This is an old revision of this page, as edited by One Night In Hackney (talk | contribs) at 12:48, 21 December 2009 (→Early life: Doesn't belong in early life section). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

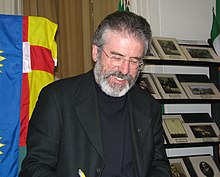

Revision as of 12:48, 21 December 2009 by One Night In Hackney (talk | contribs) (→Early life: Doesn't belong in early life section)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) For other people named Gerry Adams, see Gerry Adams (disambiguation).| Gerry Adams Gearóid Mac Ádhaimh MLA, MP | |

|---|---|

| |

| President of Sinn Féin | |

| Incumbent | |

| Assumed office 1983 | |

| Preceded by | Ruairí Ó Brádaigh |

| Member of the Northern Ireland Assembly for Belfast West | |

| Incumbent | |

| Assumed office 25 June 1998 | |

| Preceded by | new assembly |

| Member of Parliament for Belfast West | |

| Incumbent | |

| Assumed office 1 May 1997 | |

| Preceded by | Joe Hendron |

| Majority | 19,315 (55.9%) |

| In office 9 June 1983 – 9 April 1992 | |

| Preceded by | Gerry Fitt |

| Succeeded by | Joe Hendron |

| Personal details | |

| Born | (1948-10-06) 6 October 1948 (age 76) Belfast, County Antrim, Northern Ireland |

| Nationality | Irish |

| Political party | Sinn Féin |

| Spouse | Collette McArdle |

| Website | Sinn Féin - Gerry Adams |

Gerard "Gerry" Adams, MLA, MP (Template:Lang-ga; born 6 October 1948) is an Irish Republican politician and abstentionist Westminster Member of Parliament for Belfast West. He is the president of Sinn Féin, which is the largest political party in Northern Ireland and fourth largest party in the Republic of Ireland.

From the late 1980s, Adams was an important figure in the Northern Ireland peace process, initially following contact by the then Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) leader John Hume and subsequently with the Irish and British governments and then other parties. In 2005, the IRA indicated that its armed campaign was over and that it is now exclusively committed to democratic politics. Under Adams, Sinn Féin changed its traditional policy of abstentionism towards Oireachtas Éireann, the parliament of the Republic of Ireland, in 1986 and later took seats in the power-sharing Northern Ireland Assembly. However, Sinn Féin retains a policy of abstentionism towards the Westminster Parliament although since 2002 receives allowances for staff and takes up offices in the House of Commons.

Early life

Adams was born in West Belfast into a nationalist Catholic family consisting of 10 children who survived infancy (five boys, five girls) and their parents, Gerry Adams Sr. and Annie Hannaway.

Gerry Sr. and Annie came from strong republican backgrounds. Adams' grandfather, also called Gerry Adams, had been a member of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) during the Irish War of Independence. Two of Adams' uncles, Dominic and Patrick Adams, had been interned by the governments in Belfast and Dublin. Although it is reported that his uncle Dominic was a one-time IRA chief of staff, J. Bowyer Bell, in his widely respected book, The Secret Army: The IRA 1916 (Irish Academy Press), states that Dominic Adams was a senior figure in the IRA of the mid-1940s. Gerry Sr. joined the IRA aged sixteen; in 1942 he participated in an IRA ambush on a Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) patrol but was himself shot, arrested and sentenced to eight years imprisonment.

Adams' maternal great-grandfather, Michael Hannaway, was a member of the Fenians during their dynamiting campaign in England in the 1860s and 1870s. Michael's son, Billy, was election agent for Éamon de Valera in 1918 in West Belfast but refused to follow de Valera into democratic and constitutional politics upon the formation of Fianna Fáil. Annie Hannaway was a member of Cumann na mBan, the women's branch of the IRA. Three of her brothers (Alfie, Liam and Tommy) were known IRA members.

Adams attended St Finian's Primary School on the Falls Road where he was taught by De La Salle brothers. He then attended St Mary's Christian Brothers Grammar School after passing the eleven-plus exam in 1960. He left St. Mary's with six O-levels, and became a bartender, but became increasingly involved in the Irish republican movement, joining Sinn Féin and Fianna Éireann in 1964, after being radicalised by the Divis Street riots during the general election campaign.

