groups, reportedly killing one of the leaders.

However, Guevara's plan for fomenting revolution in Bolivia appears to have been based upon a number of misconceptions:

- He had expected to deal only with the country's military government and its poorly-trained and equipped army. However, after the US government learned of his location, CIA and other operatives were sent into Bolivia to aid the anti-insurrection effort. The Bolivian Army was being trained, and probably directly assisted, by US Army Special Forces advisors, including a recently organized elite battalion of Rangers trained in jungle warfare.

- Guevara had expected assistance and cooperation from the local dissidents. He did not receive it; and Bolivia's Communist Party, oriented towards Moscow rather than Havana, did not aid him.

- He had expected to remain in contact with Havana. However, the two shortwave transmitters provided to him by Cuba were faulty, so that the guerillas were unable to communicate with Havana. Some months into the campaign, the tape recorder that the guerrillas used to record and decode radio messages sent to them from Havana was lost while crossing a river.

Capture and Execution

(La Higuera, Bolivia - October 9, 1967)

The Bolivian Special Forces were notified of the location of Guevara's guerrilla encampment by a deserter. On October 8, the encampment was encircled and Guevara was captured while leading a patrol in the vicinity of La Higuera. His surrender was offered after being wounded in the legs and having his rifle destroyed by a bullet. According to soldiers present at the capture, during the skirmish as soldiers approached Guevara he allegedly shouted, "Do not shoot! I am Che Guevara and worth more to you alive than dead". This claim is disputed, as some soldiers say this story was set loose to show Guevara in a more humiliating light; the "quote" is even more curious because his identity was not immediately known upon his capture. At the time of his capture, Guevara was wearing a Rolex watch he had received as a gift from Fidel Castro. Barrientos promptly ordered his execution upon being informed of his capture. Guevara was taken to a dilapidated schoolhouse where he was held overnight. Early the next afternoon he was executed, bound by his hands to a board. The executioner was a sergeant in the Bolivian army, who had drawn a short straw and had to shoot Guevara. Several versions exist about what happened next. Some say the executioner was too nervous, left, and was forced back inside. Others say he was so nervous he refused to look Guevara in the face and shot him in the side and the throat, which was the fatal wound. The most widely agreed upon account is that Guevara received multiple shots to the legs, so as to avoid maiming his face for identification purposes and simulate combat wounds in an attempt to conceal his execution. Biting his arm to avoid crying out, he was eventually spared his pain and shot in the chest, filling his lungs with blood. Che Guevara did have some last words before his death; he allegedly said to his executioner, "I know you are here to kill me. Shoot, coward, you are only going to kill a man". His body was lashed to the landing skids of a helicopter and flown to neighboring Vallegrande where it was laid out on a laundry tub in the local hospital and displayed to the press. Photographs taken at that time gave rise to legends such as those of "San Ernesto de La Higuera" and "El Cristo de Vallegrande". After a military doctor surgically amputated his hands, Bolivian army officers transferred Guevara's cadaver to an undisclosed location and refused to reveal whether his remains had been buried or cremated.

A CIA agent and veteran of the US invasion of Cuba at the Bay of Pigs, Félix Rodríguez headed the hunt for Guevara in Bolivia. Upon hearing of Guevara's capture Rodríguez relayed the information to CIA headquarters at Langley, Virginia via CIA stations in various South American nations. After the execution, Rodríguez took Guevara's Rolex watch and several other personal items, often proudly showing them to reporters during the ensuing years.

A side issue connected with the guerrillas was the arrest and trial of Régis Debray. In April 1967 government forces captured Debray, a young French Marxist theoretician and writer who was a close friend of Fidel Castro, and accused him of collaborating with the guerrillas. Debray claimed that he had merely been acting as a reporter, and revealed that Che, who had mysteriously disappeared several years earlier, was leading the guerrillas. As Debray's trial — which had become an international cause célèbre — was beginning in early October, Bolivian authorities on October 11 reported (falsely) that Guevara had been shot and killed in an engagement with government forces on October 9.

On October 15 Castro acknowledged that the death had occurred and proclaimed three days of public mourning throughout Cuba. The death of Guevara was regarded as a severe blow to the socialist revolutionary movements throughout Latin America, and the rest of the third world countries.

In 1997, the skeletal remains of Guevara's handless body were exhumed from beneath an air strip near Vallegrande, positively identified by DNA matching, and returned to Cuba. On October 17, 1997 his remains were laid to rest with full military honours in a specially built mausoleum in the city of Santa Clara where he had won the said decisive battle, (actually Castro's own victory at Guisa probably was much more decisive) of the Cuban Revolution thirty-nine years before.

The Bolivian Diary

Also removed when Guevara was captured was his diary, which documented events of the guerrilla campaign in Bolivia. The first entry is on 7 November 1966 shortly after his arrival at the farm in Ñancahuazú, and the last entry is on 7 October 1967, the day before his capture. The diary tells how the guerrillas were forced to begin operations prematurely due to discovery by the Bolivian Army, explains Guevara's decision to divide the column into two units that were subsequently unable to re-establish contact, and describes their over-all failure. It records the rift between Guevara and the Bolivian Communist Party that resulted in Guevara having significantly fewer soldiers than originally anticipated. It shows that Guevara had a great deal of difficulty recruiting from the local populace, due in part to the fact that the guerrilla group had learned Quechua rather than the local language which was Tupí-Guaraní. As the campaign drew to an unexpected close, Guevara became increasingly ill. He suffered from ever-worsening bouts of asthma, and most of his last offensives were carried out in an attempt to obtain medicine.

The Bolivian Diary was quickly and crudely translated by Ramparts magazine and circulated around the world. Fidel Castro has denied involvement in this translation.

The intellectual and artistic

Guevara started playing chess by the age of 12. After the victory of the Cuban revolution, his fondness for chess was rekindled, and he attended most national and international tournaments held in Cuba.

During his adolescence he became passionate about poetry and he wrote poems throughout his life. His favorite poet was Chilean Pablo Neruda; a volume of Neruda's poetry was found in his knapsack after he was captured.

He was also an avid photographer and spent many hours photographing people and places. In later travels he enjoyed photographing archeological sites. The numerous photographs taken by and of him and other members of his guerrilla group that they left behind at their base camp after the initial clash with the Bolivian army in March 1967 provided the the Barrientos government with the first proof of his presence in Bolivia.

Hero cult

While pictures of Guevara's dead body were being circulated and the circumstances of his death debated, his legend began to spread. Demonstrations in protest against his execution occurred throughout the world, and articles, tributes, and poems were written about his life and death. Even liberal elements that had felt little sympathy with Guevara's communist ideals during his lifetime expressed admiration for his spirit of self-sacrifice. He is singled out from other revolutionaries by many young people in the West because he rejected a comfortable bourgeois background to fight for those who were deprived of political power and economic stability. And when he gained power in Cuba, he gave up all the trappings of high government office in order to return to the revolutionary battlefield and ultimately, to die.

Especially in the late 1960s, he became a popular icon symbolizing revolution and left-wing political ideals among youngsters in Western and Middle Eastern culture. A dramatic photograph of Guevara taken by photographer Alberto Korda in 1960 (see Che Guevara (photo)) soon became one of the century's most recognizable images, and the portrait was simplified and reproduced on a vast array of merchandise, such as T-shirts, posters, and baseball caps. Guevara's reputation even extended into theatre, where he is depicted as the narrator in Tim Rice and Andrew Lloyd Webber's musical Evita. This portrays Guevara as becoming disillusioned with Eva Perón and her husband, President Juan Domingo Perón, because of Perón's increasing corruption and tyranny. The narrator role involves creative license, because Guevara's only interaction with Eva Perón was to write her a letter in his youth, asking for a Jeep.

Guevara's remains, along with those of six of his fellow combatants during the guerrilla campaign in Bolivia, have rested since 1997 within a special mausoleum in the Plaza Comandante Ernesto Guevara in Santa Clara, Cuba. Some 205,832 persons visited the mausoleum in 2004, of whom 127,597 were foreigners. Among the tourists visiting the site were people from Argentina, Canada, Great Britain, Germany, Italy, Japan, South Africa, the United States, and Venezuela. Also inside the mausoleum is the original letter Guevara wrote to Castro in which he stated he would leave Cuba to continue to fight abroad for the cause of the revolution and renouncing all posts and his Cuban citizenship.

Called "the most complete human being of our age" by the French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre, Che's supporters believe he may yet prove to be the most important thinker and activist in Latin America since Simón Bolívar, leader of the South American independence movement and hero to subsequent generations of nationalists throughout Latin America.

Critique of hero cult

Those opposed to this hero cult point to what they see as the less savory aspects of Guevara's life, particularly his enthusiasm about executing opponents of the Cuban Revolution. This enthusiasm shows in his own writing, some of which is quoted in an article by one of his many detractors: The Killing Machine: Che Guevara, from Communist Firebrand to Capitalist Brand, July 11, 2005, Alvaro Vargas Llosa, The New Republic. For example, in his "Message to the Tricontinental" he writes of "hatred as an element of struggle; unbending hatred for the enemy, which pushes a human being beyond his natural limitations, making him into an effective, violent, selective, and cold-blooded killing machine."