When Third Way Magazine asked Adams whether he was a Christian he said: 'I like the sense of there being a God, and I do take succour now from the collective comfort of being at a Mass or another religious event where you can be anonymous and individual – just a sense of community at prayer and of paying attention to that spiritual dimension which is in all of us; and I also take some succour in a private, solitary way from being able to reflect on those things.'

Early political career

In the late 1960s, a civil rights campaign developed in Northern Ireland. Adams was an active supporter and joined the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association in 1967. However, the civil rights movement was met with protests from loyalist counter-demonstrators. This culminated in August 1969, when Northern Ireland cities like Belfast and Derry erupted in major rioting and British troops were called in at the request of the Government of Northern Ireland (see 1969 Northern Ireland Riots).

Adams was active in Sinn Féin at this time. In August 1971, internment was reintroduced to Northern Ireland under the Special Powers Act 1922. Adams was interned in March 1972, on HMS Maidstone, but was released in June to take part in secret, but abortive talks in London. The IRA negotiated a short-lived truce with the British and an IRA delegation met with the British Home Secretary, William Whitelaw at Cheyne Walk in Chelsea. The delegation included Sean Mac Stiofain (Chief of Staff), Daithi O'Conaill, Seamus Twomey, Ivor Bell, Martin McGuinness and Gerry Adams {{citation}}: Empty citation (help), and Myles Shevlin, a Dublin solicitor. The IRA insisted Adams be included in the meeting and he was released from internment to participate. Following the failure of the talks, he played a central role in planning the bomb blitz on Belfast known as Bloody Friday. He was re-arrested in July 1973 and interned at Long Kesh internment camp. After taking part in an IRA-organised escape attempt he was sentenced to a period of imprisonment.

During the Hunger Strikes of 1981, Adams played an important policy-making role, which saw the emergence of his party as a political force. In 1983 he was elected president of Sinn Féin and became the first Sinn Féin MP elected to the British House of Commons since Phil Clarke and Tom Mitchell in the mid-1950s. Following his election as MP for Belfast West the British government lifted a ban on him travelling to Great Britain. In line with Sinn Féin policy, he refused to take his seat in the House of Commons.

On 14 March 1984, Adams was seriously wounded in an assassination attempt when several Ulster Freedom Fighters (UFF) gunmen fired about twenty shots into the car in which he was travelling. After the shooting, under-cover plain clothes police officers seized three suspects who were later convicted and sentenced. One of the three was John Gregg. Adams claimed that the British army had prior knowledge of the attack and allowed it to go ahead.

Allegations of IRA membership

Adams has stated repeatedly that he has never been a member of the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA). However journalists such as Ed Moloney, Peter Taylor, Mark Urban and historian Richard English have all named Adams as part of the IRA leadership since the 1970s. Adams has denied Moloney's claims, calling them "libellous".

President of Sinn Féin

In 1978, Gerry Adams became joint-vice-president of Sinn Féin and he became a key figure in directing a challenge to the Sinn Féin leadership of President Ruairí Ó Brádaigh and joint-Vice President Dáithí Ó Conaill.

The 1975 IRA-British truce is often viewed as the event that began the challenge to the original Provisional Sinn Féin leadership, which was said to be Southern-based and dominated by southerners like Ó Brádaigh and Ó Conaill. However, the Chief of Staff of the IRA at the time, Seamus Twomey, was a senior figure from Belfast. Others in the leadership were also Northern based, including Billy McKee from Belfast. Adams (allegedly) rose to become the most senior figure in the IRA Northern Command on the basis of his absolute rejection of anything but military action, but this conflicts with the fact that during his time in prison Adams came to reassess his approach and became more political. It is alleged that "provisional" republicanism was founded on its opposition to the communist-inspired "broad front" politics of the Cathal Goulding-led Official IRA, but this too is disputed.