Notes

- While June 14, 1928 is Guevara's official date of birth, it may not be the actual date of birth. The official story is that he was born eight months after his parents married; several sources suggest that he was born earlier (the date May 14 is the most prevalent), and that his mother was already pregnant at the time of her marriage.

- Re origin of the surname Guevara: "Basque: Castilianized form of Basque Gebara, a habitational name from a place in the Basque province of Araba. The origin and meaning of the place name are uncertain; it is recorded in the form Gebala by the geographer Ptolemy in the 2nd century ad. This is a rare name in Spain." Dictionary of American Family Names, Patrick Hanks, ed., London: 2003, Oxford University Press

- "Fuser" was a contraction of "El Furibundo Serna". See Anderson, Jon Lee. Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life, New York: 1997, Grove Press, p. 28

- "Quizás esa fue la primera vez que tuve planteado prácticamente ante mí el dilema de mi dedicación a la medicina o a mi deber de soldado revolucionario. Tenía delante de mí una mochila llena de medicamentos y una caja de balas, las dos eran mucho peso para transportarlas juntas; tomé la caja de balas, dejando la mochila ..." (English: "Perhaps this was the first time I was confronted with the real-life dilemma of having to choose between my devotion to medicine and my duty as a revolutionary soldier. Lying at my feet were a knapsack full of medicine and a box of ammunition. They were too heavy for me to carry both of them. I grabbed the box of ammunition, leaving the medicine behind ...".) First published in an article in Verde Olivo, La Habana, Cuba, February 26 1961. Subsequently published in the book, Guevara, Ernesto Che. Pasajes de la Guerra Revolucionaria, La Habana, Cuba: 1963, Ediciones Unión.

- Anderson, Jon Lee. Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life, New York: 1997, Grove Press, p. 372 and p. 425

- Buró de Represión de Actividades Comunistas (English: Bureau for the Repression of Communist Activities)

- October 7 1959

- November 26 1959

- February 23 1961

- Anderson, Jon Lee. Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life, New York: 1997, Grove Press, p. 545

- For complete text in Spanish, see Carta; for a generally accurate English translation, which, however, inexplicably omits the last paragraph of the letter, refer to Anderson, Jon Lee. Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life, New York: 1997, Grove Press, pp. 632-3.

- Profile of Laurent Kabila by BBC News

- Apuntes Filosóficos

- Notas Económicas

- English translation: National Liberation Army of Bolivia

- For example, on August 31 1967 Che wrote in his diary "Hay mensaje de Manila pero no se pudo copiar.", i.e. "There is a (coded radio) message from Manila ('Manila' being the code name for Havana) but we couldn't copy it." The content of this message has not been revealed, but it may have been of critical importance since by then Castro and the other Cubans who were directing the guerrillas' support network from Havana had to be aware of their dire straits.

- Castañeda, Jorge G. Che Guevara: Compañero, New York: 1998, Random House, pp. xiii - xiv; pp. 401-402. Guevara's amputated hands, preserved in formaldehyde, turned up in the possession of Fidel Castro a few months later. Castro reportedly wanted to put them on public display but was dissuaded from doing so by the vehement protests of members of Guevara's family.

- Granma article about Che's interest in Chess

- Najdorf vs. Guevara, Havana, 1962

- Alberto Korda

- On December 30 1998 the remains of ten more of the guerrillas who had fought alongside Guevara in Bolivia and whose secret burial sites there had been recently discovered by Cuban forensic investigators were also placed inside the "Che Guevara Mausoleum" in Santa Clara.

References

- Anderson, Jon Lee. Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life. New York: Grove Press. 1997. ISBN 0802116000.

- Fuentes, Norberto. La Autobiografia De Fidel Castro ("The Autobiography of Fidel Castro"). Mexico D.F: Editorial Planeta. 2004. ISBN 8423336042, ISBN: 9707490012

- Guevara, Ernesto "Che" (and Waters, Mary Alice editor) Episodes of the Cuban Revolutionary War 1956-1958. New York: Pathfinder. 1996. ISBN 0873488245. (See reference to "El Viscaíno" on page 186).

- Matos, Huber. Como llegó la Noche ("How night arrived"). Barcelona: Tusquet Editores, SA. 2002. ISBN 8483109441.

- Morán Arce, Lucas. La revolución cubana, 1953-1959: Una versión rebelde ("The Cuban Revolution, 1953-1959: a rebel version"). Ponce, Puerto Rico: Imprenta Universitaria, Universidad Católica. 1980. ISBN B0000EDAW9.

- Rojo del Río, Manuel. La Historia Cambió En La Sierra ("History changed in the Sierra"). 2a Ed. Aumentada (Augmented second edition). San José, Costa Rica: Editorial Texto. 1981.