One of the core reasons that the Provisional IRA and provisional Sinn Féin were founded, in December 1969 and January 1970, respectively, was that people like Ó Brádaigh and O'Connell, and Billy McKee, opposed participation in constitutional politics, the other was the failure of the Goulding leadership to provide for the defence of nationalist areas. When, at the December 1969 IRA convention and the January 1970 Sinn Féin Ard Fheis the delegates voted to participate in the Dublin (Leinster House), Belfast (Stormont) and London (Westminster) parliaments, the organizations split. Gerry Adams, who had joined the Republican Movement in the early 1960s, did not go with the Provisionals until later in 1970.

In Long Kesh in the mid-1970s, and writing under the pseudonym Brownie in Republican News, Adams called for increased political activity, especially at a local level, by Republicans. The call resonated with younger Northern people, many of whom had been active in the Provisional IRA but had not necessarily been highly active in Sinn Féin. In 1977, Adams and Danny Morrison drafted the address of Jimmy Drumm at the Annual Wolfe Tone Commemoration at Bodenstown. The Address was viewed as watershed in that Drumm acknowledged that the war would be a long one and that success depended on political activity that would complement the IRA's armed campaign. For some, this wedding of politics and armed struggle culminated in Danny Morrison's statement at the 1981 Sinn Féin Ard Fheis in which he asked "Who here really believes we can win the war through the Ballot box? But will anyone here object if, with a ballot paper in one hand and the Armalite in the other, we take power in Ireland". For others, however, the call to link political activity with armed struggle had been clearly defined in Sinn Féin policy and in the Presidential Addresses of Ruairí Ó Brádaigh, but it had not resonated with the young Northerners.

Ironically, while Adams was advocating that the Republican Movement needed more involvement in politics, he was one of the key opponents of Sinn Féin putting forward a candidate for the first election to the European Parliament, in 1979. Even after the election of Bobby Sands as MP for Fermanagh/South Tyrone, a part of the mass mobilization associated with the 1981 Irish Hunger Strike by republican prisoners in the H blocks of the Maze prison (known as Long Kesh by Republicans), Adams was cautious about political involvement by Sinn Féin. Charles Haughey, the Taoiseach of the Republic of Ireland, called an election for June 1981. At an Ard Chomhairle meeting Adams recommended that they contest only four constituencies. Instead, H-Block/Armagh Candidates contested nine constituencies and elected two TDs. This, along with the election of Bobby Sands, was precursor to a big electoral breakthrough in elections in 1982 to the Northern Ireland Assembly. Adams, Danny Morrison, Martin McGuinness, Jim McAllister, and Owen Carron were elected as abstentionists. The SDLP had announced before the election that it would not take any seats and so its 14 elected representatives also abstained from participating in the Assembly and it was a failure. The 1982 election was followed by the 1983 Westminster election, in which Sinn Féin's vote increased and Gerry Adams was elected, as an abstentionist, as MP for West Belfast. It was in 1983 that Ruairí Ó Brádaigh resigned as President of Sinn Féin and was succeeded by Gerry Adams.

Republicans had long claimed that the only legitimate Irish state was the Irish Republic declared in the Proclamation of the Republic of 1916, which they considered to be still in existence. In their view, the legitimate government was the IRA Army Council, which had been vested with the authority of that Republic in 1938 (prior to the Second World War) by the last remaining anti-Treaty deputies of the Second Dáil. Adams continued to adhere to this claim of republican political legitimacy until quite recently - however in his 2005 speech to the Sinn Féin Ard Fheis he explicitly rejected it.

As a result of this non-recognition, Sinn Féin had abstained from taking any of the seats they won in the British or Irish parliaments. At its 1986 Ard Fheis, Sinn Féin delegates passed a resolution to amend the rules and constitution that would allow its members to sit in the Dublin parliament (Leinster House/Dáil Éireann). At this Ruairí Ó Brádaigh led a small walkout, just as he and Sean Mac Stiofain had done sixteen years earlier with the creation of Provisional Sinn Féin. This minority, which rejected dropping the policy of abstentionism, now nominally distinguishes itself from Provisional Sinn Féin by using the name Republican Sinn Féin (or Sinn Féin Poblachtach), and maintains that they are the true Sinn Féin republicans.

Adams' leadership of Sinn Féin was supported by a Northern-based cadre that included people like Danny Morrison and Martin McGuinness. Adams and others, over time, pointed to Republican electoral successes in the early and mid-1980s, when hunger strikers Bobby Sands and Kieran Doherty were elected to the British House of Commons and Dáil Éireann respectively, and they advocated that Sinn Féin become increasingly political and base its influence on electoral politics rather than paramilitarism. The electoral effects of this strategy were shown later by the election of Adams and McGuinness to the House of Commons.

Voice ban

Adams's prominence as an Irish Republican leader was increased by the ban on the media broadcast of his voice (the ban actually covered eleven republican and loyalist organisations, but in practice Adams was the only one prominent enough to appear regularly on TV). This ban was imposed by the then prime minister Margaret Thatcher on 19 October 1988, the reason given being to "starve the terrorist and the hijacker of the oxygen of publicity on which they depend" after the BBC interviewed Martin McGuinness and Adams had been the focus of a row over an (unmade) edition of the Channel 4 discussion programme After Dark.

A similar ban, known as Section 31, had been law in the Republic of Ireland since the 1970s. However media outlets soon found ways around the ban, initially by the use of subtitles, but later and more commonly by the use of an actor reading his words over the images of him speaking. One actor who voiced Adams was Paul Loughran.

This ban was lampooned in cartoons and satirical TV shows, such as Spitting Image, and in The Day Today and was criticised by freedom of speech organisations and British media personalities, including BBC Director General John Birt and BBC foreign editor John Simpson. The ban was lifted by British Prime Minister John Major on 17 September 1994.

Moving into mainstream politics

Sinn Féin continued its policy of refusing to sit in the Westminster Parliament even after Adams won the Belfast West constituency. He lost his seat to Joe Hendron of the Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) in the 1992 general election. However, he easily regained it at the next election in May 1997.

Under Adams, Sinn Féin appeared to move away from being a political voice of the Provisional IRA to becoming a professionally organised political party in both Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland.

SDLP leader John Hume, MP, identified the possibility that a negotiated settlement might be possible and began secret talks with Adams in 1988. These discussions led to unofficial contacts with the British Northern Ireland Office under the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, Peter Brooke, and with the government of the Republic under Charles Haughey – although both governments maintained in public that they would not negotiate with "terrorists".

These talks provided the groundwork for what was later to be the Belfast Agreement, as well as the milestone Downing Street Declaration and the Joint Framework Document.

These negotiations led to the IRA ceasefire in August 1994. Irish Taoiseach Albert Reynolds, who had replaced Haughey and who had played a key role in the Hume/Adams dialogue through his Special Advisor Martin Mansergh, regarded the ceasefire as permanent. However the slow pace of developments, contributed in part to the (wider) political difficulties of the British government of John Major and consequent reliance on Ulster Unionist Party votes in the House of Commons, led the IRA to end its ceasefire and resume the campaign.

A restituted ceasefire later followed, as part of the negotiations strategy, which saw teams from the British and Irish governments, the Ulster Unionist Party, the SDLP, Sinn Féin and representatives of loyalist paramilitary organizations, under the chairmanship of former United States Senator George Mitchell, produced the Belfast Agreement (also called the Good Friday Agreement as it was signed on Good Friday, 1998). Under the agreement, structures were created reflecting the Irish and British identities of the people of Ireland, with a British-Irish Council and a Northern Ireland Legislative Assembly created.

Articles 2 and 3 of the Republic's constitution, Bunreacht na hÉireann, which claimed sovereignty over all of Ireland, were reworded, and a power-sharing Executive Committee was provided for. As part of their deal Sinn Féin agreed to abandon its abstentionist policy regarding a "six-county parliament", as a result taking seats in the new Stormont-based Assembly and running the education and health and social services ministries in the power-sharing government.

Opponents in Republican Sinn Féin accused Sinn Féin of "selling out" by agreeing to participate in what it called "partitionist assemblies" in the Republic and Northern Ireland. However Gerry Adams insisted that the Belfast Agreement provided a mechanism to deliver a united Ireland by non-violent and constitutional means, much as Michael Collins had said of the Anglo-Irish Treaty nearly 80 years earlier.