External links

Documentary sites

Works by Guevara, photos of Guevara, etc.

- The Che Guevara internet archive – contains written works, pictures, and speeches

- ElCheVive.com contains more than 200 pictures and other information in three languages (English, Spanish and Dutch)

- El-Comandante.com – including biography, photographs, and texts of Che Guevara

- The Death of Che Guevara: Declassified, from the National Security Archive

- Bolivia on the Day of the Death of Che Guevara, by Richard Gott with photos by Brain Moser (Published in Le Monde diplomatique, August 11, 2005)

- Che Guevara – Biography, pictures, and texts of Che Guevara

- A 4-minute excerpt of Che speaking to the UN on December 11, 1964, in RealPlayer formatClick to listen

- A brief excerpt of Che speaking to the UN on December 11, 1964 in .wav formatClick to listen

- Guerrillero heroico - contains information, articles, pictures, some ebooks about Che Guevara in English, Spanish and Russian

Forums

- Che-Lives, a site dedicated to Che Guevara, including a revolutionary leftist discussion area.

- Another discussion area is The Rebel Alliance Leftist Community.

Photographs

Writings by Che Guevara

- Self-Portrait: Che Guevara, Ocean Press, 320pp, paperback, 2005

- The Diary of Che Guevara, Amereon Ltd,

- The Motorcycle Diaries: Notes on a Latin American Journey, Perennial Press, ISBN 0007182228.

- Back on the Road: A Journey to Central America (Harvill Panther S.), The Harvill Press, paperback, ISBN 0802139426.

- The African Dream: The Diaries of the Revolutionary War in the Congo, Grove Press, paperback.

- Bolivian Diary, Pimlico, paperback, ISBN 0712664572

- Guerrilla Warfare, Souvenir Press Ltd, paperback, ISBN 0285636804.

- Reminiscences of the Cuban Revolutionary War, Monthly Review Press, paperback, 1998

- Che Guevara Speaks, Pathfinder, paperback

- Che Guevara Talks to Young People, Pathfinder, paperback

- Che Guevara Reader: Writings on Guerrilla Warfare, Politics and History, Ocean Press, paperback

- Critical Notes on Political Economy, Ocean Press, paperback

- Our America and Theirs, Ocean Press (AU), paperback, ISBN 1876175818.

- Manifesto: Three Classic Essays on How to Change the World, Consortium, paperback

- Socialism and Man in Cuba: Also Fidel Castro on the Twentieth Anniversary of Guevara's Death, Monad, paperback

- Pasajes de la Guerra Revolucionaria: Congo – Guevara's complete Congo Diary in Spanish, in PDF format

- Pensamiento y acción – A selection of Guevara's writings in Spanish, including El socialismo y el hombre nuevo, in PDF format

- Obras Escogidas – Che's selected works in Spanish, including his most important speeches, in PDF format

Writings about Che Guevara

General

Other

|

Criticism, praise, etc.

|

Trivia

In the movies

Movies and actors who have portrayed Che Guevara:

- El 'Che' Guevara at IMDb – Francisco Rabal (1968)

- Che! at IMDb – Omar Sharif (1969)

- Evita – Antonio Banderas (1996)

- "El Día Que Me Quieras" at IMDb ("The Day You'll Love Me" is a song by Carlos Gardel) – dir. Leandro Katz (1997)

- Hasta la victoria siempre at IMDb – Alfredo Vasco (1999)

- Fidel at IMDb – Gael García Bernal (2002)

- The Motorcycle Diaries (Diarios de motocicleta) – Gael García Bernal (2004)

- Che: The Movie at IMDb – Benicio Del Toro (announced to begin production in 2005)

In video games

- Che Guevara's exploits during the Cuban Revolution were very loosely dramatized in the 1987 video game Guevara, released by SNK in Japan and "converted" into Guerrilla War for Western audiences, removing all references to Che but keeping all the visuals and a game map that clearly resembles Cuba. Original copies of the "Guevara" edition of the Japanese Famicom edition go for high amounts on the collectors' market.

- In Tom Clancy's Splinter Cell: Pandora Tomorrow, a figure leading a Indonesian rebel force know as Darah Dan Doa named Suhadi Sadono bears a striking resemblence to Guevara. During a between mission cut scene in the form of a news report, a girl in Paris is seen wearing a t-shirt with a image of Sadono printed on it. This is most likely an allusion to the famous image of Guevara printed on t-shirts.

See also

- History of Cuba

- Luis Carlos Prestes

- Pop culture images of Che Guevara

- Guevarism

- Che-Lives

- Colegio Cesar Chavez