When Sinn Féin came to nominate its two ministers to the Northern Ireland Executive, the party, like the SDLP and the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) chose for tactical reasons not to include its leader among its ministers. (When later the SDLP chose a new leader, it selected one of its ministers, Mark Durkan, who then opted to remain in the Committee.)

Adams remains the President of Sinn Féin, with Caoimhghín Ó Caoláin serving as Sinn Féin parliamentary leader in Dáil Éireann, and Daithí McKay is head of the Sinn Féin group in the Northern Ireland Assembly.

Adams was re-elected to the Northern Ireland Assembly on 8 March 2007, and on 26 March 2007 he met with DUP leader Ian Paisley face-to-face for the first time, and the two came to an agreement regarding the return of the power-sharing executive in Northern Ireland.

In January 2009 Adams attended the United States presidential Inauguration of Barack Obama in 2009 as a guest of US Congressman Richard Neal. On April 9, 2009 Adams visited Israel and the Gaza Strip and met with Ismail Haniyeh, a senior political leader of Hamas.

See also

- IRA Army Council

- Provisional Irish Republican Army

- Sinn Féin

- History of Northern Ireland

- The Troubles

- Northern Ireland peace process

- J. Bowyer Bell. The Secret Army: The IRA 1916 -. Dublin: Irish Academic Press, 1979.

- Colm Keena. A Biography of Gerry Adams. Cork, Ireland: Mercier Press, 1990.

- Robert W. White. Ruairi O Bradaigh, the Life and Politics of an Irish Revolutionary. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2006.

- Anthony McIntyre. Gerry Adams Man Of War and Man Of Peace?, academic lecture examining Gerry Adams' role in the Republican Movement

References

- "World Politics Review | Sinn Fein's Adams on 'Peace Mission' to Middle East". Worldpoliticsreview.com. Retrieved 2008-10-31.

- "Newshound: Daily Northern Ireland news catalog - Irish News article". Nuzhound.com. Retrieved 2008-10-31.

- Cairt Chearta do Chách Sinn Féin press release, 26 January 2004.

- http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/northern_ireland/8089501.stm

- http://www.sinnfein.ie/contents/16580

- Who hit and who missed Euro target?

- "Full text: IRA statement". The Guardian. 28 July 2005. Retrieved 2007-03-17.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - http://www.parliament.uk/commons/lib/research/briefings/snpc-01667.pdf

- ^ Lalor, Brian (ed) (2003). The Encyclopaedia of Ireland. Dublin, Ireland: Gill & Macmillan. pp. 7–8. ISBN 0-7171-3000-2.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - Thirdway - Talking of Peace - Interview with Gerry Adams (via Wayback Machine)

- "1984: Sinn Féin leader shot in street attack". BBC. Retrieved 2007-03-22.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - Kevin Maguire (14 December 2006). "Adams wants 1984 shooting probe". BBC. Retrieved 2007-03-22.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - Rosie Cowan (1 October 2002). "Adams denies IRA links as book calls him a genius". The Guardian. Retrieved 2007-03-22.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - Moloney, Ed (2002). A Secret History of the IRA. Penguin Books. p. 140. ISBN 0-141-01041-X.

- Taylor, Peter (1997). Provos The IRA & Sinn Féin. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 140. ISBN 0-7475-3818-2.

- English, Richard (2003). Armed Struggle: The History of the IRA. Pan Books. p. 110. ISBN 0-330-49388-4.

- Urban, Mark (1993). Big Boys' Rules: SAS and the Secret Struggle Against the IRA. Faber and Faber. p. 26. ISBN 0-571-16809-4.

- Adams denies IRA book allegations. BBC News. 12 September 2002

- Sinn Féin: where does the money come from?, Irish Independent, 19 June 2004

- Robert White, Ruairí Ó Brádaigh, The Life and Politics of an Irish Revolutionary, pp. 258-59.

- Taylor, p. 291.

- Anderson, Brendan (2002). Joe Cahill: A Life in the IRA. O'Brien Press. p. 340. ISBN 0-86278-836-6.

- O'Brien, Brendan (1999). The Long War: The IRA and Sinn Féin. O'Brien Press. p. 130. ISBN 0-86278-606-1.

- Bishop, Patrick & Mallie, Eamonn (1987). The Provisional IRA. Corgi Books. p. 448. ISBN 0-552-13337-X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - The 'broadcast ban' on Sinn Fein, BBC News Online, 5 April 2005

- Edgerton, Gary Quelling the "Oxygen of Publicity": British Broadcasting and "The Troubles" During the Thatcher Years, The Journal of Popular Culture, Volume 30, Issue 1, pp. 115-32

- Dubbing SF voices becomes the stuff of history, By Michael Foley The Irish Times, 17 September 1994

- Misplaced Pages article on After Dark and Gerry Adams, accessed 7th August 2009

- "www.ulsteractors.com". ulsteractors.com. Retrieved 2009-04-10.

- Sinn Fein's Gerry Adams Wins In Northern Ireland. Associated Press, 8 March 2007.

- "May date for return to devolution". BBC. 26 March 2007. Retrieved 2007-03-26.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - 19/Jan/2009 Barack Obama inauguration: Gerry Adams to attend ceremony Telegraph.co.uk

- 10/Apr/2009 Irish leader Gerry Adams meets Hamas-led government in Gaza .imemc.org

Published works

- Falls Memories, 1982

- The Politics of Irish Freedom, 1986

- A Pathway to Peace, 1988

- An Irish Voice

- Cage Eleven, 1990

- The Street and Other Stories, 1992

- Free Ireland: Towards a Lasting Peace, 1995

- Before the Dawn, 1996, Brandon Books, ISBN 0-434-00341-7

- Selected Writings

- Who Fears to Speak...?, 2001(Original Edition 1991), Beyond the Pale Publications, ISBN 1-90096-013-3

- An Irish Journal, 2001, Brandon Books, ISBN 0-86322-282-X

- Hope and History, 2003, Brandon Books, ISBN 0-86322-330-3

- A Farther Shore, 2005, Random House

- An Irish Eye, 2007, Brandon Books

External links

- Sinn Féin - Gerry Adams official profile

- Guardian Politics Ask Aristotle - Gerry Adams

- TheyWorkForYou.com - Gerry Adams MP

- The Public Whip - Gerry Adams voting record

- Leargas Gerry Adams' personal blog

- Interview with Gerry Adams February 2006

| Parliament of the United Kingdom | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded byGerry Fitt | Member of Parliament for Belfast West 1983–1992 |

Succeeded byJoe Hendron |

| Northern Ireland Assembly | ||

| Preceded byNew creation | MLA for Belfast West 1998 - |

Succeeded byIncumbent |

| Party political offices | ||

| Preceded byJoe Cahill and Dáithí Ó Conaill |

Vice-President of Sinn Féin with Joe Cahill then Dáithí Ó Conaill 1978–1983 |

Succeeded byPhil Flynn |

| Members of Parliament from Northern Ireland | |

|---|---|

| Alliance Party of Northern Ireland | |

| Democratic Unionist Party | |

| Sinn Féin (abstentionist) | |

| Social Democratic and Labour Party | |

| Traditional Unionist Voice | |

| Ulster Unionist Party | |

| Independent | |

| Party leaders in Northern Ireland | |

|---|---|

- Leaders of Sinn Féin

- Members of the United Kingdom Parliament for Northern Irish constituencies

- Members of the United Kingdom Parliament for Belfast constituencies

- Sinn Fein MPs (UK)

- Northern Ireland MPAs 1982-1986

- Members of the Northern Ireland Forum

- Northern Ireland MLAs 1998-2003

- Northern Ireland MLAs 2003-2007

- Northern Ireland MLAs 2007-

- UK MPs 1983-1987

- UK MPs 1987-1992

- UK MPs 1997-2001

- UK MPs 2001-2005

- UK MPs 2005-

- People from Belfast

- 1948 births

- Living people

- Republicans imprisoned during the Northern Ireland conflict

- Irish republicans interned without trial

- Shooting survivors